Abstract

This chapter examines emotional labor in the Philippines, an archipelagic nation in the Pacific with a population of over 100 million people. A blend of multiple cultures and influences, its contemporary civil service borrows heavily from US public administration and overlays these with traditional and acquired cultural characteristics. Empirical evidence shows that in some ways, emotional labor in the Philippine public sector mirrors that of other countries, but its relationship to job-related outcomes may reflect its own particular culture and context. Emotive capacity relates positively with job satisfaction and personal fulfillment like in many other countries. Emotive pretending while performing one’s job duties has no effect on burnout, unlike in many other countries. Performing authentically—deep acting—has no relationship with job satisfaction and personal fulfillment, but it is positively related to burnout. This is unlike the Philippine private sector, where deep acting was previously found to reduce burnout. Cultural and contextual factors in the Philippine public sector may help to explain these findings.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Emotional labor in the public sector is an emerging topic raising significant interest not only in the USA but also elsewhere in the world. The concept emotional labor was coined by Hochschild (1983) and is defined as “the process by which workers are expected to manage their feelings in accordance with organizationally defined rules and guidelines” (Wharton2009, 147). Emotional labor is typically described in terms of two types: surface acting, or pretending to feel a certain emotion, and deep acting where workers experience the emotions they are required to show. The interest in emotional labor in the public sector stems partially from the realization that many, if not most, public service jobs require interpersonal contact with the public (Guy et al. 2008). This means that most government employees must manage their emotions in order to perform their jobs effectively.

While public administration in the Philippines often follows the trends and developments in American public administration, there is often a delay before these take root. For example, reforms influenced by the Reinventing Government and New Public Management movements in the USA were adopted in the Philippine civil service only in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Recent initiatives focus on the harmonization of performance evaluation systems and the adoption of new performance management systems (see, e.g., Torneo et al.2017a, b). While discussions of emotional labor in the public sector have gained significant traction elsewhere, it has not yet taken root in the Philippines. As of this writing, there is no publicly available research on emotional labor in the Philippine public sector.

A handful of studies and a thesis pertaining to emotional labor in the Philippines have been conducted, but they focus on service industries in the private sector. For example, Barcebal et al. (2010) unpublished research examined the effect of emotional labor on the burnout level of 159 frontline employees from several types of service organizations in the Philippines, including airline, food, academe, and call center work. Additionally, Ruppel et al. (2013) research examined emotional labor in the context of a call center in the Philippines. Sia’s (2016) work focused on the influence of emotional labor on the work and personal life of employees in a franchise industry setting in the Philippines. Newnham’s (2017) more recent study examines and compares the enactment and consequences of emotional labor among frontline hotel workers in the Philippines and Australia.

Barcebal et al. (2010) found that surface acting, but not deep acting, is related to burnout and exhaustion of Filipino service sector employees. These workers engage in more deep acting than surface acting. Ruppel et al. (2013) found that Filipino “call centre employees reported emotional stress, leading to job dissatisfaction, reduced organization commitment and ultimately increased intention to turnover” (246). Newnham (2017) found that both Australian and Filipino workers report higher levels of burnout when using surface acting and lower levels of burnout when using deep acting more often. Respondents in both countries experience similar levels of deep acting and burnout, and those who report high job autonomy also report lower levels of burnout. Higher levels of burnout are reported by individualists who use surface acting more frequently.

The growing global interest in emotional labor in public sector organizations is a significant development since public service delivery often involves the management of emotions. However, the general lack of awareness on emotional labor in the Philippine civil service is regrettable. This aspect of the work is not acknowledged, compensated, or rewarded, and mechanisms to help government employees deal with this aspect of their work are not in place. Thus, Filipino government employees tend to deal with consequences of emotional labor such as stress and burnout on their own. This chapter is an attempt to add to the literature on this topic and to contribute for improving human resource policy in the Philippine public sector.

Overview of the Philippine Civil Service

The Philippines is an archipelagic country of 7641 islands in the Pacific with an estimated national population of 107.7 million as of 2019. It is a developing country with a medium-sized economy and is a founding member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Geographically, it is divided into three major island groups called Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao and has seventeen administrative regions. It has a presidential and unitary form of government largely patterned after the American system with powers divided among the executive, the bicameral legislature, and the judiciary. The official languages are Filipino and English, but there are eight major languages spoken and at least 120 languages and dialects in use. The country has a significant diaspora resulting in around 10.2 million people of Filipino descent living outside of the country. At least 2.3 million Filipinos are overseas migrant workers.

Modern-day Philippine civil service is guided by the Administrative Code of 1987. The civil service was shaped by American traditions of public administration, and there is a strong emphasis on the principles of merit and professionalism. Applicants need to pass the Civil Service Examinations (CSE) to be eligible for government employment and tenure. Those aspiring to senior career service positions need to pass rigorous exams to attain Career Executive Service Officer (CESO) eligibility and/or need to possess recognized graduate degrees or qualifications. Many top-level positions, however, are appointed at the discretion of the President, and the number of direct and indirect appointees exceeds 7500 (Hodder2009). Senior officials, such as cabinet and sub-cabinet members and local chief executives, can also freely appoint people in confidential positions involving personal trust. The government also hires temporary consultants and contractual personnel to fill its staffing needs.

