Abstract

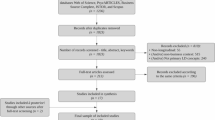

The methodology used to collect and analyse the data for this book encompassed several research methods. A key aim of this book is to share the voices of leaders in Africa, and for that reason, we chose a case study approach as our primary source of data. A range of leadership contexts and diverse leaders were involved—senior and young, male and female. Two main data collection methods were used within each of the case studies: an initial survey and semi-structured interviews. We then used the emerging findings to design a follow-up survey. The aim of this survey was (a) to examine the broader applicability of the case study findings and (b) to help identify and validate the main leadership needs emerging from all data sources.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Research Approach

As explained in Chap. 1, “Introduction”, a key aim of this book is to hear and share the voices of local leaders, and for that reason, we chose a case study approach as our primary source of data. We wanted to include a range of leadership contexts, from both a national perspective and an organizational/sectorperspective, and to gather the viewpoints of senior and junior leaders. Our case studies focus on the following:

-

Leadership in science in Ghana

-

Leadership in business in Nigeria

-

Leading across the generations in Tanzania

-

Leadership in the private sector in Kenya

-

Leadership in ruraldevelopment in Rwanda

Needless to say, these case studies can only provide a snapshot of leadership in the vast continent of Africa, with so many countries and sectors. However, our aim was to gain as rich insights, probing as deeply as possible into the range of experiences and viewpoints of different people within any one context, and then to explore what similarities and differences exist across the various contexts.

Our selection of these leadership contexts was partially opportunistic but also driven by theoretical considerations to acknowledge the diversity of this continent. We sought out local participants who were interested in the issue of leadership and who were keen to work with one of the book authors in developing and co-authoring a case study. Each of them is an African leader who is involved in developing and supporting leaders. Our broad selection criteria were that countries in both East and West Africa should be included and that all the organizational/sectoral contexts should be different. That (along with constraints on the length of the book) led to five case studies being developed.

Having carried out the case studies, we then used the emerging findings to design a follow-up survey for use with a much broader range of people—people working in any sector in any African country who were willing to comment on their perceptions and experiences of leadership and of being helped to develop as a leader. The aim of this survey was twofold: (a) to examine the broader applicability of the case study findings and (b) to help identify and validate the main leadership needs emerging from all the data sources.

2 The Case Studies

Two main data collection methods were used within each of the case studies: an initial survey and semi-structured interviews.

2.1 The Initial Survey

The aim of the initial survey was to collect some preliminary data that would inform the design of the interview questions. The content of this initial survey was drafted on the basis of discussions with leaders in Kenya and Tanzania during the early stages of the project. From these discussions, it became apparent that the following issues were important to the people concerned:

-

Perceptions of hierarchy

-

Leadership styles and the vocabulary to talk about them

-

What it means to be a “good leader”

-

Managing challenges, such as change and innovation

-

Reasons for losing respect for leaders

As a result, we designed the initial survey to cover the following aspects (see Annex A for the full questionnaire):

-

Demographic information on respondents’ nationality, gender, and amount of leadership experience (Questions 1 and 10)

-

Three Likert-type questions on perceptions of hierarchy and leadership styles, probing both attitudes towards these issues as well as people’s experiences of them in the workplace (Questions 2, 5, and 7)

-

A number of open questions to allow for more issues to emerge that could be usefully followed up in the interviews (Questions 3, 4, 6, 8, and 9)

To probe people’s perceptions of hierarchy, we used one of the powerdistance items from the Global Leadership and Organizational Behaviour Effectiveness (GLOBE) study (House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman, & Gupta, 2004), both societypractices (as is) and societyvalues (should be) formats. Regarding different leadership styles and the lack of vocabulary to talk about them, we decided to use Redeker, de Fries, Rouckhout, Vermeren, and Filip (2014) leadership circumplex (see Chap. 2), as it offers a systematic way of conceptualizing and organizing a range of different styles. We used the labels and descriptions of the different styles, but instead of asking respondents to rate the items only in terms of frequency (either in relation to themselves or someone else), as in the original study, we also asked them to make judgements on the suitability of each of the styles for addressing the challenges they were facing in their context. This latter question linked with the previous open item in the survey, which asked respondents to list the challenges they were facing in their contexts.

Information about the respondents is given within each of the case study chapters. Since each case study focused on a specific leadership context, this to a certain extent determined the range of participants asked to complete the initial survey. Moreover, most were contacted via the case study authors’ existing networks. In that sense, the sample was not random. However, the primary purpose of the initial questionnaire was not to conduct a large-scale survey with generalizable results; rather the aim, as explained above, was to gain some preliminary findings which could feed into the planning of the interviews.

The survey was hosted on SurveyMonkey and links to it were distributed by email to the authors’ networks. When sufficient responses had been acquired, the full set of responses was exported from SurveyMonkey into Excel and analysed further by grouping the answers according to common keywords.

