Abstract

The main purpose of this chapter is to analyze the theoretical relationship between globalization and institutional quality and the empirical analysis of this linking in developing countries. For this aim, this chapter seeks to answer three main questions: (1) How do institutions affect globalization (trade openness)? (2) Can the economic globalization and trade openness cause institutional changes? If the answer is positive, does globalization lead to an improvement in the institutional quality or its deterioration? (3) Is there any causal relationship between globalization and institutional quality in developing countries?

To answer these questions, we use analytical-descriptive methods and econometric methods including Granger-type causality test based on panel vector error correction model (PVECM).

The theoretical findings of this chapter show that the good institutional quality via various channels affects the volume, structure, and composition of the trade. Also, economic globalization may improve (or deteriorate) the quality of institutions, but the kind and the extent of its influence depend on the type of institutional system and institutional structure of countries.

The descriptive analysis of data (status of globalization and institutional quality) in developing countries showed that the trend of economic globalization is not favorable in comparison with the world trend. In addition, compared to both three dimensions of globalization and the world as a whole, it presents an unfavorable situation. On the other hand, the position of institutional quality, in particular the quality of regulation and the effectiveness of governments (of the vital factors of trade expansion), has the worst situation. The results of Granger-type causality test showed that there is no causal relationship between economic globalization and legal-economic institutions (such as the rule of law and government effectiveness) in the short term, but there is at least one causal relationship in the long run. This relationship with the index of the rule of law is bidirectional and with other indexes is unidirectional. Also, the findings of this study show that in the short and long run, political globalization is the cause of political institutions (political stability and voice) and social globalization is the cause of social institutions. Therefore, the globalization view of institutional change can be cautiously supported.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Globalization has economic, political, and social dimensions. Economic globalization can be measured through trade openness and financial openness. Trade openness is related to the flow of goods and services. Goods and services, especially in the trade sector, have different categories. On the other hand, institutions have various types. Generally, institutions are divided into political, economic-legal, social, and cultural institutions. Each of these institutions, particularly the economic-legal institutions, has a variety of ranges.

The trend of economic globalization in developing countries is not favorable in comparison with the world trend. On the other hand, the position of institutional quality, in particular the quality of regulation and the effectiveness of governments (of the vital factors of trade expansion), has the worst situation.Footnote 1

Regarding to the status of globalization and institutional quality, various questions can be proposed. An important question faced by developing countries is (1) globalization (trade openness) is influenced by which (institutional and noninstitutional) factors? What are the barriers ahead of it? In this regard, the key question is that what is the effect of institutions on globalization (trade openness)? On the other hand, institutions (both domestic and international) change over time. Another important question, especially for developing countries, is that (2) how do institutional changes happen? Does globalization play a major role in institutional changes in developing countries? Does globalization improve institutional status or lead to its degradation? According to the two previous questions, another important question will be proposed. (3) Is there any causal relationship (theoretically and empirically) between globalization and institutional quality in developing countries in short run and long run? If this relationship exists, how is the direction of causality?

There are various theoretical and empirical literature which are answered to the first and second questions, but negligible attention is given to the third question (especially theoretically).

In the vast majority of studies, the causality between these variables is assumed as unidirectional, and this relationship is investigated theoretically or empirically (for one or more countries). For example, in Francois and Machin (2013), Alvarez et al. (2018), Tang (2012), Araujo et al. (2016), Palangkaraya et al. (2017), Czinkota and Skuba (2014), Gani and Clemes (2013, 2016), Levchenko (2004, 2007), Feenstra et al. (2013), Moenius and Berkowitz (2011), Yu et al. (2015), De Groot et al. (2004), Desroches and Francis (2006), and Aziz et al. (2018), the causality direction from institutions to globalization is assumed. In these studies, the impact of institutions on globalization has been investigated. Also in Do and Levchenko (2009), Levchenko (2008, 2012), Bergh et al. (2014), Bhattacharyya (2012), Stefanadis (2010), Kant (2016, 2018), Muye and Muye (2017), Potrafke (2013), and Young and Sheehan (2014), the causal direction from globalization to institutions is assumed. In these studies, the impact of globalization on institutions has been investigated. In many of these studies, the regression models and data from various countries are used, and different results have been achieved.

In few studies the causal relationship between one dimension of globalization and one type of institutions is examined. For example, Nicolini and Paccagnini (2011) investigated the causal relationship between the ratio of the trade flow on GDP [trade openness] and the political rights and civil liberties [political institutions] for 197 countries, and they showed that there is no causal relationship between them.