Given its substantial population, archipelagic geography, and rapidly growing economy, the size of the Philippine civil service is also proportionally large. The bureaucracy is composed of around 2,420,892 employees distributed among various national government agencies, state universities and colleges, local water districts, local government units, and government-owned and controlled corporations (Civil Service Commission 2017). Of this number, 1,569,585 are career service personnel, 190,917 are noncareer service personnel, and 660,390 are Job-Order or Contract of Service personnel. National government agencies are estimated to employ a total of 1,146,337 first and second level employees. Table 15.1 shows the distribution of first and second level employees. First level jobs are clerical, trades, crafts, and custodial service positions which involve non-professional or sub-professional work. Qualifications for first level jobs require less than a college degree. Second level jobs are professional, technical, and scientific positions. Qualifications for these jobs require at least a college degree.

Among the national agencies, the largest share of employees can be found in the Department of Education, which employs nearly 600,000 public-school teachers and non-teaching personnel. Beyond that department, the Department of Interior and Local Government and attached agencies employ approximately 170,000 police and non-police personnel in the Philippine National Police, along with 4247 civilian employees. There are 22,062 personnel in the Bureau of Fire Protection, along with 11,217 personnel in the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology. Additionally, there are thousands of personnel in other units according to the Civil Service Commission’s 2017human resources inventory.

Government-owned and controlled corporations employ 66,577 personnel, state universities, and colleges employ 57,450 personnel, and local water districts employ around 14,621 personnel. Local government units also employ large numbers of personnel since they are at the frontline of public service delivery. The total number of personnel employed by local governments is estimated at around 284,600. As of 2017, these personnel are distributed among the Philippines’ 81 provinces, 145 cities, 1489 municipalities, and 42,036 barangays at the village level. The official estimated number of personnel for local government units is likely at the conservative side given the common practice of hiring contractual workers and volunteer workers (e.g., Barangay Health Workers) to fill shortages in staffing at the local level.

History of the Philippine Civil Service

Much of the modern-day Philippine civil service systems and structures are patterned after that of the USA, but traces of its pre-colonial history and colonial influences from Spain remain. Prior to Spanish occupation in the seventeenth century, the various islands of the Philippines may be described as autonomous proto-states governed by native leaders called sultans, datus, and rajas under a politico-administrative system with Islamic and Indian influences. The basic political and administrative unit at the village level was called a balangay headed by a village leader or datu. As well, native kingdoms and sultanates also existed under the leadership of more powerful leaders of which there were several. Without a single ruler and with varying languages and culture, relationships between the island proto-states were fluid and were characterized by trade, competition, cooperation, and conflicts.

Political and administrative leadership in the villages were held by the datu and supported by a council of elders. The datu had near unlimited authority and was responsible for defending the community, administering justice, arbitrating conflicts, deciding on the use of communal lands, collecting tributes, and delivering services. A legal system also existed governing ownership of property, inheritance, marriage, rights and obligations, and individual behavior (Abueva1988; De la Torre1986). Some regions in Mindanao acquired more power, wealth, and territory and developed into sultanates. Reyes (2011), however, notes that these communities were not able to lay down the foundations of an established bureaucracy, even when these cohesive communities were governed by internal rules and practices and demonstrated political and economic organization and relatively mature culture and institutions.

Spain established a colonial form of government when it gained control over most of the Philippine islands in the seventeenth century. During this period, Spaniards were a privileged class and held the top political and administrative positions in the colonial government. Spanish mestizos also occupied privileged positions well above most natives and migrants in the colony. The colonial government was headed by a Gobernador-General representing the Spanish monarchy. A variety of colonial positions such as those of viceroy, members of the supreme court, and provincial executives were also granted based on grants or favors from the monarchy. Catholic friars held very strong influence over not only the religious and socio-cultural life, but also the political and administrative life in the colony (e.g., see Corpuz1957; Endriga2003).

During this time, many positions in the colonial government were sold to the highest bidder (Corpuz1957). The administrative system that Spain established was primarily designed with the “practical objective of increasing the royal estate through tributes, monopolies, fees and fines” (Endriga2003, 394). The highest position that natives could attain was the gobernadorcillo, which fused political, economic, administrative, and judicialleadership. At the village level were units called pueblosor barrios (Abueva1988) headed by cabeza de barangay or teniente del barrio. Spain ruled the islands, which it named Las Islas Filipinas, after the Spanish King Felipe II, for 333 years, until the impending threats of the Philippine Revolution and the challenge of rising US colonial ambitions forced it to cede the colony to the latter in exchange for twenty million dollars in the 1898 Treaty of Paris.

Prior to American colonization, natives waged war against Spain and had established a revolutionary form of government. Filipino revolutionaries had already surrounded the capital of the Spanish colonial government in Intramuros, Manila, before the surprise landing of American troops in 1898. Their arrival was followed by the outbreak of the Philippine-American War in 1899 as the colonial intentions of the USA became clear. In the same year, Filipino revolutionaries promulgated the Malolos Constitution, outlining in detail the political and administrative system for the new government, even as the war raged (Abueva1988). These never fully materialized as most of the Philippine revolutionary forces either fell or surrendered to the Americans by 1902, even as small pockets of resistance remained.

