Abstract

This chapter analyzes aspects of higher education in the contemporary world. It is particularly concerned with aspects of globalization and internationalization. The focus of the chapter highlights various approaches that reveal such aspects in different contexts. The chapter provides an overview of the field of higher education policies and recent reforms in a range of different countries and continents while developing an understanding of the importance of comparative studies in terms of policies and practices related to higher education in a range of different scenarios. Throughout the presentation of the chapters, there is a synthesis of the themes that emerge in the current debates covered in this book.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

This chapter analyzes aspects of higher education in the contemporary world. It is particularly concerned with aspects of globalization and internationalization. The focus of the chapter highlights various approaches that reveal such aspects in different contexts. The chapter provides an overview of the field of higher education policies and recent reforms in a range of different countries and continents while developing an understanding of the importance of comparative studies in terms of policies and practices related to higher education in a range of different scenarios. Throughout the presentation of the chapters, there is a synthesis of the themes that emerge in the current debates covered in this book.

Higher Education Policies and Recent Reforms

Martin Trow’s seminal text of 1972, in which he considered the transformation of the university sector, based its evolutionary position on a single factor, the institutional evolution implied by an increase in the number of pupils enrolling. Considering the international environment of the time, it is only necessary to evoke the consequences of the Vietnam War and the attitude of the American youth. Nothing has so far been written relating to the economic and social developments that are fast approaching the world of the future.

Today, there are innumerable analyses that put into perspective the transformations universities across the world are undergoing. The intensity of speed of transformations the world is currently undergoing would once have seemed unimaginable. The ease of material and immaterial exchanges, through the development of both physical and digital means of communication, and the strengthening of international economic competition, has seen the appearance of new national actors, in particular BRICS, as well as such economic factors as GAFA. This competition, increasingly focusing on research and innovation, creates a context that heightens the demands of higher education and often leads to a significant change in its modes of action and internal organization. These global developments go well beyond the impact on universities’ internationalization policy. They influence the whole functioning of the university sector globally.

Probably, one of the most influential forces on higher education has been the way the world of work has changed in recent years, with the emergence of a knowledge society. The term knowledge society has been coined to indicate not only the expansion of participation in higher education or of knowledge-intensive or high-technology sectors of the economy, but rather a situation in which the characteristics of work organizations across the board change under the influence of an increasing importance of knowledge (Drucker 1959). It can be considered, according to Foray (2000), that the knowledge economy is at the confluence of two main evolutions: the growing importance of human capital activities and the development of information and communication technologies. As argued by Castells (2000) a global economy is something different than a world economy, as taught by Fernand Braudel and Immanuel Wallerstein. It is an economy with the capacity to work as a unit in real time on a planetary scale (Giddens 1990). It is only in the late twentieth century that the world economy was able to become truly global, based on the new infrastructure provided by information and communication technologies.

Obviously, higher education is affected by this radical evolution as well as actors. Some also question the role of the university as an agent of globalization (Sehoole and Knight 2013; Jane Knight 2008).

Transformations are numerous and affect, apart from aspects related to globalization, at least four domains (Salmi 2002, 2017):

-

Changing training and needs (lifelong learning of working adults and new modes of teaching and learning).

-

New forms of competition (through distance teaching between local universities, or from universities abroad, networks of universities, and corporate universities for profit-providers).

-

New forms of accountability (such as quality assurance agencies and global rankings) and changes in structures and modes of operation.

-

New disciplines meaning new departments or reorganization of old departments, use of innovative technology, Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), and open-education resources.

These transformations are the result of tensions between the global and the local, between the autonomous identity of the institution and the requirements of external authority (Marginson 2011a; Beck 2012). Even if the power of the national States diminishes, because of budgetary support they are still able to mobilize (Kwieck 2001), traditions and peculiarities of national systems produce path dependencies that sustain cross-national variation (Bleiklie 2005). It is obvious however, that some universities remain reluctant to change (Salmi 2002).

