Abstract

The personal characteristics of the members, the organizational relationships, and the internal procedures need to be managed. Knowledge needs to be acquired, assimilated, transformed, and applied to create organizational value. Then, the relationship between intellectual capital and the absorptive capacity are fundamental. Family businesses, those governed and/or managed by members of the same family throughout the generations, represent more than half of the existing organizations, reaching figures close to 90% in some locations. There is a gap in the research about intellectual capital and the absorptive capacity of a family business; thus it must be explored deeply. The objective of this essay is to relate the previous evidence about the intellectual capital and the absorptive capacity of family businesses for innovative performance, identify previous results and the gap in the literature, present a conceptual model, and propose an agenda for future research. This essay was developed through a literature review. Then, this study contributes to original insights on the role of intellectual capital and absorption capacity in the innovative performance of family businesses.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The intangible assets of organizations are enhanced due to their potential to create value and competitive advantages (Wexler 2002; Grant 1996). These intangible assets such as knowledge, experiences, routines, and relationships are capable of creating value and represent the organizational intellectual capital (Núñez Ramírez et al. 2017; Wexler 2002; Zahra and George 2002; Cohen and Levinthal 1990).

All knowledge generated through the organizational intellectual capital, namely, the personal characteristics of the members, the organizational relationships, and the internal procedures, need to be managed to create value (Wang and Noe 2010; Argote and Ingram 2000; Grant 1996; Nonaka 1994). The absorptive capacity of the organization is part of this management, its set of routines and processes through which the organization acquires, assimilates, transforms, and applies the knowledge with the purpose of value creation (Zahra and George 2002).

In the context of constant changes, for the organization to remain competitive and prolong its survival, it must have a significant innovative performance (Serrano-Bedia et al. 2016). In other words, the organization must create novelties that add value (Tidd and Bessant 2014). While the absorptive capacity is a condition for the innovative process (Zahra and George 2002), intellectual capital positively influences the innovative performance of organizations (Prod and Carlos 2015).

The focus of this essay is on the gaps in the relationship between intellectual capital and the absorptive capacity of family businesses for innovative performance. Family businesses, those governed and/or managed by members of the same family throughout the generations (Chua et al. 1999), represent more than half of the existing organizations, reaching figures close to 90% depending on the location (Chua et al. 1999; Daspit et al. 2017).

Despite these data, studies with empirical research do not agree on the innovative performance of these organizations (Broekaert et al. 2016; Stenholm et al. 2016; De Massis et al. 2016; Miller et al. 2015). The researches that relate the intellectual capital, the absorptive capacity of family businesses for innovation, are sparse (Ferreira and Ferreira 2017). Therefore, due to the existence of a gap, there is a need to research this issue. Thus, the objective of this essay is to relate the previous evidence about the intellectual capital and the absorptive capacity of family businesses for innovative performance, identify the gap in the literature, and propose agendas for future research.

The essay is organized as follows. It begins with a review of the literature on intellectual capital, its dimensions; followed by the absorptive capacity, its phases; and the presentation of studies on the innovative performance of family businesses. After it is shown the previous evidence and some of the investigation gap observed, an item also composed by a table synthesizes the result of the previous studies. Lastly, in the final considerations, the contributions and limitations are identified, and proposals for future studies related to the identified gap are presented.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Organizational Intellectual Capital

Intellectual capital, a product of the knowledge era (Núñez Ramírez et al. 2017), represents the collective knowledge of the organization (Ngah et al. 2016); it has three dimensions associated with each other: human capital, structural capital, and relational or social capital (Wexler 2002; Zahra and George 2002; Cohen and Levinthal 1990).

Human capital represents the value of the personal characteristics of the members of the organization, such as knowledge, talent, values, creativity, leadership, ability to learn, flexibility, loyalty, proactivity, ability to solve problems, and attitudes. This capital is lost with the exit of the member (Ngah et al. 2016; Wexler 2002; Zahra and George 2002; Cohen and Levinthal 1990). However, such personal characteristics must be separated from the intellectual property belonging to the company and must be protected by contract (Núñez Ramírez et al. 2017). Concerning the human capital of family businesses, which are in a highly changing environment and wish to remain innovative, they must receive long-term investments, whether or not they are family members, to develop a cohesive corporate culture (Miller et al. 2015).

