Abstract

Health care students, including occupational therapy students, are required to use reflective practice in many coursework assignments, during their mandated clinical placements, and when practicing as health care professionals. The catalyst for this investigation was that university students are frequently required to complete these reflections in a written format. This is surprising, and contrary to clinical placements and practice, where the majority of reflection is undertaken either verbally with other health care professionals or via internal thought mechanisms (i.e. thinking about their thinking and decision making). After graduation from university, the use of written reflections is almost non-existent for health care practitioners. This chapter will argue that the commonly used written reflections do not mimic how reflection takes place during clinical placements and when working as a health care professional. The investigation described in this chapter aimed to identify the preferred method of reflection that third-year undergraduate occupational therapy students chose when offered a choice of reflective medium and to understand why they preferred the chosen format. Students who participated in our investigation could choose either a written, video or an artistic format to complete five reflective practice tasks. Students undertook a mandatory clinical placement where they spent a minimum of 75 h onsite at an aged care residential facility. During and after the placement, the students selected five topics from a list of 30+ topics that focussed their reflections on their effectiveness as an occupational therapist. For each topic, they were free to choose either of the three reflective medium formats. A total of 68 students completed an online survey, which collected quantitative and qualitative data. The 68 students completed a total of 340 reflective pieces with 81% preferring the video format, 18% selecting the written format, and only two students choosing an artistic format. Students reported that the video format was preferred because video required them to use verbal communication, which was the same method of reflection used during clinical placements. Video was also preferred because it allowed the full array of emotions to be expressed. The most commonly selected topics were “Critique your interpersonal, communication, and assertive skills” (57%) and “Critique your emotional resilience and coping skills” (43%). From the findings, the chapter, recommends that university educators shift from using written reflective assignments to verbal formats. The verbal format is both the preferred and most commonly used format of reflective practice used during clinical placement and in practice. Our results provide overwhelming evidence that students prefer the verbal format because they know that this is how reflection is completed in healthcare settings. Even those who preferred the written format agreed that the written expression of emotions is difficult and lacks sophistication when compared to the video format where the full set of emotional communication tools are available – words, facial gestures, body language, and voice pitch and intonation. University educators are encouraged to offer a choice of verbal and written reflective formats to students, with a requirement to complete most reflective tasks in the verbal format before commencing clinical placements. Our findings indicate that health care students prefer assignments to replicate the formats that they will encounter during clinical placements and when working as health care professionals.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Reflective Practice During Clinical Practice and Placements

Health care students , including occupational therapy students, are required to use reflective practice in many coursework assignments, on a daily basis during clinical placements, and when working as health care professionals. Reflection is the cognitive and affective processes that turn experience in the real world into learning that can be used in subsequent situations (Boud, Keogh, & Walker, 1985; Lavoué, Molinari, Prié, & Khezami, 2015). Sandars (2009, p. 685) defines reflection as, “…a metacognitive process that creates a greater understanding of self and situations to inform future action”. Reflection in health care professionals has been reported to enhance clinical reasoning, foster professional socialisation and identity , consider and resolve ethical issues, enhance critical thinking, and professional skills (Hill, Davidson, & Theodoros, 2012; Karen, Kimberley, & Sue, 2016; Mann, Gordon, & MacLeod, 2009). The outcome of using reflective practice can lead to a transformation within the health care professional, and if health care teams reflect together, this can lead to transformations in the effectiveness of the health care team (Miraglia & Asselin, 2015). Furthermore, for health care students reflection strengthens the linkages between theory and practice and leads to deeper self-awareness (Hill et al., 2012). Reflective practice is considered a critical ability for healthcare professionals as the self-critique process allows them to continually develop and refine their skills and clinical reasoning so that they deliver the highest level of service to their service users.

Reflective practice is considered a cornerstone of practice as it is embedded in many Australian health care professions’ competency standards. For example, the Australian Occupational Therapy Competency Standards requires that occupational therapists, “…reflect on practice to inform current and future reasoning and decision-making and the integration of theory and evidence into practice…” and that they “…reflect on practice to inform and communicate professional reasoning and decision-making” (Occupational Therapy Board of Australia, 2018, pp. 7–8). Furthermore, reflective practice is a critical employability attribute in the occupational therapy profession and across many health care professions (Dacre Pool & Sewell, 2007; Rodger, Fitzgerald, Davila, Millar, & Allison, 2011; Schell, 2009). Yorke (2006, p.8) has proposed that employability allows students to “…acquire the skills, understandings and personal attributes that make them more likely to secure employment and be successful in their chosen occupations to the benefit of themselves, the workforce, the community and the economy”. Dacre Pool and Sewell (2007) positions reflection as the pivotal process that transforms work experiences and ongoing career development courses into the self-belief, self-confidence and self-efficacy that enhances a person’s employability. The inclusion of reflective practice within the professional expectations and outcomes of university programs means that university educators have an obligation to teach and assess the skills that allow graduates from their programs to be active and competent reflective practitioners. As such, both coursework assignments and clinical placements are the most fertile ground for students to trial and refine their reflective practice skills.