For each batch of case study survey results, the Likert-type items were analysed in the following way. The responses to the question on perceptions of hierarchy were plotted on a matrix, with ratings of perceived practice shown on the x-axis and ratings of personal preferences/expectations shown on the y-axis, as shown in Fig. 5.1. The quadrants shaded green represent broadly acceptable situations for respondents whose responses fall there, in that their practice ratings are similar to their preferences or expectations. The quadrants shaded red represent situations that are broadly more problematic, in that people’s experiences in practice are different from their preferences. When respondents’ ratings of their preferences or expectations are identical to their ratings of their experiences in practice, their scores will fall on the diagonal. The closer people’s scores are to the diagonal, the more satisfied they are likely to be. The survey findings on perceptions of hierarchy are reported in this way in each of the case study chapters.

People’s ratings of leadership styles are shown on Redeker et al.’s (2014) circumplex. Once again, preference and experience are shown in the same diagram. The concentric circles, numbered 1–6, indicate both the degree of commonness and the degree of suitability. The relative proportion of green shading, amber shading, and red shading indicates the perceived suitability of that style for the given context, with green representing the most suitable styles, amber the average suitable styles and red representing the least suitable styles. For calculating the most suitable styles, the ratings 5 and 6 of the Likert scale were averaged, for the average styles the scale rating 3 and 4 were averaged, and for the least suitable style the Likert ratings for 1 and 2 were averaged. The mean rating of the frequency of occurrence of each type of leadership style is also shown on the circumplex, using blue dotted lines. An example is shown in Fig. 5.2.

The responses to the open questions were exported to Word and categorized/grouped into themes. Some of these themes were the same as the key concepts used in the coding later. On the one hand, this data then fed into the design of the semi-structured interviews; on the other, they were used to complement the interview data, adding occasional further insights and examples.

2.2 The Interviews

Following the collection of the initial survey data, an interview guide was developed (see Annex B). Seventeen indicative questions were listed, covering the following broad aspects of leadership:

-

Personal narrative about becoming a leader

-

Beliefs about leadership and experiences of it

-

Challenges and successes of being a leader

-

Developing and improving as a leader

-

Perspectives on leadership in Africa

The interviews were all carried out by the case study authors in English or in the local language. In some cases initial interviews were conducted jointly for trainingpurposes. The localcollaborators were given advice on conducting interviews, including the need to be flexible and not to follow the indicative questions in a slavish manner.

In terms of the interviewees, a diverse group of participants was sought, especially both senior and young participants, but also both women and men, and this was successfully achieved. Understandably, though, participants to a certain extent self-selected, as those with a keen interest in leadership volunteered to participate and generously gave up their time to do so. Each case study ultimately involved a group of around 40–50 leaders, usually with the majority completing the initial survey (around 20–30), plus around 10–20 interviewees.

The majority of the interviewees were different from the people who completed the initial survey, although in a small number of cases (indicated in the case study chapters) individuals participated in both. Each interview took between one and two hours to conduct. While the interviews touched on many of the same issues as the initial survey, the goal here was to obtain rich, in-depth data. Participants were asked to provide insights into their leadership experiences, to recount specific personal experiences in being and becoming a leader, and to talk about specific challenges and successes.

Notes were taken during the interviews, which were later transcribed. Each interviewee then reviewed the draft transcript and made small amendments if necessary. They were also asked to pick a pseudonym so that their stories could be presented anonymously if needed.

The interview transcripts were then imported into the R Qualitative Data Analysis (RQDA) software. Conventional content analysis was used to analyse the interview transcripts, since a case study describes a phenomenon in which existing theory or research literature is limited. Text mining of the transcripts yielded a list of terms that were used frequently. Then the transcripts were read through numerous times to identify key themes (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). This ultimately allowed five categories and 15 codes, along with names for the categories, to flow from the data. The category and code structure is presented in Annex C. The case studies have been written up and organized around these five themes and keywords.

The coding was done by one of the chapter authors and, during the write-up of each of the case study chapters, the respective material was used by each of the case study co-authors. The code attribute function in RQDA was used to explore and report on any associations between codes and attributes, such as age, gender, and in some cases type of organization. As stories are powerful in conveying a message, extensive personal leadership experiences from the interviews and the initial survey are presented in the case study chapters (interview comments in text boxes and survey comments in italics) in order to provide rich data to illustrate the findings.

As explained above, each case study relates to a specific country and leadership context or sphere. However, to ensure coherence across the chapters, each case has been prepared by combining the initial survey and interview data and using the following framework:

-

1.

Introduction

-

2.

Context: Specific context of the case study and background

-

3.

The case study data

-

4.

Perceptions of hierarchy

-

5.

Leadership styles and the need for change

-

6.

Leaders’diversity: Impact of gender and age

-

7.

Leaders’ attributes: Perceived qualities of a good leader

-

8.

The roadto becoming a leader: LeadershipDevelopment

-

9.

