Abstract

Children’s perspectives in research are increasingly being sought on matters that are of relevance to them. Child-led accounts of their everyday lives often involve a researcher and children participating in conversations. Sometimes, however, when sensitive issues are raised, these conversations can take unexpected turns, even with researchers experienced in working with children as researchers or teachers. This chapter investigates what happens when video-stimulated accounts lead to an unintended dispute. A small group of girls (four to six years old) in an inner-city playground in Queensland, Australia, watch a video recording of themselves playing a pretend game of school. When the researcher asks about the girls to tell her what was going on, some members of the group use this opportunity to make complaints about others in the group regarding how the game was played, resulting in a dispute. Fine-grained analyses using the approaches of ethnomethodology and conversation analysis reveal children’s competence in managing this unfolding ‘crisis’ of sorts and the dilemma faced by the researcher, who moved between membership categories of being a researcher with ethical processes to follow, and her previous work as a teacher, with pedagogical interest to promote positive relationships. Analyses reveal children’s competence in managing this crisis which causes a breakdown of their relationship. Their competence included resisting answering the researcher’s questions and using the forum to raise issues that mattered to their own social agendas. As well, findings highlight the delicate positions researchers may experience when investigating sensitive issues, namely finding a balance between respecting children’s competence as research participants by continuing their line of questioning or restoring the social order and well-being.

Professional Reflection by Paula Robinson and Claire Lethaby

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The importance of children receiving timely support to talk about past traumatic events is well-known in psychological research, where the process is intended to prevent the possibility of post-traumatic stress developing (National Institute of Clinical Excellence [NICE], 2005). In relation to the natural earthquake disaster in Christchurch New Zealand (February 2011), one such recovery strategy is ‘Respond, Renew Recover’, where the ‘Recover’ phase involves talking and recalling experiences in order to come to terms with the event (Brown, 2012). This chapter reveals how talk about the traumatic experiences of being involved in the Christchurch earthquake is initiated and managed in one early childhood centre through the everyday interactions between the teachers and children . We discuss the educators’ use of supporting educational resources that respect the children’s social competence in attending to their use and the social context to initiate conversations about the earthquake. The resources include Learning Story books , outdoor excursions to broken environments, and play equipment such as traffic cones and hard hats. The usefulness of these resources to initiate conversations that support recovery talk is demonstrated in transcriptions of unfolding talk about aspects of the earthquake event. The chapter includes a reflection by the teachers who were involved in the research. Their discussion reflects on the inclusion of these resources and their usefulness for initiating earthquake talk. Together, this chapter and the subsequent teacher reflection prompt other teachers to include such resources to help support children’s recovery from traumatic experiences .

Context of the Project

On 22 February 2011 at 12.51 p.m., a 6.3 magnitude earthquake with a depth of only 5 km struck Christchurch, New Zealand Aotearoa. It resulted in the deaths of 185 people (NZ Police, 2012). One area of Christchurch that was particularly affected was New Brighton, where many buildings were severely damaged. As the earthquake occurred during the day, many people were at work and young children were at preschool. For the New Brighton Preschool, the earthquake came at the time of day when kai (meal) time had just finished and the youngest nursery children were asleep in their sleep room. When the earthquake struck, the quick-thinking actions of the early childhood teachers were paramount in ensuring the safety of all children present. The teachers gathered the young children who were awake onto the patch of grass in an open space in the preschool back garden so that they were out of reach of possible falling items that may have been loosened by the earthquake. The teachers gathered around the children in a protective circle in this outdoor space. Inside the building a similar protection of children was quickly initiated. Older children were encouraged to go under tables, with teachers following them so that they were on the outside, protecting the children from anything that might have fallen. Once the earthquake subsided, the older children who had been inside under the tables were taken outside to the grassy area so that they were with friends, but the toddler children were trapped inside the nursery. The teachers worked to gain access to the nursery to help the crying toddlers out of the earthquake-damaged room and eventually managed to open the stuck door to free them. Further actions to secure children’s safety and well-being were managed as the teachers organized food, water, blankets and beanbags on the grass for all the children, as anxious parents began to arrive to collect their children. Throughout this traumatic experience , the teachers’ actions demonstrated a provision of care for the children, as they grew increasingly aware of the possibility that some parents may have been severely affected by the earthquake and may possibly not arrive to pick up their child.

In the days and weeks that followed, an official response to managing the earthquake disaster unfolded. One initiative that was found particularly useful for those affected was the ‘3 Rs’ (Respond, Recover and Renew) (Brown, 2012: 88). The ‘Recover’ aspect of this 3-phase response highlighted the importance of talking about experiences in order to allow ‘emotional recovery’ and progress in making sense of events. Particular connections were made to the New Zealand early childhood curriculum Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education [MoE], 1996/2017), where there is an holistic approach to education, and explicit mention of supporting children’s ‘emotional well-being’ (pp. 15, 46 and 50), ‘emotional robustness’ (p. 21) and ‘emotional security’ (p. 22). The curriculum is foregrounded in sociocultural theory where children are perceived as socially competent members of society who have strengths and funds of knowledge that they contribute to society. Te Whāriki is founded on the following aspirations for children:

to grow up as competent and confident learners and communicators, healthy in mind, body, and spirit, secure in their sense of belonging and in the knowledge that they make a valued contribution to society. (MoE, 1996: 9)

The vision of children as active agents in everyday interaction encourages early childhood teachers to value the contributions of infants, toddlers and young children in everyday interactions so that they are supported to be ‘competent, confident learners who ask questions and make discoveries’ (MoE, 1996: 68). In understanding how conversations about the earthquake disaster are initiated in order to begin this process of recovery and renewal; this chapter focuses on how disclosures about the earthquake were initiated in situ with a focus on children’s social competence in this co-construction.

