Abstract

Episodic memory has been conceptualized as the memory for personal events with specific spatiotemporal components. The assessment of episodic memory is usually conducted by means of verbal recall tasks, in which the individual is required to repeat what (s)he remembers from a previously presented verbal material (either single words or a brief story). However, the need of a more ecological approach to memory assessment led researchers to investigate the potential use of 360° videos as a suitable tool to present real life scenes to be remembered. The present study presents the protocol of the assessment of episodic memory employing five 360° video that represent interpersonal, emotional experiences known to be altered in psychopathological conditions. Furthermore, a case study in which the assessment protocol is applied to a patient with Borderline Personality Disorder is described. The results of the case study seem to indicate that our 360° videos are able to detect anomalies in remembering the behaviors displayed, the connected emotion together with details regarding the “where” and “when” components of the episodic recall.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

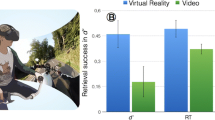

A more ecological evaluation of episodic memory has challenged both researchers and clinicians in the last 20 years. From the pivotal definition of Tulving [1, 2], episodic memory has been traditionally conceptualized as the memory for personally first-person perspective events, with a specific spatiotemporal context. Typically, verbal paradigms are used to evaluate episodic memory function: participants are invited to remember a list of words, and then they are tested on that specific list. However, the need for a more naturalist approach to memory recently emerges, along with the use of self-relevant and everyday material, able to predict behaviors also in real-life contexts [3, 4]. A first trend is the use of Virtual Reality (VR) technology for developing an innovative assessment of episodic memory simulating everyday activities, but maintain also a strict control over the stimuli delivery [5,6,7]. Thanks to the use of VR, participants are completely immersed in highly ecological environments (i.e., a city, a park,) where it is possible to easily insert everyday events experienced in first-person perspective with their perceptual and affective details (i.e., a lady with a crying baby, a group of children playing soccer, etc.). Interesting examples were offered in Piolino’s works [8,9,10,11]. In particular, Plancher et al. [11] exploited the potentiality of VR-based tools to better understand the cognitive profile of patients suffering from mild cognitive impairments and Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). Participants were immersed in a virtual city (either in passive or active navigation) to remember a series of events; consistently with literature, they found that a deficit in remembering personally experienced events for patients with AD, but they also noted that active navigation was able to improve performance for all groups.

A more recent trend for the ecological evaluation of episodic memory function is the possibility to immerse participants in real environments and explore them from a first-person perspective thanks to the use of 360° technology [12, 13]. This technology records a circular fisheye view of the environment, and then participants can easily view the realistic 360° scenarios with a tablet (i.e., non immersive experience) or through a head mounted display (i.e., immersive experience). 360° technology allows the assessment of mnestic processes in a controlled and safe setting within real-life scenarios [13]. Moreover, it is a quite affordable technology, without any specific technical skills to be mastered. In the current work, we exploited the potentiality of 360° technology for episodic memory assessment focusing on individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD). We studied BPD since previous studies have found specific memory biases in autobiographical recall for these patients [14, 15]. In particular, Winter et al. [16] highlighted the presence of a negative evaluation bias for positive, self-referential information in BPD. This bias did not influence the ability to store personal information, but their quality: it is related to self-attributions of negative events in daily life situations.

2 Methods

2.1 Materials

Five 360° videos were recorded for the purpose of the study. 360° videos are special videos recorded by omnidirectional cameras that capture images from all the space around. These videos can be played by wearing a head-mounted display (HMD) or they can be visualized by means of a smartphone provided with gyroscope and combined with a cardboard. Anyway, the user can explore the environment represented within the video by turning the head up-down-left and right, but (s)he cannot select the direction of the navigation (the navigation path is determined at the moment of the recording). Each video had been recorded in a different environment and included four actors, one of whom was always silent. The other three interacted among each other and the conversation focused on a specific topic, which constituted the core material to be remembered. Indeed, the content of four out of five video was a description of an interpersonal, emotional experience that is known to be altered in psychopathological conditions. In these videos functional and suitable behaviors are depicted in contexts of social and interpersonal relations challenging the coping abilities of psychopathological patients. The fifth video represented a control condition, in which a situation without emotional load and describing a very neutral personal exchange among characters is described. Table 1 illustrates the specific content of each video. Videos duration ranged from 40 s to 1 min and 10 s.

2.2 Protocol

The study is composed by two independent sessions that take place in different days to avoid interference effects of the materials. The order of the sessions is interchangeable and is counterbalanced across participants.

Neuropsychological Assessment.

