Abstract

Spondyloarthritis is an overlapping family of inflammatory arthritides without known serologic markers that are characterized by the presence of enthesitis and new bone formation. While the majority of conditions affect the spine, peripheral joint involvement also may occur. Diagnosis involves a thorough history, physical exam, and imaging studies. Although treatment modalities are evolving, NSAIDs remain a hallmark of treatment. TNF-α inhibitors are frequently used and specific interleukin inhibitors are becoming more prevalent. Patients with spondyloarthritis require long-term monitoring and frequently require physical and occupational therapy.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Spondyloarthritis (previously referred to as seronegative spondyloarthropathies, herein abbreviated as SpA) is an overlapping family of disorders that share clinical features involving oligoarthritis, enthesitis, and dactylitis. The different types of spondyloarthritis are divided into two categories based upon axial versus peripheral joint involvement. Axial SpA includes predominantly ankylosing spondylitis (AS), non-radiographic axial SpA (nr-SpA), and undifferentiated SpA. AS is a type of inflammatory spine disease affecting primarily the sacroiliac (SI) joints causing back pain, stiffness, and ultimately spinal fusion. nr-SPA is defined as clinical AS without radiographic (X-ray) features but MRI features are evident. Undifferentiated SpA is defined as clinical symptoms or findings of a spondyloarthritis, but no classifiable diagnosis; generally, only SI involvement is present. The classical peripheral SpA, psoriatic (PsA), reactive, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)-associated SpA can involve the spine as well. Psoriatic arthritis is defined as an inflammatory arthritis in patients with skin psoriasis. Reactive arthritis is an inflammatory arthritis that develops in the setting of inciting event, such as infection, usually in the genitourinary or gastrointestinal tract. IBD-associated arthritis is an inflammatory arthritis in the setting of Ulcerative Colitis or Crohn’s Disease. Sometimes, these disease processes act in a distinct manner, but there is oftentimes overlap with features of multiple processes. One of the hallmarks of this family of diseases is seronegativity for rheumatoid factor.

Pathophysiology/Etiology

The main pathophysiologic features that differentiate SpA from other classes of inflammatory arthritides include enthesitis and bone formation. Enthesitis, which is defined as inflammation of the insertion site of tendons or ligaments to bones is a specific finding for SpA [1]. Enthesitis is now believed to be a more diffuse process that involves adjacent bone and soft tissue. Repeated biomechanical stress at this site is thought to cause microdamage that then triggers synovial inflammation leading to synovitis [2]. The most common sites of enthesitis are the Achilles’ tendon, tibial tuberosity, and iliac crest. In the axial diseases, bone formation occurs not in the vertebral body, but more at the periosteum-cartilage junction. Acute and chronic spondylitis with destruction and rebuilding of the cortex and spongiosa occurs. Square vertebral body development occurs due to a combination of destructive osteitis and repair [3].

While the precise trigger(s) for SpA remain unknown, several mechanisms are supported in the literature. First, there is a strong genetic component. Within AS, the MHC class I allele HLA-B27 is strongly associated with disease. The prevalence of the HLA-B27 gene is 80–95% in individuals with AS, but only 5% of individuals in the general population with a positive HLA-B27 will go on to develop AS. Thus, the presence of HLA-B27 positivity portends 20–25% risk for AS, which increases to 40% if the individual also has a first-degree relative with AS [4].

Additional genetic risk loci in large population studies have further pointed toward altered immune function in the etiology of disease [5]. There is an emerging component of SpA pathogenesis involving HLA-B27 misfolding related to accumulation within cells leading to SpA. Improperly folded HLA-B27 proteins can accumulate in the endoplasmic reticulum, and cause activation of the IL-23/IL-17 pathway. While HLA-B27 appears to have the largest contribution in pathogenesis, there are also non-MHC genes that have been noted in the pathogenesis of SpA. Other important genes include IL-17, IL-23, ERAP1/2, TNF family, and the IBD associated genes. Some of these pathways including IL-17, IL-23, and the TNF family are therapeutic targets in SpA.

Cyclooxygenases (COX) and other proinflammatory compounds such as prostaglandins have been found to have an important role, and also constitute a therapeutic target. COX-2 is an inducible enzyme involved in the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandin E2, which is involved in bone metabolism, and explains how continuous NSAID usage can prevent radiographic progression of spondylosis by inhibiting bone formation [3].

There is also a large overlap with inflammatory bowel disease, and there are at least 65 known genes overlapping between AS and Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Some of these gene overlaps cause either clinical or subclinical gastrointestinal symptoms. The hypothesis regarding the GI/SpA overlap is based upon the thought of defects in the GI mucosal barriers allowing a systemic immune response with the activation of IL-23. Th17 cells then secrete IL-17 and stimulate TNF-alpha producing monocytes that initiates the development of SpA [6].

Epidemiology

In the United States, the overall prevalence of all forms of SpA is 0.9% (CI 0.7–1.1), and is higher in women (1.3 vs 0.4%) [7]. AS has a prevalence in the United States of 0.13% [8]. The prevalence of AS is less in other continents, in Europe being 0.12–1.0%, Asia 0.17%, Latin America 0.1%, and Africa 0.07% [9]. PsA in the United States has a prevalence between 0.10% and 0.16%. There is limited data with regard to the prevalence of IBD-SpA, but Italian studies have shown 0.09% and Swedish studies 0.02%. Reactive arthritis has a prevalence between 0.09% and 1.0% [10].