Initiating Interactions

This chapter brings a sociological focus of inquiry to the everyday interactions that occurred between the teachers and the children, and among the children themselves, to show everyday scenes as they dealt with the trauma caused by the earthquake events. Bringing a situated perspective to the activity makes possible a focus on specific events through focusing on how the participants attend to the interactions occurring. In attending to the visible and audible structures of their talk-in-interaction, we show how the participants work at co-producing their social activities. The focus is not on children’s words alone, nor their developmental capabilities, but rather how they engage with others (teachers, children) to make sense of their everyday worlds. This is particularly relevant when their everyday worlds were so disrupted by the extraordinary earthquake events.

Three fundamental assumptions underpin our understandings of social interaction (Heritage, 1984). First, social interaction is structurally organized. By this, we mean that there are stable patterns of talk that are organized in conversations, and we can study talk as social organization as a topic in its own right. For example, turn-taking is a structurally organized feature of talk. Second, the sequence of talk is important. Interactions are dependent upon preceding talk, and that talk forms the basis of what is said next. In other words, conversation is both context-shaped and context-renewing (Heritage, 1984). It is context-shaped because of a speaker’s contribution in an ongoing sequence of talk, and it is context-renewing because the next speaker’s turn is formed from the current speaker’s immediate context. As well as talk, it is also important in face-to-face interactions to know what gestures (e.g. pointing) and other non-verbal actions (e.g. smiling) occur as these become a shared resource for participants. Within this framing, participants assemble possible meanings drawn from the situated context of the social interaction . These turns at talk are jointly produced by the members present and begin in orderly and structured ways (Sacks, 1992).

Elsewhere, we have described how children spontaneously re-enacted and talked about their trauma around the earthquake event through play (Bateman & Danby, 2013; Bateman, Danby, & Howard, 2013b; Bateman, Howard, & Danby, 2015). These experiences, self-initiated by the children, were serendipitous moments where the teachers initiated talk about the earthquake alongside the children’s play activities. The teachers in our study interacted in ways with the children that produced talk that was similar to therapeutic interactions in a clinical setting . For example, therapists may join in with the child’s play to provide opportunities to support the child to understand the event and, consequentially, to reframe the children’s trauma responses (Prendiville, 2014). Other therapeutic strategies include creative arts -based activities such as drama and performance to create an emotional distance from the event to facilitate healing (O’Connor, 2012). Negative exposure therapy supports children to construct narratives of their experiences in order to become children to relive these experiences to become more habituated to those experiences of trauma (Ruf et al., 2010). Institutional helplines such as the Australian Kids Helpline offer a safe and caring environment where they support the young callers to communicate their troubles, and counsellors provide counselling support through promoting self-directed solutions (Danby, Butler, & Emmison, 2011). Although professional counsellors can offer essential healing, an approach involving non-specialist staff such as parents, teachers and friends also has been found to be effective in supporting children through traumatic events to begin the process of recovery and healing (Gibbs, Mutch, O’Connor, & MacDougall, 2013). This chapter now explores the initiation of earthquake talk between children and their teachers.

The Project

The imperative for the project was an exploration of how children and teachers were responding in their everyday interactions with each other in the days that followed the earthquake. The project catalyst was initiated by parents and early childhood teachers requesting knowledge about how to best support their children through recovery (Dean, 2012). The project aim was to reveal what was happening in everyday practices, so that lessons could be learnt regarding how earthquake talk was being managed in situ. To begin the project, ethical approval was gained from the University of Waikato Ethics Committee, followed by the Preschool Centre director, the parents of the children and, finally, the children. All families agreed to full consent for their children, and all children also agreed to take part, resulting in fifty-two child participants. All nine teachers consented to be involved in the study.

The principal investigator (Amanda Bateman) video recorded everyday interactions between children and teachers to see how the participants oriented to the earthquake in their everyday talk . Video recordings of children’s everyday interactions provided unique access to the children’s cultures, to which adults might not otherwise gain. Video footage affords researchers repeated access to the recorded interactions so that the interests of the participants can be viewed and transcribed in fine detail, allowing researchers opportunities to learn from the interactions viewed (Pink, 2013; Sacks, 1984).

A total of eight hours and twenty-one minutes of footage was collected over the duration of one week at the preschool. Video recordings captured moments when the earthquake was talked about and also play that included fixing broken things. These video recorded episodes were transcribed using conversation analysis transcription conventions (Jefferson, 2004) to reveal detailed features of talk, of what was said by whom in the sequence of the interaction, and also how it was said in order to reveal the social organization in interaction. Some context of the study of initiating conversations by making use of conversation analysis is now given.

Conversational openings were explored as a significant part of everyday interaction in the early work of conversation analysis (Sacks, Schegloff, & Jefferson, 1974; Schegloff, 1968). Initiations of such openings work to secure an interaction, as one person’s first pair part (FPP ) occasions a second pair part (SPP) from another person (Sacks et al., 1974). When a person initiates an interaction with someone through a FPP , they often will use a pre-sequence to ensure that they have the attention of the targeted person before progressing to continue with the interaction. Sacks (1992) suggests that a FPP involves the use of a pre-sequence in order to gauge how their utterance will be received. The recipient shows their willingness to contribute to the interaction through their response, which either can be verbally expressed or non-verbally implemented through actions such as gaze bodily alignment and facial expression (Goodwin, M. H., 2006; Goodwin, C., 2017).

The sequence of exchanges in opening an interaction is observable in everyday interactions, making everyday scenes visible. For example, a question goes before an answer, ‘there is plainly, hearably, a first greeting and a greeting return; they’re said differently’ (Sacks, 1992: 521). Questions often are used as a way of securing an interaction with someone and are used especially by children (Sacks, 1992). Sacks (1992) also suggests that, in the opening of an interaction, people may refer to conversational tickets or objects that can be used as an account for why one person initiates contact with another. Conversational tickets are structured so that they orient to the reason why one person is approaching another, such as asking for the time or for directions (Sacks, 1992). This use of objects for initiating interaction has been explored in prior work (Bateman & Church, 2017) where four-year-old children were found to co-construct the order of the playground through orienting to environmental features and any available objects. In this chapter, we show how teachers and children initiate and organize their talk-in-interaction around environmental resources to accomplish shared meanings about events related to the earthquake and the consequences in their everyday lives post-earthquake.