Nevertheless, the international dimension is undoubtedly one of the factors that has most influenced the evolution of higher education in the last 20 years. This may be evidenced and illustrated by the esteemed position held by international rankings. Such rankings are now in the minds of governments, university managers, and students and their families (Hazelkorn 2015; Wihlborg and Robson 2018). The promotion of models of higher education, whether by international agencies (WB, OECD, and UNESCO) or in the framework of agreements between governments, like through the Bologna Process, does not, however, lead to a standardization of structures. In the context of European Higher Education Areas (EHEAs), different countries implement policies selectively and at different levels, depending on their national higher education context (Klemenčič 2018).

Internationalization, like the ideological vision promoting more “internationality,” has become the motto of many transformations, based on the crossing of borders, in particular by students (Teichler 2017), into and toward developed countries. Such a situation is also evolving between developing countries, as evidenced in Africa (Tamrat 2018), Latin America (Nitz 2017), and Asia (Chan 2012).

The internationalization of universities may be a competitive strategy operating between universities (Beck 2012), however, its reality needs to be approached with caution because the results of internationalization can sometimes fall below expectation (Noorda 2014), carrying with it misconceptions (De Wit 2017). It can also lead to an increased differentiation between universities, between top universities and low, underfunded ones (Marginson 2016). Additionally, such differentiation may become an agent against political, ideological, and religious struggles in the modern world (Altbach and De Wit 2017).

The increasing instrumentalization of universities in national strategies of international economic competition should not overshadow the humanist dimension of higher education—developing the full potential of students (Salmi 2002). Social engagement is the most notable activity in Latin American universities (Mora et al. 2018) and some European universities too (Goddard et al. 2016).

For a long time, comparisons between the evolution of higher education policies and their associated models has only been considered in developed countries, because of the age of their systems and their influence globally, the comprehensive overview by Kaiser et al. (1994) provides a good example. Gradually, universities in developing countries have become objects of analysis, through their institutional responses to changing contexts (Chapman and Austin 2002), or a specific attention to the BRICS (Schwarzman et al. 2015) or to China and India when the changes of universities are at stake (Mihut et al. 2017). African universities are receiving also increasing attention, either through the participation of African economies in economic development (Cloete et al. 2011) or through the role of international higher education as a vehicle for Africa’s current development trajectory (Sehoole and Knight 2013).

However, some call for a mobilization of southern researchers in the development of dedicated research. The last two years of research and development have been dominated by organizations and individuals from the developed world (Jooste and Heleta 2017).

This book intends, from an original comparative approach, to give full voice to the issues associated with the policies and management of higher education in developing countries.

The Importance of Comparative Studies and Cross-Cultural Research in Higher Educational Research

The brief was simple and clear—to jointly edit a book on higher education with colleagues in Brazil and Turkey that would form one volume in a series of books that would adopt the same format. All chapters in this book must include data from at least three different countries, from at least two continents. Another stipulation was that there must be at least one developing country in the mix and that the data collection methodology or instrument must be the same for all countries considered.

Further restrictions were added regarding the length of chapters and the fact that they should derive from original empirical data. The book that you are holding in your hand is the outcome of this endeavor. The contributing authors are from a wide range of countries with vastly different backgrounds, spanning a range of methodological, philosophical, and epistemological traditions. The one thread of commonality between contributing authors is that of a comparative approach to educational research. Precisely what this amounts to is part of an ongoing debate that has often been categorized as having two differing methodological movements. Welch (2011, p. 197 in Markauskaite et al. 2011) refers to:

… the two methodological movements above reveals different assumptions, emphases and omissions between modernist forms (such as survey methodologies measuring educational achievement) and postmodern mapping exercises.

Welch’s chapter clearly outlines the historical nature of comparative education with its emergence from several distinct disciplines including sociology, anthropology, and history.

It quickly became clear to the three joint editors of this collection of studies relating a range of travelers tales from across the world, that not all contributing authors shared the same world view. The observation of Bagnall (2011, p. 203) that “…The ways that people do things throughout the world are not, and, arguably, despite globalisation and its homogenising tendency, never will be the same.” Different regions have different perspectives and always will. The stipulations of the original brief for the nature of the publication have been adhered to but the major unifying thread that runs through all the articles remains the comparative methodology.