The main purpose of the present chapter is to fill this gap. Therefore, the first contribution of this chapter is investigating this issue that there is a bidirectional causality between globalization and institutional quality, theoretically. Another contribution of this chapter is to test this causal relationship empirically in developing countries. In this regard, after a comprehensive review of the literature and explaining theoretical relationship between economic globalization and institutions, the causality between (economic, social, and political) globalization and (legal-economic, social, and political) institutions in developing countries has been tested.

Empirical results based on the data during 2001–2015 showed that there is no causal relationship between economic globalization and legal-economic institutions in the short run but at least there is one causal relationship (from globalization to legal-economic institutions) in the long run. Moreover, social globalization has a unidirectional causal relationship with social and political institutions (from globalization to social and political institutions) both in the short and in the long run.

The present chapter consists of six sections. The remainder of this chapter is organized as follows. The second section is devoted to theoretical foundations. In this section, the framework of analysis, the concepts and indexes of measuring the various dimensions of globalization and types of institutions, the impact of institutions on trade, institutional changes through trade, and bidirectional causality between globalization and institutions are discussed. The third section provides the brief overview of the literature review. Empirical findings regarding the status of globalization and institutional quality and causal relationship between them in developing countries are presented in the fourth section. Section 5 presents the discussion of the study, and the final section is devoted to the concluding remarks.

2 Theoretical Background

2.1 Framework of Analysis

Globalization and institutions are multidimensional and interdisciplinary concepts. To analyze the causes and factors affecting each one, interdisciplinary analysis is required. In order to be able to provide a comprehensive analysis of globalization and institutions and the relationship between them, one should study these concepts from the perspectives of economics, management, sociology, psychology, history, and political science. Nationally it is not possible to provide such an analysis in one chapter and by one person.

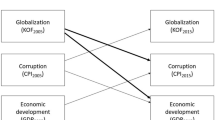

The relationship between formal and informal institutions and globalization is presented in Fig. 1, and the relationship between various dimensions of globalization and various types of institutions is shown in Fig. 2. According to Fig. 1, there is a mutual impact between the local (or national or home-country institutions of the origin and destination country) institutional conditions and the global (or international-wide) institutional conditions in the form of formal and informal institutions and various dimensions of globalization. It is also clear from Fig. 2 that there is a mutual impact between the various dimensions of globalization and the types of institutions. It should be mentioned that it’s not possible to analyze these issues in this chapter. Therefore, in the present chapter the relationship between trade and trade openness (an indicator of economic globalization) and formal economic institutions (such as property rights, rule of law, etc.) theoretically are investigated. The empirical evidence of this relationship in developing countries will be presented and analyzed in a separate section.

2.2 Globalization and Institutions: Concept and Measurement

There are various definitions for institutions.Footnote 2 In general, institutions are arrangements that formed the behavior of part of society and it has impact on it. The meaning of institutional quality is power, consistency, and robustness of the institutions in a country. The institutional robustness refers to the sovereignty, influence, and the real power of institutions. Also, the institutional structure refers to the form of inter-institutional and intra-institutional that can be producer-friendly or rent-seeker/predator-friendly (Renani and Moayedfar 2012: 160–163).

There are various types of institutions, and one may evaluate by various quantitative and qualitative indexes. Some of the quantitative indexes to measure the quality of economic-legal, social, and political institutions are presented in Table 1.

Also, there are numerous definitions for globalization. Globalization is equivalent to integration of the national economies and removing barriers of trade (Stiglitz 2002). This definition is different from the views of sociologists, economists, and theorists of international relations. Each definition refers to the different dimensions and functions of globalization (Mossalanejad 2014: 1–3). The economic, social, cultural, and political dimensions are different dimensions of globalization that are measured by several quantitative and qualitative indexes. Some of these indexes are presented in Table 1.

Economic globalization is measured and analyzed by trade-openness indicators—as the representative of the flow of goods and services—and financial openness or capital flow as the representative of financial and capital markets. Some of the indexes presented in Table 1 focus on both aspects of economic globalization (which is more about trade openness).

2.3 Determinants of Trade

Trade can be classified as trade in goods and trade in services. Also goods are divided into various categories. Some of these categories included:

-

I.

Patentable vs. unpatentable goods (Palangkaraya et al. 2017)

-

II.

Homogeneous vs. differentiated goods (Francois and Manchin 2013)

-

III.

Simple (commoditized products) vs. complex (highly differentiated products) (Moenius and Berkowitz 2011)

Services are also categorized into two: market services (including producer, distributor, personal and communication services) and nonmarket services (including social services such as health, education, and housing) (Gani and Clemes 2013: 297).