The foundations of the modern-day political and administrative systems of the Philippines were established under the direction of the USA from 1898 to 1946. The USA initially established a colonialmilitary government followed by the civilian Insular Government of the Philippine Islands. In contrast to Spain, Americans established a secular government with republican and democratic characteristics, established a public educational system, and allowed increased political participation of Filipinos. Emerging ideas about the “science of administration” influenced their establishment of a professional civil service influenced by merit principles. Additionally, there was a very strong drive for the American colonial government to replace the graft-ridden Spanish civil service with one that is professional and selected based on merit (Reyes2011). The Commonwealth of the Philippines was established under Filipino political leaders in the presidential elections of 1935, following passage of the Philippine Independence Act of 1934. The Commonwealth was intended to be a transition government in preparation for eventual independence (Hutchcroft2000; Karnow1989; Reyes2011).

Preparation for Philippine independence was interrupted by the outbreak of World War II in 1941 and occupation by the Japanese Imperial Army from 1942 to 1945. In place of the Commonwealth government, whose leaders fled the country with American forces, Japan installed a puppet government with conscripted Filipino leaders under the command of the occupying forces. This period was marked by disruption in the political, economic, and social life as well as in the bureaucracy (Reyes2011). Filipinos occupying administrative positions were torn between trying to maintain government services and covertly supporting resistance forces fighting Japan. Supporters of Japan were branded as traitors and collaborators. Scholars note that it was common then for bureaucrats to engage in acts of corruption and deliberate sabotage, partially as a form of resistance and an expression of nationalism (Corpuz1957). Japan’s occupation ended when the USA reclaimed the Philippines in the 1945 Battle of Manila.

The period after 1945 involved massive rebuilding of both infrastructure and the political and administrative systems destroyed during the war. Manila, the capital, is often cited as the second most devastated city in the world during World War II after Warsaw, Poland. Most of the destruction attributed to carpet bombing by American forces against Japanese Imperial forces. The war destroyed infrastructure, killed a substantial part of the population, and left the economy and the bureaucracy in shambles. On the 4th of July 1946, the USA granted independence to the Philippines while the country was still struggling to recover from the destruction of the war. New leaders were elected, and rehabilitation and rebuilding began. Many bureaucrats who served under the Japanese were ostracized as collaborators (Corpuz1957). The civil service was weakened, traumatized, and lost much of its previous prestige (Reyes2003).

In 1950, the Bell Mission was sent to assess the situation of the Philippines. Part of the mission involved assessing political and administrative capability. The mission concluded that “only the most far-reaching program of reform and self-help, supported by economic and technical assistance from this country [United States] could save the Philippines from total collapse” (Eggan1951, 16). To rebuild the bureaucracy, and consistent with the mission’s recommendations, the Institute of Public Administration (IPA) was established on June 15, 1952, at the University of the Philippines. Its mission was to provide training, teaching, and research in public administration. Filipinos were sent to the USA and trained in American government and public administration. Gradually, the bureaucracy was rebuilt in line with the structures, systems, and principles of American public administration as the country recovered (Reyes2011).

Before World War II, civil servants in the Philippines enjoyed job security, competitive wages, attractive hours, and generous benefits under the American regime (Endriga2003). The civil service was a prestigious career. Political events during and after World War II led to economic hardship and a general distrust toward the government. Rampant corruption and graft in the 1950s and 1960s, along with the declaration of Martial Law under the Marcos Regime, took away the prestige and privileges associated with the civil service (Reyes2011).

While he was elected democratically in 1965 to a four-year term and reelected in 1969 for a second four-year term, Ferdinand Marcos’ declaration of Martial Law from 1972 to 1981 established an authoritarian government. It stayed in power until it was ousted by the People Power Revolution of 1986. Marcos controlled the armed forces, centralized both executive and legislative powers under the Presidency, and effectively ruled by decree. The judiciary was weakened, mass media were largely controlled by the regime, the opposition was restrained, and protests and dissent were suppressed by the authorities, often violently (Thompson1995).

In this period, many private enterprises were nationalized or transferred to accomplices of the regime (Celoza1997). Internally, the bureaucracy also experienced conflicting directions. On the one hand, Marcos initiated efforts to reorganize, professionalize, rid the civil service of unqualified personnel, and codify a new civil service code. On the other hand, tenured members of the civil service were summarily dismissed and replaced by accomplices of the regime. The civil service became both a “willing and unwilling” collaborator of the regime (Reyes2011, 348). Graft and corruption at the highest levels became rampant under the Marcos regime. The economy also spiraled downward, and the Philippines was buried in debt. By 1986, Philippine debt had ballooned from only $600 million in 1965 when Marcos was first elected to $26 billion.

Marcos was ousted in the People Power Revolution of 1986. The new President, Corazon C. Aquino, initially established a Revolutionary Government in 1986 and then a new government under a new Philippine Constitution in 1987. The separation between the executive, legislative, and judiciary was restored, and safeguards were adopted with the intention of preventing the abuses that had happened under the Marcos regime. The period was also marked by the new regimes’ attempt to reorganize, rationalize, and cleanse the government of the vestiges of Marcos. The job security of civil servants was once again challenged with the removal of tenured personnel as the new regime attempted to “de-Marcosify” the government. New people were appointed in political and administrative positions and a new code of conduct and ethical standards for public officials and employees were passed. The new regime sought to reinvigorate the civil service and undo the legacies of the Marcosregime (Cariño1989; Reyes2011, 349).