Structural capital, on the other hand, represents the non-human knowledge that remains in the organization even if the members leave it, which refers to the databases, corporate culture, systems, technologies, routines, procedure manuals, and strategies that generate value for the organization. Structural capital is a property of the organization (Núñez Ramírez et al. 2017; Ngah et al. 2016; Wexler 2002; Zahra and George 2002; Cohen and Levinthal 1990).

Relational capital is the most relevant source of competitive advantage (Saleh and Masduki 2016), also called social capital, which is the set of organizational relationships that affect integration, commitment, cooperation, cohesion, connection, and social responsibility (Núñez Ramírez et al. 2017). The organization alone does not get all the resources needed to prosper. So there should be cooperation and forming alliances (Yoo et al. 2016). In family businesses, long-term relationships should be fostered so that innovation is maintained continuously, without disruptions (Miller et al. 2015).

This nature of intellectual capital can also be understood as the actual or potential resources inherent to more or less institutionalized relations of mutual recognition (Bourdieu apud Maak 2007). This capital refers exactly to these internal or external organizational relationships (Wexler 2002), focusing on interactions between partners, such as other organizations, customers, suppliers, public administration, and society in general. Partners are considered as key elements for innovation (Vlaisavljevic et al. 2016) and organizational performance (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998). In other words, relational capital significantly influences the capacity for innovation and organizational performance (Sulistyo and Siyamtinah 2016). Therefore, organizations should coordinate the different perspectives of intellectual capital to improve their performance and competitive advantage (Lu et al. 2010).

The ability of the organization to cooperate is associated with relational capital; these interactions between partners depend on mutual trust, exchange of information, and mutual commitment (Garcıa and Bounfour 2014 apud Yoo et al. 2016). Thus, relational capital acts as a bridge facilitating the knowledge sharing between the partners (Kale and Singh 2007 apud Yoo et al. 2016). For instance, the intention to learn is a relevant antecedent for organizational learning to occur in alliances; in this case, there is a positive influence of absorptive capacity and relational capital for the learning to be carried out (Yoo et al. 2016).

In order for an organization to manage its knowledge and create value, it is necessary to integrate the dimensions of intellectual capital, that is, human capital allows the transfer of knowledge through structural capital, which is reflected in the relations of the organization (relational capital) (Fierro et al. apud Núñez Ramírez et al. 2017).

The organization should be able to store knowledge even if members leave it (Núñez Ramírez et al. 2017; Wexler 2002). For this reason, organizational memory should be built since valuable information is found in inter- and intra-organizational relationships (Wexler 2002). This demand is directly connected to the absorptive capacity of the organization (Yoo et al. 2016). In the next subtopic, a review of the literature on absorptive capacity and its implications on innovative performance are briefly presented.

2.2 Absorptive Capacity and Innovation Performance

In the 1990s, Cohen and Levinthal (1990) presented the ability of the organization to recognize, assimilate, and apply external information as a critical factor for innovation capacity. In the following decade, Zahra and George (2002) presented a review and reconceptualization of the absorptive capacity as a dynamic capacity when analyzing its multidimensional nature, separated it into two phases, potential (acquisition and assimilation) and performed (transformation and exploitation). In the potential phase, the first two steps take place to achieve the realization, meaning, the final moments in which the absorptive capacity ceases to be potential, becomes realized, and influences the organizational performance (Zahra and George 2002).

