Abstract

By September 2018, Lebanon hosted an estimated 1.5 million displaced Syrians. This chapter analyses healthcare financing and service provision for them, with a focus on women, children and adolescents. We reviewed the literature on health financing and provision of health services to Syrian refugees in Lebanon and conducted an original analysis of aid to Lebanon from 2002 to 2016. The Syrian refugee population in Lebanon has placed a critical strain on the country’s economy and public services, including the health system. Aid to the humanitarian and health sectors comprised 28% ($3.2 billion) of aid to Lebanon between 2002 and 2016. Displaced Syrians in Lebanon accessing health services faced high out-of-pocket expenditures within a system dominated by private sector provision. Cash-based interventions were increasingly used to deliver aid to displaced Syrians, with subsidised private sector and free public sector primary health services. This left a significant gap in the provision of secondary and tertiary care, adding to the financial burden on refugees. Given these funding cuts, the financing and delivery of essential services to refugees in Lebanon remains precarious. This adds to existing pressures on Lebanon’s health system and challenges faced by vulnerable populations in accessing essential services.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Lebanon

- Syria

- Refugees

- Health financing

- Health system

- Health services

- Reproductive health

- Maternal health

- Newborn health

- Child health

Introduction

The Syrian crisis, which started in 2011, has caused Syrians to flee violence and persecution both internally within its borders and externally as refugees and asylum seekers seek refuge in other countries. As of August 2018, the United Nations estimated that six million refugees had fled Syria , with the majority hosted by the neighbouring countries of Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey (UNHCR 2018b).

By September 2018, Lebanon alone hosted an estimated 1.5 million displaced Syrians (UNHCR 2018b). As a result, Lebanon is the country with the highest per capita density of refugees in the world, with one in four people a refugee or displaced person. Refugees in Lebanon include Syrian refugees (UNHCR 2017a; Government of Lebanon and UNHCR 2018), Palestinian refugees recently arrived from Syria, Palestinian refugees already residing in Lebanon as well as Iraqi and other refugees (UNHCR 2018b). This substantial population shift has placed tremendous strain on the country’s economy, infrastructure and public services. The World Bank estimates that by the end of 2015, the Syrian crisis had cost the Lebanese economy $18.15 billion due to the economic slowdown, loss in fiscal revenues and additional pressure on public services (World Bank 2017). As the Syrian crisis persists, signs of heightened tensions and host-community fatigue have emerged (Government of Lebanon and UNHCR 2017).

Lebanon’s non-encampment policy means that Syrian refugees are widely dispersed throughout the country’s urban and rural areas, with the highest concentration in the Beka’a Valley bordering Syria . A 2017 interagency vulnerability assessment of Syrian refugees reported that 73% of Syrians lived in residential buildings or apartments, 17% in improvised shelters such as informal tented settlements and 9% in unofficial urban housing including garages, workshops and farmhouses (UNHCR 2017c). Almost three-quarters of Syrians in Lebanon live below the poverty line proposed for Lebanon by the World Bank in 2013 ($3.84/person/day), without legal residence, and with an average household debt of $798 (Government of Lebanon and UNHCR 2018). Of the 1.5 million refugees, less than two-thirds (n = 952,962) were officially registered with the UNHCR in September 2018, and the majority do not have a legal right to work (UNHCR 2018b). Many Syrians in Lebanon are not registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), in part because the Lebanese government asked UNHCR in 2015 to stop registering Syrians unless they were newborns of Syrian parents previously registered with UNHCR in Lebanon (Janmyr 2018). The lack of legal status of Syrians in Lebanon contributes to widespread poverty, lack of access to essential services, a risk of statelessness for the refugees’ newborn children and barriers which contribute to keeping many Syrian children out of school. Three quarters of those displaced by the Syrian conflict are women and children (UNFPA 2018), while the majority are also under 19 years. In 2018, 57% of displaced Syrians registered with UNHCR as refugees were children (0–18 years), 23% were adolescents (10–19 years) and 17% were youth (20–24 years) (Ministry of Social Affairs Lebanon and UNHCR 2018).

Displaced Syrians in Lebanon are provided access to subsidised care within Lebanon’s largely privatised health system, under both UNHCR and the Lebanese government’s mandates, irrespective of whether they are formally registered with UNHCR (DeJong 2017). However, Syrian refugees report that access to medical specialists is challenging, with 76% stating that services are unaffordable and 70% that they face barriers in accessing medication (John Hopkins University (JHU), M. D. M., International Medical Corps, Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection, American University of Beirut and UNHCR 2015). The latter finding is particularly concerning given the predominance of women and children within the Syrian refugee population in Lebanon, as women and children disproportionately account for the morbidity burden in conflict-affected populations (Sami et al. 2014; DeJong et al. 2017). Inadequate or interrupted access to reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health (RMNCH) services can increase the number of people affected by crises, generating a high risk of unintended or unwanted pregnancies, complications related to unsafe abortions, sexual and gender-based violence and an increased incidence of sexually transmitted infections (United Nations 2014; Glasier et al. 2006). These consequences, in turn, limit women’s empowerment and their participation in the recovery process, resulting in violations of their human rights, and a reduction in the resources available to alleviate suffering (Singh et al. 2018).

Lebanon has undergone extreme changes in its population structure, its economy and its societal fabric as a result of the unfolding Syrian crisis over the last 7 years. A humanitarian crisis on the scale of the Syrian war has profound effects on the health of those affected by the conflict, as well as on the health system of the countries in which they seek refuge.

This chapter aims to provide a detailed analysis of healthcare financing arrangements and service provision for Syrian refugees in Lebanon, with a focus on women, children and adolescents. Specific objectives are to (1) provide a situational analysis of the Syrian crisis and its impact on the Lebanese health system; (2) analyse health and humanitarian aid to Lebanon from 2002 to 2016; and (3) describe the health sector response to Syrian refugees in Lebanon, including how aid and healthcare is financed, in particular for Syrian refugee women, children and adolescents.

Box 4.1 Methodology

We reviewed existing literature and data on health financing, systems and provision of health services to Syrian refugees in Lebanon and analysed aid to Lebanon.

Data and Literature Search

Eligibility criteria: We included literature and datasets related to health financing in Lebanon, as well as financing arrangements and health services (including RMNCH) for Syrian refugees. We included all primary quantitative and qualitative research studies from peer-reviewed journals as well as grey literature in the public as well as private domains, as well as any reports and datasets with information on health financing and health service provision to Syrian refugees in Lebanon.