Diagnosis

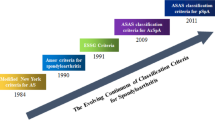

The diagnosis of SpA is based largely upon the history, physical exam, and imaging. The Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society (ASAS) classification criteria were developed to categorize research subjects with either axial or peripheral disease but have not been validated for clinical use (Table 8.1) [11]. Nevertheless, these criteria establish a guide for a clinician’s assessment of a patient with suspected SpA.

Patient History

The patient history is an important feature in the diagnosis of SpA. Classic historical features involve inflammatory back pain, enthesitis, peripheral arthritis, and dactylitis. The cornerstone for diagnosis of axial SpA is dependent on the patient reporting the presence of inflammatory back pain lasting longer than 3 months, which began in an individual before the age of 45 years old. Inflammatory back pain is defined as having an insidious onset, improving with exercise and not with rest, and oftentimes pain at night that improves upon getting up and moving. Peripheral SpA is based upon a history of oligoarticular arthritis, enthesitis, or dactylitis. There are other historical non-musculoskeletal features that are important to elucidate and include inflammatory eye symptoms (photophobia, blurred vision), inflammatory bowel symptoms (diarrhea, hematochezia), recent GI or GU infection, and psoriasis. As one hallmark of SpA is a favorable response to NSAIDs, it is useful to assess if the patient has tried these drugs and their effect on the presenting symptoms. Finally, family history of SpA, psoriasis, uveitis/iritis, or IBD should be assessed.

Physical Exam

On physical exam, it is important to evaluate for axial, peripheral, and non-musculoskeletal findings. Axial symptoms can be investigated by looking for low back pain associated with sacroiliac joint tenderness and decreased range of motion. There are multiple objective measurements that can be performed to monitor disease progression over time. These include the Schober’s test (measuring lumbar flexion distance at the level of L5), occiput-to-wall (measuring cervical neck extension), lateral spine side flexion, thoracic chest expansion, and hip internal rotation. Enthesitis is a hallmark of SpA, and there are multiple sites of ligament and tendon insertions that can be evaluated, but most commonly the Achilles tendon insertion of at the heel is assessed. There are multiple validated enthesitis indices from the Berlin Enthesitis Index (BEI), Masstricht AS Enthesitis Score (MASES), and Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC) that can be performed [12]. A full peripheral joint exam should be performed to assess for tenderness, effusions, warmth, and limitation of range of motion as well as evidence of dactylitis in the fingers or toes.

A full physical exam should additionally be conducted to evaluate for extra-articular manifestations. This should include a thorough skin evaluation to look for signs of psoriasis along extensor surfaces, behind ears, in the umbilicus, and within the crease of the buttocks; evaluation for signs of gastrointestinal or sexually transmitted diseases; and evaluation for SpA comorbidities such as cardiovascular and respiratory disease.

Lab Testing

There are no diagnostic labs for SpA. Common lab tests include HLA-B27 and acute phase reactants such as ESR or CRP, which may serve to support clinical suspicion. It is important to note that the absence of these does not rule out SpA. Additional tests may be ordered related to details of the history and physical exam, such as fecal calprotectin or sexually transmitted infection testing if considering IBD-associated SpA or reactive arthritis, respectively. All patients need to be assessed for blood cell counts, liver and kidney function, hepatitis and HIV screening, and TB screening depending upon their treatment plan.

Imaging

X-rays are the first-line imaging modality, which can demonstrate SI joint abnormalities ranging from blurring of the joint margins to evidence of sclerosis and erosions and ultimately with complete joint fusion. These images can also be obtained using the Ferguson view, entailing a 20-degree caudocephalic AP X-ray. The findings are usually bilateral in SpA, and unilateral findings should prompt one to consider alternative diagnoses. Spinal X-rays in AS can demonstrate vertebral body squaring, shiny corner sign (small erosions at the corners of the vertebral bodies), ossification of spinal ligaments/discs, enthesophytes, and progressive bamboo spine. Peripheral joint X-rays are more variable and may not always demonstrate abnormality. However, in PsA, X-rays in established disease often demonstrate erosive disease, particularly in the hands and feet in which the classic pencil-in-cup appearance of IP joints can be observed.

MRI can also be performed in the appropriate clinical setting, such as a high suspicion for axial SpA in the setting of normal X-rays but a suspicious clinical history. The most appropriate MRI sequences to identify SI joint inflammation are T1 and STIR. MRI findings will demonstrate synovial enhancement and increased STIR signal representing edema during acute inflammation and increased T1 signal representing bone marrow metaplasia suggesting past inflammation.

Imaging can also be useful for monitoring progression over time or to determine changes in therapy. For example, a patient with AS may complain of continued back pain while on therapy, and X-rays have not changed in the past several years. In this case an MRI can help determine if features of joint inflammation are present to warrant therapy changes.

Differential Diagnosis

Based upon the appropriate workup, an appropriate differential diagnosis must be considered that includes both inflammatory and noninflammatory disorders. Other disease processes to consider include the following: mechanical back pain, osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH), iliac condensans ilii, Paget’s disease, Brucellosis, Whipple’s disease, SI joint infection, gout, and osteochondrosis.