The acquisition, the first step to the absorption of knowledge, is the ability of the organization to identify and acquire knowledge and is the initial inference with the primary knowledge. The second step, the assimilation, the understanding of knowledge, occurs through routines and processes that allow the analysis, classification, and interpretation of knowledge acquired. Once the knowledge is understood, internalized, the next step is to transform it into a new knowledge useful to the organization. Finally, the last step for the absorption of knowledge, exploitation, is the ability of the organization to implement, use, this new knowledge in its operations, whether innovating in processes, products, or in organizational management itself (Zahra and George 2002; Andersén 2015).

Applying knowledge to tangible organizational operations is complex and time-consuming (Andersén 2015; Nonaka 1994). The exploitation of knowledge depends on the kind of knowledge that will be absorbed (Ipe 2003; Grant 1996) and is positively related to the stability of the organization (Andersén 2015) and the subsequent change in its performance (Argote and Ingram 2000). On the other hand, access to external knowledge that is beyond the immediate context of the competencies of the organization and the ability to use it in different contexts are fundamental (Omidvar 2013).

The innovative performance of each organization depends on its absorptive capacity, which is positively related to the preexistent knowledge of the members of the organization. The absorptive capacity of the organization is directly linked to the individual capacity of each member (Cohen and Levinthal 1990) because the recipient of knowledge must have the skills and abilities to absorb it efficiently; otherwise, there will be a gap in this absorption (Tang 2011). This process of continuous refinement of knowledge occurs mainly through learning by doing (Omidvar 2013).

When the types of intellectual capital are associated with absorptive capacity, it is observed that relational capital has a relevant role in the absorptive capacity of the organization, because its improvement can generate practices that foster the transformation and exploitation of new knowledge (capacity performed), while the expansion of human capital encourages the acquisition and assimilation of new knowledge (potential capacity). Even socialization among the members of the organization is relevant to the realization of their absorptive capacity (Soo et al. 2017).

Therefore, companies with different absorptive capacities also have different levels of innovative performance (Ali et al. 2016; Zahra and George 2002; Cohen and Levinthal 1990). Also, innovative performance is the result of learning and the absorptive capacity of organizations (Ferreira and Ferreira 2017; Lane et al. 2006).

In family businesses, for example, members share memories and similar knowledge, especially regarding the organization, which help the innovative processes and the absorption of knowledge passed from one generation to the next (De Massis et al. 2016; Schmidts and Sheperd 2013). The absorptive capacity is, therefore, a relevant predictor of innovation in family businesses, and they have a recursive relationship (Ferreira and Ferreira 2017).

Studies on family businesses diverge on their innovative performance (Broekaert et al. 2016; Stenholm et al. 2016; De Massis et al. 2016; Miller et al. 2015). For this reason, in the next subtopic, the literature analysis will be deepened, presenting these studies on the innovative performance of family businesses.

2.3 Innovative Performance of Family Businesses

In a global environment with a rapid technological change, innovation is crucial for the growth and longevity of organizations, regardless of their size, sector, or species (Serrano-Bedia et al. 2016). Therefore, innovation is something new that generates value for the organization (Tidd and Bessant 2014). Innovation does not occur through a linear process; it is the result of the interaction between the organization and the environment. The ability of the company to achieve the objective through its activities is a way to measure the performance of its innovation (Ferreira and Ferreira 2017).

The organization being a family business is not a barrier to innovation (Leal-Rodriguez et al. 2017). Once the scope of this essay is directed to the innovation performance of family businesses, it is essential to clarify its concept. Chua et al. (1999) present how the business is governed and/or managed with the dominant view of the members of the same family(ies) throughout its generations. There are several other definitions; for example, it is stipulated that the company must be at least two generations within the family (Colli and Larsson 2014).

In these organizations, an adequate level of emotional connection between family and business is needed. Social identity facilitates integration between these areas, and there are three key dimensions to their development (Schmidts and Sheperd 2013): the level of involvement with the family business; shared memories, emotional connection; and the extent of the operation, represented by the number of family generations that the business exists (Schmidts and Sheperd 2013). The stories told by previous generations can be a mechanism to bring new generations closer to the company as well as to open the company to innovation (Kammerlander et al. 2015). This is innovation through tradition in family businesses, in other words, using the old knowledge of previous generations as an opportunity to create new products through a differentiated interpretation (value capture) of the past of the organization (De Massis et al. 2016).

