Abstract

Traumatic events can cause deep wounds in the physical, emotional and psychological experience of the situation. The experience of traumatic events has been identified as a risk factor for the development of a large number of psychiatric disorders, between them, PTSD, eating disorders, depression and psychosis. In fact, in individuals suffering from severe psychiatric disorders, childhood trauma is reported at a much higher rate. In this chapter, we will try to review the different dimensions of the suffering and emergence of trauma in holistic, gender-sensitive and integrated ways. The body is the epicentre of trauma in its individual experience, identity impact and excruciating remembrance of the event. Yet sociopolitical contexts and their ruptures also inhabit the human body: violence, poverty, abuse and oppression. Thus, understanding trauma requires giving specific attention to the sociocultural fabric in which the wound is inscribed and suffered. In the first part of this chapter, we will approach to the historic perspective of the origins of trauma, trying to define the elements around this complex concept. In the second part, we will consider from a holistic integrative biopsychosocial perspective the biological and psychopathological aspects that may emerge after a traumatic event.

You cannot imagine you would ever do /You are going to do bad things to the children/you are going to suffer in ways you have not heard of /you are going to want to die…./I say /Do what you are going to do, and I will tell about it.

Sharon Olds. The gold Cell.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction: A Brief History About Hysteria and Trauma

The concept of trauma has been ubiquitously defined throughout human history. Body images have been deconstructed and reconstructed in the course of the centuries. To understand the history of trauma, we must go further back in time, when neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot carried out the study on hysterical women in Salpetriere Hospital, France. This condition was largely considered a women’s disease which presented a wide variety of symptoms, including amnesia, paralysis states and sensory loss. Charcot was the first of his generation to understand that these symptoms stemmed from a psychological nature rather than a physiological one and, more importantly, that the effect of traumatic events could induce those states. But despite his discoveries, he had little or none interest in these hysterical women’s inner lives. Years later, some of Charcot’s successors like Pierre Janet or Sigmund Freud tried to overcome his work by demonstrating the cause of these hysterical symptoms. It was by the mid-1880s when Janet and Freud, yet almost at the same time, came to the conclusion that hysteria was a condition caused by psychological trauma. Those traumatic experiences (such as rape) could cause unbearable emotional reactions which resulted in an altered state of patient consciousness that, in turn, induced these hysterical symptoms. By 1896, Freud made a discovery from his talks with his patients that would become a milestone in understanding the underlying causes at the origin of his patients’ symptoms [1]:

I therefore put forward the thesis that at the bottom of every case of hysteria is one or more occurrences of premature sexual experience, occurrences which belong to the earliest years of childhood

Since the Belle Époque of hysteria and hypnotism, the study of hysteria changes dramatically by the discovery that those events not only occur in the lower strata of the society but also in bourgeoisie and aristocracy. The atrocities exposed by those women’s reports were unbearable and, as a consequence, relegated the study of hysteria and trauma to a state of “denial and oblivion”.

As said by Judith Herman in her book, Trauma and Recovery, there is continuing controversy on trauma and memory [2]:

The study of psychological trauma has a curious history –one of episodic amnesia. The study of psychological trauma does not languish for lack of interest. Rather, the subject provokes such intense controversy that it periodically becomes anathema

Following Herman Freyd points out “among the traumatic events that result in an intense controversy that periodically becomes anathema, sexual abuse of children seems to be the most revolutionary” [3]. Very often, societies protect themselves from pain and suffering through oblivion, but as it happens, in some cases, the best way to forget is through memory and the conscious and emotional recognition of the event. While preserving the memory in the past, we displace the painful engravement of the event. The stories can be used to empower and to humanize people, but they can also humiliate and broke the dignity of those people affected [4].

Depending on the sociopolitical and cultural context of the moment, the study of trauma is oblivious or denied. In our social and political moment, the ongoing debate on the concept of psychic trauma is still in force, and the notion has been changing with the international classifications in the DSM and the ICD throughout its editions and revisions. To date, there is not a universally accepted definition of trauma.

Related to trauma, the body has an important role. The body is often referred to as a thing intersected by society, biology, subjectivity, history, etc. Etymologically, the notion of intersection takes us to cut, to node, to section and to sword. The act of intersection as a concept about the body pierces its image of inscrutability. The body penetrated by trauma will no longer be a mere bearer of signs and symptoms; instead, it will be able to capture sense and create meanings to be integrated in its identity. In phenomenology, the corporeality is the lived and living body: “The world is not what I think but what I live through” [5].

Nevertheless, in Western societies, the body has been and is undervalued against the pureness and overvalued reason, most of them in a moral sense, but still not giving way to Je sens, je pense en dedans de moi. Excessive expressiveness and body movements are left in the powerful hands of oblivion, and symptoms become central. The body is extremely hierarchized in our culture as an image, a flat image that ceased to be volume to become a glowing silhouette highlighted in the screen, but with no subjective lived events. In trauma, silence is broken in giving way to the lived body. In the diverse contributions to the concept of trauma, aspects related to corporality as the most lived experience of the traumatic event are not always included.

Following the biopsychosocial model, we know that the diverse environmental and sociocultural aspects are risk factors in psychopathology and that they manifest complex interactions with neurobiological elements, which frequently are directly connected to gender. In trauma, when we consider the experience of traumatic events, this panorama is maximized and sociocultural factors such as the absence of social support and family’s exposure to violence are in this context, determining. Thus, and as described in the literature, women are more likely to be exposed to some harmful environmental aspects causing the development of the disorder (sexual abuse), while men are more likely to be exposed to other factors (physical abuse).

In this chapter, we will try to review the different dimensions of the suffering and emergence of trauma in holistic, sociobiological, gender-sensitive and integrated ways. The body is the epicentre of trauma in its individual experience, identity impact and excruciating remembrance of the event. Yet sociopolitical contexts and their ruptures also inhabit the human body: violence, poverty, abuse and oppression. Thus, understanding trauma requires giving specific attention to the sociocultural fabric in which the wound is inscribed and suffered. It means reviewing integrating models in which the diverse dimensions of suffering are considered, gathering the much-heralded but less-performed psychosocial approach to health [6].

In the first part of this chapter, we will approach the historical elements surrounding the concept of trauma considering corporality and its gendered embodied reality. In the second part, we will approach the concept of trauma from a holistic-integrative perspective around the extensive disruption that occurs in identity and in corporeality. The psychopathological conditions that may emerge after a traumatic event are many and varied; even though we will not attempt to cover them all, we will try to give an approach to two of the expressions more affected by gender: somatization and self-harm. In parallel, these two expressions are closely related to early sexual abuse, a particular form of psychic trauma. Finally, we conclude with some sociobiological considerations related to the exposure to traumatic events.

2 Concept of Trauma

Trauma can be defined as an unbearable experience for a person’s cognitive and emotional patterns. In fact, trauma poses a challenge for the identity of the individual, as it questions the relational world of the subject. [7]. To approach and understand the concept of trauma, we must consider as described by Carlson and Balenger [8] the three identifying features of traumatic events. Those inner characteristics are the negative valence of the experience, the lack of uncontrollability of the situation and the suddenness.

-

The negative valence refers to the experience of the perception of the event as negative. Although the valence of an event is something subjective, death of a loved one or physically painful events are almost considered in all cultures as a negative experience.

-

The lack of controllability, the perception which determines the magnitude of the experience. It is important to note that the uncontrollability of an event must reach a certain threshold to cause traumatization and is variable across individuals.

-

The suddenness is considered as the core characteristic of a traumatic event. The suddenness of an event is an essential part of what makes and experience traumatic. Events that involve imminent threat of harm are more likely to cause overwhelming fear than experiences involving danger that is not imminent.

