Abstract

Foster care is a strong risk factor for youth homelessness, with an alarmingly high rate of unstable housing occurring within several years after transitioning out of care. The current system of care in most jurisdictions forces youth to be financially and socially independent at an earlier age despite insufficient preparation, thereby making the transition out of care an extremely high-risk period. The sudden autonomy in one’s schedule, finances, employment, education, and health can become overwhelming. As a result, engagement with work and school, and even government welfare services, can often be discontinuous. Various proposals have sought to improve outcomes, including legislation to extend foster care to age 21, with a greater emphasis on building relationships and resources to help navigate complex systems. Healthcare providers can be important advocates for youth in care by championing their medical and psychological needs and serving as a bridge that lasts beyond foster care.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Background

Over 440,000 children and adolescents are in foster care in the United States, and nearly 20,000 age out of care annually [6]. The foster care system is designed to protect abused and neglected children from further abuse; thus when the safety of a child cannot be reconciled within his or her home, the child is removed and placed by a government agency into a relative’s home, foster home, group home, or residential treatment, all of which is referred to as foster care in this chapter.

Foster care ends at different ages depending on the jurisdiction. Legislation in recent years allows US states to extend foster care until age 21, although it may still end at age 17–19 for youth in certain states or for those who decline extended services. The United Kingdom has formally adopted 21 years as the upper age limit across the nation. Most provinces in Canada still end foster care at age 18 or 19, and most Australian states, where the term “out-of-home care” is also used, similarly end at age 17 or 18 [5]. However, very recently, there has been successful legislative advocacy in some of these jurisdictions to increase the age limit to 21.

Youth who have previously been in or are currently in foster care, collectively termed youth in care, make up a substantial portion of the homeless population. Youth in care have frequently had a lifetime of unstable housing, including frequent moves, nonfamily-based living situations such as group homes, and substandard or tenuous housing situations as young adults [16]. The pathway to homelessness for youth in care is distinct from other homeless youth.

Being a youth in care is a strong precursor for homelessness. One study that prospectively followed a large cohort of youth in care into young adulthood found that a sobering 36% of youth in care had experienced homelessness by age 26 [17]. In general, studies estimate that 12–46% of youth in care become homeless as adults [23], with many youth experiencing homelessness within just 6–12 months of leaving care [16, 18]. More alarmingly, youth in care have higher rates of eventual homelessness than adults who experienced abuse as children but who were not removed from their homes [21]. Former youth in care are more likely to be homeless compared to youth who grew up in poverty but were not removed from their homes [23].

As an added consideration, these rates likely also underestimate the true burden of housing instability, since most studies were limited to measuring shelter or street-based homelessness but did not include disguised forms of homelessness such as “couch-surfing” or staying with a friend. Conversely, from the perspective of people who are homeless, there is an overrepresentation of former youth in care. Shelters, street-based homeless populations, and programs for homeless mothers see high frequencies of former youth in care with most reports ranging between 20% and 35% [21]. Therefore, whether one looks at groups of homeless people or groups of former youth in care, a strong association exists between a history of being in care and risk of later homelessness.

“One study [...] found that a sobering 36% of youth in care had experienced homelessness by age 26.”

Issues Affecting Youth in Care

Youth in care who become homeless commonly live unstable lives even before they are homeless. The impact of losing one’s stable housing is exacerbated by a system that not only pushes youth in care to be socially and financially independent at an earlier age than is expected for the most other youth but also inadequately prepares these youth for independence. Youth in care can have unmet life skills, gaps in education, under-recognized health and developmental challenges, poor employability, and premature detachment from social supports. These youth commonly receive fragmented services, including housing, school, and healthcare, which seriously impede their healthy development and preparation for adult life [14].

Housing

Youth in care may be moved numerous times throughout their adolescent years, and these changes in residence commonly not only involve changing homes and caretakers but often also schools, primary care physicians, and peer groups, resulting in few relationships sustained over time. Former youth in care who become homeless are more likely to have been in group homes, had frequent moves, and had interactions with the juvenile justice system [16], indicating a pattern of trauma, loss, and instability starting before homelessness.

