Abstract

This chapter describes a two-pronged strategy trialled with final year public health and environmental health students transitioning to professional work. The first component acquaints students with the principles and practices required for effective transition, including self-efficacy, developing a professional identity and building resilience. The second, introduces learning circles as a means of fostering critical thinking (Hiebert, Nurse Educ 21(3):37–42, 1996) and peer learning. Reflection is widely recognised as being critical for deep learning and learning circles are emerging as a strategy to enable student reflection. It is therefore timely to explore what learning circles can offer students, and what critical factors enable their successful use for student development while on placement. This chapter reports on a study that tracked the introduction of learning circles into two academic programs that provided intentional in- class activities for two cohorts of final trimester students to reflect on, and share their learning while enrolled in practicum. Data were obtained through a variety of means. Pre and post surveys, based around the constructs of professional identity, resilience, and self-efficacy, used both closed and open-ended questions. Thematic analysis of secondary data (student submitted records of learning from the learning circles) was also used. The results show that learning circles can provide students with an opportunity to discuss their practicum experience, a social and safe place to discuss their emotions, tensions or difficult situations; and can facilitate the co-creation of learnings with their peers. Two key success factors emerged for educators to consider. First, learning circles need to be incorporated as an intentional, in-class activity to support group sharing and learning becoming a social norm. Second, ‘just the right amount’ of facilitation is essential to support the group learning and reflection through initiating discussions and modelling reflective questioning, but also by drawing back when appropriate.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Getting the most out of work integrated learning (WIL) placements cannot rely on a single strategy. This chapter describes a two-pronged strategy trialled with final year public health and environmental health students transitioning to professional work. The first component acquaints students with the principles and practices required for effective transition, including self-efficacy, developing a professional identity and building resilience. The second, introduces learning circles as a means of fostering critical thinking (Hiebert, 1996) and peer learning. We argue that this combination of preparatory discussion and participation in regular learning circles prepares and supports students to gain the most from their placements. This chapter describes the theoretical underpinnings of this two-pronged approach, how it was implemented and the findings of its evaluation.

2 Supporting Resilience, Self-Efficacy and Professional Identity Building During Placements

Placement can be demanding and stressful for students. The first prong of our approach included preparatory discussions acquainting students with principles and practices to help students manage these demands and stressors. Three qualities are believed to be core: resilience, self-efficacy and a clear sense of professional identity (Bialocerkowsk, Cardwell, & Morrissey, 2017). Dornan, Boshuizen, King, and Scherpbier (2007) also recognise that a student ’s ability to participate in real world practice requires what they call ‘state of mind’ qualities, as well as practical competence (p. 84). Resilience refers to a student ’s ability to bounce back or recover from stress while on placement (Smith et al., 2008). Just as important as the ability to bounce back is the ability to move forward. Placement is an experiential opportunity with the potential to strengthen perceived self-efficacy and confidence. The term ‘self-efficacy’ was coined by psychologist Albert Bandura to describe a person’s beliefs in his or her ability to perform capably in a particular circumstance. Performance and functional accomplishment are key influencing factors on an individual’s perceived self-efficacy. According to Bandura’s (1986) Social Cognitive Theory, an individual’s cognitive processing of efficacy expectations can also be influenced by vicarious experience, verbal persuasion and emotional arousal. Self-efficacy is recognised as a measure of one’s capacity to cope with learning and performing, which can be applied to both a university and a workplace setting (Freudenberg, Cameron, & Brimble, 2010). Thomson, Bates, and Bates (2016) highlight that offering WIL is particularly important for students with low work self-efficacy so that they can ‘develop greater confidence in managing professional practice’ (p. 9). Finally, professional identity, that is identifying as a member of a professional group, positively contributes to transitioning to that profession. Accordingly, a delay in developing some level of professional identity can present a psychological barrier to transitioning from the role of a student to that of a professional (Crossley & Vivekananda-Schmidt, 2009).

This study confirms that while it is important to provide sessions aimed at preparing students for the stresses associated with transitioning to WIL placements, this is not sufficient. A second approach is required to give students the opportunity to engage cognitively at all levels of development. This is achieved using learning circles. This addition can not only support positive change in perceived self-efficacy but also reduce dysfunctional or defensive behaviours that may otherwise prevent learners from realising the full potential of the placement experience in relation to role transition.

2.1 Learning Circles

Learning circles emerged as a strategy to increase critical-thinking skills during practicums (Hiebert, 1996), and have been used for a variety of purposes, including strengthening change processes (Scriven, 1984); promoting a collaborative approach to professional development (Collins-Camargo, Sullivan, Murphy, & Atkins, 2015; Percy, Vialle, Naghdy, Montgomery, & Turcotte, 2001); and encouraging the development of learning organisations and learning communities (Cartmel, Macfarlane, Casley, & Smith, 2015). As a method used in various settings, learning circles have been described as both ‘a peer consultation model’ (Collins-Camargo et al., 2015, p. 33) and as a process of ‘guided conversations’ (Cartmel et al., 2015, p. 5). Learning circles involve facilitating reflective thinking processes within discussions. Cartmel et al. (Cartmel et al., 2015) detail the four reflective process steps required for practice: deconstruct (describe the situation from the learner’s perspective); confront (describe how they feel about the issue); theorise (share the sources of the ideas, linking to their study, research and others’ ideas); and think otherwise (describe how their thinking has changed and how they will act in the future). Participants are able to use the learning circles to ‘reflect on and share their insights, tensions and dilemmas’ and grow their understanding (Peters & Le Cornu, 2005, p. 1). The methodology provides both an opportunity to engage in co-construction of knowledge and a structure to help manage the emotional dimensions of being in a changing world or changed learning environment.

