Abstract

Conflicts are incorporated in any company’s business activity. The development of company’s international operations entails higher probability of conflict situations with foreign partners. The aim of the paper is to analyse the sources of conflict in inter-organisational foreign relationships of multinational enterprises (MNEs) and to identify how these conflicts affect MNEs’ activities. The outcomes are analysed both for inter-organisational relationship and for MNE’s activities in general. Also, formal and informal actions undertaken by managers in order to resolve a conflict situation and to minimise potential negative consequences are investigated. The analysis is based on in-depth interviews conducted in five different units (headquarters and subsidiaries) of Polish-based MNEs. After internal and comparative analysis, obtained results are compared with the existing research. The results show that identified conflicts in foreign inter-organisational relationships of MNEs’ units were not severe. The conflicts had sources mainly in everyday problems or cultural differences. Regardless of the source, in the majority of analysed MNEs’ units, conflicts had a positive effect on the external relationships themselves and the MNE’s activities.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Companies are forced to cooperate with various business entities. Among the numerous characteristics of the cooperation and inter-organisational relationships next to the complexity and long-time orientation, conflict is mentioned [16]. Being an inherent part of both social and business interactions [22], conflicts are inevitable. They manifest themselves with a different intensity—from marginal, such as everyday problems, to severe, posing a threat to the existence of the relationship or the company itself [19]. For companies, the importance of conflicts in relationships is high. Conflicts affect current and long-term management and require appropriate actions and then result in outcomes for a given inter-organisational relationship as well as the company itself. As far as these outcomes are concerned, existing research emphasises the negative consequences of conflict situations [14]; however, there are also studies underlining that conflicts can positively affect the relationship and a company’s activity [7, 23].

In international business activity, conflicts are more frequent and more unavoidable. The risk and intensity of conflicts in business relationships involving foreign business entities are higher than in relationships with domestic ones [22]. This is mainly due to cultural differences between markets and the geographical distance. This is an important statement as the research of conflict in international relationships of cooperation is limited (exceptions include, e.g. [22, 28]). The business entities that are important players in the international arena are multinational enterprises (MNEs). MNE may be defined as ‘a group of geographically dispersed and goal-disparate organizations that include its headquarters and the different national subsidiaries. Such an entity can be conceptualized as an inter-organizational network that is embedded in an external network consisting of all other organizations such as customers, suppliers, regulators and so on, with which the different units of the multinational must interact’ [9, p. 603]. Being present in foreign markets MNEs cooperate with entities that come from different cultural or economic backgrounds. The multitude of relationships maintained by MNEs with different business entities highly increases the probability and diversity of conflict situations within inter-organisational relationships. However, insightful research on conflicts in the cooperation relationships of MNEs is limited (exceptions include, e.g. [13, 27]).

For this reason, the aim of this paper is to analyse the sources of conflict in inter-organisational foreign relationships of MNEs and to identify how these conflicts affect MNEs’ activities. When identifying outcomes of conflict situations, we focus on outcomes affecting both the given inter-organisational relationship as well as MNEs’ activities in general. Additionally, we analyse formal and informal actions undertaken by managers in order to resolve a conflict situation and to minimise potential negative consequences. Our intention is to contribute to the existing research and broaden the analysis on inter-organisational conflicts in MNE’s foreign relationships by identifying the origin of conflicts as well as suggesting actions to be taken in order to handle conflicts in a positive (from the MNE’s point of view) way.

We base our analysis on in-depth interviews conducted in five different units (headquarters and subsidiaries) of Polish-based MNEs. The qualitative analysis allows us to qualify the results with real-life illustrations of conflict situations encountered by managers. The analysed conflicts concerned inter-organisational relationships between MNE units (headquarters or subsidiaries) and their foreign customers or suppliers. This is especially important in the face of calls for more research on vertical coopetition that is the cooperation and competition between a seller and a buyer [12, 18].

In the paper, we present a literature review in which we focus on sources and outcomes of conflicts in inter-organisational relationships. Since the research on conflict situations in inter-organisational relationships of MNEs is limited, we first analyse conflict situations in general and underline the research from international business. Then, we discuss results of the research concerning conflicts from the perspective of MNEs. In the next sections of the paper, after discussing the method of the study, we present an analysis of in-depth interviews conducted with the managers of units of five different MNEs and discuss the results. The paper finishes with conclusions in which we draw attention to potential future research.

