Abstract

Secondary school food teachers have faced a period of unprecedented change in England. With recent fundamental changes to the National Curriculum (NC) for design and technology (D&T) and for food technology, food education is going through a crisis in secondary schools.

These changes are in the context of the government’s new school accountability measures—Progress 8 and Attainment 8 (Department for Education, 2016)—and the privileging of academic subjects in the curriculum through the introduction of the English baccalaureate. This chapter will describe each of these features and use the research findings from a national questionnaire by the authors to assess what the general situation is across schools in England.

National questionnaire: current views on food teaching (Appendix 1)

The authors distributed a national questionnaire to as many education contacts as possible. This was to gather as wide a picture of the current climate for food education provision. Nineteen responses were received from schools spread out across the UK. It investigated what provision there is at Key Stage 3 (KS3) (pupils aged 11–14 years in food) and the available options for pupils at Key Stage 4 (KS4) (pupils aged 14–16 years) and what is the uptake of these opportunities by pupils. The questionnaire attempted to ascertain what options there are available to students at Key Stage 5 (KS5) (pupils aged 16–18 years) and if there is variability for such courses across England. This research also hoped to highlight changes in lesson timetabling for such courses by Key Stage and how this would impact upon the range of practical versus theory teaching strategies that are possible.

Case studies: in-depth view on food teaching (Appendix 2)

Three case studies provided by food teachers from secondary schools around the country in London, Cornwall and Derby were also used to more deeply explore and understand ‘the state of teaching food’ in secondary schools in England. The case studies particularly highlighted the changes in uptake of such courses across the secondary school phases.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Secondary education

- England

- General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE)

- National Curriculum (NC)

- Food education

How Did Food Education Begin in English Schools?

Historically food has been in the English school curriculum since the mid-nineteenth century. Its aim was to teach cooking skills to girls so they could provide for their families and to prepare them for domestic service (Lawson, 2013). During the twentieth century, the subject developed with the aim of being to prepare nutritious and affordable family meals.

In 1926, the Howden report stated that the ‘general aim should be to provide practical instruction in the choice and preparation of the food required for a simple wholesome diet, with due regard to home conditions and the need for economy’ (Central Advisory Council for Education (CACE), 1926, p. 235). Grammar schools taught girls domestic science with greater emphasis on nutrition and science. In 1945, following the Second World War, the new secondary modern schools for pupils that had not passed the entrance examination to grammar schools thought that the health of the nation was vital and those girls should learn to cook (Rutland & Barlex, 2006). There was little change until the Newsome report (CACE, 1963, p. 389) found that ‘housecraft and needlework justified their place in the curriculum for most girls’. This was suitable at a time in society when most girls went on to become homemakers. In 1975, the establishment of the Sex Discrimination Act resulted in more boys being encouraged to enrol in food-related subjects, and with the advent of food technology, more boys did engage with the subject, but still by 2010, this was still only 36% (Design and Technology Association (DATA), 2010).

By the mid-1980s, domestic science had evolved into home economics (HE), but broadly speaking it still held a strong focus on preparing nutritious and cost-effective meals and was studied predominantly by girls. In 1990, Technology was introduced with the advent of the NC (Department for Education and Schools (DES), 1990), and HE was retained within the D&T section of technology and transformed into food technology. Food education changed, moving away from cooking and nutrition, and became more broadly based around industrial practice and scientific and technological principles. The British Nutrition Foundation (BNF) welcomed this change in the curriculum and thought that food technology would teach scientific principles to pupils in a clearer and more easily communicable manner. With the foundation of the ‘Healthy Schools’ initiative in 1999 there was now focus predominantly aimed to improve not only food education but also the wider issue of all foods available to all children in school (Department of Health (DoH) & Department for Children, Schools / Families (DCSF), 2007).

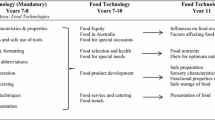

The 1990 Education Act introduced Technology, which included D&T and information technology (IT). Food was included within D&T. With the following N/C revision in 1995, Technology became D&T and IT, and the two were considered separate subjects (Department for Education/Welsh Office (DFE/WO), 1995). Many teachers found themselves at odds with the teaching of food design within D&T. There was little training for previous HE teachers, and many felt alienated from a curriculum that seemed to have little reference to food and contained such words as designing, artefacts, systems and mechanisms (Rutland & Barlex, 2006). Less ‘practical making’ and more designing tasks where pupils ‘drew’ food meant that the subject lost status and direction. Rutland and Barlex (2006) argued though that designing in food was very different to that of other D&T areas. It involved brainstorming, questionnaires, product attribute analysis and modelling of food ingredients. Owen Jackson (2007) went on further to say that food design related more to product development and involved working with actual food ingredients rather than simply drawing them. Food technology remained within D&T through changes in the N/C in 1995, 1999 and 2007, although it has always had a rather chequered history, as we will go on to discuss in the next section.