Learning circles have emerged recently as a strategy used by higher education degree programs to augment post-placement experiences. Pedagogically, learning circles provide a process to connect experiences with the communication skills required to develop shared meanings, critical thinking and professionalism (Grealish et al., 2017). Harrison, Molloy, Bearman, Newton, and Leech (2017) found that these group-based reflective activities not only facilitate the generation of shared and new knowledge but also have a positive influence on learning behaviour.

2.2 Theoretical Value of Learning Circles

Kolb and Kolb’s (2005) work contributes valuable insights into academic discourse about utilising learning circles in association with WIL placements as an opportunity for experiential learning. According to Experiential Learning Theory (ELT), learning is ‘the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience’, resulting from ‘the combination of grasping and transforming experience’ (Kolb, 1984, p. 38). WIL placements undertaken as part of higher education programs constitute significant experiential learning experiences. Accordingly, students should be able to demonstrate the reflective capacity to assimilate the concrete experiences gained during placement and transform them into thought and new ideas, conclusions and connections for future practice. Developing reflective capacity aligns with the call for higher education to emphasise deep learning, learning to learn how to achieve goals and to master content by engaging in critical thinking, problem solving, collaboration and self-directed learning (Johnson et al., 2016). Reflection is increasingly recognised as an important part of WIL strategies. Reflective practice supports students to develop their capacity to build cognitive bridges between classroom and placement learning in preparation for future work (Harvey et al., 2014; Wingrove & Turner, 2014). Building work-readiness requires learning not only in the cognitive but also in the affective domain, as emotional readiness is part of developing a true preparedness for work (Bandaranaik & Willison, 2015). Engaging with strategies informed by the ELT model might assist students to deal with and learn from the complexity of an experience and can contribute to development on several levels: affective, perceptual, and behavioural (Kolb & Kolb, 2005). However, while some students have a natural inclination to be reflective about their learning, a core element of ELT, many others will try to complete steps provided for formal reflective tasks without developing any deep meaningful level of reflective practice capability (Wong, 2016).

According to Kolb and Kolb (2005), creating ‘learning spaces’ offers a mechanism to foster deeper engagement with experiential learning and may engender more effective reflective practice (p. 208). Learning circles are an example of operationalising these learning spaces to support learning from the placement experience. Kolb and Kolb (2005) have also used Situated Learning Theory to extend our understanding of learning spaces beyond the physical context to include transactions between the person and the social environment. This builds on ELT and develops the idea of learning through socialisation and becoming part of a community of practice, which contributes to identity formation and a sense of transitioning towards a professional role. According to Kolb and Kolb (2005), principles for creating social learning spaces that enhance experiential learning include: respect for learners and their experience; using the learner’s experience of the subject matter as a starting point for learning; creating and holding a hospitable space for learning; and making space for conservational learning, for development of expertise, for acting and reflecting, for feeling and thinking, for ‘inside-out’ learning (motivated by learner’s interests), and for learners to take charge of their own learning. Thus, in theory, implementing learning circles based on these learning spaces and situated learning principles might augment the value of placements by using reflective and social processes to consolidate the individual’s placement-related learning.

For optimal impact, the learning circle may need to be operationalised at a time and in a space separate from the actual placement experience. Learning circles have been used to facilitate open discourse between students and staff in the placement environment and to develop an active learning community in the workplace, however, their impact in these settings is limited by the ability of staff and students to attend due to competing job commitments (Walker, Cooke, Henderson, & Creedy, 2013). In addition, trying to fit this activity into the actual work placement may be a drawback to the realisation of the ‘power of learning conversations’ as it doesn’t truly allow the ‘space’ or ‘time out’ needed to reflect and make sense of things (Le Cornu, 2004, p. 5). By necessity, the focus during placement is the concrete experience, the student ’s practice is their own responsibility and they are required to control ‘most of their problems independently by reviewing their own practice repeatedly’ (Khanam, 2015, p. 688). Augmenting the placement experience with an on-campus learning circle should support experiential learning and assist students to engage in adaptive and critical thinking to consolidate the experience as learning. Billet (2009) explains that a key role for university educators is to guide the student ’s critical thinking so that it is directed in productive ways, rather than leading to disillusionment related to confronting or uneasy experiences in workplaces.

A central requirement for realising effective integration of on-campus and off-campus learning is supporting students’ agency as active learners. This aligns with a key concept of the meta-cognitive experiential learning model of ‘a learning identity ’ (Kolb & Kolb, 2009a). It follows that, if students use the cyclical processes that ELT describes in the context of placement tasks, they will be able to recognise learning experiences, adjust their practice and deal with challenges. This, in turn, can be key to developing their resilience in the placement setting. Billet, Cain, and Le (2017) point out that engaging students in discussion about their authentic WIL experiences places them in a strong position to evaluate actively and learn from them. In order to make these meaningful connections, students need opportunities to feel that they have a ‘voice’ in constructing the learning narrative, which will in turn help them to take on and handle the difficulties of practice (Wong, 2016).

The learning space helps to facilitate and guide the cognitive monitoring and control of the learning occurring (Kolb & Kolb, 2009a). While students can distinguish between what has been learnt and what has been experienced, skilled facilitation is needed to help them ‘explore their ideas, to share and integrate their knowledge and insights about professionalism and to expand their emotions’ (Trede, 2012, p. 163). A conscious effort is required to challenge students to be active and agentic learners as, without support, many would simply attend and attempt to learn ‘by osmosis’ whilst in the WIL placement environment. The risk is, that without embedded opportunities for reflecting on practice experiences and drawing critical meaning from them, learners might develop poor standards and bad habits unintentionally. Providing a learning space and guiding the conversations, when needed, allows for social relations and discourse to raise awareness of, and question, standards, habits and even self-doubts.