2 Literature Review

Inter-organisational relationships are characterised by cooperation as well as by competition. Companies collaborate in order to generate a higher mutual value and compete in order to seize the greater amount of this value [6]. The simultaneous pursuit of cooperation and competition [6, 20] constitutes a challenge for companies since ‘the external forces or motives to compete and cooperate are seldomly balanced’ [20, p. 189].

The most dominant perspective in the literature on coopetition is studied among business entities from the same value chain level, mainly competitors. Here, coopetition may occur at inter-individual, inter-organisational and intra-organisational level [6, 20]. However, this view towards analysis calls for changes of perspective. As Lacoste [12, p. 649] underlines: ‘the ‘coopetition’ approach is often restricted to ‘horizontal’ relationships […], and there is little academic research applying the concept to ‘vertical’ relationships, e.g. between customers and suppliers’. The horizontal relationships embrace the cooperation with competitors, while vertical relationships include coopetition between entities acting as buyers and sellers or customers and suppliers [12, 18].

Tensions are an inherent part of coopetition [20]. It is therefore important to manage or to maintain and balance the cooperation and competition within buyer-supplier relationships [5, 6]. When entities are not able to manage or balance these tensions, they may, in turn, have an impact on the inter-organisational relationship and lead to conflict. Conflict may arise as the effect of action taken or not taken by another entity as well as the effect of interaction or the avoidance of interaction [13]. Therefore, they are an inherent part of every business activity, and every business cooperation involves tensions or differences which may lead to conflict situations [22]. These conflicts may have a different intensity—from day-to-day problems to very severe ones, which may result even in the relationship termination [13, 19].

Relationships between buyers and sellers, due to their common but at the same time opposing goals, are characterised by coexistent collaboration and competition which increase the probability of conflict situations [4]. Other sources of conflict include power, interdependency [28], misalignment of interests or mutual inability to adapt [2, 7]. Conflicts can also be triggered by social ties [16], misunderstandings and problems in communication [2].

Conflicts in international activity can also result from cultural differences and psychic distance [26]. As pointed out by Skarmeas [22, p. 565], ‘managing international trade relationships is a more challenging task compared with exchanges in the domestic context, due to geographical and cultural separation between exchange partners’. Although some studies do not confirm these results (e.g. [17]), cultural distance may sometimes inhibit the conflict handling in the relationship and even lead to the termination of cooperation [26, 28]. Some negative effects of relationship termination are visible, e.g. worse financial results, while others remain largely invisible, e.g. switching costs, lost market opportunities and reputation [23].

With respect to other undesirable outcomes, conflicts have been shown to have a negative impact on such aspects of the relationship as commitment [14]. Conflicts can also impede the development of relationships [15] or the company’s foreign activities. As Duarte and Davies [2, p. 91] state, there is a dominant assumption that ‘all other factors being equal, relationships where conflict is low will outperform relationships where conflict levels are higher’.

Interestingly, the impact of conflicts is not always negative—in some situations, they can positively affect the relationship and the company’s activity. Vaaland [24, p. 447] states that conflicts ‘provide the parties with insight into the core of the relationship, increase relational sensitivity, and as a result of these, insights restore the ability to manage a relationship under pressure’. Conflicts can strengthen a relationship [23]. Conflicts may also provoke discussions and decisions that aim at better coordination and performance [29] and also performance in inter-organisational relationships [7].

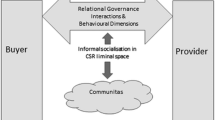

Given their potentially different outcomes, conflicts can therefore be damaging and beneficial at the same time [7, 25]. According to Koza and Dant [11], conflicts are more likely to have positive outcomes if they occur in the conditions of cooperative orientation and trust-based governance. These factors facilitate mutual communication between the business entities involved and make them better prepared for unknown and unplanned situations. Another important factor which increases the chances of a positive conflict resolution is the ‘willingness to find a mutually satisfactory agreement’ [21, p. 82]. It is also stressed that a conflict can have positive outcomes when it is managed with a certain degree of assertiveness on the part of the entities involved, who seek to satisfy their own goals during the cooperation [8]. The above actions may be classified as formal or informal ways of conflict handling. The formal ways of conflict handling are based mainly on formal agreements and reference to procedures, while the informal ways rely, for example, on inter-personal contacts or meetings [19].