Because the considerable effects of traumatic experiences have negative effects on physical and emotional health, the prevalence of traumatization following such a traumatic experience is not seen in the vast majority of population. Recent studies have brought to light that general population, at least, has been exposed to one traumatic experience in their lifetime, with a range variety between studies from 28 to 90%. Frequently, as reported by those studies, the most common events being considered as a traumatic experience are the unexpected death of a loved one, motor vehicle accidents and being mugged [9].

Despite that, there are other sociocultural factors that are poorly understood or not investigated, such as gender, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity or age. In 2016, Benjet and his colleagues [9] performed an epidemiological analysis of the presence of traumatic experiences worldwide. They looked up for more than 29 different types of traumatic experiences in a sample of 68.894 adult respondents across 24 countries. The results were impressive: over 70% reported at least a traumatic event during their lifetime, and 30.5% at least reported four or more traumatic experiences. Finally, analysing the socio-demographic predictors of traumatic exposure, they discovered that females were more likely than males to be exposed to intimate partner/sexual violence (OR = 2.3) [9].

To understand the concept of trauma, there are different itineraries to approach traumatic pathology, but not all of them consider one important part of experiencing a traumatic event: the corporal dimension.

In fact, not all the traumatic events cause a similar impact, nor they are associated with a similar symbolic significance. Thus, traumas responding to extreme experiences are hardly classified in the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) diagnosis, in that they will have devastating consequences on the psyche, in the corporal experience and, as a result, in the being-in-the-world.

PTSD has attracted controversy since its introduction in 1980 as a psychiatric disorder in the third edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM III). Since then, there have been subsequent changes, modifications and criticisms from the original classification of PTSD firstly allocated in the anxiety disorders section (avoiding or relegating the importance of some experiences such as guilty, shame or anger followed by a traumatic experience). The most polemical argument is concerning the definition of trauma or even whether it is a valid diagnosis itself.

As described by Judith Herman in 1992 [10], she defines these disorders as DESNOS (disorders of extreme stress not otherwise specified) or complex PTSD. This syndrome is defined in three dimensions: symptomatology, character traits and vulnerability to repeat harm [2]. In this way, PTSD in its definition of consequence of a traumatic event is distinguished from the chronic trauma associated with extreme horror, such as prolonged domestic violence.

The introduction of this frame expanded the diagnostic criteria in order to demonstrate the profound changes and transformation of the personality experienced by persons exposed to this extreme traumatic experience.

Attending to those new changes introduced in the definition of PTSD in the DSM V, some scientists have pointed out that the criterion A of PTSD, “exposure to a traumatic event”, is too inclusive [11]. As described by Pai and colleagues, not all stressful events involve trauma itself. Stressful events not involving an immediate threat to life or physical injuries or psychosocial stressor, such as complicated divorce or a repentant job loss, are not considered trauma under this definition [12].

In contrast, although not being conceptualized in the DSM, there is a category in the ICD-10 titled “enduring personality change after catastrophic experience”.

Thus, among the symptoms included, there is a broad range of bodily symptomatology (not present in PSTD) such as diverse forms of somatization (chronic pain and digestive, conversion, sexual and cardiopulmonary symptoms) as well as an alteration of the affects and impulses, which implies, inter alia, self-destructive behaviours. In many cases, the patients experience continued headache, heartburn and urinary infections [13].

PTSD is defined as the exposure to a traumatic event leading to re-experiencing symptoms (corresponding to the reliving of the traumatic event: images, thoughts, dreams, etc.), avoidance behaviours, increased arousal in the forms of irritability, hypervigilance, concentration problems, etc. However, the DSM-IV lacks a broader definition on the types of trauma, so that any event resulting in “death or threats to life and limb” was included. The DSM 5 [14] clarifies that a traumatic event may be threats or death, serious injury or sexual violence. This is the first time sexual violence appears specifically acknowledged as a traumatic event.

A lot has been written about the definition of trauma in its two essential components: as an extreme striking event and as the human response to that event. The DSM-IV required a response accompanied by intense fear, helplessness or horror, not accepting the exposure to a traumatic event as a cause of the disorder.

Nevertheless, regarding the diagnostic criteria in the DSM-5, the criterion A2 involving “intense fear, helplessness or horror” has proved to have little utility in the diagnosis, and thus, it has been eliminated. The authors point out that the response to trauma, apart from terror or fear, may include dysphoric mood, anhedonia, negative thinking, dissociative symptoms and so on. The variability of human behaviours and expressions for distress were the reasons to drop A2 criterion in trauma definition.

There remains strong controversy on this subject, given that it has been demonstrated that in traumatic events involving physical integrity such as armed or unarmed rape, the self-perception of menace is the best predictor of PTSD symptoms [15]. Although the incidence for traumatic events is higher in men, studies have demonstrated that women have a double risk for developing PTSD [16] and present a lower rate of symptom remission.

From a pure phenomenologist perspective, some reflection could be considered in PTSD diagnosis of the multiplicity of the human response to trauma and its heart-rending experience and the bodily experience in the traumatic event [17]. In the following excerpt by the Auschwitz survivor Jean Améry (1912–1978), we approach the most humane regard of a violence and torture victim. The body, as an intimate territory, is penetrated by the monstrous, the vile and the evil. The lived body is the fuel for the visibility of a soul tormented to suicide.

The crimes committed in Auschwitz I and Birkenau during the Nazi regime in Germany overpass the limits of human cruelty. As described by Améry, all the atrocities committed marked a before and after not only in history but also in the lives of millions of people.

The real horror began, however, when the SS took over the administration of the camps. The old spontaneous bestiality gave way to an absolutely cold and systematic destruction of human bodies, calculated to destroy human dignity; heath was avoided or postponed indefinitely. (…) I must confess that I don’t know exactly what that is: human dignity (…). Yet I am certain that with the very first blow that descends on him he loses something we will perhaps temporarily call “trust in the word”. (…) But more important as an element of trust in the world, and in our context what is solely relevant, is the certainty that by reason of written or unwritten social contracts the other person will spare me –more precisely stated, that he will respect my physical, and with it my metaphysical, being. (…) It is like a rape, a sexual act without the consent of one of the two partners. Certainly, if there is even a minimal prospect of successful resistance, a mechanism is set in motion (…) the border violation of myself by the other, which can be neither neutralized by the expectation of help nor rectified through resistance.

This extract underlines some nuclear criteria in the traumatic event as an experience penetrating the body in full: completed rape, frequently linked to extreme emotions, experience of chaos, confusion during the event, memory breakup, absurdity, horror, ambivalence, disconcert, humiliation, despair, loss of control and helplessness. This delineates the bodily experience through alienation and limit invasion.

3 Identity Intersections

Addressing corporality in the common experience of trauma presupposes a consideration of the gendered dimension of our experience. The sudden shock in a traumatic event and the resultant narrative disruption do not cause a shifting, nor they override gender; they rather structure common experience. These identity coordinates are analytical tools that enable us to better understand subjectivity and suffering, particularly in women. It is not that women need neither footnotes nor chapters different from the human but rather “both from an epistemological perspective as well as in biomedical practice, the ‘normality’ pattern has been and continues to be the hegemonic masculinity” [18].

Gender inequality is not determined by biological facts. This is the reason why gender perspective does not conclude nor is limited to a gender breakdown in the statistics for psychic distress prevalence and incidence. It is not about searching, describing and confirming differences between sexes but rather about explaining such differences. Gender is relational and dynamic, a structure of relations continually interacting. Thus, gender perspective implies considerations that go beyond the “mystic of numbers” and the essentialist constructions on sexual characteristics of each sex, in order to contextualize data in a well-defined social framework [19].

