Abstract

Theoretical conceptualizations of prejudice have shifted dramatically over the past century, with prejudice first conceptualized as a natural and normative – and often overtly expressed – response of members of dominant groups to the perceived inferiority of members of nondominant groups. More recently, prejudice has been conceptualized as reflecting those attitudinal and affective responses of dominant groups toward nondominant groups that are subtle and occur outside of awareness as a function of unconscious processes. Shifts in the conceptualization of prejudice have occurred in tandem with shifts in the acceptability of overtly expressed prejudicial beliefs and behaviors; shifts in the general language used to describe prejudicial thoughts, feelings, and behaviors; and shifts in the aims, operational definitions, and methodologies employed in evaluating the occurrence and harmful impacts of prejudice. The sociocultural context is immediately relevant to the identification of dominant in-groups and nondominant out-groups, with the dominance of any in-group typically reflecting both the social privilege and resource advantage associated with one or more characteristics of the in-group. Although prejudicial attitudes can be held by members of dominant in-groups and members of nondominant out-groups, it is the ability to translate prejudicial attitudes into discriminatory behavior that differentiates the two groups. This chapter provides definitions of historic and modern prejudice; a broad overview of the theories that have been forwarded to explain the development and maintenance of prejudicial attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors; a brief review of prejudice as it occurs in relation to specific nondominant cultural identities; and a brief review of the changes in assessment methodologies employed by researchers to assess the occurrence of prejudice.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Prejudice is the term used most often to capture negative thoughts and feelings toward another person that occur absent of any immediate knowledge of or engagement with the other person and largely consequent to some categorization of the person as “other.” These prejudicial thoughts and feelings can then serve to justify behavior aimed at subjugating both the individual and collective will of the other. Theoretical conceptualizations of prejudice have shifted dramatically over the past century, with prejudice first conceptualized as a natural and normative – and often overtly expressed – response of members of dominant groups to the perceived inferiority of members of nondominant groups. More recently, prejudice has been conceptualized as reflecting those attitudinal and affective responses of dominant groups toward nondominant groups that are subtle, that occur as a function of unconscious processes and are consequently deniable, and that contribute to discrimination and oppression through arguments against structural change rather than arguments against the nondominant other (Garth, 1930; Jost & Hunyady, 2002; Kendi, 2016). Shifts in the conceptualization of prejudice have occurred in tandem with shifts in the acceptability of overtly expressed prejudicial beliefs and behaviors; the general language used to describe prejudicial thoughts, feelings, and behaviors; and the aims, operational definitions, and methodologies employed in evaluating the occurrence and the harmful impacts of prejudice. Theories and empirical investigations of prejudice – those originating in the context of historic prejudice and those originating in the context of modern prejudice – are to be viewed as reflecting the societal beliefs and imperatives of the time as well as researchers’ beliefs and experiences as members of dominant and nondominant groups (Condit, 2007, 2008; Duckitt, 1992; Garth, 1930; Washington, 2007). This chapter provides definitions of historic prejudice and modern prejudice; a broad overview of the theories that have been forwarded to explain the development and maintenance of prejudicial attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors; a very brief review of prejudice as it occurs in relation to specific nondominant cultural identities; and a brief review of the changes in assessment methodologies employed by researchers to assess the occurrence of prejudice.

Defining Prejudice: A Landscape of Changing Language and Persisting Effects

The word prejudice has its origins in the Latin praejudicium, which is defined as “judgment in advance” (Merriam-Webster.com, 2019). Although the denotative meaning of prejudice establishes the word as equally applicable to prejudgments that are favorable and prejudgments that are unfavorable, the word prejudice generally connotes those negative judgments made about an individual or group that are often arrived at and maintained in the absence of direct experience with the individual or group. Prejudicial attitudes, feelings, and behaviors assume one cultural identity to be normative and other identities to be nonnormative, undesirable, and/or of potential threat to those who hold the normative identity. Any demographic, geographic, physical, psychological, or social factor can be used to establish difference and dominance. In the United States, the following identities (among others) have been presumed and promoted to be normative identities: white, male, heterosexual, able-bodied, socioeconomically advantaged, and possessing relative youth. The economic and social contracts that stamped these specific identities as “normative” and as deserving of differential influence and power have conferred upon these identities unearned advantage and have enabled some members of these dominant in-groups to harbor negative attitudes and feelings and perpetrate unchecked harms against members of nondominant out-groups (Dixon, Levine, Reicher, & Durrheim, 2012).

The definition of prejudice as judging in advance of a proper evaluation of all existing data or as judging in the absence of direct experience is as appropriate now as it has ever been. It is the change in the expression of prejudice that is captured by the distinction between historic or classical prejudice and modern prejudice. Historic prejudice generally refers to prejudices that were expressed overtly and manifested routinely in the context of individual and collective striving (Allport, 1954). Historic prejudice would capture those racist views regarding the supremacy of whiteness that have been forwarded without apology throughout United States history, including the present moment. Historic prejudice also captures those sexist views regarding the supremacy of maleness that have yet to be excised from our societal unconscious – the store of conventional thought and behavior that is accessed automatically, held as truth, and enacted without careful analysis – or from the conscious practices of our public and private institutions. Modern prejudice is a term that reflects a shift from overt or explicit expressions of prejudice to far more subtle, indirect, and covert expressions of prejudice, largely in response to shifts in social norms related to the acceptability of expressed prejudice (Crandall & Eshleman, 2003; Crandall & Stangor, 2005). Modern racism permits the use of biased selection criteria to exclude black and brown students from undergraduate and graduate education to be accompanied by laments regarding the absence of a pipeline of racially diverse and qualified candidates. Modern sexism intersects with modern racism to permit unequal advancement of women and racially diverse persons to the ranks of business CEOs and senior managers (Thomas et al., 2018) and maintain a gap of 47% between the wage earned by a white male and the wage earned by an Hispanic/Latina woman who hold the same position and responsibilities (Miller & Vagins, 2018). Of course, the current emphasis on modern prejudice does not obviate the occurrence or importance of historic forms of prejudice . While it is true that crosses are being burned less frequently on the lawns of African American property owners, it is also true that uniformed officers employed for the express purpose of serving and protecting United States citizens kill unarmed African American citizens and, in most instances, do so without consequence of prosecution (Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, 2018). At the extremes, modern prejudice represents a shift from complete justification of prejudicial attitudes, feelings, and discriminatory behavior as responses to threats posed by nondominant out-groups to the wholesale disavowal of the detrimental impacts – and sometimes even the occurrence – of the ongoing discrimination and oppression members of nondominant out-groups endure (Dixon et al., 2012).

Changes in the language used to describe prejudice go well beyond the shift from historic or overt prejudice to modern or covert prejudice. The past decades have witnessed a shift in the labels applied to the processes that explain prejudice and the persons who embody prejudice. We have moved away from terms such as racism and sexism – used to describe prejudicial beliefs and behaviors toward people with nondominant racial, gender, or sexual identities – to terms such as stereotyping and unconscious or implicit bias (Banaji & Greenwald, 1995). These language changes can be viewed as an attempt to normalize what others consider a pathological orientation toward engagement with difference (Dixon et al., 2012; Kendi, 2019). Sexist persons are to be thought of as acting out of stereotyped depictions of womanhood to which they have been exposed in the larger societal context and are to be regarded as less individually culpable for the impacts resulting from the sexist behaviors they perpetrate. Antisemitic and Islamophobic persons are to be thought of as acting out of the activation of unconscious or implicit biases, applauded for holding no conscious biases, and forgiven due to the unintentional nature of any harms they cause.

The current societal and global context requires the use of precise language to describe prejudicial attitudes, feelings, and behaviors; the generation of culturally informed theories that explain the development and maintenance of prejudicial attitudes and feelings and specify those individual and situational factors that predict the enactment of prejudicial attitudes and feelings; and the conduct of quantitative and qualitative research that examines the causes of prejudice and the individual and societal harms resulting from the enactment of prejudice. The immediately following section presents an overview of theories proposed to explain the occurrence and maintenance of prejudicial attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors.