Clinical placements are a mandatory element of occupational therapy programs where students are required to complete 1000 or more hours of clinical practice hours (World Federation of Occupational Therapists, 2016). During the clinical placements, occupational therapy students are progressively exposed to a variety of patients and healthcare settings where they work with problems of increasing complexity. Placements generally occur in all years of undergraduate therapy programs and tend to vary in length starting with short, primarily observation-based placements early in the program. Placements progress to full-time and can range from a few weeks to a few months in length depending on the university’s requirements. For many students, the scenarios they face during placements are new and challenging, meaning the use of reflective practice is frequent and indispensable during these formative experiences before graduation. For example, during a paediatric placement , an occupational therapy student might work with a child who struggles with social skills and their frustrated family; during an orthopaedic placement they might work with a patient who is in pain and distress; and during a mental health placement a patient may be hallucinating or be emotionally labile. Clinical practice confronts students with scenarios that are often complex. Thus, it is imperative that students understand that reflective practice is at the heart of developing professional expertise to cope and make decisions in these situations. In order to develop these invaluable skills, students should be made aware of the various types of reflective practice and when these are useful.

Schon (1987) has suggested that professionals use a combination of reflection types: reflection-in-action, which occurs during a task and reflection-on-action , which occurs after the task is completed. For a health care practitioner, reflection-in-action occurs during the task and allows the practitioner to make adjustments or modify the treatment session in real-time (Lavoué et al., 2015). A health care practitioner might use reflection-in-action during a treatment session when something different, unexpected, or unusual occurs. For example, a patent might react in an unexpected way to a treatment modality which results in the practitioner needing to change the treatment session from what was planned. Reflection-on-action, which occurs after completing a task, has been described as having three components: (i) reviewing the experience and replaying what occurred; (ii) evaluating the success of the session, acknowledging the emotional aspects, and drawing on knowledge and/or theory, which results in (iii) the creation of new approaches for future similar tasks (Lavoué et al., 2015). Reflection-in-action is perhaps a more complex skill than reflection-on-action, as reflection-in-action requires the practitioner to consider whether changes alternative in real-time.

Health care students are novice practitioners and will tend to find reflection-in-action more difficult (Hill et al., 2012). Students need time during clinical placements to acclimatise to the routines and practices of each health care setting. Students need time to understand the array of assessments and interventions that are appropriate with the patients they work within each setting. On a daily basis, students observe their supervisors or other professionals in action where they learn more skills and start to understand the commonly used assessments and interventions that might be beneficial with each patient. Thus, early in placements students have a minimal number of alternative modalities to draw from when something unexpected or challenging occurs. Without an expansive set of contingency ideas, students are less likely to engage in reflection-in-action (Hill et al., 2012). As such, students are more likely to use reflection-on-action. During a clinical placement , a student will undertake a session with a patient. Afterwards they should be encouraged to think about the session and what worked and how the session might have been improved. When the time is right, they should reflect verbally with their supervisor about whether the assessment or intervention session was successful. The student and supervisor will discuss tips and ideas for improvements for the next time or ways to modify their body language to enhance rapport building. They might discuss the student ’s emotions and reactions to the situation. The student will then think and mull over the discussion, clarifying in their own mind the key points that they did well and other areas to change their practice next time a similar scenario presents. These reflective discussions could take a few minutes or longer, or they could be scheduled to occur at specific points on a daily basis. In different practice settings, there will be more or less time for this type of discussion dependent on how busy the daily schedule. In summary, during clinical placements, students will tend to use reflection-on-action using a combination of metacognitive and verbal formats.

In today’s demanding health care settings, most practitioners, including occupational therapists, simply do not have the time to write or type up their reflections. When 842 general practitioners were asked which format of reflection they found most useful, 84% reported that verbal reflection was preferred over written reflection (Curtis, Taylor, Riley, Pelly, & Harris, 2017). Reflection-on-action demands a time commitment, which is often challenging for today’s health care professional to find. Professional competency standards compel practitioners to reflect on their practice before, during, and after interactions with patients as well before, during, and after interactions with their health care team. Another study (Cain, Le, & Billett, 2019) surveyed students about their preferred method for debriefing after practicums. The findings indicated that the students had a strong preference for face-to-face interactions such as small groups or one-on-one with teachers or lead by experienced students. That is, the preference was for verbal reflection . As such, health care professionals tend to either think about their practice or talk to colleagues or other experienced practitioners in order to improve their practice, skills, attitudes, and behaviours.