To the best of our knowledge, the existing literature lacks in-depth analysis of conflicts from the MNE’s perspective. The analysis of conflict situations concerning MNEs focuses mainly on internal conflicts (within the MNE’s different units). For example, Lauring et al. [13] focus on the antecedents for and the consequence of low-intensity inter-unit conflicts within MNEs, while Vahtera et al. [27] identify to which extent conflicts impact the identification of knowledge sources in MNEs. The research on inter- and intra-relationship conflicts is advanced by Nordin [15]; however, conflicts are analysed in a specific context of the alliance implementation process. The existing literature presents also other analyses of conflicts within MNEs; however, the conflict situations are mentioned as the effect of the main problem such as psychic distance [1].

3 Method

The study presented in the paper is of qualitative character as this kind of research is suitable for the analysis of inter-organisational relationships [3]. This approach enables an in-depth analysis of a research problem, although it does not allow the drawing of generalisation or statistical conclusions.

To maximise the information without referring to generalisations, we used a purposive sample [18]. We chose Polish-based units of MNEs (headquarters or subsidiaries), which were active in at least one foreign market. The detailed criteria under which we chose the sample included: (1) company size (employment more than 250 people), (2) company being part of a foreign multinational company (business unit or headquarters), (3) company being active in foreign markets and (4) presence of conflicts or problem situations in company’s foreign relationships. The chosen criteria ensured that analysed units belong to large MNEs and not small companies active only in one foreign market. Additionally, as some managers might have been reluctant to speak about problems in relationships with other business entities (as it is perceived as a weakness), by conducting in-depth interviews, we could obtain needed information concerning conflicts and problem situations that took place in the relationships.

In the paper, we present the results of in-depth interviews conducted in five units of different Polish-based MNEs. After representatives of five units have been interviewed, the empirical saturation point had been reached, meaning that last interview provided narratives similar to those that had been already gained. Each interview lasted between 1 and 2 h and was conducted with the company’s key informant. To ensure confirmability, [10] all the interviews were recorded with no objection by the interviewees, and notes were taken during the interviews. Afterwards, the recorded interviews were transcribed. Based on the transcriptions, we prepared interview protocols which were used as the basis for the preparation of the illustrative examples presented in the paper. After internal and comparative analysis, the results were compared with findings of existing research.

During the interviews, we examined the process of entering a new foreign market for which the key informant was responsible, and we asked the key informants about the most important business entities and inter-organisational relationships in that process as well as their opinion concerning the mentioned relationships. One of the characteristics describing the inter-organisational relationships was conflicts. In each of the five analysed units of MNEs, we identified one important foreign inter-organisational relationship with either a foreign customer or a foreign supplier described by conflict. Thus, the units of our analysis are conflicts in inter-organisational relationships with foreign customers or suppliers perceived from the MNE’s unit perspective. Key informants in their interviews did not refer to conflicts with competitors—we may assume that these entities were not important during a new, foreign market entry.

The main characteristics of the analysed units of MNEs are shown in Table 15.1.

4 Analysis and Discussion

4.1 Analysis

Table 15.2 summarises the identified conflicts in inter-organisational cooperation relationships of the analysed MNEs’ units. They concerned relationships with external customers (e.g. distributors) and in one analysed MNE relationship with an external supplier. In the analysis, we adopt a broad definition of conflicts—we consider that conflicts may manifest themselves with different intensity from day-to-day problems to very serious conflicts, which may threaten further cooperation or the existence of company itself [19]. The identified conflicts mostly arose from various everyday problems regarding operational activities, such as work standards or supply punctuality, financial problems and cultural differences.