Search strategy: We searched for relevant data and published and grey literature in English and Arabic in both public (e.g. international databases, open access governmental and non-governmental websites) and domestic (e.g. Ministry of Public Health, Ministry of Finance) domains from 2011 to 2018. We searched on terms related to the following categories in combination: health financing OR access OR preferences AND general health services OR RMNCAH services AND Syrian refugees and Lebanon. The following databases were searched for published literature: EMBASE, EconLit, MEDLINE and PsychINFO and BASE for grey literature in addition to the online resources – UNICEF, UNHCR, WHO and Lebanon governmental websites. We also screened reference lists for additional relevant literature. Individuals working in governmental (e.g. national statistics office), non-governmental, academic and United Nations (e.g. UNICEF) institutions were asked for data not available online and for additional relevant literature.

Data extraction: We recorded descriptive information on data in an Excel spreadsheet, to provide an overview of what the data contains, who it is owned by, whether the questionnaire is available to the study team, whether it is publicly available and if it is not, then who the point person is. For included literature, we also recorded descriptive information in an Excel spreadsheet, to provide an overview of the author, year, title, type of literature, brief summary and relevant data for the chapter.

Analysing Humanitarian and Health Aid to Lebanon

We analysed aid to Lebanon from 2002 to 2016 using the Creditor Reporting System (CRS), a database compiled by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, to which donor countries and multilateral institutions report annually (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development 2018). We included official development assistance (ODA) and private grants from institutions and calculated annual disbursements to Lebanon in total, for the humanitarian and health sectors, and by purpose and channel within the humanitarian and health sectors. We also analysed aid to Lebanon for the humanitarian sector by donor and examined the largest humanitarian disbursements in greater depth. To determine the key humanitarian and health organisations operating in Lebanon with international funding, we analysed both humanitarian and health aid by channel, i.e. disbursements from multilateral organisations’ core budgets (where the multilateral agency was effectively the donor agency) and disbursements channelled through multilaterals by bilateral donors to implement specific activities (where the multilateral was the implementing agency). We made comparisons between humanitarian and health aid received by Lebanon and its neighbours Turkey and Jordan . We downloaded disbursement data from the CRS in July 2018 and reported them in constant 2016 US dollars. Data on refugee populations was obtained from the World Bank, downloaded in September 2018.

Overview of the Lebanese Health System

The health system in Lebanon is a public-private partnership with a number of sources of funding and delivery channels. Despite the fact that the country fosters a very high number of health insurance operators, the majority of the population cannot afford to pay for full coverage (Salti et al. 2010). In principle, the Ministry of Public Health is the funder of last resort, i.e. it is committed to pay if people do not have health insurance. Public healthcare provision is therefore required to cater for expensive long-term treatments. As such, the National Social Security Fund (NSSF), Lebanon’s national social insurance system which provides employees with health insurance cover and retirement pensions, has been recording a deficit for several years. Almost 50% of Lebanon’s population is financially covered by the NSSF or by other governmental (i.e. civil servants cooperative and military) schemes or private insurance bodies (Salti et al. 2010). These schemes provide financial coverage with variable patient co-payments, and non-adherents are entitled to the coverage of the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) for secondary and tertiary care at both public and private institutions.

MoPH provides in-kind support to a national network of primary healthcare (PHC) centres (PHCCs) across Lebanon including non-governmental and faith-based organisations (Government of Lebanon and UN 2018). These centres provide consultations with medical specialists at reduced cost, as well as medicines for chronic illness and vaccines funded by the MoPH (Ammar et al. 2016). It is estimated that 68% of the primary healthcare centres in the national network are owned by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) while 80% of hospitals belong to the private sector (Government of Lebanon and UNHCR 2018). The strong presence of the private sector in service delivery has led to an oversupply of hospital beds and technology, and while there is an oversupply of physicians, there is a shortage of nurses (A. H. C. G. Report 2016; Kassak et al. 2006). Moreover, in 2006 the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that only 8% of the population benefitted from government primary care, revealing a failing primary healthcare system (WHO 2006).

Although recent data on domestic financing for healthcare in Lebanon are unavailable, data from 2006 show that Lebanon spends almost 11.5% of gross domestic product (GDP) on health compared to an average of 5% in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, of which 75% is out-of-pocket expenditure not including insurance cover (Akala and El-Saharty 2006). Three quarters (75%) of public health spending in Lebanon funds hospital-based curative care (Akala and El-Saharty 2006). Moreover, the public sector is the major financing agent for services rendered in the private sector. According to the Ministry of Finance 2006 budget proposal, private sector hospitalisation accounts for 48% of total public health expenditure, which constitutes a significant drain on public sector finance (Salti et al. 2010). In addition, health services in Lebanon are some of the most expensive in the MENA region (Salti et al. 2010; WHO 2006).

Humanitarian and Health Aid to Lebanon

Humanitarian aid comprises a large proportion of total aid to Lebanon. On average, between 2002 and 2016, 25% of all aid to Lebanon flowed to the humanitarian sector, 3% flowed to the health sector and the remaining 72% flowed to other sectors, including education, water, transport, energy, agriculture, construction and general budget support (Fig. 4.3a). Health aid to Lebanon increased from $11 million in 2002 to $44 million in 2016, with funding peaking in 2014 at just over $47 million (Fig. 4.3c). While health aid to Lebanon increased between 2002 and 2016, overall, the proportion of aid for health remained small compared to humanitarian aid and total aid.

In contrast, humanitarian aid averaged $186 million per year, the majority of which supported “material relief assistance and services”, which can include health projects as well as provision of shelter, water, sanitation and other non-food relief items (Fig. 4.3b). Humanitarian aid fluctuated considerably over the 15-year period, with three clear peaks coinciding with the first wave of Iraqi refugees entering Lebanon in 2006, the year after the start of the Syrian war, 2012, and then in 2015 with the intensification of the Syrian war coupled with efforts by European donors to keep Syrian refugees in neighbouring territories of Jordan and Lebanon (Fig. 4.3a). The data presented reflect two distinct but interrelated refugee situations in Lebanon which are important to distinguish – that of the long-term Palestinian refugees spanning the period 2002–2010 and then from 2011/2012 the arrival of Syrian refugees in Lebanon, in addition to Palestinian refugees.

The peaks in humanitarian aid identified in 2012 and 2015, reflecting the Syrian crisis (and to a lesser degree, in 2006 in response to Palestinian refugees in Lebanon), were largely driven by funding from the USA (Fig. 4.3d). US ODA comprised 81% of all humanitarian aid to Lebanon in 2012 (a total of $252 million) and 32% ($191 million) in 2015. European Union (EU) institutions were the second-largest humanitarian donors to Lebanon over the period, contributing $562 million of ODA to the humanitarian sector between 2002 and 2016.

Having disbursed very little humanitarian ODA to Lebanon from 2002 to 2014, in 2015 the UK disbursed $104 million and in 2016 $89 million in humanitarian ODA, making it the second and third largest donor in those respective years. Germany had also contributed relatively little in humanitarian ODA to Lebanon before 2014, when it disbursed $70 million, making it the second largest donor that year after the EU institutions. Germany disbursed $25 million in humanitarian ODA in 2015, followed by $100 million in 2016, making it the largest donor to the humanitarian sector in 2016.