Treatment

The 2016 SPARTAN/GRAPPA recommendations for the management of axial SpA support use of physical therapy for all patients. NSAIDs are recommended as first-line therapy, followed by TNF-inhibitors and then alternate biologic agents [13]. Specific agents and uses are discussed below.

NSAIDs

The first line of therapy for all SpAs is scheduled high-dose NSAIDs. After the initial diagnosis of axial SpA, the treatment requires a minimum of two separate NSAIDs at maximum dosage for a total of 2–4 weeks each before escalation of therapy. Consideration must be taken with other comorbidities such as coronary artery disease and chronic kidney disease and the risk of long-term NSAID usage. NSAIDs have demonstrated an ASAS20 (20% partial response) rate of >70% and ASAS40 (40% partial response) rate of >50% in patients that start with an NSAID [14].

Conventional Synthetic DMARDs

Conventional synthetic DMARDs are generally ineffective in the setting of axial disease, but can be beneficial in peripheral joint symptoms. Sulfasalazine has demonstrated some efficacy in the setting of peripheral arthritis and decreased inflammatory markers, with no evidence for benefit in spinal mobility, patient/physician assessment, or enthesitis [15]. Methotrexate has been found to have similar lack of efficacy with regard to axial symptoms but also found to have lack of efficacy for peripheral joint symptoms in AS [16]. For PsA, though, the csDMARDs methotrexate, sulfasalazine, leflunomide, and cyclosporin all have demonstrated efficacy for arthritis and varying results for skin [17].

Biologic DMARDs

There are a number of biologic medications that have been FDA approved for SpA or are under investigation. Table 8.2 summarizes currently approved medications, targets, and indications. TNF-alpha inhibitors such as infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab are first-line biologic therapies and highly effective. The number needed to treat to achieve partial remission is between 2.3 and 6.5 [18]. Whether TNF-inhibitors halt radiographic progression remains a question; overall, they may not have a significant impact, but early (within 5 years of disease onset) and sustained use may reduce progression [19]. Etanercept has less clinical efficacy in the setting of GI symptoms and uveitis [20]. The most significant contraindications to TNF-inhibitor therapy include active infection (including latent or active tuberculosis), advanced heart failure, systemic lupus erythematosus, and multiple sclerosis.

Newer FDA-approved biologics target the Th17 pathway. The side effect profile of these agents is similar to TNF-inhibitors. There is some caution advised for use of IL-17 inhibitors in individuals with IBD as there is rare occurrence of developing IBD while on the drug and the phase II trial of secukinumab in Crohn’s disease demonstrated worsening of bowel inflammation [21].

Abatacept acts on T-cell costimulation and is currently approved for PsA. Abatacept prevents CD28 from binding to CD80/CD86. The side effect profile of abatacept is similar to TNF-alpha inhibitors.

Target-Specific DMARDs

Apremilast is a newly approved medication that is indicated for PsA. The mechanism of action involves inhibition of phosphodiesterase-4. Clinical efficacy has been shown in multiple clinical trials, and it is recommended not to be used in combination with other biologic medications.

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are currently also being investigated for use in the treatment of SpA. Thus far tofacitinib has been approved for PsA with numerous others currently in the clinical trial phase. Clinical trials have shown tofacitinib to be comparable in efficacy to TNF-alpha inhibitors.

Other Treatments

Other important treatment modalities for patients with SpA include physical therapy (PT), intra-articular steroid injections, and possible surgical interventions to help with pain and quality of life. Physical therapy has a large role in the management of pain and physical function. Cochrane review data shows that an individual home based or supervised exercise program is better than no intervention, supervised PT is better than home exercise, and spa-exercise therapy with PT is better than PT alone [22]. Intra-articular injections can be beneficial in the management of isolated inflamed joints, including SI joints, and systemic steroids can have a role in peripheral disease (ineffective in axial disease). It is generally advised to avoid any type of surgery in axial SpA except for emergent situations due to risk of severe fracture.

Disease Monitoring

Regular follow-up is recommended to assess disease activity and determine whether a change in therapy is indicated. Clinically, the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) can be utilized (Table 8.3) [23]. A thorough history and exam should be performed at each visit and imaging considered. The clinical measurements that are listed above in the examination section such as Schober’s test and occiput-to-wall measurements can be performed and help guide therapy. The combination of patient reported symptoms, physical exam findings (including measurements), lab data, and imaging can all help to guide therapy and decide whether or not an escalation or change in therapy is warranted.

Comorbidities

There are a number of relevant comorbidities in patients that have SpA, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), obesity, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, ophthalmic disease, malignancy (lymphoma), restrictive lung disease, liver/kidney disease, and depression/anxiety. Cardiovascular disease has an incidence between 3.3% and 9.6% in patients with PsA [24], and a hazard ratio of 1.41 relative to matched controls in AS [25]. The rheumatologist should help manage cardiovascular risk in conjunction with the Primary Care Physician. EULAR recommendations for CVD management include optimally controlling rheumatologic risk and using NSAIDs with caution. Basic screening should be performed with regard to monitoring blood pressure, monitoring lipids, and counseling on smoking cessation. Other relevant screening should be performed such as monitoring for obesity with appropriate counseling, monitoring fasting blood glucose or hemoglobin A1C, monitoring liver and kidney labs, and monitoring for symptoms regarding eye or GI involvement of disease.