Data and Analysis

Orientation to Environmental Resources for Initiating Earthquake Talk

The importance of being physically present in the earthquake-damaged environment was relevant for prompting discussion and reflection on the earthquake experiences. There were many buildings that had suffered various levels of damage around the preschool location, and these were unavoidable upon entering and exiting the preschool. We now show how the teachers and children oriented to some aspects of the earthquake-damaged environment and not to others.

Direct Initiation of Earthquake Recall

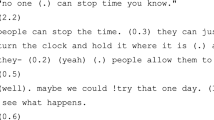

Fragment 1 shows how the teacher uses everyday sand play to prompt talk about liquefaction. The preschool teacher Lorraine (LOR) is sitting next to the sandpit where many of the children are playing . One preschool girl, Maiah (MIA), is sitting on her lap and 3 other girls (Chloe—CLO; Sienna—SNA; and Milika—MKA) are crowded around her. The teacher begins with some questions designed to prompt memories of the earthquake event and to prime the children in terms of thinking about their daily lives following the earthquakes.

Fragment 1

Bateman and Danby (2013)

Counselling guidelines often recommend the strategy of avoiding questions when discussing traumatic events with children, as counsellors are not familiar with the children’s prior experiences (Graffam Walker, 2013). The preschool context shown here, however, is not a formal counselling context. Teachers, because of their daily interactions with children, often do have a substantial knowledge about children’s lives, including knowledge about family members, where they live, and prior experiences as shared by the children and families. This shared knowledge is readily available and becomes a resource for the teacher, as shown in this particular sequence of talk.

This sequence of talk is triggered by the children’s investigations of liquefaction in the sandpit, and the teacher uses this experimentation to initiate a sequence of questions about their memories. She begins by asking children to remember, first, about the sinkhole and, next, about the potholes. While she does not specifically refer to the earthquake, it is clear that the children make the connection to the earthquake in their subsequent talk, demonstrated by Chloe in her explicit mention (lines 16–17). The teacher’s approach both prompts talk about a particular topic—liquefaction—and provides interactional space for the children to initiate explicit references to the earthquake if they chose to do so.

After Chloe produces her first telling prompted by the teacher’s questions, and the teacher initiates a second telling recounting a conversation she had recently (lines 21–24). In introducing this topic, done as a retelling of a conversation with another child, she shapes this in a way so that others, including Sienna, also contribute their recalls to the collective group. When one story leads to another, these stories are described as ‘second stories’ (Sacks, 1992). A second story is designed to show mutual attention towards both the talked about event and associated understanding displays of ‘recognizable similarity’ (Arminen, 2004: 319). Here, we see that the telling offered also follows this systematic format. As well as clearly displaying association with the first telling and a shared experience, the teller identifies with the prior teller and their experiences, and as such reminds children that they are not alone in relation to their experiences of the earthquake. The teacher’s use of questions about the environmental resources works to orient the children to the concept of liquefaction and to link that back to the earthquake event, which produces the context for the production of reflective recalls here. This orientation to environmental resources to prompt earthquake recall is also evident in the subsequent transcriptions and so appears to be a common practice in these teacher–child interactions.

On the Way to the Hole in the Road

Fragment 1 showed how a particular environmental feature was talked into importance by the teacher and children, and how the unfolding talk prompted a connection to the earthquake. The same type of strategy is used in the following interaction shown in Fragment 2.

This event occurred in the morning when children and teachers found that, on entering the early childhood centre, there was no water. After some investigation through talking about the situation with others, the teachers found that the earthquake had caused the tarmac of a nearby road to weaken. The road had given way when a large lorry had driven over it, causing damage to the underlying water pipe. As each experience like this was treated as a learning opportunity by the teachers, the children, Myla (MYL) and Sienna (SNA) and teacher Pauline (PLN) went to investigate the situation. The following sequence shows how the teacher initiates talk about the earthquake through an environmental noticing .

Fragment 2

(Bateman, Danby, & Howard , 2013a)

At the beginning of this sequence, the teacher makes a noticing by drawing attention to the broken wall. She does so without giving additional information about what to ‘look at’ or why, accomplishing this initial noticing with gesture as well as her verbal opening as she looks at the wall. The teacher manages this initial opening by using a pre-sequence (line 1) to ensure that she has secured the attention of the children before progressing further with the interaction and specifically draws their attention to an environmental feature . There are various types of pre-sequences that are used to establish activities in the initiation of a preferred, agreeable interaction (Schegloff, 2007) where they are used as introductions to subsequent talk (Schegloff, 1980). Here, this pre-sequence solicits the attention of the children, while also initiating the progression of the interaction to be around the topic of the broken wall.

Following this first noticing ‘oh look’, there is a two-second silence where there was opportunity for the children to contribute; another common practice, but as there was no immediate response, Pauline continues with ‘what’s that here’. This utterance draws further attention to the broken wall, so that Pauline’s initiation of this sequence consists of a double attention elicit involving the environmental feature in her conversational opener. This time, she uses a question in her FPP to make the response of an answer relevant. In doing so, she sets up a specific topic of talk from the beginning of the interaction in her FPP, prompting a specific type of SPP response from the children that will be obliged to be about the object she has attended to (Sacks, 1992). As with Fragment 1, the orientation to environmental resources is evident here in prompting children to engage in talk about the earthquake .