Dasen and Akkari (2008, p. 8), in their masterful text Educational Theories and Practices from the Majority World alert us to the need to constantly critique Western ethnocentrism in our writing. “… the role of the king’s fool, pointing out the dominant paradigms and the attractiveness of alternatives, belongs to anthropology of education …” Comparative education sometimes partakes of this endeavor, if it is not confined to government statistics about IPBS systems.

Oforiwaa Gyamera (2017) writing in Hans de Wit et al.’s edited text, The Globalization of Internationalization: Emerging Voices and Perspectives (2017), talked of the positioning that goes on amongst Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) worldwide including those in Ghana. She draws upon an empirical qualitative study on senior management, deans, academics, heads of department, and students. She found that the universities in Ghana were at different stages of development and that older and more established institutions fared better than newer universities. As not a one vice-chancellor said “… internationalization is a ‘do or die affair’ … either you internationalise or you are left behind in the face of globalisation” (Gyamera 2015, p. 112).

Mark Bray notes in his 2014 work Comparative Education Research: Approaches and Methods that the “… nature of any particular comparative study of education depends on the purposes for which it was undertaken and on the identity of the person(s) conducting the enquiry” (Bray 2014, p. 19). In his first chapter he focuses on three distinct groups who undertake comparative studies of education “… policy makers, international agencies, and academics.”

The majority of contributors to this book fall into the academic category provided by Bray. A short biography of those involved in writing the various chapters of the book is provided.

Bray notes that while much is made of borrowing, it is often difficult to substantiate.

From a practical perspective, much of the field of comparative education has been concerned with copying of educational models. Policy makers in one setting commonly seek information about models elsewhere, following which they may imitate those models. (Bray 2014, p. 21)

The point is made by Bray, that once policy makers decide to seek ideas worth copying, they must then decide where to look. According to Bray, they seldom look toward countries that are less developed than themselves. Indeed, when considering the way the OECD developed as a major player in the education arena, there does seem to have been a tradition of looking at successful models in developed economies as potential sources of policy borrowing.

Bray notes the way that policy makers have to decide where to look for ideas worth copying and suggests that a bias exists arising from the language or languages spoken as a major influence, “… policy makers who speak and read English are likely to commence with English-speaking countries, their counterparts who speak and read Arabic are likely to commence with Arabic-speaking countries” (Bray 2014, p. 21).

Academics’ space in comparative research is often occupied by practical assignments that may be similar in nature to those of practitioners and policy makers. This connection may be of a collaborative nature, or as Bray (2014, p. 38) notes “… to highlight ideological and methodological biases.” Often the collaboration between policy makers and practitioners is more of a check and balance than a collaborative venture.

Needless to say, the line between these three different groups of comparativists is a blurred one. Often the theoretical stance proposed by government policy makers is a point of contention for the more practically minded interpreters of the policy, the teachers.

As noted above, the biographical details provided for contributors to this book will enable readers to position the writers within this simple framework provided by Bray and others.

Intercultural Studies in Higher Education: Policy and Practice

The methodological challenges proposed in this book present three major themes:

-

The reforms between global and local dimensions.

-

The expansion of access and democratization of higher education.

-

Relevant aspects in the organization and management of higher education.

These themes necessitated the organisation of chapters into three distinctive passages:

-

Higher education themes within the context of globalization and internationalization.

-

Access to higher education and the characteristics of students.

-

Diverse perspectives on higher education policies and practices.

Higher Education Themes within the Context of Globalization and Internationalization

The first theme covers those reforms in higher education that depart from guidelines of a supranational sphere to national and regional areas. Between the global and the local, this process approaches the strains and tensions that emerge in different contexts of higher education. These may be regional, national, or institutional in nature.

The global dimension emanates policies formulated by transnational corporations—OECD, UNESCO, the World Bank, and the WTO—directed by the main trends within higher education in the last 30 years: expansion, globalization, and internationalization. These trends involve market rules associated with new versions of neo-liberalism. They also encompass the rationality of the management and autonomy of HEIs. Alongside these they also include the institutionalization and diversification of courses. And finally they consider the reformulation of educational curricula, evaluation systems, access, equity and quality, as well as the financing of higher education.

