Abstract

Current food systems are in need of profound changes. The number of hungry people recently rose to over 820 million due to climate-related conflicts and displacement. Two billion people in the world are overweight or obese and are at risk of the diseases related to over-consumption of food, an issue that affects both the developed and developing world. The food sector operates—and depends on—a natural environment profoundly under stress and faces increasing competition for its resources between different sectors. Food is the largest freshwater user, accounts for one third of GhG emissions and is responsible for land degradation, biodiversity loss and pollution. Sustainable food systems are at the core of the 2030 Agenda of the United Nations, signed by 193 countries in 2015, as food is directly or indirectly connected to all the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Against this context, the present chapter outlines the main challenges that the global food system currently faces in terms of nutrition challenges, environmental impacts and food loss and waste, with each of these dimensions put into relation with the relevant SDGs, underlining the importance of sustainable food systems for implementing the 2030 Agenda.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Current food systems are in need of profound changes as they still fail to provide basic food requirements for a large share the world’s population while being responsible for an unsustainable burden on the environment. The world population is expected to reach ten billion by 2050, with a projected increase in food demand by 50% compared to 2013, also driven by the dietary transition that especially low- and middle-income countries are experiencing (FAO 2017). Unless we radically transform food systems, additional food demands will drive, in the future, an increase in GHG (Greenhouse Gas) emissions, land and water use, as well as trigger conflicts, social unrest and migrations (FAO 2017).

The number of hungry people, for the second year in a row, has continued to increase up to over 820 million (FAO 2018a, b, c), while two billion people are overweight or obese (World Health Organization (WHO) 2018b). Nearly one third of food production is lost or wasted, respectively before reaching the market or at the end-user level (Gustavsson et al. 2011). The food sector also operates—and depends on—a natural environment profoundly under stress and faces increasing competition for natural resources between different sectors. Crop production is the largest freshwater user (about 70% of withdrawal on a global average), accounts for about 12% of the globe’s land surface (arable land and land under permanent crops), and is responsible for land degradation, biodiversity loss and pollution of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems (FAO AQUASTAT 2019; Alexandratos and Bruisma 2012). Climate change is both impacted by food systems and has an impact on food systems. A large share of GHG emissions, ranging from 18% and 51%, has been linked to food supply chains (Steinfeld 2006; Goodland and Anhang 2009). At the same time, climate change may decrease food availability by jeopardizing crop and livestock production, fish stocks and fisheries, while increasing food price volatility (FAO 2017, 2018a). These changes will affect disproportionately developing countries and the poorest populations.

Acting as a multiplier of the already existing competition over land and water resources, biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation, food crises and malnutrition, population displacement and migrations, conflicts and social unrest, climate change is considered “the defining issue of our time”.Footnote 1 Since 2011, climate-related risks such as water crises, flooding, biodiversity loss, greenhouse gas emissions, are placed among the top 5 global risks both in terms of likelihood and impact by the World Economic Forum (2019). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC 2018) has emphasized that climate change will impact all aspects of food security and that “rapid, fair-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society” are necessary to keep global warming below 1.5 °C, relative to pre-industrial levels. The Paris Agreement, although not mentioning explicitly agriculture, has the potential to unlock opportunities for transforming food and farming systems, to safeguard food security, address vulnerabilities of food supply chains, guarantee human rights and the health of ecosystems and biodiversity.

Sustainable food systems are at the core of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development defined by the United Nations and signed by 193 countries in September 2015, to build peace, prosperity and inclusiveness in the world, and enable “socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable economic growth” (Sachs 2015, p. 3). While the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 pledges to eradicate hunger and malnutrition, food and food systems are directly or indirectly connected to all 17 SDGs (FAO 2018b), as key enabling factors or as main targets to be achieved.

Against this context, the present chapter outlines the main challenges that the global food system currently faces in terms of nutrition challenges (Sect. 2), environmental challenges (Sect. 3), food loss and waste (Sect. 4). Each of these dimensions will be put into relation with the relevant SDGs. Finally, the chapter provides a few recommendations on how to bring about a transformational change towards sustainable and healthy food systems with the contribution and cooperation of all stakeholders—from policy-makers, to business, citizens and civil society organizations.

2 Nutrition Challenges

Food systems today are posed with the unprecedented challenge of feeding an increasingly growing and urbanized population and are currently falling short in meeting nutritional requirements and guaranteeing long term health for almost half of people worldwide (Global Nutrition Report 2017).

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the total world population crossed the threshold of one billion for the first time in the history of the homo sapiens sapiens. Since then, growth rates have been increasing exponentially, reaching remarkably high peaks in the twentieth century, when the total world population reached seven billion just after 2010 (Van Bavel 2013) and is expected to count ten billion by 2050 (FAO 2017). This growth goes hand in hand with global urbanization: in 1950, 30% of the world’s population was urban, and by 2050, 66% of the world’s population is projected to be urban (UN 2014). It is widely upheld that urbanization affects nutrition patterns, as changing environment and preferences is a driver of a change in diet. City dwellers generally consume more animal-source foods, sugar, fats and oils, refined grains, and processed foods, with urban food systems currently accelerating the nutrition transition. On the one hand, urban environments facilitate access to unhealthy diets (i.e. greater availability of fats and sugars), on the other they can improve access to nutritious foods for the wealthier segments of population (Hawkes et al. 2017). For this reason, national policies addressing food environments are particularly relevant to municipalities.

Despite the significant gains in improving the global nutritional status, still there is almost no country immune from a significant nutrition challenge, with many countries facing a double, if not triple burden of malnutrition, where undernutrition coexists with overweight and obesity within the same country, the same community and even the same household (WHO 2016).

In 2017, the number of undernourished people rose to 821 million people, up from 804 million in 2016, with Instability in conflict-ridden regions, adverse climate events and economic slowdowns explaining this deteriorating situation (FAO 2018a, b, c). Globally in 2017, 151 million children under the age of 5 were stunted, i.e. too short for their age, and 51 million children under the age of 5 were wasted, i.e. too light for their height. Stunting is the result of chronic malnutrition and affects mainly children living in Asia-Pacific and Africa regions (WHO 2018a). At the same time, two billion people lack key micronutrients (Global Nutrition Report 2017) with iron, iodine, folate, vitamin A, and zinc deficiencies being the most widespread micronutrient deficiencies (MNDs) (Bailey et al. 2015). Low- and middle-income countries have the highest burden of MNDs as the main cause of undernutrition is poverty. However, underestimated MNDs, so-called “hidden hunger”, pose health risks in developed economy settings as well. In this alarming scenario, some countries, such as Brazil, are taking action. Stunting prevalence among children younger than 5 years in the country decreased from 37% in 1974–1975 to 7% in 2006–2007 thanks to rapid advances in economic development and healthcare, and interventions outside the health sector, including a conditional cash transfer program and improvements in water and sanitation (Keefe 2016; Victora et al. 2011).