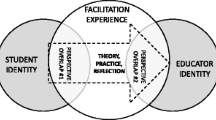

To support placement students’ engagement with experiential learning, the teacher may need to adapt their teaching style. Both pedagogy and andragogy exist within the scope of learning and teaching in higher education. Between pedagogy and andragogy the maturity of the learner is growing, and the style of learning moves from teacher-led to self-determined, with the learner taking on more control and responsibility (Blaschike, 2012; Halupa, 2015). Transformational learning occurs with the growth of learners’ autonomy and is driven by critical reflection and the development of self-knowledge (Halupe, 2015). Heutogogy is an expansion of the andragogy concept where the learning becomes more self-regulated (Blaschike, 2012). At the point of transitioning from undergraduate learning, the graduate should have the lifelong learning capabilities required for autonomous adaptation to workplaces and their evolving learning needs. Consequently, teaching that augments placement experiences needs to scaffold a style that is less structured, more learner-directed and more focussed on the learning process. The collaborative learning that learning circles seek to develop is a heutagogical course design element that can assist in the development of self-determined learning (Blaschike, 2012; Halupa, 2015).

2.3 Augmented Learning Activities in This Study

For this study, the two-pronged strategy described was introduced to augment the third-year undergraduate public health and environmental health WIL placement programs at Griffith University. The specific aims were to:

-

1.

Develop professional identity, self-efficacy, and resilience dialogue in placement preparation; and

-

2.

Increase student engagement in sharing learning from their placement experiences.

Students in these programs undertake placement during the second trimester (T2) of their final year. Twelve students were enrolled in one of these placements in 2017 and a further 19 undertook them in 2018.

In line with recommendations by Bialocerkowski, Cardwell, and Morrissey (2017), workshops that specifically addressed resilience, self-efficacy and professional identity were introduced prior to placement ‘as an inoculation’ to help learners to manage their placements (p. 67). Pre-placement sessions were modified to include more explicit discussion of professional identity, resilience, self-efficacy, stress and conflict management. Specifically, students were asked to label and discuss what professional identity was and share perceptions of what ideal professional qualities were. A session was also scheduled where a professional counsellor discussed approaches to developing resilience and managing stress and conflict whilst on placement .

Further augmentation of the placement experience in the classroom occurred through the introduction of five guided learning circles during tutorial times throughout the trimester. For each, the students were asked to prepare brief points on a placement experience to share with the group, such as something learnt, a challenge, a mistake, or how the unit with which they had been placed works. At the end of each learning circle students were asked to reflect on and document what they had learnt from the discursive experience and how they could put that learning into practice. The intervention was designed to strengthen student engagement in sharing and articulating the learning they identified as important to their practice and employability. Learning circles were also used to promote vicarious learning through students sharing their learning with others. Convenor-facilitated group discussions provided a mechanism for constructive feedback and a platform to reinforce students’ belief in being able to cope and handle new contexts and situations. This is what Bandura refers to as verbal persuasion (Bandura, 1977, p. 191).

The key focus of the study was to examine how students undertaking the placement course perceived the value of the deliberate educational strategies introduced (the pre-placement sessions and the learning circles), which were designed to enhance engagement in learning and support the development of identity , self-efficacy and resilience. A mixed methods approach was adopted, including several ways of collecting both quantitative and qualitative data.

-

1.

Survey instruments measuring the specific constructs of identity (utilised prior to the first intervention and at the end of the placement ); and self-efficacy and resilience (measured pre- and post-placement).

-

2.

Learning notes submitted by students in 2017 after at least three learning circles.

-

3.

A course experience survey administered in 2018, at the end of the placements, aimed specifically at gauging the perceived value of the learning circles.

Survey instruments consisted of a variety of questions measuring several key constructs. Questions to measure identity were based on an approach developed by Bialocerkowski, Cardwell, and Morrissey (2017) for their ‘Bouncing Forward’ post-placement workshops. This approach included asking a series of Likert-style questions that produced a score (administered pre- and post-placement ) as well as an activity that involved getting them to mark a point where they felt they were at on a 10 cm line representing a continuum between “student identity ” and “professional identity” and answering two open-ended questions about why they did not rate themselves higher or lower (undertaken pre-, during and post-placement ). Questions to measure self-efficacy came from Chen, Gully and Eden’s (2001) New General Self Efficacy Scale (GSE) and Subramaniam and Freudenbery’s (2007) task-specific self-efficacy items. Questions to measure resilience aligned with the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) developed by Smith et al. (2008). The study protocol had ethical approval from the Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol reference number 2017/142). In addition, open-ended questions in the survey instrument, as well as student learning notes, were analysed utilising thematically-oriented qualitative processes (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

2.4 Findings: Self-Perceptions of Identity

In both years, learners’ professional identity ratings improved following placement . With the single median scores derived from the Likert questions, this improvement was only marginal (Figs. 1 and 2). The “mark along a continuum” activity provided a finer grade of self-rating and valuable insights about their reasoning.