Conclusions and discussion: Overall conclusions and discussion of new insights on the changes in leadership of today’s leaders

3 Follow-Up Survey

The follow-up survey was designed to explore and validate on a broader scale the leadership issues and development needs emerging from the case studies. Since the case studies focused on just five African countries and were also topic/sector specific within each of those countries, we felt it would be useful to examine the perceptions of a wider range of people in different African countries who were working in a broader set of contexts. We therefore developed an instrument that did not replicate the issues probed in the initial survey, but rather picked up on those that had emerged from the case study research.

Many case study participants commented on the need for a change in traditional leadership styles and expressed a desire for personal self-development as a leader. So, we designed the survey around these aspects, using the framework shown in Fig. 5.3.

In other words, we decided to probe five aspects of personal LeadershipDevelopment, plus routes to developing as a leader:

-

Self: Me as a leader

-

Employee: Me and the employees I am responsible for

-

Team: Me and my team

-

Organization: Me and my organization

-

Community/society: Me and the wider community/society

-

LeadershipDevelopment: Routes to becoming a leader

With the help of the case study data, along with insights we had gained from previous research, we drafted five to eight items to probe each of the constructs listed above. Building on the design of the Global Education Profiler (GEP), developed by Spencer-Oatey and Dauber (2015) at the University of Warwick, we asked respondents to answer each of the items in two ways:

-

“Importance to me” (IMP) (i.e. how important it is to you to practice or experience this at work, e.g. for carrying out projects well and/or for people’s well-being)

and

-

“Frequency of occurrence” (FOO) (i.e. how often you actually practise or experience this in your workplace)

This enabled us to examine not only the issues of importance to the respondents, but also the size of the gap between the importance they attach to something and the extent to which they are experiencing it in their context. This information then enables prioritizing of the development issues.

The draft items were piloted with a small number of people, including with several African respondents, and then near-finalized. This resulted in a total of 33 items, each to be answered in two ways, along with an open question at the end so that people could make any comments they wished about the survey and/or their experiences of leadership. The survey also included several demographic questions: gender, age, nationality, amount of leadership experience, and work context. (See Annex D for a copy of the English version of the survey.) After this, a French version was commissioned, with back translation used to ensure equivalence of meaning. Decentring led to some minor tweaking of the English version. (See Brislin, 1970, for an explanation of the concepts of back translation and decentring.)

Once the survey had been finalized, it was entered into Qualtrics software and formatted so that it could be completed on a mobile as well as on a tablet or desktop. Invitations to participate in the survey (with links to the English and French versions of the survey) were sent out to a range of leadership networks in Africa. In addition, invitations to participate were posted on LinkedIn and professional websites such as eLearning Africa, and individualized emails were sent to other professional contacts, asking for their help both to participate and to forward the link to other contacts. We particularly tried to involve leaders from African countries not represented in the case studies. A forced-choice item on nationality prevented respondents continuing with the survey if they were not from Africa. In total, 240 completed questionnaires were received, with respondents from 31 different countries in all five regions of Africa (North, West, Central, East, and Southern).

Analysis of the data followed the procedures used by Spencer-Oatey and Dauber (2019) for analysing Global Education Profiler data, since the design of the tool was comparable. A matrix was used for presenting the findings visually, similar in principle to that used to present the case study initial survey data. However, in this case, the quadrants were labelled. When people’s IMP and FOO scores are both high, this is the most positive situation and so this quadrant is labelled “flourishing”. When people’s IMP scores are high but the FOO scores are low, this is a problematic situation because of the failure to meet people’s expectations/desires, and so this quadrant is labelled “unfulfilling”. When people’s IMP scores are low but FOO scores are high, the context is positive in terms of actual experiences, but people’s aspirations are low. This quadrant is labelled “nurturing”. The fourth quadrant is the most problematic in terms of developingglobal leaders because people not only attach low levels of importance to it but also experience it very little. This quadrant is labelled “limiting”. Figure 5.4 illustrates this matrix and its component quadrants.

Details of the analyses and the findings used with the follow-up survey are presented in Chap. 11. First, though, we present our case study findings in turn.

References

Brislin, R. (1970). Back translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1, 185–216.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (Eds.). (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations. The GLOBE study of 62 societies. London: Sage.

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288.

Redeker, M., de Fries, R. E., Rouckhout, D., Vermeren, P., & Filip, d. F. (2014). Integrating leadership: The leadership circumplex. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(3), 435–455.

Spencer-Oatey, H., & Dauber, D. (2015). Global Education Profiler (GEP). Retrieved from www.warwick.ac.uk/gep

Spencer-Oatey, H., & Dauber, D. (2019). Internationalisation and student diversity: Opportunities for personal growth or numbers-only targets? Higher Education. Online first. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00386-4

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Jordans, E., Spencer-Oatey, H. (2020). Methodology. In: Developing Global Leaders. Palgrave Studies in African Leadership. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14606-1_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14606-1_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-14605-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-14606-1

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)