Among these challenges is the internationalization of higher education. As a guideline and an international trend for higher education systems, the internationalization process receives different interpretations depending on the context in which it is implemented, and the resistance it encounters. Considered locally, this process can be analyzed from a national point of view (Chapters 2 and 3) or from the point of view of higher education institutions (Chapters 4 and 5).

The approach of internationalization in emerging countries and young democracies shows how international policies can be absorbed within political and economic forces, as well as they can influence the trajectory of higher education in each national context (Chapter 2). Likewise, determinations from international institutions, such as the World Bank and the OECD, point to the “diversification within the system.” This may lead to differences relating to “access and affirmative policies.” It may also affect “institutional autonomy,” which may be implemented depending upon the political stage of each country. The political system of each country faces many different conflicts of interest. These are aligned to the political, economic, cultural, and even religious orders prevalent among countries included in this book.

At the local level, political, economic, social, and cultural aspects influence the stage of national systems of higher education. Each country, in this sense, assesses the implementation of a global agenda which involves different tensions. On the one hand, by national priorities and conditions in the definition of strategies for the expansion of access to higher education and the adjustment of institutions, and, on the other hand, by movements of criticism and resistance to standards imposed by commercialized and highly competitive models (Chapter 3).

The tensions occur simultaneously in the macro and micro levels: the relationship between public and private, institutional configuration, management of HEIs, the curricula, the meanings applied to teaching and learning, and the transmission of knowledge. The forms of teaching and learning and the use of information and communication technology underpins many of the chapters in this book.

In spite of perceived resistance, the conditions for the imposition of a new order in the universities remains durable and demonstrates the emergence of new models and challenges for higher education in the future.

As complex organizations, HEIs also react in different ways and at different times to internationalization strategies. Therefore, to understand the behavior of an institution, and to explain the way it organizes and defines its strategies for internationalization, becomes a significant step.

National contexts, within which a country’s HEIs fall, may well be at different stages when it comes to policies of internationalization. To understand these stages in young HEIs within different countries, the model developed by Minna Söderqvist (2007) has proved to be greatly applicable (Chapter 4).

According to Söderqvist’s model, HEIs can be classified into five levels, considering the breadth and stage of integration of internationalization action among senior management, departments, and courses. The model has proved to be useful for the identification of barriers and institutional challenges, in particular concerning the flow of communication and institutional alignment for internationalization.

The management and governance of policies of globalization and internationalization, driven by international bodies and associated with the vision of New Public Management (NPM) , are causing changes in HEIs (Chapter 5). Despite the significant differences between the organization and funding of higher education systems, common strategies were identified between institutions regarding rationality and the adoption of the principles of NPM in its governance.

Access to Higher Education and the Characteristics of Students

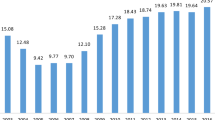

The steady growth of enrollment in higher education courses throughout the world and the change in the profile of the students scored, according to Trow (2000), constitute important aspects in the evolution of the particular character for the massification and the universalization of access to higher education. However, this process has occurred without any guarantee that a student will benefit from democratic entry into an HEI. This is especially evident in terms of accessing undergraduate courses. The evidence available seems to beg the question “for whom is higher education meant?”

Despite the significant increase in enrollment numbers in HEIs globally, in recent years, gaps have been shown to exist in certain sectors, predominantly those with economic, social, political, cultural, and geographical factors. Addressing such matters is crucial if equal access to higher education is to be the end goal (Chapters 6, 7, and 8).

The growing trend in enrollment is distinct in developing countries in Latin America (Chapter 6) and Africa (Chapter 7) from European, developed countries. The inequalities in entry, permanence, and the conclusion of higher education courses are mostly determined by socioeconomic stratification. Observations suggest that the difficulties faced by disadvantaged groups, such as blacks, indigenous peoples, and people with disabilities (Chapter 6), remain.