Meanwhile, worldwide obesity has nearly tripled since 1975. In 2016, almost two billion adults are overweight, and 650 millions of these were obese. On a global level, this translates into 39% of adults aged 18 years and over being overweight in 2016, and 13% obese (WHO 2018a). In parallel, the world has seen a more than tenfold increase in the number of obese children and adolescents aged 5–19 years in the past four decades, rising from just 11 million in 1975 to 124 million in 2016. An additional 213 million were overweight in 2016 but fell below the threshold for obesity. Taken together this means that in 2016 almost 340 million children and adolescents aged 5–19 years, that is almost one in every five (18.4%) were overweight or obese globally (Global Nutrition Report 2017). The data confirms the alarming prevalence of overweight and obesity, both among adults and children, in a number of countries. In Saudi Arabia, for example, 69.7% of adults have a BMI over 25. A similar trend applies to Jordan (69.6% of overweight and obese adults), the United States and Lebanon (67.9%) (WHO 2016).

Overweight and obesity cannot be considered as a mere result from the subtraction “ingested foods - caloric expenditure” but are rather very complex conditions. Certainly, individual choices such as poor diets, physical inactivity and sedentary behavior play their part, but interact with multiple social, economic and environmental factors. Scientific evidence brings out the significant role of the “obesogenic environment”, defined as ‘the sum of influences that the surroundings, opportunities, or conditions of life have on promoting obesity in individuals or populations’ (Swinburn and Egger 2002). According to the Global Nutrition Report published in 2017, “No country has been able to stop the rise in obesity”, and countries with burgeoning prevalence should start early to avoid some of the mistakes of high-income neighbors.

Furthermore, the double burden of malnutrition is a growing global challenge and is characterized by the coexistence of undernutrition along with overweight, obesity or diet-related NCDs, on different levels: individual, household and population, and across the life-course (WHO 2016). The simultaneous increases in obesity in almost all countries seem to be driven mainly by changes in the global food system, which is producing more processed, affordable, and effectively marketed food than ever before (Swinburn et al. 2011). The double burden of malnutrition is strictly related to the nutrition transition, the shift in dietary patterns, consumption and energy expenditure associated with economic development over time, often in the context of globalization and urbanization (WHO 2016).

The past decades have seen a decline in adherence to the so-called ‘healthy diets’ such as the ‘Mediterranean diet’ (da Silva et al. 2009). The analysis on diet composition developed in the Food Sustainability Index (FSI 2018) draws the attention to the high intake of nutrients associated with the development of health conditions. For example, sugar in diets expressed as percentage over total calories, goes up to 16% in the United States and Malta, 15% in Mexico, Argentina, Slovakia, Jordan and Sudan (FAO 2013a, b). Meat consumption levels, analyzed as the difference in meat supply quantity from recommended intake, are of 228 g/capita/day in Australia, 225 in the United States, 203 in Argentina and 180 in Luxembourg (FAO 2013a, b; McMichael et al. 2007).Footnote 2

For food system researchers, obesity is the result of people responding normally to the obesogenic environments they find themselves in (Lake and Townshed 2006). Supporting individual choices will continue to be important, but it is here argued that the priority should be for policies addressing specific contexts that might lead to the excessive consumption of energy and nutrients. Policymakers and governments are among the first stakeholders responsible for tackling the issues through education and facilitating access to healthier foods, such as the “Let’s Move” campaign in the United States, as well as through measures to discourage consumption of certain foodstuffs, such as the sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) tax introduced in Mexico in 2013. Although effective in discouraging the consumption of certain foods and moderately leading to improvement in the population’s health, fiscal measures have not come without economic and social downside, which reminds us that none of the interventions can be adopted as a sole solution but must be part of an extensive strategy in public health nutrition. According to a recent review, school-based interventions show promising results to reduce SSB consumption among adolescents (Vézina-Im et al. 2017).

2.1 Nutritional Challenges in the SDGs

A number of SDGs are linked to the global nutritional challenges, besides the SDG number 2 “End hunger”.

-

SDG #1. No poverty

Today millions of people are struggling to satisfy their most basic needs. Poverty and other social inequities are associated with poor nutrition in low, middle and high-income countries, also among certain population subgroups within countries. Addressing poverty will improve nutritional outcomes, just as improving nutrition is essential in the fight against poverty (Perez-Escamilla et al. 2018; Global Nutrition report 2017).

-

SDG #2. Zero Hunger

“End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture” underlines the importance of hunger as a barrier to sustainable development and creating a trap from which people cannot easily escape. A world with zero hunger can positively impact our economies, health, education, equality and social development and is a prerequisite to achieving the other sustainable development goals such as education, health and gender equality (UN 2015).

-

SDG #3. Good Health and Well-Being

“Ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages” addresses all major health priorities, including communicable and non-communicable diseases (NCDs) (UN 2015). Overnutrition is among the major risk factors driving the rise NCDs, including heart disease, stroke, cancer and diabetes and chronic lung disease, collectively responsible for almost 70% of all deaths worldwide (WHO 2018c). NCDs not only threaten development but are also a cause and consequence of poverty, and tackling the NCDs needs to squarely address social inequity (UN 2011). However, due to the very large number of targets and indicators in SDG 3 specifically and the SDGs generally, the NCDs agenda is at real risk of becoming invisible and not being addressed (Ordunez and Campbell 2016).

-

SDG #4. Quality Education

Education is associated with improved nutritional outcomes. Mothers who have had quality secondary school education are likely to have significantly better nourished children. Also, improved nutrition means better outcomes in education, employment and female empowerment, as well as reduced poverty and inequality (Global Nutrition Report 2017).

-

SDG #5. Gender Equality

Guaranteeing equal access to and control over assets raises agricultural output, increases investment in child education and raises household food security. Women’s empowerment within the food-system, from food production to food preparation is a fundamental prerequisite for social and economic development of communities, yet efforts in this direction are hampered by malnutrition (Oniang’o and Mukudi 2002).

-

SDG #6. Clean Water and Sanitation

Billions of people do not have access to safe drinking water and lack adequate hygiene and sanitation services, living at risk of avoidable infections and disease that negatively impact nutritional status and health. Irrigation, the single most important recipient of freshwater withdrawals with potential to influence nutritional outcomes in several ways, has not been given enough attention. Addressing water variability, scarcity and competing uses is beneficial for food security and nutrition (Ringler et al. 2018)

-

SDG #10. Reduced Inequalities

Powerful synergies exist between social protection and food security. Effective social assistance programs can alleviate chronic food insecurity, while demand-driven or scalable social insurance and safety net programs can address transitory food insecurity caused by seasonality or vulnerability to livelihood shocks (HLPE 2012).