On the one hand, there are characteristics in family businesses that hinder cooperation, such as avoiding risks and changes (Roessl and Rößl 2005). On the other hand, the family business has other characteristics that highlight innovation, such as its family character and entrepreneurship (Leal-Rodriguez et al. 2017) and its adaptability to discontinuous changes (König et al. 2013). Family businesses do have entrepreneurship orientation but need entrepreneurial activity in their strategies to overcome conservatism (Stenholm et al. 2016).

The propensity of family businesses to innovate is related to their purpose, that is, to propagate the internal interests of the family or the desire to create a robust business, those are averse to risk, having difficulty in innovating; these, in turn, invest in the organization, creating social and human capital that will allow innovation and prosperity (Miller et al. 2015). The human elements of these companies, their talents, interactions, and motivations, also indicate the possibility of innovation. Hence, there is a need for constant investment in intellectual capital (family and non-family) to develop and maintain the innovative capacity (Miller et al. 2015).

Corporate governance affects the nature and efficiency of family businesses (Csizmadia et al. 2016; Colli and Larsson 2014). For example, there is a positive relationship between the family nature of the organization and the disclosure of relational capital (Saleh and Masduki 2016). Furthermore, on the one hand, the family’s involvement in business might have a negative effect on innovative performance (Serrano-Bedia et al. 2016), both the family ownership and the generation (Decker and Günther 2017). On the other hand, the flexibility of the family business (Broekaert et al. 2016; König et al. 2013) including the ability to invest more in innovation in moments of calm and high reserves (Liu et al. 2017) affects the innovative performance of family businesses positively.

A crucial moment in the life cycle of family businesses is succession, a time when social and emotional wealth must be transmitted (Makó et al. 2016) and avoid its expropriation with the departure of the founder (Lwango and Coeurderoy 2004). In succession in family businesses, gender is also a relevant factor concerning succession by daughters and the preference for men in succession in family businesses (Hytti et al. 2017). With succession, there is a change in management, and there is an indication that the innovative performance of the organization will be changed (Makó et al. 2016; Csizmadia et al. 2016). The organization must develop a cohesive corporate culture and long-term investments to survive succession while maintaining its innovative performance (Miller et al. 2015).

3 Prior Evidence and Research Gap

After the explanations about intellectual capital, absorptive capacity, and innovative performance of family businesses, it can be observed that they are concepts related to each other. Thus, the absorptive capacity is substantially related to the relational capital in what concerns the cooperation for learning (Wexler 2002; Cohen and Levinthal 1990). Absorptive capacity and relational capital influence the innovative performance of organizations (Cohen and Levinthal 1990; Prod and Carlos 2015; Vlaisavljevic et al. 2016; Zahra and George 2002; Chitsazan et al. 2017). In the baseline studies on absorptive capacity, it is clarified that this is a condition for the innovation process (Cohen and Levinthal 1990; Zahra and George 2002).

Family ownership can be a factor of negative influence on innovative performance (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007; Breton-Miller et al. 2015; Kellermanns et al. 2012; Schulze and Kellermanns 2015; Decker and Günther 2017; Roessl and Rößl 2005; Serrano-Bedia et al. 2016) or not (Broekaert et al. 2016; De Massis et al. 2016; Kidwell et al. 2013; Leal-Rodriguez et al. 2017; Liu et al. 2017; Nordqvist and Melin 2010; Kellermanns et al. 2012).

About the gaps observed in this context, some are highlighted. The cultural context of these companies must be taken into account, as well as the number of generations passed by the organization (De Massis et al. 2016) and your time of activity. The industry also needs to be considered, as there are industries that need constant innovation, while others only take advantage of opportunistic innovation (Makó et al. 2016).