In fact, feminist authors denounce that the complexity of traumatic experiences of women has not been considered by the prominent model for trauma in a society divided by gender [20, 21]. Other contributions from this same perspective include the incorporation of some groups neglected by the PTSD first diagnosis, such as women and children survivors of sexual abuse [22], the reformulation of key concepts such as “coping strategies” instead of symptoms [23] and the warning that gender violence is a disproportionate everyday occurrence not only in war but also in peace contexts [19, 24].

Suffering intersects gender, age, ethnicity, disability, beliefs, economic status and other global processes affecting local environments. In other words, there is not a single way to suffer, and the expression and perception of pain are different even within members of the same community [25]. Nevertheless, the due consideration to particular contexts with their own cultural and identity settings, their own sources of domination and inequality, will enable us to broaden our perspective and in doing so, to better understand the traumatic event, the consequent grief and process of recovery where they unfold. As Janzen reminds us: “[…] although war trauma certainly has physical consequences and imprints, it is culturally mediated and that is where its character, causes, consequences and avenues of resolutions may be best understood” [26].

4 Identity and Corporality: Providing a Framework for Situations of Violence and Trauma

Identity is the sense of self and oneself in the world. Namely, it is the self-image in each context, as there is not only one self defining the person yet multiple selves in coexistence [17]. Thus, we understand that human bodies are recognized in diverse identities/selves in the world they live and coexist [27].

However, human beings develop the sense of being one—the sense of self—through the construction of a unique narrative identity. An identity while experienced as unique encapsulates the idea of permanence and change: projection into the future and recognition in the past [7].

Throughout history, we are reminded that the sense of self is first and foremost a bodily/corporal sense, experienced not through language but rather through body motion and sensation [28,29,30]. This experience of the somatosensory initial corporality will eventually form a narrative self, a sense of conscious versus the emptiness of inconsistency. A self-representation of the being in a dialectical relational process from birth, joint and reciprocal with the attachment relations, constructs and regulates identity.

The theory of attachment has many links with psychoanalytic theory, as it also delves into children’s response to trauma in its origin, the body being the first vehicle of identity.

Our body is our limit, our boundary. This is how Rodríguez relates to this subject “boundaries are the areas of separation or differentiation, but also of connection of the self and the others and the world”. Boundaries are configured around the relational experience. In these areas take place the interchange, the biological and emotional nutrition that are necessary to form the mind and the self-experience [7].

Along these lines, Bowlby notes “human beings need the attachment relationship as a regulator of their emotional system for the harmonious development of the self” [31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. The body appears to be the first provider of identity and the first vehicle for interpersonal communication between the child and the world. Thus, through primary feelings and physiological sensations, and later with auditory and visual stimuli, children will play an increasingly important role. Bowlby accentuates that the groundwork in the first year of life consists of building an attachment relationship, and Shore notes that this is the “the affective bond of emotional communication between the child and the primary caregiver”. Caregivers, in optimal conditions, help the child to identify and verbalize the affects, which are initially experienced mainly in somatic terms. Thus, the child learns to distinguish somatic experience from psychological experience [7].

This theory is based on the assumption that attachment with affective referents in childhood (mainly parents) will configure a damaged neurobiological structure, which would determine the adult abnormal response to trauma. From a moderate perspective, one would understand that the attachment style marks a tendency to response patterns that can be activated or not in stressful situations [17].

In this raising corporality, affection, historical condition, values and beliefs become interwoven, and social and subjective features, such as the primary identity and the generic condition, reengage.

This self is not only fluids, bones, finiteness and forcefulness, but rather it is what sets us apart from others. Dio Bleichmar maintains that the sense of femaleness is constructed in relation to the body, the attachment to others and love as the core of the identity [38]. In line with this, Husserl claims that the self only exists if embodied. Thus, following Merleau-Ponty, we see ourselves not as having but as being bodies.

Human bodies, apart from being expiring and deteriorable, following Cristóbal Pera, they are vulnerable, suffer trauma and become “injured bodies”. We are finite bodies exposed to a host of misery, trauma and pathology. Thus, the abused, raped or beaten body is deeply harmed in its bodily identity, leaving the self-helpless, defenceless like a 3-year-old boy. Freud addresses the body and comes to the conclusion that the ego is a differentiation from the id, due to the contact of the body with the outside world. In Freud’s words, the ego comes first and is mainly a corporal self [39].

Identities are relatively stable. There is a tendency to defend the coherence of the oneness, a tendency that preserves it from the normality and everydayness. There are only some experiences, such as the traumatic events, that may cause dramatic changes [17].

The traumatic event (or the recurring of the multiplicity of configurations of violence and trauma) as extreme questioning events will resolve key aspects of this identity. In this way, trauma not only acts as a questioning event of the self and the world, but also it can be inscribed as a defining event, a provider of meaning. In fact, the traumatic and painful event unleashes an experience of discontinuity which implies a denarrativization of the body. Thus, it provokes a disruption in the narrative conscience, through which everydayness is configured.

The process of integration of the traumatic experience involves the global readjustment of the person’s self-perception in the attempt to relocate the memories of the event. Paul Steinberg, Auschwitz survivor, describes the difficulties to reconcile identities: before Auschwitz, in the camp and afterwards as a parent. Sometimes the force and intensity of these elements of life are so powerful that it becomes nuclear in the identity of the person.

The trauma resultant identity not necessarily has a negative foundation. Betty Makoni is an African woman, a child abuse survivor, activist and founder of the Girl Child Network in Zimbabwe, Africa. Betty talks about how girls cope with trauma and the symbol of a tree that is born on the head of a woman whose roots are nurtured by their coping potential [40]. Once again, there are no intrinsically good or bad things but useful, adaptative and nonadaptative.

Along the lines of managing the own resources and the attribution of new meanings to the events as factors for the protection of the resultant identity, Kimberly Theidon reaffirms the important role of women raped in war as heroines in the defence and protection of their children, leaving the humiliation and stigma images behind. Anngwyn St. Just notes that the victim’s conscience, if we do not strengthen resilience resources and capacity, may have a negative effect on physical and mental health [41].

Pérez [17] notes that a trauma-centred identity only is troublesome if linked to images of vulnerability and powerlessness, dependent relationships, help seeking and grumbling, hindering the full development of the person. On this basis, Jean Améry asserted that psychiatry, labelling the survivors as “damaged” or “sick”, questions their moral legitimacy as privileged witnesses and makes them mere objects of cure and compassion. Thus, their voices are discredited, which is useful for the political class and to society at large.

Importantly, in working with people affected by psychological trauma, we must be especially sensitive and consider the risk of possible invalidation of the subjective experience and the subsequent revictimization [42]. In terms of gender violence but also applicable to other victims, Valiente [43] insists that blaming them for their vulnerability furthers revictimization even when victims need to understand the elements operating in their vulnerability, be it rooted in unveiled conflicts, fantasies, desires or unadaptive expectations. Chu [44] recommends working in a therapeutic alliance with the patient to prevent self-destructive actions and contribute to the understanding of the mechanism that makes them more vulnerable to revictimization.

Thus, it would be easy to think that trauma is embodied as an experience altering identity. However, it is in that immediacy of life where boundaries and pain awaken the body from its comfortable lethargy where we should broaden choice towards the power of being afresh and where lie infinite possibilities of experiencing living.

5 Violence, Experience and Care

Despite the policies made by the public health organizations, such as the ONU—Women, the National Institute of Health of the United States or the Sex/Gender Methods Group of the Cochrane group, concerning the inclusion of gender-based analysis in the methodological research aspects, not so many mainstream work and studies consider a gender perspective in their research.

