Abstract

Children and adolescents in residential-care facilities often have lower academic achievements that their counterparts who are raised at home. Traditionally, residential programs do not prioritize academic achievements, especially at the high-school level, a situation detrimental to their chances to enter institutes of higher education. The Israel Ministry of Education decided to implement a policy change to affect the overall ecology of youth villages (Israeli residential schools), aimed at emphasizing highschool academic achievements as a key to future success. This attitudinal change led to the development of after-school study centers or evening classes within the village, applying non-formal teaching and learning methods in a relaxed atmosphere. Additionally, various support systems were developed in youth villages, all geared toward helping adolescents excel in meeting the challenges of high school.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Israel has a large network of residential facilities with a variety of educational programs, due to special cultural and historical elements. Jewish tradition has a favorable view of leaving home at adolescence for study purposes. This combines with historical and sociological processes related to the nation-building phase that Israeli society is still undergoing. As part of nation building, youth villages were developed – a large network of residential schools for heterogeneous and multicultural youth populations. Children, together with their families, can decide (for many reasons like migration, family difficulties, or school failure) to join these residential settings – living together with peers, with full financial support of the public authorities. Although this residential education model has been functioning for many years, public criticism has been growing of the relatively poor academic achievements of youth village graduates. Children and adolescents placed in residential care facilities have weaker academic achievements than similar populations of young people raised at home (Cashmore & Paxman, 2006; Courtney, Dworsky, Lee & Rapp, 2010; Stein, 2006), perhaps because in caring for vulnerable populations placed in out-of-home care, the priority is stabilizing and caring for emotional difficulties identified. Such prioritizing meant that academic accomplishment was generally considered a minor priority. In Israel, too, where the focus has been on strengthening young people’s emotional wellbeing and helping them develop socially, artistically, and athletically, insufficient attention was given academic success. Although high-school curricula are part of residential programs in Israel, this lack of attention undermined these adolescents’ opportunity for higher education (Casas & Montserrat, 2010; Jackson & Cameron, 2010). Benbenishty, Zeira, and Arzav (2015) who studied this issue in Israel claimed that overcoming the challenge for care leavers to successfully enter and complete higher education could be crucial to breaking the vicious circle of marginality.

The discrepancy in academic achievements between residential-care graduates and their peers who live at home is at the core of the criticism of residential programs in Israel. Criticism intensified in the 1990s, when large numbers of immigrants from Ethiopia and the CIS were placed in low-level vocational learning tracks in residential schools (Lifshitz & Katz, 2015).

Uneasiness increased when the low matriculation achievements of youth village graduates came to public attention (Benbenishty, Zeira & Arzav, 2015; Zeira, 2009), as high matriculation scores are the key to higher education and to prestigious opportunities in the military service and later in the job market. In response, the Ministry of Education, which finances and supervises most of these residential programs, decided on a policy change, beginning by publicizing matriculation scores. In their defense, the directors claimed that their students came from a lower starting point and should not be compared to students in established urban schools. These claims were countered by the argument that these young people entered residential schools with the hope of being enhanced by the round-the-clock educational services offered in these schools.

In addition to the youth villages, there is a second network of residential facilities run by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Social Services (Attar-Schwartz, Ben-Arieh, & Khoury-Kassabri, 2010). These are therapeutic residential-care programs where children are usually being placed by the court or welfare authorities, and research indicated that academic results in these residential facilities were even more problematic and lower than in the youth villages (Zeira & Benbenishty, 2011). These findings increased public criticism of all out-of-home facilities, with the public urging decision makers to work to improve this situation.

2 Israeli Residential Education and Care System

Israel is a relatively young society, where residential schools and youth villages are considered powerful social instruments for educating young people from different ethnic groups, preparing them for a relatively smooth cultural and social post-care transition. A century of upheaval was the impetus for extensive need for out-of-home care for children and young people, beginning with using it as a solution for the many orphan survivors of the World War II Holocaust. These children and young people arrived in Israel and were placed in youth villages or group care in kibbutz communities. Later, these out-of-home facilities were used to assist in the integration of immigrant young people who came to Israel without their parents, especially those from North African countries (Kashti, 2000). These social and historical challenges provided the basis for the large and rather unique network of youth villages, all open settings largely supported by the Ministry of Education. As in other schools, children can leave the youth village whenever they – together with their families – decide that they should leave (Grupper, 2013). This community model is at the origin of many residential education and care programs in Israel. The term “institution” was replaced by the term “youth village,” the change representing more than a semantic difference: The village is an attempt to function as a normative community in which children and adults live together and young people have a sense of belonging. The unique feature of this model is that a normative high school is an integral part of the program.