Also, the theories of determining factors affecting trade can be divided into two general categories. These categories included:

-

I.

Orthodox views (such as classical Heckscher–Ohlin theory of comparative advantage, Samuelson-Stolper, new trade theory, etc.). In these theories, the main factors or barriers to trade are considered predominant factors such as the income of foreigners and residents of the country, tariffs, quotas, relative price differences, etc. (Gani and Clemes 2016: 512).

-

II.

Heterodox views (such as institutional economists, behavioral economists, etc.). The general view in these theories is that incomplete and asymmetric information and uncertainty in trade cause hidden trading costs and thus lead to increased transaction costs (De Groot et al. 2004: 103).

It should be noted that explaining the views of all theories to identify the factors affecting the trade of goods and services in this chapter is not possible, and according to the title of this chapter, only Heterodox theories and, in particular, the views of institutional economists are expressed.

Also on investing the impact of institutions on trade, the following points should be noticed:

-

I.

Institutional systems (seven types introduced in Fainshmidt et al. 2018).

-

II.

Institutional structure (producer-friendly vs. rent-seeker-friendly structure)

-

III.

Institutional quality (bad vs. good/strong vs. weak/level and distance)

-

IV.

The types of institutions (legal-economic, political, social, and cultural/formal and informal)

In other words, the impact of the level or distance of the institutional quality of the types of institutions in various institutional systems with various institutional structures (rent-seeker-friendly or producer-friendly) on flows, structure, composition, and variety of the goods and services of trade is different. Also these impacts in national and local levels/macro and sectorial level and the origin or destination countries are different. As it is not possible to analyze all the material mentioned in this chapter, based on the above explanation, in the present chapter only the impact of legal-economic institutions (formal institutions) on trade of goods will be discussed.

Legal-economic institutions included contracting institutions and property rights institutions.Footnote 3 Legal traditions, the kind of legal system of the origin and destination countries, regulation of patent, (physical- and intellectual-)property rights, the rule of law, control of corruption, transparency, doing business, etc. are some legal-economic institutions which arguably effect on the volume and composition of trade in goods and services. A good institutional quality will lead to a change in the volume, structure, and composition of trade via various channels. However, the amount of the changes is different in the various institutional systems and various institutional structures. Some of these channels include decreasing rent-seeking, reducing trade monopolies (through tariffs and quotas), increasing long-term profits of trade, reducing barriers of entry (Alvarez et al. 2018), increasing survival in the market of destination countries, reducing informational frictions (Araujo et al. 2016), enhancing trust (Alvarez et al. 2018; Araujo et al. 2016), decreasing transaction costs (Moenius and Berkowitz 2011), forming relative advantage (Francois and Manchin 2013; Levchenko 2004, 2007; Desroches and Francis 2006; Tang 2012; Nunn and Trefler 2014), providing legal security guarantees (Alvarez et al. 2018; Czinkota and Skuba 2014), security of contracts (Nunn 2007; Araujo et al. 2016), and the strengthening of the legal system of the country (Gani and Clemes et al. 2013, 2016).

In the hypothesis of institutional relative advantage (IRA), institutional quality is considered as the source of the relative advantage of the country. According to the hypothesis, in countries with low institutional quality (most of countries in the South), contracts are not completely executed. In such a situation, there is a motivation to expropriate the rights of others. To avoid such a problem, the costs of contract enforcement, the guarantees of security contracts, and property rights should be increased. Therefore, traders, in addition to conventional costs, must also bear the transaction costs.

Also, in countries which have good institutional quality (e.g., good contract institutions) (the North countries), there is a tendency to export relatively capital-intensive goods. This institutional difference leads to the formation of a relative advantage that is known as “institutional relative advantage” (Desroches and Francis 2006: 1; Levchenko 2007: 791–792). Differences in factor endowment, skills of the workforce, contract institutions, etc. are among the factors that may create relative advantages (Tang 2012: 338). A good institutional quality (e.g., contract institutions) will lead countries to find expertise in the production and trade of goods which are institutionally dependent. These goods mostly are relying on the institutions (e.g., the quality of contract execution) (Levchenko 2007: 792). The North countries often specialize in the production and export of these goods, because the productivity of these goods and sectors is higher. Furthermore, it has benefit for the South countries (with weak institutional quality) to prevent production and export these goods to avoid rising costs, because it may weak institutional quality clear in the low efficiency of institutionally intensive sectors.