Recent History 1995: To Present Day

Since one of the authors began a career in teaching in D&T in 1998, there have been some very fundamental changes to the subject, most significantly in respect to changes to food technology and the methodology of teaching the subject. Initially, there was a compulsion for every pupil in England to follow a technology subject at General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE), and food technology was a very popular choice, although more so by girls than boys:

Though, food technology still suffered from being a subject perceived as being ‘for girls’ and as a subject with more vocational relevance than academic

(Owen-Jackson, 2013, p. 106).

The Specialist Schools Programme (1993) introduced the concept of ‘Technology College’ status, and technology played an important part in the politics of education (Gove, 2010). The government awarded this status; however, in 2004, although there were many technology status schools, the government decided to remove the requirement for pupils to study a GCSE in Technology, and many teachers felt this was the start of the slow decline of the subject. Personal experience of this was going from teaching four classes of GCSE food technology to just one within 1 year of this change. This is a similar situation to that of the London case study school as below:

Our school became a specialist school for Design and Technology in 2009, and remained so until government funding ceased in April 2011. During the time of being a specialist school all students were required to take a D&T subject for GCSE. For food, options of choosing Food Technology or Catering were available. During this time the school had approximately 100 students taking a food focused GCSE. With the advent of the withdrawal of specialist status, students were no longer required to take a D&T GCSE option. The school continued to offer both GCSE options and an average of 40 students took one. From 2014, only food technology was an option choice, before its removal and change to Food Preparation and Nutrition (In-depth view on Food Teaching - London Case Study School, 2018).

However, the government continued to look at societal health problems through the ‘Health of the Nation’ white paper (Department of Health, 1992) and felt that there was simply not enough quality food education happening in many schools in England. In fact, one in five children who joined primary school in 2015 were obese or overweight (Huffington Post UK, 2015). However, some good news showed that the proportion of teenagers having chips for lunch plummeted from 43% to 7% (Children’s Food Trust, 2015).

Many charitable organisations have supported food education in England. These include Jamie’s School Dinners, The School Fruit and Veg scheme, the Every Child Matters agenda, Let’s get Cooking Campaign, the Healthy Schools initiative, the Soil Association, Food for Life, Jamie Oliver’s kitchen garden project, Change for Life, the Countryside Classroom, the British Nutrition Foundation and the Food Teachers Centre. Why then is it that most of these are charitable organisations with no funding from the government, and how has this impacted on food in the school curriculum?

In 2008, the current Secretary for Education, Ed Balls, brought in the ‘Licence to Cook’ (DfE Licence to Cook programme, 2007–2011) programme. This initiative intended to give all pupils at least 8 h of cooking each school year. The main issue here was that where there was excellent food technology teaching taking place, in some cases it was replaced by the ‘Licence to Cook’ programme, which was by far less scientific and led to an impoverished learning experience for pupils. Rutland (2008) reviewed the scheme and deemed that it led to issues with progression from KS3 to KS4 (11–16 years). Food technology began to lose its focus, and as Lawson stated there was a need to ‘make food technology more relevant and challenging for pupils in the 21st Century’ (2013, p. 101). There was a need in Year 7 (pupils aged 11 years) to capture their interest and imagination and ensure there was no repetition of their previous experiences in primary school. Their learning should build on existing knowledge and deepen their understanding of how nutritional properties of food contributed to their health and well-being, engaging them fully.

Fundamentally, the DfE’s School Food Plan (Department for Education (DfE), 2013) called for a whole school food approach/culture, recognising that neither balanced school meals nor food education alone was sufficient to enable children to live well and eat healthily.

The Revised National Curriculum in England: D&T Programmes of Study (PoS) (DfE, 2013)

The revised D&T PoS (DfE, 2013) has a separate ‘Cooking and Nutrition’ section as a compulsory part within the D&T curriculum for pupils aged 5–14 years, and it has had a major impact on food education in England. However, it is important to note that food/ingredients remained as a material in the D&T PoS for KS1–3 (5–16 years).

Teaching pupils how to cook and apply the principles of nutrition and healthy eating is the main aspect of the new PoS. Learning how to cook is a crucial life skill that enables pupils to feed themselves and others affordably and well, now and in later life. They should be taught to:

-

Understand and apply the principles of nutrition and health.

-

Cook a repertoire of predominantly savoury dishes so that they are able to feed themselves and others a healthy and varied diet.