Prognosis

Overall outcomes are generally good for SpA if diagnosed and treated in an appropriate amount of time; however, up to 30% of patients with SpA will be on disability 20 years after diagnosis [26]. Earlier diagnoses usually manifest as undifferentiated SpA, which carries a 40% progression rate to diagnosed AS [27]. Patients with SpA are at high risk of bone fracture, and require close monitoring for bone health, as well as an ongoing need for physical and occupational therapy. Trauma is also a concern in these patients, as the higher rate of spinal fracture can lead to neurologic emergencies such as spinal cord impingement or cauda equina syndrome.

Questions

-

1.

A 45-year-old man with known psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis presents to clinic with worsening skin plaques. Symptoms were previously well controlled on Etanercept. The patient reports abrupt worsening of plaques diffusely across his trunk, elbows, and knees.

On examination, the patient has a temperature of 100.8 degrees Fahrenheit and is hemodynamically stable. Synovitis is noted diffusely throughout the bilateral PIPs, DIPs, wrists, knees, and ankles. Skin plaques are noted diffusely throughout the aforementioned areas.

What is the next appropriate step in the management of this patient?

-

A.

HIV testing

-

B.

HLA-B27 testing

-

C.

Blood cultures and empiric antibiotics

-

D.

Switch etanercept to adalimumab

Correct answer: A

Explanation: This question addresses the concerning situation of rapidly progressive, widespread psoriasis in the setting of HIV infection. A patient who is well controlled on current therapy with a rapid progression of psoriasis (and psoriatic arthritis) warrants evaluation for HIV. There is no indication to check HLA-B27 (choice B) as this patient has known Pso/PsA and a positive HLA-B27 would not change management. There does not appear to be a systemic bacterial infection despite the mild fevers, and this patient is otherwise stable. Diffuse joint pain with synovitis is unlikely to be infectious. Thus, there is no indication for blood cultures and empiric antibiotics (choice C). A change in therapy could be considered if there were an insidious worsening of symptoms, but this question stems around a more rapid, abrupt progression in symptoms. There is no indication to change medication management at this point (choice D).

-

A.

-

2.

A 22-year-old woman presents to clinic with worsening low back pain. Her symptoms are worse in the morning, and she describes approximately 1 hour of low back stiffness that resolves with ambulation. She also describes symmetric buttock pain without radiation to her legs. There is no history of trauma. Over-the-counter ibuprofen has helped somewhat with pain control.

On examination, vital signs are normal. There is tenderness to palpation in both sacroiliac joints. Range of motion testing is normal. There is no evidence of peripheral arthritis or skin rash. X-rays of the lumbar spine and sacroiliac joints are unremarkable. ESR is elevated to 60 mm/hour, and HLA-B27 is positive.

What is the next step in obtaining a diagnosis?

-

A.

No further testing is required.

-

B.

MRI of lumbar spine and SI joints.

-

C.

RF and CCP.

-

D.

CRP.

Correct answer: B

Explanation: This question is describing a patient with inflammatory low back pain: morning stiffness that improves with ambulation and buttock pain without radiation into the legs are significant clues. Exam findings of bilateral SI joint tenderness, elevated inflammatory markers and positive HLA-B27 are consistent with the clinical suspicion for SpA. X-rays do not demonstrate any abnormalities in the lumbar spine or SI joint. The next best step would be MRI of the lumbar spine and SI joints (choice B) to confirm axial inflammation. MRI is a better imaging modality and can detect early SI joint inflammation before X-ray findings are apparent. There is no indication to check RF and CCP (choice C), as the patient’s symptoms are more concerning for SpA than rheumatoid arthritis. CRP (choice D) would not change management. MRI would be the next appropriate step for diagnosis verification rather than presumption (choice A).

-

A.

-

3.

A 22-year-old man presents to clinic with 2 weeks of worsening bilateral ankle pain. He reports that his pain is worse in the morning when he wakes up, and generally lasts for approximately 45 minutes. He reports no other joint symptoms or rashes. He has a history of Clostridium difficile infection approximately 5 weeks ago that was successfully treated with oral vancomycin. There has been no further diarrhea or gastrointestinal symptoms. No recent sexual contacts.

On examination, vital signs are normal. There is redness, warmth, and swelling of the bilateral ankles. The remainder of the physical exam is normal. Labs reveal an elevated ESR to 46 mm/hour. X-rays of both ankles are normal.

What is the next step in the management of this patient?

-

A.

Joint aspiration

-

B.

Gonorrhea and chlamydia testing

-

C.

RF and CCP

-

D.

No further workup

Correct answer: D

Explanation: A young healthy male with lower extremity inflammatory oligoarthritis is concerning for reactive arthritis in the setting of recent GI infection. This patient describes inflammatory arthritis symptoms 5 weeks after C. difficile infection. While his GI symptoms are improving, arthritis has now developed. Both ankles have effusions and inflammatory markers are elevated. Reactive arthritis is a clinical diagnosis in the appropriate setting, such as this patient with recent GI infection. It is unlikely to have bilateral septic or crystalline arthritis so there is no indication for aspiration (choice A). He has no recent sexual contacts and no GU symptoms, so there is no indication for STI testing (choice B), although gonococcal arthritis can present similarly. While acute lower extremity inflammatory arthritis could possibly be rheumatoid arthritis (choice C), this is less likely in the clinical context and would not be a classic presentation. There is no indication for further workup, and conservative management (NSAIDs) is appropriate.