Contrary to the above findings from clinical practice, university educators tend to demand a written format for reflective practice assignments. The use of written reflections allows students to take their time to understand the theoretical foundations of their selected or preferred reflective model. For example, Gibbs Reflective Cycle is a model that is frequently taught across healthcare programs (Larkin & Pepin, 2010). A multitude of written formats are used to develop and assess health care students’ reflective practice skills (Stagnitti, Schoo, & Welch, 2010; Tan, Ladyshewsky, & Gardner, 2010). A systematic review of reflective practice identified that written journals, portfolios, blogs, questionnaires, and diaries are frequently used with students to record their reflections (Tsingos, Bosnic-Anticevich, & Smith, 2015). As such, written reflection may be useful in the early stages of learning reflective practice. However, as written reflection does not mirror how the majority of reflection occurs during clinical practice, reflection should transition to verbal and metacognitive formats as full-time clinical placements approach.

Given the evidence that verbal reflection is more common in clinical practice, as well as the preferred method in clinical placements, university educators need to rethink the tendency to require students to use a written format for reflections. The vast majority of previous research on university students’ reflective practice analysed reflections that are presented in a written format (Fragkos, 2016) and more research is needed into the use or video or audio formats for reflection . No previous studies were identified that offered university students a choice of format when using reflection-on-action or investigated why students might choose verbal or written formats when offered the choice.

The following section outlines an assignment task that offered occupational therapy students a choice of reflective format during and after a clinical placement .

2 The Project

The aim of our project was to determine the preferred method of reflection of third-year occupational therapy students when offered a choice of written, video, or an artistic format. Furthermore, the project investigated why students selected the written, video, or artistic format and the benefits and problems with each format. The students in our study were also offered a choice of topics on which to base their reflections, and the project also determined which of these topics students selected.

2.1 The Clinical Placement

Participants in the study were third-year occupational therapy students enrolled in the undergraduate Bachelor of Science (Occupational Therapy) program at one Australian university. The learning outcomes for this unit were for students to: demonstrate professional behaviours and accountability; demonstrate clinical reasoning to a professional standard in a health or human service context; form a productive therapeutic relationship with health consumers; demonstrate ethical practice; and central to our study, to critically reflect upon clinical experiences. The unit consisted of 12 two-hour weekly tutorials and 75 h of clinical placement which occurred over a 12-week period.

During the clinical placement, students spent 1–2 days per week at an aged care residential site and had to submit timesheets totalling 75 h or more by the end of the semester. The placements were designed to be student-lead. Students were allocated an on-site staff member who provided some basic orientation to the facility and introduced the residents to the students. In most sites, an occupational therapist undertook this role, but in other sites, a physiotherapist or nurse assisted the students. Students worked in pairs. Each pair was allocated four residents. Students managed their own caseload, i.e. if a resident passed away or withdrew from the program, the students were allocated new residents. With each of the four residents, the occupational therapy students were expected to develop rapport, complete a few appropriate assessments (e.g. conduct an initial interview with the resident and/or family; Canadian Occupational Performance Measure; functional assessment; leisure checklist) and interpret the assessment results. Then, in collaboration with the resident, family, or staff, create realistic occupational goals that could be achieved over the 12 week period. The students then trialled and implemented strategies to assist each resident towards the achievement of their goals. In the final weeks of the placement , the students evaluated the outcomes of the program and handed any sustainable interventions over to family or staff.

Students attended a two-hour tutorial at the university campus each week for 12 weeks. The majority of the tutorial was dedicated to debriefing and discussion about the clinical placement , residents, and occupational therapy practice. The relatively unstructured tutorial set-up allowed students to share assessment and intervention ideas, discuss challenging scenarios, debate ethical dilemmas, verbalise their clinical reasoning, and learn from each other and the occupational therapist who facilitated the tutorials.

2.2 The Reflective Practice Task

Students completed five reflective pieces during and after the clinical placement , as such, the task called for reflection-on-action. Two of the five reflections were submitted in Week 7 of the semester so that students could receive and learn from the feedback. The remaining three reflections were submitted after the completion of the 75 h of placement .

Providing a specific purpose for the reflective task is seen as critical so that students foster and build their reflective practice skills (Sandars, 2009). As such, the purpose of each reflective piece was for each student to (i) critique their effectiveness as an occupational therapist and (ii) to critique their clinical reasoning during the clinical placement .

For each reflective piece, students were required to select a topic from a list of 32 topics. (see Appendix A for the full list of topics), with the option to create their own topic. Topics ranged from ‘critique your assertiveness skills’ to ‘critique why you became frustrated during the placement ’ or ‘critique your teamwork skills’. Students then identified and described a critical incident or significant event that occurred during the clinical placement that related to the topic. The critical incident or significant event could have occurred during any interaction with a resident, during an assessment or intervention session/s, when interacting with a staff or family member, or a series of events that occurred over time. The reflective component required the student to discuss what they learnt personally and professionally and to show insight into their emotional reaction to the critical incident or significant event. They were also required to integrate some evidence-based practice and relevant theory. The incorporation of evidence and theory provides the opportunity for the student to gain a deeper insight or new perspective of the critical incident or event. Finally, they were required to research and create an array of strategies they would use to enhance their future practice or deal with a similar critical incident or event in the future. The length of each reflective piece was at the students’ discretion. Reflections were uploaded to the unit’s course management system site for marking. Marks were weighted towards the integration of theory and evidence and students’ planned future actions.