-

SDG #12. Responsible Consumption and Production

“Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns” implies that meeting the nutritional needs of a rising population requires consumers to choose, and food systems to provide, a nutritious and safe diet, with a lower environmental footprint. SDG 12 offers clear opportunities to reduce the NCDs burden and to create a sustainable and healthy global scenario.

-

SDG #13. Life on Land

The declining diversity of agricultural production and food supplies worldwide may have important implications for global diets. Agricultural diversification may contribute to diversified diets through both subsistence- and income-generating pathways and may be an important strategy for improving diets and nutrition outcomes in low- and middle-income countries. Additional research is also needed to understand the potential impacts of agricultural diversification on overweight and obesity (Jones 2017).

-

SDG#14. Life Below Water

Healthy water-related ecosystems provide a series of ecosystem services, many of which in turn support nutrition and health outcomes (Ringler et al. 2018)

-

SDG #16. Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

Food security and nutrition can contribute to conflict prevention and mitigation by building and enhancing social cohesion, addressing root causes or drivers of conflict, and by contributing to the legitimacy of, and trust in, governments. Food security can support peace-building efforts and peace-building can reinforce food security (FAO 2016).

-

SDG#17. Partnerships for the Goals

The complexity and the relations between all of the SDGs call require a paradigm shift, calling for all stakeholders of the food system to engage and share knowledge in supporting communities and countries in achieving the SDGs.

3 Food and the Environment

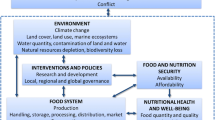

A food system consists of all the elements (environment, people, inputs, processes, infrastructures, institutions, etc.) and activities that relate to the production, processing, distribution, preparation and consumption of food, as well as the outcomes of these activities; namely nutrition and health status, socio-economic growth and equity and environmental sustainability (Mehta et al. 2014). When it comes to agriculture, there exists a paradox concerning the allocation of land and resources for human and animal consumption as well as the production of biofuels: only 55% of the total crop calories produced in the world are eaten by people, as a vast share of the total is used for animal feed (36%) and another 9% goes into biofuels production (Cassidy et al. 2013).

Among all the economic sectors, food production is the one with the highest burden on the environment, with animal products being the most relevant (Steinfeld et al. 2006). The amount of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions which can be linked directly with the production of food is very large, with the quotas found most often in literature ranging between 18% and 51% (Steinfeld 2006; Goodland and Anhang 2009). Moreover, it should be noted that the GHGs emissions from the agricultural sector are constituted mainly by CH4 (52%) and N2O (44%) (Baumert et al. 2005; van Beek et al. 2011): these gases are far more heat absorptive than CO2, respectively 21 and 310 times more.

Food production also affects global water use: on average, as much as 92% of daily personal water footprint can be linked to food (Hoekstra and Mekonnen 2012). This figure accounts for the water used in each step of the life cycle of food production, from the watering of raw ingredients, to the cooling of the packaging plant. A number of countries also externalize their water footprints related to food through trade, a phenomenon that has been referred to as virtual water trade (Allan and Allan 2002). In the EU, for instance, the water-stressed Italy and Spain are major exporters of blue water (Antonelli et al. 2017). Another very important environmental impact is the one related to land. This has many forms, from direct pollution of arable areas with, for example fertilizers and antibiotics, or through an excessive discharge of animal waste, to changes in land use after the deforestation of the Amazon rainforest. This is due to the amount of land converted to grazing areas for livestock, or to grow feed crops, which results in biodiversity loss and land degradation (Gerber et al. 2013). Currently, as much as 80% of the available cropland worldwide is used for animal farming either to grow animal feed ingredients or as pasture (Steinfeld et al. 2006); nearly one-third of global arable land is used for feed production, while of the total share of ice-free Earth’s surface, 26% is dedicated to grazing (FAO 2018c). Moreover, only about 0.002% of global GDP is invested to reverse biodiversity loss (Sumaila et al. 2017).

The environmental impacts of food production, coupled with an increasing demand for animal products worldwide, highlight the importance of the adoption of sustainable diets. This is due mainly to two reasons: firstly, population is projected to continue increasing in the future and so will the need for food (Dubois 2011), and secondly, the average income per capita is expected to rise globally, a factor which traditionally has been linked with a shift towards the consumption of foods with higher environmental impacts (such as animal products—Grigg 1995). The combination of these factors highlights how crucial is the issue of transforming food production and consumption to both ensure the preservation of natural ecosystems, while improving nutritional outcomes. The Mediterranean diet, for instance, is explicitly cited by FAO as an exemplary Sustainable Diet (FAO 2010), besides a diet with well-documented healthy benefits (Sofi et al. 2010; Dernini et al. 2017). In this context, a number of models have been developed to provide quality guidance for sustainable diets, including the Double Pyramid, showing the relationship between a healthy diet and one with a lower environmental impact (BCFN 2016; Ruini et al. 2015), as well as the One Planet Food programme by WWF-UK, aiming to reduce the environmental and social impacts of food consumption in the UK.

In assessing the progress towards a more sustainable food system worldwide (and therefore also the achievement of SDGs), it becomes particularly useful to use monitoring systems that can account for the complexity of the food system and look simultaneously into different dimensions. The FSI (2018) highlights that, some countries perform better than others when it comes to reducing the impact on the environment of their agricultural systems. For example, when it comes to the share of agricultural land under organic farming, Austria, Finland and Estonia lead the way, while South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe fall on the other end of the scale (FAO 2015a, b). Similarly, the highest levels of average carbon content of soil are found in Finland, Rwanda and Estonia, while UAE, Zimbabwe and Egypt lag behind (FAO 2008). However, when looking at other indicators, such as those related to the age of farmers, the countries which perform best are Senegal, Cameroon and Rwanda, while problems might arise in the future in Japan, Portugal and South Korea, where the farmers’ age is much higher (FSI 2018). A more sustainable agricultural system can be achieved with a mix of strategies, harnessing both traditional and new techniques and knowledge. Precision farming, including the use of algorithms to predict which microbes will be most beneficial to the growth of a certain plant, needs to go hand in hand with practices such as cover cropping or agroecology, which improve soil quality and preserve biodiversity. A significant contribution will also come from the cooperation of multiple stakeholders, from NGOs to governments and business. Last, but not least, sustainable food systems need integrated frameworks that align health, nutrition and environmental outcomes (Recanati et al. 2018).