Interestingly, two students rated themselves lower midway through placement compared to pre-placement. This may reflect them questioning their professional identity when experiencing the real-life world of work, integrating learning, and comprehending the need for further development. By the end of their placement , all students believed they had moved forward from being a student towards being a professional. The growth in the 2017 cohort’s perceived professional identity ranged between 10% and 34%, with an average growth of 21%. These perceptions of professional identity are clearly subjective but do indicate that the final trimester in which these students completed their placement was an important period for their professional identity development. The findings support that the student ’s professional identity development, while not complete, was occurring during their higher education life phase.

The reasons provided by the students about why they would not rate themselves higher (professional identity) or lower (student identity ) provided further insights. Reasons related to the following: their extent of practical experience; progression through their degree (e.g. ‘enough studies to have somewhat of a thorough understanding’); perceived extent of learning; and confidence. These reflect key influences on participants’ reasoning and cognitive processing in forming a professional identity.

The dominant theme emerging across the three sample points was the importance of the amount of placement or experience the student had. Lacking sufficient or any previous placement experience appeared to influence students who did not rate themselves highly prior to enrolling in the placement course: ‘haven’t completed placement , haven’t put into action theory we have learnt, haven’t experienced “real world”’. At a point midway through their placement , the extent of placement or experience appeared still to be relevant and was reflected in comments like ‘I still have more experience to gain on practicum to better enhance my skills, therefore, I do not feel professionally competent in some areas’. However, by the end of their placement , there were more students referring to their placement experience as a determinant of why they rated their professional identity development more highly and why they felt able to demonstrate their capabilities: ‘throughout my placement I have been able to demonstrate and develop my skills and knowledge further’ and ‘because now after all my practicum I have more experience on what a [name of profession] does and I am capable to do some of these things’.

However, for some students, there was also a sense of anxiety about having had insufficient experience to rate themselves as ‘a professional’. For some public health students, this reflected their perception about the breadth of public health work: ‘I feel there are so many different aspects of being a public health professional and I have only experienced a little bit of that’. This suggests that there can be emotional (meta cognitive identity – I can do) barriers to be overcome when transitioning out of the higher education environment. This was also expressed by an environmental health student at the end of their program with the words ‘still feel like I need more work experience in order to consider myself an Environmental Health Officer’. A strong connection to a student identity may also hold students back, with some comments illustrating a struggle with letting go of their student role at the end of their studies: ‘I still feel that I am in that student phase where I still have more skills, knowledge and experience to gain’, or simply stated by a student as ‘student mind’.

It was typical for participants to perceive that the journey between being a student and becoming a professional required two essential and related elements: completing both the placement and the whole degree. Participants felt they could track the journey by the extent of completion of each: ‘Although I have not completed my studies I have gained some experience in the profession. I am on track to becoming a [name of profession]. Participants’ perceptions about the extent of their learning, and how much more there may be to learn, emerged as another theme: ‘I am still learning different things whilst on placement , so I feel I still have to develop some skills’. These comments reflect that part of engaging in WIL was seen to be testing, self-auditing and developing skills. This emphasises the importance of this time for dealing with the socio-emotional aspects of self-development and employability. However, at the end of their program there were still some comments that reflected self-perception of a need for more learning to rate themselves as being a professional. While some could have associated this with continuous improvement, for others the perception may represent a cognitive barrier to seeing themselves as closer to being a professional: ‘I still feel that I am in that student phase where I still have more skills, knowledge and experience to gain’.

Two potential barriers were evident: perceptions of the extent of learning and confidence. By the end of their program, the gaining of confidence influenced how high a participant rated their progress towards being a professional, and the gaining of confidence was typically associated with having undertaken placement: ‘Placement has helped me to transition into a more confident student /graduate , overall helping me to feel like an actual … professional’. A student ’s perception (or fear) of not having learnt enough (and not recognising their capacity for future learning and development to meet these needs) appeared to be a dysfunctional or defensive behaviour that blocked moving forward. This highlights a key role that augmented post placement activity can play: normalising emotions and encouraging engagement in developing self-efficacy and resilience.

Metacognition has played a role across the WIL experience for these students. At a subjective level, an individual’s learning on placement can be stifled by their metacognition (Kolb & Kolb, 2009b). Learning self-identity is a key concept in metacognitive models of experiential learning. Kolb and Kolb (2009b) explain that our self-identity is the sum of fixed and learning beliefs (I am a learner) and every time a student comes up against something that can trigger their assessment of an ability to learn, the self-identity is determined by the balance point of characteristics that reinforce a fixed self (e.g. negative self-talk, avoidance, or being threatened by others’ success) and characteristics of a learning self (e.g. trust in their ability to learn from experience, mistakes and others’ successes). Placement educators can encourage the tipping point towards the learning self if they incorporate learning activities that support embracing and trusting the experience, the learning process and redefining relationships with perceived failure.

2.5 Findings: Self-Efficacy and Resilience Ratings

The median General Self-Efficacy (GSE) score at the start of T2 for both cohorts in this study was 32. This median was maintained at the end of placements. While there was no significant growth in general self-efficacy it did indicate that the students were in a good position to start placement (Figs. 1 and 2).

Based on the self-efficacy items added to gain insights about specific measures of belief in ability to succeed in their chosen discipline, the starting median was 33 in 2017 and 33.5 in 2018 at the start of T2 and 35 in both years at the end of T2. Not only did the cohorts start with strong discipline-orientated self-efficacy, but they increased slightly in both years (Figs. 1 and 2).

At the start of T2 in 2017 the group resilience median on the BRS scale was in the normal range at 20 and increased by 2 points by the end of T2 (Figs. 1 and 2). Likewise, in 2018, the resilience median increased from 21.5 to 23 over the placement period. The students generally started with a normal level of ability to cope with difficulties and this did not increase significantly from the start to the end of the trimester.