The three implementing agencies in Lebanon with the most aid channelled through them were the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA ) (which only provides services to Palestine refugees), UNHCR and United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) (Fig. 4.2). However, aid channelled through UNRWA in Lebanon has decreased since 2018 when the USA, the largest single donor to UNRWA, stopped funding the agency.

Although proportionally UNRWA, UNHCR and UNICEF are more dominant within health than the humanitarian sector as classified in the OECD database, the humanitarian sector received a larger proportion of the total available funding between 2002 and 2016 compared to the health sector. Over this period, more than $600 million out of a total $2.8 billion of humanitarian aid was channelled through UNRWA , compared to $230 million out of a total of $390 million of health aid (Fig. 4.1). Within the health sector, these three multilaterals were responsible for allocating the largest amount of funds in 2011 ($29 million) and 2014 ($35 million) (Fig. 4.2).

Since the start of the Syrian crisis in 2011, Lebanon received less humanitarian aid in absolute numbers than its neighbour Jordan , but more than Turkey, both of which also hosted very large numbers of Syrian refugees. However, Turkey received substantially more humanitarian aid per refugee compared to Lebanon and Jordan (Fig. 4.4). Between 2011 and 2016, Turkey received an average of just under $1,685 per refugee per year, while Lebanon received $287 and Jordan an average of $146 per refugee.

At $207 million, Lebanon also received less aid for health from 2011 to 2016 than Turkey ($223 million) and Jordan ($512 million). However, the three countries were comparable in the proportion of aid received for the health sector: 4% in Lebanon, 1% in Turkey and 4% in Jordan .

Non-development Assistance Committee Donors

In addition to aid provided by ‘traditional’ donors—members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC), e.g. the USA , Germany , the UK —humanitarian aid to the Syrian crisis is also provided by non-DAC donors. Non-DAC donors are any beyond the current 29 DAC members and typically refer to official country donors (i.e., bilateral) as well as private foundations. Some non-DAC donors report their data to the OECD’s Creditor Reporting System while others do not. As such, it is challenging to assess the magnitude of aid from non-DAC donors benefiting Syrian refugees in Lebanon.

The UAE is the largest non-DAC donor disbursing aid to Lebanon which reports to the CRS. From 2002 to 2016, UAE disbursed $33.7 million in humanitarian aid (1% of all humanitarian aid) and $12.4 million in health aid (3% of all health aid) to Lebanon. Other non-DAC donors reporting to the CRS include Kuwait, which disbursed 0.1% ($1.9 million) of total humanitarian aid to Lebanon over 2002–2016, and the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Companies (OPEC) Fund for International Development, which disbursed 0.3% ($1.1 million) of total health aid to Lebanon between 2002 and 2016. These non-DAC donors are captured within the analysis of aid to Lebanon above (Figs. 4.1, 4.2, 4.3 and 4.4).

Other non-DAC donors understood to be disbursing aid for Syrian refugees in Lebanon include other members of the Gulf Cooperation Council and Iran . In addition, aid to Lebanon is provided by local NGOs, philanthropic organisations, Islamic organisations, civil society organisations and Syrian refugee associations. There is little data available on the scale of contributions from these organisations. Much of their aid goes directly to partners instead of being channelled through the Syrian Regional and Refugee Resilience Plan (3RP). The 3RP, composed of eight sectors including Health, was launched in 2013 for the purpose of improving coordination of the response, with the participation of more than 60 humanitarian implementing partners representing UN agencies, international non-governmental organisations (INGOs) and local NGOs (LNGOs) (3RP 2017).

Limitations

There are limitations inherent in our approach to tracking aid flows for Lebanon. CRS data is widely used when tracking aid for health, as the main publicly available source of data on aid disbursements (Pitt et al. 2018; Grollman et al. 2017). The CRS provides access to data on all main donors of ODA over a long time period. However, there are limitations inherent with using CRS data. Firstly, currently the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is the only private foundation that report to the CRS, so the data used do not capture other sources of private grants supporting the health and humanitarian sectors in Lebanon. Secondly, it is challenging to produce robust estimates of aid flows to a country such as Lebanon, with an integrated refugee population, which uses local education and health services. There is not a clear delineation between aid to the health sector supporting only the Lebanese population and aid to the refugee population. Likewise, aid to the humanitarian sector can actually be supporting health activities for the host population. Finally, to date there is not an accurate picture of the role of nontraditional donors for Lebanon. These may represent a substantial aid envelope for Lebanon, but lack of transparency of data on disbursements from nontraditional donors prevents such insights. Therefore, given the available data, our estimates are the best indication we have of aid flows to the health and humanitarian sectors in Lebanon.

Health Sector Response to the Syrian Crisis

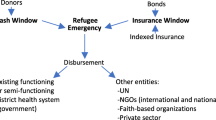

The health sector response in Lebanon involves a total of 24 national, international and governmental implementing agencies and is led by the Lebanon MoPH, WHO and UNHCR. The health sector coordinated response to the refugee crisis targets a population of over 1.5 million people out of a total of 2.4 million population in need (Inter-Agency Coordination Lebanon 2018). The populations targeted by the response plan include not only Syrian refugees but also Palestinian refugees settled in Lebanon or coming from Syria , as well as vulnerable Lebanese host communities. The health sector response lists the following four priority interventions: (1) ensuring access to target populations to a standardised package of basic health service at primary care level, (2) access to life-saving secondary care mainly for the Syrian displaced population, (3) preventing and controlling epidemic outbreaks in high risk areas with the largest number of Syrian displaced population and (4) reinforcing youth health as part of a comprehensive reproductive healthcare and through the school health programme (Ministry of Public Health (MPH) and WU 2015).

Healthcare for all Displaced Syrians in Lebanon

In Lebanon, primary healthcare is available to Lebanese as well as displaced Syrians (i.e. whether registered or unregistered with UNHCR), through a variety of primary healthcare facilities. The Lebanon Crisis Response Plan (LCRP) 2017–2020 set financing arrangements to strengthen and enhance the resilience and capacities of the health system in responding to primary, secondary and tertiary healthcare needs of displaced Syrians, Palestinian refugees from Syria and the most vulnerable in the host communities of Palestinian refugees and Lebanese in Lebanon. According to the LCRP Health sector strategy, subsidised primary healthcare is available to both registered and non-registered Syrian refugees (Ministry of Public Health (MPH) and WU 2015). Primary healthcare includes the following services: vaccination, medication for acute and chronic conditions, non-communicable diseases (NCD) care, sexual and reproductive healthcare , malnutrition screening and management, mental healthcare, dental care, basic laboratory and diagnostics as well as health promotion. Most of these services are provided to Syrian refugees in 111 primary healthcare facilities (including 62 MoPH-PHCCs and 49 dispensaries including 13 Lebanese Ministry of Social Affairs (MoSA) social development centres) (Ministry of Social Affairs Lebanon and UNHCR 2018) for a nominal fee compared to private clinics. Services are delivered with the support of international and local partners to reduce out-of-pocket expenditure, in light of the high economic vulnerability levels of displaced Syrians. Subsidised care is available to a number of vulnerable Lebanese as a way of addressing critical health needs and mitigating potential sources of tension in nearly 75% of the aforementioned facilities. From January to September 2017, approximately 1,058,412 subsidised consultations were provided at the PHC level by LCRP partners, out of which data for Syrian refugees have not been disaggregated, but 17% were consultations for vulnerable Lebanese (Ministry of Social Affairs Lebanon and UNHCR 2018).