There is a growing consensus regarding how the current food system needs to evolve into a different form in order to address issues like climate change adaptation, food security, nutritional challenges, and its environmental impacts (Garnett 2014). From all the points raised so far, it becomes evident how food is also a central issue for the achievement of the 17 SDGs (UN 2015). In fact, they reiterate the importance of sustainability as an overarching goal for food systems in the context of climate change and economic development (Whitmee et al. 2015). Until 2030, the SDGs will see all countries focusing their efforts towards ending all inequalities, fighting poverty, and tackling climate change. Issues related to food production and consumption, constitute, directly or indirectly, an integral component of all the SDGs (SRC 2016). Moreover, six SDGs state clearly how food is crucial for goals such as ending poverty and hunger; guaranteeing health and wellbeing; responding to climate change and preserving life on land or under water; fostering innovation and education; assuring the inclusion of women and youth and more responsible production and consumption patterns.

3.1 Food and the Environment in the SDGs

A number of SDGs are related to the environment, besides the SDGs number 13 “Climate action”, number 14 “Life below water” and number 15 “Life on Land”. As described below, environmental protection is crucial also for other SDGs.

-

SDG #1. No poverty

Most of the world’s poor people get the highest share of their income through agriculture: supporting sustainable small-scale farming and a diversity in agricultural models is a fundamental step towards poverty reduction (OECD 2011).

-

SDG #2. Zero Hunger

Ensuring access to nutritious food is a pre-requisite for a reduction in environmental degradation. When faced with desperate hunger, people are led to desperate strategies for survival, making the conservation of natural resources less relevant to them (IFPRI 1995). In turn, supporting education and training for an adequate management of natural resources has benefits for hunger reduction.

-

SDG #3. Good health and well-being

A clean environment, without pollution, is essential for well-being and positive effects on health. Specifically, environmental protection and sustainable agricultural production, fosters the achievement of target 3.9 “Reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination”.

-

SDG #5. Gender equity

Women represent 43% of the total agricultural labor force worldwide (FAO 2011a), with shares close to 50% in some regions of Asia and in Sub-Saharan Africa. This makes women an essential contribution to agriculture and rural enterprises in the developing world. Promoting policies and supporting programmes that are targeted at increasing women’s knowledge on sustainable agricultural practices would in turn also provide them with the tools to foster a fairer recognition of their role in society.

-

SDG #6. Clean water and sanitation

As much as 80% of wastewater from municipalities is discharged untreated into water bodies worldwide (WWAP 2017). Agriculture accounts for 70% of water use globally, making it a major player in water pollution, as farms also discharge agrochemicals, drug residues, sediments etc. into water bodies. The pollution resulting from this process affects aquatic ecosystems, human health and productive activities (UNEP 2016). Less polluting agricultural practices can have significant benefits for a higher level of cleanliness in water resources worldwide.

-

SDG #11. Sustainable cities and communities

By 2025, more than half of the world’s population will be urban. The sustainable urban and peri-urban horticulture will play a crucial role in making cities more sustainable (FAO 2011b).

-

SDG #12. Responsible consumption and production

The production of food globally creates the largest pressure on Earth, with effects on water, land use and greenhouse gas emissions which threaten local ecosystems (Willett et al. 2019). A more sustainable food system and more sustainable dietary habits would be crucial to achieve this goal.

-

SDG #13. Climate Action

Food production, and animal products in particular, is responsible for a significant share of GHG emissions, up to 51% according to Goodland and Anhang (2009). The transition to a more plant-based diet has been indicated as the single most significant action towards a reduction of the impact on Earth, including GHG emissions (Poore and Nemecek 2018).

-

SDG #14. Life below water

Industrial agriculture and farming can be linked also with ocean pollution, as in the case of “ocean dead zones”: these are the result of large scale animal farming, often referred to as Concentrated Automated Feeding Operations—CAFOs (Imhoff 2010) and are formed by untreated animal waste, which creates runoff, reaches the water streams and then collects in the ocean. The animal waste is in such a high concentration that it depletes the oxygen available in the pre-existing ocean ecosystem. Changing such agricultural structures to alternatives which prevent runoff, and reducing other types of water pollution from agriculture can have a significant effect on improving the quality of life in the oceans.

-

SDG #15. Life on land

More sustainable agricultural practices can play a big role in halting the ongoing massive degradation of biodiversity and ecosystem services (Ceballos et al. 2017). Ensuring that higher levels of biodiversity are preserved in the agricultural systems, for example with the use of agroecology, allows for processes such as nutrients recycling and microclimate regulation, which are essential for all life on land.

-

SDG #17. Partnerships for the goals

Given the central role of food in the achievement of SDGs, partnerships which are developed specifically to increase the sustainability of the food sector and to include perspectives of all stakeholders can play a positive role. This is the case of multi-stakeholder partnerships (MSPs), an organizational form with an increasingly important role in global governance and in which public and private actors combine their efforts to reach a common approach to the same problem that affects all of them (Selsky and Parker 2005; Roloff 2008; Rasche 2012). Examples in the context of food and agriculture include the Water Footprint Network, the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil and the Global Roundtable for Sustainable Beef (GRSB).

4 Food Loss and Waste

Every year, a third of the world’s food production along the entire supply chain is wasted (Gustavsson et al. 2011). Food production encompasses land, water usage as well as all the GHG associated to agriculture (FAO 2015b; BCFN 2012). And the waste of these natural resources due to the phenomenon of food losses and waste (FLW) ultimately has repercussions on income, on the economic growth, on nutrition and on individuals’ hunger (FAO 2015b). Due to its importance, the reduction of FLW have been integrated in the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Specifically, the SDG number 12 “Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns” encompasses the issue in its third target: “by 2030, halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses” (SDG 12.3, UN 2015). That is why it is fundamental that institutions, government, scientific communities, media, and individuals deeply understand the phenomenon and try to put forward whatever they can do to reduce it.

According to FAO (Gustavsson et al. 2011), food losses refer to avoidable edible waste that occur at the agricultural, post-harvest, and processing phases of the food supply chain, and are mainly due to poor infrastructure and investments. While food waste specifically happens in the last phases of the food supply chain, that is at retail and consumption level and are specifically due to behavioral issues (Parfitt et al. 2010; Principato 2018). Concerning the amount, although industrialized and developing countries almost discard the same amount of food (respectively 670 and 630 million tons every year), in the developing countries 40% of losses happen at post-harvest and processing phases, while in industrialized countries more than 40% of waste occur at retail and consumer ones (Gustavsson et al. 2011). Considering the type of food, globally every year 30% of cereals, 40–50% of root crops, fruits and vegetables, 20% for oil seeds, meat and dairy, and about 35% of fish get lost or wasted (Gustavsson et al. 2011). Food waste causes an exploitation of natural resources: land, water and related carbon emissions due to the production of food that ultimately ends up in the trash. FAO (2013a, b) highlighted that if food waste could be a country, it would be the third top greenhouse gas emitters after China and USA. The global economic cost of FLW, that encompasses not only the financial aspect, but also the social and environmental impacts, is estimated to almost 2.6 trillion of US Dollars (FAO 2014). The social impacts of FLW are related to the issue of food security and food access. To make an example, food waste, that occurs in the rich countries (222 million tons) represents the net food production of Sub-Saharan Africa (222 million tons) (Gustavsson et al. 2011).