-

A.

-

4.

A 31-year-old woman is diagnosed with non-radiographic SpA. She is initially started on high-dose NSAID treatment for 1 month and changed to a different NSAID 1 month later due to lack of efficacy and continued low back pain. At a follow-up visit 1 month following initiation of the second NSAID, she continues to report approximately 1 hour of morning stiffness with significant bilateral SI joint tenderness on examination. She reports no peripheral joint symptoms, and no eye or gastrointestinal symptoms.

What is the next therapeutic step in the management of this patient?

-

A.

Start methotrexate.

-

B.

Start certolizumab.

-

C.

Continue NSAIDs.

-

D.

Start ustekinumab.

Correct answer: B

Explanation: Non-radiographic SpA is a clinical diagnosis in which classical X-ray findings are absent but the MRI demonstrates inflammation. She has failed an appropriate trial of two separate NSAIDs, and it is time to start a biologic medication (choice B) according to SPARTAN-SAA-GRAPPA guidelines. Methotrexate is helpful with peripheral joint symptoms, but does not help axial symptoms (choice A). It would not be appropriate to continue NSAIDs at this point as this patient has already failed two separate therapeutic trials (choice C). She has no contraindications to biologic therapy that are mentioned, and certolizumab would be appropriate as an approved TNF-inhibitor for nr-SpA. Ustekinumab is currently FDA approved for psoriatic arthritis, and not for nr-SpA (choice D).

-

A.

-

5.

A 62-year-old man with ankylosing spondylitis is involved in a motor vehicle accident. On evaluation by EMS the patient is having mild symmetric weakness in his bilateral legs. There is no loss of urine or stool. Vital signs are stable.

The patient has an extensive history of ankylosing spondylitis with near complete fusion of his lumbar spine. He has remained on adalimumab for many years without complications. He has required a walker for ambulation due to significant back disease.

The patient is stabilized in the field and transported to the nearest trauma center. What is the next step in evaluation of this patient?

-

A.

EMG

-

B.

Spine MRI

-

C.

Physical therapy

-

D.

Emergent neurosurgery evaluation

Correct answer: D

Explanation: This patient has advanced AS with spinal fusion. He was involved with a motor vehicle accident, and his complaints of mild symmetric leg weakness are very concerning for spinal fracture. Patients with SpA are higher risk for fracture, and this patient has symptoms associated with spinal cord damage. This requires emergent neurosurgical evaluation for repair (choice D). Spine MRI (choice B) or CT will need to be considered at some point on arrival to a trauma center, but the lower extremity weakness needs to be evaluated for emergent surgery. After further workup, it could be reasonable to consider EMG (choice A) or physical therapy (choice C) if this was found to not be a surgical process.

-

A.

-

6.

A 66-year-old woman presents with worsening lower back pain over the past 5 years. She reports having approximately 1 hour of morning stiffness daily. High-dose ibuprofen was tried by her primary care provider with some improvement in symptoms. Laboratory data demonstrate a positive HLA-B27.

X-rays are notable for SI joint sclerosis along the ileal margin and small osteophytes at the inferior aspects bilaterally. There are no erosions, joint space narrowing, or subchondral sclerosis.

Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

-

A.

Ankylosing spondylitis

-

B.

Osteitis condensans ilii

-

C.

Osteoarthritis

-

D.

Psoriatic arthritis

Correct answer: B

Explanation: Osteitis condensans ilii is a mimic of SpA caused by sclerosis of the ileal bone next to the SI joints, usually in a triangular pattern on X-rays. This causes SI joint pain that can present similar to SpA. This 66 year old female with 5 years of low back pain is unlikely to be classified with axial SpA at the age of 61 (choice A) per ASAS criteria. While this could be osteoarthritis (choice C), the presence of ileal sclerosis on X-rays indicates osteitis condensans ilii (choice B) as the more likely cause. This is unlikely to be psoriatic arthritis given only axial involvement with no evidence of skin psoriasis (choice D).

-

A.

-

7.

A 78-year-old man presents to his PCP with worsening back pain. The patient reports the symptoms have been worsening over the past year. Pain is diffuse throughout the spine, causing significantly decreased range of motion and mobility. The symptoms have no temporal relation, and acetaminophen causes some relief.

On examination, vital signs are normal. There is bilateral bony hypertrophy of both knees with crepitus. There is minimal tenderness to palpation along the spine. Decreased range of motion is present throughout the thoracic and lumbar spine, with pain on extension and flexion.

X-rays demonstrate contiguous osteophytes from T12-L4. Sacroiliac joints are patent with no evidence of sclerosis. There is no spinal canal narrowing or notable degenerative disease.

What is the most likely diagnosis?

-

A.

Osteoarthritis

-

B.

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

-

C.