Generally, the impact of institutions and institutional reforms on the volume and composition of goods can be divided into three categories such as volume effect, compositional effect, and scope effect (Moenius and Berkowitz 2011: 452). Improving the institutional quality increases the exports of complex goods (highly differentiated products) due to the benefits of relative advantage (volume effect), and the combination of exports in favor of these goods and to the detriment of simple goods (commoditized products) changes (compositional effect). Obviously, the improvement of the institutions decreases the international transaction costs and, thus, increases the amount of diversity in the export of complex products (scope effect). So:

Hypothesis 1

Improving institutional quality lead to globalization.

2.4 Globalization View of Institutional Change

Institutions in the viewpoint of the first generation of institutional economists are exogenous and unchangeable, but in terms of the second generation, institutions are endogenous and changeable. From the viewpoint of the second generation of institutional economists, institutions are always changing over time and evolving. These changes are often slow and dull. But incidents such as revolutions, wars, political-social turmoil, and extreme changes in government policies may cause rapid changes in some economic institutions, changes in the political and social structure, and consequently, the quality of existing institutions in the society.

The institutional changes and the reasons of its creation always have been the interest of institutional economists and other professionals. Based on this, several theories have been proposed to explain the reasons for the change in the quality of institutions. These views included:

-

1.

Efficient institutions view or political Coase theorem (PCT)

-

2.

Ideology or the generalized PCT

-

3.

The incidental institutions view

-

4.

The social conflict view

-

5.

Transaction cost theory of institutional change

-

6.

Entrepreneurial view of institutional change

-

7.

Globalization view of institutional change

Here, only the globalization view of institutional change will be explained.Footnote 4 By considering the trade aspect, the main question that this theory seeks to answer is how does trade openness, and under what circumstances, cause changes (improvement or deterioration) of institutional quality?Footnote 5

Trade openness may affect the quality of economic institutions through a variety channels and may lead to changes in the institutional qualities (improvement or deterioration). Some of these channels included:

-

1.

Institutional structure

-

2.

Change of rents

-

3.

Technology transfer

-

4.

Political power and foreign competition effects

These channels briefly are described in the following.

2.4.1 Institutional Structure

In every country, all talents are allocated between productive activities (producer-friendly) and unproductive or destructive activities (rent-seeker-friendly or predator-friendly). If producer-friendly activities overcome the destructive activities, then the economy is producer-friendly, or else, the economy will be rent-seeker-friendly. The overcoming of one activity to another (the status of an institutional structure) depends on the institutional quality of the society. If in a society, economic institutions (such as property rights, rule of law, quality of contract execution, etc.) are weak and the group of rent-seekers politically are dominant, in this case, they prefer to undermine existing institutions and even create weaker institutions to exploit more resources and for more benefits (Renani and Moayedfar 2012: 160–163). The trade and its benefits will cause the size of firms become larger. If the institutional structure of the society is producer-friendly, then the number and size of the productive firms will increase. Productive firms prefer to follow good institutions and strengthen them. Stefanadis (2010), by expansion of the new trade theory in the framework of political economy and in a theoretical model, showed that in a producer-friendly economy, trade causes increase in the ratio of producer compared to the predators. Vice versa, in a predator-friendly economy, this ratio will decrease. Contrary to the Orthodox theories that focus on the characteristics of the country’s trading partners, he relied on the political economy approach and shows that in producer-friendly economies, trade improves institutional quality but in predator-friendly economies, trade conduces into deterioration of institutional quality. These influences will occur through the channel of political economy by influencing on the allocation of talent in a country (Stefanadis 2010: 149). Therefore, it can be concluded that trade openness, dependent on the institutional structure of countries, may have a positive or negative impact on the institutional quality of a country.

2.4.2 Rents

Levchenko (2007, 2008, 2011, 2012) by using the theory of incomplete contracts and in the framework of lobbying game of Grossman-Helpman, in a theoretical model, shows that the main key to institutional changes after the country’s opening to trade is the changes that have been made to rents. According to him, imperfect institutions create rents for some groups (parties), and there is the source of relative advantage in trade. If trade openness eliminates rents, then economic agents will find motivation to improve institutional quality; otherwise, the quality of the institution will be deteriorated.

Contracts in countries with weak institutions are very incomplete. In the context of incomplete contracts, some people earn rents. Rents by themselves are the main reasons for lobbying to create and strengthen institutions which are bad and weak. Also countries may produce and trade institutionally intensive goods. When trade openness occurs in a country and it ventures to export this kind of goods and therefore gain benefits from the relevant rents, then there will be strong motivations toward the deterioration of institutional quality. Otherwise, it will try to improve the status of institutional quality. Therefore, it can be argued that in case of more trade openness with incomplete contracts, some people will get more rents. These people, by having the political power, will try to make weaker institutions to earn more benefits from the trade. In contrast, if the inferior institutions are dominant in the country, then rents are eliminated, and trade openness will lead to improvements of institutional quality. This mechanism for improving institutional quality is described in the study of Levchenko (2012).