Indeed, and related to the study of psychological differences presented by men and women, not so many studies consider or at least try to explain the psychological effects of distress in relation to the position of women and men have in the society. In particular, an approach to trauma must need to look into these factors, among others: sexual triggers for trauma, diversity in experience, dealing with suffering and expressing suffering, as well as gender-based analysis and methodological considerations. Following this approach, in this section, I try to cover the research and contributions that show the relevance of gender in violence, experience and trauma care.

5.1 Violence(s)

The Declaration of the Elimination of Violence Against Women celebrated in 1993 by the United Nations defines violence against women as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life” [45].

As described in the literature, certain groups are more likely to be exposed to interpersonal violence, and consequently, exposed to painful and traumatic experiences [46,47,48]. The fact that the main threats to individuals and communities are inscribed in some specific areas and territories proves that violence is not fortuitously distributed. Marginalized populations living in poverty, violence against women, racism, homophobia and other forms of oppression underline this. Some studies have shown that living in a disadvantage neighbourhood contributes to a higher risk for the development of psychological disorders [46]. This is not a new thing, social studies have focused in the risks presented by lower-income places, concluding that poverty and interpersonal violence are predictors directly related to mental health [47, 48].

As a matter of fact, the proposition maintained in the model of PTSD, which claims that the world is a safe place until exposed to a traumatic event, has been questioned. According to Burstow [23], this could be true for a white, middle-class, straight man, given that trauma is not a neutral but political experience.

Following the Galtung conflict triangle [49], there are three subtypes of violence. Firstly, direct violence is visible and clear, given that this type of violence is behavioural. Secondly, structural violence results from an unequal access to resources, material or otherwise, such as education, health, peace and, consequently, power and opportunities. Lastly, cultural violence refers to those aspects of violence that may be used to justify or legitimize direct or structural violence. Gender violence has its roots in culture—in fact, one of the senses of the word “violence” in Spanish, violencia, is “the act of raping a woman” (DRAE)—and in terms of its consequences, it emerges both direct and structurally. To illustrate this, there is supporting data: 1161 women violations are reported every year (Ministerio del Interior, Spain 2011). That means three a day, one every 8 h. Thus, structural violence, as Bourdieu [50] reminds us, is always perpetrated in countless of small and big acts of everyday violence that in most cases continue with impunity.

In the case of internal armed conflict, albeit they affect the whole population, there is evidence of gender dimension regarding grades of violence and suffering. While men are exposed to the risk of torture and mass killing, women are more likely to be victims of sexual violence and other types of violence, a violence that does not cease when conflicts officially end and normally occurs in the intimacy, in the private life. In 2001, Amnesty International denounced that violence against women is not incidental in war yet a weapon deliberately used for different purposes, like the spread of terror, the destabilization of society or as a means for rewarding soldiers and for extracting information. Such violence includes different assaults of sexual nature: rape and gang rape, sexual abuse, slavery, mutilation, forced impregnation and prostitution. In the gruesomeness of war, the way the logics of terror operate is made invisible. In fact, the broadcasting of numberless cases of rape and forced pregnancy in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia drew international attention to the magnitude of this form of cruelty against women in armed conflict.

In her work on the Haitian repression during and after the coup d’état in 1991, Erica Caple James [51] examines the influence of gender and its psychosocial after-effects. In this conflict, women were targeted on account of their active role in politics as well as their small-scale business role. They were also punished on behalf of their husbands, fathers and brothers, deemed as surrogate wives, taken as “sacrifical substitutes”. Their vulnerability to the attacks of different military groups flowed from the responsibilities towards their children and their business activities in local markets, which kept them visible and reachable. The different forms of torture were not only aimed at the delegitimization and bodily disempowerment through pain but also at destroying the production and reproduction of the victim, breaking social ties with the family and community through the violation of social norms. Broadly, the after effects of the traumatic event were embarrassment, humiliation and social isolation from the family and community. Raped women were frequently abandoned—labelled as “the rapist’s wives”—by their partners and families. Alienated from their social group, they moved to other areas to rebuild and restore their lives, and in most cases, their only resource to their survival was the reappropriation of their sexuality as a means to make a living. In the case of male victims of violence, the feelings of shame and humiliation were rooted in their incapacity to protect their families and in the degrading treatment and torture.

5.2 Experiences

Conception, construction, manifestation, symbolization and management of suffering are also intersected by gender. As stated by Távora [52], in some determined conflicts, the existing relations between perception and resolution and mental distress or mental wellbeing of women, are determined by the position the dominant system grants them—subordination. In other words, women’s distress is framed in a social psychopathology issue.

Inequality between men and women is intertwined by coercive elements, which are eminently corporal, and result in internalized relational models integrated in our subjectivity. According to the author, femininity makes us in such an identity that is centred in a being to be perceived, observed in a continuous state of bodily insecurity and symbolic alienation. In this identity, appearance has a fundamental value. Adolescent women, when bodily changes begin and secondary sexual characteristics appear, face their sexuality not through an encounter with their bodies but through the stripping gaze of the other [52]. This is what Basaglia [53] calls “being-for” and “being in the being-of-others”, which defines a socialization environment for women reinforcing the importance of attachment and the emotional. Following Rosaldo [54], to this we can add that: “It now appears to me that woman’s place in human social life is not in any direct sense a product of the things she does, but of the meaning her activities acquire through concrete social interaction”.

From a bodily experience, women tend to represent their bodies through instrumentality, dissociation and tension. The body is an instrument, the object to perform social, reproductive and productive functions. Alongside this, motherhood is the core where most women build their identities on. Motherhood and bodily reality are the constitutive elements of a dissociated reality where sexuality and sensuality coexist in tension [55]. In this same way, Vance [56] narrates the tension produced in the experience of sexuality as a sphere of exploration, pleasure and performance, yet also how this experience can lead in turn, to helplessness, repression and risk of sexual violence.

Narratives with their own emphases, (in)consistencies, silence and oblivion are connected to the possibilities of enunciation of women and the social impact of their experiences. Silences are pervaded by fear, embarrassment, and in the social sense, women stop talking. Soriano [57] states that the proportion of sexually assaulted girls is 10% higher if compared to boys. These results have been replicated in different samples, revealing a higher incidence of sexual assault in women than in men [58, 59], with an increased risk for sexual abuse and assault in late adolescence [59].

It follows that in the case of girls, most of the times, the assailant is someone in their immediate environment and in 70% of the cases the assailant is a close relative, while in boys the assailant is usually a stranger. This fact allows boys to defend themselves, run, hate or despise the assailant as a means of protection akin to war situations where the enemy is perfectly defined. When there is an attachment, kinship or friendship relation between the assailant and the victim, as it happens with girls, there is hardly a way to that defence. Silence reflects how gender-based stereotypes work. Kurvet-Käosaar [60] illustrates this fact in his work on autobiographies by Baltic women during the Stalinist regime. It addresses the difficulties in reporting, giving testimony, considering their limits of self-representation, particularly with issues socially tabooed, such as sexual violence.

With regard to words, as stated by Bertaux-Wiame [61], there are differences both in the way women and men narrate and in the signification of the narration. Women recall the events in a different way, and in more detail, they bind the act of narration to their social experience (family and community networks); thus, they tend to narrate about others [62]. They express feelings, and they conceive fear from everydayness, therefore granting the testimony a special meaning. This is justified by that time in most women is organized according to reproductive events and a different learning process for the emotional [62].

