Abstract

The purpose of this chapter is to broaden empirical knowledge and reflect upon the importance of social skills (SS) as a critical protective factor for the social and personal well-being of secondary education students in Spain, with particular reference to academic achievement. Through guidance and teacher and student training strategies that take into account their perception of SS according to individual and context variables, the goal is to help to prevent risk situations and overcome barriers to coexistence such as risk of bullying and disruptive/aggressive behaviour. Among the main results, significant SS were identified which, being consistent with teacher expectations and specifically taught, can help prevent maladaptive behaviours, diminishing the vulnerability of certain students and optimising social relations and academic achievement. Among the prosocial behaviours with the highest potential of student well-being, which are consistent with teacher expectations, and extend beyond individual characteristics or the schools they belong to, are the SS of cooperation, responsibility and assertion. Evidence is provided in relation to guidance practice that, based on an accurate assessment of SS, contributes to educational equity to enhance students’ academic pathways and, above all, to prevent risk situations that might threaten their well-being.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

One of the main conclusions of the State Observatory for School Coexistence (Observatorio Convivencia Escolar, 2010) is that one of the most urgent and significant needs recognised by management teams and counselling departments is the need for teacher training on how to improve coexistence, with a focus on solving the issues it generates and creating student teams to improve it. It seems clear that prosocial behaviour can have an inhibiting effect on negative social behaviours and therefore it is a key factor to promote social competence in secondary education, a stage during which the development of SS plays a crucial role in social adjustment (Zsolnai, 2002) (Fig. 10.1). In the Spanish context, after considering sex and age variables, the predictive value of prosocial behaviour has been amply demonstrated in relation to the use of alcohol and cannabis, demonstrating that the likelihood of consuming these substances is lower among adolescents with positive prosocial behaviour (Redondo, Inglés, & García-Fernández, 2014).

Therefore, SS are essential in the prevention of risk conditions that increase student vulnerability in the face of social maladaptation, emotional and behavioural disorders, alcohol and drug abuse, delinquency, victimisation, violence and even a higher risk of adult psychopathologies (Coie & Dodge, 1983; Lane, Carter, Pierson, & Glaeser, 2006; Webster-Stratton, Reid, & Hammond, 2001; Walker & Severson, 2002).

In Spain, some factors strongly linked to academic success/failure are difficult to modify, such as social background which, according to the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), accounts for 50% of the differences in school performance (Enguita, Mena, & Riviere, 2010). Thus, it seems even more necessary to act upon areas that can be improved whose positive impact upon the whole class, improving school self-perception and academic self-efficacy, has been empirically demonstrated (Gutiérrez & Clemente, 1993; Garaigordobil, Cruz, & Pérez, 2003; Ray & Elliott, 2006).

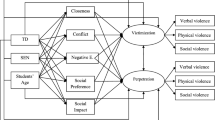

However, lack of SS has not only been related to various negative outcomes (behaviour problems, difficulties to relate to peers); the Observatory itself has highlighted the need to overcome barriers to coexistence through a comprehensive assessment of multiple indicators (Observatorio Convivencia Escolar, 2010). Among those identified, are aspects associated with academic results essential to assess coexistence (Fig. 10.2) such as student relations, interaction problems with teachers and, especially, certain violence risk factors such as being a victim/participating in situations of exclusion and humiliation as well as perceptions on disruption and discriminatory treatment.

Teachers perceive that the most frequent barrier is student disruptive behaviour (for example, disturbing, talking back or interrupting a class by talking while the teacher is explaining something). In turn, these students tend to have academic problems and experience greater difficulties in achieving ‘positive’ attention in learning, with higher rates of grade repetition, lower expectations of continuing education and lower engagement with the school.

According to Bisquerra-Alzina (1989), education must prepare human development, which also includes prevention. In educational terms, human development is related to prevention in the broad sense of the factors that may hinder it (violence, stress, anxiety, depression, risk behaviours etc.). In our current society there is a generalised loss of values, and if one aims to educate for life, a priority is to attend to emotional aspects, given that emotional education can be considered education for life.

From the perspective of a preventive-proactive counsellor (see Fig. 10.3), we should not wait until problematic behaviours emerge in class that need to be addressed with negative sanctions; rather we should be proactive and strengthen the social competences of students given their significant relationship with well-being (Uusitalo-Malmivaara & Lehto, 2013) and happiness (Garaigordobil, 2015). Inglés et al. (2009) also discuss the peer effects (positive and negative) of classmates on school achievement.