Group homes, where many struggling youth in care eventually find themselves, can come with their own challenges. The most striking testimonies reflect on the unforgiving rigidity of rules, the lack of privacy from surveillance, and the extent of peer-on-peer bullying in some group homes, which serve to undermine the healing and sense of security of traumatized adolescents. For girls and young women, being placed in one of the extremely rare female-only group homes can be invaluable in alleviating their constant vigilance against sexual assault [12].

Education

Youth with higher education outcomes significantly increase their earnings [23], but youth in care are less likely to attend post-secondary education, such as a college, university, or trades program. High school dropout rates can be over 50% in some provinces or states [20]. Too often youth in care have unrecognized learning disabilities, significant gaps in their education, and incomplete school files, revealing the pervasive systemic challenges confronting the current foster care system.

Poverty-related barriers to high school attendance, including school fees, uniforms or school-appropriate clothing, consistency of personal hygiene, and transportation, are exacerbated when youth are in care and trying their best to keep up with their education [12]. School truancy is often an unintended and disappointing sequelae of unstable housing. This is especially true in instances where a student may move foster homes multiple times during a school year or even slip in and out of homelessness.

“High school dropout rates can be over 50%...”

Employment

Unemployment and underemployment are big challenges for youth in care. Although many are employed when they leave care, half lose their employment within 3 years [23]. In addition, employed youth in care earn 50% less than their peers who are not in care [23]. Without a financial safety net from their parents or family, as many other youth have, youth in care can experience drastic consequences of what might be otherwise developmentally appropriate experimentation or exploration of new forms of employment and income-generation behaviors, being unable to turn to their parents during difficult times. They may lack skills and guidance for new tasks, such as paying rent and utilities on time and managing budgets.

Health

Many youth in care experience specific health issues that can impact their housing stability and well as their experience with homelessness. Their frequent childhood histories of loss; trauma; disrupted early attachment; household dysfunction; and emotional, physical and/or sexual abuse have serious implications for their health [17]. Physical and mental health symptoms, which often derive from the same sources of trauma, can interfere with regular employment and reaching out to social services.

Typically, physical and mental health deteriorate sharply following transition out of care. Within 18 months after leaving foster care, 30% of former youth in care had become young parents and 48% reported depression or other major mental health issues [24, 26]. At ages 17 or 18, these vulnerable youth are two to four times more likely to suffer from mental health disorders compared to those in the general population [19]; however, only a small minority receive professional help [19, 25]. These rates are unsurprisingly higher in those who become homeless [17]. Furthermore, adults formerly in care are consistently found to have higher rates of chronic health problems, such as asthma, diabetes, hypertension, and epilepsy [32].

Since youth with multiple childhood adverse experiences are more likely to experience adult health problems [17], youth in care may be at a lifelong disadvantage if they cannot navigate the adult healthcare system, which can often be unforgiving of youth. For example, a specialist clinic may terminate a doctor–patient relationship for reasons such as missed appointments. There are numerous obstacles in seeking healthcare for youth in care, including a lack of continuity in care, insufficient communication with healthcare providers, and insufficient training, information, and support provided for foster parents [22]. Child protection teams rarely have sufficient case management personnel to support even the children and youth with known chronic health conditions.

“Within 18 months after leaving foster care, 30% of former youth in care had become young parents and 48% reported depression or other major mental health issues.”

Social and Familial Attachment

Youth in care often lack consistent and strong family connections on whom to rely for support during tough periods of their life [16]. Young people entering care as adolescents are a high-risk subgroup, as they are frequently placed into group homes or independent living where there are fewer adult supports and attachments [16].

Youth removed from their homes and placed in foster care, even homes in which they had been victims of child abuse and neglect, commonly sustain strong attachments to their parents and caregivers from early childhood. Given these bonds, it is not unusual for youth in care to seek out and attempt reunification with their original family. In working with youth in care, it is essential to respect these relationships and to avoid prejudgment or negative characterizations of loved family members.

Marginalization

Indigenous and visible minority youth have long had a disproportionately high representation in developed nations’ foster care systems. Racially discriminatory attitudes in their foster homes can drive youth in care to leave those unsafe and unsupportive homes and become homeless. In addition to their lived experience of targeted victimization, these youth are often distrustful of fostering due to historical victimization in the forms of colonialism, slavery, and child segregation, which is inherited through generational trauma [12].