When women speak, they not only do so through words. The work of Kimberly Theidon [63] shows the great variety in response to traumatic experiences and stressful events. In her research on women who had been sexually assaulted and raped by the government forces in Ayacucho (Perú) during the internal war that shook the country, several women asked her: “Why should we remember everything that happened? To martyr our bodies –nothing more?” In these communities, the language of memory is corporal, and women carry the burden of pain and suffering in their communities. This research describes the belief that sorrow can be transferred to the child through breast milk. With the term la teta asustada (the frightened teat), the researcher sought a way of capturing how the powerful negative emotions alter the body itself and how through blood in utero and breast milk (the milk of sorrow and worry) they could transmit this sorrow to their babies. In this division of emotional labour, women embody the history [64].

According to Cyrulnik [65], two shocks are required to cause trauma: a shock in reality (damage, humiliation, loss) and a shock in the representation of reality, that is, in what others say about the person after the assault. Sabine Dardenne, kidnapped in 1996 by a paedophile, stated that she later wrote her story as a means of retrieving her story from under the media spotlight, to express her pain, to put it out and to prevent judges from granting shorter sentences for good conduct to paedophiles [65]. Other women, such as the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo, continue with demonstrations as a reminder, for social recognition and state reparation.

5.3 Trauma and Care

The acknowledgement of sociocultural factors is determining the way the problem may be seen and nested and consequently determines the subsequent approach [66]. Thus, these studies provide sex-disaggregated reference data, but the aim in this data collection should be to further elucidate what elements determine such outcomes. Eliana Suárez [67] compiles and questions some of these statements. For instance, several studies suggest that women are more likely to suffer PSTD than men. One may wonder to what extent can this data be related to differences between women and men in emotional and biological response to interpersonal traumatic events or rather consider that such data is mapping the high incidence of gender-based violence. Some other issues must still be addressed, such as the possible overrepresentation of women in the diagnosis of PSTD due to the gender differences in care-seeking behaviour after exposure to a traumatic event. At the same time, one may consider that gender intersection with factors such as disability, poverty, discrimination and ethnicity could be the triggering cause for the higher vulnerability of women to PSTD. But one point is clear: the literature has shown that some sociodemographic and cultural factors, such as being a woman, ethnicity, living in a low-income neighbourhood, lower education level and direct exposure to interpersonal violence are factors directly associated with a higher risk for the development of psychopathology. Moreover, the risk is greatest when we introduce a traumatic experience into the equation.

Sometimes, being sick or suffering is not enough to be cared for or assisted. It has to be socially accepted that the person needs to be cared for. The decision whether to care for or not is based on the societal expectancies in the group and case given. The decision to care for and assist depends on global criteria through which communities construct the situation basing on their past experience, their collective appropriation thereof and the resources available to them [68].

The hegemonic masculinity model [69] constitutes a hindrance in men’s health given that due to their different way of configuring, dealing and solving their health issues, it blocks the access to care services. Men have been socialized to be active, in control, defensive and strong, look after themselves, endure pain, use their body as a tool and never ask for help and cope. This is a model that encourages self-sufficiency, recklessness, competitiveness or omnipotence. It also requires undergoing certain testing to prove they are on their way to manhood. The predominance of the mainstream male education reinforces the idea that care and self-care are feminine, while values such as strength, courage and boldness are considered masculine. The accident rate and the disproportionate prevalence of men in the suicide rate illustrate this hypothesis [70].

Furthermore, the predominance of a cultural ideology based on “the feminine as the vulnerable” has contributed to reinforce such way of looking at and deem women’s body and health. As an example, in 2017, a polemic came to public attention related to the meaning “weak sex”. This term was defined by the DRAE as “refers to women”, and, in contrary, “strong sex” was defined as “a group of men”. The Real Academy of Language (DRAE) had to modify the meaning as the polemic brought to light in different social media.

Societal attitudes, particularly the low status of women, also play a significant role in hindering women from getting the care that they need [19]. Sometimes this social construction implies that males’ complaints are taken more seriously, while in the case of women, there is a tendency of looking for psychosomatic explanations for their complaints. Some studies have focused that women tend to have more help-seeking behaviours or attitudes than men [71].

Moreover, as stated by Sau [72], in most of the cases, traditional psychotherapies not only had failed in providing suitable answers to women affected by gender violence, but also they had reinforced misogynist myths and, therefore, condemned women to solitude and despair, when these women paradoxically turned to psychotherapy to obtain relief [72].

Complex phenomena need to be observed and constructed in a transdisciplinary integrated way, taking into account the dialectical relationship underlying in the diverse constitutive dimensions of humanity (biological, psychological, social, cultural, etc.). The intended outcome of such a framework is an approach to the social context in the traumatic event, providing a more comprehensive vision of individual and social pain. A historical overview shows us how the trauma paradigm has been directly linked to social movements such us pacifism and women’s rights movement. Therefore, one of the current challenges is to consider the elements that have been sidelined and engage in social justice underlying in traumatic events.

6 Risk Factors for the Development of Psychopathology Following Traumatic Experiences

As described before, potential reactions following a traumatic event can vary across individuals, presenting a variety of symptoms such as increased emotional symptoms (those involving anxiety, irritability, anger, hopelessness or emptiness), somatic symptoms (energy impairment, dizziness, tinnitus or blurry vision) and other symptoms like sleep difficulties [73].

Recent studies exploring the prevalence of traumatic events in the general population showed rates from 28 to 90% [73]. When considering differences presented by gender, some studies have focused that there are differences related to the inner experience of the traumatic event. Psychological trauma can have devastating consequences on emotion regulatory capacities. Indeed, women, as compared with men, evaluated traumatic events more negatively (for all types of trauma), and the relationship between trauma and mental disorder symptoms was also stronger in women [74]. In the case of PTSD, this relation is even more deeper and has been associated regardless the diagnosis criteria, population or methodological variables [75].

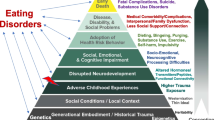

During the last decades, the study of traumatic events related to the risk for the development of psychiatric disorders has emerged. Since that, the presence of traumatic events has been associated with an increased risk for several mental disorders, such as anxiety disorders, eating disorders, depression, PTSD and psychotic disorders [76,77,78,79,80]. Some studies have focused on the evaluation of three categories of risk factors for the development of psychopathology: pre-traumatic factors (including sociodemographic and biological factors, such as age, gender, race, education and predisposing biological factors), peri-traumatic factors (including duration, severity or perception of traumatic events) and post-traumatic factors (access to social network resources and cognitive and physical activities) [73]. Analyzing those factors by gender, they reported more traumatic experiences in males, but despite this, females are exposed to more sexual trauma and are more likely to develop PTSD.

In fact, abuse and PTSD share some common symptoms: intrusive and unpleasant memories, dissociations and flashback sequences. However, a common feature in abuse is the presence of patterns revealing a direct attack to corporality, expressed in different forms: in its pleasure receptor functions; in its capacity of intimacy, conception and nurture; in fully complying the self and other’s biological destiny; and in the creation of meaningful relationships based on body privacy [81].

Recent studies have provided robust evidence of the association between childhood trauma experiences and the development of a wide range of psychiatric disorders [76, 77]. As seen before, many of the psychiatric disorders that have been linked to adversity in childhood, for instance, depression and anxiety disorders, including PTSD, show in general higher prevalence among adult women compared to men of the same age [81, 82].

Frequently, those manifestations are usually hidden under the expression of dissatisfaction, and in some cases submission and subjection, through physical pain. The biography of these women is inscribed in the body and its pains, wherein lies a possible identity conflict. Only through this overabundance of the body is it possible to move beyond the severe and disciplining domain of the reason in order to acquire “consciousness through pain” [83].