All the participants undergo a brief neuropsychological assessment to evaluate basic cognitive abilities. The battery includes an evaluation of short and long-term verbal memory [story recall “Anna Pesenti”, [17]], sustained attention [Attention Matrices, [17]], attention shifting [Trail Making Test [18]] and verbal fluency with both semantic and phonetic cues [17].

Immersive Episodic Memory Assessment.

At the beginning of this session the participant is introduced to the use of the cardboard/HMD and the 360° videos. Specifically, the experimenter illustrates the exploration capabilities of the device, underscoring the fact that the movement of the head allows the visualization of the correspondent portion of the environment. When the participant demonstrates to be familiar with the equipment the video administration can start. The experimenter provides the participants the following instructions: “now you will be presented with 5 videos, each one set in a different location and involving 4 actors. Your job is to pay attention to the content of the conversation, to who is speaking and what (s)he is saying, and to whatever detail of the video. Upon video visualization, I will ask you to tell me what you remember”. All the videos are presented without breaks in the between, but before playing each video the experimenter clearly claims the video’s title. The order of presentation is counterbalanced across participants, so that each video is seen in each of the five available positions. At the end of the last video, the Free Recall test starts. The participant is invited to described what (s)he remembers of each of the video presented, following the same presentation order. The recall is audiotaped. Afterwards, the Cued Recall is administered. This test includes 5 questions for each video, exploring the following topics: 1. the general content of the dialogue; 2. some details of the dialogue; 3. the spatial disposition of the actors; 4. the attitude of one of the characters; 5. the timing of a given episode. The next step is the administration of a 3-questions survey investigating the following: 1. the extent to which while remembering the video the participant had the subjective impression to re-live the experience; 2. the evaluation of the valence of the emotion mostly represented within the video; 3. the name of the emotion mostly represented within the video. After a delay of 30 min, the Free Recall is repeated (Delayed Free Recall). During the pause, the participants undergo an activity not involving memory abilities. Figure 1 depicts the experimental protocol.

Tests Scoring.

The Free Recall grid score (see Table 2) includes 4 categories:

-

a.

Main event represented: for each video 4 main elements, essential to understand and describe the content of the conversation, had been identified (see the list on Table 2). The score ranges from 0 to 4 according to the number of elements remembered.

-

b.

Actors: the identity and number of actors represented in the video should be reported (score: 0–4)

-

c.

Details: whatever detail remembered is worth 1 point (i.e.: specific people named during the conversation; details of the environment in which the scene is played, details about the actors, such as clothing, physical features; position of the actors); if the egocentric position of the actors is reported 1 additional point is attributed.

-

d.

Errors: false memories are also recorded

The Cued Recall questionnaire is scored assigning 1 point to each correct response (range: 0–20).

The post-video survey has 2 five- points Likert questions [n.1], “have you got the impression to remember the details as if your were re-living the scene in your mind?” ranging from 1 (not al all) to 5 (very much); n.2 “how do you rate the emotion emerging from the interaction among actors?” ranging from 1 (very negative) to 5 (very positive). The last question is open and the participant has to write down the name of the prevalent emotion recognized in the video.

3 Case Study

Claudia (a pseudonym) is a 19-years-old university student. Her family is composed by mother, father and a 33-years-old brother who had problems with drug addiction up to 3 years ago. She reports that he has begun to experience frequent and apparently unexplained headaches, sudden hand and jaw tremors, and heartbeat acceleration; for these reasons she carried out various investigations (MRI and blood tests) which, however, have not highlighted any problem. Although the symptoms are obvious, C. feels misunderstood. C. has been engaged for two years with A. He reports that he has a good relationship with the boy, even if he does not really understand her current state of suffering and distress. Presently, the girl has no friends, except for two schoolmates with whom she rarely talks. She tells of having gone through a difficult childhood and adolescence: indeed, during the years of elementary and middle schools her commitment was devalued and her difficulties, caused by strabismus, were confused with a lack of commitment and will. She is currently treated by a psychiatrist with paroxetine and diazepam; at the same time she is undergoing a psychotherapy with a male therapist she trusts a lot.

3.1 Psychological Examination

C. arrives at the evaluation on request of the psychiatrist. She is collaborative. The facial expression is marked by anxiety and restlessness. The state of consciousness is alert and sufficiently oriented in time and space. The course of thought is accelerated (tachipsychism) with frequent logical jumps, while the thought form is characterized by derailment (ideas deviate in a direction not apparently connected with the concept of departure) and tangentiality (response whose content is marginally, remotely or nothing at all related to the question). The language is characterized by logorrhea and incongruous syntax with respect to age and education (verbs declined incorrectly, need to repeat several times the questions, due to incongruent answers). She reports some disperceptive phenomena (auditory hallucinations: misperception of children voices in the street; perceptive hallucinations: moving objects; belief of being able to move objects with thought). The mood is labile (rapid alternation of opposite emotions - sudden transition from crying to smile) and dysphoric, characterized by variations due to low-relevance stimuli (access of uncontrolled rage). Furthermore, a marked anxious symptomatology is detected, characterized by agitation, restlessness, tension, fatigue and difficulty in concentration; in addition, a panic disorder with agoraphobia emerges. Current suicidal risk is high, and some suicide attempts are reported (strangulation with a headscarf).