2.6 Findings: Learning circles and the Types of Learning Occurring

The thematic analysis of the 2017 cohort’s learning circle notes revealed which types of learning and development the strategy appeared to assist the most. Students prepared both functional (how to) and dispositional (behaviour, thought and emotion) topics to discuss in the learning circles (see Table 1).

Many entries could be coded across several categories and subthemes. For example a student may have shared an aspect of a case and highlighted good practices, challenges or both. Many students wrote that they had prepared to share details or aspects of a case or project on which they were working. However, analysis of the notes students made on what was learnt from the Learning Circle revealed that no one focused on specific case details that someone else had shared. Instead, the dominant theme regarding perceived learning was that of good practices, followed by dealing with emotions and tensions and working on self-confidence. These all fall into the category of dispositional learning. Interestingly, while not many students wrote about presenting a tension or challenge, they were experiencing or had observed for discussion, how to deal with tensions was one of the dominant themes in both the responses for ‘what was learnt’ and ‘what learning could be taken away and applied’.

The types of difficult situations or emotional tensions shared included: observing or personally dealing with client aggression (e.g. ‘I learnt interpersonal skills remaining professional even when they were emotive’); frustrations over jurisdiction (e.g. ‘it is challenging most you can do is …’); conflicting with personal values (e.g. ‘feelings while imposing enforcement of legislation’); dealing with work day stresses (e.g. ‘fatigue’); self-confidence (e.g. ‘self confidence in interactions’) and not knowing how to voice concerns with supervisors (e.g. ‘not knowing how to speak up about my frustrations’).

It was clear that exposing challenges, frustrations, emotions and difficulties is easier for some than others, however, being exposed and part of a discussion about them has learning, self-efficacy and resilience benefits for both the individual who brings the challenge to the learning circle and those who become part of the ensuing discussion. For example, when an environmental health student raised frustrations about the confinement of jurisdiction, another student acknowledged in their notes that, as part of a ‘helping profession’, it can be hard not to be able to respond when a concern is not in their jurisdiction and discussed what actions they could take if they came up against this type of situation. This created new learning that appears likely to help participants with self-efficacy if confronted by the particular ‘tension’ in future work: ‘Ability to be the middle man between the community and other government organisations’. Future action that students felt they could apply from this learning included: ‘even though an issue might not be under my jurisdiction I can still go speak to the community members to put them at ease whilst also helping the other organisation’; and ‘reassure customers and collect data to then pass on to the relevant authority’. This demonstrated that the learning circle process has been able to support students to share experiences, reflect upon them and to create new understanding with or from their peers’ experiences. Our findings also suggest that agentic self-directed learning capabilities can be supported by encouraging students to reflect on and share their experiences. They emphasise how important it is to allow the inclusion of contentious experiences and how they were reconciled, allowing the students to develop meanings from their experiences and judgements about how to deal with challenging situations (Billet, 2009; Nagarajan & McAllister, 2015). Facilitating peer learning through sharing, questioning and resolving tensions emerges as an important aspect of integrating work-based learning supported by learning circles.

Resilience building was also evident. For example, when an environmental health student expressed that they were struggling with not being permitted to be part of a confidential investigation or to view confidential information and that they were taking it personally and were frustrated about being blocked from essential learning, the student writings demonstrated the value the learning circle provided for working through these emotions. Several students noted aspects of this discussion as a key learning including learning about ‘confidentiality in investigation processes’. If they were to come up against the same type of situation in the future, they had learnt to avoid dysfunctional thinking that might disrupt moving forward during placement : ‘when EHOs don’t want to share confidential information, which is part of an investigation, we cannot take it personally and [need to] understand the reason why’.

2.7 Findings: Learning Circles from the Student Perspective

The 2018 cohort was asked whether learning circles had added value to their placement experience. Of the 68% who answered, all agreed or strongly agreed that it had. When asked what was good about learning circles, student responses indicated that they appreciated the opportunities to share experiences (e.g. ‘share knowledge and learnings and discuss as a group why certain approaches are taken’); to hear and learn from others’ experiences (e.g. ‘sharing information is so valuable because I can apply techniques to situations that may arise’); and one student raised being able to practice having a ‘voice’ in terms of ‘good practice for students to [become] used to participating/have their say’. The learning circle process used was connected to: feelings of accomplishment from being able to contribute (e.g. ‘nice to talk about what we’ve learnt and feel accomplished – nice to discuss it among peers who know what we’re talking about’); reduced stress from knowing that others were having the same issues and had found learning strategies to deal with them (e.g. ‘It was good to talk to everyone and see how they were coping … normally I thought I would be the only one feeling confused or stressed, but after the group talks I felt more relaxed and calm’); and gaining deeper insights from questions raised, reflection , and feedback (e.g. ‘it’s good to share experiences to relate to other students on prac … it helps to talk about issues or barriers during prac and discuss feedback and advice’).

In 2018, students were also asked if they felt there were any drawbacks from being involved in the learning circle process. Their responses indicated that they believed the main drawback was time requirements and competing demands, including placement activities. Some also made comments suggesting that they were challenged by finding a specific learning to contribute and felt more confident in value-adding to the discussions of other students (e.g. ‘sometimes it was difficult to come up with a key learning to contribute … you could have a discussion about other people’s learnings’). Another said that they ‘would like to combine the sections covering “what did you learn” and “how could you put into practice” stating that those “sections tend to link together/don’t double up on notes’. This suggests that they were not comfortable separating the learning itself from how they could apply it in the future. This demonstrates the importance of encouraging students to separate and distinguish between analysis (conceptualisation) and use (utilisation) as they represent two different and important aspects of the reflective and recursive learning cycle.