Pauline’s initiation of this interaction uses a question that prompts the children to reply with a demonstration of their knowledge, acknowledging the children’s competence and giving them the opportunity to contribute. Myla responds with a minimal response token (line 5), which requires Pauline to reformulate her question, again offering the children the opportunity for contribution. In Pauline’s next turn at talk (line 6), she uses ‘I wonder’ to prompt a knowledge display from the recipients (Houen, Danby, Farrell, & Thorpe, 2016a, 2016b). Even though the next couple of lines (7–8) suggest a lack of engagement, another child then does attend to the wall (line 10), prompting Myla to then offer her contribution of knowledge (lines 12–13).

Through progressing with this enquiry as an opening of interaction in this focused way, Pauline acknowledges the children’s competence by providing opportunity for them to offer their hypothesis around what has happened, even if they do not know the ‘correct’ answer. This opportunity is subsequently picked up by Myla who offers a hypothesis for why the wall is broken by orienting to the earthquake, demonstrating her knowledge and understanding of events. Myla’s response to the initiated topic provides opportunity for Pauline to follow Myla’s interest and understanding of events by unpacking further issues surrounding the earthquake. This sequence demonstrates how initiating an interaction through an environmental noticing by using ‘I wonder’ and leaving pauses has sequential opportunities for children to show their competence in talking about their earthquake experiences.

The Hole in the Road

Continuing from the walk-in Fragment 2, the children Myla (MYL), Sienna (SNA), Lucy (LCY), and Cayden (CDN), and teachers Pauline (PLN) and Sandra (SDR) finally reach the hole in the road, where more talk about the earthquake is prompted.

Fragment 3

(Bateman et al., 2013a)

As in Fragment 1, Pauline initiates the interaction by making a noticing about a specific environmental feature , prompting the children to come and look at it, placing emphasis on gaining visual access to see it (lines 71–76). This initial noticing is followed with a significant gap in the talk of over a second while the teacher shepherds the children (Cekaite, 2010) around the hole. This gap in the talk, although used to position children, also affords opportunity for the children to contribute their opinion and/or knowledge about the environmental feature ; a common practice found in the data discussed in this chapter. Ending this gap with her response, Myla also orients to the need to see the environmental feature that Pauline is drawing her attention to, highlighting the need for first-hand knowledge of the scene. First-hand knowledge can be secured through being an eye-witness to an event, as physically observing specific episodes can provide authentic experience through connecting with emotions (Hutchby, 2001). Through providing an opportunity for the children to see the environment in post-earthquake state, the teachers provide legitimate first-hand knowledge for the children in a situation where they can ask questions and offer their knowledge about the event. As such, these experiences afford tools and knowledge to talk about events with children in the process of their recovery (Brown, 2012).

Pauline continues drawing the children’s attention to ‘look’, repeating the word twice and with emphasis, and this time is more specific about which environmental feature to which she is directing their attention—‘that huge hole’—in order to gain understanding. This prompt is followed by a second teacher, Sandra, also asking the children to ‘look’ (line 77). Sandra’s guidance for the children to ‘look’ makes the first specific mention of the earthquake in this interaction, as she tells the children it is the reason for the road being broken (line 77). Pauline takes the opportunity to talk to the children about factual knowledge around the broken road here, and how it is related to the recent earthquake. Towards the end of this interaction (lines 100–105), Pauline prompts Cayden to contribute to this topic by acknowledging that he has knowledge that is worthy of sharing, demonstrating that his contribution is valued, and presenting him as competent in adding to the knowledge that is already being shared. Cayden does contribute, initially through gesture as he nods his head in response to Pauline’s question, and then verbally where he offers news that the hole in his street is deeper than the one they are currently looking at, disclosing details about the impact of the earthquake.

The sequences reveal how an impromptu physical exploration of an environmental feature related to the recent earthquake can provide opportunity for spontaneous earthquake talk. The teacher initiated the topic by orienting to specific environmental features that she encouraged the children to engage with first-hand and offered facts about the earthquake and the damage it caused. As such, this sequence of verbal actions worked to provide an opportunity for the children to contribute their knowledge in competent ways, so to build a clearer understanding of the impact of the earthquake from equally valued various perspectives.

Learning Story Books: Important Documentation for Initiating Reflection

At the beginning of the research project, the children at the early childhood centre were informed that the researcher was interested in hearing their stories about the earthquake, and this introduction was enough to prompt some children to recall events without further prompting. The following three fragments reveal how Learning Story books , used to document children’s learning and prompt reflection on that learning, are an important resource for recording children’s earthquake experiences for later revisiting. The Learning Stories approach is a formative assessment for children attending early childhood education in New Zealand, where episodes of children’s learning are documented for reflection, supporting children to see themselves as capable and confident learners (Carr & Lee, 2012). Teachers document the learning of each child by writing a story to the child about their learning accomplishments, where there is great focus on children’s competence . Each child has their own collection of stories that are produced into books for the children to keep and reflect on throughout their continuous educational journey.

The following two fragments (4 and 5) show how two of the four-year-old children competently initiated an interaction with the researcher using their Learning Story books to tell about their earthquake experiences; Fragment 6 shows a collaborative remembering of the earthquake between a teacher and child using his Learning Story book.

Baxter and His Learning Stories

In Fragment 4, one child, Baxter (BAX), showed the researcher his book and started talking specifically about the earthquake events that he had documented in there. This was an extended turn at talk where the researcher did not say anything. Baxter talks and turns his pages simultaneously, where the pictures and words support his telling about his earthquake experience.

