Abstract

Career advancement and financial success for female physicians entail navigating gender norms (real and perceived) in a still male-dominated profession. The evidence demonstrates that female physicians are able to perform at the level of their male counterparts and that gender diversity increases the value and performance of organizations, yet women have not yet achieved the same level of opportunity and reward. In this chapter we will explore the success gaps, that which contributes to the gaps, and what men and women can do to close the gaps to ensure the freedom and opportunity to pursue personal and professional success.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Leadership

- Academic advancement

- Finances

- Debt

- Pay Gap

- Promotion

- Negotiation

- Confidence

- Communication

- Tokenism

Exemplary of a champion, NIH director Dr. Collins wrote…

“I want to send a clear message of concern: It is time to end the tradition in science of all-male speaking panels,”…. “Starting now,” he added, “when I consider speaking invitations, I will expect a level playing field, where scientists of all backgrounds are evaluated fairly for speaking opportunities. If that attention to inclusiveness is not evident in the agenda, I will decline to take part. I challenge other scientific leaders across the biomedical enterprise to do the same.” [1]

New York Times June 12, 2019

In 2019, the World Health Organization published “Delivered by Women, Led by Men: A Gender and Equity Analysis of the Global Health and Social Workforce.” The authors reported that 70% of the global health-care workforce is female. Labor was segregated by gender norms, horizontally (across specialties) and vertically (through leadership). The gender pay gap in healthcare was higher than in any other sector of the economy. Female professionals were clustered into “low-status/less paid” roles. There was a lack of gender parity in leadership driven by “stereotypes, discrimination, power imbalance, and privilege,” and that this disadvantage can be multiplied by other factors such as race, class, etc. The authors reported that bias, discrimination, and harassment were associated with attrition, low morale, and ill health. Whereas empowering women with education, financial well-being, and autonomy generally improves the well-being of her family, community, and society at large, and female leaders commonly improve health for all [2].

Men and women in medicine are held accountable to the same rigorous strictly enforced standards for entering and graduating from an accredited medical school, passing national licensing exams, completing approved residency training, achieving board certification, maintenance of certification, and credentialing and complying with the oversight of medical staff. Women pay the same tuition, make the expected personal sacrifices, and are as capable as their male colleagues. Since half of the medical graduates are female, it follows that we would want female physicians working at full capacity. Yet currently female physicians do not achieve the same level of success (professional rank or reward).

In 2017, the number of women entering medical school surpassed men (50.7%) [3]. However, in this chapter we will demonstrate that without a substantive change in the culture of medicine, the likelihood a woman entering medical school in 2017 will become chief medical officer, dean, department chair, full professor, editor in chief, RO1 grant recipient, first or last author on a manuscript, invited editorialist, or a specialist in the most lucrative specialties is significantly less than that of her male counterparts. It is less likely that she will marry or have children, and if she does, it is more likely she will carry more domestic responsibilities related to the care of the household and children. These discrepancies in her success, defined as personal and professional rank and rewards, cannot be completely explained by specialty, practice setting, work hours, productivity, race, ethnicity, year in academia, marital status, and parental status.

In this chapter we explore the gender gap in career success, explore some of the theories offered in the literature that underlie the gap and may explain a proportion of the phenomenon, and finally seek potential strategies and tactics to close the gap.

The Success Gap

Pay Gap

Female physicians have been reported to earn less than their male colleagues.

Female physicians are reported to earn from 64% to 90% that of male physicians [4,5,6,7,8]. Women in other fields generally earn 80–82% of what men are paid for similar work [9]. These pay gaps start with the first job after training and persist over a women’s career [10, 11] and can be especially problematic at the intersection of gender and race with Black, Native American, and Latino women making 52–58% of their male colleagues [9]. From the start of her career, at the time of this writing, female physicians earn an unadjusted average of $20,000 less in annual compensation than male counterparts [7, 8, 10, 12, 13]. Per these authors, this pay gap was not attributable to her specialty, practice setting, work hours, productivity, race, ethnicity, year in academia, marital status, or parental status. However, after adjusting for working part-time and taking leave, the pay gap shrunk to approximately $17,000 and did not reach statistical significance [7]. Part-time physicians reported lower compensation and fewer opportunities to advance, which in turn lowered career satisfaction [7, 14]. Women are more likely to work part-time.

Female physicians seem to be segregated into specialties with lower status and compensation. The gender pay gap was seen across 446 major US occupations examined by the Wall Street Journal; they found women earned less than men in 439 of these occupations, and this gap was magnified in some of the highest-paying occupations, specifically doctors and surgeons, financial specialists, and lawyers and judges [4]. In medicine, Desai et al. examined 13 medical specialties and found that the more lucrative the specialty, the more likely it was dominated by male physicians even after adjusting for hours, productivity, and years of experience [12]. Specialists stand to earn two to three times the salary of general medical doctors [15]. In 2012, cardiology was the medical specialty with the lowest percentage of women at 10.7% [12]. Whereas, general primary care was 49% female in 1999 and dropped to 33% by 2008 [10], which suggests evidence of diversification. Perhaps more importantly, female patients may benefit from having more female specialists. For example, cardiologist Dr. Donna Arnett advocates for more female cardiologists since heart attacks are the leading cause of death in women, and their presenting symptoms are currently described as “atypical” compared to those seen in men [16].

Leadership Gap

Women are less likely to be recognized as leaders.

It has been reported that in the United States, approximately 95–98% of chief executive officers of Fortune 500 and S&P companies are men [17]. Both men and women have an implicit bias that leaders are men; perhaps the fact that men are in leadership positions serves as a confirmation bias to reinforce that perception [18]. In healthcare, approximately 3–18% of chief executive officers and chief medical officers, 6–16% of deans, 13–15% of department chairs, 9% of division chiefs, and 19% of full professors are female [19,20,21,22]. This is in spite of the fact that 70–80% of the health-care workforce, 50% of medical school classes, and 34–40% of the practicing physicians are female [21,22,23].

Women can be exceptional leaders, but face confirmation bias

Women can be exceptional leaders, but seem to face some bias. Zenger et al., in one study published in Harvard Business Review, found that women were perceived as or more effective than men in 17 of 19 leadership competencies and were exceptional at taking initiative, practicing self-development, and driving for results and displaying honesty and integrity (men scored higher on strategic perspective and technical/professional expertise) [17]. In a different study, it was found that strategic roles are more often assigned to men, whereas operational roles are more often assigned to women, which can convey a bias that women have less aptitude for strategy and their absence in these roles serving as a confirmation bias [24]. Zenger et al. also evaluated how 40,184 men and 22,600 women assessed their own leadership effectiveness and found that women underestimated their abilities and men overestimated them [17]. Perception is not always reality, which suggests that men and women would both make better decisions if more aware of inherent bias in themselves and others.

Gender diversity in leadership improves organizational performanc

Gender diversity in leadership improves organizational performance. Valerio et al. reported that after they sorted companies into quartiles based on their proportion of women on the board, the companies in the top quartile of female inclusion outperformed those in the bottom quartile by 15% for sales, customers, and profits [25]. Turban et al. examined 1069 companies in 35 countries over 24 industries and found that a 10% increase in Blau’s index (a diversity index taking into account the ratio of men to women) increased the market value to 7% when coupled with the belief that gender diversity was important and “normatively” accepted (publicly declared and actively pursued in earnest) [26]. Furthermore, 67% job seekers look for diversity in the workforce, and 61% of female candidates look for gender diversity in the leadership team and opt to join a firm with diversity in the leadership team [26].