The immigration situation also presents itself as a relevant factor for the innovative performance of family businesses (Adendorff and Halkias 2014). There is also a need to differentiate between voluntary and forced immigration as a factor to entrepreneurship and innovation, as well as the degree of cultural difference between countries. Another observed gap is in the values of the family business, not only the moral values but also the ethical, spiritual, ecological, economic, and political values (Pedro 2014) because these values can influence the vision and innovative performance of the organization, as well as its capacity to absorb knowledge and its alliances. Most of the studies used the qualitative methodology utilizing a case study. It is also the most suitable method for analyzing complex situations and subjective contexts (Yin 2013; Godoy 1995) like family businesses. However, because of such gaps and divergences in the results of the case studies, there is a need to solidify the theoretical basis.

The relations are even clearer in the following table, which elucidates in a diachronic vision the studies about the influence of the intellectual capital on the innovative performance, the influence of the absorptive capacity on the innovative performance, and the innovative performance of family business (Table 1).

4 Conclusion

This essay was developed through a literature review. In the initial subtopics, it was presented that the absorptive capacity, as well as the social or relational capital, also influences the innovative performance of organizations (Chitsazan et al. 2017; Vlaisavljevic et al. 2016; Prod and Carlos 2015; Zahra and George 2002; Cohen and Levinthal 1990).

As far as family businesses are concerned, research shows that they are entrepreneurial and that they are focused on innovation (Leal-Rodriguez et al. 2017; Liu et al. 2017; Broekaert et al. 2016; De Massis et al. 2016; Kidwell et al. 2013; Kellermanns et al. 2012; Nordqvist and Melin 2010). The family ownership or if the organization has the influence of the family on management hinders its innovation performance (Decker and Günther 2017; Serrano-Bedia et al. 2016; Schulze and Kellermanns 2015; Kellermanns et al. 2012; Breton-Miller et al. 2015; Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007; Roessl and Rößl 2005).

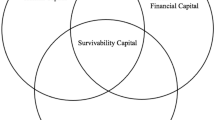

Hypotheses about the impact of each variable on the innovative performance of family businesses emerge. The role of absorptive capacity is not yet clear, i.e., whether it is moderating, mediating, or both simultaneously (Muller et al. 2005). For this reason, hypothesis 4 below is also necessary to identify whether the absorptive capacity affects the magnitude, direction, and/or strength of the relationship between intellectual capital and the innovative performance of family businesses (Fig. 1).

H1

Intellectual capital influences the innovative performance of family businesses.

H2

Intellectual capital influences the absorptive capacity of family businesses.

H3

The absorptive capacity influences the innovative performance of family businesses.

H4

The absorptive capacity has a moderating influence on the relationship between intellectual capital and innovative performance of family businesses.

The research about the relationship between intellectual capital and the absorptive capacity of family businesses for innovation performance must be improved. Therefore, the relationship between intellectual capital, absorptive capacity, and innovative performance in family businesses needs the attention of researchers so that there are relevant advances.

The main limitation of this research lies in its method, mainly due to the subjectivity of the author and lack of empirical testing. Therefore, regarding the scope of this essay, the test of the proposed model is suggested, and the effect of external influences on this relationship should be tested, such as values, culture, gender, industry, family hierarchies, and the number of generations. Qualitative methodologies are indicated to test the proposed model. For example, case studies on the relationship between intellectual capital and the absorptive capacity in the innovative performance of family businesses because it is a method to deeply understand complex events and contexts (Yin 2013; Godoy 1995).

Afterward, based on the previous studies that make up this study and, on the gaps, observed in the literature, the following suggestions are proposed for future researches:

-

1.

The role of organizational values in the relationship between the absorptive capacity and the innovative performance of family businesses.

-

2.

How the intellectual capital of immigrant family businesses influences their innovative performance.

-

3.

The influence of the values on the comparison between the innovative performance of immigrant and non-immigrant family businesses.

-

4.

The influence of the gender of the CEO on the innovative performance after the succession process in a family business.

-

5.