Similarly, LGBT youth can experience discrimination in foster homes, group homes, and youth shelters. These youth often enter foster care as a result of fleeing homophobia in their home of origin. Schools and social services may also not be LGBT-friendly, which forces these youth into further vulnerability and disengagement and typically to conceal their LGBT identity as a survival mechanism [12].

“[Youth in care] are often distrustful of fostering due to historical victimization in the forms of colonialism, slavery, and child segregation…”

Relations with Child Protection Services

Child protection services aimed solely at identifying safe living situations may not be adequately equipped to connect youth with needed mental health and counseling services, social supports, and developmental assessments that can be critical to their health [8, 10].

Parental neglect is by far the most prevalent reason for removal by child protection agencies from a family home. This stems from risk factors such as conditions of poverty, poor housing, parental incarceration or death, domestic violence, and parental substance abuse [28]. Consequently, many youth in care originate from families who may have similarly struggled with housing instability, frequent moves, and insufficient financial resources. The back and forth between inadequately stable housing and homelessness can be a destructive cycle that recurs through their childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood.

Understandably, many youth in care have a strong distrust of child protection services and related government agencies. This may introduce additional complexity in efforts to support their transition to independence.

Transition Out of Care

Transitioning out of care has been established as a period of great risk for an already marginalized group, which stems from an unrealistic expectation that they will become newly independent young adults with little to no support. A lack of coordination between multisystem services often means that youth “fall through the cracks” [8]. Youth can also become disconnected from services when they age out of care because they do not know or trust the new systems. As a consequence, despite youth service providers who may make every effort to facilitate connections, the history of trauma and disrupted relationships experienced by many youth in care creates barriers to following-up on such referrals [8].

One tragic case in Vancouver, Canada, that was subject of a government review illustrates the consequences that can befall youth in care as they abruptly transition out of care. On the last government agency note written for one youth who experienced frequently changes in foster homes as well as homelessness, her welfare worker wrote, “The child is one month from turning 19 and unfortunately she is still binge drinking heavily and appears not to be overly concerned about having anywhere to live at age 19.” In contrast, an email from her foster parent expresses concern that “[the youth’s] anxiety builds as her move out date approaches,” implying that the youth’s detached behavior recorded by the welfare worker was an expression of stress and worsening mental health. This youth subsequently died from an overdose 11 months later [31].

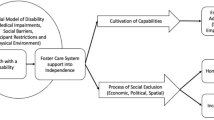

Accessing social services when a youth is still in care is often much easier than after they transition out of care, since the responsibility transfers from the welfare worker to the youth at the time of transition. In many jurisdictions, funding for psychological diagnostic investigations, which may be an avenue to qualify for necessary adult supports, is dependent on a youth’s age and may be available only for those still considered minors. A former youth in care would be also simultaneously charged with new responsibility for finances, housing, food, and more, which can be overwhelming for a youth who may be living with a disability. Hence, there is a vicious cycle between disability and social needs.

Young adults seeking social services are not viewed any differently than adults seeking those same services, even though their needs are profoundly different from the needs of adults in the general population [31]. For example, a young adult attempting to access welfare income may have overwhelming difficulty trying to navigate the complexities of the system due to their inexperience with social services. Conflicting feelings about whether or not to access social services can also interfere with seeking help and following the multiple steps properly.

Adequately supporting the transition out of care is an essential component of preventing youth homelessness. The American Academy of Pediatrics emphasizes that during their period of transition, youth in care may innately have “difficulty assuming tasks of young adulthood which require rapid interpretation of information,” such as key skills needed for employment and independent living [3]. Pediatricians and other physicians, nurses, social workers, and other professionals who work with youth in care play a vital role in supporting these youth and advocating for the transition services and resources that they need.

Promising Interventions and Strategies

Policy Changes

Extending foster care until age 21 has long been advocated by numerous social policy groups. The focus on extending the age of eligibility grew after convincing advocacy efforts demonstrated the benefits for youth in care, as well as for the government in fiscal savings. Currently, policies are beginning to shift in the United States and Canada, with more jurisdictions continuing some or all foster care services until age 21. It is not clear if extending foster care decreases homelessness in this population, but at the very least, it delays homelessness [17]. Since most youth in the general population rely on emotional and financial support from their families through young adulthood, this policy shift is a first-line effort to provide a better and more equitable life for youth in care.