Some theoretical features of the youth village model developed by the first author (Grupper, 2013) include:

-

Youth and adults living together to create a united community:

-

Creating an atmosphere of residential community living together that avoids the negative effects of an “institution” in Goffman’s (1961) terms

-

Round-the-clock life in a well-designed environment is a very powerful stimulation for achieving behavioral changes among children and young people

-

Relationships between youths and adults are symmetrical (as distinct from the “medical model” or therapeutic orientation and

-

The community is based on pluralistic and multi-cultural values.

-

-

Primacy of education over treatment:

-

Success in schooling achievements is a primary target

-

School is a normative central feature of the residential program

-

Diverse support practices are used to help children experience study successes and

-

Educational considerations override therapeutic ones in making everyday decision.

-

-

Normalization and empowerment of children and staff:

-

Every activity is geared toward challenging the young person to experience success in any kind of activity of his or her choice (e.g. sports, arts, postsecondary studies, assuming leadership responsibilities in the daily routines of the community)

-

Creating a heterogeneous and multi-cultural youth society in the youth village, turning cultural diversity into an asset rather than a burden

-

Eliminating negative stigma by stimulating positive public opinion toward members of the youth community through active involvement of youths in voluntary activities in their neighboring community, such as helping elderly people, coaching young children, performing in ceremonies and festivities of the larger community

-

Self-governance of daily life activities and

-

Empowering young people requires their active enrollment in leadership activities through which they experience taking responsibility and experiencing the rewarding feeling of having successfully accomplished particular social activities.

-

-

Developing children’s sense of belonging:

-

Developing staff commitment to the mission statement: “No child left behind”

-

Creating an atmosphere where every individual has an important place in the youth community

-

Inducing norms of collaboration and mutual support between community’s members

-

Giving adolescents opportunities to act in an atmosphere that enables a genuine “Moratorium” or “Time-Out” and

-

Making all efforts to re-connect youths with their parents and to their society.

-

2.1 Types of Residential Care Programs

According to the Schmid Report (2006), Israeli authorities recognize six different types of residential programs, each with its own level of funding (listed here from lowest to highest):

-

(a)

Residential education and care programs (residential schools or youth villages)

-

(b)

Rehabilitation residential-care programs

-

(c)

Therapeutic residential-care programs

-

(d)

Post-psychiatric residential-care programs (replacing hospitalization)

-

(e)

Residential crisis intervention shelters

-

(f)

Residential programs for delinquent youth (under the responsibility of the Youth Protection Authority)

The first type, often associated with the idea of “living at school” (Arieli, Kashti, & Shlaski, 1983), hosts 85% of children and young people being educated in Israel in out-of-home care programs. It represents a large variety of programs, all of which are supervised and financed by the Ministry of Education. The remaining five types are financed and supervised by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Social Services. Unlike the youth villages and residential schools, enrollment is not voluntary – the children and adolescents are usually referred by courts or are placed there by the welfare authorities.

Israel, like many other Western countries (Islam & Fulcher, 2016), has experienced a decrease in residential education and care, from 14% of the 12–18 year-old population in 1990 to 10% in 2008 and 9% in 2015. Nonetheless, the residential school/youth village system is still in use, with enrollment of young people aged 12–18 from a wide range of cultural and social backgrounds, particularly to empower immigrant youth. In Israel, about 15% of students aged 3–18 years are not native Israelis, and over 14% of those in the 12–18 age group are educated in a variety of residential schools of the youth village type (Ben-Arieh, Kosher, & Cohen, 2009).