In addition to LCRP partners, other organisations, e.g. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) Switzerland and MSF-Belgium, provide a number of free PHC services for displaced Syrians, vulnerable Lebanese as well as other population groups. From January to August 2017, MSF-Switzerland and MSF-Belgium provided approximately 225,000 additional consultations, representing an additional 21% of the caseload supported by LCRP partners (Ministry of Social Affairs Lebanon and UNHCR 2018). MSF-Belgium also offers free delivery care for Syrian refugees with very high demand.

In parallel to the provision of PHC services through MoPH PHCCs and dispensaries, specific primary healthcare services are also made available to displaced Syrians through approximately 25 mobile medical units (MMUs), operated by various NGOs, which provide free consultations and medication and often refer patients to PHCCs for services unavailable at MMUs. Though fewer in number than at the onset of the Syrian crisis, MMUs continue to be operational primarily in areas with high distribution of informal settlements and/or in distant rural areas from which PHCs are hard to reach. From January to September 2017, approximately 216,266 free consultations were provided through MMUs by LCRP partners representing an additional 17% of the total consultations supported by LCRP partners (Ministry of Public Health (MPH) and WU 2015). Meanwhile, primary healthcare services are also widely available to displaced Syrians through private doctors’ clinics, pharmacies or even hospitals, although these services are much higher in cost, leading to higher out-of-pocket expenditure. Medical services are also available to the displaced population through numerous informal practices run by Syrian doctors or midwives in informal settlements (Syrian Refugees 2014).

Healthcare for Syrian Refugees Registered with UNHCR

To facilitate the process of providing healthcare to registered Syrian refugees, UNHCR contracts a third-party administrator (TPA), including a range of governmental and non-governmental administrators. The TPA is the link between registered Syrian refugees and the facility where they receive healthcare. The TPA contracts a network of public and private hospitals throughout the country where refugees can access care. Inclusion in this network is decided by UNHCR based on proximity to beneficiaries, availability of services and cost-effectiveness. As a general rule, UNHCR does not support care given in hospitals outside of the network.

UNHCR supports provision of referral care to Syrian refugees through a cost-sharing mechanism. The TPA agrees with the contracted hospital on standardised fees following MoPH fixed rates. Since July 2018, for bills between $101 and $2900, UNHCR requires Syrian refugees to pay $100 in addition to 25% of the remaining hospital bill. For bills of $2900 and above, Syrian refugees pay $800 (UNHCR 2018a). The remaining bill is directly paid by UNHCR, conditional on Syrian refugees retaining and submitting the bill for payment. Syrian refugees who are unable to pay their share are not able to receive care.

UNHCR has specified $10,000 as the maximum total cost for a single hospital admission and does not reimburse bills exceeding this amount (UNHCR 2018a). For certain types of care, e.g. neonatal intensive care and burns intensive care, the maximum amount is extended to $15,000. The maximum total amount that UNHCR will provide for one single household during a year is $30,000. As a general rule, UNCHCR also mandates that governmental hospitals should be prioritised, and if not possible, then the most cost-effective alternative should be sought. Nonurgent cases are often ineligible for UNHCR support. To be declared eligible, a detailed medical report is needed accompanied by appropriate copies of medical investigations performed.

Affordability of Healthcare for Syrian Refugees

Affordability of healthcare has been identified as a major challenge for refugees in accessing healthcare (Ministry of Social Affairs Lebanon and UNHCR 2018). The 2017 vulnerability assessment survey showed that although displaced Syrians can, in theory, access primary healthcare services from a variety of health outlets, their main barrier to accessing services is reported to be cost-related (UNHCR 2017c). The survey found that of those Syrian refugee households that did not receive the required primary healthcare, the main reasons cited were cost of drugs (33%) and consultation fees (33%). Furthermore, out-of-pocket expenditure on health among displaced Syrians comprises 11% of total household expenditure (UNHCR 2017c). The financial cost of covering the healthcare expenses of the displaced Syrian population is reported to exceed by far the resources allocated by both international and national agencies (Ammar et al. 2016).

Meeting the cost of hospital care is challenging for Syrian refugees. Nearly one quarter (24%) of surveyed Syrian refugee households report requiring access to secondary or tertiary healthcare in the previous 6 months, of which one in five did not receive the required care, with 53% of surveyed households cited cost of treatment as the main barrier to accessing care (UNHCR 2017c). There are also reports of hospitals putting in place strategies to recover as much of the Syrian patients’ portions of the bills as possible by inflating bills, asking for deposits to be paid prior to admission and retaining corpses/displaced Syrian IDs or UNHCR registration documents until the hospital bill is settled, which raises protection concerns (UNHCR 2017c).

On the supply side, the impact of displaced Syrians on the Lebanese health system remains unparalleled, when examined in proportion to the country’s host population (Blanchet et al. 2016; Government of Lebanon and UNHCR 2018). Treating patients who are not able to pay has caused hospitals to accumulate a total debt of $15 million since the onset of the Syrian crisis, according to MoPH records for 2016. This debt has put an enormous stress on the public hospital system and its ability to provide services to Syrian refugees and vulnerable Lebanese (GoL & UN 2018; Ministry of Social Affairs Lebanon and UNHCR 2018). The limited financing of access to secondary care services has resulted in a major gap in service coverage, leading to a heavy financial burden on refugees seeking secondary and tertiary care services. Lebanese hospitals are seeing increased numbers of Syrian patients who are unable to pay their proportion of the bill, as well as Syrian patients whose hospitalisations are not subsidised. Referral of uncovered Syrian patients with complicated morbidities to public hospitals has also become a common practice by private hospitals, even though care at public hospitals is also not free but only subsidised by UNHCR for registered refugees (A. H. C. G. Report 2016).