The above studies should also be carried out in family businesses in different cultural, geographical, sectoral, and financial contexts.

-

6.

Regarding the methodology, other methodologies should be explored, mainly longitudinal studies on the changes in the innovative performance of family businesses over the generations, principally on the influence of CEO exchanges.

References

Adendorff, C., & Halkias, D. (2014). Leveraging ethnic entrepreneurship, culture and family dynamics to enhance good governance and sustainability in the immigrant family business. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 19(02), 1450008. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1084946714500083.

Ali, M., Seny Kan, K. A., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). Direct and configurational paths of absorptive capacity and organizational innovation to successful organizational performance. Journal of Business Research, 69(11), 5317–5323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.131.

Andersén, J. (2015). The absorptive capacity of family firms: How familiness affects potential and realized absorptive capacity. Journal of Family Business Management, 5(1), 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940010305270.

Argote, L., & Ingram, P. (2000). Knowledge transfer: A basis for competitive advantage in firms. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 82(1), 150–169. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.2000.2893.

Breton-Miller, Le I., Miller, D., & Bares, F. (2015). Governance and entrepreneurship in family firms: Agency, behavioral agency and resource-based comparisons. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 6(1), 58–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2014.10.002.

Broekaert, W., Andries, P., & Debackere, K. (2016). Innovation processes in family firms: The relevance of organizational flexibility. Small Business Economics, 47(3), 771–785. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9760-7.

Chitsazan, H., Bagheri, A., & Yusefi, A. (2017). Intellectual, psychological, and social capital and business innovation: The moderating effect of organizational culture. Iranian. Journal of Management Studies, 10(2), 307–333. https://doi.org/10.22059/ijms.2017.215054.672249.

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., & Sharma, P. (1999). Defining the family business by behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(4), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879902300402.

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128–152.

Colli, A., & Larsson, M. (2014). Family business and business history: An example of comparative research. Business History, 56(1), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2013.818417.

Csizmadia, P., Makó, C., & Heidrich, B. (2016). Managing succession and knowledge transfer in family businesses: Lessons from a comparative research. Vezetéstudomány/Budapest Management Review, 47(11), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.14267/VEZTUD.2016.11.07.

Daspit, J. J., Chrisman, J. J., Sharma, P., Pearson, A. W., & Long, R. G. (2017). A strategic management perspective of the family firm: Past trends, new insights, and future directions. Journal of Managerial Issues, XXIX(1), 6–29.

De Massis, A., Frattini, F., Kotlar, J., Petruzzelli, A. M., & Wright, M. (2016). Innovation through tradition: Lessons from innovative family businesses and directions for future research. Academy of Management Perspectives, 30(1), 93–116. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2015.0017.

Decker, C., & Günther, C. (2017). The impact of family ownership on innovation: Evidence from the German machine tool industry. Small Business Economics, 48(1), 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9775-0.

Ferreira, G. C., & Ferreira, J. J. M. (2017). Absorptive capacity: An analysis in the context of Brazilian family firms. RAM. Revista de Administração Mackenzie, 18(1), 174–204. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-69712017/administracao.v18n1p174-204.

Godoy, A. S. (1995). Pesquisa Qualitativa Tipos Fundamentais. Revista de Administração de Empresas, 35(3), 20–29.

Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Takács Haynes, K., Núñez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K. J. L., & Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(1), 106–137. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.52.1.106.

Grant, R. (1996). Toward a knowledge based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17(17), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.2307/2486994.

Hernández-Perlines, F., & Xu, W. (2018). Conditional mediation of absorptive capacity and environment in international entrepreneurial orientation of family businesses. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00102.

Hytti, U., Alsos, G. A., Heinonen, J., & Ljunggren, E. (2017). Navigating the family business: A gendered analysis of identity construction of daughters. International Small Business Journal, 35(6), 665–686. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242616675924.

Ipe, M. (2003). Knowledge sharing in organizations: A conceptual framework. Human Resource Development Review, 2(4), 337–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484303257985.