The steps detailed above follow an approach suggested by Sandars (2009) who purported that guided reflection, in our case, the use of suggested topics to drive the reflection combined with the above set of guiding steps, is beneficial in students developing their own reflective practice skills. Sandars (2009) also suggests that reflection should be completed repeatedly. In our case, students completed two of the reflective pieces at the mid-semester point, then received feedback, and then completed three more reflective pieces, and then more feedback. Sandars (2009) also suggested that students should seek further knowledge or information about the incident or event assists in developing professional expertise. In our case, students integrated research about theory or evidence related to the selected topic and/or events into their reflective piece.

Of importance to the study, students were given a choice of the medium they used for the reflective task. For each of the five reflective pieces, students could choose either video, written, or an artistic medium. Students could change the format for each separate topic or use the same format for all five topics. For example, a student could select the written format for three topics, video for another, and artistic for the final topic; or any combination. For the video format, students were instructed to video themselves talking directly to a camera. They could speak in first-person. Videos were submitted via YouTube (set to Unlisted) or any similar cloud-storage site. For the written format, written pieces could be typed or handwritten and could use first-person. For the artistic format, students were told that they could use any artistic medium that they felt suited their critique and learning style — for example, poetry, painting, drawing, dancing, or song. The artistic piece could also include a written response. For all formats, the unit outline instructed the students, to be brutally honest and to show their emotions. University educators who are embedding reflective assignments into a clinical placement are encouraged to detail a specific purpose of the reflective task that is meaningful to their students. In our case, we asked students to focus on their effectiveness and clinical reasoning as novice occupational therapists. Another recommendation is to weight the assessment of reflection towards the future-oriented actions that the students create, rather than weighting assessment towards the retelling of an incident. In our case, we allocated 80% of the marks to these sections. We also offered the students a large selection of topics so they could focus on elements of their practice that were of concern or important to them. The unique aspect of our study was allowing the students to choose their preferred format. The findings from our analysis of the submitted reflections are presented in the following section.

2.3 Data Collection

The proposed research study received ethics approval from the university’s Human Research Ethics Committee.

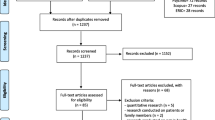

The study used a mixed methods design whereby quantitative and qualitative data were collected at the same time using the online Qualtrics website. A research assistant emailed all 140 students enrolled in the unit, inviting them to participate. Four email reminders were sent over a 4 week period. Students were presented with a Participant Information Sheet and provided consent at the beginning of the online survey . The online survey asked the following: enrolment status in the unit, age, gender, previous clinical placements in aged care, the format selected for each of the five topics, and topics selected. Participants also used text to write their responses to questions about why they selected the format, challenges and benefits of the selected format, and why they selected each topic.

The reflective pieces were submitted as assessable tasks during Semester 2 of 2017. Data for the study was analysed after the semester was finished, the clinical placements were completed, and all student grades were processed and finalised. The quantitative data were analysed using Excel and consisted of descriptive statistics such as counts, means, and standard deviations. The qualitative data was entered into the QSR International NVivo 10 Software package for thematic analysis and identification of themes (NVivo, 2012).

2.4 Participants

Sixty-eight students (63 female; 5 male) consented and completed the online survey representing a response rate of 49% of the students enrolled in the unit.

Students were asked about their previous work and experiences in aged care facilities. Only one student was currently employed in the aged care sector, and three had previously worked in the aged care sector. Eighteen students (26%) had never been into an aged care facility prior to this clinical placement . As the purpose of the study was to investigate the preferred format of reflection , thus all those students with current or nil previous experiences in aged care facilities were retained in the data analysis.

3 The Preferred Format for Reflective Practice

Each of the 68 students submitted five reflective pierces for a total of 340 reflective pieces. Table 1 summarises the format the students selected. Video was the overwhelmingly preferred format with 276 of the 340 reflections (81%) being submitted in this medium. Only four (0.01%) of the reflections used the artistic format.

The following section will summarise the benefits and negatives of each format using direct quotes from the students.

The video format was the most preferred format of the reflective pieces. The most common reasons reported for selecting video was that video allows for the natural and authentic expression of emotions. Video also allows the student to present more detail about the incident, event, or resident because they can use an array of verbal and non-verbal language including facial expressions and hand gestures that add depth in a short amount of time. Speaking uses the same format of reflection and clinical reasoning used during clinical placements with supervisors, peers, and other health professionals. Video was reported by all students to be quicker to complete compared to the written format.

The following quotes highlight that students found the video format allowed for more natural expression of an array of emotions.

“The emotional context and aha moments were easier to portray in video than in written format” (Subject 20).

Video was the “…truest way to show my ups and downs while working through the incident that occurred” (Subject 41).