Box 4.2 Spotlight: Financing Care to Syrian Refugee Women in Lebanon

Financial constraints limit Syrian refugee women’s access to healthcare. Antenatal care (ANC) constitutes an important proportion of medical services provided to Syrian women at primary healthcare level. However, a 2017 UNHCR study found that 73% of women aged 15–49 years and who had been pregnant in the past 2 years reported accessing at least one ANC visit, representing a 3% increase in access compared to 2016 (Government of Lebanon and UNHCR 2017). Among the 27% of pregnant women who did not receive ANC, 47% reported being unable to afford doctors’ fees. Moreover, only 28% of women who delivered reported receiving postnatal care (PNC), of which 22% said they could not afford the clinic fees. These findings demonstrate the need to increase uptake of ANC and PNC by displaced Syrian women and address financial barriers.

With regard to family planning, a recent study on the barriers to contraceptive use among Syrian refugees points to cost as the main reported barrier to contraceptive use (UNDP and ARK 2017; Masterson et al. 2014). These findings are echoed by implementing agencies who report a contributing factor as the inconsistent implementation of the official communication of the MoPH related to reproductive health services at MoPH-PHCC level, which both places a ceiling on the cost of reproductive health services and emphasises that family planning commodities are to be distributed free of charge (Government of Lebanon and UNHCR 2018).

Assessing the current health status and healthcare utilisation of Syrian women in Lebanon is challenging due to lack of quality and quantity of timely data. However, a recent study assessing coverage of key evidence-based RMNCH indicators in displaced Syrian women reported that in 2015, out of all referrals for delivery, about one-third (33.7%) of Syrian refugee deliveries in UNHCR-contracted hospitals were Caesarean sections (C-sections) (DeJong et al. 2017). This is also due to the fact that Syrian women are delivering within a Lebanese health system where C-sections rates are high.

Another challenge to Syrian refugee women accessing care is the July 2018 revision to the UNHCR healthcare financing policy stipulating that compared to the earlier policy, only pregnant women who are registered with UNHCR before arriving at the health facility to deliver are eligible to receive financial support from the agency to cover partial delivery expenses (UNHCR 2018c). Pregnant Syrian women who are registered with UNHCR will be required to pay between $150 and 200 for a normal delivery and $225 and 355 for a C-section depending on which hospital they go to, with the understanding that UNHCR will pay the remaining bill if the receipt is retained by the patient. Women who have not already registered with UNHCR will be required to pay the entire hospital bill. Women in need of additional hospital care other than for their delivery are required to pay $100 more than the previous UNHCR policy (UNHCR 2018c).

Aid Planning and Coordination

UNHCR was given the leading role to coordinate and implement aid to refugees in Lebanon, which is commensurate with it being the second largest channel of health and humanitarian aid in Lebanon after UNRWA , which caters solely to Palestinian refugees. As part of this role, in 2013 UNHCR created a separate coordination platform that it coleads with MoSA representing the Government of Lebanon. The multisectoral 3RP launched in 2013 with more than 60 humanitarian implementing partners aims to also address host community inclusion and create livelihood opportunities via the introduction of new programmes and the enhancement of governmental institutions capacities (3RP 2017). As part of the coordination mechanism, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) monitors gaps and coordination issues among the UN agencies, UNDP coordinates development projects and WFP conducts the annual vulnerability assessment surveys to improve beneficiary targeting.

Funding Levels

Mobilising adequate funding has been a major impediment to the response to the refugee crisis in Lebanon (Fig. 4.5). In 2018, delays in funding were reported to have led to discontinuing financial coverage of pregnant women in Palestine refugees from Syria and resulted in serious shortages of medication for chronic conditions at medical facilities supported by MoPH (Inter-Agency Coordination Lebanon 2018).

Health sector funding status in Lebanon, 2013–2017 (UNHCR 2018b)

Lack of sufficient funding for healthcare in the eighth year of the Syrian crisis poses grave challenges to agencies tasked with delivering services to Syrian refugees. In 2017, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF ) appeals to keep basic services functioning for $1.4 billion received less than 25% of its funding requirements, while the UNHCR 3RP appeals seeking $4.63 billion to also only cover essential services received $433 million, i.e. 9% of the request (United Nations Refugees and Migrants (UNRM) 2017; UNHCR 2017b, c). At a donor conference for Syrian refugees hosted in Brussels in 2019, UNHCR appealed for aid citing that the funding gap is leaving Syrian refugees, particularly women and children (over 70% of the refugee population), with substantial cuts in services and a lack of resources to address their growing needs but fell $1 billion short of its target (European Council 2019). In Lebanon, in 2017 UNHCR faced an underfunding of $11.7 million for secondary healthcare needed to reach a minimum of 5000 people per month. Similarly, UNICEF reported it needed $4.7 million to provide child health and nutrition care to 500,000 children under the age of 5 years (3RP 2017).

Evolving Use of Cash-Based Interventions to Deliver Aid to Syrian Refugees

While aid to refugees has traditionally been provided through in-kind contributions, such as shelter and hygiene kits and the direct provision of healthcare services, cash-based interventions have been used increasingly in recent years (see also Chap. 3 “Innovative Humanitarian Health Financing for Refugees”), especially in Lebanon. Cash-based interventions include both unconditional and multipurpose cash transfers, cash transfers with eligibility conditions (including cash for work) and vouchers that can be exchanged for specific items, services or cash. The humanitarian communities in Lebanon, including donors, have been increasingly relying on cash-based interventions—rather than in-kind basic assistance—as a way of delivering assistance to the affected population in Lebanon as part of the Syria response since 2013. For example, food assistance provided by World Food Programme (WFP) has evolved from in-kind support to paper food vouchers and then to electronic cards in 2016 for use in designated shops across Lebanon. As donor appetite for multipurpose cash assistance (MPCA) has grown, cash-based interventions have evolved in Lebanon and have included a wide range of activities across various sectors, including shelter, education, protection, WASH, food security and basic assistance. Considering that Lebanon is a country with well-functioning and elastic markets with a range of goods and services available, cash has been determined to be an appropriate modality to enable every household to prioritise their individual needs. With the Syrian refugee population spread across the country, living in different shelter types and with different needs and priorities, cash offers a flexible solution that enables families to choose for themselves how to address their prioritised needs in a dignified manner.

Despite these advantages, cash has not been deemed by humanitarian actors as a ‘silver bullet’ and is instead one component of a wider response in which other humanitarian actors have sought to ensure availability and accessibility of quality services such as health, education and water supply for all. Reflecting on the different needs that voucher and cash-based interventions were being used to deliver, six international NGOs delivering assistance in Lebanon opted to form the Lebanese Cash Consortium (LCC) and to develop and roll out a ‘multipurpose’ cash approach to socio-economically vulnerable Syrian refugee households in Lebanon from 2014. Members of the LCC are Save the Children (Consortium Lead), the International Rescue Committee (Monitoring and Evaluation and Research Lead), ACTED, CARE, Solidarités and World Vision International. This consists of a single transfer that is intended to cover multiple survival needs of a refugee family. After the development of the Survival Minimum Expenditure Basket (SMEB) among cash actors in 2014, an appropriate transfer value was set at $175 per family per month, which has been deemed to be the gap in a family’s needs that could not be met through the family’s own means or through food assistance, and continues to be provided by WFP. Figure 4.6 provides an overview of programme delivery steps of the LCC’s MPCA.