In African countries, such as Cape Verde and Angola, and Latin American countries, such as Brazil and Mexico, there is a large young population who are still without access to higher education. To change this reality, public policies need to consider both university selection systems and funding models. It is essential that the formulation of such policies considers current knowledge of the factors that lead to educational inequities and provides a thorough diagnosis. Without taking these two factors into consideration, they risk contradicting the principle of education as a fundamental human right.

In this sense, studying the perceptions of governing boards regarding exclusion factors, highlights just how easy it is for inequities in higher education to appear. Such factors as personal characteristics, family situation, institutional features, public policies, and phases of development of university students are discussed in Chapter 8. Such analyses have led to the classification of predictors of vulnerable groups in two major dimensions: intrinsic, related to individuals, and extrinsic, related to institutions.

In order to change the effects of these inequalities within undergraduate students, the authors point out some challenges to achieving a more inclusive higher education, involving information systems, leadership and management, as well as the priority of associating institutional action to community initiatives. These strategies have significant potential to progress complex, heterogeneous inequality scenarios.

Diverse Perspectives on Higher Education Policies and Practices

As well as the tendency to consider higher education as a global phenomenon, internalization is also considered a worldwide phenomenon. In spite of the trends in internationalization of education, some aspects that relate to national and regional scenarios may interfere with its expansion. Government policies and the cost of study generally help to expand domestic capacity. The use of English as an international language of teaching, e-learning, the growth of the private sector, and quality assurance and control all influence the continued expansion of education as a saleable commodity (Altbach and Knight 2007). Thus, policies and practices that focus on curriculum (Chapter 9), assessment (Chapter 10), systems of financial aid (Chapter 11), and relations with labor market outcomes (Chapter 12) deserve special attention because they evidence how national systems work in terms of such challenges.

From the perspective of internationalization, the growth of transnational higher education (TNHE) is increasing the provision of courses and programs in various areas and focusing on the development of intercultural skills (Chapter 9). TNHE is performed in different formats, more often than not employing virtual education, partnership programs, joint or double degree programs, studying abroad, and international branch campuses.

The case study in Chapter 9 deals with the discipline of management in international programs, offered in three different countries and continents, with the goal of promoting the development of skills in cross-cultural management, requiring that the development of methodologies of teaching and learning be differentiated.

The results affirm that curricula and international programs need to take into account the context of global and local aspects, as well as the incorporation of cross-cultural perspectives on pedagogical discussion and the training of tutors.

Assessment policies assumed greater relevance from the mid-nineteenth century to the twenty-first century and represent one of the ways of ensuring quality and greater control over the expansion of education systems throughout the world. As national policy may be powerfully directed by guidelines drawn at the supranational level, evaluation is, at the end of the day, the responsibility of the state. This is the case in the majority of national systems of higher education. Thus, the state plays a central role, but one that is linked to the political, economic, and educational systems of individual countries and whether HEIs are profit or non-profit organizations.

The study of three systems of evaluation of higher education, using data on mechanisms of assessment, enrollment, and type of HEI—profit or non-profit—provides evidence of a direct relationship between characters of the major responsibility for the offer and the characteristics of the evaluation. The regulatory nature of quality assurance in the higher education sector is considered in Chapter 10. Despite this, results of higher education assessments provide stakeholders with information that is helpful in terms of decision making. How stakeholders use such results, and how the state communicates such results to society represent significant future challenges.

Another fundamental issue, evident in the process of the expansion of higher education, in the scenario of globalization and internalization and local contexts, is funding. It is a fact that such an expansion is not occuring equally worldwide. One challenge is to resolve the issue of financing higher education to expand the number of enrollments, taking into account inequalities and scenarios of low economic growth and reduced state investment in education. Thus, planning for the growth of higher education needs to consider student financing and, consequently, the mechanism of student financial aid .

A study of the systems of financial aid in two developed countries and one developing country highlights the similarities and differences between countries as well as the ways that they approach funding growth (Chapter 11). The main similarity is that decisions about funding and regulation occur at the national level of government. The differences are connected to the criteria and mechanisms adopted regarding student financing systems. After analysing the three loan schemes, the authors present suggestions for reforms in the student financing system in Brazil, proposing a format that means to be integrated, fair and efficient.