Fragment 4

(Bateman, Danby, & Howard , 2013b, 2016)

Baxter is using one of his Learning Story books to tell stories about his earthquake experience to the researcher who is video recording him. Although the prior fragments demonstrated how a teacher’s orientation to an environmental resource was used to prompt earthquake talk with the children, the prompt for earthquake talk here comes from the documentation in Baxter’s Learning Story book . He competently offers a telling of news about events that he experienced first-hand, as documented in his book through writing and photographs of people, places and things. As with Fragments 1 and 2, his documented first-hand knowledge highlights the importance of being a present eye-witness (Hutchby, 2001). Baxter orients to this first-hand experience when he competently recalls a list of people who were physically present at the time, as he makes his disclosure about events, often using gesture as he points to specific pictures as he talks. In this particular part of the telling (lines 11–12), Baxter uses self-repair from ‘we’ to an actual list of names of the group, and photographs in his Learning Story book to stress the importance of being as accurate as possible when recalling this earthquake story, and so offers further validation of his story (Sacks, 1992). Baxter’s recipient design in his telling can be observed, where he offers specific names of members to which the researcher would not otherwise have access. Baxter’s subsequent orientation to having a ‘first look’ (lines 13–14) also demonstrates the importance placed on being present and being first with the news (Sacks, 1992).

Whereas the prior fragments demonstrated the usefulness of exploring damaged environments for initiating talk about earthquake experiences and offering opportunities for children to contribute their knowledge, here we see that Learning Story books can be equally as important resources for facilitating such talk. The way in which Baxter attends to each page in the process of telling his earthquake stories reveals the vital role that the documented stories and pictures played for such important disclosures when the stories were revisited. When reflecting on the story of the fence (lines 20–26), Baxter switched from past to present changing from ‘that’ (line 23) to ‘this’ (line 24) with emphasis placed on these words, while referring to the fence as a pivotal utterance to link his present situation with his past earthquake one (Bateman et al., 2013b). Learning Story books can be valuable artefacts for prompting and reflecting on earthquake experiences.

The observable way that Baxter used each page and picture to prompt his specific tellings (noted by the page turning) indicates the importance he placed on using Learning Story books to document events that can be returned to in the iterative process of coming to terms with an event (Brown, 2012). By documenting events in Learning Story books , the books provide a valuable resource for initiating talk and reflective thought, as also evident in the next transcription.

Cayden and His Learning Stories

Cayden (CDN) approached the researcher and asked if he could show her his book. The researcher accepted, and Cayden placed his book on the table and opened it on a page about the earthquake. Cayden held the clip-on microphone close to his mouth and began speaking into it while pointing, with his other hand, to the picture in his book.

Fragment 5

As with Fragment 4, Cayden immediately begins talking about the earthquake as documented in his book and using the words and pictures about the earthquake as support. Cayden places emphasis on the earthquake breaking things and creating holes, which becomes significant when we see that in Fragment 2 Pauline asks Cayden about the hole in his road, indicating that Cayden has documented this experience and is now recalling it. The documentation in the Learning Story book, as well as excursions to the broken environment, provides different types of opportunities for initiating earthquake talk for reflecting on past events and coming to terms with events. What is significant here, and in Fragment 4, is the competent ways in which Baxter and Cayden use their books to articulate the earthquake experiences that are of significance to them.

Leonie and Zack Read Zack’s Learning Story Book

In this interaction, the early childhood teacher, Leonie (LEO) and 3 children are sitting on the grass in the preschool outdoor area. Each child is looking at their own Learning Story book, when the book becomes the stimulus for recalling the events around the earthquake. Two children leave and Leonie and Zack (ZAC) remain. The following interaction occurs:

Fragment 6

(Bateman & Danby, 2013)

This interaction around the documented earthquake Learning Story in the Learning Story book has been analysed previously to reveal how remembering the earthquake was a collaborative matter—a process that helped make sense of what happened during a tumultuous event (Bateman & Danby, 2013). Here, we focus on how the topic of the earthquake was initiated through the presence of the Learning Story book resource , affording opportunity for Zack to knowledgeably and competently disclose his memory of the earthquake in a secure environment with his teacher. Here, the teacher uses Zack’s Learning Story book to prompt earthquake talk, and also uses pauses and gaps in talk to afford Zack an opportunity to contribute, both common practices used by the teachers’ interactions, as shown in this chapter.

As with Baxter and Cayden, Zack initiates the reading of his Learning Story book by independently turning the book to the page where the earthquake is documented. Rather than reading the selected story to an audience, however, Zack hands the book to his teacher Leonie and asks her if she can read it (line 1). In doing so, Zack competently communicates to his teacher that he would like the focus of the story sharing to be about the earthquake. Leonie notices the story topic and recognizes the initiation from Zack as an important moment, responding in a way that prompts Zack to recall his earthquake experience (lines 2–5). This sequence of notice, recognize and respond is practised by early childhood teachers in their everyday pedagogy in New Zealand to support and extend children’s learning experiences (Carr & Lee, 2012). Here, the learning experience is centred around recalling the earthquake through the ‘revisiting’ process, affording the opportunity for recovery through the iterative process of recalling experiences in order to come to terms with events (Brown, 2012). Zack then embraces the opportunity to demonstrate his competence in offering a hypothesis about what happened during the earthquake (line 16), further demonstrating the importance of documenting events and revisiting them in Learning Story books.

Discussion and Conclusion

Trauma is profoundly unsettling and distressing, and children who have experienced such events are likely to receive specialist support in the form of counselling or therapy. This process often involves maximizing children’s capacity to disclose and describe the traumatic event , develop new ways to deal with their emotions, and develop new perspectives of the event and of themselves (Bateman et al., 2015).

An investigation of how children and teachers invoke talk about their traumatic experiences requires detailed insights into the systematic ways in which they introduce and discuss their experiences of trauma . In the episodes discussed in this chapter, we see two main common practices that prompt earthquake talk from the children: (1) orientation to environmental resources and (2) pauses and gaps in conversation that afford the child the opportunity to contribute their earthquake experiences . The teachers’ interactions with the children produced conversations that invoked memories of the earthquake for both teachers and children. These accounts often began with an account of a memory of what happened when the earthquake occurred in terms of how they responded to this traumatic event , and the damage sustained to the community. As shown in these examples, these reported memories also became the interactional resources to reshape their accounts of that eventful day and aftermath. These reshaped accounts shifted to more positive discussion of how the community is being repaired, how community members were helping each other, and alternative ways to describe the earthquake that were more playful (e.g. Fragment 6, ‘the dinosaurs were dancing’).