Key programme delivery steps of the Lebanese Cash Consortium’s multipurpose cash delivery (International Rescue Committee 2014)

Findings from the most recent vulnerability assessment survey in 2017 (UNHCR 2017c) show that economically vulnerable Syrian refugees continued to receive cash and other types of help including household items, education, subsidised healthcare and shelter assistance. Seventy-one percent of the sampled population reported receiving some form of assistance in the three months prior to the survey. Food assistance delivered by WFP through a common cash card makes up the largest proportion of assistance to Syrian refugees. The level of assistance was maintained at $27 per person per month, and in May 2017, WFP provided food assistance to 692,451 Syrian refugees, which is an increase of over 14,000 refugees compared to June 2016. Compared to food and other assistance, MPCA is delivered to fewer Syrian refugees as it aims to assist the most socio-economically vulnerable households, selected based on predefined criteria, in meeting their basic needs. In May 2017, 29,581 Syrian refugee households were receiving multipurpose cash from UNHCR, and other cash actors were providing multipurpose cash assistance to an additional 17,874 households (UNHCR 2017c). In addition, just over one-third of surveyed Syrian households reported receiving seasonal cash assistance during the winter cycle in 2016–2017 (UNHCR 2017c). The same survey reported 72% of children and youth aged 5–24 currently attending school received some type of school-related support in the 2016–2017 academic year (UNHCR 2017c).

An impact evaluation of the LCC MPCA found that it increased refugees’ consumption of living essentials, including food and gas for cooking. Syrian refugees’ total monthly expenditures, which include food, water, health, hygiene and other consumables, were on average 21% higher than those of non-beneficiaries (Lebanon Cash Consortium (LCC) 2016). From a social cohesion perspective, LCC beneficiaries felt eight times more secure, as compared to non-beneficiaries. In addition, LCC MPCA appeared to increase by five times Syrian refugees’ sense of trust of the community hosting them (Lebanon Cash Consortium (LCC) 2016).

Implications for Research and Practice

Lebanon has the highest per capita density of refugees in the world, with three quarters of this population comprising women and children and the majority under 19 years old. This large refugee population has placed critical strain on the country’s economy and public services, including the health system. A complex financing environment exists for displaced Syrians in Lebanon as a result of a high level of health service provision from the private sector, high out-of-pocket expenditure on health services and an increasingly constrained funding landscape (see also Chap. 3 “Innovative Humanitarian Health Financing for Refugees”).

We found that aid to humanitarian and health sectors comprised 28% of all aid to Lebanon between 2002 and 2016. In total, $3.2 billion has been disbursed to Lebanon in both humanitarian and health aid over this period. Clear peaks in humanitarian aid are identifiable in 2012 and 2015, in line with the start (in 2011) and then intensification of the Syrian crisis. These peaks in humanitarian aid were largely driven by disbursements from the USA . Since 2014, Germany and the UK have also become significant donors of aid to Lebanon. Aid to Lebanon has largely been channelled through three organisations—UNRWA , UNHCR and UNICEF . Lebanon has received more total humanitarian aid between 2002 and 2016 than its neighbours Turkey and Jordan , which also host Syrian refugees.

Despite the aid received by Lebanon, the difficulty of mobilising adequate funding has significantly impeded the response to the refugee crisis. The 2017 UNHCR appeal to fund the 3RP received just 9% of the $4.6 billion requested to provide essential services. This funding gap is having a critical impact on Syrian refugees’ access to care and well-being in Lebanon, particularly that of women, children and adolescents who comprise the majority of the Syrian refugee population. Cash-based interventions are increasingly being used in Lebanon to deliver both aid and health services to displaced Syrians, in combination with subsidised private sector and free public sector primary health services. A significant gap in coverage is evident in the provision of secondary and tertiary care where subsidies are proportionally much smaller than for primary care, placing the financial burden on refugees requiring this level of care. This is particularly challenging given the protracted nature of the Syrian crisis and that humanitarian agencies have had to reduce their subsidies since July 2018. Displaced Syrians report that costs are the main barrier to accessing health services, and their out-of-pocket expenditure is high. In particular, Syrian women are facing increased financial constraints, for example, as a result of recent policy revisions by UNHCR regarding eligibility for subsidised delivery care for pregnant Syrian women.

Findings from our chapter highlight the challenges of integration for host and refugee populations alike in Lebanon. The country’s non-encampment policy is one of few models of deliberate integration of refugees with the host population. It contrasts with Jordan’s encampment policy and the UNRWA model for Palestinian refugees. However, it presents similarities with Turkey’s refugee policy, which provides its 3.6 million Syrian displaced population (3RP 2019) temporary protection to access services in the national system alongside Turkish nationals, and Uganda’s integration policy which offers access to domestic health services to its 1.3 million refugee population, the majority (64.9%) of whom are from South Sudan (UNHCR 2019). Nevertheless, in proportion to its total population, the impact of the Syrian population on the Lebanese health system remains unparalleled (Blanchet et al. 2016; Government of Lebanon and UNHCR 2018). Integrating displaced Syrians with host Lebanese populations has several potential benefits including fostering sustainability without the need to set up parallel systems for health, education, etc. However, integration also raises distinct challenges for refugees and host populations that arise with their mixing, such as barriers to access to secondary care, high out-of-pocket expenditures, variable access to cash-based incentives and basic care needs which are not met for a proportion of refugees and vulnerable Lebanese. Furthermore, these issues pose a threat to Lebanon’s integration model, as the immigration of Syrian refugees has had a substantial impact on the country’s health system and on low-income Lebanese. For example, overburdening hospitals and health facilities eventually limits care for both the refugee and local population and has led to tensions (APIS Health Consulting Group 2016). Similar challenges are also seen in countries like Turkey where refugees have experienced an increase in out-of-pocket expenditures and challenges in accessing healthcare, while pressure on the health systems has been growing (Samari 2015; Chong 2018; 3RP 2019).