Underlying the conceptual framework of the Israeli residential education and care network is the perception that all the different programs are located on a single continuum, and this perception is shared by practitioners and policy makers as well as by children and parents. With this vision of private, “elite” boarding schools at one end of the continuum and residential crisis-intervention centers at the other, all other models are located in-between. This means that children placed in a residential treatment center know that they have the option to move after a while, having made sufficient progress, to a more educational type youth village and vice-versa.

3 Toward Improved Academic Achievements: The Ecological Model for Policy Change

Policy changes take place through “top-down” policy decisions or “down-up” processes. The educational policy change for residential schools was initiated by leaders of the Ministry of Education and implemented from the top down to the residential education network as a whole. The Ministry of Education was forced to act following the widespread large public campaign led by NGOs lobbying for better integration of the Ethiopian community. Researchers and other social activists joined and demanded to raise public awareness of the low academic results in residential education programs.

The influence of Israeli youth villages on children can be explained using Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) Ecological Theory. Here, children’s development is not influenced merely by their daily interactions with the micro -level system but is also significantly impacted by the meso system (interaction of microsystems, such as family and school) and exo systems. Although young people may not be engaged directly with the exo system, they could be impacted by changes occurring at that level (e.g., changes in a parent’s workplace), and even more for interventions emanating from the macro level – overarching institutions and socio-political processes (e.g. government bureaucracies). Israeli residential education and care settings are organized in a relatively large network which affords them a large measure of autonomy, yet they must adhere to nationwide educational and care directives, which can serve to introduce policy changes, whenever they are needed.

It was clear that a major policy change would have to begin by changing the attitudes of directors and staff, emphasizing the new priority to be given to academic achievement. As stated before, recent studies by Zeira & Benbenishty (2011), Benbenishty, Zeira & Arzav (2015) have clearly shown that despite the large amount of resources and money invested by Ministry of Education in these educational programs, the educational gap between them and non-residential high schools was still large, and young people in care were not matriculating. Therefore, researchers, scholars, media people, social activists, all acting on the macro level, have influenced public opinion and steered decision-makers to adopt a new priority. Program designers, staff training programs, supervisors, and program directors, all acting within the meso and exo systems were called upon to initiate and conceive concrete programs.

The outcome was a new Ministry of Education policy in 2012. The Ministry decided to allocate major financial resources to youth villages, with the expectation of significant improvements in the achievements of youth village students. A special unit of four supervisors was established, entrusted with developing and initiating new programs geared at improving academic achievements of youth village students. One of their major initiatives was the development of “study centers” or “evening classes” and other innovative programs, like intensive “marathons” before crucial exams, personal tutoring and smaller classes, all applying non-formal methods in a relaxed atmosphere. These new evening programs, led by direct-care staff and the school teachers, completely changed the micro-level learning atmosphere. According to Milo-Aloni (2019), in 2016 such study centers were operating in 43 youth villages, and by 2019 in 70 youth villages. Schools in youth villages are required to submit monthly reports of their concrete activities to improve academic standards.

Supervisors of the Ministry of Education are on hand to constantly follow up these new programs and scrutinize the matriculation results for each youth village. Finally, yet importantly, large sums were allocated to youth villages by the Ministry of Education (more than 8 million US dollars a year), to develop and operate these new learning centers and related initiatives (Milo-Aloni, 2019).

These combined activities have succeeded in creating a completely different “ecological environment” for children in residential education and care facilities, which has created real change in young people’s scholastic achievements. In 2016, Efshar (literally – It Can Be Done), the Israeli professional journal for social educators, dedicated an issue (# 27) to discussions of all aspects of these efforts. The issue, Studies, education and diploma: The key for changing the situation of children and youth at risk (Gilat, 2016), listed a great variety of programs and initiatives developed in youth villages and residential care programs and second-chance programs for youth at risk. The special issue included an article about informal evening learning centers in youth villages, another on methods for increasing motivation for learning among youth at risk in residential-care settings and one on learning programs in residential programs for delinquent youth (run by the Youth Protection Authority) – Education as essential resource for success in life.

4 Primary Empirical Data

This policy change is relatively new, and has yet to be sufficiently documented, researched, and formally assessed. However, as stated before, passing the matriculation test is a prerequisite for higher education, and most of the criticism of out-of-home care facilities was based on the poor results of residential-education graduates and care graduates on these tests. One of the tools used by leaders of the residential education department in the Ministry of Education was to engage the supervisors as change agents, asking them to broaden their focus from quality of life and social and rehabilitation programs and give priority to learning processes. They were also advised to follow up the academic success rates of youth village students, particularly their matriculation scores.