The relationship between the risk for the development of psychosis and childhood trauma has been proposed. A growing number of methodologically sound studies have examined the exposure to child maltreatment (i.e. sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional/psychological abuse and neglect), peer victimization (i.e. bullying) and experiences of parental loss and separation as risk factors for psychosis and schizophrenia [84]. A meta-analysis published in 2012 evaluating the association of childhood trauma and psychosis found that trauma was significantly associated with an increased risk for psychosis with an OR = 2.78 (95% CI = 2.34–3.31) [84]. Moreover, this relationship has been associated with a more symptom severity of schizophrenic-positive symptoms (hallucinations and delusions) and also with the severity of childhood neglect with the presence of negative symptoms [85].

In fact, children who have been traumatized do not fit the criteria for PTSD. Those kids frequently are tagged as aggressive or suspicious, receiving diagnoses such as “oppositional defiant disorder” or “disruptive mood dysregulation disorder”, among others [86].

Considering the possible effects that could cause a continuous exposure to such a traumatic event during the childhood, it is not rare that individuals present somatic and physical manifestations. A study published by Waldinger and colleagues [87] shown that in the case of women, childhood trauma influences adult levels of somatization by fostering insecure adult attachment. Adult victims of sexual abuse see their bodies alienated, as a place owned by other, a settlement for the other, as if other person articulated their limbs [81].

Janet [30] hypothesized that memories of the traumatic event that are stored outside the person’s awareness may contribute to dissociation and somatization in the form of hysteria. Along these lines, Van der Kolk [86] advocates the consideration of dissociation, somatization and other affect regulation disorders as late-emerging manifestations of trauma. The link between trauma, dissociation and somatization is empirically supported. In fact, Pribor, Yutzy, Dean and colleagues [88] found that 90% of the women with somatization disorder have a history of physical, emotional or sexual abuse, and 80% of them had a history of some form of sexual abuse.

It is common they express discomfort towards their bodies—dispossession: “I know that somehow this body is mine, but I don’t feel it as such” [43]. In Freud’s words, unheimlich, this literally means “not-at-home” and was translated as unfamiliar, uncomfortable and eerie. James Chu [44] notes that abuse survivors tend to be ambivalent about self-care, and they tend to neglect in basic aspects of their physical health.

Psychiatrist Roland Summit explained in 1988 that every society, not only the directly affected, protects the secrecy of sexual abuse of children. In the same way as the victim is silenced, forced to self-punishment, dissociation and identification with the aggressor, as a society, we are inclined to unthinkingly deny the facts. Jennifer Freyd insists that there are many social interests in children abuse not being revealed and consequently, a great difficulty to discover the real figures [3].

Yet, as Pat Odgen comments, we cannot learn to take care of ourselves if we are not in contact with the needs and requirements of our physical self: our physical identity, our bodily identity and what we physically are [89]. This invasion of corporality at early ages is associated with multiple mental disorders in adulthood in the form of depression, anxiety, substance abuse, self-harm, multiple somatization, borderline personality and post-traumatic stress disorder, among others. It is not surprising that these children use their bodies to release tension and manifest their impulses through self-harm [43]. There are findings that suggest that trauma and sexual abuse, more than being linked to a specific disorder, constitute a nonspecific risk factor for psychiatric morbidity [7]. On the basis of these results, it seems clear that the experience of such a traumatic event marks a major shift in the experience and perception of the people’s inner world.

7 Psychopathologic Manifestations Through the Female Body: Homo Dolorous (Somatization) and Self-Harm

Powerless, weakness and silenced. Structural violence directly or indirectly against female identity has led to an individual (identity) subjectivity shaped in a corporal mask, as an eggshell, filled with obstacles, interruptions, tricks and pain. There is high occurrence of women with painful multi-symptom disorders without a clear organic cause, in which the body symptoms become the emerging of the unperceived: a body complaining to seek affect, support and attention. This situation has been labelled under the diagnosis of “unspecific somatic symptoms”. A body that becomes sick to say no to imperatives, to channel dissatisfaction, and also a body complaining as a possible means to discover other pathways [90].

Somatization, fairly common among women, refers to the tendency of experiencing stress through physic symptoms, bodily concerns and/or experiencing oneself mainly in physical terms. Psychological and physical issues are not integrated. The belief that somatization can be related to trauma as the defensive action of dissociation is not new [7].

Female identity is assimilated to the being-for-others, where the nuclear is the relational and the assigned in the androcentric culture, assuming a secondary role of our own lives and putting aside an intimate story of desire, choices, transcendence and creation. This requires the self to exist, the possibilities of being to be renewed and the possible alterations to be produced.

As described by Judith Herman, the real conditions of women’s lives have been hidden in the private life sphere, creating a powerful barrier where no one can come in, and letting the histories of women’s lives invisible and silenced [2].

7.1 Behaviour in Borderline Patients: Self-Injury

Self-harm behaviour is more prevalent in women than in men, and it is present in 75% of borderline patients, which for the majority of people has an onset in adulthood and is highest between the age of 18 and 24 [91].

According to patients with BPD, the reason for self-harm is in some cases related to numbness: “when we don’t feel anything special, we don’t feel our bodies”. Human beings are in constant need of self-perception even if they fall back again yielded in a quiet lethargy. This intimate experience of physical pain brings them the certainty of the existence of their bodies, the certainty that there is more than emptiness. The way they experience life is outside the traditional forms of managing the body in our culture [38]. The wounds, the blood and the powerlessness denote that they are alive, yet through all this, we can clearly see the expressive function of the body, a pain seeking to be seen and responded. Even though these behaviours alarm relatives and specialists and may be seen as evidence of suicidal intentionality, self-destructive conducts not necessarily represent a connecting factor to suicide.

Many self-destructive behaviours have self-punishment motivations [92] and at times are closely related with an experience of relief in painful and unbearable emotional states [93]. However, the connection between self-harm and suicidal intent is complex.

The occurrence of the self-harm conducts rate, as said before, is in general 75%, but adding conducts like having unsafe sex with strangers or combining alcohol with antabuse may bring the self-harm conducts rate to 90%. In all this, we can see an aggression to the body, a direct act against life, yet it is true that borderline patients put their bodies at risk so they can experience life. And thus, against social boundaries, there is the individual chosen limit [83]. The term self-harm describes an act through which a person intentionally injures or harms themselves. Among the self-injury behaviours, we can find cutting or severely scratching the skin (80%), hitting (24%), burning or scalding (20%), banging the head (15%) and biting (7%) [92]. If the skin is the damp-roof wrapper, the cut provides an outlet orifice, an exit for pain.

A patient wrote about the self-injury impulse: “I want to cut myself. I want to see pain, because it’s the most physical way to show emotional pain. I want to cut myself, cut myself and show it, show it. Taking it out, but taking what? Just pain”.

The intentionality in the self-harming behaviour has been broadly studied. Self-harm has different motivations: to release the pain and tension inside (59%), to punish themselves (49%), to control their feelings (39%), to have control over their bodies (22%), to express feelings of hate and rage (22%) and to find themselves alive instead of feeling numb (20%) [94].

Although the conceptualization of the borderline personality and its causes are still unaccounted for, most of the studies suggest a significant relationship between infantile trauma and borderline symptoms and between childhood sexual abuse and the development of borderline personality disorder [95]. The risk factors that determine borderline patients often include loss, history of sexual and physical abuse, deep negligence or emotional abuse, gender violence witnessing, drug abuse or criminality in progenitors.

Without further analysis on the factors influencing the resultant seriousness in abuse, a research conducted by Silk et al. [94] shows that continued sexual abuse in childhood was the best predictor of serious borderline symptoms, such as parasuicide, chronic helplessness and chronic handicap, transitory paranoia, regression and intolerance to solitude [91]. Furthermore, sexual abuse by parents and emotional negligence in childhood, both involved in the genesis of borderline personality disorder, are closely related with self-harm behaviour [96].