Nevertheless, SS can be learnt. At times, inhibiting social behaviours or aggressiveness can limit children’s and/or adolescents’ opportunities to bond using assertive behaviours (assertiveness). For these social relations difficulties, interventions are appropriate to teach and train the most effective skills, giving individuals the possibility of acquiring knowledge, maturity and, consequently, happiness.

The report by García-Rojas (2010) shows the results of studies proving that SS training is effective to teach children and adolescents socially effective behaviours, with an abundance of techniques, strategies and procedures that can be used to teach social interaction behaviours. These results have currently led to “many interventions being considered to teach adequate interpersonal competences to students both in compulsory and post-compulsory education” (García-Rojas, 2010, p. 229).

However, several authors have expressed their views regarding SS training in secondary education. Monjas-Casares et al. (2004) and Monjas-Casares (2006) conducted studies on adolescents and SS, showing that the youths in their studies possessed interpersonal and communication skills, and illustrated effective cognitive skills, as well as control over their own emotions and stress. According to these researchers, socially skilful adolescents have a good self-concept and high self-esteem; they also self-report positive and pleasant feelings. They are more assertive when defending their ideas, opinions and rights in a socially appropriate way without violating the rights of others. In contrast, adolescents with social skill difficulties, that is, passive, inhibited or aggressive, generally show a negative self-concept and low self-esteem. Furthermore, they self-report more feelings of loneliness or social dissatisfaction, present higher social anxiety levels and more depressive behaviours, and renounce claim to their rights or tend to assert their rights and views through aggressive behaviours” (Monjas-Casares et al., 2004, cited by Cardozo, 2012, p. 91). Other authors such as Mantilla-Castellano and Chahín-Pinzón (2006) contend that the greater the ability or skill an adolescent has to behave in the psychosocial field, such as establishing a positive relationship with themselves, with others and with the broader social environment, the more personal options they will have to achieve their goals by making a better use of available internal and external resources. Therefore, social skills, in particular empathy, must be considered a relevant factor to explain social development and social interactions (Mantilla-Castellano & Chahín-Pinzón, 2006, cited by Cardozo, 2012)

Bandura, who is regarded as the founder of social learning theory, has made important connections between the social variables of learning and behaviour both during childhood and adolescence (Bandura, 1986). As Coronel, Levin, and Mejail (2011) point out “adolescents with high academic self-esteem tend to prioritise prosocial values” (p. 246). That is, they are youths with already embedded and value prosocial behaviors. However, we can say SS are learnt in a given context and that a specific “skill may be valued by a cultural group but not another one” (Coronel, Levin, & Mejail, 2011, p. 245). In this regard, educators such as Medina-Rivilla (1988) highlighted the importance of interpersonal relations in a particular context as a key element to favour teaching-learning. Students must learn key skills to help them correctly interpret the various teaching-learning situations, to learn strategies that allow them to understand tasks and generate appropriate behaviours to adequately respond to demands placed upon them (psychosocial, personal, etc.) (Medina-Rivilla, 1988, p. 23).

Therefore, following research by García-Jiménez, García-Pastor, and Rodríguez-Gómez (1992–1993), experts have shown that one of the main flaws of students with sociocultural handicaps is the development of social skills and processing social information. Research in this field has demonstrated how the lack of social skills is one of the causes of existing conflicts with classmates, teachers and authorities, and how strategies focused only on class control do not necessarily generate greater interest in learning.

However, this raises the question of which SS are the most significant and have greater potential to diminish the vulnerability of students in secondary education, optimise their social relations and promote their academic success according to their teachers. To identify which are the critical SS for student academic achievement, and to verify the possible impact of individual and context variables, are significant objectives. Since teachers are privileged agents in the promotion of cooperative structures and optimal social relations, they can foster an interest in learning and, with this, prevent risk situations and academic failure for their students.

2 Methodology/Development

Through non-probability sampling, due to accessibility, we selected a sample of 198 teachers working in schools from all the Spanish Autonomous Communities, except Navarre, Extremadura, Ceuta and Melilla. There was a predominance of female teachers (60.1%) from public schools (78.8%) and with over ten years of experience (66.2%), essentially in upper secondary (37.9%) and lower secondary education (31.8%) levels.

To identify the critical SS, we used the Spanish adaptation of the Social Skills Improvement System (SSIS) created by Gresham and Elliott (2008). After adapting it to the Spanish cultural context, we obtained a scale made up of 46 items and seven dimensions (Communication, Cooperation, Assertion, Responsibility, Empathy, Extroversion and Self-Control) ranked on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Very Low and 5 = Very High).