Clinical Care Recognition Gap

Female physicians were less likely than male physicians to be recognized as physicians by patients (78.5% vs. 93.3%, in one study of ER physicians) [27]. Yet female physicians perform as well as their male counterparts. In an analysis of 1.5 million Medicare patients treated by female versus male physicians, the patients treated by female physicians had a statistically significant lower 30-day mortality rate (15.02% versus 15.57%) and a lower hospital readmission rate (11.07% versus 11.49%) [28]. Female physicians have been shown to be more likely to spend more time with patients and engage in shared decision-making, counsel patients, tend to their psychological needs, attend to preventative services, and achieve better outcomes with less litigation [29, 30].

Academic Success Gap

Female physicians are less likely to be introduced by professional title when presenting at major meetings and are less likely to be invited to give these important presentations [31, 32]. In spite of being as equally committed to academic medicine as male counterparts and comprising 40% of the academic faculty at the time of this writing, female faculty make up only a quarter of tenured faculty [7]. Women advance to full professor more slowly and are less likely to make full professor with a ratio of female to male full professors of 1:4 [16, 21, 23, 33, 34]. Furthermore, a 2016 study of 10,241 academic physicians from 24 public medical schools reported that female full professor salaries were comparable to male associate professors and female associate professors salaries were comparable to male assistant professors [35]. Despite adjustments for potential confounders including age, years of experience, faculty rank, specialty, scientific authorship, NIH funding, clinical trial participation, and Medicare reimbursement, nearly 40% of the differences in salaries between men and women remained unexplained. In academia, if one does not advance to full professor, it can account for a $60,000 annual pay gap [7]. These financial inequities compound over decades.

Academic institutions have been reported to give less generous start-up packages to women than men, reporting a difference of $585K versus $980K, respectively [36]. In another study, Bates et al. reported a similar disparity of $400 K for junior facility doing basic research [36]. Compared to men, the women are less likely to transition from a K Award to an established RO1 within 5 years, 19% versus 25% [34]. Women seem less likely to apply for RO1 grants, compared to men, 27% to 73%, respectively. In published work in the medical journals, women account for a third of the first authors, 4–19% of senior authors, 11–19% of invited guest editorials in the prestigious journals NEJM and JAMA, and account for 7% of the editors in chief [34]. The slowdown during the critical early years in a woman’s career has been often been referred to as “the motherhood tax,” “the maternal wall”, which will be discussed below.

Family and Citizenship Gap

Female physicians are less likely to marry (79% versus 89%) or have children (81% versus 92%) [7]. Half of female physicians are married to another physician (42–50%), whereas, a less than a third of male physicians are married to another physician (15–30%) [37]. Compared to their male colleagues, women are less likely to have a partner who works less than full-time outside of the home (85.6% versus 44.9%) [38], and it is not clear what proportion of these female physicians are the primary bread winner for their families. Women are more likely than men to work part-time or to take an extended leave (22% versus 15%). Female physicians are more likely to be the one who is primarily responsible for domestic duties, including care of the children and elderly. On average, female physicians with children were found to perform 10 hours less professional work per week than those without children, and female physicians perform 100 more minutes per day or 8.5 more hours per week on domestic work (caring for children and running the household) than male physicians [38, 39]. In addition to a disproportionate share of household and family responsibilities at home, many women also report discrimination at work for having these responsibilities. In one survey of 5782 female physicians, 66.3% reported gender discrimination at work, and 35.8% felt discriminated against for issues related to motherhood. Of those who experienced maternal discrimination, 89.6% reported discrimination against pregnancy and taking maternity leave [40]. Female physicians felt judged as “lazy” professionals if working part-time and judged as a bad mother if working full-time [22, 40]. For men, the family is considered a support system. For the women, the family is considered an additional responsibility. This shift for women to cut down on professional work to take on more domestic work is coined the “motherhood penalty” and the “fatherhood bonus” [8]. This is not to say that men would not also prefer to have equal time bonding with and raising their children.

Exploring the Gap

The segregation of women in medicine into low-status, low-earning areas horizontally (across specialties) and vertically (in the hierarchy) raises the question of whether women self-sort as a reflection of women’s preferences toward “caregiving” traits, or whether they are marginalized by a male-dominated profession [41]. Riska et al. offer several models to consider. Perhaps women are socialized into gender norms based on a “deficient focus” (lacking traits as a gender needed to advance within the profession), or “asset focus” (possessing traits, for example, suited to compassionate care for children and the elderly). Or, perhaps the status of the male-dominated profession must be defended by subjugating or excluding women. Another possibility is viewing the medical profession as what Riska calls “discourse and relational,” and thus discursive strategies are used by the male-dominant in-group to create cultural practices that define women’s roles (e.g., women’s health specialty) [41]. The dominant group might also claim a lack of qualified candidates to explain the underrepresentation of women – the “meritocracy myth” [42,43,44]. However, the female may not be deemed as qualified because she has not had the opportunity, through position and promotion, to demonstrate her qualifications; this privilege might be considered an “asset” that the nondominant group members do not possess [45, 46]. Compared to a member of the dominant in-group, the nondominant group member may have to work much harder to “merit” the opportunity. For example, as reported in the review by Kang et al., women had to be 2–5 times more productive than men to be hired for similar postdoctoral positions [47]. Those that succeed lead in shaping the future of medicine.

Perhaps, men and women have a different notion of success.

One hypothesis for the gender gap is that men and women define success differently and pursue it accordingly. One study of physicians asserted that men define success as achieving goals and social recognition through income and promotion, whereas, many women define success by their social relationships, “personal challenges,” and the desire to be more “autonomous and less dependent on external recognition.” These authors defined objective career success as titles, publications, and organizational metrics and subjective career success as satisfaction and self-efficacy in teaching, research, and clinical work. The authors found a gender gap in objective career success, but not in subjective career success. These findings seem to conform to gender norms, and the conclusion drew criticism for not accounting for the social constructs that could have produced the results such that they may not be reflective of women’s preferences [48]. Others have speculated that due to estrogen women may be more emotionally attuned, nurturing, and relational, whereas men, due to testosterone, may be more competitive, risk-takers, aggressive, and more independent-minded. It remains unknown to what extent female and male physicians self-sort into their preferred roles versus are expected to maintain the norms of the dominant culture.

Women will self-silience themselves for fear of losing critical relationships.

A 2019 review on “self-silencing and women’s health” explains the phenomenon [49]. More than men, perhaps due to a combination of gender norms, lower social status, and biologic sex, women have been more dependent on and gain power through relationships and communication. As such, the authors explain, many women develop “rejection sensitivity” through which she knows when to silence herself in order to survive, feel protected, or accepted. Women may silence themselves to avoid conflict and loss. Women may also self-silence if they believe self-sacrifice is a form of love and care, making them more valuable, as a way to raise their status in society. Some will conceal their true self to present the external false self that is expected by others and to conform to the social norms of feminine “goodness.” Those who have an “externalized self-perception” dependent on what others think of them lack confidence or suffer from perfectionism and are even more prone to strictly conform to perceived gender norms in order to fit in. The authors explain, she may hide her anger and sense of unfairness, as these displays are socially unacceptable for women. However, as Maji et al. describe, concealing one’s authentic self can lead to internalized anger, frustration, unmet needs, and risk becoming disconnected from others. Self-silencing is also considered a form of abandonment of one’s true self, perpetuates self-doubt, and has been linked to depression [49].