The psychodiagnostic examination includes the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES-II; [19]), the Symptom Checklist-90-R (SCL-90, [20]) and the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM (SCID-II, [21]). The DES-II score is 57.14, indicative of numerous dissociative experiences. In the SCL-90 the patient obtained the highest scores in the following symptomatological dimensions: somatization (score = 41), obsession-compulsivity (score = 31), depression (score = 38), anxiety (score = 27), and psychoticism (score = 22). The Global Severity Index (GSI), indicating the intensity of the psychological distress level complained of by the patient, is 2.61; the Positive Symptom Total (PST), that describes the number of symptoms reported by the subject, is 9; the Positive Symptom Distress Index (PSDI), indicating the response style index, is 2.9. The SCID-II questionnaire underscores the presence of a Borderline Personality Disorder. At least, five criteria are needed for the diagnosis of the Borderline Personality Disorder (BDP).

As a result of the clinical and psychodiagnostic examination the patient appears to meet 7 criteria of the Borderline Personality Disorder (BDP). The patient is characterized by:

-

A pattern of unstable and intense interpersonal relationships, characterized by the alternation between extremes of hyperidealization and devaluation.

-

Alteration of identity: self-image or self-perceptions markedly and persistently unstable.

-

Recurrent behaviour or suicidal threats, and self-mutilating behaviour (self-harm, cuts on arms and legs, cigarette burns).

-

Affective instability due to marked mood reactivity (e.g. episodic intense dysphoria, irritability or anxiety, which usually lasts a few hours, and only rarely more than a few days).

-

Chronic feelings of emptiness.

-

Inappropriate, intense anger, or difficulty controlling anger (e.g. frequent anger or constant anger, recurring physical fights).

-

Transitional paranoid ideation, associated with stress, or severe dissociative symptoms.

3.2 Immersive Episodic Memory Assessment: Results and Discussion

Table 2 displays the summary of the Free Recall and Delayed Free Recall. Figure 2 represents the patient’s performance in the Cued Recall task.

For what concerns the post-video survey, only the third question (the open one, investigating the prevalent emotion detected in each video) will be considered here. C. identified the following emotions: fear (UNIVERSITY), anger (HOUSE), anger and compassion (COURTYARD), sadness (ORAL EXAM), and happiness (OFFICE).

As for the Free Recall, the patient remembered less than the 75% of the items pertaining the Main Event, at both the time points; the performance was better for the recall of the actors involved in the scenes (the characters not reported were usually those silent). Furthermore, more details as well as more errors were reported in the Delayed compared to the immediate recall. Looking at the differences among videos, it seems clear that in particular that titled “House” was less accurately recalled. Indeed, when describing the content of this video, C. missed all but one of the important elements of the conversation. This could indicate a specific difficulty in integrating coherently in personal memory behaviors demonstrating functional coping abilities in managing potential conflicting situations (of note, this specific video described a situation in which different points of view are presented and discussed respectfully, without anger). In the Cued Recall C. seemed to have more difficulties in remembering the “where” and “when” components of the episodic event, and the worst performance was obtained in the HOUSE (coherently with the Free Recall) and OFFICE videos. The post-video survey confirmed that C. is barely able to recognize the emotions and to catch the correct emotional content of the events represented. This is particularly true for the HOUSE video, in which C. states to have identified anger, but the actors discussed in a very respectful and calm way. Indeed, a recent study by Niedtfeld and colleagues [22] explained difficulties in emotional recognition in PBD with a general deficits in integrating social signals (i.e. speech content, variation in prosody, and facial expression) in a coherent way. Participants were invited to identify emotions in different short video clips (adapted from [23]) showing a person telling a self-related story. These video clips were specifically manipulated to represent different combinations of the three social signals: facial expression, speech content, and prosody. They found that PBD patients made more errors in emotion recognition compared to healthy controls whenever stimuli contained only facial expressions, and for combination of all three communication channels.

In conclusion, this case study demonstrates that the 360° videos were able to detect anomalies in remembering the behaviors displayed, the connected emotion together with details regarding the “where” and “when” components of the episodic recall. Further studies, with psychiatric samples compared to healthy controls will inform about the reliability of this immersive episodic memory test, possibly allowing to classify different types of diagnoses based on the different performances at the different videos.