-

Become competent in a range of cooking techniques (e.g. selecting and preparing ingredients; using utensils and electrical equipment; applying heat in different ways; using awareness of taste, texture and smell to decide how to season dishes and combine ingredients; adapting and using their own recipes).

-

Understand the source, seasonality and characteristics of a broad range of ingredients.

The Impact of Changes in the English National Curriculum

In 2017, one of the authors having taken part in an examination board presentation for the new D&T GCSE found it very disappointing that there was no mention of food education and there was no information regarding it forthcoming from the session. It was almost as if the examination board had completely disregarded the link between D&T and food.

The most recent accelerated decline in D&T numbers links, in part, to the narrow curriculum focus due to the high status of the English baccalaureate (EBacc). The government introduced the EBacc in 2010, and the proportion of pupils entering into the EBacc almost doubled in recent years, rising from 22% in 2010 to 39% in 2014 (DFE, 2015c):

We will require secondary school pupils to take GCSEs in English, maths, science, a language and history or geography, with the Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted) unable to award its highest ratings to schools that refuse to teach these core subjects (Conservative Party Manifesto, 2015).

In terms of initial teacher education (ITE), it increased the shortages of those training in EBacc subjects as the government had previously restricted the number who could train in these subjects. This led to a large rise in the bursary payments for those subjects to attract more candidates into teaching. Lower numbers were then allowed to train in non-EBacc subjects combined with a withdrawal of the bursary altogether for the majority of subjects including D&T, art and design, music, drama and physical education (PE).

Pupils study the ‘core’ academic subjects of English, mathematics, science, a modern foreign language (MFL) and either geography or history as a humanities subject. They are given far fewer options at GCSE level as all the remaining ‘creative subjects’ are collected in one or two option blocks, allowing little choice for pupils (Turner, 2017). ‘The likelihood was that the arts, technology, physical education and religious studies would be lost to accommodate compulsory history and geography’ (Schools, Students and Teachers network (SSAT), 2015). The government’s ambition is to see 90% of GCSE pupils choosing the EBacc subject combination by 2025 (DfE, 2015c), and this will surely have an ongoing impact for the uptake of D&T and especially food in the coming years:

The ability of students being encouraged to take the subject has declined as higher pathway students have more limited option choices therefore we cannot compete against languages and the triple science pathway

(Current views on Food Teaching, Teacher B 2018a)

Food is a popular subject at KS3 however many do not choose it for GCSE, as they are limited by the number of subjects that they can choose.

(Current views on Food Teaching, Teacher C 2018a)

The additional impacts on food teaching related to the time allocation for lessons:

When lessons are only fifty-five minutes long, there is little time for practical of any great skill, importance and that is scientifically nutritionally sound

(Current views on Food Teaching, Teacher D 2018a).

In my first school food teaching reduced to one hour per week. This was then reduced to fifty minutes, a nightmare for food teaching’ In my current school students get 18 weeks of cooking and nutrition through the whole of their secondary school education – I do not feel this is enough

(In-depth view on Food Teaching, Cornwall case study school 2018b)

The British Nutrition Foundation (BNF) felt that ‘there is still a long way to go and in many schools nationwide, the picture of food education gives cause for concern’ (BNF, 2017).

The AKO Foundation (a registered charity whose primary function is to award grants to projects that seek to improve education) commissioned the Fell report (2017). In a combined study by the Jamie Oliver Food Foundation, the BNF, the Food Teachers Centre and the University of Sheffield, they undertook a comprehensive review of the state of food education in England.

In the report (2017, p. 29), questions posed include ‘how well are pupils enabled under the new NC to develop key knowledge and skills through their food education’ and ‘are they able to put this knowledge learnt into practice’. It was clear from the report that although secondary pupils were able to describe the principles of a healthy diet, they experienced challenges in applying this learning. There is further evidence put forward in the report (2017, p. 44) that for curriculum-based food education to have a maximum impact, it needs embedding within the wider school food culture. Although some schools adopt a whole school approach from the teaching of the subject in D&T through to the school canteen and breakfast/dinner clubs, this is all too rare a situation and there is little or no ‘joined-up thinking’ in schools. ‘Experiential learning can support learning outcomes’ (2017, p. 37) where pupils who are taught the essentials of healthy eating in the classroom are then able to put this in to practice through ingredient and recipe changes in class, lunch choices or snacks between lessons.

According to the Fell report (2017), there is a great deal of variability in the delivery of food and nutrition education, with really stark differences between those schools delivering really robust food education and those who are struggling due to a lack of time, resources and support. Food teachers report that a lack of training time, curriculum class size, budgets and facilities has a significant impact on both the quality and quantity of food lessons (Current views on Food Teaching, Teacher D2018a).