Theories of Prejudice: An Acknowledged Effort to Understand (and Unacknowledged Effort to Normalize) the Need to Classify and Dominate

Theories that propose to explain the occurrence and maintenance of prejudicial thoughts, feelings, and behaviors abound. The earliest investigations of prejudice occurred in the context of scientists addressing “the problem of racial differences in mental traits” (Garth, 1930, p. 329), with much of the “scientific” inquiry of that time seemingly motivated by the need to prove the existence of biologically determined racial differences in intellectual functioning (Garth, 1925; Woodworth, 1916). In fact, Garth (1925) suggests that much of the early twentieth century literature on racial difference reflects the subjective beliefs of the writers, noting that:

But we shall now note the attitude of these writers toward the question of equality or inequality of races. In fact, as these studies are examined the thing most predominant is a characteristic state of mind, not a new one on the part of professional and lay thinkers, and that is a belief in racial differences in mental traits. The positive belief is pretty thoroughly held by almost all of these theoretical writers. According to them it is a serious mistake to think of all human minds as the same. (p. 343)

Published challenges to the presumption of race-based differences began in earnest during the second half of the 1920s. Based on his review of race psychology articles published in the 5-year period between 1925 and 1929, Garth (1930) concluded:

What then shall we say, after surveying the literature of the last five years, is the status of the racial difference hypothesis? It would appear that it is no nearer being established than it was five years ago. In fact many psychologists seem practically ready for another, the hypothesis of racial equality. But the problem in either case is the same as it was—to obtain fair samplings of the races in question, to control the factor of nurture, and to secure a testing device and technique fair to the races compared. (p. 348)

Findings from Garth’s review can be viewed as marking a dramatic shift in scientific efforts to establish the contribution of environmental factors to racial differences previously presumed to be due to biological factors. World events during the 1930s and 1940s heralded an equally dramatically shift in the conceptualization of prejudice. Over the subsequent 70 years, early and more contemporary theorists have been challenged to explain prejudice at the level of the individual and the group and to propose strategies to reduce prejudice.

Although physical characteristics such as sex and skin color have and continue to be forwarded by some as accounting best for group differences on a host of indices, including intellectual aptitude (e.g., Herrnstein & Murray, 1994), basic genetic research has served to falsify such beliefs at the level of science (Condit, 2007, 2008; DeSalle & Ian Tattersall, 2018), if not at the level of dogma. Beliefs around the biologically-based superiority of one racial group relative to another racial group are prejudicial beliefs. Prejudicial actions taken out of those beliefs – whether they involve affording one group unmerited advantage or affording another group unmerited disadvantage – constitute discriminatory behavior. Most of the theories proposed since the middle of the twentieth century posit that prejudice is the result of individual differences in personality (Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, & Sanford, 1950) and individual and group concerns about access to resources and social identity (Allport, 1954; Altemeyer, 1988, 1998; Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994; Sherif, 1966; Tajfel & Turner, 1979, 1986). The reader is referred to Böhm, Rusch, and Baron (2018) for a comprehensive review of psychological theories of intergroup conflict.

First formulated by Adorno et al. (1950) in reaction to the atrocities that defined the Holocaust, the authoritarian personality theory contends that, in response to early socialization, individuals who possess traits consistent with authoritarianism tend to: (1) hold fast and promote adherence to social hierarchies, revering those in authority and viewing those of inferior status as subject to their control; (2) hold fast to accepted doctrine, viewing competing ideologies – and those who forward them – as threatening societal order; and (3) view maintenance of social order and the quelling of perceived threats as warranting and justifying extreme acts of oppression and violence.

In the context of the racial/ethnic prejudgments that ignited and fueled the Holocaust, one of history’s most horrific examples of racial/ethnic hatred and violence, traits of authoritarianism would lead members of the dominant group to view with mounting suspicion any person or group of persons who differed significantly from the dominant group. A difference in race/ethnicity was sufficient to prejudge Jewish persons as holding a different world view and espousing a different doctrine, as insufficiently respectful of established authority and their “place” on the hierarchy, and as threatening anarchy by virtue of their failure to live according to the established economic and social order. Such prejudgments of threat have served to justify dominant groups’ efforts to subjugate and control nondominant groups.

The authoritarian personality theory has been challenged on both theoretical and methodological grounds (Böhm et al., 2018; Duckitt, 2015; Sibley & Duckitt, 2008). The challenges to the authoritarian personality theory that we view as most relevant to the advancement of research on prejudice were those that criticized the theory as being too context specific, explaining prejudice in the context of extraordinary racial/ethnic hatred and violence, and capturing prejudice at the level of psychological pathology rather than at a “normative” level, this last challenge seeming to ignore the fact that – throughout human existence – “normative” prejudice has been associated with acts of discrimination, aggression, and extreme violence.

The 1950s heralded the formulation and dissemination of theories that characterized prejudice as a normal response to difference (Allport, 1954) and as a natural, survival-oriented approach to processing information and making decisions about the likelihood that a given individual or group will serve to strengthen one’s self and group identities or challenge those identities (Sherif, Harvey, White, Hood, & Sherif, 1961; Sherif & Sherif, 1953; Tajfel & Turner, 1979, 1986). Realistic group conflict theory (Sherif, 1966) emphasized intergroup conflict as driven by competition for resources, with intergroup conflict moderated by the degree to which the attainment of desired resources requires intergroup cooperation. Related theories include social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979, 1986), which posits that prejudice is a natural outgrowth of the process of categorizing individuals as belonging to an out-group and as threatening the integrity/sustainability of the in-group, and integrated threat theory (Stephan & Stephan, 2000), which posits that intergroup conflict can result from perceived threats to essential/real/structural resources or psychological resources.

To appreciate the true value of these well-established and often researched theories of prejudice, they must be placed in the sociopolitical context that shaped their development and the development of their authors. In the United States, the second half of the twentieth century was defined by highly organized efforts to protest the ongoing colonization of indigenous peoples; place a glaring spotlight on institutionalized racism in the form of discriminatory employment and housing practices and unequal access to education, healthcare, political participation, the rule of law, and basic consumer goods and services; and protest gender inequalities with respect to employment opportunities and compensation and argue for the basic right to physical safety and the power to make health decisions. The prejudice and discrimination that defined the lives of so many out-group members during this period of history might have served as a catalyst for the crafting theories that emphasized prejudice as occasioning the atrocities suffered by African Americans during the Jim Crow era and in response to the Black Power movement; the accusations of subversion and treason against homosexuals during the McCarthy investigations and the police harassment of members of the LGBTQ community that led to the Stonewall Riots; and the physical and psychological violence perpetrated against indigenous peoples in the context of the ongoing theft of native lands and the forced assimilation of indigenous peoples through the culture-killing practices of residential schools. Researchers active during this period of history might have investigated the direct and indirect effect of intrapersonal, interpersonal, political, and social factors on the relation of “normal cognitive-affective responses to difference” to individual-perpetrated and group-perpetrated acts of discrimination and aggression. Instead, the theories of prejudice proffered during the middle and later part of the twentieth century have been criticized as insufficiently comprehensive with respect to the factors addressed by any single theory, as disregarding the sociocultural and sociopolitical events that are likely to have influenced shifts in theory dominance, and as failing to perceive the value of combining different aspects of popular theories into one integrated framework (Böhm et al., 2018; Duckitt, 1992, 2015).