Conflicts in three of the analysed inter-organisational relationships of MNE’s units were caused by different aspects of operational activities. These included everyday problems regarding product quality and supply punctuality (B, U, X). In these units, the negative situation was not seen as a conflict but rather as a problem—as one of the interviewees stated ‘there are always some problematic situations’ (U). The next source of conflicts was related to the financial aspects of cooperation. In one subsidiary (ZD), the conflict resulted from financial demands made by a foreign customer which was hard to accept by the MNE’s unit in question. In another headquarters (X), the conflict was caused by financial problems of a foreign customer. This customer was responsible for contacts with a very big retailer, and the conflict might have threatened the further existence of the MNE on that foreign market.

Specific to international activity were the different aspects of cultural differences which were listed as a source of conflicts, mainly in inter-organisational relationships with foreign customers (B, U, X, ZD) but also with the foreign supplier (Z). Three specific problems were identified in this respect. The first was the difference in attitudes to work and safety standards or work organisation (B, X, Z, ZD), which results from cultural differences (the differences were between Poland vs. Germany, China and Kenya). These problems and conflicts appeared in the internationalisation process despite the actions aimed at dealing with psychic distance and differences in business etiquette taken by MNEs before entering the market (X, Z). The actions were: language courses, business code workshops or hiring employees who spoke the local language and had knowledge about the foreign market. The second specific problem with a cultural background involved local final customers (U, the MNE makes products sold by distributors to final individual customers in Hungary): they wanted products with labels in Hungarian which meant extra costs for the MNE because the size of the target market was limited. This is an example of how indirect relationships (with individual customers) influence the conflict situation in direct inter-organisational relationships (with external customer—distributor). The third aspect concerned problems stemming from inter-personal relationships (ZD). The cooperation with local customer was initiated based to some extent on informal relationships. These informal relationships on the one hand helped to start the internationalisation on that specific market but on the other, they inhibited, for a short time, a positive, for the MNE, conflict handling.

The most frequently reported approach to handle conflicts in inter-organisational cooperation relationships was to take formal actions (B, X, Z). These actions included establishing new procedures or referring to existing ones (B, X), offering workshops on cultural differences (X), obtaining certificates confirming product quality (X) and introducing common work standards based on the organisational culture existing at the MNE’s headquarters (Z). The introduction of new procedures was vital to the expansion on the foreign market as the existing procedures were not acceptable to foreign customers, especially in terms of product quality or meeting the punctuality of deliveries (B, X). Other actions taken to handle conflicts were the organisation of workshops on cultural differences or on business etiquette. One of the analysed MNEs (X) introduced a workshop for the employees who were to work with the German customer and hired a German-speaking person in its headquarters to deal with that customer. With the development of the cooperation and the MNE’s presence on the German market, the company hired another German-speaking person in its headquarters and also employed a German native to work in Poland for this German customer. As the key informant stated (X): ‘German people like to talk in their native language—they appreciate this possibility’. The next approach in handling conflicts in inter-organisational foreign relationships concerned obtaining certificates of the product quality (X) which was the necessary condition to continue the cooperation on that foreign market. Key informants stated that other formal actions of conflict handling required the introduction of common work standards (Z). One of the reasons was that the MNE’s headquarters was in Sweden and the company’s organisational culture was aiming at achieving a commonly shared solution so as to obtain the ‘win-win’ situation. The key informant added (Z) that ‘the potential conflicts should be neutralised or prevented’.

Another approach to conflict resolution was to improve the atmosphere of cooperation by both partners making efforts to resolve the conflict and reach a compromise (U, X, ZD). This can be classified as more informal action towards conflict resolution. The interviewed key informants stressed the importance of common goodwill and determination to resolve the conflict. They were open to find a mutually positive solution that would be acceptable for both sides (U, X, ZD). According to one key informant (X), ‘one feature of a crisis is that when you get out of it, you are stronger’. Actions focused on improving the attitude to cooperation also included a willingness to learn (B, Z). In these MNEs’ units, the two key informants admitted that they relied on knowledge and developed competencies to be able to handle the conflict with external business entities in a positive way. These competences included mainly the ability to work in a culturally diversified environment with distinct business requirements. This focus on the development of employees involved extra costs, but was, however, perceived as an investment in their competences. As one key informant (Z) said: ‘any coexistence with other cultures causes an additional challenge in the form of bridging cultural differences’. In another MNE, the cooperation aimed at creating a new product that was the condition for staying on that foreign market (X). It incurred additional costs because the product was of the excellent quality but as the key informant said (X) ‘there were repair actions, there were costs, but we played fair and we may continue on that market’.