“I also found that I was much more likely to be honest in a video rather than writing, as with a video once it was done it was done, it was honest and a true reflection, whereas with a written reflection I could have edited out anything I did not want to include” (Subject 47).

These quotes show that students found the video format allowed for a more authentic and faithful expression of emotions compared to writing, where expressing emotions in the written format was complex and required advanced technical writing skills. Students stated that because they could actively use facial expressions, hand gestures, non-verbal body language, changes in tone and pitch of the voice, and show their own personality, video was a more natural way of communicating emotions to the assessor than written. Many students stated that video allowed them to be honest and express a vast array of emotions using verbal and non-verbal language. The majority of students agreed that it was easier to express negative emotions such as anger, disappointment, dissatisfaction, or frustration, which could have been conveyed by banging the desk, shrugging the shoulders, or changing the pitch and intonation of their voice. On the other hand, students also reported that video allowed them to express an array of positive emotions easier. They reported being able to express genuine concern and compassion for the resident.

Students reported selecting video as it uses the same medium that is required during day-to-day practice in health care settings and with supervisors. Students stated that video allowed them to build confidence in using occupational therapy specific terminology they would be required to verbalise during clinical placements. Using video reflections “…increased my confidence in speaking like an OT” (Subject 12).

Students reported that video was a quicker medium, compared to writing, to explain the background story or context. Students said that writing the same story was tedious and time-consuming. Verbally telling a story was reported to be much quicker than typing, because writing required multiple edits and re-writes to give an accurate portrayal of the background story or context. As this student wrote, “I didn’t have to be perfectly correct as I could self-correct when speaking” (Subject 3). This view is consistent with that proposed by Curtis et al. (2017, p. 141) investigation of 842 general practitioners with the authors stating “…written reflection is an onerous process rather than being beneficial to their learning…”.

Some students reported that they recorded the videos multiple times and edited together their preferred responses. These students reported that they felt that re-watching and re-recording their videos heightened the depth of reflection that occurred. Students benefitted from watching and listening to their video reflections. As this student noted, “As a result of recording my critiques I was able to replay my video and further reflect on my performance and how I could improve in the future” (Subject 35). Students who used the written format did not report this reinforcement or amplified sense of reflection . Perhaps, when students are editing written work are focussed on spelling and grammar, whereas when reviewing and re-recording video, the students are more focussed on the background and reflection .

The negatives of using the video format included software and technical problems, including having no previous experience using video software, the time it took to edit the video into the final version, and interruptions from family members in the middle of video recording. Some students stated they did not like having to listen to their own voice and that videoing was not a usual format used for assignments.

In summary, the video format was selected for 81% of reflective pieces because the verbal format corresponds to the format used during clinical placements with supervisors, peers, and other health care professionals. An important finding is that all students reported that video allowed the expression of real emotions through multiple communication channels, words, facial, body, and voice, whereas written formats allow emotions to be expressed using words only.

The written format accounted for 18% of the reflective pieces. The main reasons for selecting the written format was that writing was a more manageable format to edit and correct mistakes compared to the video format; and that the written format was reported as safer for students who lacked confidence in verbalising their thoughts.

Students reported that writing allowed them to rapidly edit spelling and grammar errors compared to video where they felt they would have to re-record the entire response. Students who preferred the written format reported they could rapidly and efficiently proofread their responses and insert new ideas or thoughts. Whereas inserting new ideas was difficult and time-consuming when using video format. For example, this student felt reassured by the ability to edit their written work. “I could perfect my critique easier than having to re-record every time I made a mistake” (Subject 51). This quote may also indicate that students seeking to be perfectionistic may tend to use the written format as it offers more control over the final product compared to the verbal format.

Another reason for the preference for the safer written format was that, concerningly, a few students felt under-confident in verbalising their reflections and thus preferred the written format.

“I am not a confident speaker and still needed to pre-plan what I wanted to say in detail, so written critiques ended up being quicker for me to produce than video” (Subject 40).

This statement should be of concern to the university educators as well as the student, especially given that occupational therapy students are expected to communicate verbally for the vast majority of clinical placements. As a result, university educators are encouraged to move assessments towards a more verbal format as the full-time clinical placements approach in the final years of the university program.

Students who selected the written medium identified the following negatives to this format. The students noted the extended time required to write, proofread, and edit a comprehensive written reflection . They also agreed that it is complex using written language to express the authentic and complex array of emotions that incidents and events produce during clinical placements. As this student stated, “When writing, the assessor can’t see facial expressions or hear the tone of voice, which adds value and context to a critique” (Subject 49).

In summary, it is interesting to note that even those who preferred the written format agreed that the written expression of emotions is difficult and lacks sophistication when compared to the video format where the full set of emotional communication tools are available – words, face, body, and voice. Feelings and emotions are a part of many of the reflective practice model (e.g. Gibbs). The data we have obtained for this study is reinforcing the idea that to reflect fully requires the expression of a full set of emotions, which is easier done via verbal and non-verbal communication channels.