After 1986, the bureaucracy was characterized by a period of relative normalcy. A major change in the civil service came in 1992 when the Philippines adopted the Local Government Code of 1991 and the national government embarked on a process of deconcentrating, decentralizing, and devolving many of its powers and functions to local government units. Instead of the previous system of appointments, elections were restored at the local level. Local government units—provinces, cities, municipalities, and barangays—were established to serve both political and administrative functions. These enjoyed a measure of autonomy from the national government. Personnel from national agencies were devolved to, and absorbed by, local government units (Brillantesand Sonco2011).

The post-1987 period in the Philippines also followed developments in political and administrative thought in the West, albeit with some delay. Reinventing Government, New Public Management, and associated ideas shaped much of the administrative policies adopted by the Philippine government. The government embarked on privatization of public enterprises, outsourced and contracted services, adopted performance management systems, and even adopted e-government. Succeeding administrations carried forward these public-sector reform programs. For example, during the presidency of Fidel V. Ramos (1992–1998), the bureaucracy was reengineered with the goal of achieving better governance. During the rule of Joseph Estrada (1998–2001), effective governance was emphasized. Gloria Macapagal Arroyo’s administration engaged in the streamlining of the bureaucracy (Domingoand Reyes2011). In 2012, the administration of President Benigno Simeon Aquino Jr. also adopted a results-based approach toward performance management. It was called the Strategic Performance Management System (SPMS) and was accompanied by a Performance-Based Incentive System (PBIS) to rationalize the bonuses granted to public sector personnel (Torneo et al. 2017a, b).

Dimensions of National Culture and the Philippine Bureaucracy

The history, experiences, and development of Philippine public administration have allowed it to develop a culture that varies somewhat from the broader societal culture. Reyes (2011) argues that public administration in the Philippines observes and pursues administrative values that are a mixture of three major sometimes compatible, sometimes conflicting, influences. He enumerates these influences as: the wider Filipino societal culture, the norms of Weberian bureaucracy, and the influences of the colonial periods. These result in a civil service that is in many ways similar in form to the USA after which it was patterned, but with a distinct character and unique set of challenges particular to its culture and context.

Based on his intensive study of how workers’ values are shaped by national culture, Geert Hofstede (1984) argued that national cultures could be grouped into four dimensions: power distance, individualism, masculinity, and uncertainty avoidance. These four perspectives came to be known as Hofstede’s Dimensions of National Culture. These dimensions have since increased to include long-term orientation and indulgence, bringing the total to six dimensions. These provide a better understanding of the values, beliefs, and norms of a country as well as its workers’ values. They can also help put the workings of a country’s civil service into context.

The power distance index describes how workers from lower ranks accept that power is distributed unequally throughout an organization. Individualism classifies societies into individualistand collectivist societies. People in collectivist societies tend to gravitate toward each other and are taught at an early age that both immediate and extended family ties are very important. Individualistic societies, on the other hand, tend to be independent of one another, and they focus on taking care of themselves and their immediate family (Hofstede1984).

Masculinity describes the extent to which a country values achievement and success as compared to valuing nurturing behaviors and equality. Masculine countries tend to strive for achievement and gains in material wealth. Feminine countries are more concerned with quality of life rather than personal gain. Uncertainty avoidance, on the other hand, is the extent to which societies try to deal with the unknown. Countries with high uncertainty avoidance would be more likely to enforce strict laws and behavioral codes in order to minimize uncertainty. Those that score low on uncertainty imposes fewer restrictions are more lenient with laws and their enforcement, and they tend to believe more in change and innovation (Hofstede1984).

Based on Hofstede’s (n.d.-a) dimensions of national culture, the Philippines scores 94/100 in the power distance index, which exemplifies its hierarchical social structure and the people’s acceptance of the culture of dualism that is pervasive throughout society. The hierarchical nature of Philippine society, while not as pronounced as in Confucian Asian societies, does have overt manifestations that link to social, political, and economic factors. Children are taught from a young age to respect their elders. Both children and adults perform an honoring gesture called “mano” with elder family, kin, or family friends. Filipino language also adds the polite modifier “po” or “opo” at the end of sentences to signify respect to elders, people perceived to be of high standing, superiors within an organization, religious authority, and even strangers.

In the context of the civil service, hierarchy may be observed in the prevalence of top-down decision-making in public organizations. Unlike in more egalitarian cultures, Filipino employees look up to, and defer to, their superiors and people in authority. They have come to expect that those in higher positions enjoy privileges that may go beyond those that are accorded to their own positions. This phenomenon is called dualism and is a manifestation of the unequal power distribution prevalent in Philippine society.

Varela (2003) argues that dualism has been alive in the islands even before Spanish colonization. Reyes (2003) argues that dualism was further ingrained in Filipino culture during the Spanish and American regime. Under Spain, the caste system was largely erased, and the status of natives was relegated to below the Spanish and Spanish mestizos. Then came the Americans, who looked down on Filipinos as “little brown brothers” who needed to be civilized (Wolff1961). In more recent history, dualism manifests in the better treatment accorded to those in the higher levels of society relative to those in lower positions. Elite officials who are found to be involved in corrupt practices or scandals are often exonerated by presidents while lower-ranking employees suffer more severe consequences. According to Varela (2003), “… these cases of bureaucratic dualism are replicas of the double standard in society covering all aspects of life: familial, social, political, economic, and even religious” (463).