As already noted, most of the key informants and their MNEs’ units were dedicated to finding a solution and resolving the conflict so that it would not jeopardise further cooperation with their customers or suppliers. As was stated by one key informant (Z): ‘just as soon as the promised orders were forgotten, the turbulences and misunderstandings were forgotten just as quickly’. One of the common solutions for conflict handling was improving communication. As another key informant (X) stated: ‘communication has contributed to the fact that successes have been, despite all, achieved’. Many key informants stressed that another important element was a quick reaction to a conflict situation and a mutual willingness to handle it in order to obtain a positive solution (B, U, X, ZD). As was stated (B): ‘if problems are managed quickly and effectively, they do not have a negative impact on the cooperation and relationship between partners’.

The willingness to incur extra costs was identified as another way of handling conflicts in inter-organisational relationships of the analysed MNEs’ units (X, Z, ZD). Key informants were aware that due to additional costs that appeared during conflict and actions to handle conflicts in a positive way, the MNEs were able to sustain the relationships and continue internationalisation in a chosen, foreign market. The costs helped the MNEs’ development due to new product invention (X) or the increase in employee competences (Z). In one case, the extra costs were allocated for the increase of the customer’s operating costs in a foreign market (ZD).

The conflicts identified in the four analysed foreign inter-organisational relationships of MNEs’ units had mainly positive outcomes. As one key informant (X) summed up problems on a foreign market: ‘we have started nearly from nothing, and now, we have almost all the time a linear growth [on that market]’. In nearly all of the analysed MNEs’ units, they enabled the MNEs to strengthen their relationships with customers (B, U, X) or supplier (Z). According to one key informant (B): ‘a problem situation is an opportunity to check the partner, and partners do not run away from problems. On the contrary, they try to analyse the problem quickly and end the conflict’. However, in one unit of the MNE, the conflict did lead to the termination of the external relationship (ZD). It was caused by the mutual inability to meet the requirements—the MNE could not afford to fulfil the customer’s financial requirements, while the external customer was not able to expand the MNE’s activities on nearby markets. According to the key informant, the financial aspects of conflict were difficult to resolve since the cooperation was based rather more on informal relationships than on a formal basis. Additionally, the MNE’s unit and its partner were not equally engaged in the relationship and were not dedicated to resolving the conflict to the same extent. That is why MNE decided to end this external relationship.

With respect to the impact of conflicts in inter-organisational relationships on MNEs’ activities, the interviewed managers also reported positive effects. In their opinion, the conflicts had a positive impact on the development of their MNEs’ units (B, X). MNEs obtained new knowledge and competencies that enabled them to develop their own skills, working procedures or product standards and in effect be more competitive in the foreign market. The experience and know-how gained from the cooperation were afterwards used to further the MNE’s internationalisation process.

5 Discussion

The identified conflicts in foreign inter-organisational relationships of MNEs’ units were not severe: they were mainly triggered by everyday problems, supply punctuality or cultural differences. Regardless of the source, in the majority of analysed MNEs’ units, we have concluded that conflicts had a positive effect on the external relationships themselves and the MNE’s activities.