FLW represents a multi-faceted problem that should be addressed with the commitment of all the actors involved, starting from governments and policy makers. According to the FSI (2018), some countries are already at a good well under way, while some others needs some important changes. France, Argentina, and Luxemburg, for instance, have an excellence policy involvement against FLW. In France, it is noteworthy the proactive legislation of 2016 that prohibits big supermarkets to waste unsold food, requiring them to sell at a smaller price or to donate to people in need. This result in an annual food waste per capita of 67 kg, a good achievement if we consider, for instance, that countries like United States wastes 95 kg per capita (the highest amount in the FSI ranking). Another practice that is necessary is setting reduction or prevention quantitative targets on FLW, this is important, not only to align to the SDGs targets, but also to measure how policies and initiatives against FLW are effective. Indeed, all the top three countries of the ranking (France, Argentina and Luxembourg), aligning to the majority of high-income ones, encompass specific food waste reduction targets. Among the high-income countries that still do not have reduction targets there are Canada and Italy. Relevant good practices happen also in the southern part of the world. In Egypt, for instance, it has been introduced a smartcard system to limit the daily amount of subsidized bread for each family to reduce the demand for bread consequent food waste. In Lebanon civil-society organizations, like Food Establishments Recycling Nutrients and the Lebanese Food Bank, have taken the lead in tackling the problem of food waste by promoting no-waste campaigns and distributing surplus food. In Australia food donations are fully tax deductible, and in Saudi Arabia there are voluntary agreements in place to deal with reducing food waste. For example, the General Sports Authority has signed an agreement with the Saudi Food Bank that aims to promote the reduction of food loss, for example through the launch of a food conservation prize targeting hotels and restaurants (FSI 2018).

The UAE, Malta and Turkey are instead performing the worst result among the 67 countries considered (FSI 2018). In particular, UAE has the highest percentage of food losses, that is 59% of total food production is discarded during the first stages of the food supply chain (FAO 2013a, b) and has no policy response and a national plan to tackle food losses and waste. Similarly, Turkey has a high percentage of food losses (9% of total food production) and at the moment, no policy response is put forward against it. Malta has a high rate of food losses (9% of total food production), but contrary to the others two countries attempts to have a food loss strategy, that is the National Agricultural Policy for the Maltese Islands 2018–2028. This policy considers, among its economic objectives, reducing product loss in order to increase value addition and to identify new export markets. Malta has also a high number of food waste per capita, 52 kg per year, but there is almost no policy response to this issue.

FLW is a complex issue that involves a number of stakeholders at the different stages of the FSC. In particular farmers, food producers, and distributors for the first stages of the FSC, and retailers and individuals during the last stages. Considering the first stages of the FSC, the main recommendation would be to develop supply chain agreements between farmers, producers, and distributors for more appropriate planning of food supply, along with investing in better road infrastructure and storage facilities in order to transport and preserve food correctly. At the individual’s level, since it has been acknowledged that FLW mainly happens for behavioral issues (Parfitt et al. 2010; Principato 2018), it is fundamental to increase consumer awareness about waste and on how to better plan, purchase, preserve, prepare, and ultimately redistribute, and dispose food. Along with this, it is necessary to have the involvement of policy makers both at international, national, and local level in order to implement FLW policies and set targets for improvement. Academia and third sector/private initiatives also play a role: the former should continue to analyze the phenomenon and set a clearer methodology to define and quantify it; the second one is fundamental in creating a bridge between food companies/retailers and food banks/charities in order to redistribute food to people in need.

4.1 Food Loss and Waste in the SDGs

A number of SDGs are related to FLW, besides the SDG number 12 “Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns”. As analyzed below, addressing FLW is essential in the accomplishment of a number of other SDGs.

-

SDG #1. No poverty

Food waste is a waste of money: the social cost related to it amounts to $940 billion per year (FAO 2014). Reducing it can save Countries budget and household money, thus relieving poverty.

-

SDG #2. Zero Hunger

It has been estimated that 45% of all fruit and vegetables, and about 20% of meat gets wasted, as highlighted in the BCFN third paradox, this is not a comforting fact in a growing population that is still suffering hunger (Gustavsson et al. 2011).

-

SDG #9. Industry Innovation and Infrastructure

Thanks to the rising of sharing economy and digital technology, food sharing models are emerging. It has been seen that they could represent an innovative way to share excess food, thus avoiding waste, while fostering innovations and sustainable development (Michelini et al. 2018).

-

SDG #10. Reduce inequalities

It has been shown that reducing food losses in the Developing Countries could lead to less inequality within and among countries, due to the money saved from food losses reduction (Gustavsson et al. 2011).

-

SDG #11. Sustainable cities and communities

Food waste reduction at consumer and retail level, the promotion of sorting practices at community level (like policies to increase composting), and the use of food sharing platforms, could lead to more sustainable cities and societies (Michelini et al. 2018; Secondi et al. 2015).

-

SDG #12. Responsible consumption and production

From the consumer perspective, it is worth noting that individuals that are more aware of food waste impacts tend to waste less (Principato et al. 2015). From the retailer perspective, initiatives like “buy one, get the second free later” that propose the 2X1 marketing offer but with the option of getting the second one when necessary, represent a valuable production initiative (Mondéjar-Jiménez et al. 2016). From the food company perspective, we should mention the report of Champions 12.3 that highlighted that companies that invest $1 in the reduction of food losses and waste along their food supply chain, can pursue a return of investment of up to $14 (Champions 12.3, 2017).

-

SDG #13. Climate Action

FLW produces about 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions (CAIT 2015). It has been demonstrated that reducing FLW would limit emissions of planet-warming gases, lessening some of the impacts of climate change, such as more extreme weather conditions and rising seas (Hiç et al. 2016).

-

SDG #14. Life below water

Food that is produced but not eaten produce a volume of water comparable to the annual flow of Russia’s Volga River (FAO 2013a, b).

-

SDG #15. Life on land

FLW reduction could save 30% of arable land, which is yearly used to cultivate, or farm wasted food (FAO 2013a, b).

-

SDG #17. Partnerships for the goals

Food waste can be tackled only with the involvement of all the stakeholders (institutions, individuals, companies, NGOs and academia) and the creation of inclusive partnerships.

5 The Pathway Towards Sustainable and Healthy Food Systems

This chapter has attempted to highlight some of the issues that global food systems are currently facing. A few recommendations can be drawn on how to progress towards the establishment of sustainable and healthy food systems that pave the way to sustainable development, both “a way of understanding the world and a method for solving global problems” (Sachs 2015, p. 1).