Only two students selected the artistic format with a total of four reflective pieces. All four artistic pieces were presented as songs with the student playing their guitar. They had composed the lyrics and music themselves. They reported that the musical format utilised their hobby and kept them engaged in the reflective task. As this student wrote, “I enjoy singing and playing music and this was a way I could use that while thinking about situations and writing about them and then singing them” (Subject 66). Other students reported they did not use the artistic format, despite wanting to, because it was not a method of reflection that was used during clinical placements. Although the health care sector may be in need of more creativity in its day to day operations, the use of artistic formats for reflection such as songs or poetry does not have a place. However, students who learn through more creative mediums should be encouraged to create poetry, songs or artwork as a way of expressing their emotions related to the scenarios they face on placements – although these should probably be done at home and not in the workplace.

4 Preferred Topics for Reflection

Students were given a comprehensive list of 32 potential topics to choose from with the option to create their own topic. See Appendix A for the full list of topics. For each of the five reflective pieces, students selected a topic and then identified a significant event or incident that occurred and then created their response. Table 2 presents the most commonly selected topics. Table 3 presents the topic that students reported as being the most useful. Students could only select one topic.

The three most common selected topics were ‘Critique your interpersonal, communication, and assertive skills’ with 57% of students choosing this topic, ‘Critique your emotional resilience and coping skills’ (43%), and ‘Critique an intervention you implemented with a resident’ (40%). The least selected topics were ‘Critique how you dealt with an ethical issue’ (15%) and ‘Reflect on your preparedness for 4th year full-time clinical placements’ (15%). Exactly the same as the most commonly selected topics, the three topics considered the most useful were ‘Critique your interpersonal, communication, and assertive skills’, ‘Critique your emotional resilience and coping skills’, and ‘Critique an intervention or assessment you completed with a resident’.

The most commonly selected topics align with the demands of clinical placements, in that communication skills, emotional resilience, and intervention planning make up a large component of the daily work during occupational therapy placements. These results are also useful to university educators in that students prefer to reflect on topics that impact their day to day work task that they face during placements. It should be a concern to university educators that students appeared hesitant to select the topic “Critique your use of evidence-based practice”, as this should be one of the highest priorities to novice practitioners.

The students reported the ‘interpersonal, communication, and assertiveness topic’ as the most useful because the clinical placement had highlighted that their communication skills were far from fully matured. As this student stated, “…because communication skills are important to have in all fields of OT. You can have solid ideas on interventions but may not be able to deliver it properly because you may lack the interpersonal skills” (Subject 30). In regard to assertiveness, students reported that they thought they were able to be assertive at their place of paid employment or with family members, but being assertive in a team of experienced health care professionals was far more complicated than they had imagined. This student stated, “I thought I was assertive before starting placement but quickly realised I’m not and this critique helped me realise why and what I need to do to change” (Subject 53). A study that investigated the impact of clinical placements on therapy students’ emotional intelligence (Gribble, Ladyshewsky, & Parsons, 2017) also reported students’ diminished confidence to be assertive during a clinical placement compared to their personal life. Students reported the ‘emotional resilience and coping skills’ topic to be useful was because they realised they needed to mature in order to deal with the emotionally complex scenarios that clinical placements presented to them, as this student stated:

“Because I had not really thought too deeply about my emotional resilience prior to this and how much it would impact my practice as an OT. Therefore this gave me the opportunity to explore the topic more, my strengths and weaknesses and how I can change” (Subject 39).

Another student stated, “…it (the reflection ) made me address some internal struggles/grief that I needed to resolve in order to the best OT I can be” (Subject 38). Perhaps these students are also suggesting to university educators that more skill development is needed in the occupational therapy program to develop the array of emotional resilience skills need to cope with the emotional demands of clinical placements.

Given the importance of the communication and emotional resilience topics, it is not that surprising that the preferred format for reflecting on these skillsets was the verbal format that allowed for more expansive emotional expression. And in the process of reflecting on their communication skills, the video format also gave them a place practice their communication skills.

5 Recommendations for University Educators

When setting assessments that include a reflective practice component, either before or during clinical placements, university educators are encouraged to use the following recommendations that have emerged from the analysis of our survey results.

University educators should offer a choice of reflective format – video or written. Our findings suggest that when students complete reflection-on-action assignments, video will be the preferred method if they are offered a choice. Students will tend to choose the format that aligns to their learning needs and hastens the speed of completing the reflective tasks. More so, if university educators expect that the feelings and emotions that are often a part of the reflective models, then video format allows a more authentic expression of these emotions, compared to the written format that requires more technical skill in expressing authentic emotion. Tsingos et al. (2015, p. 499), who investigated pharmacy students, concurs with the benefits of video reflection stating “…self-reflection through media such as video, can empower a student to view first hand his/her approaches to the task…”. Our results indicate that the use of artistic formats of reflection should be avoided as they do not match how reflection is undertaken during clinical placements.