The Philippines scores 32 out of 100 in the individualism dimension. This indicates that it is a collectivist society. This dimension is exemplified by three major traits that Jocano (1981) argues, greatly influences Filipino behavior and decision-making: personalism, familism, and particularism or popularism. Personalism refers to the value Filipinos place in interpersonal communication. Familism refers to the importance, in terms of welfare and interest, given to family over the community. Lastly, particularism or popularism refers to the importance of being well-liked and widely accepted by a group, a community, or an organization. Cultural values such as utang-na-loob (related to debt of gratitude), and pakikisama (related to maintaining camaraderie) are held in high regard.

These traits can be seen both positively and negatively, depending on the context. On the one hand, they contribute to the smooth interpersonal relations of Filipinos, who can get along with others without showing signs of conflict. They emphasize “being agreeable even under difficult circumstances, sensitive to what others are feeling, and willing to adjust one’s behaviour accordingly” (Jocano1973, 274). On the negative side, it can also contribute to the unwillingness of civil servants to engage in confrontation or outright conflict and instead may result in compromising policies and procedures to avoid disagreements or differences (Reyes2011, 349). It can also contribute to nepotism and patronage within the bureaucracy (Varela2003).

The culture of patronage is influenced by the values, beliefs, and norms associated with familism, utang-na-loob, pakikisama, nepotism, and favoritism (Varela2003). Reyes (2003) notes that the policies and practices of filling public offices during Spanish colonization were conceivably the start of the culture of patronage within the Philippine civil service. The practice has become so ingrained within the Philippine culture that it has developed into a societal and administrative norm. De Guzman (2003, 6) best describes the acceptance of this norm within the bureaucracy this way: “Administrators generally accept civil service eligibility as a minimum requirement, but between two or three civil service eligible, they could then choose the one recommended by a politician, a compadre, or a relative.”

The Philippines scores 64 out of 100 on the masculinity dimension, making it a masculine country in Hofstede’s typology. This denotes a strong value for achievement and gain of material wealth. This is exemplified in economic migration as an accepted way of life in the Philippines. Altogether, almost 10.2 million people of Filipino descent are working and living overseas with many living as permanent residents or having citizenship in other countries. Officially, 2.3 million Filipinos work as Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) or migrant workers overseas, primarily in order to improve the lives of their families. These numbers do not take into account the rural to urban migrants or the workers that leave their family in the province to find jobs in the cities. Varela (2003) also notes that most Filipino rank and file employees work multiple jobs or have multiple sources of income to provide for their family.

The strong value for achievement and material wealth may be further reinforced by the link between economic standing and social status. While the Philippines does not have a formal caste system in place, there are high levels of economic inequality and poverty. Those with higher economic status enjoy higher social standing. At the top of the hierarchy are a handful of elite families who hold both economic and political positions at the national and local levels (McCoy2009). Well-to-do families still typically employ maids from poorer families to do household and menial chores. Because economic mobility is associated with social status, many parents strive and sacrifice to provide their children a good education to improve their socio-economic position and, in the hope, that it will help them lift their families out of poverty.

The Philippines scores 44 out of 100 in the uncertainty avoidance dimension. This reflects the low preference for avoiding uncertainty, a relaxed attitude in which practice counts more than principles, and deviation from rules is tolerated. The Philippines has numerous laws to address graft and corruption, which include, among others, the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act, the Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees, and the Procurement Reform Act. Despite these laws, anti-corruption measures have shown little success and very few high-level officials have been convicted for graft and corruption.

Despite promises of reforms, 2017 data from Transparency International show that the Philippines still ranks 111th out of 180 countries in the Corruption Perceptions Index. Varela (2003) argues that a lot of the laws, orders, and decisions conflict with each other, which renders transparency within the system difficult. The challenge of navigating the legal jungle has led to increased ambiguity and acceptance of uncertainty. Furthermore, laws are often not strictly enforced, and implementation is uneven and sometimes follows a case-by-case basis.

The Survey

In this section, we report the data analysis of the survey on emotional labor conducted among public sector employees in the Philippines. The survey was conducted in Pasay City during August and September 2015. Pasay City is located in Metropolitan Manila, the National Capital Region of the Philippines. The city’s total population was 417,000 in 2015. We contacted the Pasay City government personnel office, distributed, and recovered 252 survey questionnaires to city employees. Of the total questionnaires, we obtained 209 usable responses, which yielded an 81.7% response rate. Table 15.2 summarizes demographic characteristics of the respondents. A majority, approximately 63%, are in their 40s and 50s. There are more female respondents (60%) than male respondents. In terms of the education level, most of the respondents (87.5%) are college graduates or higher.

The respondents are from various occupations (see Table 15.3). The top five occupations claim about half of the total occupations (52.7%). In descending order, they are health care (16.1%), administration (12.2%), finance or accounting (8.9%), community development/ neighborhood services (8.0%), and education (7.5%).

This study employs structural equation modeling (SEM) to investigate the effect of emotional labor on behavioral outcome variables. Emotional labor in this study is composed of three dimensions (Yang et al. 2018). The three constructs of emotional labor are emotive capacity, pretending expression, and deep acting. The three behavioral variables included in the model are job satisfaction, burnout, and personal fulfillment. Table 15.4 summarizes the mean scores, standard deviations, and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. In terms of the reliability test, all of the variables achieve a Cronbach’s alpha level of above 0.7.