In contrast to many of the theories forwarded during the second half of the twentieth century, Henry and Tator’s (1994) theory of democratic racism presents a view of modern prejudice that recognized both the subtlety with which members of dominant in-groups express their prejudicial attitudes and feelings and the very subtle ways in which members of dominant in-groups enacted their prejudices at the level of governmental law and policy. Henry and Tator used the term “democratic racism ” to describe individuals who espouse an unwavering commitment to democratic principles and hold prejudicial attitudes toward members of nondominant racial groups. By insisting that any effort to manage racial discrimination by changing the structure of the established democracy serves to undermine that democracy, these individuals use their democratic zeal to resist efforts to end institutionalized racial discrimination. Similar efforts to reframe antidiscrimination efforts as threatening the sanctity of long-standing governmental and institutional structures are underway in the United States and in countries across the world. For example, some argue that efforts to establish wage parity and efforts to ensure a national-wide increase in the minimum wage challenge have the potential to de-stabilize the United States as a capitalist democracy. Of course, ensuring the strength of the United States as a capitalist democracy is a stance that would be championed by many. Unfortunately, support of policies that maintain the strength of our capatilist democracy often serves to passively maintain many of our nation’s most sexist, racist, and classist practices. Around the world, arguments in favor of maintaining the status quo serve to ensure that social, political, and economic influence and power are differentially available to members of dominant in-groups and will remain so.

Modern Prejudice in the Context of Single and Intersecting Cultural Identities

Modern prejudice can be expressed in relation to a myriad of cultural factors , including age, developmental and acquired disability, religion, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, indigenous heritage, language, nationality, citizenship status, gender identity and gender expression, and others (Hays, 2008) . This discussion of modern prejudice emphasizes those stereotypes held in relation to certain cultural identities and the translation of such stereotypes into acts characterized as microaggressions and acts of violence. This section also provides a breif review of the impact of modern prejudice on persons who can be considered to hold non-dominant cultural identities as a function of their racial identity, gender identity, sexual orientation, ability/disability status, and religious/spiritual affiliation.

Stereotypes are conceptualized by Greenwald and Banaji (1995) as a set of socially shared beliefs about a group based on some demographic characteristic. These “shared” and widely communicated beliefs have their most immediate and insidious negative effect through what has been termed stereo type threat. Stereotype threat captures the impact of such stereotypes on the self-concept and identity of members of targeted groups (Steele, 1997; Steele & Aronson, 1995). Stereotype threat can be viewed as active when a falsely-held stereotype serves to impact the performance of members of targeted groups. For example, when false beliefs about the inferior math abilities of females contribute a young female high school student's decision to not enroll in an advanced math course despite an academic record that predict successful performance in the course, stereotype threat is in effect. Most disturbing is the fact that the negative impacts of stereotype threat on academic choices and performance often occur outside of active awareness and these impacts are rarely part of calculations made regarding the predicted level of success to be achieved by students who hold culturally diverse identities.Microaggressions is the term coined by Sue et al. (2007) to describe the different forms of racism experienced by members of nondominant racial groups. These researchers described microaggressions as “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward people of color” (p. 271). Microaggressions are considered to include the following three forms: microassaults, microinsults, and microinvalidations. Microassaults are overt forms of racism, which include verbal and nonverbal behavior that are explicitly racist and intended to harm. Microinsults are often unintentional and unconscious statements which are demeaning, while microinvalidations are statements that negate an individual’s experience of racism. Research has established that the experience of microaggressions results in a myriad of negative consequences for the people who hold diverse cultural identities in relation to their gender (Nadal, 2011), sexual orientation (Sue & Capodilupo, 2008), disability status (Keller & Galgay, 2010), and religious affiliation (Nadal, Issa, Griffin, Hamit, & Lyons, 2010).

Race

In the United States, race is one of the socially constructing identities that has been used most effectively to ensure differential access to basic rights and resources. The majority of early research on racial prejudice examined racist beliefs held about African Americans, with much of that research highlighting the prejudical beliefs held in relation to the physical and intellectual abilities of African Americans and in relation to tendecies toward criminal engagement. More recently, research has been undertaken to document the experiences and impacts of racial prejudice and discrimination on involved Asian and Latino populations. Although the empirical literature addressing racism directed at Native Americans and Alaska Natives is small, findings indicate that the physical and psychological harms experienced by these indigenous populations are as signicant as those experienced by other targets of racial prejudice and discrimination (Paradies, 2018).

African Americans report having the experience of being exoticized due to certain physical features and sexualized due to false beliefs that have been propogated regarding their sexual anatomy and appitite (Nadal, 2011). African Americans are alternately perceived as superhuman and subhuman, being of inferior intellect and meriting none of the rights and dignities afforded to persons (Hall, Hall, & Perry, 2016; Nadal, 2011; Torres, Driscoll, & Burrow, 2010) (Hall, Hall, & Perry, 2016). African Americans also experience prejudice in the form of being perceived as intellectually inferior (Nadal, 2011; Torres, Driscoll, & Burrow, 2010) and subhuman (Hall et al., 2016). As would be predicted, widely communicated stereotypes regarding African Americans’ intellectual abilities has resulted in stereotype threat and the negative impact of stereotype threat on the performance of African Americans has been documented in the context of standardized tests of intelligence and scholastic aptitude (Nadler & Clark, 2011; Nguyen & Ryan, 2008) and academic achievement (Walton & Spencer, 2009).

As targets of stereotypes and microaggressions, African Americans experience a host of deleterious physical (Borrell et al., 2010; Brondolo et al., 2009; Lee, Kim, & Neblett Jr., 2017; Sims et al., 2016), psychological (Brondolo et al., 2009; Carter, 2007; Pietrse, Todd, Neville, & Carter, 2012; Torres et al., 2010; Utsey, Giesbrecht, Hook, & Stanard, 2008), and cognitive (Salvatore & Shelton, 2007) outcomes. Coping with the daily challenge of prejudice contributes to increased alcohol and tobacco use, improper nutrition, hypertension, and higher rates of depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress responding, and cognitive impairment among African Americans. The stereotype suggesting heightened criminality among African Americans has translated to acts of discrimination and oppression that are especially disturbing (Hall et al., 2016). A significant proportion of African Americans report the experience of being harassed by police officers without cause (Torres et al., 2010). Young African American males are imprisoned at a rate far higher than their representation in the larger U.S. population. African American children are more likely than Caucasian children to be sentenced as adults and comprise 58% of all children sent to serve sentences in adult correctional facilities (National Council on Crime and Delinquency, 2007). The most alarming finding is that African American civilians, both male and female, are more likely to be treated with excessive force and killed by police than white civilians (Edwards, Lee, & Esposito, 2019; Hall et al., 2016). These race-based differences in arrest and incarceration rates are used by members of dominant in-groups to reaffirm their belief in the criminality of nondominant racial groups. Despite the long history of racism and racial injustice in the United States, evidence that social and economic racism are key factors that drive racial differences in who is arrested, who is prosecuted, who receives what sentence, and who possesses demographic characteristics that can be deemed sufficient to justify murdered is ignored or dismissed (for recent reviews of this literature, see Alexander, 2010, Davis, 2016, and Kendi, 2016).

Asian Americans also experience considerable and varied types of prejudice. Using a focus group methodology, Sue et al. (2007) documented the experience of microaggressions as reported by Asian Americans and categorized their experiences as represented by eighth themes: alien in own land; pathologizing cultural values/communication styles; ascription of intelligence; exoticism of Asian American women; denial of racial reality; invalidation of interethnic differences; second-class citizenship; and invisibility. Asian Americans have the experience of feeling like an alien in their own country when asked, “Where were you born?” and are expected to feel complimented when told “You speak good English.” These experiences cause some Asian Americans to feel like perpetual foreigners even when having grown up in the United States (Museus & Park, 2015). Ascription of intelligence is considered a positive stereotype. Although intended as a compliment, it is form of categorization that limits the individuality of the person. Prejudice in the form of ascription of intelligence would capture the belief that all Asians are possessed of superior math abilities. The experience of positive prejudice among Asian Americans can lead to increased tension with other racial groups such as Latinos and African American (Sue et al., 2007). This stereotype can cause Asian Americans to feel trapped and feel a need to perform in a manner that conform with societal beliefs and expectations (Nadal, Wong, Griffin, Davidoff, & Sriken, 2014). Denial of racial reality is best captured by Asian Americans being described as “the new Whites” or “model minorities” (Museus & Park, 2015; Sue et al., 2007).