The confidence gap between men and women has gained attention through investigative journalists Claire Shipman of ABC News and Katy Kay of the BBC World News [50]. They report, women exhibit more perfectionism and are more likely to experience the “imposter syndrome,” in which they feel inadequate and fraudulent in their success, despite the evidence they are performing as well as men. The authors reported that the sense of mastery and confidence comes from learning from trial and error, but women miss out on opportunities to grow from mistakes when they are worried about being perfect, being liked, and fear failure. This may explain why women consistently underestimated their abilities and men consistently overestimate their abilities, though both perform equally well. Women are more likely to blame themselves (internal forces) for shortcomings, whereas men are more likely to blame external circumstances. These journalists go on to report that women are less likely to speak up or apply for a job unless they are absolutely certain they are correct in their statements or that they meet all of the stated job qualifications. Whereas, men will apply if they meet 60% of the qualifications and expect they will learn what they do not know on the job [50].

Zenger et al. found that the confidence gap between the genders starts at an early age. Between the ages of 8 and 14 years, a girl’s confidence drops 30%, and their fear of failure increases 150%. The perception of being “liked” drops from 71% to 38% in the early teen years. Perhaps this is due to the fact that adolescent girls get the message to value perfection and avoid risk, therefore, they may miss out on the opportunity to grow confident through learning from mistakes. At age 25, women will start to gain confidence and finally close the gap by age 60. During this period, from 25 to 60 years old, women gain 29 points on the confidence scale, compared to the men who gain 8.5 points during the same period of time. Because women lack confidence during the early stages of a career, she may not assert her competence and capabilities thus losing out on opportunities [17, 50].

Double standards and “the double bind” can be particularly challenging for successful women. Unlike men, in the current climate women are not perceived to be both assertive and warm, competent and “likeable,” simultaneously. The presence or absence of one infers the presence or absence of the other, called the “innuendo effect.” To say that a woman is “not likable” or “not a good fit” may sometimes be a euphemism for discrimination by gender norms against her ambition, even if unintentional. This can be confusing for women in leadership who get high marks and often exceed expectations on tasks but are held to “double standards” in managing work relationships. For example, researchers found that in the same performance reviews women may be told to “say no more often” and “not be afraid to make decisions that are unpopular,” while at the same time needing to “take others viewpoint into account” and “be more collaborative.” An aspiring female physician leader may try to be everything to everybody simultaneously. Or she may feel the need to conceal parts of herself (such as her strengths), unable to be fully authentic, expressive, or efficacious. This can be likened to the feeling of “walking a tight rope” or “walking on eggshells,” which feels isolating, stressful, and exhausting. The energy needed to conform to gender norms and be “liked” by everyone can detract from the primary work. Furthermore, the pressure to conform to the gender norms along with the biased double standards and double binds perpetuates the “hidden curriculum,” in which one generation of women teaches the next generation of women to conform to gender norms and conveys the message that her authentic self is unacceptable [42, 51,52,53].

Women are expected to put others first.

Compared to men, women have been shown to generally behave more collaboratively and look after the greater good, which has also been demonstrated in research and education [22]. Still women are often chastised for too much ambition and self-sacrifice to attain success, even if her ambition is to serve others. Per gender norms, she may be shamed for expecting credit for her own work. Some say, “nice girls don’t get the corner office” [54]. However, she may need to be “liked” and to “fit in” with the male-dominant “in-group” to get an opportunity. She may even be expected to downplay her achievements to be deemed more “likable.” To be “liked”, she may be relegated to the “helper role” by the dominant group, and vulnerable to others taking credit for her labor, such that being a “teamplayer” does not necessarily translate into advancement. This is a “double bind”. And if she were to express anger about the situation, her anger is more likely to be perceived as irrational and evidence of her lack of competence, whereas a man’s anger is more often attributed to external conditions and deemed reasonable, rational, and persuasive [51], which is a "double standard".

The “token” status of women in certain aspects of medicine does not fully explain the challenges they face to be accepted, fully participate, and advance in her field. By "token", we mean being less than 15% of a group. By raising the proportion of women in the group, it does not necesssarily resolve the obstacles women's face for upward mobility. In the comprehensive review on the subject of “tokenism” by Zimmer [55], the author provides some examples. For example, a decision-maker may purposefully promote a “token” outsider from the nondominant group as proof that he or she, the decision-maker, is not discriminatory and as evidence that they are compliant with expectations for desegregation, diversity, equity, and inclusion. However, these motivations do not guaruntee that those selected from the token group are most likely to succeed. Furthermore, it also suggests that a smaller proportion than than those qualified will be advanced. And furthermore, those token women that are hired into male-dominated fields such as medicine, police work, or the military are often segregated into positions with less power and less opportunity to advance. In contrast, men in female-dominated fields such as teaching and nursing are often disproportionately upwardly mobile and powerful. Moreover, as women rise in proportion in male-dominated fields, there was found to be a proportionate backlash of harassment to prevent them from advancing [55].

Women may fear rejection and retribution from the “in-group” that holds authority over her success. In a 2019 study of 7409 resident surgeons, 30% of women and 4% of men who felt sexually harassed feared the negative consequences if they complained about it. Hu et al. found that 65% of female surgery residents reported experiencing gender discrimination and 20% experienced sexual harassment, compared to 10% and 4% of males, respectively. Their supervising attending physicians were the most frequent source of sexual harassment (27%) and abuse (52%). This study also reported these experiences were associated with symptoms of burnout and suicidal thoughts, and these consequences were no longer present after adjusting for such mistreatment [56]. Women face hostility in the workplace and for reporting it [57]. A sexualized workplace can make women and men fearful of one another and therefore less likely to hire women in order to avoid risk, especially if it is believed that there is little to gain [58]. Perhaps this will resolve by normalizing gender diversity in the workplace.

Unconscious, implicit, second-generation bias is unintentional, yet omnipresent and detrimental to the advancement of women. Thus, it is imperative to deconstruct gender stereotypes that impose “double standards,” put women in the “double bind,” impose “self-silencing,” and undermine women’s confidence, forbid their ambition, and perpetuate the expectation that they behave according to gender norms to “self-sacrifice” and help others without the expectation of credit or reward. Making the necessary corrections role model for young girls and the next generation of female physician that their hope to be successful is acceptable and attractive, to be celebrated and not concealed. She should have permission to be simultaneously strong and warm, competent and likable, ambitious and collaborative, and authentic. This should strengthen her relationships and not detract from them. Like men, she should be able to be a parent and a professional. In achieving all of this, women should not be penalized with the “minority tax” in which she is tasked to resolve her own marginalization and devaluation, which further detracts focus from the primary work. It is a societal problem that requires a societal solution.