University educators should ensure that a large percentage of reflective tasks are completed in a verbal format, especially in units leading up to clinical placements so that students practice verbalising reflections and clinical reasoning. Students who identify as under-confident in using video formats should be encouraged to practice using the verbal format more often in order to rehearse for clinical placements. Curtis et al. (2017) agree, and go as far to recommend that the use of written reflection as a mandatory part of the licencing of general practitioners in the United Kingdom needs to be critically examined. The views of the students in our study align with Grant, Kinnersley, Metcalf, Pill, and Houston (2006) who reported that general practitioners tended not to be engaged in written reflective tasks because this format does not align with the realities of clinical practice. Their study reported that 85% of general practitioners agreed that there are better uses of their time than doing written reflections.

When setting reflective practice assignments, the university educator should clearly describe the purpose of the reflection so that students engage and understand the outcomes of repeatedly practicing reflection . In our investigation of occupational therapy students, the purpose of the refection was to critique their effectiveness as an occupational therapist and to critique their clinical reasoning skills. Reflective tasks should be guided, by providing step by step processes, as suggested by Sandars (2009) or a list of suggested topics to link to critical events or incidents that occur during placements. The list of 33 topics that our students could select from is in Appendix A.

University educators are encouraged to provide more opportunities for students to develop skills to deal with the emotional events (e.g. patients in pain or vulnerable) and scenarios that require students to be assertive with experienced health care professionals (e.g. being forthright and honest in a team meeting).

Further research is recommended to investigate if video is the preferred method of refection in other student cohorts in the health and all other professions. The use of audio could also be explored, although video still offers more of the authentic human channels for exhibiting emotions than audio.

6 Conclusion

This study adds new knowledge about the preferred methods of reflection for occupational therapy students during and after clinical placements. The overwhelming preferred method of completing reflective practice tasks was using a video format, which aligns to ways that practitioners reflect during day-to-day practice. Most importantly, video allowed students to practice reflective tasks using the same format as is used during placement , namely speaking. University educators are encouraged to offer students a choice of reflective practice medium but to ensure that those students who are under-confident in verbalising their reflection use the video format, as this is the method they use during clinical placements and when the practice after graduation.

Video allowed students to use natural spoken language in combination with the ability to authentically express an array of complex emotions, in a relatively short period of time. Humans express emotions through numerous channels, and the students agree that the written format does not allow for a full array of emotions to be described (except if the student has exceptional technical writing skills). During placements, the majority of scenarios that student may want to reflect on are awash with emotional data and using verbal and non-verbal forms of communication are by far the easiest way to ensure these essential human emotions remain integral to the reflective process.

University educators have an obligation to assist students in learning how to be competent and proficient reflective practitioners before they enter the demands of clinical practice. They can assist students by engaging them in the kind of thinking and acting that will be required for their work, and this includes the kind of problem-solving, rationalising, decision-making and evaluation of their practice that reflective practice secures when done well. At the heart of our argument in this paper is that any reflective assessment should replicate the way that humans express emotions and how reflective practice happens in day-to-day practice. As such, university educators are encouraged to move assessments towards a more verbal format as the full-time clinical placements approach in the final years of the university program.

References

Boud, D., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (1985). Reflection: Turning experience into learning. (D. Boud, R. Keogh, & D. Walker, Eds.). London, UK: Kogan Page.

Cain, M., Le, A. H., & Billett, S. (2019). Sharing stories and building resilience: Student preferences and processes of post-practicum interventions. In S. Billett, J. Newton, G. Rogers, & C. Noble (Eds.), Augmenting health and social care students’ clinical learning experiences: outcomes and processes (pp. 27–53). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Curtis, P., Taylor, G., Riley, R., Pelly, T., & Harris, M. (2017). Written refection in assessment and appraisal: GP and GP trainee views. Education for Primary Care, 28(3), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2016.1277168

Dacre Pool, L., & Sewell, P. (2007). The key to employability: Developing a practical model of graduate employability. Education + Training, 49(4), 277–289. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910710754435

Fragkos, K. (2016). Reflective practice in healthcare education: An umbrella review. Education Sciences, 6(27), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci6030027

Grant, A., Kinnersley, P., Metcalf, E., Pill, R., & Houston, H. (2006). Students’ views of reflective learning techniques: An efficacy study at a UK medical school. Medical Education, 40(4), 379–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02415.x

Gribble, N., Ladyshewsky, R. K., & Parsons, R. (2017). Strategies for interprofessional facilitators and clinical supervisors that may enhance the emotional intelligence of therapy students. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 31(5), 593–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1341867

Hill, A. E., Davidson, B. J., & Theodoros, D. G. (2012). Reflections on clinical learning in novice speech-language therapy students. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 47(4), 413–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-6984.2012.00154.x

Karen, Y., Kimberley, J., & Sue, N. (2016). Exploration of a reflective practice rubric. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 17(2), 135–147.