Table 15.5 summarizes the results of the structural equation modeling analysis.

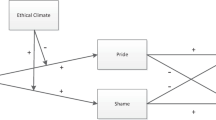

Figure 15.1 depicts a path diagram showing relationships between the emotional labor variables and the behavioral variables. The bold paths are statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05. As shown, the emotive capacity variable has a significant effect on the three behavioral variables. It is positively related to both job satisfaction and personal fulfillment, while it is negatively related to burnout. In the Philippine context, as workers perceive that they are good at dealing with emotional issues in their workplace, they are more likely to be satisfied with their job. Likewise, the more an employee feels a high level of emotive capacity, the higher the level of his or her personal fulfillment is. As well, high emotive capacity diminishes the likelihood of burnout.

In terms of the effect of pretending expression, this variable shows no significant effect on job satisfaction, burnout, or personal fulfillment. Traditionally, analysts believe that suppressing individual’s true feelings to appear pleasant in a workplace causes burnout as well as decreases job satisfaction and personal fulfillment (Hochschild1983; Morrisand Feldman1996). However, this is not true in the case of the Philippines. It seems the intensity of emotive pretending, whether it is high or low, does not lead to any meaningful difference in job-related behavior for Philippine public sector employees. The idea that emotive pretending has a negative effect was primarily developed in the US work environment. The finding from the Philippine data implies that emotive pretending is experienced differently in this culture and context.

The results also reveal that deep acting has a statistically significant positive impact on burnout. The direction of the relationship between deep acting and burnout is not consistent with findings in the US. Hochschild (1983) posits that deep acting among US workers can lessen burnout while strengthening job satisfaction and personal fulfillment. The Philippine survey shows a different result, with authentic emotive expression increasing, rather than decreasing, burnout. This leads to the question of whether there are cultural differences in emotive expression that are specific to the Philippines (Matsumotoand Yoo2008).

Discussion of Results

It is possible that the differences in the impact of emotional labor in the Philippines and the USA may partially reflect differences in culture and context. Using the latest data on Hofstede’s dimensions of national culture, we find that the two countries have similar scores in the masculinity and uncertainty avoidance dimensions, but they differ in the power distance and individualismdimensions (HofstedeInsights n.d.-a, n.d.-b). The Philippines is a highly collectivist society with a score of 32 in the individualism dimension whereas the USA is a highly individualist society with its score of 91. The Philippines tends to be more accepting of hierarchy with its score of 94 in the power distance index while the USA is more egalitarian with a score of 40. In the masculinity dimension, the Philippines scored 62 and the USA scored 64, indicating the strong value the culture in both countries place on material well-being. In the uncertainty avoidance dimension, the Philippines scored 44 while the USA scored 46, suggesting both cultures have a relaxed attitude toward rules and regulations and that deviating from the rules is tolerated.

We do not have enough data at this point to definitively resolve how much of the differences in the Philippine and the US cases can be explained by cultural or contextual differences. We note that among the countries covered in the study reported in this handbook, the effect of emotional labor on behavioral outcome variables in the Philippines is most similar to Thailand and India. It is identical to Thailand and differs with India on only one relationship. While there is a significant positive relationship between deep acting and burnout in the Philippines, there is no relationship between these two variables in India. Why this is the case requires further exploration, especially since these three countries have very distinct cultures and public administration traditions.

Interestingly, the results also reveal that the impact of some dimensions of emotional labor in the Philippines also differs between public and private sector employees. The impact of deep acting on burnout among the government employees surveyed in this study is different from its impact on those in the private sector in previous studies. Barcebal et al. (2010) found that surface acting, but not deep acting, is related to exhaustion and burnout among employees of service organizations. These employees tended to engage in more deep acting rather than surface acting, but this did not correlate significantly with exhaustion and burnout. Newnham (2017), on the other hand, found that Filipino hotel frontline service workers report higher levels of burnout when using surface acting and lower levels of burnout when using deep acting more often.

The difference in the impact of surface and deep acting between Philippine public and private organizations merits further investigation. It may reflect differences in methodology and measurement between the studies, differences in the organizations where the surveys were conducted, or even fundamental differences in the culture and context of Philippine private sector and public sector organizations. It is difficult to resolve this question without a deeper study, but preliminary information provides some leads worth investigating.

As noted earlier, government employees in the Philippines operate in an environment where values are a mixture of three sometimes compatible, sometimes conflicting, influences. These include the broader Filipino societal culture with its idiosyncrasies which include personalism, familism, and debt of gratitude among others; the formalities dictated under the norms of Weberian bureaucracy, which include strict adherence to rules; and colonial influences, which include merit and fitness among others (Reyes2011, 349).

The mixture of values means that Filipino government employees must navigate their mandates along with a complex set of cultural expectations that may vary from case to case and from time to time. These can conceivably take a toll in terms of job satisfaction, personal fulfillment, and burnout. An employee might take on the role of an impersonal and strict rule-abiding civil servant when dealing with the general public one moment and then switch into a more sympathetic, personalistic, and flexible persona when dealing with “very important persons” (VIPs), friends, or relatives the next moment. The latter may also have to deal with requests for favors which on occasion may entail deviating from established policies and procedures which is likely to be stressful. This is likely to occur in local governments since employees will generally be dealing with people from their own communities.