Closing the Gap

Negotiation training can help women navigate gender stereotypes. In “Negotiation Strategies for Women, Secrets to Success” by the Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School [24], the authors refute the claim that women are less skilled or assertive in negotiation; however, they negotiate less frequently and they often ask for less in order to protect against the backlash they face for breeching gender norms. The authors write that women are expected to be “accommodating and cooperative,” “nice and empathetic,” and “warm not assertive,” and to put others needs ahead of their own. The authors report that women may advocate forcefully for others, but not themselves, and ought to avoid negative masculine traits such as “dominance, arrogance, and entitlement” [24]. Their goal is to get their request granted while remaining likable, lest an “unlikability” judgement taint their career long term. Therefore, Professor Bohnet refers to Sheryl Sandberg’s advice to “combine niceness with insistence” to be “relentlessly pleasant” and “adhere to biased rules and expectations.” To avoid backlash, Professor Bowles recommends to “link aggressive demands to the needs of others, such as the organization,” and men and women ought to “audit their judgements for the subconscious tendency to view assertive women negotiators as unlikeable and overly demanding” and otherwise “reference relevant [objective] standards that would be difficult for the other side to ignore.” Bowles suggests communicating that she cares about the relationships and “legitimize” her negotiation behavior (e.g., such as by referencing that a “team leader suggested asking about compensation”).

Protecting against the backlash of breeching gender norms may be possible under some circumstances. For example, women perceived as “high status” may not experience as much backlash. Professor Bowles referred to the work by Professor Amy Cuddy and Professors Amanatallah and Tinsley in stating that even striking a pose or anything that generates a psychological sense of power can improve negotiations for women. Professor Bohnet relays how habitually facing your fears to “overcome stereotypical expectations through positive experiences” can increase your mastery and confidence in future negotiations [59]. Martin et al. found that women with “gender blindness” are more likely to feel confident, take initiatives, and take risks, than those who were “gender aware”; there may be some advantages to downplaying gender [60].

Women in male-dominated fields may benefit from being self-aware of their implicit tendencies to compensate for social constructs of gender norms, thus be more intentional in choosing a particular non-gendered response. For example, in “Tokenism and Women in the Workplace: The Limits of the Gender Neutral Theory” [55], Zimmer reports how women respond to being in positions that lack power or opportunities to advance. The author describes that those who lack power may exercise “authoritarianism and use of coercion over subordinates.” Those who lack opportunities for advancement may “respond with lower aspirations, parochialism and heightened commitment to nonwork rather than work activities.” If working alongside men in leadership, the “token” women may be “highly visible and intensely scrutinized” and respond by “overachievement or underachievement.” The dominant group may differentiate from the “outsider” by grossly exaggerating stereotypes, thus “boundary heightening”— increasing the obstacles for the "token" women to advance. The minority may experience a sense of isolation. Zimmer, citing Kanter, explains how some women may assimilate via “role encapsulation,” by acting within a female caricature – “the mother, the pet, the seductress, the iron maiden” – which influences the responses and evaluations from the dominant group but limits one’s ability to be a successful authentic leader. As Kanter wrote, “Tokenism is stressful: the burdens carried by tokens in the management of social relationships take a toll in psychologic stress, even if the token succeeds in work performance. Unsatisfactory social relationships, miserable self-imagery, frustrations from contradictory demands, inhibition of self-expression, feelings of inadequacy and self-hatred all have been suggested consequences of tokenism” [55, 61, 62].

Male sponsors and mentors are critical in the advancement of women [20, 25, 47]. After interviewing 500 company executives, Valerio et al. found that effective male “champions” considered gender equity integral to talent management, ensured equal opportunities for women, and involved both men and women in working toward gender equity. As “sponsors,” those in the dominant group often transfer some of their own social privilege and power in support of those they sponsor, to raise the visibility and credibility of the individual they sponsor. As “mentors,” the male senior executive integrated the mentee into their work to role-model and teach the leadership process. Ibarra et al. found that men were more likely to have been mentored by the CEO or another senior executive, 78% versus 69%. Within 2 years the men had received 15% more promotions. Furthermore, women in top positions were nearly twice as likely to be hired from outside their firm [63], meaning they were less likely to be hired into top positions at their home institution. It is also worthy to note, that in calling out gender bias, male champions often risk resistance from their own dominant in-group [25].

Engaging male allies can triple the chance that organizations will improve gender inclusion (96% versus 30%), say Johnson and Smith [64]. Smith et al. reported on reasons why male allies may remain on the sidelines and how they might be more willing to show more public support for gender equity [64, 65]. To overcome the “bystander effect,” in which a potential ally thinks someone else will do something about gender bias, the would-be bystanders might benefit from learning well established techniques that they can easily do to help in reduce unconcious bias [65]. For example, they might call out“microaggressions” by unwitting transgressors, in order to increase our collective awareness of bias. In the case of inactivity due to “psychological standing,” in which he may think it is not his place to speak on this issue in which he does not have a stake, the potential male ally may be more willing to engage if they knew their role was important and dignified [64, 65]. It is also important for women to appreciate that male allies sometimes give up their comfort in choosing to confront the dominant norms upheld by their own dominant in-group and sometimes risk “stigma by association” or the “wimp penalty” or may be considered less masculine for “power-sharing” and working collaboratively with women [64]. At the same time, men and women might wish to avoid the “pedestal effect” in which the appreciation of these male allies overshadow the long-sustained work done by women over the years, thus reinforcing the hierarchy. Similarly, the authors make note of the possibility of “fake male feminists” who may use the title for praise or to wield influence over women [64]. Overall, men and women will be more successful teaming up together to improve gender diversity, equity, and inclusion for the good of all. Both men and women would benefit from developing more self awareness and situational awareness for bias that mascarade as "the norm".

Role modeling, peer mentoring, and coaching can help reduce the sense of “otherness” that women may feel as the minority group at the top, especially if caught in one of the seemingly impossible "double binds" as described above. The Physicians Mom’s Group started online through Facebook in 2014 and now has over 70,000 members [66]. Here, female physicians share common experiences and find peer support. These peer groups provide role models, mentors, and coaches to help women reframe their experience and gain confidence in navigating the road to success [22]. President of Barnard College and cognitive scientist, Professor Bellock emphasized how important it is to practice cognitive reframing to combat the self-doubt, “learned helplessness,” and “imposter syndrome” that can sometimes result from environments with pervasive though subtle bias against women. She advocates that journaling is one method that can help to work through emotions, maintain confidence, and focus inner voice [67].

Affirmation will be needed to keep female talent engaged.

Women in leadership may be given resources to learn the skills needed for the job. She may be offered resources on how to have an “executive presence” in how she looks, speaks, and behaves. However, as Ibarra et al. advise, it is also important to be aware of the mismatch between how these traits are portrayed and perceived within current gender norms. Ibarra et al. describe that people will recognize the emerging female leader to not be what they expected (as they are accustomed to the current culture in that white males define executive leadership) and may accept or reject her or affirm or deflate her self-perception as an able leader. Thus, it is important to have opportunities for substantial achievements and to gain organizational endorsements. Ibarra et al. explain that through positive experiences, facing fear, and moving out of the comfort zone, the emerging leader will internalize her leadership identity. Ibarra et al. recommend facing the likability conundrum by neither being too feminine nor too hard charging, but to anchor in a sense of purpose that is value-aligned and serves the collective good. As the authors note, such an approach provides a compelling clear reason for action, conveys authenticity and trustworthiness, lends authority, and builds relationships [24].