Some of the more widely disseminated prejudical beliefs about Latinos are similar to those held about African Americans and these prejudicial beliefs are just as likely to translate to experiences of stereotype threat and acts of discriminatory behavior that target Latinos. Using a focus group methodology similar to that employed by Sue et al. (2007), Rivera, Forquer, and Rangel (2010) documented and categorized experiences of racism reported by representatives of the Latino community. Experiences of racism were represented within seven themes: ascriptions of intelligence; second-class citizens; pathologizing communication styles or cultural values; characteristics of speech; aliens in own land; assumptions of criminality; and invalidation of the Latino/a American experience. These racial stereotypes translate to discriminatory behavior and poorer health outcomes among Latinos. Latino children are consistently underrepresented in gifted and talented programs (Ford, Scott, Moore, & Amos, 2013). Latino males are at significantly greater risk of suffering disparate treatment at the hands of U.S. law enforcement officers (Sadler, Correll, Park, & Judd, 2012), with Latino males being more likely to be killed by police officers than white males (Edwards et al., 2019). Research indicates that detrimental impacts of racism on the physical and mental health of Latinos is even greater than those experienced by African Americans (Paradies et al., 2015).

Gender

Women are negatively impacted by modern sexism in a variety of contexts , including education, career progress, and physical safety (Catalyst, 2016; Center for the American Woman and Politics, 2018; Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services, 2018; Ginder, Kelly-Reid, & Mann, 2018; Herrero, Rodríguez, & Torres, 2017; Kuchynka et al., 2018). Women are significantly less likely to obtain high leadership roles, despite often surpassing men in the number of bachelors and advanced degrees earned, with current data revealing that women represent only 5% of CEOs, 24% of United States senators, 18% of state governors, 23% of United States congressional representatives, and 6.7% of military officers at the level of brigadier general or higher (Catalyst, 2016; Center for the American Woman and Politics, 2018; Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services, 2018). Women are also underrepresented in university Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) departments and programs. Kuchynka and colleagues (2017) found that female gender and feminine attributes were less likely correlated with STEM competence and stereotypes predicted lower STEM grade point averages and lower STEM major intentions. Clearly, sexism significantly impacts women’s career trajectories and limits their educational possibilities.

Women are also disadvantaged due to the restrictive nature of traditional gender roles (Smith, Caputi, & Crittenden, 2012). In the context of heterosexual relationships, women have significantly greater responsibility for domestic duties than their partners do, despite being involved in paid outside occupations (Smith et al., 2012). This phenomenon is known in the literature as working the “second shift” (Hochschild & Machung, 1989). Women are more likely to experience depression and marital dissatisfaction when they hold an unequal share of domestic responsibilities (Coltrane, 2000; Stockard & Johnson, 1992). Sexism is also associated with higher levels of violence for women (Herrero et al., 2017). Individuals who endorse sexist beliefs are more likely to hold accepting attitudes toward interpersonal violence (IPV), and individuals who hold accepting attitudes toward IPV are more likely to engage in it.

Research has identified two types of modern sexism: hostile sexism and benevolent sexism (Glick & Fiske, 1996). Hostile sexism in the workplace is associated with experiences of depression, physical illness symptoms, absence from work, and low levels of job satisfaction for women (Fitzgerald, 1993). Benevolent sexism results in self-objectification and body shaming among women (Calogero & Jost, 2011) and can be associated with poorer cognitive performance (Dardenne, Dumont, & Bollier, 2007). Regardless of type of sexism, sexism limits women’s power in society and preserves unearned advantage due solely to maleness.

Oppression among transgender persons is part of the sexism discussion (Nadal, Whitman, Davis, Erazo, & Davidoff, 2016). Although transgender individuals are included as members of the community of persons who hold non-mainstream sexual orientations and gender identities , studies examining sexism in transgender population are relatively few in number compared to studies examining other members of the LGBTQIA (i.e., lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual) community. Transgender individuals faced with microaggressions experience anger, hopelessness, fatigue, and feelings of invalidation (Nadal et al., 2016). Some individuals do not recognize the validity of transgender individuals, and discrimination is associated with suicidality, symptoms of depression, substance abuse, and increased risk of violence and sexual assault (Schuster, Reisner, & Onorato, 2016). Transgender individuals encounter a unique form of adversity and require more empirical attention to more accurately capture their experiences with being mistreated.

Sexual Orientation

Sexual prejudice is recognized in the literature as negative attitudes and beliefs held about individuals due to their sexual orientation (Herek, 2000). More often than not studies of sexual prejudice have included some combination of individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB). It has been found that LGB individuals exposed to microaggressions experience lower self-esteem, negative feelings pertaining to their sexuality, and challenges in establishing positive feelings about their sexuality (Nadal et al., 2016). LGB individuals are also more likely to develop psychological disorders, including depression and anxiety, than heterosexual individuals (Cochran & Mays, 2009; Cochran, Mays, Alegria, Ortega, & Takeuchi, 2007; Cochran, Sullivan, & Mays, 2003; Gilman et al., 2001; Sandfort, de Graaf, Bijl, & Schnabel, 2001). In their examination of the impact of stereotypes on the health and well-being of young adults who identified as gay, lesbian, or bisexual, Woodford, Howell, Silverschanz, and Yu (2012) determined that hearing the phrase “That’s so gay” on their college campus was associated with reports of reduced appetite, increased headaches, and greater perceptions of being social ostracized among these young adults.

Gay and lesbian individuals are discriminated against in parenting and coaching roles due to their sexual identities (Massey, Merriwether, & Garcia, 2013; Sartore & Cunningham, 2009). Homosexual parents were classified as less accountable, capable, nurturing, emotionally stable, and sensitive than heterosexual parents (Massey et al., 2013). Gay and lesbian coaches are also impacted by prejudicial attitudes (Sartore & Cunningham, 2009). Parents with prejudicial attitudes are less likely to allow a homosexual coach to train their children, and athletes with prejudicial attitudes are less willing to participate in a sport that involves a homosexual coach (Sartore & Cunningham, 2009). Gay men who experience more discrimination reported higher nonprescription drug use, more doctor visits, and higher amounts of sick days used from work than bisexual men (Huebner & Davis, 2007).

Bisexual individuals comprise a unique subgroup of sexual minorities in that they are often excluded by both homosexual and heterosexual communities (Balsam & Mohr, 2007; Mulick & Wright Jr., 2002). Bisexuals experience greater negative outcomes than both heterosexuals and homosexuals, such as more negative beliefs about their sexual identity, confusion about their sexual identity, experiences of harassment and violence, unhealthy drug and alcohol consumption and weight control procedures, anxiety, depression, and suicidality (Jorm, Korten, Rodgers, Jacomb, & Christensen, 2002; Nadal et al., 2016; Robin et al., 2002; Sarno & Wright, 2013).

Religious/Spiritual Affiliation

Religious/spiritual affiliation or orientation represents another contexts in which prejudice and discrimination occur. Research examining the general relation between prejudice and religious/spiritual affiliation has produced largely inconclusive findings (Shaver, Troughton, Sibley, & Bulbulia, 2016). One consistent finding revealed by a meta-analytic review of religious racism is that religiously affiliated persons tend to hold more prejudicial attitudes and belifs about others and tend to be more judgmental of others (Hall, Matz, & Wood, 2010).