Figures from the Fell report show that 50% of secondary teachers reported that pupils have between 11 h and 20 h per year at KS3, with nearly 16% reporting pupils have less than 10 h (2017, p. 39). Time both in terms of total time allocation for each food lesson has hampered teachers’ ability to deliver not only the breadth of the curriculum but also to an adequate depth:

Time is a massive factor on the food that can be prepared and cooked in lessons. Hour lessons are ridiculous, stressful and constraining

(Current views on Food Teaching, Teacher E 2018a)

As can be seen from Fig. 4.1, 66% of teachers felt that there was insufficient time for adequate food teaching in schools.

Time as a barrier to delivering high-quality food education (2017, Fell Report, p. 39)

Current Views on Food Teaching Results from Author’s National Questionnaire ‘Current Views on Food Teaching’ (2018a) (Appendix 1), Case Study Schools’ ‘In-Depth View on Food Teaching’ (2018b) (Appendix 2) and the Fell Report (2017)

From the questionnaire responses (19), there appears to be even greater disparity in schools with some pupils receiving 12 h or less but others as many as 55 h provision per year for KS3 (11–14 years) and up to 100 h for KS4 (14–16 years), which is a huge variance and does nothing to instil confidence in the quality of provision. Anecdotally, teachers spoken to (whilst on visits in school) have expressed the opinion that where their head teacher has understood the value of the subject, the timetabled hours and budgets have been higher and there has been less predominance on the EBacc subjects. Where this allegiance to the subject is lacking, the opposite outcome is seen (Current views on Food Teaching, 2018a).

From the figures in the questionnaire, there would appear to be a good ratio of practical versus theory with 71% of teachers saying pupils at KS3 (11–14 years) carried out practical tasks once a week and 29% only every 2 weeks (Current views on Food Teaching, 2018a).

Budgets cause a huge amount of stress for senior managers, and respondents felt this was a huge challenge to delivering high-quality food education. Concerns raised included not being able to replace broken equipment, repairing unsafe teaching rooms or providing ingredients for pupils. More than 65% of teachers said their budget had decreased over the last 3 years, and 47% said it was to reduce even further. Less than 50% said they had sufficient facilities or resources to deliver the curriculum to a satisfactory standard (Fell Report, 2017).

Class size is a key factor in the challenge of food education: ‘you cannot assess a class of 26 pupils all cooking at the same time’ (Current views on Food Teaching, Teacher F 2018a). In more than 50% of schools, the ratio of cookers to pupils was 1:3 or less, often with not all the cookers working at one time (Fell Report, 2017). The questionnaire showed that in 40% of classes, there were more than 30 pupils at KS3, which is a real concern, especially for health and safety, and this would ultimately affect the quality of experience for the pupils and perhaps deter them from choosing the subject at GCSE (Current views on Food Teaching, 2018a).

In addition, 92% of secondary school teachers felt that food should be taught by specialist teachers, and many reported this was not the case (and given as a reason for the subject being removed from their school curriculum), and in some instances there were no food specialists at all delivering food education. Many teachers aspire to having food education as having higher status and want it to be valued as an integral part of the curriculum, instead of it being looked at as a lesser subject with little importance.

The New GCSE Food Preparation and Nutrition for KS4 Pupils (Aged 14–16 Years)

A key development has been at KS4 (14–16 years) where food technology as a material area within GCSE D&T courses was replaced with a new GCSE qualification food preparation and nutrition (DfE, 2013). The change from food technology to ‘cooking and nutrition’ was unacceptable for the new GCSE however, and it changed to ‘food preparation and nutrition’. This reflected the feedback from all quarters on the use of the word ‘cooking’ within the title whilst still being clear that the qualification would teach students practical cooking skills.

There was a delay in the introduction of the new D&T GCSE until September 2017, which was due to the vociferous response from those in education who identified the flaws in the new specification. However, the new food preparation and nutrition GCSE, with first examination in 2018, began in 2016 (DATA, 2015). The DFE (2015a, p. 19) felt ‘this new GCSE is a general qualification which will enable progression to a wide range of further qualifications and careers in the food industry’.

In response to this, in the author’s questionnaire, 71% of the teachers felt that there was insufficient provision at KS4 and 87% insufficient at KS5 (Current views on Food Teaching, 2018a).

If we look at the national figures in Fig. 4.2 for food technology GCSE entries over the last 5 years, there has been a steady decline in the uptake numbers for food technology from 44,642 in 2013 to 29,773 in 2017. This is a percentage drop of 33.31%, which is alarming to say the least (DATA News, 2015).