The strategy of recalling experiences of traumatic events is important in children’s lives in the process of the strategy of Respond, Renew and Recover (Brown, 2012). As the analysis highlighted, walks with children and the children’s Learning Stories books support the children’s telling. Further, the teacher’s use of questions was designed to prompt displays of remembering. Engaging with the immediate environment and Learning Story books worked as extra props for the teacher’s work, affording the opportunity for the children to recount their experiences. The teacher’s probing through questions was undertaken in a peer context and, when the children gave their accounts, the reported memory was undertaken within a social context. This multiparty talk was heard by those present, as each built on the other’s account, providing opportunity for accumulative knowledge through collective accounts that build ways to normalize and further understand the experience for the children.

The study has potential limitations in that the participants were aware that the researcher was particularly interested in the earthquake. This aligns with prior conversation analysis work with young children (Ekberg, Danby, Houen, Davidson, & Thorpe, 2017), where it is possible that the researcher’s topic of interest impacted on the frequency of discussion of that specific topic. However, similar to the Ekberg et al. (2017) study, much of the footage collected did not include any discussion of the earthquake, suggesting that the children’s interests were the main focus of everyday discussion rather than the researcher’s primary interests.

Understanding children’s spontaneous talk with their peers and teachers about their earthquake experiences , and the teachers’ role towards supporting children’s emotional recovery, recognizes the value of non-specialist involvement in children’s everyday activities. Children’s ‘crisis’ talk or disclosure of traumatic events , when initiated or supported by non-specialists such as teachers, has similarities and differences to how specialist therapists support children (Bateman et al., 2015). There are similarities in that specialists and non-specialists can prompt storytelling about an event, but there are also differences in that teachers and children can display connections through collaborative sharing of events that both have experienced. Further, teachers were more often present and could wait until the moment children spontaneously initiated topics of concern.

Through providing opportunities for children to contribute their voice in everyday interactions, their social competence in managing the recovery process through producing ‘tellable’ accounts (Bateman et al., 2013a, b) and their role in the co-production of making sense of the disaster through storytelling (Bateman & Danby, 2013) becomes evident.

References

Arminen, I. (2004). Second stories: The salience of interpersonal communication for mutual help in alcoholics anonymous. Journal of Pragmatics, 36, 319–347.

Bateman, A., & Church, A. (2017). Children’s use of objects in an early years playground. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 25(1), 55–71.

Bateman, A., & Danby, S. (2013). Recovering from the earthquake: Early childhood teachers and children collaboratively telling stories about their experiences. Disaster Management and Prevention Journal, 22(5), 467–479.

Bateman, A., Danby, S., & Howard, J. (2013a). Everyday preschool talk about Christchurch earthquakes. Australian Journal of Communication, 40(1), 103–123.

Bateman, A., Danby, S., & Howard, J. (2013b). Living in a broken world: How young children’s well-being is supported through playing out their earthquake experiences. International Journal of Play, 2(3), 202–219.

Bateman, A., Danby, S., & Howard, J. (2015). Using conversation analysis for understanding children’s talk about traumatic events. In M. O’Reilly & J. Lester (Eds.), Handbook of child mental health: Discourse and conversation studies (pp. 402–421). London: Palgrave.

Bateman, A., Danby, S., & Howard, J. (2016). Living in a broken world: How young children’s well-being is supported through playing out their earthquake experiences. In C. D. Clark (Ed.), Play and well being (pp. 202–219). Oxon: Routledge.

Brown, R. (2012). Principles guiding practice and responses to recent community disasters in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 40(4), 86–89.

Carr, M., & Lee, W. (2012). Learning stories: Constructing learner identities in early education. London: Sage.

Cekaite, A. (2010). Shepherding the child: Embodied directive sequences in parent-child interactions. Text & Talk, 30(1), 1–25.

Danby, S., Butler, C. W., & Emmison, M. (2011). ‘Have you talked with a teacher yet?’: How helpline counsellors support young callers being bullied at school. Children and Society, 25(4), 328–339.

Dean, S. (2012). Long term support in schools and early childhood services after February 2011. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 40(4), 95–97.

Ekberg, S., Danby, S., Houen, S., Davidson, C., & Thorpe, K. J. (2017). Soliciting and pursuing suggestions: Practices for contemporaneously managing student-centred and curriculum–focused activities. Linguistics and Education, 42, 65–73.

Gibbs, L., Mutch, C., O’Connor, P., & MacDougall, C. (2013). Research with, by, for and about children: Lessons from disaster contexts. Global Studies of Childhood, 3(2), 129–141.

Goodwin, C. (2017). Co-operative action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goodwin, M. H. (2006). The hidden life of girls: Games of stance, status and exclusion. London: Wiley.

Graffam Walker, A. (2013). Handbook on questioning children: A linguistic perspective. Washington, DC: American Bar Association.

Heritage, J. (1984). Garfinkel and ethnomethodology. Oxford: Polity Press.

Houen, S., Danby, S., Farrell, A., & Thorpe, K. (2016a). Creating spaces for children’s agency: ‘I wonder …’ formulations in teacher-child interactions. International Journal of Early Childhood, 48(3), 259–276.

Houen, S., Danby, S., Farrell, A., & Thorpe, K. (2016b). ‘I wonder what you know …’: Teachers designing requests for factual information. Teaching and Teacher Education, 59, 68–78.

Hutchby, I. (2001). ‘Witnessing’: The use of first-hand knowledge in legitimating lay opinions on talk radio. Discourse Studies, 3(4), 481–497.