However, even when available, extending foster care until age 21 is not enough. Policies that ensure adequate housing, fiscal availability, job readiness, and educational access are essential. Expert advocacy groups exist in the United States and Canada that provide extensive recommendations and creative ideas to plan for youths’ transition out of care. These include interventions that interface more directly with youth, such as building savings accounts, assessing gaps in life skills, and facilitating connections with mentors and families.

Strong Foster and Adoptive Families

Though the numbers are sobering, there are many foster homes and foster parents who are, in many ways, a positive influence and transformative for youth who have had traumatic experiences. Healing from childhood adversity is a realistic possibility and requires time and attention. However, foster and adoptive families need the support of their government, team of professionals, and community resources to help break the cycle of trauma in which youth in care find themselves.

“…foster and adoptive families need the support of their government, team of professionals, and community resources to help break the cycle of trauma…”

Nonprofit organizations, such as the Annie E. Casey Foundation, compile evidence-based strategies to support families to care for children and youth who have had to leave their families of origin [4]. Child welfare agency strategies and procedures can enhance the capacity of families to care for vulnerable youth (Table 5.1).

Focusing on family relationships, supporting kinship care through financial support, education, and mentoring of extended relatives and friends can provide less disruption when a child requires removal and also enhances the pool of strong foster families. A child needs a loving, supportive, permanent home as soon as possible, and child welfare agencies should feel a sense of urgency to address the problems that threaten the parents’ ability to provide this or to find another stable and permanent alternative family.

Mentorship

A key factor that has been found to be significantly associated with better physical and mental health outcomes for youth transitioning out of care is mentorship. Mentored youth have improved outcomes in their transition to independence when they have had positive relationships to community professionals who, in a way, become the youth’s surrogate family [2]. Young people have a number of formal and informal relationships that can help support them throughout their adolescent and young adult years as they navigate the foster care system and transition out of foster care. Research with youth formerly in care shows that youth may be more receptive to professional mentors at critical transitions, such as the move into or out of foster care [1]. These may be key times to target the introduction of professional supports. Facilitating youth’s capacity to reach out and develop mentorship relationships may be an important life skill and should be integrated into transition planning for youth in care in their adolescent years.

Employment and Education Programs

Employment programs that provide paid training and work experience while engaging and providing mentorship in the work context are highly valuable for youth aging out of care. Trade programs or educational programs lasting 6–18 months may be more practical for youth who require a steady income and don’t have others that they can lean on for housing and food that would allow for 4-year or more college or university experience. Job training programs such as Job Corps have been shown to increase earnings and educational attainment for vulnerable youth, but it does require significant governmental investment to run [27]. Similarly, governmental-sponsored programs in British Columbia, such as Intersections Media or Plea’s Cue program for youth on probation, link youth with job placement under mentorship with positive feedback from youth and employers [13].

The Role of Healthcare Providers

How does a healthcare provider make a difference in the lives of these youth? Providers offer an important focus on health and well-being and can communicate those needs to others caring for the youth, including social workers, group home workers, foster parents, and counselors. Many pediatricians and adult providers are unfamiliar with the core issues affecting this demographic and may be intimidated by the social and systemic issues they face. However, this should not deter one from striving to provide the best possible care for these vulnerable youth, as there is much that providers have to contribute (Table 5.2) [30].

Providing a medical home that anticipates and responds to their specific needs, including medical, psychiatric, and neurodevelopmental, can improve outcomes for children and adolescents as well as newly fledged young adults [7]. Youth in care will almost universally need more frequent visits and close ongoing care coordination. For example, identifying concerns for a learning disability and advocating for appropriate psychoeducational and developmental assessments can transform a youth whose undiagnosed disability might otherwise be misinterpreted as a behavioral or disciplinary concern. Similarly, connection to appropriate trauma counseling and/or other indicated therapies can help avoid misdiagnosis of more severe psychiatric disorders, which can sometimes be the presentation of youth in crisis.