However looking at the Joint Council for Qualifications (JCQ) (2018) data, it shows that 49,748 pupils sat the new GCSE food preparation and nutrition qualification in 2018, which would appear to be a large increase. This figure though must be taken in relation to other qualifications in food that were no longer available to pupils, typical example in Fig. 4.3.

Concurrently, if we look at the national figures in Fig. 4.3 for the hospitality and catering numbers during the same period, these are the only vocational food qualifications compiled in this manner to compare with the GCSE. There is also a significant drop between 2013 and 2017 from 868 to 338 entries. This is a percentage drop of 61%, which is even more alarming. Interesting in 2017, although the figures were lower than the previous year, the percentage of pupils completing a vocational food qualification rose to 35% from the previous year of 22% of the total entries. This could indicate that a number of schools were moving away from the new GCSE in food preparation and nutrition and undertaking hospitality and catering instead, perhaps due to the higher level of science and maths in the new GCSE.

The government reformulated GCSEs to make them more in line with international standards (Food Teachers Centre, 2018). In 2018, the first cohort of the new GCSE food preparation and nutrition went through. The Office for Qualification and Examinations Regulation (Ofqual) and the examination boards ensured that results compared fairly to those of previous years, so the candidates were not disadvantaged. Indeed the overall outcomes were 62.3% at grades 4–9 (equivalent to A–C) with 70% of all girls and 48% of all boys attaining grades 4–9. This is the same as the previous years’ results of 62.3%, taken as an average across all examination boards.

With the new GCSE being harder in nature, with a higher percentage of scientific and mathematical output along with more in-depth nutritional knowledge and more complex practical skills, there is concern that those lower ability pupils will have no alternative options. Food has always been very successful as its practical nature can motivate, inspire and provide success for pupils with special educational needs. This is especially pertinent now as Ofqual (2018) is not approving entry-level qualifications and school leaders are opting for only those subjects that fall within Progress 8 assessment criteria:

The subject is popular but can sometimes be under pressure as it is an academic school and this is not always viewed as an academic subject despite the new scientific content

(In-depth view on Food Teaching - Derby Case Study School, 2018b)

In summary, there is currently no longer a wide range of choices for food courses at GCSE level. Those available currently (at the time of writing) include:

-

GCSE food preparation and nutrition from exam boards:

-

The Assessment and Qualifications Alliance (AQA)

-

The Welsh Joint Education Committee (WJEC)—branded EDUQAS

-

The Oxford, Cambridge and RSA Examinations Board (OCR)

-

-

WJEC hospitality and catering at Level 1 or 2 (Level 2 is equivalent to GCSE)

-

City and Guilds Level 2 Award in Cookery and Service

-

WJEC Food Science and Nutrition Certificate and Diploma Level 3 (equivalent to A Level as no A Level available)

Summary of the Specifications for the New GCSE Food Preparation and Nutrition

When introducing the GCSE, each examination board refers to the development of cooking skills and the ability to make informed choices. The specifications have clear similarities. There is an emphasis on nutrition and health, and students develop their understanding of macronutrients, micronutrients, energy needs, nutritional analysis, diets for specific needs and making informed choices to limit major diet-related health risks. A second key area is food science, through which students develop their understanding of the functional and chemical properties of ingredients as well as the effect of cooking on sensory characteristics. There is an emphasis on food safety as a requirement to learn about the principles of food safety as well as food spoilage and contamination. Each specification includes sections related to food provenance and choice. The WJEC and OCR specifications are more explicit with regard to ingredients that should be studied, both making it clear that it is the major commodity foods that should be studied. Food preparation skills are fundamental to all the specifications. Each is specific about what skills and techniques are to be included, and there are clear similarities between these. There is also far greater emphasis on the development of ‘food preparation skills’ which has caused a deficit in the area of developing new food products and use of emerging ingredients and techniques compared to the previous food technology GCSE:

However, the time scales suggested by the exam board are very difficult to achieve in sufficient detail. As we do not have longer double lessons, preparing for the new three-hour practical exam is also more difficult as the students are not used to working for this length of time. Mock exams are scheduled for the summer term in Year 10 to give them this experience at least once (‘in-depth view on Food Teaching - Derby Case Study School, 2018b).

The overall structure of assessment is the same across all the examination boards. Each has a written paper that is worth 50% of the grade. Each has two non-examined assessment (NEA) tasks. The first of these worth 15% is a food investigation task. This requires students to demonstrate their understanding of the functional and chemical properties of ingredients. The examination board sets the focus, where students are required to plan, carry out and evaluate practical investigations. There is some variation in the time allocation from 8 h to 10 h. The examination boards also set the food preparation task and this is worth 35%. The task requires students to demonstrate their ability to plan, cook and prepare a selection of dishes. The time allocation varies from 12 h to 20 h. This also includes a 3-h practical exam in which students are required to make three dishes.