Another important point raised in Chapter 11 is the institutionalization of tuition fees in public HEIs in Brazil, with higher education being free in state institutions. The authors defend such a position arguing that tuition fees are necessary also in the Brazilian state institutions.

However, this is a controversial issue that awakens many debates.

To conclude the studies in this third and final section, policies and practices of higher education, are related to an essential function of a university in society, that is, the formation of qualified professionals for the labor market. Thus, it is expected that making higher education available to more people will have a positive impact on the labor market.

However, historically, this relationship is not linear and/or direct. In many situations, this expectation is frustrated, for many different reasons. This effect is emphasized in the comparative analysis of the labor force in Muslim and non-Muslim countries, taking into account three dimensions: country, gender, and educational level (Chapter 12). In addition to these dimensions, the expansion of access to investment in higher education is also considered—the focus being on the participation of women with higher education in the labor market.

The results of this analysis highlight that differences between the participation of men and women in the labor force occur in different ways and as a result of a combination of factors: economic, social, cultural, educational, and religious. The expansion of women’s participation in the labor force is not determined only by higher qualifications. Thus, studies are required to deepen the analysis of relations between higher education and the labor market in different countries—a critical dimension that needs to be considered in order to increase our understanding of higher education as a public good.

Conclusions

This book was charged with the task of studying policies and practices of management within the diverse body that consists of Higher Education globally. The adoption of a range of international and comparative methodology practices enabled many different countries to be compared throughout this volume. By using a variety of comparison techniques across the various systems included, institutions, programs, innovations, results and cultures were able to be successfully contrasted and compared. As one part of a series of such Intercultural Studies in Education, each chapter was required to include at least one developing country and must include countries from at least two distinct continents. This stringent pre-requisite of the book allowed for a very specific and unique comparison to be made.

In the template of internationalisation and globalisation, the comparative perspective of analysis met in the book expanded visibility to dilemmas and challenges that pervade the multivarious national systems of higher education, each in different stages of development. The results offered within this edited volume has allowed for the emergence in a general manner from what was from the beginning a fairly consolidated perspective.

The dynamics involved within all societies where knowledge is taken to be the propelling factor of the economy, while also being linked to the political, social and cultural rights of those respective countries is clearly evidenced. The need to enable greater expansion and accessibility to further improve the quality and sustainability of higher education in all contexts studied remains as the guiding mission of this work.

While the attempt to portray the heterogeneity and diversity in higher education is a complex task, it is possible to do so. Further, it may be argued that it is considerably more complex to compare countries at different stages of economic and social development. In all analyses presented within this volume, the perspective is to look at the recent changes globally and then to present these changes to enable the identification of those relevant aspects within the context of the role of higher education in the future.

In the growth observed in the increase of enrollment and the diversification of courses and institutions worldwide, tensions inevitably exist. These may be seen between the public/private sector, the commodification of education, financing systems and the role of the State in the development of these multifarious sectors. This clearly demonstrates the importance of debates about higher education as a public good, in individual and social benefits (Marginson 2011b), or as a product of the market.

This discussion invokes the priority of policies for equity and equality, which are conducive to entry into Higher Education institutions. The potential, therefore, to ensure the permanence and quality of training with groups of non-traditional students in higher education is assured. The inevitability of exclusion to some sectors in a wide range of vulnerable situations may therefore be eliminated. Such factors that must clearly be allowed optimum opportunity may include but are not necessarily restricted to issues associated with the social class, race/colour, ethnicity, gender and religious beliefs of aspirants to the sector.

Finally, one of the embracing requisites required by all contributors to this book was that it stood out just how important the open nature or character of the book was. This enabled different positions and analyses in respect of topics relating to higher education to unfold and emerge. Finally, the necessity for such an approach to cross-cultural studies became clear. Such a democratic character was deemed as an essential aspect in the scientific production of education encapsulated in this volume.