Some child protection jurisdictions have developed case management systems for youth in care, but the healthcare provider may need to advocate for connection to these services once a diagnosis is made. In other jurisdictions, care coordination is the responsibility of social workers who may have little health knowledge and are already overburdened with unrealistically high numbers of youth for case management. Many providers struggle with disrupted continuity of care and unpredictable placement changes that might impact treatment and follow-up plans.

Intervening early, prior to a youth aging out of care, yields the most benefit to the youth. Strong and positive attachments to communities are powerful determinants of better health outcomes [2, 9, 11]. Relationships between young people and service providers should be informed by an understanding of the youth’s resiliency and self-sufficiency.

Conclusions

Youth in care are a distinct segment of the homeless youth population, and they require a larger safety net focusing on prevention and stabilization during the critical stage when they transition out of care. This safety net must include educational opportunities, secure employment, housing options, and fiscal strategies, as well as longitudinal supports involving family when possible, welfare workers, and healthcare professionals. Similar to other young adults, former youth in care often require these second or third chances when becoming independent to allow for setbacks that are inherent to their journey into adulthood. In this way, emergencies and times of crisis can be made tolerable, and homelessness can hopefully be avoided.

Looking ahead to the next decade, resources developed to support a youth’s transition out of care should be transparent and easily accessible and facilitate a continuum of care from the services and care they received as children and adolescents. Vulnerable populations within this already high-risk population, including indigenous youth, visible minority youth, LGBT youth, and young women, will need dedicated consideration from all facets of the child welfare system. Healthcare providers can represent an important bridge during the transition out of care when the other professional supports, such as social workers, foster care, and group homes, fall away. In working toward effective advocacy for youth in care, we should remember that change needs to occur at all levels, whether it is involving the individual, family, school system, healthcare institutions, government housing and welfare system, or society at large.

References

Ahren KR, DuBois DL, Garrison M, Spencer R, Richardson LP, Lozano P. Qualitative exploration of relationships with important non-parental adults in the lives of youth in foster care. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2011;33(6):1012–23.

Ahrens KR, DuBois DL, Richardson LP, Fan MY, Lozano P. Youth in foster care with adult mentors during adolescence have improved outcomes. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):e246–52.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Helping foster and adoptive families cope with trauma [Internet]. Elk Grove Village: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2016. [cited 2019 May 16]. Available from: https://www.aap.org/en-us/Documents/hfca_foster_trauma_guide.pdf.

Annie E. Casey Foundation. Ten practices: a child welfare leader’s desk guide to building a high-performing agency [Internet]. Baltimore: The Annie E. Casey Foundation; 2015. [cited 2019 May 17]. Available from: https://www.aecf.org/resources/10-practices-part-one/.

Child Family Community Australia. Children in care [Internet]. Southbank: Australian Institute of Family Studies, Australian Government; 2018. [cited 2018 Dec 29]. Available from: https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/children-care.

Children’s Bureau. The AFCARS report: preliminary FY 2017 estimates as of August 10, 2018 – no. 25 [Internet]. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; 2018. [cited 2019 May 20]. Available from: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/afcarsreport25.pdf.

Christian CW, Schwarz DF. Child maltreatment and the transition to adult-based medical and mental health care. Pediatrics. 2011;127(1):139–45.

Collins ME, Clay C. Influencing policy for youth transitioning from care: defining problems, crafting solutions, and assessing politics. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2009;31(7):743–51.

Collins ME, Spencer R, Ward R. Supporting youth in the transition from foster care: formal and informal connections. Child Welfare. 2010;89(1):125–43.

Council on Foster Care, Adoption, and Kinship Care, Committee on Early Childhood. Health care of youth aging out of foster care. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):1170–3.

Creighton G, Shumay S, Moore E, Saewyc E. Capturing the wisdom and the resilience: how the Pinnacle program fosters connections for alternative high school students [Internet]. Vancouver: University of British Columbia; 2014. [cited 2019 May 17]. Available from: http://apsc-saravyc.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2018/04/Pinnacle-Program-Evaluation-Report-Nov-18-WEB.pdf.

Czapska A, Webb A, Taefi N. More than bricks & mortar: a rights-based strategy to prevent girl homelessness in Canada [Internet]. Vancouver: Justice for Girls; 2008. [cited 2019 May 16]. Available from: http://www.justiceforgirls.org/uploads/2/4/5/0/24509463/more_than_bricks_and_mortar.pdf.