How leaders might manage the “double bind” to be simultaneously tough and nice was investigated by Zheng et al. who interviewed 64 women in leadership (VP level or higher). They identified four “double bind” scenarios and five strategies to manage them. The four scenarios included 1) the need to be highly demanding of others while demonstrating warmth and care and 2) assert competence and decisiveness (strength) while showing vulnerability (weakness) and asking for collaboration (help), 3) advocating for oneself (so as not to feel taken advantage of) while focused on serving others (not being too aggressive with stakeholders to advance goals), and 4) maintaining distance (to generate leadership presence and maintain respect) while being approachable and accessible (without being perceived as informal, not serious, playing favorites). The strategy offered by the authors is to choose appropriate times when to use and signal niceness or toughness, distance or approachability, caring-collaborative or tough-directive traits for a particular situation and when it will first and foremost build relationships and trust and engage people. The authors suggest seeing assertiveness as a form of genuine care. They quote, “be tough on tasks and soft on people” [68]. Perhaps, this is not unlike parenting.

Implicit bias training can reduce bias.

Implicit, unconscious, or second-generation bias is that which is inherent to existing organizational structures and practices and go unnoticed but harbor unintentional prejudices with adverse effects on women’s access to opportunities and rewards. Unlike first-generation bias which has been made illegal in the workplace, second-generation bias goes unchecked (e.g., judging men and women differently for being assertive and advocating for themselves) [24, 69, 70]. Decision-makers who scored high on the implicit association tests (assessing one’s unconscious associations with stereotypes) are more likely to hire the status quo; they are more likely to perceive those who are different from themselves or the dominant in-group as a risky choice. If the individual’s difference is overt, i.e., cannot be concealed, it is even more likely that the decision-maker will infer competence based on the difference (e.g., gender, weight, race, etc.), making it more likely that the individual who is not in the “in-group” will be ostracized [71]. The implicit bias scores amongst health-care professionals are similar to those found in the general public, which is especially concerning given healthcare’s pressured fast-paced environment, and thus prone to overly rely on cognitive shortcuts, fraught with bias to make quick decisions [42, 52, 53, 72].

An implicit bias course may make individuals more self-aware of their inherent bias, making them less likely to inadvertently perpetuate it. Gonzalez et al. describe one such method in which a course might provide the psychological safety necessary for a “transformational learning experience", in which the learner is faced with a profound example of a biased-based experience, followed by critical reflection and a “deeply moving” guided discourse, resulting in growth-enhancing behavior change in which the learner is made more aware of bias and the adverse effects such that they are less likely to inadvertently prejudice their judgements in the future [73]. Also, Kang et al. bring our attention to the resources available from the Center for Worklife Law at the University of California Hastings College of Law and those created by the Engendering Success in the STEM consortium, namely, the “Bias Interpreters” and the “Bias Busting Strategies,” respectively [47].

A gender-diverse “promotion-focused” C-suite and board improve the financial success of the organization (as described above). Johnson et al. explained how the CEO and existing board members may inadvertently employ a “regulatory focus” in selecting individuals to steer the organization. Based on “regulatory focus theory", decision-makers may unconsciously employ a “promotion focus” or a “prevention focus” in considering what they have to gain versus what they have to lose, respectively. Those that adopted a “promotion focus” are less likely to engage in “group think” and achieve greater financial success. However, 84% of existing board members reported they are less likely to endorse an independent thinker. Existing board members may feel beholden to the CEO and the fellow board members who recruited them and wish to avoid dissenting views or see change as risk to be feared. The CEOs may prefer to appoint a known entity, such as other active CEOs. New members are likely to come from the same networks as the existing individuals and therefore likely to be of a similar race, sex, sociodemographic, behavioral, and interpersonal characteristics – predominantly white men (6% female). However, those with “promotion focus” were more likely to have diverse members that would challenge the CEO’s position. They also reported more enjoyable dynamics, avoided group think, and had better financial performance. Disruptions in the organization or board are a good time to integrate new members, say Johnson et al. [74].

The ability to report harassment without fear of retaliation or stigmatization improved reporting and increased satisfaction for medical students, reported Mangurian et al. [22]. In “Organizational best practices toward gender equity in science and medicine” published in the Lancet by Coe et al., it was noted that women are at risk of a “double dose of hostility,” given the prevalence of bias and risk of backlash for confronting it. Therefore, Coe et al. recommend that, as a starting point, those in power “listen to women, without comment, and believe them as they share their stories and experiences” [42].

Organizational accountability can improve diversity.

Given the prevalence of unconscious bias by gender and the fast-paced nature of healthcare prone to cognitive shortcuts reliant on pattern recognition, which reinforces the status quo, health-care organizations might set a goal for gender equity as a proportion of women in all facets of healthcare vertically and horizontally and create a plan to achieve it and check the progress regularly [23, 42].

Add more women to the pool of candicates.

Johnson et al. had 200 undergraduate students determine who to hire as the researchers changed the proportion of female candidates by changing the names on the applications for a fictitious nurse manager job. When two of three candidates were men, the participants were statistically more likely to hire a man for nursing leadership. In a follow-up study of university hiring patterns, Johnson et al. aggregated the finalists for jobs (an average of 4 individuals per finalist group for a total of 598) and examined those 174 who were extended a job offer. They found that the woman had zero chance of being hired if there was only one woman in the finalist pool, and she was 79 times more likely to be hired if there were two women in the finalist pool; however, the chances did not improve for each additional woman added to the pool [71]. To avoid anchoring expectations based on a male in the role, Johnson et al. suggested that the decision-makers interview the women first. Beware that when there is only one female candidate, her candidacy may be seen as a token of attempted gender diversity and undermine her chances [74].

Blinded assessments can reduce bias.

Bates et al. reported on ways that blinding applications can improve gender parity, just as orchestras had increased the hiring of females by 25% when they blinded the audition. Similarly, the authors’ commentary suggests that masking the gender of the principal investigator for grant applications to the National Institute of Health may reduce the bias against women’s grant applications [36].

Structured interviews have been shown to be less biased than unstructured interviews.

Bohnet et al. found that unstructured interviews are more prone to bias and less likely to determine job performance. For example, the authors found that three-quarters of the ratings that determined whether medical students were initially accepted to or rejected from medical school were based on perceptions and not objective facts, and it was not predictive of their future success. The authors explain that decision-makers can be overconfident in their own judgments and impressions, favoring those who “look the part” or “best person for the job,” often hiring someone like themselves, thus reenforcing the status quo and gender-based segregation of roles. Bohnet suggests keeping interviewers as independent as possible, compiling objective data, establishing a question set to which interviewers can compare answers, having a scoring system, scoring and submitting the interview immediately, and aggregating the assessment before the meeting to discuss the candidates. The authors suggest eliminating group interviews in order to reduce “group think” [23, 75].

A 6-point rating scale may be less biased than a 10-point rating scale when making assessments of men and women. Rivera et al. explain that when qualifications and behaviors are equal, women are less likely to be given a “perfect 10.” Men are more likely to receive praise and the women are more likely to receive scrutiny. The authors examined 105,034 college student ratings made by 369 instructors in 235 courses after switching from a 10-point to a 6-point rating scale and found this eliminated the gender gap in the assessment of these otherwise equally qualified individuals. In a follow-up study in which they had a male and female deliver the exact same lecture, the female was scored 10–20% lower on a 10-point scale by 400 students, but had equivalent marks on a 6-point scale. This is important because these assessments determine wages and who will be given opportunities to advance to the top level of the organization. Over time, these discrepancies add up, determining one’s level of success [76].