Ankylosing spondylitis

-

D.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Correct answer: B

Explanation: This patient presents with diffuse back pain that is noninflammatory in nature. There is decreased range of motion throughout the spine. X-rays show contiguous osteophytes from T12-L4, which is a finding associated with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH, choice B). DISH is a disorder identified by abnormal calcification and bone formation throughout the anterior longitudinal ligament in a continuous pattern of multiple vertebrae and occurs more often on the right side. These presenting symptoms could be due to osteoarthritis, but with diffuse pain and X-rays lacking evidence of degenerative disease, it would be unlikely to have such significant symptoms (choice A). Ankylosing spondylitis is unlikely given the patient’s age, lack of predominant low back symptoms, and noninflammatory presentation (choice C). Rheumatoid arthritis is unlikely to present with isolated back pain with no peripheral involvement, as well as a lack of inflammatory symptoms (choice D).

-

A.

-

8.

What is the mechanism of action of secukinumab?

-

A.

IL-12/23 inhibition

-

B.

TNF-alpha inhibition

-

C.

T-cell costimulation inhibition

-

D.

IL-17A inhibition

Correct answer: D

Explanation: Secukinumab is an IL-17A inhibitor (choice D). It is currently FDA approved for psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Ustekinumab is another interleukin inhibitor that acts on IL-12/23 (choice A), and is currently approved for psoriatic arthritis. Numerous TNF-inhibitors (choice B) are approved for multiple indications related to SpA. Abatacept acts on T-cell costimulation by preventing CD28 from binding to CD80/CD86 (choice C).

-

A.

-

9.

A 54-year-old man with known PsA and psoriasis presents for follow-up. He has previously been on adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, secukinumab, and methotrexate, which were stopped due to adverse reactions or loss of efficacy. The patient is currently experiencing worsening joint pain throughout, as well as worsening plaque psoriasis compared to last visit. A decision is made to start tofacitinib.

In addition to a blood cell counts and liver and kidney function, which of the following must be monitored while on tofacitinib?

-

A.

Hemoglobin A1C

-

B.

Lipid panel

-

C.

Pulmonary function tests

-

D.

Creatinine

Correct answer: B

Explanation: This patient has psoriatic arthritis with significant disease that has been difficult to manage. He has failed csDMARD therapy, as well as three TNF-inhibitors and one IL-17A inhibitor. Thus, the plan is to start JAK kinase inhibitor, tofacitinib. One potential side effect of tofacitinib is elevated cholesterol, which must be monitored at baseline, 4–8 weeks after initiation of tofacitinib, and then every 3 months (choice B). If cholesterol levels rise, a statin should be initiated based upon ASCVD risk guidelines. Tofacitinib has no known effect on hemoglobin A1C (choice A), and monitoring should be based on patient risk factors for diabetes. There is no noted chronic pulmonary side effects related to tofacitinib (besides increased infection risk), and there is no indication for monitoring pulmonary function tests (choice C). There is no significant effect on kidney function while on tofacitinib (choice D).

-

A.

-

10.

A 47-year-old man with ankylosing spondylitis presents to his Primary Care Physician’s office for a routine physical. He has not seen his PCP in multiple years. He also has a history of GERD and osteoarthritis. For his ankylosing spondylitis, his symptoms have been well controlled on Etanercept for many years.

Which of the following is the most important screening measure?

-

A.

Depression screen

-

B.

Colonoscopy

-

C.

Lipid panel

-

D.

DEXA scan

Correct answer: C

Explanation: Patients with a history of SpA have an increased risk for cardiovascular disease. Appropriate screening and monitoring must be performed to help minimize cardiovascular risk factors. While this 47 year old male does not have traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease (coronary artery disease, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, etc.), his history of ankylosing spondylitis puts him at increased risk. He has not had a physical with blood work in years, and the most appropriate screening would be a lipid panel (choice C) to stratify risk and determine if statin therapy is indicated. There is no physiologic reason for a depression screen (choice A) beyond routine primary care practices. A colonoscopy (choice B) is not indicated until the age of 50 unless there is a history of colon cancer in a first-degree relative or the patient is experiencing GI symptoms (diarrhea, hematochezia, etc.). There is no indication for DEXA screening (choice D) in this 47-year-old male that does not appear to have a history of risk factors for osteoporosis.

-

A.

-

11.

A 54-year-old man with ankylosing spondylitis presents for routine follow-up with his rheumatologist. His joint symptoms are currently well controlled on adalimumab monotherapy. Routine labs are unremarkable.

Which of the following should be addressed in an appropriate review of systems?

-

A.

Eye pain or redness

-

B.

Pain in the Achille’s tendons

-

C.

Changes in bowel habits

-

D.

All of the above

Correct answer: D

Explanation: SpA is a spectrum of disease, and numerous extra-articular manifestations can occur. This male currently has well-controlled ankylosing spondylitis, but it is important to assess for the development of comorbidities. An appropriate review of systems includes questions screening for uveitis (choice A), enthesitis (choice B), IBD-associated symptoms (choice C), as well as other comorbidities such as CVD, obesity, diabetes, dyspnea, and depression

-

A.

-

12.

A 64-year-old man with PsA presents for follow-up several months after being his initial diagnosis. He has failed naproxen and meloxicam with appropriate length trials. On examination, he has diffuse psoriatic plaques and synovitis in his DIPs and PIPs. His other comorbidities include well-controlled type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease, and heart failure with an ejection fraction of 25%.