Jefferson, G. (2004). Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In G. H. Lerner (Ed.), Conversation analysis: Studies from the first generation (pp. 13–23). Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Ministry of Education. (1996/2017). Te Whāriki. He Whāriki Mātauranga mō ngā Mokopuna o Aotearoa. Early childhood curriculum. Wellington, New Zealand: Learning Media.

National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE). (2005). Post-traumatic stress disorder: The management of PTSD in adults and children in primary and secondary care. National Institute for Clinical Excellence, London: BPS Publications.

New Zealand Police. (2012). http://www.police.govt.nz/list-deceased.

O’Connor, P. (2012). Applied theatre: Aesthetic pedagogies in a crumbling world. London: Routledge.

Pink, S. (2013). Doing visual ethnography. London: Sage.

Prendiville, E. (2014). Abreaction. In C. Schaefer & A. Drewes (Eds.), The therapeutic powers of play: 20 core agents of change. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Ruf, M., Schauer, M., Neuner, F., Catani, C., Schauer, E., & Elbert, T. (2010). Narrative exposure therapy for 7- to 16-year-olds: A randomised controlled trial with traumatized refugee children. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 24(3), 437–445.

Sacks, H. (1984). On doing “being ordinary”. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: studies in conversation analysis (pp. 413–440). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press and Editions de la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme.

Sacks, H. (1992). Lectures on conversation (G. Jefferson, Trans. Vols. I & II). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking in conversation. Language, 50(4), 696–735.

Schegloff, E. A. (1968). Sequencing in conversational openings. American Anthropologist [New Series], 70(6), 1075–1095.

Schegloff, E. A. (1980). Preliminaries to preliminaries “Can I ask you a question.” Sociological Enquiry, 50 (3–4), 104–152.

Schegloff, E. A. (2007). Sequence organisation in interaction: A primer in conversational analysis (Vol. 1). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Professional Reflection

Professional Reflection

By Paula Robinson and Claire Lethaby

New Brighton Preschool, Christchurch, NZ

Our Story

We want to share with you our story, that is, the story of New Brighton Community Preschool and Nursery, an early childhood centre situated in the eastern suburbs of Christchurch. To share our story we need to set the scene, to tell you a little about who we are and what we experienced but then focus on what we are fairly proud of, that being some of the positive new learning and learning pathways.

The Impact of the Earthquake on the Teachers, Whānau and Children

New Brighton Community Preschool and Nursery was established in 1979 in our eastern, seaside community. We are a not for profit early childhood centre which has always worked proactively for both our children and whānau with whom we proudly work alongside. We experienced four significant earthquakes which also caused closure for varying time periods, added to this were two potential tsunami warnings, a three week period of our road being closed due to potential flooding (luckily for us that stopped two houses away) and the final closure time resulting after two heavy snowfalls! Over this period, our families have had to contend with 41 days of emergency closures, none of which we ever envisaged. At this time, we had 68 families that attended our centre, with children aged from five months through to five years old. Each individual child has undertaken this journey in their own unique style; however, our intention is to portray the main practices which have emerged over this time.

The September 2010 earthquake occurred while we were all home in our beds. While it was a huge experience, it really did not impact on us as directly as subsequent earthquakes. The centre was closed for a couple of days while it was structurally checked, all that occurred was a broom fell over. It did bring a huge awareness to our team and we ensured that practices and procedures in relation to earthquakes were robust. We also ensured that we had appropriate survival kits, even though many of us believed at the time this was a once in a lifetime experience. The children appeared to view the centre as a ‘safe place’ and maybe this was due to the earthquake occurring outside centre hours. Conversations and practices around the earthquake emerged during children’s play, particularly around the shaking feeling, the noise and how it made their bodies feel.

At our teachers’ only day at the beginning of 2011, our team went through our environment looking at the safest places for protection in an ‘event’ and also looking to eliminate any potential hazards. We felt it worthwhile to undertake this exercise together as we had two new teachers and wanted the whole team to hold the same knowledge and information.

It was only two weeks later that the February earthquake occurred. This one was serious, and we evacuated the building to our safest place, which was a lawn area in the back of the preschool playground. Our designated ‘assembly point’ which we used when practising drills had a power line dangling across it, so immediately we had to alter our plans. Initially there were a lot of children who needed cuddles, but in a short period of time a sing-a-long had begun which gave it a picnic type atmosphere. This went on for over an hour while parents were arriving to collect their treasures. Throughout this time, the ground kept rumbling and shaking and our biggest focus was that the children were ok and that the parents, as they arrived, got the support they needed. Many parents had to abandon their cars on roads that were not driveable and make their way on foot, waddling through liquefaction and flooding, sometimes up to their waist. The one thing we will never forget was the look of relief when they saw their child sitting safely in a teacher’s arms. To this day, it still it brings a lump to the throat whenever we think back to it. We stayed on our little grass patch for just over three hours until the last parent arrived.

Initiating Talk About the Earthquakes with the Children

The immediate effects of this quake were the loss of essential services, namely water, power, sewerage and phone. The roads within our community were barely driveable and all shops were closed. This was a change that was forced upon everyone, you had no choice. While some left the area (permanently, or just to escape for a bit), many stayed and tried to get on with adjusting to the new ‘normal’. The word which became part of every child’s vocabulary was liquefaction. Everyone was in survival mode and really went back to the basics. Children learnt that through crazy hard times, they could continue to live and play, just in a less expectant way. This is something that is a valuable attribute, one which many people in life never learn, but these children have, and they will carry with them this knowledge and know-how for life.