It can be argued that MNE units which operate in foreign, diversified markets are more aware of having a well-established corporate culture and formal procedures in place. It is likely that these elements helped these units handle conflicts in a positive way. Some interviewed managers actually admitted that faced with conflict situations, they acted according to procedures and took formal actions. With the formal approach to conflict resolution, a similar course of action is taken throughout the whole MNE’s internationally dispersed network of relationships, which may have a positive influence on its international activities. The existing literature on MNEs presents actions to be taken to handle conflict mainly on the inter-personal [13] or inter-unit level [27]. We have found that the analysed MNEs decided to take formal actions also at the inter-organisational level. The formal actions concerned introducing new or modifying existing procedures on inter-organisational cooperation, improving the quality of products offered to external entities and obtaining certificates confirming the product’s quality. The other formal actions consisted of modifying or implementing the new rules or common work standards of cooperation. These results confirm the previous research that actions including technical aspects are an important element of conflict handling [5]. In the analysed MNEs’ units, these formal actions were of special importance in conflict handling since MNEs often operate in markets that are culturally distant. Formal procedures, common rules of cooperation or work standards may prevent some potential conflict situations emerging from cultural or legal differences. Outcomes of the above-mentioned conflict handling actions were the increased level of mutual trust and the unit’s development and growth. In one case, the knowledge of product development and certificates gained on one market allowed the company to be more competitive on other foreign markets. Another important group of more informal actions undertaken by the MNE units to handle conflicts in inter-organisational relationships was related to knowledge management and ways of improving communication and learning. MNEs operate in markets that are characterised by different culture, language, a different approach towards the reliance on agreements or towards collaboration and relationship development. These elements result in attributing special attention to actions that support knowledge transfer between the different entities involved, both in a more formal but also informal way. In order to improve learning and communication, the analysed MNEs offered language courses or business etiquette courses for their employees. Another solution that MNEs undertook was hiring people with required competences (e.g. a native from the foreign market in the local MNE headquarters or people with language skills) to their units or headquarters. The next action related to knowledge management and learning was the introduction of a common organisational culture which aimed at the development of knowledge management tools. The analysed MNEs referred to local experts or invited employees and external entities to work together to solve the problem. The effects of these actions helped MNEs to improve communication and enhance learning. In effect, the key informants stated that the inter-organisational relationships were strengthened. In some cases, these actions prevented the relationship from ending and allowed further expansion on a foreign market.

The study showed that managers were aware of the need to handle conflicts in foreign inter-organisational relationships appropriately. This confirms previous research findings which indicate that a conflict can bring positive effects only when there is ‘managerial involvement aimed at reducing negative emotions in personal relationships, increasing abilities to resolve conflicts as tasks and encouraging open norms in resolving conflicts of tasks and processes’ [7, p. 1064]. Another important aspect of international business activities is cultural differences. They influence MNEs’ international development and impact the learning abilities on new markets [30]. MNEs and their units operate and cooperate internationally in many foreign markets and thus deal with a number of foreign business entities and run a higher risk of conflict. The interviewed key informants were aware of cultural differences and their possible negative impact on cooperation and foreign inter-organisational relationships. However, adaptation to the cultural environment was not always perceived as the right solution in which case cost analysis was used as a way of choosing the right course of action. MNEs as large organisations can sometimes afford to bear extra costs in order to resolve conflicts. However, as the example with cultural differences indicates, a MNE will only be willing to bear extra costs if this is likely to bring positive financial effects in the future.

Although it has been demonstrated in earlier studies that conflict has a negative impact on different characteristics of relationships (such as trust) between foreign entities [14], this tendency was not confirmed by the interviewed managers of MNEs’ units. On the contrary, the results show that properly handled conflicts may have a positive impact on trust and contribute to a strengthening of the inter-organisational relationship. The analysis also shows that, when properly handled, conflicts experienced by MNE units can have mostly positive effects on their relationships and international activities. The positive effects manifested themselves in most of the cases in the strengthening of inter-organisational relationships. Foreign entities could see that MNEs are making an effort to handle the conflict and to find a mutually beneficial solution which would prevent further problems in the cooperation. These actions helped MNEs to prevent potential problems linked to the culture and cultural differences during the further internationalisation process. Our analysis confirms the findings reported by Vaaland and Håkansson [25] and by Finch et al. [7], which indicate that conflict can increase the perceived value of the relationship. Conflicts described in our study helped partners to analyse the sources of conflict in foreign business relationships and to find ways of resolving them. The analysis revealed that in some situations, the termination of the relationship was thought to be the best solution. In that specific case, the MNE was trying to maintain this relationship as the market was promising, and the MNE had already made some investment in the relationship. It was possible only on a short-term basis. After some time, and in continuous conflict situations, the analysed MNE decided to end the relationship because it was unprofitable in the long term. However, it has to be emphasised that such a termination did not have a negative effect on the unit’s general development. This shows that sometimes termination of the relationship is the best solution to the problem.

6 Conclusions

The results of the study contribute to the existing, rather limited, body of literature by analysing sources and outcomes of conflicts occurring in foreign inter-organisational relationships maintained by units of MNEs and by identifying actions that can be taken in order to handle conflict in a positive way.