2.8 Implications for the Educator

While students may rate themselves as resilient, we believe that it is warranted to have learning activities that support this resilience at times when they may be tested by difficulties on placement . Learning circles provide an important learning space. In the context of the metacognitive models of ELT (Kolb & Kolb, 2009b), learning circles could be seen as a space nested within social systems. As such they create a social environment that can influence the learner’s experience. These learning spaces support the ‘experiential learning process’ and the generation of new knowledge by supporting conscious resolutions of the dual dialectics of action/reflection and experience/abstraction (Kolb & Kolb, 2005, p. 194). The concrete experience of placement provides the platform for observations and reflections. Reflections can then be assimilated and distilled into abstract concepts in the learning space, from which new implications can be drawn. The learning circles demonstrated that conversational learning strengthened reflection and conceptualisation. The learning phases of the learning circle include the student having a concrete experience on placement , thinking about it, sharing it with the learning circle, and finally, the ensuing dialogue leading to collective interpretation and the development of shared meaning that can be used to construct future action. The group conversation about placement in our learning circles stimulated reflection and deeper interpretive learning.

Active reflection is believed to deepen learning from experience. Consequently, reflecting on actions and practice should be integrated into placement learning activities. This may require helping learners to work through feelings and emotions as ‘negative emotions such as fear and anxiety can block learning’ (Kolb & Kolb, 2005, p. 208). This reflects what Kolb and Kolb (2005) term ‘making spaces for feeling and thinking’ in their principles for the promotion of experiential learning in education (p. 208). Also, making the learning spaces places where students can take control and responsibility for their learning is believed to enhance their ability to learn from experience (p. 209). Accordingly, it is important to involve them in the process of constructing their view and knowledge and to promote the development of the meta-cognitive skills used in active learning and the capacity for self-direction. This not only empowers students to take responsibility but also supports the development of skills to learn from uncomfortable experiences, in a way that connects to Boler’s (1999) work on the pedagogy of discomfort. As demonstrated, peer group discussion can provide opportunities to create new ideas on how to deal with and learn from difficult situations. Students will be more empowered by this type of learning than if the placement convenor directed them on how they should deal with something and prescribed what they believe the relevant learning to be. Kolb and Kolb (2005, p. 209) label this principle ‘making space for learners to take charge of their learning’.

Allowing for the narrative to play out is important and separates learning circles as a meaningful mechanism for reflection . Wong (2016, p. 7) points out that the narrative becomes a way ‘for practicum students to translate knowing into telling’. Discussion in the classroom is considered important to integrating the work experience to the learning space. As in this study, Wong identifies that the crises that students experience on placement often involve ‘confidence, self-doubt, identity , and everyday difficulties encountered during practicum ’. These crises provide opportunities to make meaning from experience and reflection .

At an heutagogical level, the classroom starts to become a community of practice. For teaching to augment learning from placement effectively, it needs to be well facilitated, to foster trust amongst the teacher and the learners, and to create a safe learning space in which students can share their narratives. This aligns with another of Kolb and Kolb’s (2005, p. 207) principles for the promotion of experiential learning in education: ‘respect for learners and their experience’, described as ‘the learners feel they are members of a learning community who are known and respected by faculty and colleagues and whose experience is taken seriously’. The facilitator has a role in building this into the process and keeping the other end of the continuum (alienation, aloneness, feeling unrecognized and devalued) at bay.

Learning circles can be mechanisms to create social learning spaces. When integrating placement into curriculum, educators can promote the capacity for developmental learning by acknowledging that learning spaces are not defined by the concrete experience alone, but also by social learning and the ability to make connections between the two. Interestingly a student in this study recognised that learning circles allowed students to practice participating and to have a voice. This active practising of being part of problem identification, solution formation and having a voice is an aspect that Wong (2016) has argued assists in developing skills to handle difficulties in the workplace. So, how do we create a space in which students feel they can participate and have a voice? A hospitable learning space for conversational learning relates to creating space where the learner feels psychologically safe and supported to face challenges and learn from expressing and confronting differences experienced between personal practice and expectations, between ideas, beliefs and values that can lead to new understandings. Creating space for conversational learning is recognised as a mechanism for providing opportunities for reflection and making meaning about experiences and thus improving the effectiveness of learning related to placement (Kolb & Kolb, 2005). However, this can be dependent on creating psychologically safe conditions and the integration of ‘thinking and feeling, talking and listening, leadership and solidarity, recognition of individuality and relatedness, and discursive and recursive processes’ (Kolb & Kolb, 2005, p. 208).

Our findings suggest that just the right amount of facilitation is essential. This supports the group learning and reflection through initiating discussions and modelling reflective questioning. Drawing back the facilitation when appropriate is also critical to allow students to take control and develop organically the reflective and group skills that will stand them in good stead to handle difficulties in the workplace, un-facilitated, into the future.

Another key finding was that learning circles need to be incorporated as an intentional, in-class activity to support group sharing and learning becoming a social norm. Students mentioned competing demands for their time as a drawback. The small allocation of marks given to the task and the provision of some flexibility by not making it a requirement to attend all the learning circles supported the buy-in that did occur. Students also appreciated that they were fortnightly rather than weekly (e.g. ‘a great experience and having them every two weeks was good’). It is questionable whether students would have attended the initial learning circles if there were no marks allocated, not only due to the competing demands but also to uncertainty about the process. However, from our observations, and evidence from student comments on the value of the learning circles, it is clear that students became more confident in the process after participating and wanted to be part of the evolving discussions and learnings. Some voluntarily attended more than the required number of learning circles. When previous cohorts were asked if they wanted to share and discuss aspects of their placement experiences with the class they had been less willing to. Learning circles have made this a named and accepted practice.