Through descriptive and essentially non-parametric statistical procedures (Chi-squared, Kruskal-Wallis tests, Median and Mann-Whitney’s U) implemented with SPSS (version 19), we evaluated the degree of importance of each dimension of the SS as well as the existence or not of significant differences in said dimensions based both on individual teacher variables (i.e. sex, years of experience) and on context variables (type of school, stage they teach).

3 Results/Discussion

The following are some of the main results. The sample of teachers surveyed estimated that all SS dimensions of the SSIS are crucial for academic achievement, with no significant differences found by stages (lower secondary education, upper secondary education, vocational education and training). However, there were some SS that were more important in upper secondary education than in Vocational Education and Training (VET), such as respecting turns to speak or joining ongoing activities, whilst activities identified as more important in VET than in upper secondary education were maintaining eye contact, accepting feedback or resolving conflicts calmly.

Individual teacher characteristics such as sex did show certain significant differences: female teachers particularly valued communication SS while male teachers placed more emphasis on assertion. Finally, compared to their peers with intermediate experience, teachers in public schools with over ten years of experience significantly underestimated students’ ability to behave well without teacher supervision (i.e. Responsibility), as well as the ability to introduce themselves to others on their own initiative (i.e. Extroversion).

4 Conclusions/Proposals

The empirical evidence provided in this chapter ratifies previous studies by Gresham et al. (2000), Lane, Wehby, and Cooley (2006), Lane, Pierson, Stang, and Carter (2010), demonstrating the consistency of teacher expectations about the importance of their students’ SS, particularly for academic achievement. Therefore, we found a repetition of the importance of cooperation and self-control (Lane et al., 2010), although it is striking that Spanish teachers expressed a higher value for Assertion than Self-Control compared to their American peers, which may be due to cultural differences and expectations.

Especially noteworthy were certain critical SS that if acquired could improve students’ ability to respond to the specific demands of their educational contexts, reducing risk situations and enhancing their interest to learn. Mastering the SS that teachers value because they help establish a good learning environment in class is a true ‘protective factor’ that also promotes students’ well-being, is directly related to Cooperation and Responsibility (following instructions, performing tasks without disturbing others, respecting group rules, behaving well without teacher supervision, respecting others’ property) and is incompatible with disruptive behaviours towards teachers and mistreatment of other students (for example, due to their diverse origins, culture, special educational needs etc.). Even the highest valued Assertion SS are directly related to students’ ability to express their problems, defend themselves, ask for help or share feelings which would allow them to avoid/resolve conflicts, for example, bullying and reducing the risk of being chosen as a victim.

Consequently, when verifying that the SS precisely most valued by teachers also appear to play a significant role to eradicate risk situations and improve coexistence quality according to the School Coexistence Observatory (Observatorio Convivencia Escolar, 2010), it would be reasonable to prioritise this type of SS in individual or group intervention strategies but always for counselling and training students and teachers because, although schools have significantly incorporated the teaching of these skills, this should be reinforced so SS are properly used by all students in all schools. Socially and emotionally competent teachers develop supporting relationships with their students and create activities to help them acquire the SS needed in class based upon their own strengths (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009).

References

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bisquerra Alzina, R. (1989). Introducción conceptual al análisis multivariable: Un enfoque con los paquetes estadísticos SPSS-X, BMDP, LISREL y SPAD. Barcelona, Spain: PPU.

Cardozo, G. (2012). Habilidades para la Vida en adolescentes: Factores Predictores de la Empatía. Anuario de Investigaciones de la Facultad de Psicología, 1(1), 83–93.

Coie, J. D., & Dodge, K. A. (1983). Continuity of children’s social status: A five-year longitudinal study. Merrill-Palmer Querterly, 29, 261–281.

Coronel, C. P., Levin, M., & Mejail, S. (2011). Las habilidades sociales en adolescentes tempranos de diferentes contextos socioeconómicos. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 9(23), 241–261.

Enguita, F., Mena, L., & Riviere, J. (2010). Fracaso y abandono escolar en España. Colección Estudios Sociales 29. Barcelona: Fundación La Caixa.

Garaigordobil, M. (2015). Predictor variables of happiness and its connection with risk and protective factor for health. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1176. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01176.

Garaigordobil, M., Cruz, S., & Pérez, J. I. (2003). Análisis correlacional y predictivo del autoconcepto con otros factores conductuales, cognitivos y emocionales de la personalidad durante la adolescencia. Estudios de Psicología, 24, 113–134.

García Jiménez, E., García Pastor, C., & Rodríguez Gómez, G. (1992–1993). Limitaciones del constructo “habilidades sociales” para la elaboración de un modelo de intervención social en el aula. Enseñanza & Teaching, 10–11, 293–310.