Our analysis has practical implications. It can be used to formulate recommendations for managers on how to handle conflicts in foreign relationships in order to reduce the negative consequences for both the MNE unit itself and the whole MNE. Cultural differences between business entities as well as operational problems are common sources of problems that MNEs encounter during their international activities. In order to diminish the negative impact of conflicts in inter-organisational relationships, managers can take formal actions, such as following rules and established procedures, or bear extra costs to resolve the problem. Another approach involves more informal strategies, such as making a joint effort to solve the problem, looking for a compromise or knowledge management including openness to learning. As the analysis shows, it is not always possible to achieve a positive conflict resolution, and in extreme cases, the termination of the inter-organisational relationship is the only possible option.

The presented analysis is not free of certain limitations which simultaneously set the directions for further research. The conducted study is of qualitative character that enables an in-depth analysis of the research problem, however, does not allow the drawing of generalisations. Thus, quantitative study would enable to formulate statistical conclusions. Another limitation is linked to the particular country setting of the analysed MNEs and their units. All of the analysed units were based in Poland, and we have conducted interviews only with Polish MNEs’ representatives. As the assessment of conflicts in relationships is at least partly constrained by the perception of particular individuals, we may assume that managers from units based in different counties could assess conflicts differently. This suggests that detailed single-case studies including interviews conducted with representatives of MNE’s several units and representatives of external business entities should provide more complex information on conflicts in business relationships. Because MNEs and their units, both headquarters and subsidiaries, maintain a diverse network of relationships in foreign markets, the risk of conflict is always high. Further research should, therefore, concentrate on a more detailed analysis of ways how to handle conflicts and their effects on relationships and on the international activities of MNE units. In particular, research should focus on investigating the differences in conflict-handling strategies within coopetitive relationships, especially how the type of coopetition (that is coexistence, cooperation, competition, coopetition) impacts the conflict handling and the outcomes for both business partners. Additionally, it would be useful to conduct more detailed single-case studies aimed at the analysis of internal conflicts within the MNE network and assessing them taking into consideration the different actions used to resolve them.

References

Avloniti, A., Fragkiskos, F.: Evaluating the effects of cultural and psychic distance on multinational corporate performance: a meta-analysis. Glob. Bus. Econ. Rev. 20(1), 54–87 (2018)

Duarte, M., Davies, G.: Testing the conflict–performance assumption in business-to-business relationships. Ind. Mark. Manage. 32(2), 91–99 (2003)

Easton, G.: Case research as a methodology for industrial network: a realist approach. In: Naudé, P., Turnbull, P.W. (eds.) Network Dynamics in Marketing, pp. 73–87. Pergamon Press, Oxford (1998)

Ellegaard, C., Andersen, P.H.: The process of resolving severe conflict in buyer-supplier relationships. Scand. J. Manag. 31(4), 457–470 (2015)

Eriksson, P.E.: Achieving suitable coopetition in buyer-supplier relationships: the case of Astrazeneca. J. Bus. Bus. Mark. 15(4), 425–454 (2008)

Fernandez, A.-S., Le Roy, F., Gnyawali, D.R.: Sources and management of tension in co-opetition case evidence from telecommunications satellites manufacturing in Europe. Ind. Mark. Manage. 43, 222–235 (2014)

Finch, J., Zhang, S., Geiger, S.: Managing in conflict: how actors distribute conflict in an industrial network. Ind. Mark. Manage. 42(7), 1063–1073 (2013)

Fu, P.P., Yan, X.H., Li, Y., Wang, E., Peng, S.: Examining conflict-handling approaches by Chinese top management teams in IT firms. Int. J. Conflict Manag. 19(3), 188–209 (2008)

Ghoshal, S., Bartlett, C.A.: The multinational corporation as an interorganizational network. Acad. Manag. Rev. 15(4), 603–626 (1990)

Guba, E.G., Lincoln, Y.S.: Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In: Denzin N.K., Lincoln Y.S. (eds.) Handbook of Qualitative Research, pp. 105–117. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA (1994)

Koza, K.L., Dant, R.P.: Effects of relationship climate, control mechanism, and communications on conflict resolution behavior and performance outcomes. J. Retail. 83(3), 279–296 (2007)