Larkin, H., & Pepin, G. (2010). Becoming a reflective practitioner. In K. Stagnitti, A. Schoo, & D. Welch (Eds.), Clinical and fieldwork placements in the health professions (2nd ed.). Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press.

Lavoué, É., Molinari, G., Prié, Y., & Khezami, S. (2015). Reflection-in-action markers for reflection-on-action in computer-supported collaborative learning settings. Computers & Education, 88, 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.05.001

Mann, K., Gordon, J., & MacLeod, A. (2009). Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: A systematic review. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 14(4), 595–621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2

Miraglia, R., & Asselin, M. E. (2015). Reflection as an educational strategy in nursing professional development. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 31(2), 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/NND.0000000000000151

NVivo. (2012). NVivo qualitative data analysis software: version 10. QSR International Pty Ltd.

Occupational Therapy Board of Australia. (2018). Australian occupational therapy competency standards 2018. Retrieved from http://www.occupationaltherapyboard.gov.au/Codes-Guidelines/Competencies.aspx

Rodger, S., Fitzgerald, C., Davila, W., Millar, F., & Allison, H. (2011). What makes a quality occupational therapy practice placement? Students’ and practice educators’ perspectives. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 58(3), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2010.00903.x

Sandars, J. (2009). The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE guide no. 44. Medical Teacher, 31(8), 685–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590903050374

Schell, B. A. (2009). Professional reasoning in practice. In E. B. Crepeau, E. S. Cohn, & B. A. Schell (Eds.), Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy (11th ed., pp. 314–327). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Schon, D. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Stagnitti, K., Schoo, D., & Welch, D. (2010). Clinical and fieldwork placements in the health professions (2nd ed.). Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press.

Tan, S. M., Ladyshewsky, R. K., & Gardner, P. (2010). Using blogging to promote clinical reasoning and metacognition in undergraduate physiotherapy fieldwork programs. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 26(3), 355–368. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1080

Tsingos, C., Bosnic-Anticevich, S., & Smith, L. (2015). Learning styles and approaches: Can reflective strategies encourage deep learning? Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 7(4), 492–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2015.04.006

World Federation of Occupational Therapists. (2016). Minimum standards for the education of occupational therapists (2016 revision). London, UK: The Council of the World Federation of Occupational Therapists.

Yorke, M. (2006). Employability in higher education: What it is – What it is not (Learning and employability series 1). York, UK: The Higher Education Academy. Retrieved from https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/id116_employability_in_higher_education_336.pdf

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix A

Appendix A

The 33 topics that students could select from:

-

1.

Critique your use of evidence-based practice.

-

2.

Critique your emotional resilience and coping skills.

-

3.

Critique your interpersonal, communication, and assertive skills.

-

4.

Critique your initial interview skills.

-

5.

Critique your ability to explain occupational therapy to your residents.

-

6.

Critique your first two days on the placement.

-

7.

Critique an assessment that you completed.

-

8.

Critique your ability to interpret information from assessments.

-

9.

Critique your ability to assess occupational performance.

-

10.

Critique a set of progress notes

-

11.

Critique the occupation-based goals that were set

-

12.

Reflect on how you coped when receiving feedback.

-

13.

Critique a clinical decision you made.

-

14.

Critique your clinical reasoning skills.

-

15.

Critique a group activity/session you facilitated.

-

16.

Critique an intervention you implemented with a resident.

-

17.

Critique your ability to deal with stress.

-

18.

Critique why you became frustrated or annoyed during the placement?

-

19.

Critique your time management and organisational skills.

-

20.

Critique your teamwork skills.

-

21.

Critique your confidence in making decisions.

-

22.

Critique how you dealt with an ethical issue.

-

23.

Critique how you dealt with elder abuse – if you observed it.

-

24.

Did one of the residents pass away during your time in the facility? How did you react?

-

25.

Did you have a strong emotional reaction to something that occurred?

-

26.

Critique your ability to deal with workplace politics.

-

27.

Critique how you evaluated the outcome of the OT program.

-

28.

Critique how you concluded the therapeutic relationships at the end of the placement?

-

29.

If you worked on a project, critique the outcome.

-

30.

Select any item or set of items on the SPEF-R. Critique your skills in this area.

-

31.

Critique how you used OT theory during the placement, e.g. OT model, CPPF, occupation as core to occupational therapy etc.

-

32.

Reflect on your preparedness for your 4th-year full-time clinical placements.

-

33.

Other topic was chosen – use free text.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Gribble, N., Netto, J. (2020). The Preferred Method of Reflection for Occupational Therapy Students During and After Clinical Placements: Video, Written or Artistic?. In: Billett, S., Orrell, J., Jackson, D., Valencia-Forrester, F. (eds) Enriching Higher Education Students' Learning through Post-work Placement Interventions. Professional and Practice-based Learning, vol 28. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48062-2_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48062-2_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-48061-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-48062-2

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)