Another factor to consider is that Filipino government employees are expected to meet public expectations in an environment of scarce resources and low pay. When the survey was conducted, the average pay of Philippine government employees was generally lower than their private sector counterparts. In the local setting, government employees must deal with all kinds of requests ranging from routine public services to sometimes desperate pleas for assistance for hospitalization, medicine, scholarships, weddings, jobs, and even burials. Expectations are from womb to tomb. The resources of local governments, however, are often very limited. Even when employees sincerely want to extend help, they may not always have enough resources or the best means to do so. Plausibly, this requires significant emotional labor on their part.

Lastly, Philippine government employees often have to deal with political pressure and navigate the sometimes-turbulent waters between politics and administration. In addition to complying with legal and administrative rules, they also must be sensitive to the expectations of political principals. This is especially true in local governments since the distance between elected officials and their constituents tend to be very narrow. A local government employee must be highly sensitive to political cues. For example, they cannot simply just invoke the rules and turn away “special requests.” They must be careful lest they offend supporters, friends, or relatives of incumbent local officials and affect their chances for reelection.

Private sector employees in the Philippines generally do not have to navigate the same set of complex rules and expectations as public sector employees. Overall, they tend to have narrower and better-defined performance targets, enjoy better pay, serve only a select group of clienteles, and are able to treat all clients in a similar manner: as customers whose business is important and whose satisfaction is of paramount importance. They do not have to switch roles as often, do not have to deal with political pressure and political principals, have a limited set of public expectations, and are less likely to deal with situations involving breaking with established rules or procedures when compared to local government employees.

We end this chapter with the proposition that the effect of emotional labor on behavioral outcome variables including job satisfaction, personal fulfillment, and burnout in the Philippine public sector may be tempered by cultural and contextual factors whose mechanisms we do not yet fully understand, and which should be subject to further study. Culture and context may potentially explain the similarities in the findings between the Philippines, Thailand, and India, the notable differences in the USA and Philippines, and the differences in the emotional labor between Philippine private and public sector employees. Future studies should consider integrating measurable social and cultural dimensions in the empirical model and complement this with comparative or cross-case analysis to gauge how these dimensions relate to aspects of emotional labor between and within country cases. Mixed methods research can also probe more deeply the particularities, the context, and the relationship among the various dimensions of emotional labor in the context of Philippine public and private sector organizations.

References

Abueva, J. V. 1988. “Philippine Ideologies and National Development.” In Government and Politics of the Philippines, edited by Raul P. de Guzman and M. A. Reforma, 8–73. Singapore: Oxford University Press.

Barcebal, M., M. Chua, K. A. Dulay, and G. Hechanova. 2010. “Emotional Labor and Burnout Among Filipino Service Workers.” Philippine Daily Inquirer, June 21. Retrieved from https://www.pressreader.com/philippines/philippine-daily-inquirer/20100621/283631051282797.

Brillantes, A., and J. T. Sonco. 2011. “Decentralization and Local Governance in the Philippines.” In Public Administration in Southeast Asia: Thailand, Philippines, Malaysia, Hong Kong, and Macao, edited by Evan M. Berman, 355–79. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press.

Cariño, L. V. 1989. “Bureaucracy for a Democracy: The Struggle of the Philippine Political Leadership and the Civil Service in the Post-Marcos Period.” Philippine Journal of Public Administration 33 (3): 2017–252.

Celoza, A. F. 1997. Ferdinand Marcos and the Philippines: The Political Economy of Authoritarianism. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Publishing Group.

Civil Service Commission. 2017. Inventory of Government Human Resource (as of August 31, 2017). Retrieved from http://www.csc.gov.ph/phocadownload/IGHR/2017/IGHR%20Manual%20FY2017_asofAugust31.pdf.

Corpuz, Onofre D. 1957. The Bureaucracy in the Philippines. Manila, Philippines: Institute of Public Administration.

De Guzman, Raul P. 2003. “Is There a Philippine Public Administration?” In Introduction to Public Administration in the Philippines: A Reader. 2nd ed., edited by V. A. Bautista, M. P. Alfiler, D. R. Reyes, and P. D. Tapales, 3–11. Quezon City, Philippines: National College of Public Administration and Governance.

De la Torre, Visitacion R. 1986. History of the Philippine Civil Service. Quezon City, Philippines: New Day Publishers.

Domingo, M. O. Z., and D. R. Reyes. 2011. “Performance Management Reforms in the Philippines.” Public Administration in Southeast Asia: Thailand, Philippines, Malaysia, Hong Kong, and Macao, edited by Evan M. Berman, 397–402. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Eggan, F. 1951. “The Philippines and the Bell Report.” Human Organization 10 (1): 16–21.

Endriga, J. N. 2003. “Stability and Change: The Civil Service in the Philippines.” In Introduction to Public Administration in the Philippines: A Reader. 2nd ed., edited by V. A. Bautista, M. P. Alfiler, D. R. Reyes, and P. D. Tapales, 393–414. Quezon City, Philippines: National College of Public Administration and Governance.

Guy, Mary E., Meredith A. Newman, and Sharon H. Mastracci. 2008. Emotional Labor: Putting the Service in Public Service. Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe.