Due to the significance of national and international events that have occurred in recent times, individuals who identify as Muslim have received considerable research attention. Research suggests that Muslims have experienced less acceptance than any other religious, ethnic, or racial group with the exception of atheists (Edgell, Gerteis, & Hartmann, 2006). Muslim Americans are more likely than any ethnic group to be considered violent and untrustworthy (Sides & Gross, 2013) and there has been a 1700% increase in hate crimes against Muslims since the terrorist attacks in New York City (American Civil Liberties Union, 2002; Council on American-Islamic Relations, 2005; Ibish, 2003). Muslim Americans are one of the few groups toward which people are willing to overtly express prejudice and restrict rights and access to resources (Kteily, Bruneau, Waytz, & Cotterill, 2015; Lajevardi & Oskooii, 2018). Findings from a study examining the psychological health of Arab and Muslim Americans following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks reveal that Arab and Muslim American experience prejudice and discrimination (77%), these experiences taking the form of discrimination in the workplace and loss of employment, incidents of name-calling and communication of negative attitudes and beliefs, and physical attacks and human rights violations. More than 60% of study participants endorsed symptoms of depression in response to their experiences of religious and racial prejudice and discrimination. These studies have demonstrated the ability of dominant in-groups to dehumanize persons who hold nondominant religious identities.

Disability

Within the United States, approximately 50 million people are characterized as living with a disability (Okoro, Hollis, Cyrus, & Griffin-Blake, 2018), that is, living with a physical or mental ciscumstance that impedes their ability to perform tasks that define a particular performance domain. Despite the domain-specific nature of disabilities, individuals who manifest diverse physical and mental abilities often bear the burden of being presumed to unable to meet most of life's day-to-day challenges (McCaughey & Strohmer, 2005). In addition to battling routine presumptions around their general competence and performance abilities, individuals with atypical intellectual, physical, and psychological abilities and needs are often the target of steroetypes that cast them as asexual (DeLoach, 1994), sexually deviant (Toomey, 1993), and psychologically unstable and posing a danger to others (McCaughey & Strohmer, 2005; Werner, 2015).

As is true in relation to other cultural identites, prejudices held in relation to disability status often translate to discriminatory behaviors. Research findings indicate that children and youths with atypical abilities and needs are often isolated from their peers in the school setting and are more likely to be suspended or expelled in response to rule infractions (Leone, Mayer, Malmgren, & Meisel, 2000). Adults with diverse abilities and needs are more likely to experience discrimination at work (Harpur, 2014). and more prone to psychological distress (Dagnan & Waring, 2004). Individuals with atypical abilities and needs also experience discrimination related to basic civil rights. One in seven individuals who are of voting age can be characterized as having atypical abilities and needs (Houtenville & Ruiz, 2012). Despite this fact, 73% of all polling locations used during the 2008 elections had potential impediments for individual with a physical disability (Schur & Adya, 2012). Individuals with intellectual disabilities experience even greater challenges to their basic civil rights (Schur, Adya, & Kruse, 2013). Individuals with disabilities are often ignored by mainstream media (Morris, 1991) or represented in manners consistent with negative stereotypes (Haller, 2010). Distorted portrayals of nondominant out-groups can negatively impact the performance of out-group members, challenge their own sense of identity (Ben-Zeev, Fein, & Inzlicht, 2005), and pose a significant threat to their psychological well-being (Dagnan & Waring, 2004).

Prejudice in the Context of Intersecting Cultural Identities

Recognizing the intersection of gender, race, sexual identity, socioeconomic status, national origin, age, religion, and disability status allows for a more thorough understanding of an individual’s experience. Based on their review of the microaggressions literature, Nadal and colleagues (2015) determined that most studies address microaggressions occurring in relation to a single cultural identity rather than the multiple, intersecting cultural identities that all people hold. The intersectionality of gender and race has received some empirical attention. African American males reportedly experience more microaggressions in the form of assumptions of criminality and second-class citizenship than African American females (Bennett, McIntosh, & Henson, 2017), while Latino women experience more workplace and school microaggressions than Latino men (Nadal, Mazzula, Rivera, & Fujii-Doe, 2014).

Nadal et al. (2015) used data from six qualitative studies to examine microaggressions occurring in relation to the intersection of gender, race, ethnicity, sexual identity, and religion. Focus group responses were characterized as capturing seven microaggression themes: exoticism of women of color; gender-based stereotypes for lesbian women and gay men; approval of LGBT identity by racial, ethnic, and religious groups; assumption of inferior status; invisibility and desexualization of Asian men; assumptions of inferiority or criminality of men of color; gender-based stereotypes of Muslim men and women; and women of color as spokespersons. The microaggression themes identified in the context of this study of intersecting cultural identities are largely consistent with the microaggressions identified in the context of studies addressing a single cultural identity (e.g., Asian American). Although researchers are already engaged in the creation of assessment tools that address prejudice at the level of more than one cultural identity (Balsam, Molina, Beadnell, Simoni, & Walters, 2011; Lewis & Neville, 2015), more research is needed to properly assess the impact of prejudice on intersectional lives.

Evaluating Modern Prejudice: Documenting Both the Occurrence and the Associated Harms

Evaluation of the impact of modern prejudice on nondominant out-groups requires the use of psychometrically sound assessment tools. Instruments used in the study of modern prejudice usually query prejudicial attitudes in relation to a singular cultural identity. Many of the early measures of modern prejudice addressed prejudicial attitudes, beliefs, and feelings held in relation to a specific racial identity or gender (Glick & Fiske, 1996). For example, research evaluating prejudicial attitudes toward African Americans generally addresses beliefs pertaining to discrimination as a historic occurrence rather than an current, ongoing circumstance, feelings of antagonism toward African Americans due to their persistent claims of discriminatory and unfair treatment, and feelings of resentment toward African Americans due to their receipt of special consideration in the form of employment quotas, for example. Measures of prejudice as experienced by African Americans assess the frequency of such experiences (e.g., the Perceived Racism Scale; McNeilly et al., 1996) and/or the impact of such experiences (e.g., the Index of Race-Related Stress; Utsey & Ponterotto, 1996). Currently, considerable research effort is being devoted to the assessment of prejudice occurring in relation to other cultural identities, including gender, disability status, religion, and sexual orientation (Lajevardi & Oskooii, 2018; Legge, Flanders, & Robinson, 2018; Nadal et al., 2012; Peters, Schwenk, Ahlstrom, & McIalwain, 2017). With increasing awareness of the fact that individuals hold multiple, intersecting cultural identities, we can anticipate the development of measures that evaluate prejudice at an increasing level of complexity.

Consistent with the notion of modern prejudice as reflecting the presence of prejudicial attitudes and feelings and the desire to not appear to hold such prejudices, researchers are examining the differential impacts of feeling motivated to express prejudice versus feeling motivated to not express prejudice. In developing and establishing the soundness and utility of the Motivation to Express Prejudice Scale, Forscher, Cox, Graetz, and Devine (2015) conducted seven studies that involved more than 6,000 participants. Findings from two of the studies revealed that, relative to participants who evidence low motivation to express prejudice, participants who evidenced high motivation to express prejudice were less supportive for programs aimed at increasing contact among persons of different races, were more supportive of political candidates who opposed same-sex marriage and who framed their message in the language of either antigay values or family values, and were less supportive of political candidates who championed same-sex marriage and who framed their message in the language of equality. Plant and Devine (1998), in a three-part study involving seven samples, demonstrated that high scores on the Motivation to Respond Without Prejudice Scale were associated with high stereotype endorsement, whether participants’ reports were private or public.