8 The Hidden Wounds: Understanding Biological Epigenetic Alterations Following Traumatic Experiences

The presence of traumatic experiences in early stages of childhood has been associated to a wide number of alterations affecting neurodevelopmental and mental health. Social changes occurring in the environment during the early stages of life have been proven to generate stable changes; most of these changes are affected by a dysregulation of the gene expression through epigenetic mechanisms.

In order to understand the underpinning biological mechanisms involved in early-life stress events, and due to ethical reasons that we will further describe in an upcoming other chapter of this book, these studies are being carried out using animal models. The main objective of these studies in animal models is to understand the basic inner changes produced by long-term effects in signalling paths and in brain pathophysiology. In fact, and despite the controversy associated with research malpractice, studies in animals have been essential to understand underlying mechanisms involved in biomedical research, as in the case in neurodegenerative or in psychiatric diseases [97].

Despite the scientific interest in investigating the effects of social stressor as an interactive influence in human behaviour—an area well studied by sociology and human ecology—the mechanisms underlying cerebral processes are less understood. In fact, and particularly in psychiatry research, the lack of disease biomarkers is a big handicap to understand the mechanisms associated to psychiatric diseases. A biomarker is a characteristic that can be objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of biological or pathological processes [98]. As a result, biological psychiatry research has been introduced as an attempt to understand the biological roots, components and processes of a wide diversity of psychiatric diseases. It also aims to stress its importance for understanding basic processes affected in those diseases.

One of the most important goals for future works in psychiatric research is to find specific biomarkers of diseases to improve the accuracy of diagnosis and, therefore, improve patient outcomes and quality of life. Despite some advances have been made in of other medical areas, such as cardiovascular diseases, psychiatric disorders pose particular challenges.

Nonetheless, we need to consider that psychiatric diseases are complex disorders involving multifactorial genetic and environmental interactions. Psychiatric disorders cannot be addressed by studying individual aspects separately but rather as a complex interaction of multifactorial processes as a whole. The study of psychiatric disorders, in addition to the study of the human being, would require from a holistic global approach that could account for and consider the whole context.

Hence, knowing that human research studies involve such important interactions as sociodemographic and cultural interactions, the translational animal models of stress have provided to control those potential confounding factor that can interact in an ecological set. This set allows researchers control of external factors and enables the study and dissection of basic neurobiological mechanisms at levels that are currently inaccessible to human studies [99].

For this reason, there have been proposed diverse models of early social deprivation and stress-induced models in non-human primates and rodents. Among them, we can find techniques such as deprivation paradigms (i.e. food, water or movement deprivation), exposure to adverse experimental environment, social isolation or fear and anxiety-based paradigms (i.e. exposure to a predator) [100].

Some experimental studies done in animal models have focused on studying the impact of early life stress in genetic or immune alterations. The effects produced by providing maternal stressors during pregnancy range from production of immune inflammatory cytokines and antigens to an increase on the levels of pro-inflammatory genes in the brain and in the intestinal microbiota. That pro-inflammatory activity has been associated with a higher risk of developing a large number of mental disorders [101].

Some studies have shown that maternal separation from its offspring led to a wide range of biological alterations, such as an increased macrophage reactivity or increased core temperature [102, 103]. But one of the most important discoveries is that in both models, there is a common share of a long-term upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines. This data suggests that there is a common link that results from early-life stressors in mother and offspring interaction.

In fact, early-life social environment stressors can induce stable changes that influence neurodevelopment and mental health. Human research studies have explored early-life adversity experiences, also revealing that these experiences can have a persistent impact on gene expression, in the immunity system and in behaviour through epigenetic mechanisms.

Recent studies have also focused in understanding the neurobiology of childhood trauma. In a review published in 2017 by Danese and colleagues [104], it was found that cumulative exposure to childhood trauma was associated with higher levels of inflammation 20 years later and that this association is already detectable even during childhood years. Moreover, they described a set of mechanisms and processes that are affected by childhood trauma exposure; among which we find early-life immunity activation and brain maturity process changes, glial priming changes and finally the alteration of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis in response to stress exposure.

Individuals with a history of childhood trauma show greater amygdala reactivity to emotional stimuli and, consequently, may more often experience activation of the inflammatory response [105]. In higher proportion, they also show reduced HPA axis signalling, and, as a result of the impairment of this inhibitory pathway, they show chronic elevation in inflammation levels. There are other evidences that support the existence of neural dysregulation of essential neurotransmitters, such as monoamines and glutamate. These changes may bring long-term alterations, increasing the risk for the development of psychopathology.

It has been exposed that maternal stress during pregnancy can alter foetal development through the placenta, which in fact regulates the foetal environment [106]. Moreover, this stress exposure has been associated with an increased risk of epigenetic alterations, such is the case of the dysregulation of the HPA axis and consequent DNA methylations. Aberrant DNA methylations have been linked with a wide variety of stress-related psychiatric disorders like depression, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Among several candidate genes, glucocorticoid receptor (NR3C1), serotonin transporter (SLC6A4) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) can be found [106,107,108].

In the light of these results, it seems clear the link between early-life adverse events and epigenetic alterations. The association of childhood trauma to the development of a variety of psychopathological disorders has been extensively proven in the last few years.

To conclude, I would like to add some words by psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk from his book, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma [78]:

Trauma is a complex interaction of the imprint made by the experience in our whole body, mind and brain. The imprint generated has direct consequences for how the body reacts, and how the human organisms manage to survive, producing changes to adapt our mind and brain perceptions and overcome the situation.

9 Conclusions

Sexual abuse and related disorders—such as eating disorder, PTSD, somatization, psychosis and others—are categories in which the body is directly attacked, transformed and frequently negated. In fact, clinical research has proven that the experience of traumatic events can produce a wide range of biological and psychological changes, among them, the development of psychiatric disorders and the alteration of important cerebral processes.

When considering starting therapy with a person who has experienced a traumatic event in the past, the importance of the body should not be disregarded in isolation, as this would mean deficiency and incompleteness. In individuals exposed to trauma, the political, social and relational context in which the traumatic event occurred is also crucial. Similarly, gender perspective is fundamental in addressing these issues with patients. If we disregard this, we will be disparaging patient’s subjectivity.

For the first time in its history, the DSM includes in its last edition a specific section on gender, giving this construct a deep importance when it comes to instilling a new psychopathology. A need on this matter would be to conduct research that furthers understanding the way trauma affects the subjective reality of gender, experienced, naturally, through embodiment.

Trauma occurs in the body and is revealed through the body. It occurs in the private life of women and children, where the silence is imposed by the fear and the stigma. Policies incorporating gender perspective and the empowerment of women against the taboo and silence of such atrocities should be supported by the social and political media. Only through tolerance and respect for every human body where the dignity of human life is embodied, we can hope for better times.

References

Freud S. The aetiology of hysteria. In: The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud, Volume III (1893–1899): Early Psycho-Analytic Publications. London: Hogarth Press; 1962. p. 187–221.

Herman JL. Trauma and recovery: the aftermath of violence—from domestic abuse to political terror. London: Hachette; 2015.

Freyd JJ. Abusos sexuales en la infancia: La lógica del olvido. Madrid: Morata; 1996.

Adichie CN. The danger of a single story. Barcelona: Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial; 2018.

Merleau-Ponty M. Phénomènologie de la perception. Paris: Gallimard; 1945.

Fritz GK. The evolution of psychosomatic medicine. Brown University Child Adolesc Behav Lett. 2000;16(4):8.

Rodríguez B, Fernández A, Bayón C. Trauma, disociación y somatización. Anuario de Psicología Clínica y de la Salud. 2005;1:27–38.