Following the February quake, the Centre Manager attended a Ministry of Education workshop focused on Traumatic Events . A key insight from this workshop was to acknowledge what children were sharing from their perspectives and how it felt, but when ending the conversation trying to incorporate what were the good things that happened at and after this time? (‘I was feeling really scared but I got to have a snuggle in bed with mummy’.) This concept guided our belief about acknowledging the difficulty/hardship/challenge/uncertainty/fear, but in our environment, we could also acknowledge the positives, which were and are unique to this situation. We were very aware to hold these conversations with children, this situation was real and affecting their lives, if we talked about with them, maybe it could support them to make sense, meaning or understanding and alleviate some fears.

From this belief, we built a philosophy which was to ‘keep it positive’ for children. Subsequently, before we came back in March 2011 after the five-week February closure, we had already reflected and discussed at length the ways in which teachers could support our children. Having this foundation knowledge and shared understanding set the scene for making the most of those teachable moments and supporting children in making sense of what was happening in our community.

Importance of Going Out into the Environment

We came back to a new ‘normal’. Instead of toilets, we had port-a-loos outside in the entrance foyer, all taps had the heads removed and we used no running water (due to the water still being unsafe to drink). Children had to come with drink bottles of boiled water and hand washing consisted of sanitizer, wipes and more sanitizer. This all seemed like a big ask, but every child and family turned up on our re-opening day. Everyone was desperate to get back to their normal routines and the children appeared keen to get back to their friends and play. Immediately we noticed a change in children’s play. We now had experts in road works, drain layers, GNS scientists, builders and port-a-loo cleaners, just to name a few. The immediate environment was offering a rich curriculum of experiences and knowledge. There was a new-found respect and awareness for people in ‘day-glow’ jackets, particularly the men and women who worked tirelessly outside our houses and always made time to explain what they were doing.

A new learning pathway had emerged over this time and this was an awareness of our ever-changing environment. Around us were continuous roadworks and work on water and sewerage pipes. This was such a rich experience right at our doorsteps and was far too valuable an opportunity to pass up. We made a conscious decision to take the children out to see what was happening in our neighbourhood. Nearly daily we would set off down the road to see the latest happening. We walked with the children and made the effort to point out specific parts of the environment that were damaged and talked to the children about it, asking questions that we hoped would prompt their thinking and understanding. The children were soon creating their own working theories on why something needed replacing or how. The physical environment also created new challenges and that was the flooding that occurred at the end of our street. Our street backs onto the river and with high tides and high water levels, flooding would regularly occur. This again became a site of investigation and the children would note where the flooding was, by taking photos of the mailbox where it was up to, and then come back to the centre to document it all.

Documenting the Earthquake in Learning Stories

These observations and photos were documented in wall displays, which were in the children’s play space at their level. Each day the new photo was added to the display as well as children’s voices about what they had just observed. This became a great site for children revisiting what they had previously noticed and whether it was similar or different to what they had observed that day. It became a record of what was changing around us and we felt empowered; we weren’t sitting back waiting for things to happen to us we were actively noticing what was happening and creating new working theories. Teachers were also busy documenting individual children’s ideas and perspectives in their learning stories. At the time, learning stories were either group stories, which shared these experiences and events, or individual stories, which were focused on individual children’s perspectives . These stories within their learning journey books were a valuable tool for children to revisit with their peers, teachers and whānau both in the centre and at home.

The main focus within these learning stories was acknowledging and celebrating the competence that the children demonstrated at this challenging time. Having photo displays throughout our learning environment of our community and its ever-changing appearance, as well as many learning stories based on key topics around these experiences, meant the conversations were very rich within the environment and often child initiated. Most children were coming in daily, ready to share their own home experiences with their friends and teachers, bringing new knowledge, comparing stories and experiences, then practising and trialling these in their play. We intentionally provided resources, such as florescent vests, hard hats, road cones and clipboards, to support the theme of their play. Teachers were very mindful to follow children’s leads in these conversations. At times conversations served to consolidate learning and ideas. However, teachers were also very mindful to be respectful and sensitive as children had their own experiences of these events.

The June earthquake again occurred while we were at the centre. The first was strong enough to make us evacuate outside and parents again started to come and collect their children. When the second occurred, which was a lot stronger, we only had three children left and a few teachers. The children were soon gone and it was saddening to drive home seeing the broken roads and the liquefaction again. The centre re-opened a week later and we once again welcomed back the children and families. Much of the initial conversations and play was about the earthquakes and the effects these had on each individual’s situation. The children talked like experts about their houses and land, what worked and what didn’t work and the appearance of any new cracks in buildings. They also began to identify the symbols that had now become part of their community. Examples of these include the Red/Yellow/Green stickers and the many different roadwork signs within the area. The children really identified with these signs knowing what each meant and the actions required; again valuable learning sites within our local environment.

In Conclusion

The word resilience is synonymous with Christchurch and one that we like to try to find other words for. This is our unique story, why use such a common word? However, resilience must be acknowledged. You cannot go through so much repetition of challenge and remain unaffected. We don’t believe in the theory that children will just bounce back on their own. We believe that if a child has experienced repeated challenges, yet throughout these challenges their voices are heard, acknowledged and supported, resilience can develop. To gain this disposition, children also need supportive learning partners: peers, parents, neighbours, significant adults and whānau members, not to mention teachers.

We are not wearing ‘rose-tinted’ glasses when writing this. We acknowledge that this story comes from an early childhood ‘centre’ perspective. We also recognize that, as teachers, we were not and are not there at all critical times, such as when a child may not want to go to bed at night or may not want to use the toilet because they are scared. This is our ‘centre’ story and focuses on the positive learning, which we as a teaching team have recognized, acknowledged and focused upon.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bateman, A., Danby, S.J. (2019). Initiating Earthquake Talk with Young Children: Children’s Social Competence and the Use of Resources. In: Lamerichs, J., Danby, S.J., Bateman, A., Ekberg, S. (eds) Children and Mental Health Talk. The Language of Mental Health. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28426-8_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28426-8_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-28425-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-28426-8

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)