Lacoste, S.: “Vertical coopetition”: the key account perspective. Ind. Mark. Manage. 41, 649–658 (2012)

Lauring, J., Andersen, P.H., Storgaard, M., Kragh, H.: Low-intensity conflict in multinational corporations. Multinatl. Bus. Rev. 25(7), 11–27 (2017)

Leonidou, L.C., Talias, M.A., Leonidou, C.N.: Exercised power as a driver of trust and commitment in cross-border industrial buyer-seller relationships. Ind. Mark. Manage. 7(1), 92–103 (2008)

Nordin, F.: Identifying intraorganisational and interorganisational alliance conflicts—a longitudinal study of an alliance pilot project in the high technology industry. Ind. Mark. Manage. 35(2), 116–127 (2006)

Plank, R.E., Newell, S.J.: The effect of social conflict on relationship loyalty in business markets. Ind. Mark. Manage. 36(1), 59–67 (2007)

Pothukuchi, V., Damanpour, F., Choi, J., Chen, C.C., Park, S.H.: National and organizational culture differences and international joint venture performance. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 33(2), 243–265 (2002)

Rajala, A., Tidström, A.: A multilevel perspective on organizational buying behavior in coopetition–an exploratory case study. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 23(3), 202–210 (2017)

Ratajczak-Mrozek. M., Fonfara, K., Hauke-Lopes, A.: Conflict handling in small firms’ foreign business relationships. J. Bus. Ind. Market. (2018, in press)

Raza-Ullah, T., Bengtsson, M., Kock, S.: The coopetition paradox and tension in coopetition at multiple levels. Ind. Mark. Manage. 43(2), 189–198 (2014)

Rognes, J.K., Schei, V.: Understanding the integrative approach to conflict management. J. Manag. Psychol. 25(1), 82–97 (2010)

Skarmeas, D.: The role of functional conflict in international buyer-seller relationships: implications for industrial exporters. Ind. Mark. Manage. 35(5), 567–575 (2006)

Tähtinen, J., Vaaland, T.I.: Business relationships facing the end: why restore them? J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 21(1), 14–23 (2006)

Vaaland, T.I.: Improving project collaboration: start with the conflicts. Int. J. Project Manage. 22(6), 447–454 (2004)

Vaaland, T.I., Håkansson, H.: Exploring interorganizational conflict in complex projects. Ind. Mark. Manage. 32(2), 127–138 (2003)

Vaaland, T.I., Haugland, S.A., Purchase, S.: Why do business partners divorce? The role of cultural distance in inter-firm conflict behavior. J. Bus. Bus. Mark. 11(4), 1–21 (2004)

Vahtera, P., Buckley, P., Aliyev, M.: Affective conflict and identification of knowledge sources in MNE teams. Int. Bus. Rev. 26(5), 881–895 (2017)

Welch, C., Wilkinson, I.: Network perspectives on interfirm conflict: reassessing a critical case in international business. J. Bus. Res. 58(2), 205–213 (2005)

Wong, A., Wei, L., Wang, X., Tjosvold, D.: Collectivist values for constructive conflict management in international joint venture effectiveness. Int. J. Conflict Manag. 29(1), 126–143 (2018)

Zeng, Y., Shenkar, O., Lee, S.-H., Song, S.: Cultural differences, MNE learning abilities, and the effect of experience on subsidiary mortality in a dissimilar culture: evidence from Korean MNEs. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 44(1), 42–65 (2013)

Acknowledgements

The paper was written thanks to the financial support from Poland’s National Science Centre—Decision no. DEC-2013/09/B/HS4/01145. Project title: ‘The maturity of a company’s internationalisation and its competitive advantage (network approach)’ (project leader: Professor Krzysztof Fonfara).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Hauke-Lopes, A., Fonfara, K., Ratajczak-Mrozek, M. (2020). Conflicts in Foreign Inter-organisational Relationships of Multinational Enterprises. In: Zakrzewska-Bielawska, A., Staniec, I. (eds) Contemporary Challenges in Cooperation and Coopetition in the Age of Industry 4.0. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-30549-9_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-30549-9_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-30548-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-30549-9

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)