Our literature review and aid analysis highlight several limitations including gaps in data (see also Chap. 9 “The State of the Art and the Evidence on Health Records for Migrants and Refugees: Findings from a Systematic Review”). Firstly, data on domestic financing in Lebanon have not been accessible since 2006, which makes it challenging to understand whether financing arrangements are effective and efficient. Secondly, data on coverage of key interventions for women, children and adolescent refugees are mostly unavailable. These data gaps mean that we have a very incomplete picture of the RMNCH among the whole population of refugees, because of difficulties in sampling given the mobility of refugee populations and the absence of a sampling frame (DeJong 2017, DeJong et al. 2017). Using population as a denominator to calculate coverage of interventions for both host and refugee populations in Lebanon is also challenging because the last census in Lebanon was conducted in 1932, the refugee population is highly mobile and estimates of displaced Syrians in Lebanon are difficult to determine and fluctuate. Thirdly, recent health system data in Lebanon are not available in the public domain, making it difficult to assess health system functionality and to measure the impact of the Syrian crisis on the Lebanese health system. Fourthly, the Syrian refugee and funding situation remains very fluid. To paint a full picture of the situation, this chapter has had to combine data from different years and of different forms. For example, coverage rates of health interventions vary over time according to financing and which health services are funded over time and to what level vary substantially, such as in the case of delivery of care as described earlier.

This chapter also highlights significant gaps in research. To date, there are no comprehensive published studies on the cost-effectiveness of cash-based incentives and their effect on intended outcomes (e.g. health and nutrition) for refugees in Lebanon. Additionally, in terms of estimating coverage rates for RMNCH and other health-related interventions, it is unclear what the comparators for Syrian refugees should be, e.g. Syria pre-conflict or the Lebanese population. This comparator issue is one of the largest conceptual and methodological challenges researchers face when working on refugee populations in all settings (DeJong 2017). Finally, gaps in data and evidence underscore the importance of developing and supporting research capacity in Lebanon, as researchers in such countries are in the best position to collaborate with existing governmental and service providers to maximise the chances of generating relevant research findings that inform positive change in financing as well as provision of health services and programmes (DeJong 2017).

Our findings raise a number of questions for the future of displaced Syrians in Lebanon, as well as their impact on the country’s health system and low-income Lebanese populations. The future of financing and delivery of essential services, including RMNCH, for refugees in Lebanon is unclear taking into account increased funding cuts from international donors (e.g. the USA ) and grave underfunding of UNHCR. Furthermore, the US announcement of its withdrawal of aid from UNRWA in 2018 will have significant implications for the funding of refugees in Lebanon. The EU and Germany pledged their continued support for UNRWA and are urging other donor countries to do the same (Kitamura et al. 2018), but to date significant funding gaps remain. This systemic underfunding and the strain that the hosting of refugees has placed on Lebanon’s health system also have implications for low-income Lebanese populations and their access to essential services.

Our findings echo challenges increasingly being faced by other countries using an integrated health systems model for refugees such as Turkey and Uganda. The recent draft global action 2019–2023 on “Promoting the health of refugees and migrants” endorsed at the World Health Assembly in May 2019 notes that the entitlement of and access to health services by refugees and migrants vary by country and are determined by national law (World Health Organization 2019) (see also Chap. 13 “Global Social Governance and Health Protection for Forced Migrants”). It argues for a mainstreaming of refugee health in country agendas, as well as strengthening capacity of host countries and the provision of evidence-based health services delivery models. With humanitarian crises becoming both more commonplace and increasingly protracted, it is important to understand how an integrated approach to healthcare can be made more effective, efficient and sustainable and how to mitigate for unintended consequences of this model. Innovative models for financing of service delivery are urgently needed to ensure adequate provision of healthcare to refugees outside of the traditional, short-term and camp-based approach and in order to optimise equitable access to healthcare among both host and refugee populations.

Abbreviations

- 3RP:

-

Syrian Regional and Refugee Resilience Plan

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- CRS:

-

Creditor reporting system

- D:

-

Donor

- DAC:

-

Development Assistance Committee

- EU:

-

European Union

- GDP:

-

Gross domestic product

- IA:

-

Implementing agency

- INGO:

-

International Non-governmental Organisation

- LCRP:

-

Lebanon crisis response plan

- LCC:

-

Lebanese Cash Consortium

- LNGO:

-

Local Non-governmental Organisation

- MENA:

-

Middle East and North Africa

- MoPH:

-

Ministry of Public Health

- MoSA:

-

Ministry of Social Affairs

- MMU:

-

Mobile medical units

- MPCA:

-

Multipurpose cash assistance

- MSF:

-

Medecins Sans Frontières

- NGO:

-

Non-governmental organisation

- ODA:

-

Official development assistance

- OECD:

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- PHC:

-

Primary healthcare

- PHCC:

-

Primary healthcare centres

- PNC:

-

Postnatal care

- RMNCH:

-

Reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health

- TPA:

-

Third-party administrator

- UAE:

-

United Arab Emirates

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- UNICEF:

-

United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund

- UNFPA:

-

United Nations Population Fund

- UNHCR:

-

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

- UNOCHA:

-

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

- UNRWA:

-

United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East

- USA:

-

United States of America

- WFP:

-

World Food Programme

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

3RP. (2017). Regional Refugee & Resilience Plan 2017-2018 - 2017 annual report. Retrieved 10 September, 2018, from https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/3rp-regional-refugee-and-resilience-plan-2017-2018-response-syria-0

3RP. (2019). Turkey: 3RP country chapter - 2019/2020. Retrieved 14 June, 2019, from https://reliefweb.int/report/turkey/turkey-3rp-country-chapter-20192020-entr

A. H. C. G. Report. (2016). Syrian Refugees crisis impact on Lebanese Public Hospitals: Financial impact analysis: Generated problems and possible solutions.

Akala, F. A., & El-Saharty, S. (2006). Public-health challenges in the Middle East and North Africa. The Lancet, 367, 961–964.

Ammar, W., Kdouh, O., Hammoud, R., Hamadeh, R., Harb, H., Ammar, Z., et al. (2016). Health system resilience: Lebanon and the Syrian refugee crisis. Journal of Global Health, 6, 020704.

APIS Health Consulting Group. (2016). Syrian Refugees crisis impact on Lebanese Public Hospitals: Financial impact analysis: Generated problems and possible solutions. Retrieved 9 May, 2019, from https://www.moph.gov.lb/en/Pages/127/9287/syrian-refugees-crisis-impact-on-lebanese-public-hospitals-financial-impact-analysis-apis-report

Blanchet, K., Fouad, F. M., & Pherali, T. (2016). Syrian refugees in Lebanon: The search for universal health coverage. Conflict and Health, 10, 12.

Chong, C. (2018). Temporary protection: Its impact on healthcare for Syrian refugees in Turkey. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dejong, J. (2017). Challenges to understanding the reproductive health needs of women forcibly displaced by the Syrian conflict. The Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care, 43, 103–104.

Dejong, J., Ghattas, H., Bashour, H., Mourtada, R., Akik, C., & Reese-Masterson, A. (2017). Reproductive, maternal, neonatal and child health in conflict: A case study on Syria using Countdown indicators. BMJ Global Health, 2, e000302.