Which of the following is the most appropriate therapeutic to prescribe?

-

A.

Adalimumab

-

B.

Secukinumab

-

C.

Indomethacin

-

D.

Etanercept

Correct answer: B

Explanation: This patient is presenting for follow-up evaluation after an appropriate trial of two separate NSAIDs and still presenting with active psoriatic arthritis. The next most appropriate step at this point is to escalate therapy to a biologic medication. It would not be appropriate to prescribe a third NSAID (choice C) due to already failing two other NSAIDs. When choosing an appropriate biologic therapy, it is important to consider other medical comorbidities that could complicate treatment. This patient has systolic heart failure with an ejection fraction of 25%, and there is a relative contraindication to TNF-inhibitors in the setting of advanced heart failure (choice A and D). Interleukin inhibitors such as secukinumab (choice B), ustekinumab, and ixekizumab are approved for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis, and would represent appropriate therapeutic options.

-

A.

-

13.

A 24-year-old woman presents for evaluation of persistent low back pain for the past 4 months. Symptoms are worse in the morning and result in approximately 90 minutes of morning stiffness. Nothing makes symptoms better or worse. Labs are remarkable for a normal ESR and CRP, and a negative HLA-B27. On examination the patient is nontoxic appearing, and there is tenderness to palpation in the bilateral SI joints. X-ray is obtained using the Ferguson view with normal appearing SI joints. MRI is ordered and demonstrated below.

What is the most likely diagnosis?

-

A.

Mechanical back pain

-

B.

Osteitis condensans ilii

-

C.

Ankylosing spondylitis

-

D.

SI joint infection

Correct answer: C

Explanation: This woman’s clinical presentation with a 4-month history of inflammatory back pain is concerning for axial SpA. Laboratory testing is uninformative; ESR and CRP are infrequently elevated in SpA. The X-ray is unremarkable for any SI joint involvement, but an MRI is ordered to aid in diagnosis given the presence of inflammatory back pain. The MRI image is from a STIR sequence and demonstrates bilateral SI joint bone marrow edema, left side greater than right, suggestive of inflammation. The most likely diagnosis overall is ankylosing spondylitis (choice C). It is unlikely that this patient has simple mechanical back pain (choice A) as the presenting symptoms are inflammatory in nature and the MRI demonstrates SI joint inflammation. Osteitis condensans ilii is a mimic of ankylosing spondylitis, but tends to occur in older females who are multiparous and have a triangular pattern on imaging. There is nothing in the question stem that would be concerning for SI joint infection (choice D), and the MRI makes it unlikely given the bilateral involvement of the SI joints.

-

A.

-

14.

A 54-year-old man presents to rheumatology with a complaint of back pain for the past 3 months. His pain is worse in the morning, with approximately 20–30 minutes of morning stiffness. He also has occasional arthralgias in the hands, knees, and ankles. Two weeks ago, the patient developed intermittent diarrhea and abdominal pain. The diarrhea is described as watery, without evidence of blood or mucus. He has lost approximately 8 pounds in the past week.

On examination, he is nontoxic appearing with normal vital signs. There are multiple tender joints, but no synovitis. There is no tenderness to palpation in the bilateral SI joints.

Lab results demonstrate evidence of an elevated ESR and CRP. HLA-B27 is negative. RF and CCP are negative. X-rays are performed and demonstrate no peripheral erosions and no evidence of SI joint inflammation.

Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

-

A.

Ankylosing spondylitis

-

B.

Seronegative RA

-

C.

IBD-associated SpA

-

D.

Whipple’s disease

Correct answer: D

Explanation: This patient presents with low back pain and oligoarthritis for the past 3 months associated with watery diarrhea for 2 weeks and weight loss. The examination is notable for no synovitis and no tenderness in the SI joints despite it being the main presenting complaint. Laboratory workup is remarkable only for elevated inflammatory markers, and X-rays demonstrate no evidence of inflammatory arthritis or SpA. This question introduces a rare mimic of SpA (and other inflammatory arthridites), and is meant to be a case of Whipple’s disease (choice D). Whipple’s disease caused by Tropheryma whipplei can mimic SpA and rheumatoid arthritis. This is unlikely to be ankylosing spondylitis (choice A) given the age of the patient. This could potentially be seronegative RA (choice B), although the absence of synovitis on exam argues otherwise; however, the diarrhea and weight loss are clues that there may be another etiology. It would be unusual for this to be a presentation of IBD-associated SpA (choice C) given the lack of inflammatory symptoms and the presence of watery diarrhea, but it should be considered on the differential.

-

A.

-

15.

A 30 year-old man with HLA-B27+ AS returns to your office for follow-up of his disease. He has been on golimumab since his diagnosis nearly 10 years ago and states that he is feeling well. His exam is unchanged and BASDAI is 1. He recently got married and asks regarding the risk of his children having this disease. Which of the following are true?

-

A.

40% of individuals with the presence of an HLA-B27 allele and a first-degree relative will develop AS.

-

B.

Male children will have an increased risk of AS compared to his female children.

-

C.

Additional genes such as NOD2 (CARD15) increase the risk of developing AS.