Kammerlander, N., Dessì, C., Bird, M., Floris, M., & Murru, A. (2015). The impact of shared stories on family firm innovation: A multicase study. Family Business Review, 28(4), 332–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486515607777.

Kellermanns, F. W., Eddleston, K., Sarathy, R., & Murphy, F. (2012). Innovativeness in family firms: A family influence perspective. Small Business Economics, 38(1), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-010-9268-5.

Kidwell, R. E., Eddleston, K. A., Cater, J. J., & Kellermanns, F. W. (2013). How one bad family member can undermine a family firm: Preventing the Fredo effect. Business Horizons, 56(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2012.08.004.

König, A., Kammerlander, N., & Enders, A. (2013). The family innovator’s dilemma: How family influence affects the adoption of discontinuous technologies by incumbent firms. Academy of Management Review, 38(3), 418–441. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2011.0162.

Lane, P. J., Koka, B., & Pathak, S. (2006). The reification of absorptive capacity: A critical review and rejuvenation of the construct. Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 833–863. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2006.22527456.

Leal-Rodriguez, A. L., Peris-Ortiz, M., & Leal-Millan, A. G. (2017). Fostering entrepreneurship by linking organizational unlearning and innovation: The moderating role of family business. Management International, 21(2), 86–94. Retrieved from http://echo.louisville.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=122516548&site=ehost-live%0Ahttps://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=122516548&site=ehost-live.

Liu, Y., Chen, Y.-J., & Wang, L. C. (2017). Family business, innovation and organizational slack in Taiwan. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 34(1), 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-016-9496-6.

Lu, W. M., Wang, W. K., Tung, W. T., & Lin, F. (2010). Capability and efficiency of intellectual capital: The case of fabless companies in Taiwan. Expert Systems with Applications, 37(1), 546–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2009.05.031.

Lwango, A. B. R., & Coeurderoy, R. (2004). El capital social de la empresa familiar y la sucesion empresarial: un enfoque teorico.

Maak, T. (2007). Responsible leadership, stakeholder engagement, and the emergence of social capital. Journal of Business Ethics, 74(4), 329–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9510-5.

Makó, C., Csizmadia, P., & Heidrich, B. (2016). Succession in the family business: Need to transfer the ‘socioemotional wealth’ (Sew). Vezetéstudomány/Budapest Management Review, 47(11), 16–28. https://doi.org/10.14267/VEZTUD.2016.11.03.

Miller, D., Wright, M., Le Breton-Miller, I., & Scholes, L. (2015). Resources and innovation in family businesses. California Management Review, 58(1), 20–41. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2015.58.1.20.

Moutinho, R. F. F. (2016). Absorptive capacity and business model innovation as rapid development strategies for regional growth. Investigacion Economica, 75(295), 157–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inveco.2016.03.005.

Muller, D., Judd, C. M., & Yzerbyt, V. Y. (2005). When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(6), 852–863. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852.

Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. The Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242–266. https://doi.org/10.2307/259373.

Ngah, R., Salleh, Z., Ab Wahab, I., & Azman, N. A. (2016). Intellectual capital, knowledge management and sustainable competitive advantage on SMEs in Malaysia. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intellectual Capital, Knowledge Management & Organizational Learning (2000), pp. 348–356. Retrieved from https://liverpool.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=118716679&site=eds-live&scope=site

Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science, 5(1), 14–37. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.5.1.14.

Nordqvist, M., & Melin, L. (2010). Entrepreneurial families and family firms. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 22(3–4), 211–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985621003726119.

Núñez Ramírez, M. A., Nunez, J., Alejandro Banegas Rivero, R., & Nélida Sánchez Bañuelos, M. (2017). Structural relationship among intellectual capital dimensions. International Journal of Advanced Corporate Learning, 10(1), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijac.v10i1.6436. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=122257582&lang=pt-br&site=ehost-live

Omidvar, O. (2013). Revisiting absorptive capacity: Literature review and a practice-based extension of the concept. In 35th DRUID Celebration Conference, 31. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1802696.