Definitions

-

BRICS refers to the strong economies of the newly emerging nations, Brazil, Russia, India, and China.

-

GAFA is a term coined in France referring to the most powerful companies in the world, namely, Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon.

-

IPBS stands for Institutionalized Public Basic Schooling. As Dasen and Akkari point out, this model has become so widely accepted throughout the world that it is no longer seen as Western. “Scientific knowledge about education is typically seen as Western and, if anything, non-Western contexts are only the objects of study upon which Western paradigms of inquiry are imposed” (Dasen and Akkari 2008, p. 8).

-

OECD is the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. It was founded originally in 1961 and initially had only economically advanced countries as members. It now has 36 members and was one of the first organizations to use education indicators in support of what is now commonly referred to as human capital theory. The theory being that the stronger the education sector the more developed an economy would be. Theodore Schultz is widely acknowledged as the principle protagonist who linked human education standards with economic success—many adopted the mantra. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in economic sciences in 1979. There is certainly a connection between the robustness of an education sector and the strength of the national economy.

References

Altbach, P. G., & De Wit, H. (2017). Internationalization and Global Tension: Lessons from History. In G. Mihut, P. G. Altbach, & H. De Wit (Eds.), Understanding Higher Education Internationalization: Insights from Key Global Publications (pp. 21–24). Rotterdam: Sense Publisher.

Altbach, P. G., & Knight, J. (2007). The Internationalization of Higher Education: Motivations and Realities. Journal of Studies in International Education, 11(3), 290–305.

Bagnall, N. (2011). Know Thyself: Culture and Identity in Comparative Research. In L. Markauskaite, P. Freebody, & J. Irwin (Eds.), Methodological Choice and Design: Scholarship, Policy and Practice in Social and Educational Research, (pp. 203–208). New York: Springer.

Beck, K. (2012). Globalization/s: Reproduction and Resistance in the Internationalization of Higher Education. Canadian Journal of Education, 35(3), 133–148.

Bleiklie, I. (2005). Organizing Higher Education in a Knowledge Society. Higher Education, 49(1–2), 31–59.

Bray, M. (2014). Comparative Education Research: Approaches and Methods. CERC Studies in Comparative Education, 19. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05594-7-_1.

Castells, M. (2000). The Rise of the Network Society (Vol. 1). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

Chan, S.-J. (2012). Shifting Patterns of Student Mobility in Asia. Higher Education Policy, 25, 207–224.

Chapman, D. W., & Austin, A. E. (2002). Education in the Developing World. In Higher Education in the Developing World: Changing Contexts and Institutional Responses (pp. 3–21). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Cloete, N., Bailey, T., Bunting, I., & Maassen, P. (2011). Universities and Economic Development in Africa. Oxford: African Books Collective (CHET).

Dasen, P. R., & Akkari, A. (2008). Educational Theories and Practices from the Majority World. New Delhi, India: Sage.

De Wit, H. (2017). Internationalization of Higher Education: Nine Misconceptions. In G. Mihut, P. G. Altbach, & H. De Wit (Eds.), Understanding Higher Education Internationalization: Insights from Key Global Publications (pp. 9–12). Rotterdam: Sense Publisher.

De Wit, H., Gacel-Ávila, J., Jones, E., & Jooste, N. (2017). The Globalization of Internationalization: Emerging Voices and Perspectives. London: Routledge.

Drucker, P. (1959). Landmarks of Tomorrow: A Report on the New Post-modern World. New York: HarperCollins.

Foray, D. (2000). L’économie de la connaissance. Paris: La Découverte.

Giddens, A. (1990). The Consequences of Modernity. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Goddard, J., Hazelkorn, E., Kempton, L., & Vallance, P. (Eds.). (2016). The Civic University: The Policy and Leadership Challenges. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Gyamera, G. O. (2015). The Internationalisation Agenda: A Critical Examination of Internationalisation Strategies in Public Universities in Ghana. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 25(2), 112–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/09620214.2015.1034290.