In the current food system, for every US$1 spent on food, US$2 is incurred in economic, societal, and environmental societal costs, (totaling USD 5.7 trillion/year) due to both food production and to the consequences of consumption (Ellen MacArthur Foundation 2019). A number of interventions can be put forward to accelerate the transition to a healthier and more sustainable food systems. These measures, at the public level, include use regulations or financial incentives, applying taxes or charges for certain types of foodstuff, running mass information campaigns, providing food-related education in schools (Willett et al. 2019). Policy can play a crucial role in enabling transformative change by removing barriers while providing incentives to influence stakeholders’ behaviors; ensure transparency and accountability of operators; mobilize public and private resources for addressing priority areas; ensuring coherent and integrated policies, beyond the agricultural sector, as food fundamentally cross-cuts a number of sectors (Rawe et al. 2019). At the city level, policies for food system transformation can address local challenges, encourage citizens engagement (Rawe et al. 2019). A number of umbrella organizations and initiatives, such as the C40 Food Systems Network and the Milan Urban Food Policy Act, have shown that urban food policies have the potential for both scaling up and out good practices. Business interventions range from sustainable farming initiatives and reshape of supply chains, to product reformulation and prioritization of sustainable and healthy products in marketing (Willett et al. 2019). Given the scope of the challenge, there is an increasing urgency to develop a society-wide response to food system challenges, that encompasses people’s mindset and behavior. Consumers can orient business practices by modifying their behavior to support environmental objectives through sustainable purchasing choices, therefore increasing public understanding and awareness is crucial for its potential to shape decisions, consumption, and lifestyles (Bartels et al. 2013).

Education, new technologies and bottom-up solutions-based approaches are also important ingredients for a food system transition. As we strive to reach the SDGs, it is important to reimagine how to educate the future generations of leaders in the policy, business and civil society domains. Obtaining a quality education, as prescribed in SDG 4, is a major driver of sustainable development and the foundation to creating sustainable food systems. As such, education is linked to all the areas analyzed in this chapter, from improving the nutritional quality of diets to prevent end-user food waste. Management education will also require a fundamental overhaul, by considering the SDGs as targets to be achieved, thus going beyond the concept of shareholder value maximization (Davis 2018). New and traditional knowledge will need to go together towards the same direction in order to ensure that food production becomes more sustainable. Agroecology principles can offer a wide range of low-impact techniques that assist not only a more ecologically friendly food production and higher levels of biodiversity, but also water conservation and soil fertility improvements; for these reasons, also the FAO has recently launched an initiative to scale-up agroecology and favor the achievement of SDGs. Also new digital tools can bring benefits, for example in increasing efficiency, sparing environmental resources and reducing the use of chemicals thanks to a greater real-time data availability. For example, in Italy a project is being implemented by CREA and the Italian Ministry of Agriculture to develop sustainable biotechnologies. Enabling the scale up and out of bottom-up solutions is increasingly recognized as potentially transformative of food systems globally, as witnessed by initiatives such as the Global Opportunity Explorer from the United Nations Global Compact.

An integrated framework establishing a safe operating space for global food systems to feed a population of ten billion people with a healthy and sustainable diet has been defined by the EAT-Lancet Commission report, calling for a “Great Food Transformation” (Willett et al. 2019). The pathway envisioned includes major transformation in diets (the healthy diet consists mainly of vegetable, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts and unsaturated oils) so to stay within planetary boundaries in terms of climate change, land-use systems, water use, biodiversity loss etc.

Sustainable development is a universal challenge and a shared responsibility of all countries (which are increasingly interdependent) and actors in society, and requires a fundamental overhaul in the way we produce and consume food with a holistic approach that considers both the socio-economic and ecological dimensions. Any transformational change can only be achieved by means of integrated, multisector and multilevel action and the collaboration of all stakeholders, involved or touched upon by food systems.

Notes

- 1.

United Nations Secretary-General. Remarks at High-level Event on Climate Change, 26 September 2018. Retrieved on December 18, 2018: https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/speeches/2018-09-26/remarks-high-level-event-climate-change.

- 2.

In the first case, sugar is calculated as the actual consumption, while in the second, meat consumption is based on the market availability to consumers, specific of a food system in a country.

References

Alexandratos, N., & Bruinsma, J. (2012). World agriculture towards 2030/2050: The 2012 revision (Vol. 12, No. 3) (ESA working paper). Rome: FAO.

Allan, J. A., & Allan, T. (2002). The Middle East water question: Hydropolitics and the global economy (Vol. 2). London: Ib Tauris.

Antonelli, M., Tamea, S., & Yang, H. (2017). Intra-EU agricultural trade, virtual water flows and policy implications. Science of the Total Environment, 587, 439–448.

Bailey, R. L., West, K. P., Jr., & Black, R. E. (2015). The epidemiology of global micronutrient deficiencies. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 66.(Suppl 2, 22–33.

Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition. (2012). Food waste: Causes, impacts and proposals. Report.

Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition. (2016). Double Pyramid 2016: A more sustainable future depends on us. Parma: BCFN.

Bartels, W. L., Furman, C. A., Diehl, D. C., Royce, F. S., Dourte, D. R., Ortiz, B. V., Zierden, D. . F., Irani, T. . A., Fraisse, C. . W., & Jones, J. W. (2013). Warming up to climate change: A participatory approach to engaging with agricultural stakeholders in the southeast US. Regional Environmental Change, 13(1), 45–55.

Baumert, K. A., Herzog, T., & Pershing, J. (2005). Navigating the numbers. Greenhouse Gas Data and International Climate Policy. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. Retrieved from http://pdf.wri.org/navigating_numbers.pdf.

CAIT. (2015). Climate data explorer. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute.

Cassidy, E. S., West, P. C., Gerber, J. S., & Foley, J. A. (2013). Redefining agricultural yields: From tonnes to people nourished per hectare. Environmental Research Letters, 8(3), 034015.

Ceballos, G., Ehrlich, P. R., & Dirzo, R. (2017). Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signaled by vertebrate population losses and declines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(30), E6089–E6096.

Champions 12.3. (2017). Road map to achieving SDG target 12.3. Retrieved from https://champs123blog.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/champions-123-roadmap-to-achieving-sdg-target-123.pdf.

Da Silva, R., Bach-Faig, A., Quintana, B. R., Buckland, G., de Almeida, M. D. V., & Serra-Majem, L. (2009). Worldwide variation of adherence to the Mediterranean diet, in 1961–1965 and 2000–2003. Public Health Nutrition, 12(9A), 1676–1684.

Davis, J. (2018). Management education for sustainable development. Stanford for Social Innovation Review, 18, 2018. Retrieved from https://ssir.org/articles/entry/management_education_for_sustainable_development#.