Pedro, A. P. (2014). Ética, Moral, Axiologia E Valores: Confusões E Ambiguidades Em Torno De Um Conceito Comum. Kriterion: Revista de Filosofia, 55, 483–498. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-512X2014000200002.

Prod, G., & Carlos, S. (2015). Capital social em rede organizacional: Uma análise de suas dimensões explicativas.

Roessl, D., & Rößl, D. (2005). Family businesses and interfirm cooperation. Family Business Review, 18(3), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2005.00042.x.

Saleh, N. M., & Masduki, S. B. (2016). The influence of corporate governance on relational capital disclosure among high growth technology companies. Malaysian Accounting Review, 15(1), 29–62.

Sánchez-Sellero, P., Rosell-Martínez, J., & García-Vázquez, J. M. (2014). Absorptive capacity from foreign direct investment in Spanish manufacturing firms. International Business Review, 23(2), 429–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2013.06.006.

Schmidts, T., & Sheperd, D. (2013). Social identity theory and the family business: A contribution to understanding family business dynamics. Small Enterprise Research, 20(2), 76–86.

Schulze, W. S., & Kellermanns, F. W. (2015). Reifying socioemotional wealth. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(3), 447–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12159.

Serrano-Bedia, A. M., López-Fernández, M. C., & Garcia-Piqueres, G. (2016). Analysis of the relationship between sources of knowledge and innovation performance in family firms. Innovations, 18(4), 489–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/14479338.2016.1233826.

Soo, C., Tian, A. W., Teo, S. T. T., & Cordery, J. (2017). Intellectual capital-enhancing HR, absorptive capacity, and innovation. Human Resource Management, 56(3), 431–454. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21783.

Stenholm, P., Pukkinen, T., & Heinonen, J. (2016). Firm growth in family businesses-the role of entrepreneurial orientation and the entrepreneurial activity. Journal of Small Business Management, 54(2), 697–713. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12166.

Sulistyo, H., & Siyamtinah. (2016). Innovation capability of SMEs through entrepreneurship, marketing capability, relational capital and empowerment. Asia Pacific Management Review, 21(4), 196–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2016.02.002.

Tang, F. (2011). Knowledge transfer in intra-organization networks. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 282, 270–282. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.

Tidd, J., & Bessant, J. (2014). Strategic innovation management. Chichester: Wiley.

Van Den Bosch, F. A., Volberda, H. W., & Boer, M. D. (1999). Coevolution of firm absorptive capacity and knowledge environment: Organizational forms and combinative capabilities. Organization Science, 10(5), 551–568. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.10.5.551.Vega-Jurado.

Vlaisavljevic, V., Cabello-Medina, C., Ana, P., & Pérez-Luño, A. (2016). Coping with diversity in alliances for innovation: The role of relational social capital and knowledge codifiability. British Journal of Management, 27(2), 304–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12155.

Wang, S., & Noe, R. A. (2010). Knowledge sharing: A review and directions for future research. Human Resource Management Review, 20(2), 115–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.10.001.

Wexler, M. N. (2002). Organizational memory and intellectual capital. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 3(4), 393–414. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691930210448314.

Yin, R. K. (2013). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Yoo, S. J., Sawyerr, O., & Tan, W. L. (2016). The mediating effect of absorptive capacity and relational capital in alliance learning of SMEs. Journal of Small Business Management, 54, 234–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12299.

Zahra, S. A., & George, G. (2002). Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Academy of Management Review, 17(2), 185–203. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2002.6587995.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rocha, R.G., Leitão, J. (2020). The Innovative Performance of Family Businesses: An Essay About Intellectual Capital and Absorptive Capacity. In: Leitão, J., Nunes, A., Pereira, D., Ramadani, V. (eds) Intrapreneurship and Sustainable Human Capital. Studies on Entrepreneurship, Structural Change and Industrial Dynamics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49410-0_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49410-0_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-49409-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-49410-0

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)