Hazelkorn, E. (2015). Rankings and the Reshaping of Higher Education: The Battle for World-Class Excellence. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jooste, N., & Heleta, S. (2017). Changing the Mindset in Internationalisation Research. In G. Mihut, P. G. Altbach, & H. De Wit (Eds.), Understanding Higher Education Internationalization: Insights from Key Global Publications. Rotterdam: Sense Publisher.

Kaiser, F., Maassen, P., Meek, L., Van Vught, F., De Weert, E., & Goedegebuure, L. (1994). Higher Education Policy: An International Comparative Perspective (379pp.). Pergamon. EBook ISBN: 9781483297163.

Klemenčič, M. (2018). Higher Education in Europe in 2017 and Open Questions for 2018. European Journal of Higher Education, 8(1), 1–4.

Knight, J. (2008, October–November). The Internationalization of Higher Education: Are We on the Right Track? Academic Matters, 52, 5–9.

Kwieck, M. (2001). Globalisation and Higher Education. Higher Education in Europe, 26(1), 27–38.

Marginson, S. (2011a). Introduction to Part 1. In R. King, S. Marginson, & R. Naidoo (Eds.), Handbook on Globalization and Higher Education (pp. 3–9). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Marginson, S. (2011b). Higher Education and Public Good. Higher Education Quarterly, 65(4), 411–433.

Marginson, S. (2016). Higher Education and the Common Good. Melbourne: Melbourne University Publishing.

Markauskaite, L., Freebody, P., & Irwin, J. (2011). Methodological Choice and Design: Scholarship, Policy and Practice in Social and Educational Research. London and New York: Springer.

Mihut, G., Altbach, P. G., & De Wit, H. (Eds.). (2017). Understanding Higher Education Internationalization: Insights from Key Global Publications. Rotterdam: Sense Publisher.

Mora, J.-G., Serra, M. A., & Vieira, M.-J. (2018). Social Engagement in Latin American Universities. Higher Education Policy, 31(4), 513–534.

Nitz, A. (2017). Why Study in Latin America? International Student Mobility to Colombia and Brazil. Bielefeld: Universität Bielefeld.

Noorda, S. (2014, March). Internationalisation in Higher Education: Five Uneasy Questions (Humboldt Ferngespräche—Discussion Paper No. 2).

Salmi, J. (2002). Higher Education at a Turning Point. In D. W. Chapman & A. E. Austin (Eds.), Higher Education in the Developing World: Changing Contexts and Institutional Responses (pp. 23–43). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Salmi, J. (2017). The Tertiary Education Imperative Knowledge, Skills and Values for Development. Rotterdam, Boston and Taipei: Sense Publisher.

Schwarzman, S., Pinheiro, R., & Pillay, P. (Eds.). (2015). Higher Education in the BRICS Countries. Dordrecht: Springer.

Sehoole, C., & Knight, J. (Eds.). (2013). Internationalisation of African Higher Education: Towards Achieving the MDGs. Rotterdam, Boston and Taipei: Sense Publishers.

Tamrat, W. (2018, April 20). The Importance of Understanding Inward Student Mobility (Issue 502). University World News.

Teichler, U. (2017). Internationalisation Trends in Higher Education and the Changing Role of International Student Mobility. Journal of International Mobility, 1(5), 177–216.

Trow, M. (1972). The Expansion and Transformation of Higher Education. International Review of Education, 18(1), 61–84.

Trow, M. (2000). From Mass Higher Education to Universal Access: The American Advantage. Minerva, 37(4) (Spring), 1–26.

Wihlborg, M., & Robson, S. (2018). Internationalisation of Higher Education: Drivers, Rationales, Priorities, Values and Impacts. European Journal of Higher Education, 8(1), 8–18.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

de Albuquerque Moreira, A.M., Paul, JJ., Bagnall, N. (2019). The Contribution of Comparative Studies and Cross-Cultural Approach to Understanding Higher Education in the Contemporary World. In: de Albuquerque Moreira, A., Paul, JJ., Bagnall, N. (eds) Intercultural Studies in Higher Education. Intercultural Studies in Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15758-6_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15758-6_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-15757-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-15758-6

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)