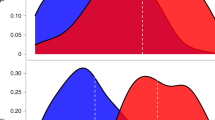

Although recent years have been marked and marred by a resurgence of some of the most overtly ableist, antisemitic, Islamophobic, homophobic, racist, sexist, transphobic, and xenophobic behavior, the past two decades have witnessed a burgeoning of research effort aimed at recognizing and minimizing the impacts of covert prejudice or implicit bias. Implicit bias refers to a cognitive process in which associations are made between concepts without requiring active, conscious awareness of the associations that have been formed (Banaji & Greenwald, 1995). In studying implicit bias, researchers are employing reaction time tasks as a method of capturing prejudice at the level of unconscious processes (Forscher & Devine, 2016). One of the most respected measures that employs this methodology is the Implicit Association Test (IAT: Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwartz, 1998). The IAT is structured as a double discrimination task in which participants respond as quickly as possible to paired stimuli that are presented as words or pictures. Bias is assumed to be present when reaction time differences are observed in pairing target categories (e.g., African American versus Caucasian) with specific attributes (e.g., honest versus dishonest). For example, an implicit bias in favor of Caucasians would be assumed if the time taken to pair the category Caucasian with the attribute honest was less than the time taken to pair the category African American with the attribute honest and if the time taken to pair the category African American with the attribute dishonest was less than the time taken to pair the category Caucasian with the attribute dishonest.

Research suggests that performance on the IAT correlates positively with performance on measures of explicit bias. Based on results from a meta-analysis of 126 studies that included the IAT and one explicit prejudice measure, Hofmann, Gawronski, Gschwendner, Le, and Schmitt (2005) concluded that the association between levels of implicit bias revealed by the IAT and levels of explicit bias revealed by self-report measures is strengthened with increasing spontaneity of self-reports and increasing correspondence between measures. Findings from a more recent meta-analysis suggest that the relation of IAT performance to performance on measures of explicit bias is less strong than previously reported and call into question the utility of the IAT in predicting discriminatory behavior (Oswald, Mitchell, Blanton, Jaccard, & Tetlock, 2013).

The conceptualization of prejudice as a consequence of overlearned, and often erroneous, categorical associations that are automatically (and unconsciously) activated has led to the development of implicit bias trainings that aim to increase attendees’ awareness of their biases, increase their knowledge of the impact of those biases on decision-making processes across a wide array of contexts, and increase the accuracy of evaluations made about members of nondominant out-groups (i.e., reduce bias-driven negative evaluations) and members of dominant in-groups (i.e., reduce bias-driven positive evaluations). Research findings indicate that interventions aimed at modifying implicit biases are effective in reducing implicit bias and increasing concern about discrimination (Devine, Forscher, Austin, & Cox, 2012) and increasing positive behavioral intentions (Lillis & Hayes, 2007).

Despite the effectiveness of interventions designed to reduce implicit bias, we forward two cautions. First, interventions undertaken with the aim of reducing implicit bias appear to assume that reductions in negative evaluations of members of nondominant out-groups will translate to reductions in discriminatory behavior. The falsity of this assumption is addressed eloquently by Dixon et al. (2012) in their response to critiques of their 2012 article “Beyond prejudice: Are negative evaluations the problem and is getting us to like one another more the solution?” as a rejection of the potential value of prejudice reduction:

…First, we should not presume that the absence of negative intergroup feelings and conflict necessarily indicates the absence of discrimination and inequality. Second, we should not presume that their presence is necessarily an impediment to the reduction of discrimination and inequality. Third, by implication, we should not presume that nurturing warm feelings and harmonious relations necessarily creates a better society. Better for whom, in what ways, and at what costs? These are questions that have been marginalised in much of the prejudice literature, which has treated the reduction of negative evaluations as an unquestioned end in itself, quietly eclipsing more fundamental debates about how to implement sociopolitical change most effectively. (p. 452)

In their recent meta-analysis, Kurdi and colleagues (2019) examined the expanding research literature addressing the relation of the IAT to intergroup behavior. Based on their evaluation of more than 2200 implicit–criterion correlations, these researchers determined that measures of implicit cognitions predicted all types of behavior sampled across the 217 reports, with effect sizes ranging from small to moderate. Kurdi and colleagues acknowledge that the level of heterogeneity observed among the social groups, types of IATs, samples, and criterion variable employed across the research reports limits the strength of the reported findings. Of the 217 reports that involved more than 36,000 participants, only 13 studies that involved a combined sample of 54 participants were identified by the authors as permitting a reliable test of the relation of the IAT to behavior. When placed in the larger context of social action aimed at reducing discrimination, these findings can be interpreted as strengthening calls for caution regarding the usefulness of the IAT and similar measures of implicit cognition in predicting discriminatory behavior.

Second, our experiences with implicit bias trainings have generated concern about the emphasis placed on the universality of implicit biases. Trainers emphasize the universality of implicit biases but fail to acknowledge that members of dominant in-groups are far less likely to suffer harms as a consequence of prejudice and are uniquely empowered, by virtue of centuries of socially legitimized and institutionally sanctioned oppression of out-groups, to enact harms as a function of their prejudice. For a detailed discussion of a promising, new approach to implicit bias reduction that emphasizes high consistency between expressed values and actions taken in relation to those values and that is undergoing empirical evaluation, we direct the reader to chapter “Intersecting and Multiple Identities in Behavioral Health” of this book.

It can be concluded that although the number of measures of historic or explicit prejudice and modern or implicit prejudice is increasing and although different forms of prejudice are being tapped by these measures, much research is needed to evaluate the co-occurrence of explicit and implicit prejudice in relation to a single form of prejudice; to establish the co-occurrence of different forms of prejudice; to establish the degree to which explicit and implicit prejudice predict discriminatory behavior; and to identify the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and socioenvironmental factors that mediate the relation of explicit and implicit prejudice to discrimination.

Conclusion

Modern theories of prejudice can be viewed as promoting prejudice as a normative experience that can be assumed to contribute only to limited harms. As is true for all theories, modern theories of prejudice arise out of a sociopolitical agenda in which the cultural ideologies of dominant in-groups are legitimized and maintained, the fragility of dominant in-groups is prioritized, and in which members of dominant in-groups are held harmless around all the harms they perpetrate and all the harms they ignore in order to maintain dominance. Once again we find ourselves in a moment of placing more research emphasis on understanding the prejudicial attitudes and feelings of members of dominant in-groups, subtly endorsing the idea that the solution to institutionalized oppression of out-groups lies in increasing knowledge and insight regarding the cultural biases (presumably unrecognized but more likely actively unacknowledged) that advantage in-group members and disadvantage out-group members. The amelioration of aggression and violence against members of out-groups and the elimination of discriminatory practices that result in reduced access, participation, influence, and reward for out-group members require that prejudice and discrimination be addressed at the level of policy creation, policy implementation, and policy reinforcement. In addition to ensuring equality of access, opportunity, participation, influence, and reward, these policies should ensure that, when intergroup engagement occurs, in-group and out-group members are positioned to be maximally effective in achieving separate and shared objectives.

References

Abu-Ras, W., & Abu-Bader, S. H. (2009). Risk factors for depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): The case of Arab and Muslim Americans post-9/11. Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies, 7(4), 393–418.

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D., & Sanford, R. N. (1950). The authoritarian personality (p. 415). New York, NY: Harper & Brothers.

Alexander, M. (2010). The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York, NY: The New Press.

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Altemeyer, B. (1988). Enemies of freedom: Understanding right-wing authoritarianism. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Altemeyer, B. (1998). The other “authoritarian personality”. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 30, 47–92.

American Civil Liberties Union. (2002). International civil liberties report. http://www.aclu.org/FilesPDFs/iclr2002.pdf

Balsam, K. F., & Mohr, J. J. (2007). Adaptation to sexual orientation stigma: A comparison of bisexual and lesbian/gay adults. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(3), 306–316.

Balsam, K. F., Molina, Y., Beadnell, B., Simoni, J., & Walters, K. (2011). Measuring multiple minority stress: The LGBT people of color microaggressions scale. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17(2), 163–174.

Banaji, M. R., & Greenwald, A. G. (1995). Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological Review, 102(1), 4–27.

Bennett, L. M., McIntosh, E., & Henson, F. O. (2017). African American college students and racial microaggressions: Assumptions of criminality. Journal of Psychology, 5(2), 14–20.