Wage transparency and an accurate accounting of work have been shown to shrink the wage gap between male and female physicians and slow the wage inflation for men [77]. As case in point, there was no pay gap for male and female otolaryngologists working in level I Veterans Affairs Medical Centers [78]. The authors attribute this in part to several decades of government-mandated initiatives starting with the 1963 Equal Pay Act. Salary data is transparent and publicly available. Stepwise increases are provided for years of service. Every 2 years, an objective review including an updated market evaluation is available. When oversights occur, adjustments can be made at later dates and retroactively applied. These researchers expanded the work to examine whether this phenomenon held true for other surgeon specialists. On univariate analysis, there was no difference in pay across 13 surgical subspecialties. On multivariable linear regression analysis, gender was a significant predictor of pay (p < 0.001), but the absolute differences were substantially reduced when compared to other work environments and absent in some specialties [79]. Other models of gender-blind value-based payments exist including the Mayo Clinic and Kaiser Permanente. Common themes emerge: similar starting salaries, stepwise increases, objective market review, and pay transparency.

Annual salary review can correct course. For example, as Warner et al. reported, Johns Hopkins found they were paying female physicians 3.4% less per FTE salary and 8.6% less in total salary. The University of California San Francisco Medical School could not justify the wage gaps between male and female physicians under the California Fair Pay Act and made $1.58M in salary adjustments [8]. Other prestigious medical schools followed suit.

Institutional funding, bridge grants, and skill building can help retain and promote junior faculty [23]. Female junior faculty are eager for professional development programs. Valantine et al. reported that of the 657 who participated in workshops, 64% were women. The topics covered included how to negotiate and delegate, write grants and manuscripts, communicate and present, time management, navigate work-life balance and implicit bias, and get reappointed and promoted.

Recognize the value of clinical work and clinical educators, which has a predominance of women. For example, Duke University, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital have created ways to recognize clinical prowess and some have created a tenure track for these positions [21].

A more flexible “academic clock” may allow more women in academia to achieve full potential [23, 36, 80]. Advancement in academic medicine is often dependent on the rate at which a faculty member procures grants, publishes papers, and becomes engaged and renowned in their field. Often, eligibility for key grants and promotion is time limited, within the first 10 years of one’s career. This may be when women, who have already delayed childbearing during training, now plan to have their children. An updated, flexible academic “clock” supported by academic promotion policies may be more effective in retaining and engaging top talent and promoting diversity, as top talent is a precious resource. Valentine et al. describe “Academic Biomedical Career Customization” with flexible policies that allow women to be available at home at critical times, such as tenure track extensions and parental leave, individualized career plans, flex up and down in research, patient care, administration and teaching, and facilitating physician engagement and satisfaction [20].

Support for work-life integration eliminates obstacles for women, especially mothers. Per the review by Mangurian et al., currently family leave policies at US medical schools are not compliant with the advice physicians give patients and society. For example, the Academy of Pediatrics is recommending 6 months of paid leave after childbirth, and most US medical schools only allow 8 weeks. Furthermore, family leave is often restricted to the “primary caregiver,” which often defaults to the women to care for the children and elderly while limiting the option of “cooperative parenting” or shared caregiving, especially as half of physician mothers are married to a physician father. Mangurian et al. recommends a universal standard of at least 12 weeks paid childbearing leave, additional 4–12 weeks for childrearing for all new parents, lactation rooms and time to pump breast milk, on-site childcare, paid catastrophic leave for life-threatening illness or injury, flexible schedules and promotion policies, and legislative protection against employment discrimination against those with family caregiving responsibilities [22]. In Scandinavia where there is maternity-paternity leave for children under 1 year and accessible and affordable childcare for children under 6 years old, work and children were not considered an obstacle, and it has improved women’s position in the workplace [41]. Warner et al. cite that companies such as Home Depot, Clif Bar, and Patagonia argue there is a strong business case for offering on-site child care, especially in improving engagement and reducing turnover; furthermore, 91% of the cost could be recouped in tax credits. The business case is likely to be more true for physicians, with replacement costs ranging from $250,000 to $1M per physician [8, 81]. Valantine et al. argue now that 50% of the American physician workforce comprises women, and work policies should not remain predicated on the idea that one spouse stay at home full-time [20].

Financial Freedom

Women need to achieve financial independence, perhaps more than men. On average, women live longer, are paid less, and are more likely to have work gaps. These gaps affect early, middle and late career. Childbearing and child rearing may affect early and early-middle career, and acute and/or chronic illness and care of elderly and aging family members may be more likely to affect middle and/or late career. Divorce and job prospects dependent on her partner’s professional obligations can also affect a woman’s career. Since women live longer than men and her wages peak earlier, and she is less likely to have as much invested for retirement; she is more likely to be widowed and at risk of financial “illness.” Financial self-care reduces stress, increases confidence, and allows one to have more control over life choices. Strategies for achieving financial health and financial independence depend on managing debt, behavior (i.e., living below one’s means), investing, and asset protection [82].

Manage debt by paying off high interest loans first. Alternatively, choose to pay off a smaller debt first and use the momentum from that success to inspire the next round of debt reduction. What about paying off medical school debt? Generally, if the interest rate is low, your money may be better spent investing in another investment vehicle with higher returns and paying down the difference. If the interest rate is high, it is better to pay off the student loan directly.

Set goals, budget, and save.

In addition to traditional forms of information, such as books and brokers, there are a number of online resources such as The White Coat Investor [83], Physician on FIRE (Financial Independence and Retire Early) [84], and Wealthy Mom MD [85]. These resources are geared toward physicians and women physicians, respectively. In addition to saving and investing, factors such as specialty choice, practice type, and geography can substantially influence one’s ability to build financial independence [6]. The highest paid specialties are typically procedural and/or surgical in nature. On average, owners/partners make more than independent contractors, who make more than employees. While compensation in the highest paying metro areas may be 37% higher, the cost of housing can vary tenfold, so living in a less expensive city with a slightly lower pay check may make more sense in the long-term. National cost indexes can be used to compare cost of living in metro areas to make sound decisions based on professional opportunities, family needs and quality of life.

Minimize medical school debt.

For those of you reading this before or during medical school, minimizing school debt can help reduce stress and achieve financial freedom. In 2018, the median debt for medical student graduates who borrowed money was $200,000; this debt may increase by 20–50% by the completion of training [82]. Unfortunately, increased medical student debt has been associated with delays in making major life decisions such as marriage, children, and/or purchase of a home [86]. Several studies have associated medical school debt with choosing higher paying specialties [87]. In addition, medical student debt may be negatively associated with mental health, well-being and academic outcomes [87]. Some strategies to minimize school debt include choosing a state school over a private institution, sharing housing with a roommate, and selecting a less expensive city or one with good housing subsidies.

Investing is a critical part of growing wealth. Compared to men, women tend to be more likely to save and less likely to invest, which can hurt long-term growth. While some prefer traditional financial advisors, there are now online robo investing tools such Ellevest (ellevest.com), Betterment (betterment.com) and Wealthfront (wealthfront.com) to consider as part of your investment strategy. Ellevest is one of the few designed specifically for women and takes into account that women have a higher risk of gaps in work and a longer life span on average. Additionally, Ellevest provides resources to help educate oneself on financial decision making. Readers are advised to do their own research and vetting prior to making any investment decisions.

Anticipate life events, learn and plan accordingly.

Many of the tools available are beyond the scope of this chapter, but they may be found in some of the online resources listed above. It is useful to educate yourself on topics such as the financial benefits of marriage and the cost of divorce, managing a dual physician household, delayed child-bearing and the cost and logistics of fertility treatments, the cost of childcare and education, the state variations in child education pre-tax investment devices, the rules for calculating and claiming social security benefits, retirement accounts, disability insurance, health insurance, life insurance, malpractice insurance, umbrella insurance, and state to state variations on what aspects of your personal financial portfolio would be at risk in case of a malpractice suit. While you build your financial security, you will also have to defend it.