Dernini, S., Berry, E. M., Serra-Majem, L., La Vecchia, C., Capone, R., Medina, F. X., Aranceta-Bartrina, J., Belahsen, R., Burlingame, B., Calabrese, G., & Corella, D. (2017). Med Diet 4.0: The Mediterranean diet with four sustainable benefits. Public Health Nutrition, 20(7), 1322–1330.

Development Initiatives. (2017). Global Nutrition Report 2017: Nourishing the SDGs. Bristol: Development Initiatives.

Dubois, O. (2011). The state of the world’s land and water resources for food and agriculture: Managing systems at risk. London: Earthscan.

Ellen MacArthur Foundation. (2019). Cities and circular economy for food. Retrieved from http://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/publications.

FAO. (2008). Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/faostat/.

FAO. (2010). Sustainable diets and biodiversity. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/3/i3004e/i3004e.pdf.

FAO. (2011a). The role of women in agriculture. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/docrep/013/am307e/am307e00.pdf.

FAO. (2011b). Growing greener cities. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/ag/agp/greenercities/pdf/ggc-en.pdf.

FAO. (2013a). Food wastage footprint: Impacts on natural resources. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3347e/i3347e.pdf.

FAO. (2013b). Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FBS.

FAO. (2014). Food wastage footprint: Full-cost accounting. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3991e.pdf.

FAO. (2015a). The state of food insecurity in the world. In Meeting the 2015 International Hunger Targets: Taking Stock of Uneven Progress.

FAO. (2015b). Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/faostat/.

FAO. (2016). Food security, nutrition and peace. In Proceedings of the United Nations Security Council meeting, New York, 29 March, 2016.

FAO. (2017). The future of food and agriculture—Trends and challenges. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

FAO. (2018a). The impact of disasters and crises on agriculture and food security. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

FAO. (2018b). Transforming food and agriculture to achieve the SDGs. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

FAO. (2018c). Animal production. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/animal-production/en/.

FAO. (2019). FAO AQUASTAT. Retrieved December 18, 2018, from www.fao.org.

FSI (The Food Sustainability Index). (2018). Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition and The Economist Intelligence Unit. Retrieved from http://foodsustainability.eiu.com/.

Garnett, T. (2014, June). Changing what we eat: A call for research & action on widespread adoption of sustainable healthy eating. Food Climate Research Network. Retrieved from http://www.fcrn.org.uk/sites/default/files/fcrn_wellcome_gfs_changing_consumption_report_final.pdf.

Gerber, P. J., Steinfeld, H., Henderson, B., Mottet, A., Opio, C., Dijkman, J., Falcucci, A., & Tempio, G. (2013). Tackling climate change through livestock: A global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

Goodland, R., & Anhang, J. (2009). Livestock and climate change. What if the key actors in climate change were pigs, chickens and cows? (pp. 10–19). Washington, DC: Worldwatch Institute.

Grigg, D. (1995). The pattern of world protein consumption. Geoforum, 26(1), 1–17.

Gustavsson, J., Cederberg, C., Sonesson, U., Van Otterdijk, R., & Meybeck, A. (2011). Global food losses and food waste (pp. 1–38). Rome: FAO.

Hawkes, C., Harris, J., & Gillespie, S. (2017). Changing diets: Urbanization and the nutrition transition (pp. 34–41). Washington, DC: IFPRI. https://doi.org/10.2499/9780896292529_04.

Hiç, C., Pradhan, P., Rybski, D., & Kropp, J. P. (2016). Food surplus and its climate burdens. Environmental Science & Technology, 50(8), 4269–4277.

HLPE. (2012). Social protection for food security. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security. Rome: CFS.

Hoekstra, A. Y., & Mekonnen, M. M. (2012). The water footprint of humanity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(9), 3232–3237.

IFPRI. (1995). Poverty, food security and the environment (Brief 29). Retrieved from https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/16346/1/br29.pdf.

Imhoff, D. (2010). The CAFO Reader: The tragedy of industrial animal factories. London: Watershed Media.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC]. (2018). Summary for policymakers. In V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, H. O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P. R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J. B. R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M. I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, & T. Waterfield (Eds.), Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Geneva: World Meteorological Organization, 32 pp. Retrieved December 18, 2018, from https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/.

Jones, A. D. (2017). Critical review of the emerging research evidence on agricultural biodiversity, diet diversity, and nutritional status in low-and middle-income countries. Nutrition Reviews, 75(10), 769–782.

Keefe, M. (2016). Nutrition and equality: Brazil’s success in reducing stunting among the poorest. In S. Gillespie, J. Hodge, S. Yosef, & R. Pandya-Lorch (Eds.), Nourishing millions: Stories of change in nutrition, Ch. 11 (pp. 99–105). Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). https://doi.org/10.2499/9780896295889_11.

Lake, A., & Townshend, T. (2006). Obesogenic environments: Exploring the built and food environments. The Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health, 126(6), 262–267.

McMichael, A. J., Powles, J. W., Butler, C. D., & Uauy, R. (2007). Food, livestock production, energy, climate change, and health. The Lancet, 370(9594), 1253–1263.

Mehta, L., Cordeiro-Netto, O., Oweis, T., Ringler, C., Schreiner, B., & Varghese, S. (2014). High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE). Project team for the report on Water and Food Security.

Michelini, L., Principato, L., & Iasevoli, G. (2018). Understanding food sharing models to tackle sustainability challenges. Ecological Economics, 145, 205–217.

Mondéjar-Jiménez, J. A., Ferrari, G., Secondi, L., & Principato, L. (2016). From the table to waste: An exploratory study on behaviour towards food waste of Spanish and Italian youths. Journal of Cleaner Production, 138, 8–18.

OECD. (2011). Agricultural progress and poverty reduction. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/tad/agricultural-policies/48478345.pdf.

Oniang’o, R., & Mukudi, E. (2002). Nutrition and gender. Nutrition: A foundation for development (Brief 7). Geneva: ACC/SCN.

Ordunez, P., & Campbell, N. R. (2016). Beyond the opportunities of SDG 3: The risk for the NCDs agenda. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 4(1), 15–17.

Parfitt, J., Barthel, M., & Macnaughton, S. (2010). Food waste within food supply chains: Quantification and potential for change to 2050. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 365(1554), 3065–3081.

Perez-Escamilla, R., Bermudez, O., Buccini, G. S., Kumanyika, S., Lutter, C. K., Monsivais, P., & Victora, C. (2018). Nutrition disparities and the global burden of malnutrition. British Medical Journal, 361, k2252.

Poore, J., & Nemecek, T. (2018). Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science, 360(6392), 987–992.

Principato, L. (2018). Food waste at consumer level: A comprehensive literature review. Cham: Springer.