-

D.

All of the above.

Correct answer: A

Explanation: The question of disease inheritance is fairly common among patients with rheumatologic disease. Genetic studies have shown the strongest linkage between HLA-B27 and AS. Epidemiologic studies have shown that then incidence of HLA-B27 to be present in the overwhelming majority of cases, but only ~5% of individuals with this gene develop disease. The presence of HLA-B27 and a first-degree relative with AS increases the incidence of disease to 40% (choice A). Although, interestingly, there is an increased risk of AS if one’s mother had disease compared to one’s father, there is no difference in risk of AS between male and female offspring (option B). While there are overlapping genetic risk loci between IBD and AS, NOD2/CARD15 is unique to Crohn’s disease (choice C). Shared genetic risk loci between IBD and AS lie within the IL-17, IL-23, and TNF pathways.

-

A.

References

Zochling J, Smith EU. Seronegative spondyloarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24(6):747–56.

Kehl AS, Corr M, Weisman MH. Review: enthesitis: new insights into pathogenesis, diagnostic modalities, and treatment. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(2):312–22.

Braun J, Sieper J. Ankylosing spondylitis. Lancet. 2007;369(9570):1379–90.

Smith JA. Update on ankylosing spondylitis: current concepts in pathogenesis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15(1):489.

Reveille JD. Genetics of spondyloarthritis--beyond the MHC. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8(5):296–304.

Jethwa H, Abraham S. The evidence for microbiome manipulation in inflammatory arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(9):1452–60.

Reveille JD, Witter JP, Weisman MH. Prevalence of axial spondylarthritis in the United States: estimates from a cross-sectional survey. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(6):905–10.

Carter ET, McKenna CH, Brian DD, Kurland LT. Epidemiology of ankylosing spondylitis in Rochester, Minnesota, 1935-1973. Arthritis Rheum. 1979;22(4):365–70.

Dean LE, Jones GT, MacDonald AG, Downham C, Sturrock RD, Macfarlane GJ. Global prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53(4):650–7.

Stolwijk C, Boonen A, van Tubergen A, Reveille JD. Epidemiology of spondyloarthritis. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2012;38(3):441–76.

Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, Listing J, Akkoc N, Brandt J, et al. The development of assessment of spondyloArthritis international society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):777–83.

Mease PJ, Van den Bosch F, Sieper J, Xia Y, Pangan AL, Song IH. Performance of 3 enthesitis indices in patients with peripheral spondyloarthritis during treatment with adalimumab. J Rheumatol. 2017;44(5):599–608.

Ward MM, Deodhar A, Akl EA, Lui A, Ermann J, Gensler LS, et al. American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis research and treatment network 2015 recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(2):282–98.

Sieper J, Lenaerts J, Wollenhaupt J, Rudwaleit M, Mazurov VI, Myasoutova L, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab plus naproxen versus naproxen alone in patients with early, active axial spondyloarthritis: results from the double-blind, placebo-controlled INFAST study, part 1. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):101–7.

Chen J, Liu C. Sulfasalazine for ankylosing spondylitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD004800.

Chen J, Veras MM, Liu C, Lin J. Methotrexate for ankylosing spondylitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD004524.

Ash Z, Gaujoux-Viala C, Gossec L, Hensor EM, FitzGerald O, Winthrop K, et al. A systematic literature review of drug therapies for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis: current evidence and meta-analysis informing the EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(3):319–26.

Baraliakos X, van den Berg R, Braun J, van der Heijde D. Update of the literature review on treatment with biologics as a basis for the first update of the ASAS/EULAR management recommendations of ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51(8):1378–87.

Haroon N, Inman RD, Learch TJ, Weisman MH, Lee M, Rahbar MH, et al. The impact of tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors on radiographic progression in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(10):2645–54.

Guillot X, Prati C, Sondag M, Wendling D. Etanercept for treating axial spondyloarthritis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2017;17(9):1173–81.

Hueber W, Sands BE, Lewitzky S, Vandemeulebroecke M, Reinisch W, Higgins PD, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibody, for moderate to severe Crohn’s disease: unexpected results of a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Gut. 2012;61(12):1693–700.

Dagfinrud H, Kvien TK, Hagen KB. Physiotherapy interventions for ankylosing spondylitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;1:CD002822.

Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index. J Rheumatol. 1994;21(12):2286–91.

Husni ME. Comorbidities in psoriatic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2015;41(4):677–98.

Walsh JA, Song X, Kim G, Park Y. Evaluation of the comorbidity burden in patients with ankylosing spondylitis using a large US administrative claims data set. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37(7):1869–78.

Osterhaus JT, Purcaru O. Discriminant validity, responsiveness and reliability of the arthritis-specific work productivity survey assessing workplace and household productivity within and outside the home in patients with axial spondyloarthritis, including nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16(4):R164.

Xia Q, Fan D, Yang X, Li X, Zhang X, Wang M, et al. Progression rate of ankylosing spondylitis in patients with undifferentiated spondyloarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(4):e5960.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Berlinberg, A., Kuhn, K.A. (2020). Axial Spondyloarthritis. In: Efthimiou, P. (eds) Absolute Rheumatology Review. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23022-7_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23022-7_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-23021-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-23022-7

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)