Financial independence is defined by some as the ability to live on 4% of the overall value of one’s investment portfolio annually [82]. For example, a $1,000,000 portfolio should generate $40,000 of income per year on average, a $2,000,000 portfolio should generate $80,0000 per year on average, and a $3,000,000 portfolio should generate $120,000 per year on average. Keep in mind that investing for a steady and reliable source of income is different than investing for long-term growth; the expected return on investment will be lower on average, but less volatile. Another simple way to calculate the amount needed to reach financial independence is to multiply one’s annual cost of living by 25. For example, if your family lives on $200,000 per year, you will need a portfolio worth $5,000,000 to be financially independent.

Invest in yourself.

You must invest in your most important asset: yourself. Disability insurance, particularly specialty-specific insurance and one that is portable, can help insure you against loss of income. Life insurance may be important if you have others that depend on you. Liability coverage can help protect you and your assets from other types of risk. Most importantly invest in your physical and mental health, carving out time to invest in your rest and rejuvenation for a long life of personal and professional success.

Conclusion

Now that women have achieved parity in medical school, it is essential to be sure that women physicians have equal opportunity to achieve career success. The reasons for the gaps in pay and promotion are multifactorial and will require a multifaceted approach involving both men and women, individuals, and institutions. Personal and professional freedom to participate and achieve rank and reward is a key component to women physicians’ professional success, financial independence, and mental well-being.

References

Bulluck P. N.I.H. head calls for end to all-male panels of scientists. New York Times. 12 June 2019.

Manzoor M, Thompson K. Delivered by women, led by men: a gender and equity analysis of the Global Health and Social Workforce: World Health Organization; 3 Mar 2019. 60 p.

Heiser S. More women than men enrolled in U.S. medical schools in 2017: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2018 [updated December 18, 2017]. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/more-women-men-enrolled-us-medical-schools-2017.

Overberg P, Adamy J, Thuy L, Ma J. What’s your pay gap? wsj.com: Wall Street Journal; 2016 [cited 2016 May 17]. Available from: http://graphics.wsj.com/gender-pay-gap/.

Miller C. Pay gap is because of gender, not jobs. New York Times. 23 Apr 2014.

Doximity 2019 physician compensation report: doximity. 2019. Available from: https://blog.doximity.com/articles/doximity-2019-physician-compensation-report-d0ca91d1-3cf1-4cbb-b403-a49b9ffa849f.

Freund KM, Raj A, Kaplan SE, Terrin N, Breeze JL, Urech TH, et al. Inequities in academic compensation by gender: a follow-up to the National Faculty Survey Cohort Study. Acad Med. 2016;91(8):1068–73.

Warner AS, Lehmann LS. Gender wage disparities in medicine: time to close the gap. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(7):1334–6.

Newcomb A. Women’s earnings lower in most occupations 2018 [May 22]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2018/05/gender-pay-gap-in-finance-sales.html.

Lo Sasso AT, Richards MR, Chou CF, Gerber SE. The $16,819 pay gap for newly trained physicians: the unexplained trend of men earning more than women. Health Aff. 2011;30(2):193–201.

Carr PL, Raj A, Kaplan SE, Terrin N, Breeze JL, Freund KM. Gender differences in academic medicine: retention, rank, and leadership comparisons from the National Faculty Survey. Acad Med. 2018;93(11):1694–9.

Desai T, Ali S, Fang X, Thompson W, Jawa P, Vachharajani T. Equal work for unequal pay: the gender reimbursement gap for healthcare providers in the United States. Postgrad Med J. 2016;92(1092):571–5.

Baker LC. Differences in earnings between male and female physicians. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(15):960–4.

Pollart SM, Dandar V, Brubaker L, Chaudron L, Morrison LA, Fox S, et al. Characteristics, satisfaction, and engagement of part-time faculty at U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2015;90(3):355–64.

Foundation TP. Health Reform and the Decline of Physician Private Practice. A White Pater Examining the Effects of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act on Physicians Practices in the United States: Merrit Hawkins; 2010. p. pp 116.

Arnett DK. Plugging the leaking pipeline: why men have a stake in the recruitment and retention of women in cardiovascular medicine and research. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8(2 Suppl 1):S63–4.

Zenger J, Folkman J. Research: women score higher than men in most leadership skills. Harvard Business Review. 2019.

Murphy H. Picture a leader. Is she a woman? New York Times. 16 Mar 2018.

Rosenstein AH. Strategies to enhance physician engagement. J Med Pract Manage. 2015;31(2):113–6.

Valantine H, Sandborg CI. Changing the culture of academic medicine to eliminate the gender leadership gap: 50/50 by 2020. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1411–3.

Rotenstein L. Fixing the gender imbalance in healthcare leadership. Harvard Business Review. 2018.

Mangurian C, Linos E, Urminala S, Rodrigez C, Jagsi R. What is holding women in medicine back from leadership. Harvard Business Review. 2018.

Valantine HA, Grewal D, Ku MC, Moseley J, Shih MC, Stevenson D, et al. The gender gap in academic medicine: comparing results from a multifaceted intervention for Stanford faculty to peer and national cohorts. Acad Med. 2014;89(6):904–11.

Program on Neotiation HLS. Harvard University; 2013.

Valerio A, Sawyer K. The men who mentor women. Harvard Business Review. 2016.

Turban S, Wu D, Letian LT. Research: When gender diversity makes firms more productive. Harvard Business Review. 2019.

Prince LA, Pipas L, Brown LH. Patient perceptions of emergency physicians: the gender gap still exists. J Emerg Med. 2006;31(4):361–4.

Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Figueroa JF, Orav EJ, Blumenthal DM, Jha AK. Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates for medicare patients treated by male vs female physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):206–13.

Delgado A, Lopez-Fernandez LA, Luna JD. Influence of the doctor’s gender in the satisfaction of the users. Med Care. 1993;31(9):795–800.

McMurray JE, Linzer M, Konrad TR, Douglas J, Shugerman R, Nelson K. The work lives of women physicians results from the physician work life study. The SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(6):372–80.

Files JA, Mayer AP, Ko MG, Friedrich P, Jenkins M, Bryan MJ, et al. Speaker introductions at internal medicine grand rounds: forms of address reveal gender bias. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2017;26(5):413–9.

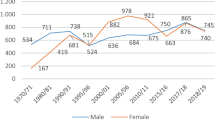

Ruzycki SM, Fletcher S, Earp M, Bharwani A, Lithgow KC. Trends in the proportion of female speakers at medical conferences in the United States and in Canada, 2007 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e192103.

Kuhlmann E, Ovseiko PV, Kurmeyer C, Gutierrez-Lobos K, Steinbock S, von Knorring M, et al. Closing the gender leadership gap: a multi-centre cross-country comparison of women in management and leadership in academic health centres in the European Union. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15(1):2.

Jagsi R, Guancial EA, Worobey CC, Henault LE, Chang Y, Starr R, et al. The “gender gap” in authorship of academic medical literature – a 35-year perspective. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(3):281–7.

Jena AB, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in physician salary in US public medical schools. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1294–304.