The success of the strategy is reliant on buy-in on the part of the student. Hiebert (1996) asserts that it is the story telling that provides the mechanism for sharing knowledge and supporting socialisation. Koenig and Zorn (2004) expands that story telling is a teaching and learning approach that develops from the lived experience of the student , helps them explore personal roles and make sense of the lived experience and is an approach that helps a diverse range of undergraduates with various learning styles. Le Cornu (2004) points out that in a learning circle the conversation is not an ordinary conversation or exchange as it should go beyond describing to making meaning or deeper understanding, to be a ‘learning conversation’ (p. 7). While the facilitator can help provide a structure and environment for this, individuals need to be willing to learn ‘from and with others’ and to contribute to the learnings of others (p. 7). Le Cornu argues that the ‘locus of control in the learning process remains with each person’ (2004, p. 7) and probably the most powerful aspect of conversational learning may be lost if students do not take it on and develop responsibility for the learning (Le Cornu, 2004, p. 7). In recognising that the principle of making space for conversational learning (Kolb & Kolb, 2005) is important to making experiential learning meaningful, it is also important to note there are underlying social dimensions that need to be developed, such as group acceptance and participation. In this study, the facilitator observed this growth and the learning circle process became a valued and social norm over the trimester, but we are also aware that it can be limited by the motivations of those involved.

A limitation of the study was its size. The sample sizes were small and did not support statistical analysis of the measured constructs. The strength of this research emerged through the subjective accounts, which provided insights into self-perceptions of professional identity, resilience and self-efficacy in the placement context, as well as the usefulness of learning circles as perceived by students. It is also worth noting that the learning circles typically involved six – 12 participants in size, which supported the conversational style. However, where resource-limitations necessitate larger groups, involving everyone and timing would become more difficult.

3 Conclusion

Helping students get the most out of their work integrated placements has been enhanced by the two-pronged strategy trialled: preparatory discussions acquainting students with principles and practices required for transitions to professional work, namely self-efficacy, building resilience and developing a professional identity; and regular learning circles. Learning circles offer a learning strategy that augments placement with conversational learning. A critical success factor is design and just the right amount of appropriate facilitation, which reduces over time. They are successful when they reflect Kolb and Kolb’s (2009a) principles for promoting experiential learning, namely respect for the learner and the experience; creating a hospitable space for learning; and making space for conversational learning; acting and reflecting; feeling and thinking, as well as learners taking charge of their learning. This requires conscious and deliberate facilitation: leading when needed and drawing back a little when cohesive and supportive social norms develop. However, at the time when students are transitioning from traditional learning and have many competing demands, we believe that, without making this a required activity with marks being allocated, many students would not readily take up this learning opportunity. Students’ self-identity often wavers during placement , with real life work triggering uncertainty over whether they have the skills to succeed. Preparatory discussions and learning circles offer a way to engage in dialogue and allow co-creation of new and deeper learning, which supports meta-cognitive development (I can do this), overcoming personal blockages and moving forward with responsive goals and actions.

References

Bandaranaike, S., & Willison, J. (2015). Building capacity for work-readiness: Bridging the cognitive and affective domains. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 16(3), 223–233.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bialocerkowsk, A., Cardwell, L., & Morrissey, S. (2017, February). Bouncing Forward: A clinical debriefing workshop in professional identity, self-efficacy, and resilience in Master of Speech Pathology students. In S. Billett, M. Cain & A. Hai Le (Eds)., Augmenting students’ learning through post-practicum educational processes: Development conference handbook. Paper presented at Augmenting students’ learning through post-practicum educational processes: Development Conference, Griffith University, Gold Coast, Australia.

Billett, S. (2009). Realising the educational worth of integrating work experiences in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 34(7), 827–843.

Billett, S., Cain, M., & Le, A. (2017). Augmenting higher education students’ work experiences: Preferred purposes and processes. Studies in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1250073

Blaschke, L. (2012). Heutagogy and lifelong learning: A review of heutagogical practice and self-determined learning. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 13(1), 56–71. Athabasca University Press.

Boler, M. (1999). Feeling power: Emotions and education. New York, NY: Routledge.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Cartmel, J., Macfarlane, K., Casley, D. M., & Smith, K. (2015). Leading learning circles for educators engaged in study. Canberra, Australia: Department of Education and Training.

Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organizational Research Methods, 4(1), 62–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810141004

Collins-Camargo, C., Sullivan, D., Murphy, A., & Atkins, C. (2015). A collaborative approach to professional development: A systems change initiative using interagency LearningCircles. Professional Development: The International Journal of Continuing Social Work Education, 18(2), 32–46.