Carlson EB, Dalenberg CJ. A conceptual framework for the impact of traumatic experiences. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2000;1(1):4–28.

Benjet C, Bromet E, Karam EG, Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Ruscio AM, et al. The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychol Med. 2016;46(2):327–43.

Herman J. Trauma and recovery. New York: Basic Books; 1992.

Rosen GM, Spitzer RL, McHugh PR. Problems with the post-traumatic stress disorder diagnosis and its future in DSM V. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(1):3–4.

Pai A, Suris AM, North CS. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the DSM-5: controversy, change, and conceptual considerations. Behav Sci (Basel). 2017;7(1):7.

Hidalgo R. Daño psíquico en las víctimas de violencia de género. Jornada “Actuar frente a la violencia de género”. Pamplona; 2011.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: APA; 2013.

Kilpatrick DG, Saunders BE, Amick-Mc Mullan A. Victim and crime factors associated with the development of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Ther. 1989;20:199–214.

Breslau N. Gender differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Gend Specif Med. 2002;5(1):34.

Pérez P. Trauma, culpa y duelo. Bilbao: Desclée de Brouwer SA; 2006.

Rohlfs I. El género como herramienta de trabajo en la investigación en epidemiología y salud pública. In: Esteban ML, Comelles JM, Díez M, editors. Antropología, género, salud y atención. Barcelona: Bellaterra; 2010.

Esteban ML. Introducción a la Antropología de la Salud: Aplicaciones teóricas y prácticas. Bilbao: OSALDE: Asociación por el Derecho a la Salud; 2007.

Wasco SM. Conceptualizing the harm done by rape: applications of trauma theory to experiences of sexual assault. Trauma, Violence Abuse. 2003;4(4):309–22.

Burstow B. Toward a radical understanding of trauma and trauma work. Violence Against Women. 2003;9(11):1293–317.

Herman J. Trauma and recovery. New York: Harper Collins; 1992.

Burstow B. A critique of posttraumatic stress disorder and the DSM. J Humanist Psychol. 2005;45(4):429–45.

Logan S. Remembering the women in Rwanda: when humans rely on the old concepts of war to resolve conflict. Affilia. 2006;21(2):234–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109905285772.

Kleinman A, Desjarlais R. Violence, culture and the politics of trauma. In: Kleinman A, editor. Writing at the margins: discourse between anthropology and medicine. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1995. p. 712–189.

Janzen JM. Text and context in the anthropology of war trauma: the African Great Lakes region 1993–95. Suomen Antropologi. 1999;24(4):37–57.

Pera C. Pensar desde el cuerpo. Ensayo sobre la corporeidad humana. Madrid: Triacastela; 2006.

Damasio A. Descartes’ error: emotion, reason and the human brain. London: Vintage; 1994.

Damasio A. The feeling of what happens: body and emotion in the making of consciousness. London: Heinemann; 1999.

Janet P. L’évolution psychologique de la personalité. Paris: Éditions Chanine; 1929.

Bowlby J. The mankind and breaking of affectional bonds. I aetiology and psychopathology in the light of attachment theory. Br J Psychiatry. 1977;130:201–10.

Bowlby J. La Separación Afectiva. Barcelona: Paidós; 1985.

Bowlby J. Vínculos Afectivos: Formación, Desarrollo y Pérdida. Madrid: Morata; 1986. p. 90–105.

Bowlby J. Developmental psychiatry comes of age. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:1–10.

Bowlby J. El Vínculo afectivo. 2nd reprint. Barcelona: Paidós; 1990a.

Bowlby J. La pérdida afectiva. Barcelona: Paidós; 1990b.

Bowlby J. Postcript. In: Parkes CM, Stevenson-Hinde J, Marris P, editors. Attachment across the life cycle. London and New York: Tavistock/Routledge; 1991. p. 293–8.

Sáenz M. Cuerpo y Género. In: Martínez O, Sagasti N, Villasante O, editors. Del pleistoceno a nuestros días: Contribuciones a la Historia de la Psiquiatría. VIII Jornadas de la Sección de Historia de la Psiquiatría de la AEN. Madrid: AEN; 2011. p. 101–16.

López-Ibor JJ. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2011;39(3):3–118.

Shinoda J. Sabia como un árbol. Barcelona: Kairós; 2012.

St Just A. Trauma: una cuestión de equilibrio. Un abordaje sistémico para la comprensión y resolución. Buenos Aires: Alma Lepik; 2010.

Valiente C, Cantero D, Villavicencio P. Reflexiones del suicidio en el contexto de violencia de género. In: Fernandez JL, Fuentenebro F, Rojo A, editors. Suicidio. Madrid: Sociedad de Historia y Filosofía de la Psiquiatría; 2008. p. 299–320.

Cantero MD, Villavicencio P. Corporalidad y trauma. In: Fuentenebro F, Rojo A, Valiente C, editors. Psicopatología y fenomenología de la corporalidad. Madrid: Sociedad de Historia y Filosofía de la Psiquiatría; 2005. p. 141–57.

Chu JA. Rebuilding shattered lives. The responsible treatment of complex post-traumatic and dissociative disorders. New York: Wiley and Sons; 1998.

UN Commission on Human Rights. The elimination of violence against women A/RES/48/104. 19 December 1993.

Santiago CD, Wadsworth ME, Stump J. Socioeconomic status, neighborhood disadvantage, and poverty-related stress: prospective effects on psychological syndromes among diverse low-income families. J Econ Psychol. 2011;32(2):218–30.

Baskin-Sommers AR, Baskin DR, Sommers I, Casados AT, Crossman MK, Javdani S. The impact of psychopathology, race, and environmental context on violent offending in a male adolescent sample. Personal Disord. 2016;7(4):354–62.

Sabariego C, Miret M, Coenen M. Global mental health: costs, poverty, violence, and socioeconomic determinants of health. In: Mental health economics. Cham: Springer; 2017. p. 365–79.

Galtung J. Cultural violence. J Peace Res. 1990;27(3):291–305.

Bourdieu P. La dominación masculina. Barcelona: Anagrama; 2000.

James EC. The political economy of ‘trauma’ in Haiti in the Democratic Era of Insecurity. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2004;28(2):127–49.

Távora A. Pensando sobre los conflictos y la salud mental de las mujeres. Área 3. Suppl. Género y Salud Mental. 2003.

Basaglia F. Mujer, Locura y sociedad. Mexico: Universidad Autónoma de Puebla; 1983.

Rosaldo MZ. The uses and abuses of anthropology: reflections on feminism and cross-cultural understanding. Dermatol Sin. 1980;5(3):400.

Hourcade C. Cuerpos fragmentados: Las mujeres y el conflicto con sus cuerpos. Mujeres y salud. Tu cuerpo: personal e intransferible. CAPS. 2008. p. 24.

Vance C. Placer y peligro: explorando la sexualidad femenina. Madrid: Talasa; 1989.

Soriano MJ. El abuso sexual en la infancia y su repercusión en la edad adulta. Mujeres y salud. Monográfico Salud Mental. El trasfondo del malestar. CAPS. 2010. p. 29.

Fedina L, Holmes JL, Backes BL. Campus sexual assault: a systematic review of prevalence research from 2000 to 2015. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2018;19(1):76–93.

Finkelhor D, Shattuck AM, Turner A, Hamby SL. The lifetime prevalence of child sexual abuse and sexual assault assessed in late adolescence. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(3):329–33.

Kurvet-Käosaar L. Vulnerable scriptings: approaching hurtfulness of the repressions of the Stalinist regime in the life-writings of Baltic women. In: Festic F, editor. Gender and trauma: interdisciplinary dialogues. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing; 2012.