European Council. (2019). Supporting the future of Syria and the region - Brussels III conference, 1214/03/2019. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

Glasier, A., Gulmezoglu, A. M., Schmid, G. P., Moreno, C. G., & Van Look, P. F. (2006). Sexual and reproductive health: A matter of life and death. Lancet, 368, 1595–1607.

Government of Lebanon & UN. (2018). Lebanon crisis response plan 2017-2020 [Online]. Retrieved 20 September, 2018, from https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/63238

Government of Lebanon & UNHCR. (2017). Lebanon crisis response plan (LCRP) 2017-2020. Retrieved 8 July, 2018, from http://www.un.org.lb/lcrp2017-2020

Government of Lebanon & UNHCR. (2018). Lebanon crisis response plan 2017-2020 (2018 update). Retrieved 5 January, 2019, from https://reliefweb.int/report/lebanon/lebanon-crisis-response-plan-2017-2020-2018-update

Grollman, C., Arregoces, L., Martinez-Alvarez, M., Pitt, C., Mills, A., & Borghi, J. (2017). 11 years of tracking aid to reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health: estimates and analysis for 2003-13 from the Countdown to 2015. The Lancet Global Health, 5, e104–e114.

Inter-Agency Coordination Lebanon. (2018). Health dashboard Jan-April 2018.

International Rescue Committee. (2014). Emergency economies: The impact of cash assistance in Lebanon.

Janmyr, M. (2018). UNHCR and the Syrian refugee response: negotiating status and registration in Lebanon. The International Journal of Human Rights, 22, 393–419.

John Hopkins University (JHU), M. D. M., International Medical Corps, Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection, American University of Beirut and UNHCR. (2015). Syrian refugee and affected host population health access survey in Lebanon.

Kassak, K. M., Ghomrawi, H. M., Osseiran, A. M., & Kobeissi, H. (2006). The providers of health services in Lebanon: A survey of physicians. Human Resources for Health, 4, 4.

Kitamura, A., Jimba, M., Mccahey, J., Paolucci, G., Shah, S., Hababeh, M., et al. (2018). Health and dignity of Palestine refugees at stake: A need for international response to sustain crucial life services at UNRWA. The Lancet, 392, 2736–2744.

Lebanon Cash Consortium (LCC). (2016). Impact evaluation of the multipurpose cash assistance programme. Retrieved 10 September, 2018, from https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/library/impact-evaluation-multipurpose-cash-assistance-programme

Masterson, A. R., Usta, J., Gupta, J., & Ettinger, A. S. (2014). Assessment of reproductive health and violence against women among displaced Syrians in Lebanon. BMC Women’s Health, 14, 25.

Ministry of Public Health (MPH) & WU. (2015). Health: LCRP sector response plan.

Ministry of Social Affairs Lebanon & UNHCR. (2018). Lebanon crisis 2017-2020 (2018 update) response plan. Retrieved from http://www.LCRP.gov.lb

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2018). Paris, France. Retrieved 5 July, 2018, from https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=crs1

Pitt, C., Grollman, C., Martinez-Alvarez, M., Arregoces, L., & Borghi, J. (2018). Tracking aid for global health goals: a systematic comparison of four approaches applied to reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health. The Lancet Global Health, 6, e859–e874.

Salti, N., Chaaban, J., & Raad, F. (2010). Health equity in Lebanon: A microeconomic analysis. International Journal for Equity in Health, 9, 11.

Samari, G. (2015). Syrian Refugee Women’s Health needs in Lebanon, Turkey and Jordan and recommendations for improved practice. World Medical & Health Policy, 9(2), 255–274.

Sami, S., Williams, H. A., Krause, S., Onyango, M. A., Burton, A., & Tomczyk, B. (2014). Responding to the Syrian crisis: The needs of women and girls. Lancet, 383, 1179–1181.

Singh, N. S., Smith, J., Aryasinghe, S., Khosla, R., Say, L., & Blanchet, K. (2018). Evaluating the effectiveness of sexual and reproductive health services during humanitarian crises: A systematic review. PLoS One, 13, e0199300.

Syrian Refugees. (2014). Syrian health crisis in Lebanon. Lancet, 383, 1862.

UNDP & ARK. (2017). Regular perception surveys on social tensions throughout Lebanon: Wave I. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

UNFPA. (2018). Regional situation report on Syria crisis, Issue No. 72, July–August 2018. Geneva: UNFPA.

UNHCR. (2017a). Global trends, forced displacement in 2017. Retrieved 8 September, 2018, from http://www.unhcr.org/5b27be547.pdf

UNHCR. (2017b). UNHCR warns funding cuts threaten aid to Syrian refugees, hosts. Retrieved 9 September, 2018, from https://www.unhcr.org/uk/news/latest/2017/4/58e347288/unhcr-warns-funding-cuts-threaten-aid-syrian-refugees-hosts.html

UNHCR. (2017c). Vulnerability assessment of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon 2017. Retrieved 12 December, 2018, from https://reliefweb.int/report/lebanon/vasyr-2017-vulnerability-assessment-syrian-refugees-lebanon

UNHCR. (2018a). Guidelines for referral health care in Lebanon: Standard operating procedures. Retrieved https://data2.unhcr.org/es/documents/download/64586

UNHCR. (2018b). Lebanon - Syria Regional Refugee response. Retrieved 9 October, 2018, from https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/syria/location/71

UNHCR. (2018c). Q&A on UNHCR emergency healthcare new coverage and on support for birth deliveries for refugees in Lebanon. Retrieved https://www.refugees-lebanon.org/uploads/poster/poster_152993684592.pdf

UNHCR. (2019). Uganda comprehensive refugee response portal. Retrieved 14 June, 2019, from https://data2.unhcr.org/en/country/uga

United Nations. (2014). Report of the secretary-general on women and peace and security. Retrieved http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2014/693

United Nations Refugees and Migrants (UNRM). (2017). UNICEF-backed projects for millions of children in Syria on verge of being ‘cut off’. Retrieved 10 September, 2018, from https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/unicef-backed-projects-millions-children-syria-verge-being-cut

WHO. (2006). Health action in crises: Lebanon. Retrieved http://www.who.int/hac/crises/Lebanon_Aug06.pdf

World Bank. (2017). The toll of war: The economic and social consequences of the conflict in Syria. Washington DC: World Bank.

World Health Organization. (2019). Promoting the health of refugees and migrants: Draft action plan, 2019–2023 [Online]. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA72/A72_25-en.pdf

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Singh, N.S. et al. (2020). Healthcare Financing Arrangements and Service Provision for Syrian Refugees in Lebanon. In: Bozorgmehr, K., Roberts, B., Razum, O., Biddle, L. (eds) Health Policy and Systems Responses to Forced Migration. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33812-1_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33812-1_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-33811-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-33812-1

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)