Principato, L., Secondi, L., & Pratesi, C. A. (2015). Reducing food waste: An investigation on the behaviour of Italian youths. British Food Journal, 117(2), 731–748.

Rasche, A. (2012). Global policies and local practice: Loose and tight couplings in multi-stakeholder initiatives. Business Ethics Quarterly, 22(4), 679–708. https://doi.org/10.5840/beq201222444.

Rawe, T., Antonelli, M., Chatrychan, A., Clayton, T., Falconer, A., Fanzo, J., Gonsalves, J., Matthews, A., Nierenberg, D, & Zurek, M. (2019). Catalysing transformations in Global Food Systems under a changing climate. CCAFS Info Note. Wageningen: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture, and Food Security (CCAFS), forthcoming.

Recanati, F., Maughan, C., Pedrotti, M., Dembska, K., & Antonelli, M. (2018). Assessing the role of CAP for more sustainable and healthier food systems in Europe: A literature review. Science of the Total Environment, 653, 908–919.

Ringler, C., Choufani, J., Chase, C., McCartney, M., Mateo-Sagasta, J., Mekonnen, D., & Dickens, C. (2018). Meeting the nutrition and water targets of the Sustainable Development Goals: Achieving progress through linked interventions. Colombo, Sri Lanka: International Water Management Institute (IWMI). CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystems (WLE); Washington, DC, USA: The World Bank. 24p. (WLE Research for Development (R4D) Learning Series 7). https://doi.org/10.5337/2018.221.

Roloff, J. (2008). Journal of Business Ethics, 82, 233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9573-3.

Ruini, L. F., Ciati, R., Pratesi, C. A., Marino, M., Principato, L., & Vannuzzi, E. (2015). Working toward healthy and sustainable diets: The “Double Pyramid Model” developed by the Barilla Center for Food and Nutrition to raise awareness about the environmental and nutritional impact of foods. Frontiers in Nutrition, 2, 9.

Sachs, J. D. (2015). The age of sustainable development. New York: Columbia University Press.

Secondi, L., Principato, L., & Laureti, T. (2015). Household food waste behaviour in EU-27 countries: A multilevel analysis. Food Policy, 56, 25–40.

Selsky, J. W., & Parker, B. (2005). Cross-sector partnerships to address social issues: Challenges to theory and practice. Journal of Management, 31(6), 849–873. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279601.

Sofi, F., Abbate, R., Gensini, G. F., & Casini, A. (2010). Accruing evidence on benefits of adherence to the Mediterranean diet on health: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 92(5), 1189–1196.

Steinfeld, H., Gerber, P., Wassenaar, T., Castel, V., Rosales, M., & de Haan, C. (2006). Livestock’s long shadow: Environmental issues and options (p. 390). Rome: FAO.

Stockholm Resilience Centre. (2016). How food connects all the SDGs. Retrieved from http://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/research-news/2016-06-14-how-food-connects-all-the-sdgs.html.

Sumaila, U. R., Rodriguez, C. M., Schultz, M., Sharma, R., Tyrrell, T. D., Masundire, H., Damodaran, A., Bellot-Rojas, M., Maria, R., Rosales, P., Jung, T. Y., & Hickey, V. (2017). Investments to reverse biodiversity loss are economically beneficial. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 29, 82–88.

Swinburn, B., & Egger, G. (2002). Preventive strategies against weight gain and obesity. Obesity Reviews, 3(4), 289–301.

Swinburn, B. A., Sacks, G., Hall, K. D., McPherson, K., Finegood, D. T., Moodie, M. L., & Gortmaker, S. L. (2011). The global obesity pandemic: Shaped by global drivers and local environments. The Lancet, 378(9793), 804–814.

UN General Assembly. (2015, October 21). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development.

UNEP. (2016). A snapshot of the world’s water quality: Towards a global assessment. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

United Nations. (2015), Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Retrieved January 11, 2019, from https//:sustainabledevelopment.un.org.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2014). World urbanization prospects: The 2014 revision, highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/352).

United Nations General Assembly. (2011, September 16). Sixty-sixth sessions. Political declaration of the high-level meeting of the general assembly on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. A/66/L.1. New York: United Nations. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/es/comun/docs/?symbol=A/66/.

United Nations World Water Assessment Programme (WWAP). (2017). The United Nations World Water Development Report 2017: Wastewater, the untapped resource. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Van Bavel, J. (2013). The world population explosion: Causes, backgrounds and projections for the future. Facts, Views & Vision in ObGyn, 5(4), 281.

Van Beek, C. L., Pleijter, M., & Kuikman, P. J. (2011). Nitrous oxide emissions from fertilized and unfertilized grasslands on peat soil. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems, 89(3), 453–461.

Vézina-Im, L. A., Beaulieu, D., Bélanger-Gravel, A., Boucher, D., Sirois, C., Dugas, M., & Provencher, V. (2017, September). Efficacy of school-based interventions aimed at decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among adolescents: A systematic review. Public Health Nutrition, 20(13), 2416–2431. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017000076. Epub 2017 Feb 8. Review. PMID: 28173882.

Victora, C. G., Aquino, E. M., do Carmo Leal, M., Monteiro, C. A., Barros, F. C., & Szwarcwald, C. L. (2011, May 28). Maternal and child health in Brazil: Progress and challenges. Lancet, 377(9780), 1863–1876. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60138-4. Epub 2011 May 9.

Whitmee, S., Haines, A., Beyrer, C., Boltz, F., Capon, A. G., de Souza Dias, B. F., Ezeh, A., Frumkin, H., Gong, P., Head, P., & Horton, R. (2015). Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: Report of the Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health. The Lancet, 386(10007), 1973–2028.

Willett, W., Rockström, J., Loken, B., Springmann, M., Lang, T., Vermeulen, S., Garnett, T., Tilman, D., DeClerck, F., Wood, A., & Jonell, M. (2019). Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. The Lancet, 393(10170), 447–492.

World Economic Forum. (2019). The global risks report 2019. 14th ed. Retrieved January 17, 2019, from http://www3.weforum.org.

World Health Organization. (2016). The double burden of malnutrition: Policy brief. World Health Organization. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/255413.

World Health Organization. (2018a, February). Obesity and overweight fact sheets. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

World Health Organization. (2018b). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2018: Building climate resilience for food security and nutrition. Rome: Food & Agriculture Org.

World Health Organization. (2018c). Noncommunicable diseases fact sheet. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Allievi, F., Antonelli, M., Dembska, K., Principato, L. (2019). Understanding the Global Food System. In: Valentini, R., Sievenpiper, J., Antonelli, M., Dembska, K. (eds) Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals Through Sustainable Food Systems. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23969-5_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23969-5_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-23968-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-23969-5

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)