References

Tulving, E.: Episodic memory: from mind to brain. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 53, 1–25 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135114

Tulving, E.: Episodic memory and common sense: how far apart? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 356, 1505–1515 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2001.0937

Parsons, T.D.: Virtual reality for enhanced ecological validity and experimental control in the clinical, affective and social neurosciences. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9, 660 (2015). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00660

Parsons, T.D., Carlew, A.R., Magtoto, J., Stonecipher, K.: The potential of function-led virtual environments for ecologically valid measures of executive function in experimental and clinical neuropsychology. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 27, 777–807 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2015.1109524

Bohil, C.J., Alicea, B., Biocca, F.A.: Virtual reality in neuroscience research and therapy. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12, 752–762 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3122nrn3122

Parsons, T.D., Gaggioli, A., Riva, G.: Virtual reality for research in social neuroscience. Brain Sci. 7 (2017). https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci7040042

Rizzo, A.A., Schultheis, M., Kerns, K.A., Mateer, C.: Analysis of assets for virtual reality applications in neuropsychology. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 14, 207–239 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010343000183

Compère, L., et al.: Gender identity better than sex explains individual differences in episodic and semantic components of autobiographical memory and future thinking. Conscious. Cogn. 57, 1–19 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CONCOG.2017.11.001

Plancher, G., Gyselinck, V., Nicolas, S., Piolino, P.: Age effect on components of episodic memory and feature binding: a virtual reality study. Neuropsychology 24, 379–390 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018680

Plancher, G., Gyselinck, V., Piolino, P.: The integration of realistic episodic memories relies on different working memory processes: evidence from virtual navigation. Front. Psychol. 9, 47 (2018). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00047

Plancher, G., Tirard, A., Gyselinck, V., Nicolas, S., Piolino, P.: Using virtual reality to characterize episodic memory profiles in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: influence of active and passive encoding. Neuropsychologia 50, 592–602 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.12.013

Negro Cousa, E., Brivio, E., Serino, S., Heboyan, V., Riva, G., de Leo, G.: New frontiers for cognitive assessment: an exploratory study of the potentiality of 360° technologies for memory evaluation. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. Cyber. 2017, 0720 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0720

Serino, S., Repetto, C.: New trends in episodic memory assessment: immersive 360° ecological videos. Front. Psychol. 9, 1878 (2018). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01878

Minzenberg, M.J., Fisher-Irving, M., Poole, J.H., Vinogradov, S.: Reduced self-referential source memory performance is associated with interpersonal dysfunction in borderline personality disorder. J. Pers. Disord. 20, 42–54 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2006.20.1.42

Schnell, K., Dietrich, T., Schnitker, R., Daumann, J., Herpertz, S.C.: Processing of autobiographical memory retrieval cues in borderline personality disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 97, 253–259 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAD.2006.05.035

Winter, D., Herbert, C., Koplin, K., Schmahl, C., Bohus, M., Lis, S.: Negative evaluation bias for positive self-referential information in borderline personality disorder. PLoS ONE 10, e0117083 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117083

Spinnler, H., Tognoni, G.: Italian group on the neuropsychological study of ageing: Italian standardization and classification of neuropsychological tests. Ital. J. Neurol. Sci. 8, 1–120 (1987)

Giovagnoli, A.R., Del Pesce, M., Mascheroni, S., Simoncelli, M., Laiacona, M., Capitani, E.: Trail making test: normative values from 287 normal adult controls. Ital. J. Neurol. Sci. 17, 305–309 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01997792

Schimmenti, A.: Dissociative experiences and dissociative minds: exploring a nomological network of dissociative functioning. J. Trauma Dissociation. 17, 338–361 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2015.1108948

Derogatis, L.R.: Symptom Checklist-90-R: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual, 3rd edn. National Computer Systems, Minneapolis (1994)

First, M.B.: Structured clinical interview for the DSM (SCID). In: The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology, pp. 1–6. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken (2015)

Niedtfeld, I., et al.: Facing the problem: impaired emotion recognition during multimodal social information processing in borderline personality disorder. J. Pers. Disord. 31, 273–288 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2016_30_248

Regenbogen, C., et al.: The differential contribution of facial expressions, prosody, and speech content to empathy. Cogn. Emot. 26, 995–1014 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2011.631296

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 ICST Institute for Computer Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering

About this paper

Cite this paper

Repetto, C. et al. (2019). Immersive Episodic Memory Assessment with 360° Videos: The Protocol and a Case Study. In: Cipresso, P., Serino, S., Villani, D. (eds) Pervasive Computing Paradigms for Mental Health. MindCare 2019. Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering, vol 288. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25872-6_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25872-6_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-25871-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-25872-6

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)