Hochschild, Arlie. 1983. The Managed Heart. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Hodder, R. 2009. “Political Interference in the Philippine Civil Service.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 27 (5): 766–82.

Hofstede, Geert. 1984. “Cultural Dimensions in Management and Planning.” Asia Pacific Journal of Management 1 (2): 81–99.

Hofstede Insights. n.d.-a. Philippines. Accessed April 13, 2019. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country/the-philippines/.

Hofstede Insights. n.d.-b. United States. Accessed April 13, 2019. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country/the-usa/.

Hutchcroft, P. D. 2000. “Colonial Masters, National Politicos, and Provincial Lords: Central Authority and Local Autonomy in the American Philippines, 1900–1913.” The Journal of Asian Studies 59 (2): 277–306.

Jocano, F. Landa. 1973. Folk Medicine in a Philippine Community. Quezon City, Philippines: Punlad Research House.

Jocano, F. Landa. 1981. Folk Christianity: A Preliminary Study of Conversion and Patterning of Christian Experience in the Philippines. Quezon City, Philippines: Trinity Research Institute, Trinity College of Quezon City.

Karnow, S. 1989. In Our Image: America’s Empire in the Philippines—Headlines Series 288. New York, NY: Foreign Policy Association.

Matsumoto, D., and S. H. Yoo. 2008. “Methodological Considerations in the Study of Emotion Across Cultures.” In Handbook of Emotion Elicitation and Assessment, edited by J. A. Coan and J. J. B. Allen, 332–48. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

McCoy, A. W., ed. 2009. An Anarchy of Families: State and Family in the Philippines. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Morris, J. A., and D. C. Feldman. 1996. “The Dimensions, Antecedents, and Consequences of Emotional Labor.” Academy of Management Review 21: 986–1010.

Newnham, M. P. 2017. “A Comparison of the Enactment and Consequences of Emotional Labor Between Frontline Hotel Workers in Two Contrasting Societal Cultures.” Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism 16 (2): 192–214.

Reyes, D. R. 2003. “Public Administration in the Philippines: History, Heritage, Hubris.” In Introduction to Public Administration in the Philippines: A Reader. 2nd ed., edited by V. A. Bautista, M. P. Alfiler, D. R. Reyes, and P. D. Tapales, 38–65. Quezon City, Philippines: National College of Public Administration and Governance.

Reyes, D. R. 2011. “History and Context of the Development of Public Administration in the Philippines.” In Public Administration in Southeast Asia: Thailand, Philippines, Malaysia, Hong Kong, and Macao, edited by Evan M. Berman, 355–80. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Ruppel, C. P., R. L. Sims, and P. Zeidler. 2013. “Emotional Labour and its Outcomes: A Study of a Philippine Call Centre.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration 5 (3): 246–61.

Sia, L. A. 2016. “Emotional Labor and Its Influence on Employees’ Work and Personal Life in a Philippine Franchise Dining Industry Setting.” International Journal of Applied Industrial Engineering (IJAIE) 3 (1): 74–85.

Thompson, M. R. 1995. The Anti-Marcos Struggle: Personalistic Rule and Democratic Transition in the Philippines. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Torneo, Ador R., Georgeline B. Jaca, Jose Ma Arcadio C. Malbarosa, and Jose Lloyd D. Espiritu. 2017a. Impact of the PBIS on the Productivity and Morale of Employees of the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG): A Quantitative Assessment. Unpublished Report Submitted to Philippines-Australia Human Resources and Organisational Development Facility (PAHRODF).

Torneo, Ador R., Georgeline B. Jaca, Jose Ma Arcadio C. Malbarosa, Jose Lloyd D. Espiritu. 2017b. Preliminary Assessment of the Performance-Based Incentives System (PBIS) on Selected Agencies: Policy Recommendations. Accessed March 2, 2019. https://www.pahrodf.org.ph/prgs/final-policy-notes/pbis-policy-note-final.pdf.

Varela, A. 2003. “The Culture Perspective in Organization Theory: Relevance to Philippine Public Administration.” In Introduction to Public Administration in the Philippines: A Reader, 2nd ed., edited by V. A. Bautista, M. P. Alfiler, D. R. Reyes, and P. D. Tapales, 438–72. Quezon City, Philippines: National College of Public Administration and Governance.

Wharton, Amy S. 2009. “The Sociology of Emotional Labor.” Annual Review of Sociology 35: 147–65.

Wolff, L. 1961. Little Brown Brother: How the United States Purchased and Pacified the Philippine Islands at the Century’s Turn. Quezon City, Philippines: Wolff Productions.

Yang, Seung-Bum, Mary E. Guy, Aisha Azhar, Chih-Wei Hsieh, Hyun Jung Lee, Xiaojun Lu, and Sharon H. Mastracci. 2018. “Comparing Apples and Manzanas: Instrument Development for Cross-National Analysis of Emotional Labor in Public Service Jobs.” International Journal of Work Organization and Emotion 9 (3): 264–82. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJWOE.2018.10015953.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Torneo, A.R. (2019). Philippines. In: Guy, M.E., Mastracci, S.H., Yang, SB. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Global Perspectives on Emotional Labor in Public Service. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-24823-9_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-24823-9_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-24822-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-24823-9

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)