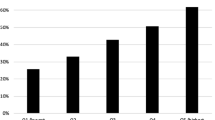

Systematic follow up of residential school graduate’s success rate in National Matriculation tests show a net positive effect. Starting with 36% of success in 2013 (compared to 66.9% national average), it moved to 46% in 2014 (in comparison to 66.17% national average), 54% in 2015 (compared to 66.13% national average), 57% in 2016 (compared to 64.20% national average), 63% in 2017 (compared to 61.80% national average) up to 70.00% in 2018 (compared to 64.10% national average) (Fig. 13.1).

As these figures demonstrate (Milo-Aloni, 2019), the policy change has improved the academic achievements of youth in care year-on-year between 2013 and 2019. Moreover, the gap between the success rates of youth in care and the national average figures has narrowed in that time. Measuring one variable only (matriculation scores) could be problematic methodologically, as such an increase could be the result of cumulative efforts, among them developing special courses for improving learning competences, reducing the number of students in a class, and personal mentoring. However, the upward trend of these figures is very clear and is clearly indicative of the overall success of this policy change.

5 Discussion

In most industrialized countries, residential education and care as a rehabilitation vehicle for children and youths at risk is declining (Del Valle, Sainero & Bravo, 2014; Knorth &Van de Ploeg, 1994; Trede, 2008; Whittaker, Holmes, Del Valle et al., 2016), primarily because of the negative stigma attached to any kind of institutionalized setting. Such settings are viewed as a last resort in many Western countries, a solution to be applied only when all other interventions have failed (Frensch & Cameron, 2002).

In addition, the ever-increasing cost of treating a child in a residential-care therapeutic program is encouraging policy-makers to look for less expensive solutions, even though the effectiveness of these alternatives can often be doubtful (Grupper, 2003; Eurochild, 2010; Everychild, 2011; Knorth, Harder, Zandberg & Kendrick, 2008). Almost every model of residential care appears to have lost popularity in the industrialized world. Emotional rehabilitation in residential care is often considered too expensive and not in line with the actual trend of deinstitutionalization and preference for family-type placement. The 2014 “Consensus paper” (American Orthopsychiatric Association, 2014), which stated that no groupcare program can enable children to develop efficient attachment (American Orthopsychiatric Association, 2014), began a wide polemic among researchers who challenged this statement. Whittaker et al. (2016) published a new statement elaborating the benefits of quality therapeutic residential-care programs and their ability to develop attachment among children in care. However, it should be noted that elite populations and even upper middle-class families are demonstrating less interest in placing their adolescents in boarding schools, or residential schools as the daily reality of these programs is not compatible with the general contemporary ethos of “individualism”. Consequently, even the most prestigious public schools in Great Britain are having difficulties recruiting candidates; some schools have been closed, others transformed into boarding schools for upper middle-class adolescents with social and emotional problems (Duffel, 2014).

Residential education and care networks in Israel were, and still are, a very important social instrument for coping with complex educational and social challenges. Such programs have proven themselves highly instrumental in obtaining successful social integration of immigrant youth in Israel, especially unaccompanied minors, which is a somewhat atypical “migrant society” (Eisikovits & Beck, 1990; Grupper, 2013). Although unaccompanied minors are often associated with refugee populations, in Israel, this phenomenon is also prevalent among Jewish young people who come to Israel from different countries without their parents. Life with Israeli peers in youth villages enables them to decide if they wish to stay and become Israeli citizens. It has also proven to be an important asset in re-integrating disconnected youth in a variety of at-risk situations.

Community life, involving shared living of young people and their educators, creates vast opportunities for developing a sense of “belonging”, first to the small peer group, later to the youth community. Hopefully it will lead to the development of adults with a sense of belonging who will be positively connected to their family, community, and society. Such educational challenges cannot be achieved by residential institutions characterized as a closed “total Institution” or “Goffmanian Asylum” (Barnes, 1991).