Crossley, J., & Vivekananda-Schmidt, P. (2009). The development and evaluation of a professional self identity questionnaire to measure evolving professional self-identity in health and social care students. Medical Teacher, 31(12), e603–e607. https://doi.org/10.3109/01421590903193547

Dornan, T., Boshuizen, H., King, N., & Scherpbier, A. (2007). Experience-based learning: A model linking the processes and outcomes of medical students’ workplace learning. Medical Education, 41, 84–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02652.x

Freudenberg, B., Cameron, C., & Brimble, M. (2010). The importance of self: Developing Students’ self efficacy through work integrated learning. International Journal of Learning, 17, 479–496. https://doi.org/10.18848/1447-9494/CGP/v17i10/58816

Grealish, L., Armit, L., van de Mortel, T., Billett, S., Shaw, J., Frommelt, V., Mitchell, C., & Mitchell, M. (2017, February). Learning Circles to develop inter-subjectivity. In S. Billett, M. Cain & A. Hai Le (Eds), Augmenting students’ learning through post-practicum educational processes: Development conference handbook. Paper presented at Augmenting students’ learning through post-practicum educational processes: Development Conference, Griffith University, Gold Coast, Australia.

Halupa, C. (2015). Pedagogy, andragogy, and heutagogy. In Halupa (Ed) Transformative curriculum design in health sciences education (pp. 143–158). IGI Global Publishers. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-8571-0.ch005

Harrison, J., Molloy, E., Bearman, M., Newton, J., & Leech, M. (2017, February). Learning from practice…vicariously: Learning Circles for final year medical students on clinical placement. In S. Billett, M. Cain & A. Hai Le (Eds), Augmenting students’ learning through post-practicum educational processes: Development conference handbook. Paper presented at Augmenting students’ learning through post-practicum educational processes: Development Conference, Griffith University, Gold Coast, Australia.

Harvey, M., Baker, M., Fredericks, V., Lloyd, K., McLachlan, K., Semple, A.-L., & Walkerden, G. (2014). ACEN 2014: Conference proceedings of the 2014 Australian Collaborative Education Network National Conference: Work integrated learning: Building capacity (pp. 167–171). Springvale, VIC: Australian Collaborative Education Network (ACEN).

Hiebert, J. (1996). Learning circles: A strategy for clinical practicum. Nurse Educator, 21(3), 37–42.

Johnson, L., Adams Becker, S., Cummins, M., Estrada, V., Freeman, A., & Hall, C. (2016). NMC horizon report: 2016 higher education edition. Austin, TX: The New Media Consortium.

Khanam, A. (2015). A practicum solution through reflection: An iterative approach. Reflective Practice, International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 16(5), 677–687.

Koenig, J. M., & Zorn, C. R. (2004). Using storytelling as an approach to teaching and learning with diverse students. Journal of Nursing Education, 41(9), 393–399.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Kolb, A., & Kolb, D. (2005). Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing experiential learning in higher education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4(2), 193–212.

Kolb, A., & Kolb, D. (2009a). Experiential theory: A dynamic, holistic approach to management learning, education and development. In S. J. Armstrong & C. Fukami (Eds.), Handbook of management learning, education and development (pp. 42–68). London,UK: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857021038.n3

Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2009b). The learning way: Meta-cognitive aspects of experiential learning. Simulation & Gaming, 40(3), 297–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878108325713

Le Cornu, R. (2004) Learning circles: Providing spaces for renewal of both teachers and teacher educators. Refereed paper presented at the Australian Teacher Education conference, 7–10th July, Bathurst. http://www.atea.edu.au/ConfPapers/2004%20-%20ISBN_%20%5B0-9752324-1-X%5D/ATEA2004.pdf#page=151

Nagarajan, S., & McAllister, L. (2015). Integration of practice experiences into the Allied Health Curriculum: Curriculum and pedagogic considerations before, during and after work-integrated learning experiences. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 16(4), 279–290.

Percy, A., Vialle, W., Naghdy, F., Montgomery, D., & Turcotte, G. (2001). Enhancing engineering courses through quality teaching and learning circles. In Proceedings of the Australian Association for Engineering Education 12th annual conference (pp. 391–396). Brisbane, QLD: QUT.

Peters, J. & Le Cornu, R. (2005). Beyond communities of practice: Learning circles for transformational school leadership, Chapter 6. In P. Carden & T. Stehlik (eds) Beyond communities of practice, Queensland, Post Pressed.

Scriven, R. (1984). Learning circles. Journal of European Industrial Training, 8, 17–20.

Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972

Subramaniam, N., & Freudenbery, B. (2007). Preparing accounting students for success in the professional environment: Enhancing self-efficacy through a work integrated learning program. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 8(1), 77–92.

Thompson, C., Bates, L., & Bates, M. (2016). Are students who do not participate in work-integrated learning (WIL) disadvantaged? Differences in work self-efficacy between WIL and non-WIL students. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 17(1), 9–20.

Trede, F. (2012). Role of work-integrated learning in developing professionalism and professional identity. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 13(3), 159–167.

Walker, R., Cooke, M., Henderson, A., & Creedy, D. (2013). Using a critical reflection process to create an effective learning community in the workplace. Nurse Education Today, 33(5), 504–511.

Wingrove, D., Turner, M. (2014). Integrating learning and work: Using a critical reflective approach to enhance learning and teaching capacity In Proceedings of the 2014 Australian Collaborative Education Network, ACEN national conference, Gold Coast, Australia, 1–3 October 2014.

Wong, A. C. (2016). Considering reflection from the student perspective in higher education. SAGE Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016638706

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Murray, Z., Roiko, A., Sebar, B., Rogers, G.D. (2020). Fostering Peer learning and Self-Reflection: A Two-Pronged Strategy to Augment the Effectiveness of Work Integrated Learning Placements. In: Billett, S., Orrell, J., Jackson, D., Valencia-Forrester, F. (eds) Enriching Higher Education Students' Learning through Post-work Placement Interventions. Professional and Practice-based Learning, vol 28. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48062-2_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48062-2_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-48061-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-48062-2

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)