The written papers vary slightly in structure. The AQA exam is in two sections: the first section includes only multiple-choice questions. The second section includes five questions with a number of sub-questions, some of which require students to give extended answers. The WJEC exam paper is also in two sections: the first section typically includes questions based on visual stimuli, for example, images of different stages of making a recipe with the questions based on the recipe. The second section includes a range of question styles, some of which require extended answers. The OCR examination paper is not in sections and includes a range of questions. As with the other boards, some of these require extended answers:

The new GCSE food preparation and nutrition course is very complex. I do feel the nutrition and dietary related disease aspect is superb. The intensive food science section I feel goes into too much depth and should be an aspect to be taught at ‘A’ level

(In-depth view on Food Teaching - Cornwall Case study School, 2018b).

Examination Courses for KS5 Pupils (Aged 16–18 Years)

At KS5 (pupils 16–18 years), the opportunity to take General Certificate of Education (GCE) A Level Food Technology has been removed. Only some vocational qualifications for this now exist:

At KS5, all U6 students take part in a life skills programme with a survival cookery element. We are now offering WJEC Level 3 at the Certificate level to a small group of 6th form students run as part of the enrichment programme.

(In-depth view on Food Teaching - Derby Case Study School, 2018b)

It is possible for schools to offer City and Guilds Level 1 and 2 courses in hospitality and catering. However, it is not feasible for most schools as there is a minimum requirement for a centre to have at least 100 students studying for City and Guilds qualifications. Only one of the schools who responded to the questionnaire commented they even had contacts with or used a local further education (FE) college to deliver these or similar qualifications (Current views on Food Teaching, 2018a).

One qualification that has remained accredited is the business and technology education Business and Technology Education Council (BTEC), specialist work-related qualification, Level 1 home cooking skills. However, this course does not have performance points. The course focuses on the development of practical cooking skills, and assessment takes place through a portfolio of work.

Another qualification with an uncertain future is the NCFE Level 1 and 2 V Certs in Food and Cookery (NFCE, 2018). These courses are complimentary technical awards and the vocational equivalent of GCSE qualifications. They are for 14–16 year olds who are interested in gaining experience of using different cooking techniques and methods to enable them to use these within further education or apprenticeships. It provides them with a basic understanding of the skills required for a career in food. These qualifications are, in the main, assessed internally, through portfolio work. They are currently DfE approved for Progress 8 and performance tables but will not be past March 2019, when the qualification will expire. Those schools offering the course after this date will not be able to use the results towards their performance tables, hence the uncertainty (Qualhub, 2018).

The Technical awards, which intended to provide a more practical approach to learning about food and were available as Level 1 and 2 awards, are also no longer available. Having not gained government approval, the examination boards removed them, much to the frustration of schools who had already started teaching the syllabus.

Therefore, in terms of a comparison to other subjects, food has only 5 qualifications, science has 49 and performing arts has as many as 62, and even D&T and engineering have 38 (Food teachers Centre, 2018). The majority of schools in responding to the questionnaire indicated that they use AQA (55%) as their preferred board with the Welsh Joint Education Committee (WJEC) and Edexcel second (20%) and National Council for Further Education (NCFE) (13%).

Expertise of the Food Teacher

To qualify as a secondary teacher, student teachers undertake a degree in the related subject they wish to teach. However, this is not always the case for food teachers who may have a degree in a related D&T subject such as product design or textiles, with food being their second subject. According to the BNF (2017), only one-fifth of secondary food teachers had an A Level in food technology, which has to be of concern.

The Department of Education (DfE, 2016) reported that there were only 4500 food teachers across the age range 5–16 years compared to 5300 in 2011 (this compares to 34,100 English teachers in 2016). For the same period for Key Stage 5 (16–18 years), this reduced further to 600:

‘There is only myself who teaches KS4 and KS3. Non-specialists teach some of KS3, from history and art. This does not work very well, and I have to pick up all the missed skills and knowledge not provided in the previous year’.

(In-depth view on Food Teaching - Cornwall Case study School, 2018b).

We are considering removing Food from the curriculum, as we have no specialist teachers and the last year group taking GCSE is Year 11 (aged 16 years). We have excellent facilities and students are keen but we have no way of delivering high quality lessons

(Current views on Food Teaching - Teacher F, 2018a).

In the Public Health England (PHE) and BNF report on ‘Food Teaching in School: A Framework of Knowledge and Skills’ (2015), a set of standards was established with the expectations and requirements for qualified food teachers, in order to raise the profile of food education in schools. This went on to become part of the Ofsted common inspection framework and aimed ‘to promote a whole school “Food” ethos to raise awareness of the integral part food and the whole school approach plays in children’s health, well-being and attainment’ (PHE, 2015). This should surely improve the situation for the teaching of food in schools.