Residential programs are bound to modify themselves according to social changes occurring in the environment in which they operate. This is true everywhere, including Israel. The main changes occurring in the Israeli residential network in recent years are focused in four areas:

-

Involving parents in children’s lives while in care (Grupper, 2008)

-

New and better collaboration with surrounding communities (Kashti, 2000)

-

Developing different kinds of programs for supporting care leavers (Benbenishty & Zeira, 2008) and

-

Higher prioritizing of academic achievements (Milo-Aloni, 2019).

In this paper we focused on the fourth area. We elaborated about the vast efforts made in the youth villages to change the ecology of the programs, to guarantee that youth in care receive optimal opportunities to achieve success in their high-school studies, as a key element in opening future opportunities for them as adults. Early indications presented here are encouraging, although we believe that further research and application of additional evaluation tools are necessary.

6 Hopes and Fears

Looking toward the future, we hope that the powerful social instrument that was so efficient until now for coping with complex social challenges will be allocated public legitimacy and adequate resources. Such allocations will help work toward empowering new generations of young people who wish to join residential programs and are able to take advantage of such opportunities. However, this implies that residential programs no longer be considered the “last resort” for vulnerable young people. On the contrary, these programs could be considered the preferred option for those young people who feel that they can benefit from such a learning and living situation. Those young people may be ready to experience the challenges of out of home care programs to benefit from their empowerment and healing potential. This will be accepted by decision-makers only if these programs help young people in care to improve their academic achievements, which, in turn, will open new opportunities for successful transition into mainstream society.

References

American Orthopsychiatric Association. (2014). Consensus Statement concerning the impact of out-of-home group care settings on children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(3), 219–225.

Arieli, M., Kashti, Y., & Shlasky, S. (1983). Living at school: Israeli residential schools as people-processing organizations. Tel Aviv, Israel: Ramot.

Attar-Schwartz, S., Ben-Arieh, A., & Khoury-Kassabri, M. (2010). The geography of children’s welfare in Israel: The role of nationality, religion, socio-economic factors and social worker availability. British Journal of Social Work, 4(6), 1122–1139.

Barnes, H. B. (1991). From warehouse to greenhouse: Play, work and the routines of daily living in groups as the core of the milieu treatment. In J. Beker & Z. Eisikovits (Eds.), Knowledge utilization in residential child and youth care practice (pp. 123–157). Washington, DC: Child Welfare League of America.

Ben-Arieh, A., Kosher, H., & Cohen, S. (2009). Immigrant children in Israel 2009. Jerusalem: National Agency for Children’s Wellbeing (Hebrew).

Benbenishty, R., & Zeira, A. (2008). Assessment of life skills and the needs of adolescents on the verge of leaving care. Mifgash (Encounter: Journal of social-educational work) (Vol. 28, pp. 17–45). Hebrew.

Benbenishty, R., Zeira, A., & Arzav, S. (2015). Educational achievements of alumni of educational residential facilities. MIFGASH(Encounter: Journal of socialeducational work), 23(42), 9–35. (Hebrew).

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Casas, F., & Montserrat, C. B. (2010). Young people from a public care background: Establishing a baseline of attainment and progression beyond compulsory schooling in five EU countries. In S. Jackson & C. Cameron (Eds.), Young people in public care pathways to Education in Europe. http://tcru.ioe.ac.uk/yippee. Accessed 17 June 2012

Cashmore, J., & Paxman, M. (2006). Wards leaving care: Follow up five years later. Children Australia, 31(3), 18–25.

Courtney, M. E., Dworsky, A., Lee, J. S., & Rapp, M. (2010). Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at ages 23 and 24. Chicago: Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago.

Del Valle, J. F., Sainero, A., & Bravo, A. (2014). Needs and characteristics of high resource using children and youth: Spain. In J. W. Whittaker, J. F. Del Valle, & L. Holmes (Eds.), Therapeutic residential care with children and youth: Developing evidence-based international practice (pp. 49–62). London/Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Duffel, N. (2014). Wounded leaders: The psychohistory of British elitism and the entitlement illusion. London: Lone Arrow Press.

Eisikovits, R. A., & Beck, R. H. (1990). Models governing the education of new immigrant children in Israel. Comparative education review, 34(2), 177–196.