Department of Justice. Evaluation of PLEA programs [Internet]. Ottawa: Department of Justice, Government of Canada; 2015. [cited 2019 May 11]. Available from: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/fund-fina/cj-jp/yj-jj/sum-som/r22.html.

Doyle JJ Jr. Child protection and child outcomes: measuring the effects of foster care. Am Econ Rev. 2007;97(5):1583–610.

Drapeau S, Saint-Jacques MC, Lépine R, Bégin G, Bernard M. Processes that contribute to resilience among youth in foster care. J Adolesc. 2007;30(6):977–99.

Dworsky A, Courtney M. Homelessness and the transition from foster care to adulthood. Child Welfare. 2009;88(4):23–56.

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–58.

Fowler PJ, Marcal KE, Zhang J, Day O, Landsverk J. Homelessness and aging out of foster care: a national comparison of child welfare-involved adolescents. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2017;77:27–33.

Havlicek J, Garcia A, Smith DC. Mental health and substance use disorders among foster youth transitioning to adulthood: past research and future directions. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2013;35(1):194–203.

Kovarikova J. Exploring youth outcomes after aging-out of care [Internet]. Toronto: Provincial Advocate for Children and Youth; 2017. [cited 2019 May 20]. Available from: https://www.provincialadvocate.on.ca/reports/advocacy-reports/report-exploring-youth-outcomes.pdf.

Park JM, Metraux S, Brodbar G, Culhane DP. Child welfare involvement among children in homeless families. Child Welfare. 2004;83(5):423–36.

Pasztor EM, Hollinger DS, Inkelas M, Halfon N. Health and mental health services for children in foster care. Child Welfare. 2006;85(1):33–57.

Rosenberg R, Kim Y. Aging out of foster care: homelessness, post-secondary education, and employment. J Pub Child Welfare. 2017;12(4):1–17.

Rutman D, Hubberstey C, Feduniw A. When youth age out of care – where to from there? [Internet]. Victoria: University of Victoria; 2007. [cited 2019 May 18]. Available from: https://www.uvic.ca/hsd/socialwork/assets/docs/research/WhenYouthAge2007.pdf.

Sawyer MG, Carbone JA, Searle AK, Robinson P. The mental health and wellbeing of children and adolescents in home-based foster care. Med J Aust. 2007;186(4):181–4.

Scannapieco M, Connell-Carrick K, Painter K. In their own words: challenges facing youth aging out of foster care. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2007;24(5):423–35.

Schochet PZ, Burghardt J, McConnell S. Does Job Corps work? Impact findings from the National Job Corps Study. Am Econ Rev. 2008;98(5):1864–86.

Sinha V, Kozlowski A. The structure of aboriginal child welfare in Canada. Int Indig Policy J. 2013;4(2):1–21.

Smith A, Stewart D, Poon C, Saewyc E. Fostering potential: the lives of BC youth with government care experience. Vancouver: McCreary Centre Society; 2011. [cited 2019 May 19]. Available from: https://www.mcs.bc.ca/pdf/fostering_potential_web.pdf.

Szilagyi MA, Rosen DS, Rubin D, Zlotnik S, Council on Foster Care, Adoption, and Kinship Care, Committee on Adolescence, et al. Health care issues for children and adolescents in foster care and kinship care. Pediatrics. 2015;136(4):e1142–66.

Turpel-Lafond ME. On their own: examining the needs of B.C. youth as they leave government care [Internet]. Victoria: Representative for Children and Youth; 2014. [cited 2019 May 16]. Available from: http://www.rcybc.ca/sites/default/files/documents/pdf/reports_publications/rcy_on_their_own.pdf.

Zlotnick C, Tam TW, Soman LA. Life course outcomes on mental and physical health: the impact of foster care on adulthood. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(3):534–40.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Wang, J., Moore, E. (2020). Youth in Care: A Very High-Risk Population for Homelessness. In: Warf, C., Charles, G. (eds) Clinical Care for Homeless, Runaway and Refugee Youth. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-40675-2_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-40675-2_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-40674-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-40675-2

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)