Conclusion

It may appear from reading this chapter that there is little to be satisfied with food education in England and that the subject is suffering both a crisis of confidence and more importantly existence. However, with so many charitable organisations and dedicated teachers and pupils wanting to study food, it must surely improve with the raised profile of the subject. There are ‘stalwarts’ who truly value its place in the curriculum, and we must rely on them to keep the subject flourishing and demonstrate how relevant it is in modern society.

There is currently little choice for those students wishing to take food at GCSE level, but with Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted) now venturing to say that the school curriculum has become too constricted and not ‘rich and diverse enough’, there is an optimism amongst those in the creative subject areas that things are about to change. Schools that are predominantly offering EBACC subjects to the preponderance of others will find they will not considered ‘outstanding’.

A more positive aspect seen is with 49,748 pupils having sat the new GCSE food and nutrition examinations in 2018. Total numbers are therefore up from the previous years’ examination cohorts, even if we consider the lack of other options available to pupils; it is still an overall increase.

In the London Case Study School and other schools (backed up by anecdotal evidence on visits), some are venturing down the route of considering the GCSE as a 5-year examination pathway. The Schemes of Learning (SoL) being developed are to reflect and allow better progression towards GCSE specifications. The introduction of more food science by the explanation of food processes, in more depth, and the inclusion of class investigations are taking place in Year 7 lessons. The depth of knowledge they require is built from a stronger foundation with more emphasis placed on this through KS3 (11–14 years), leading more satisfactorily onto the KS4 (14–16 years) specifications.

Many schools have also undertaken to start the GCSE classes with pupils in Year 9, deciding that taking more time to cover the specifications over the 3 rather than 2 years will allow pupils to build the depth of knowledge and understanding they require to realise success in their examination outcomes:

‘Food is very popular at our school, with 5 KS4 groups and KS5 groups also. All pupils study food at KS3. Our results are excellent and behaviour is good in lessons.’ (Current views on Food Teaching - Teacher G, 2018a)

References

AKO Foundation. (2017). The food education learning landscape report (Fell Report). The Jamie Oliver Foundation. AKO.

British Nutrition Foundation (BNF). (2017). Food teaching in schools: A framework of knowledge and skills. London: British Nutrition Foundation. Retrieved November 28, 2012, from https://www.nutrition.org.uk/foodinschools/competences/foodteachingframework.html.

Central Advisory Council for Education (CACE). (1926). The education of the adolescent (Howden Report). London: HMSO.

Central Advisory Council for Education (CACE). (1963). Half our future (Newsome Report). London: HMSO.

Children’s Food Trust. (2015). Retrieved November 23, 2018, from https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/food-education-initiatives-childhood-obesity_UK

Conservative Party Manifesto. (2015). Retrieved November 18, 2018, from http://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/wmatrix/ukmanifestos2015/localpdf/Conservatives.pdf

Design and Technology Association (DATA). (2010). News – Exam results. Retrieved November 22, 2018, from https://www.data.org.uk/search/?q=exam%20results%20in%202010

Design and Technology Association (DATA). (2015). Is there a future for Food Education. Retrieved November 22, 2018, from https://ojs.lboro.ac.uk/DTT/article/view/1356/1316

Design and Technology Association (DATA) News. (2015). Retrieved November 22, 2018, from https://www.data.org.uk/news/clarifying-the-position-of-food-within-the-gcse-review/

Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF) & Department of Health (DoH). (2007). The children’s plan: Building brighter futures Her Majesty’s stationary office. Norwich: HMSO.

Department for Education (DfE). (2013). The school food plan.

Department for Education and Schools (DES). (1990). Technology in the National curriculum. London: HMSO.

Department for Education/Welsh Office (DfE/WO). (1995). Design and technology in the National curriculum. London: HMSO.

Department of Health (DoH). (1992). The health of the nation – A strategy for health in England. London: HMSO.

Department of Health (DoH) & Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF). (2007). The healthy schools programme. London: Crown.