Eurochild. (2010). Children in alternative care-National surveys. Brussels. http://www.eurochild.org/fileadmin/user_upload

Everychild. (2011). Scaling down: Reducing, reshaping and improving residential care around the world. London: Everychild Publications. www.everychild.org.uk

Frensch, K. M., & Cameron, G. (2002). Treatment of choice or a last resort? A review of residential placements for children and youth. Child and youth care forum, 31(5), 307–339.

Gilat, M. (Ed.) (2016). Special issue on the theme: Studies, Education and Diploma: Key for changing the situation of youth at risk, Efshar, Vol. 27, May 2016 (Hebrew)

Grupper, E. (2003). Economic considerations related to the child and youth care professionalization process: The risks and the challenges. Child and youth care forum, 32(5), 271–281.

Grupper, E. (2008). New challenges for extra-familial care in Israel: Enhancing parental involvement in Education. Scottish journal of residential child care, 7(2), 14–26.

Grupper, E. (2013). The youth village: A multicultural approach to residential education and care for immigrant youth in Israel, International journal of child, youth and family studies, 2, 224-244.

Goffman, E. (1961). Asylums. New York: Anchor Books.

Islam, T., & Fulcher, L. (2016). Residential Child and Youth Care in a Developing Wirld: Global Perspectives. Cape Town, South Africa: The CYC-NET Press.

Jackson, S., & Cameron, C. (2010). Final report of the YIPPEE project WP12: Young people in public care pathways to Education in Europe.http://tcru.ioe.ac.uk/yippee. Accessed 17 June 2012.

Kashti, Y. (2000). The Israeli youth village: An experiment in training of elite and social integration. In Y. Kashti, S. Slasky, & M. Arieli (Eds.), Youth communities of youth-studies on Israeli boarding schools (pp. 27–46). Tel Aviv, Israel: Ramot-Tel Aviv University. (Hebrew).

Knorth, E. J., & Van der Ploeg, J. D. (1994). Residential care in the Netherlands and Flanders: Characteristics of admitted children and their family. International journal of comparative family and marriage, 1, 17–27.

Knorth, E. J., Harder, A. T., Zandberg, T., & Kendrick, A. J. (2008). Under one roof: A review and selective meta-analysis on the outcomes of residential child and youth care. Children and Youth Services, 30(2), 123–140.

Lifshitz, C. C., & Katz, C. (2015). Underrepresentation of Ethiopian-Israeli minority students in programs for the gifted and talented: A policy discourse analysis. Journal of Education Policy, 30(1), 101–131.

Milo-Aloni, O. (2019). “Studying in slippers”: Improving learning achievements. An original educational program in youth villages. Tel Aviv, Israel: The Administration for Residential Education, Ministry of Education. (Hebrew).

Schmid, H. (2006). Report of the public committee designed to investigate the conditions of children and youth at risk and in distress. Jerusalem: Prime Minister’s Office and Ministry of Social Welfare. (Hebrew)

Stein, M. (2006). Research review: Young people leaving care. Child and Family Social Work, 11, 276–279.

Trede, W. (2008). Residential child care in European countries: Recent trends. In F. Peters (Ed.), Residential child care and its alternatives: International perspectives (pp. 21–33). Stoke on Trent, UK: Trentham Books.

Whittaker, J. K., Holmes, L., Del Valle, J. F., et al. (2016). Therapeutic Residential Care for Children and Youth: A Consensus Statement of the International Work Group on Therapeutic Residential Care. Residential Treatment for Children, 33(2), 89–106.

Zeira, A. (2009). Alumni of educational residential settings in Israel: A cultural perspective. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 1074–1079.

Zeira, A., & Benbenishty, R. (2011). Readiness for independent living of adolescents in youth villages in Israel. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 2461–2468.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Grupper, E., Zagury, Y. (2019). Improving Academic Accomplishments of Youth in Residential Education and Care in Israel: Implementing a Policy Change. In: McNamara, P., Montserrat, C., Wise, S. (eds) Education in Out-of-Home Care. Children’s Well-Being: Indicators and Research, vol 22. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26372-0_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26372-0_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-26371-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-26372-0

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)