Bates C, Gordon L, Travis E, Chatterjee A, Chaudron L, Fivush B, et al. Striving for gender equity in academic medicine careers: a call to action. Acad Med. 2016;91(8):1050–2.

Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Satele D, Freischlag J. Physicians married or partnered to physicians: a comparative study in the American College of Surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(5):663–71.

Jolly S, Griffith KA, DeCastro R, Stewart A, Ubel P, Jagsi R. Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by high-achieving young physician-researchers. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(5):344–53.

Ly DP, Jena AB. Sex differences in time spent on household activities and care of children among US physicians, 2003-2016. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(10):1484–7.

Adesoye T, Mangurian C, Choo EK, Girgis C, Sabry-Elnaggar H, Linos E. Perceived discrimination experienced by physician mothers and desired workplace changes: a cross-sectional survey. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):1033–6.

Riska E. Towards gender balance: but will women physicians have an impact on medicine? Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(2):179–87.

Coe IR, Wiley R, Bekker LG. Organisational best practices towards gender equality in science and medicine. Lancet. 2019;393(10171):587–93.

McNamee S, MIller R. The meritocracy myth. 2nd ed. Landham: Rowman & Littlefield; 2009.

Thomas K, Mack D, Mantagliani A. The arguments against diveristy: are they valid? In: Stockdale MS, Crosby FJ, editors. The psychology and management of workplace diversity. Malden: Blackwell Publishing; 2004.

Harris C. Whiteness as property. Harv Law Rev. 1993;106(8):1707–91.

Markovitz D. How life became an endless, terrible competition. The Atlantic. Sept 2019.

Kang SK, Kaplan S. Working toward gender diversity and inclusion in medicine: myths and solutions. Lancet. 2019;393(10171):579–86.

Delgado A, Saletti-Cuesta L, Lopez-Fernandez LA, Toro-Cardenas S, Luna del Castillo J d D. Professional success and gender in family medicine: design of scales and examination of gender differences in subjective and objective success among family physicians. Eval Health Prof. 2016;39(1):87–99.

Maji S, Dixit S. Self-silencing and women’s health: a review. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2019;65(1):3–13.

Kay K, Shipman C. The confidence gap. The Atlantic. 2014. pp. 56–66.

Menendez A. The likeability trap. Harper Business: New York; 2019. 256 p.

Rodriguez JE, Campbell KM, Pololi LH. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax? BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:6.

Fallin-Bennett K. Implicit bias against sexual minorities in medicine: cycles of professional influence and the role of the hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 2015;90(5):549–52.

Frankel LP. Nice girls still don’t get the corner office. New York: Business Plus Books; 2014.

Zimmer L. Tokenism and women in the workplace: the limits of gender-neutral theory. Soc Probl. 1988;35(1):64.

Hu YY, Ellis RJ, Hewitt DB, Yang AD, Cheung EO, Moskowitz JT, et al. Discrimination, abuse, harassment, and burnout in surgical residency training. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(18):1741–52.

Dampier C, Lieff S, LeBeau P, Rhee S, McMurray M, Rogers Z, et al. Health-related quality of life in children with sickle cell disease: a report from the Comprehensive Sickle Cell Centers Clinical Trial Consortium. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;55(3):485–94.

Tarbox K. Is #MeToo backlash hurting women’s opportunities in finance? Harvard Business Review. 2018.

Brody DS, Miller SM, Lerman CE, Smith DG, Lazaro CG, Blum MJ. The relationship between patients’ satisfaction with their physicians and perceptions about interventions they desired and received. Med Care. 1989;27(11):1027–35.

Martin A. Women benefit when they down play gender. In: Torres N, editor. Defend your research. Harvard Business Review; 2018.

Kanter R. Men and women of the corporation. New York: Basic Books; 1977.

Kanter R. A tale of “O” - on being different in an organization. New York: Harper Row; 1980.

Ibarra H, Carter N, Silva C. Why men still get more promotions than women. Harvard Business Review. 2010.

Johnson WB, Smith DG. How men can become better allies to women. Harvard Business Review. 2018.

Smith DG, Johnson B. Lots of men are gender-equality allies in private. Why not in public? Harvard Business Review. 2017.

Physicians Mom’s Group (PMG) [Available from: https://www.facebook.com/groups/PhysicianMomsGroup/.

Bellock S. Research-based advise for women working in male-dominated fields. Harvard Business Review. 2019.

Zheng W, Kark R, Meister A. How women manage the gender norms of leadership. Harvard Business Review. 2018.

Ibarra H, Ely R, Kolb D. Educate everyone about second-generation gender bias. Harvard Business Review. 2013.

Wikipedia. Second-generation gender bias: Wikipedia; 2019. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second-generation_gender_bias.

Johnson SK, Hekman DR, Chan ET. If there’s only ONe woman in your candidate pool, there’s statistically no chance she’ll be hired. Harvard Business Review. 2016.

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, Merino YM, Thomas TW, Payne BK, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):e60–76.

Gonzalez CM, Garba RJ, Liguori A, Marantz PR, McKee MD, Lypson ML. How to make or break implicit bias instruction: implications for curriculum development. Acad Med. 2018;93(11S Association of American Medical Colleges Learn Serve Lead: Proceedings of the 57th Annual Research in Medical Education Sessions):S74–81.

Johnson SK, Davis K. CEO’s explain how they gender-balanced their boards. Harvard Business Review. 2017.

Bohnet I. How to take the bias out of interviews. Harvard Business Review. 2016.

Rivera L, Tilcsik A. One way to reduce gender bias in performance review. 2019.

Rotenstein L, Dudley JC. How to close the gender pay gap in U.S. medicine. Harvard Business Review. 2019.

Dermody SM, Litvack JR, Randall JA, Malekzadeh S, Maxwell JH. Compensation of otolaryngologists in the veterans health administration: is there a gender gap? Laryngoscope. 2019;129(1):113–8.

Maxwell JH, Randall JA, Dermody SM, Hussaini A, Rao H, Nathan AS, et al., editors. Pay transparency among surgeons in the veterans health administration: closing the gender gap. American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress. 25 Oct 2019. San Francisco.

Villablanca AC, Beckett L, Nettiksimmons J, Howell LP. Career flexibility and family-friendly policies: an NIH-funded study to enhance women’s careers in biomedical sciences. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2011;20(10):1485–96.

Shanafelt T, Goh J, Sinsky C. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1826–32.

Royce TJ, Davenport KT, Dahle JM. A burnout reduction and wellness strategy: personal financial health for the medical trainee and early career radiation oncologist. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2019;9(4):231–8.

J D. The White Coat Investor 2020. Available from: https://www.whitecoatinvestor.com/.

Physician on FIRE (Financial Independence and Retire Early), 2020. Available from: https://www.physicianonfire.com/.

Koo B. Wealthy Mom MD. 2020.

Rohlfing J, Navarro R, Maniya OZ, Hughes BD, Rogalsky DK. Medical student debt and major life choices other than specialty. Med Educ Online. 2014;19:25603.

Pisaniello MS, Asahina AT, Bacchi S, Wagner M, Perry SW, Wong ML, et al. Effect of medical student debt on mental health, academic performance and specialty choice: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7):e029980.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Olson, K.D., Litvack, J.R. (2020). Mind the Gap: Career and Financial Success for Women in Medicine. In: Stonnington, C., Files, J. (eds) Burnout in Women Physicians. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44459-4_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44459-4_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-44458-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-44459-4

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)