DfE. (2013). National Curriculum in England: Design and technology programmes of study, Retrieved November 24, 2018, from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-design-and-technology-programmes-of-study/national-curriculum-in-england-design-and-technology-programmes-of-study

DfE. (2015a). Food preparation and nutrition. GCSE subject content. London: Department for Education. Retrieved November 25, 2018, from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/405328/Food_ preparation_and_nutrition_180215.pdf

DfE. (2015c). Guidance, English Baccalaureate. Retrieved November 30, 2018, from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/english-baccalaureate-ebacc/english-baccalaureate-ebacc

DfE. (2016). Progress 8 – How Progress 8 and Attainment 8 measures are calculated, (PHE). Retrieved August 01, 2019, from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/561021/Progress_8_and_Attainment_8_how_measures_are_calculated.pdf

DfE Licence to Cook programme. (2007–2011). Retrieved November 24, 2018, from https://www.foodafactoflife.org.uk/11-14-years/cooking/licence-to-cook/

Food Teachers Centre. (2018). Retrieved December 12, 2018, from https://foodteacherscentre.co.uk/blog/

Gove, M. (2010). Letter to SSAT regarding Specialist School status. Retrieved November 30, 2018, from http://www.politics.co.uk/reference/specialist-schools

Huffington post. (2015). Retrieved November 26, 2018, from https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2015/11/26/regional-differences-in-childhood-obesity-rates-report_n_8655108.html

Joint Council for Qualifications (JCA). (2018). Retrieved December 12, 2018, from https://www.jcq.org.uk/examination-results/gcses/2018

Lawson, S. (2013). In G. Owen-Jackson (Ed.), Debates in design and technology education. Oxon: Routledge.

NCFE. (2018). Retrieved November 26, 2018, from https://www.ncfe.org.uk/schools/subject-areas/food-and-cookery

Ofqual. (2018). GCSE outcomes in England. Retrieved December 12, 2018, from https://analytics.ofqual.gov.uk/apps/2018/GCSE/Outcomes/

Owen-Jackson, G. (2007). Practical guide to teaching design and technology in the secondary school. London: Routledge.

Owen-Jackson, G. (Ed.). (2013). Debates in design and technology education. Oxon: Routledge.

Public Health England (PHE). (2015). Food teaching in secondary Schools: A framework of knowledge and skills. Retrieved November 30, 2018, from https://www.nutrition.org.uk/attachments/article/869/Food%20teaching%20in%20secondary%20schools.pdf

Qualhub. (2018). Retrieved November 26, 2018, from https://www.qualhub.co.uk/qualification-search/qualification-detail/ncfe-level-2-certificate-in-food-and-cookery-4434

Rutland, M. (2008). Licence to cook: The death knell for food technology DATA international research conference proceedings. Wellesbourne: DATA.

Rutland, M., & Barlex, D. (2006). Developing a conceptual framework for auditing design decisions in food technology: The potential impact on initial teacher education (ITE) and classroom practice. In E. Norman & D. Spendlove (Eds.), The design and technology international research conference proceedings. Wellesbourne: DATA.

Schools, Students and Teachers network (SSAT). (2015). EBacc for all? SSAT. Retrieved November 28, 2018, from http://www.expansiveeducation.net/Resources/Documents/EBacc%20for%20all%20-%20SSAT%20Report.pdf

Seabrook, R., (2018a) National questionnaire: current viwes on food teaching (Appendix 1).

Seabrook, R., (2018b) Case studies: in-depth view on food teaching (Appendix 2) Cornwall, London and Derby.

Turner, C. (2017). Design and technology GCSE axed from nearly half of schools, survey finds; Telegraph. Retrieved November 30, 2018, from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/education/2017/03/10/design-technology-gcse-axed-nearly-half-schools-survey-finds

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Case Study Questions

-

1.

Historically what food teaching was there at KS3, prior to the new National Curriculum?

-

What sort of food were cooked?

-

Any science?

-

How many hours p/y?

-

Specialist food teachers?

-

-

2.

What options were available at KS4?

-

Vocational?

-

Diploma?

-

GCSE?

-

Catering?

-

Level1 or 2?

-

Take up at GCSE level?

-

What option block?

-

What were the outcomes?

-

-

3.

Anything at KS5? Please give examples.

-

4.

Exam boards chosen?

-

5.

Since new N/C what is taught now at KS3?

-

How many hours?

-

Sorts of dishes?

-

How many hours p/y?

-

Any science?

-

Any nutrition?

-

Food specialists?

-

-

6.

Since new N/C what is taught now at KS4?

-

What is the take up now at GCSE level?

-

What options are available?

-

What option block?

-

Food specialists?

-

How many staff?

-

-

7.

Anything at KS5? Please give examples.

-

8.

Do pupils pay for ingredients or does school provide?

-

At KS3?

-

At KS4?

-

-

9.

Do you have technicians?

-

10.

Examination boards chosen now?

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Seabrook, R., Grafham, V. (2020). What Is the Current State of Play for Food Education in English Secondary Schools?. In: Rutland, M., Turner, A. (eds) Food Education and Food Technology in School Curricula. Contemporary Issues in Technology Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39339-7_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39339-7_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-39338-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-39339-7

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)