García Rojas, A. (2010). Estudio sobre la asertividad y las habilidades sociales en el alumnado de Educación Social. Revista de Educación, 12, 225–240.

Gresham, F. M., Dolstra, L., Lambros, K. M., McGlaughlin, V., & Lane, K. L. (2000). Teacher expected model behavior profiles: Changes over time. Scottsdale, AZ: Paper presented at Teacher Educators for Children with Behavioral Disorders.

Gresham, F. M., & Elliott, S. N. (2008). Social Skills Improvement System (SSIS). Rating Scales Manual. Green Valley Drive Bloomington, MN: PsychCorp, Pearson.

Gutiérrez, M., & Clemente, A. (1993). Autoconcepto & conducta prosocial en la adolescencia temprana. Bases para la intervención. Revista de Psicología de la Educación, 4, 39–48.

Inglés, C. J., Benavides, G., Redondo, J., García-Fernández, J. M., Ruiz-Esteban, C., Estévez, C., et al. (2009). Conducta prosocial y rendimiento académico en estudiantes españoles de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Anales de Psicología, 25(1), 93–101.

Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79, 491–525.

Lane, K. L., Carter, E. W., Pierson, M. R., & Glaeser, B. C. (2006a). Academic, social, and behavioral characteristics of high school students with emotional disturbances or learning disabilities. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 14, 108–117.

Lane, K. L., Pierson, M. R., Stang, K. K., & Carter, E. W. (2010). Teacher expectations of student’s classroom behavior. Remedial and Special Education, 10(3), 163–174.

Lane, K. L., Wehby, J. H., & Cooley, C. (2006b). Teacher expectations of students’ classroom behavior across the grade span: Which social skills are necessary for success? Exceptional Children, 72(2), 153–167.

Mantilla Castellano, L., & Chahín Pinzón, I. (2006). Habilidades para la vida. Manual para aprenderlas y enseñarlas. Bilbao, Spain: EDEX.

Medina Rivilla, A. (1988). Didáctica e interacción en el aula. Madrid, Spain: Cincel.

Monjas Casares, M. (2006). Estrategias de Prevención del acoso escolar. Ponencia del II Congreso Virtual de Educación en Valores “El acoso escolar, un reto para la convivencia en el centro”. http://www.unizar.es/cviev/.

Monjas Casares, M., García Larrauri, B., Elices Simón, J., Francia Conde, M., & Benito Pascual, M. (2004). Ni sumisas ni dominantes. Los estilos de relación interpersonal en la infancia y en la adolescencia (Memoria de Investigación Nº 207-05-059-2). España: Plan Nacional de Investigación Científica, Desarrollo, e Innovación Tecnológica. Ministerio de Trabajo y Asuntos Sociales.

Observatorio Convivencia Escolar. (2010). Estudio estatal sobre la convivencia escolar en la Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Madrid, Spain: Ministerio de Educación, Secretaría General Técnica.

Ray, C. E., & Elliott, S. N. (2006). Social adjustment and academic achievement: A predictive model for students with diverse academic and behavior competencies. School Psychology Review, 35(3), 493–501.

Redondo, J., Inglés, C., & García-Fernández, J. M. (2014). Conducta prosocial y autoatribuciones académicas en Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Anales de psicología, 30(2), 482–489.

Uusitalo-Malmivaara, L., & Lehto, J. E. (2013). Social factors explaining children’s subjective happiness and depressive symptoms. Social Indicators Research, 111, 603–615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0022-z.

Walker, H. M., & Severson, H. H. (2002). Developmental prevention of at-risk outcomes for vulnerable antisocial children and youth. In K. L. Lane, F. M. Gresham, & T. E. O’Shaughnessy (Eds.), Children with or at risk of emotional and behavioral disorders (pp. 177–194). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Webster-Stratton, C., Reid, J., & Hammond, M. (2001). Social skills and problem-solving training for children with early-onset conduct problems: Who benefits? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42, 943–952. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00790.

Zsolnai, A. (2002). Relationship between children’s social competence, learning, motivation and school achievement. Educational Psychology, 22, 317–329.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

García-Salguero, B., Mudarra, M.J. (2020). Importance of Social Skills in the Prevention of Risk Situations and Academic Achievement in Secondary Education in Spain: What Do Teachers Expect from Their Students? How Can Coexistence and Well-Being Be Improved?. In: Malik-Liévano, B., Álvarez-González, B., Sánchez-García, M.F., Irving, B.A. (eds) International Perspectives on Research in Educational and Career Guidance. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26135-1_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26135-1_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-26134-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-26135-1

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)