Ben-Zeev, T., Fein, S., & Inzlicht, M. (2005). Arousal and stereotype threat. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41(2), 174–181.

Böhm, R., Rusch, H., & Baron, J. (2018). The psychology of intergroup conflict: A review of theories and measures. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2018.01.020

Borrell, L. N., Roux, A. V. D., Jacobs, D. R., Jr., Shea, S., Jackson, S. A., Shrager, S., & Blumenthal, R. S. (2010). Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination, smoking and alcohol consumption in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Preventive Medicine, 51(3–4), 307–312.

Brondolo, E., Brady Ver Halen, N., Pencille, M., Beatty, D., Contrada, R. J., et al. (2009). Coping with racism: A selective review of the literature and a theoretical and methodological critique. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32(1), 64–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-008-9193-0

Calogero, R. M., & Jost, J. T. (2011). Self-subjugation among women: Exposure to sexist ideology, self-objectification, and the protective function of the need to avoid closure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(2), 211–228.

Carter, R. T. (2007). Racism and psychological and emotional injury: Recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(1), 13–105.

Catalyst. (2016). Quick Take: Women of color in the United States. New York, NY: Author.

Center for the American Woman and Politics. (2018). Fact sheet: Women in elective office 2018. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University.

Cochran, S. D., & Mays, V. M. (2009). Burden of psychiatric morbidity among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals in the California Quality of Life Survey. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(3), 647–658.

Cochran, S. D., Mays, V. M., Alegria, M., Ortega, A. N., & Takeuchi, D. (2007). Mental health and substance use disorders among Latino and Asian American lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(5), 785–794.

Cochran, S. D., Sullivan, J. G., & Mays, V. M. (2003). Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress, and mental health services use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(1), 53–61.

Coltrane, S. (2000). Research on household labor: Modeling and measuring the social embeddedness of routine family work. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(4), 1208–1233.

Condit, C. M. (2007). How culture and science make race “genetic”: Motives and strategies for discrete categorization of the continuous and heterogeneous. Literature and Medicine, 26(1), 240–268. Project MUSE. https://doi.org/10.1353/lm.2008.0000

Condit, C. M. (2008). Race and genetics from a modal materialist perspective. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 94(4), 383–406.

Council on American-Islamic Relations. (2005). The status of Muslim Civil Rights in the United States: Unequal protection. Washington, DC: Author.

Crandall, C. S., & Eshleman, A. (2003). A justification-suppression model of the expression and experience of prejudice. Psychological Bulletin, 129(3), 414.

Crandall, C. S., & Stangor, C. (2005). Conformity and prejudice. In J. F. Dovidio, P. Glick, & L. A. Rudman (Eds.), On the nature of prejudice: Fifty years after Allport. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Dagnan, D., & Waring, M. (2004). Linking stigma to psychological distress: Testing a social–cognitive model of the experience of people with intellectual disabilities. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy: An International Journal of Theory and Practice, 11(4), 247–254.

Dardenne, B., Dumont, M., & Bollier, T. (2007). Insidious dangers of benevolent sexism: Consequences for women’s performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(5), 764–779.

Davis, A. Y. (2016). Freedom is a constant struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the foundations of a movement. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books.

Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services. (2018). Defense Advisory Committee on Woman in the Service 2018 Annual Report. (Report No. 8-1A20B83). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Defense.

DeLoach, C. P. (1994). Attitudes toward disability: Impact on sexual development and forging of intimate relationships. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 25(1), 18–25.

DeSalle, R., & Ian Tattersall, I. (2018). Troublesome science: The misuse of genetics and genomics in understanding race. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Devine, P. G., Forscher, P. S., Austin, A. J., & Cox, W. T. L. (2012). Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(6), 1267–1278.

Dixon, J., Levine, M., Reicher, S., & Durrheim, K. (2012). Beyond prejudice: Are negative evaluations the problem and is getting us to like one another more the solution? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 35, 411–466. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X11002214

Duckitt, J. H. (1992). Psychology and prejudice: A historical analysis and integrative framework. American Psychologist, 47(10), 1182.

Duckitt, J. (2015). Authoritarian personality. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences 2(2), 255–261. Oxford, EN: Elsevier.

Edgell, P., Gerteis, J., & Hartmann, D. (2006). Atheists as “other”: Moral boundaries and cultural membership in American society. American Sociological Review, 71(2), 211–234.

Edwards, F., Lee, H., & Esposito, M. (2019). Risk of being killed by police use of force in the United States by age, race–ethnicity, and sex. PNAS, 116(34), 16793–16798

Fitzgerald, L. F. (1993). Sexual harassment: Violence against women in the workplace. American Psychologist, 48(10), 1070–1076.

Ford, D. Y., Scott, M. T., Moore, J. L., & Amos, S. O. (2013). Gifted education and culturally different students: Examining prejudice and discrimination via microaggressions. Gifted Child Today, 36(3), 205–208.

Forscher, P. S., Cox, W. T. L., Graetz, N., & Devine, P. G. (2015). The motivation to express prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(5), 791–812.

Forscher, P. S., & Devine, P. G. (2016). The role of intentions in conceptions of prejudice: An historical perspective. In T. D. Nelson (Ed.), Handbook of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination (2nd ed., pp. 241–254). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Garth, T. R. (1925). A review of racial psychology. Psychological Bulletin, 22(6), 343–364.

Garth, T. R. (1930). A review of race psychology. Psychological Bulletin, 27(5), 329–356.

Gilman, S. E., Cochran, S. D., Mays, V. M., Hughes, M., Ostrow, D., & Kessler, R. C. (2001). Risk of psychiatric disorders among individuals reporting same-sex sexual partners in the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Public Health, 91(6), 933–939.

Ginder, S. A., Kelly-Reid, J. E., & Mann, F. B. (2018). Postsecondary Institutions and Cost of Attendance in 2017–2018; Degrees and Other Awards Conferred, 2016–2017; and 12-Month Enrollment, 2016–2017. (Report No. NCES 2018060REV). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(3), 491–512.

Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (1995). Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological Review, 102(1), 4–27.

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464–1480.

Hall, A. V., Hall, E. V., & Perry, J. L. (2016). Black and blue: Exploring racial bias and law enforcement in the killings of unarmed black male civilians. American Psychologist, 71(3), 175–186.

Hall, D. L., Matz, D. C., & Wood, W. (2010). Why don’t we practice what we preach? A meta-analytic review of religious racism. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(1), 126–139.

Haller, B. A. (2010). Representing disability in an ableist world: Essays on mass media. Louisville, KY: The Advocado Press.

Hays, P. A. (2008). Addressing cultural complexities in practice: A framework for clinicians and counselors (2nd ed.). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Harpur, P. D. (2014). Combating prejudice in the workplace with contact theory: The lived experiences of professionals with disabilities. Disability Studies Quarterly, 34(1), 17.

Henry, F., & Tator, C. (1994). The ideology of racism: “Democratic racism.” Canadian Ethnic Studies, 26(2), 1–14.

Herek, G. M. (2000). The psychology of sexual prejudice. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9(1), 19–22.

Herrero, J., Rodríguez, F. J., & Torres, A. (2017). Acceptability of partner violence in 51 societies: The role of sexism and attitudes toward violence in social relationships. Violence Against Women, 23(3), 351–367.

Herrnstein, R. J., & Murray, C. (1994). The bell curve: Intelligence and class structure in American life. New York, NY: Free Press.

Hochschild, A., & Machung, A. (1989). The second shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. New York, NY: Viking.

Hofmann, W., Gawronski, B., Gschwendner, T., Le, H., & Schmitt, M. (2005). A meta-analysis on the correlation between the implicit association test and explicit self-report measures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(10), 1369–1385.

Houtenville, A. J., & Ruiz, T. (2012). 2012 annual disability statistics compendium. Durham, NH: University of New Hampshire Institute on Disability.

Huebner, D. M., & Davis, M. C. (2007). Perceived antigay discrimination and physical health outcomes. Health Psychology, 26(5), 627–634.

Ibish, H., & ADC Research Institute., & American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee. (2003). Report on hate crimes and discrimination against Arab Americans: The post September 11 backlash, September 11, 2001 – October 11, 2002. Washington, DC: American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee.

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. (2018). African Americans, police use of force, and human rights in the United States. Washington, D.C.: Organization of American States.

Jorm, A. F., Korten, A. E., Rodgers, B., Jacomb, P. A., & Christensen, H. (2002). Sexual orientation and mental health: Results from a community survey of young and middle–aged adults. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 180(5), 423–427.

Jost, J. T., & Hunyady, O. (2002). Antecedents and consequences of system-justifying ideologies. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(5), 260–265.

Keller, R. M., & Galgay, C. E. (2010). Microaggressive experiences of people with disabilities. In D. W. Sue (Ed.), Microaggressions and marginality: Manifestation, dynamics, and impact (pp. 241–268). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Kendi, I. X. (2016). Stamped from the beginning: The definitive history of racist ideas in America. New York, NY: Nation Books.

Kendi, I. X. (2019). How to be an antiracist. New York, NY: One World.

Kteily, N., Bruneau, E., Waytz, A., & Cotterill, S. (2015). The ascent of man: Theoretical and empirical evidence for blatant dehumanization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(5), 901–931.

Kurdi, B., Seitchik, A. E., Axt, J. R., Carroll, T. J., Karapetyan, A., Kaushik, N., ... Banaji, M. R. (2019). Relationship between the Implicit Association Test and intergroup behavior: A meta-analysis. American Psychologist, 74(5), 569–586.

Kuchynka, S.L., Salomon, K., Bosson, J.K., El-Hout, M., Kiebel, E., Cooperman, C., & Toomey, R. (2018). Hostile and benevolent sexism and college women’s STEM outcomes. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 42(1), 72–87.

Lajevardi, N., & Oskooii, K. A. (2018). Old-fashioned racism, contemporary islamophobia, and the isolation of Muslim Americans in the age of Trump. Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Politics, 3(1), 112–152.

Lee, D. B., Kim, E. S., & Neblett, E. W., Jr. (2017). The link between discrimination and telomere length in African American adults. Health Psychology, 36(5), 458–467.

Legge, M. M., Flanders, C. E., & Robinson, M. (2018). Young bisexual people’s experiences of microaggression: Implications for social work. Social Work in Mental Health, 16(2), 125–144.

Leone, P. E., Mayer, M. J., Malmgren, K., & Meisel, S. M. (2000). School violence and disruption: Rhetoric, reality, and reasonable balance. Focus on Exceptional Children, 33(1), 1–20.

Lewis, J. A., & Neville, H. A. (2015). Construction and initial validation of the Gendered Racial Microaggressions Scale for Black women. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(2), 289–302.

Lillis, J., & Hayes, S. C. (2007). Applying acceptance, mindfulness, and values to the reduction of prejudice. A pilot study. Behavior Modification, 31(4), 389–411.

Massey, S. G., Merriwether, A. M., & Garcia, J. R. (2013). Modern prejudice and same-sex parenting: Shifting judgments in positive and negative parenting situations. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 9(2), 129–151.

McCaughey, T. J., & Strohmer, D. C. (2005). Prototypes as an indirect measure of attitudes toward disability groups. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 48(2), 89–99.

McNeilly, M. D., Anderson, N. B., Armstead, C. A., Clark, R., Corbett, M., Robinson, E. L., … Lepisto, E. M. (1996). The perceived racism scale: A multidimensional assessment of the experience of white racism among African Americans. Ethnicity and Disease, 6, 154–166.

Merriam-Webster. (2019) Miraim-Webster.com dictoionary. Retreived July 24, 2018 from http://www.merriam-webster.com/

Miller, K., & Vagins, D. J. (2018). The simple truth about the gender pay gap: Fall 2018 edition. Washington, DC: AAUW.

Morris, J. (1991). Pride against prejudice: Transforming attitudes to disability. London, UK: The Women’s Press.

Mulick, P. S., & Wright, L. W., Jr. (2002). Examining the existence of biphobia in the heterosexual and homosexual populations. Journal of Bisexuality, 2(4), 45–64.

Museus, S. D., & Park, J. J. (2015). The continuing significance of racism in the lives of Asian American college students. Journal of College Student Development, 56(6), 551–569.

Nadal, K. L. (2011). The racial and ethnic microaggressions scale (REMS): Construction, reliability, and validity. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(4), 470–480.

Nadal, K. L., Davidoff, K. C., Davis, L. S., Wong, Y., Marshall, D., & McKenzie, V. (2015). A qualitative approach to intersectional microaggressions: Understanding influences of race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and religion. Qualitative Psychology, 2(2), 147–163.

Nadal, K. L., Griffin, K. E., Hamit, S., Leon, J., Tobio, M., & Rivera, D. P. (2012). Subtle and overt forms of Islamophobia: Microaggressions toward Muslim Americans. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 6(2), 15–37.

Nadal, K. L., Issa, M., Griffin, K. E., Hamit, S., & Lyons, O. B. (2010). Religious microaggressions in the United States: Mental health implications for religious minority groups. In D. W. Sue (Ed.), Microaggressions and marginality: Manifestation, dynamics, and impact (pp. 287–310). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Nadal, K. L., Mazzula, S. L., Rivera, D. P., & Fujii-Doe, W. (2014). Microaggressions and Latina/o Americans: An analysis of nativity, gender, and ethnicity. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 2(2), 67–78.

Nadal, K. L., Whitman, C. N., Davis, L. S., Erazo, T., & Davidoff, K. C. (2016). Microaggressions toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and genderqueer people: A review of the literature. The Journal of Sex Research, 53(4–5), 488–508.

Nadal, K. L., Wong, Y., Griffin, K. E., Davidoff, K., & Sriken, J. (2014). The adverse impact of racial microaggressions on college students’ self-esteem. Journal of College Student Development, 55(5), 461–474.

Nadler, J. T., & Clark, M. H. (2011). Stereotype threat: A meta-analysis comparing African Americans to Hispanic Americans. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(4), 872–890.

National Council on Crime and Delinquency. (2007). And justice for some: Differential treatment of youth of color in the justice system. Oakland, CA: Author. Retrieved from http://www.nccdglobal.org/sites/default/files/publication_pdf/justicefor-some.pdf

Nguyen, H. H. D., & Ryan, A. M. (2008). Does stereotype threat affect test performance of minorities and women? A meta-analysis of experimental evidence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1314–1334.

Okoro, C. A., Hollis, N. D., Cyrus, A. C., & Griffin-Blake, S. (2018). Prevalence of disabilities and health care access by disability status and type among adults — United States, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67, 882–887. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6732a3externalicon

Oswald, F. L., Mitchell, G., Blanton, H., Jaccard, J., & Tetlock, P. E. (2013). Predicting ethnic and racial discrimination: A meta-analysis of IAT criterion studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(2), 171–192.

Paradies, Y., Ben, J., Denson, N., Elias, A., Priest, N., & Pieterse, A. (2015). Racism as a determinant of health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 10(9), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138511

Peters, H. J., Schwenk, H. N., Ahlstrom, Z. R., & McIalwain, L. N. (2017). Microaggressions: The experience of individuals with mental illness. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 30(1), 86–112.

Pietrse, A. L., Todd, N. R., Neville, H. A., & Carter, R. T. (2012). Perceived racism and mental health among Black American adults: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59(1), 1–9.

Plant, E. A., & Devine, P. G. (1998). Internal and external motivation to respond without prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(3), 811–832.

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Malle, F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(4), 741–763.

Paradies, Y. (2018). Racism and indigenous health. Retrieved July 2019 from https://oxfordre.com/publichealth/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.001.0001/acrefore-9780190632366-e-86