2.4.3 Technology Transfer

Some institutional economists, such as North (1981), and Acemoglu et al. (2005) believe that technological progress leads to institutional change. North (1981) demonstrates the capital accumulation as the main causes of the institutional changes in a society, and according to Acemoglu et al. (2005), the political power is the major element of the changes. Undoubtedly, trade and trade openness have impact on the size of market and technology transfer. One of the positive effects of trade and trade openness is that it leads to the transfer of technology, in particular, the skills-based technology. Such an event will increase the share of the middle-income group in society (Bhattacharyya 2012; Acemoglou and Robinson 2006). By increasing the share of the middle-income group, while the political power of these groups compared to the other groups and other classes of society has increased, these groups will be able to set the society institutions including economic institutions (such as the property rights institutions and contract institutions) to their own benefit and will create a change in economic institutions. This change can be in favor of good or bad institutions. Therefore, trade and trade openness can cause improvement or deterioration of the institutional quality.

2.4.4 Political Power and Foreign Competition Effects

Manufacturing firms in a country can be divided into (large- and small-)exporting and non-exporter firms. If a country follows autarky, the distribution of profits due to the production and the trade of manufactured goods between these firms will be somewhat equal, and the firm’s share from market remains intact for a long period of time. But when trade openness occurs, the productive firms grow, and the small firms will be eliminated. Indeed, the access to the foreign markets will cause the distribution of profits between these firms unequally. While there is trade openness, the productive firms will be larger and will prefer to create and strengthen good institutions to remain in the international economy, and the performance of these firms will improve the institutional quality in the country. This effect is known as foreign competition effect.

On the other hand, entering to the international trade will cause larger firms have more export and have more political power compared to the autarky. These firms, in order to gain benefits of political power and the authority of decision-making, create institutions and strengthen them for their benefits. These institutions often act as bad institutions. As a whole, it can be concluded that, in such a case, the trade openness will lead to a worse institutional quality. This effect is known as “political power effect” (Do and Levchenko 2009: 1491).

The overall effect of trade openness on the institutional quality depends on the overcoming effect of foreign competition on the strength of political power (or vice versa). If the foreign competition effect is dominated, then the trade openness will have a positive impact on institutional quality and will lead to their enhancement. Otherwise, the trade openness will worsen and deteriorate the institutional quality.

Whenever a country is large or has a small share in the production and trade of goods that are rent-seeker-friendly, the foreign competition effect will be dominated. Conversely, when a country is small or has a relatively large share in the trade of such goods, the political power effect will be dominated (Ibid, p. 1491). So:

Hypothesis 2

Globalization causes institutional quality.

2.5 Institutional Change and Globalization: A Causal Relationship

Trade is a mutual relationship between business parties, and it needs appropriate rules of the game (institutions). The good and appropriate game rules such as trust (of the trade parties to each other) will lead the volume and composition of trade to rise. In such condition, the required opportunity for the economic globalization of the countries will be provided. The proper institutional system, the production-friendly institutional structure, and the good institutional quality are among the other requirements of globalization in all the economic, social, and political dimensions. Therefore, as shown in Sect. 2.3, institutions and institutional changes are the causes of trade openness and, in general, the causes of globalization.

On the other hand, the globalization of the economy depending on the institutional structure (rent-seeker-friendly or producer-friendly) of countries, technology transfer, changes in the rents’ amount of countries, and the effect of political power and the effect of external competition ultimately can improve institutions and/or provide the area for the deterioration of institutions. Therefore, as shown in Sect. 2.4, globalization can lead to creating institutional changes or making new institutions. So:

Hypothesis 3

There is a bidirectional causality between globalization and institutional quality.

Furthermore, its possible that no causal relationship between globalization and institutional quality exists. So:

Hypothesis 4

There is no causal relationship between globalization and institutional quality.

3 Literature Review

As mentioned in the second section of the present chapter, the impact of institutions on trade, and also the impact of globalization (trade openness) on the institutional changes (the improvement and deterioration of the quality of institutions), as theoretically, is ambiguous, and it depends on various conditions. There are numerous empirical studies in which the impact of various types of institutions on the trade in different countries, different trade blocks, different time horizon, with different types of data, and different econometric methods are investigated. In this section, we briefly review the relationship between economic globalization and institutions.

In few studies (Gani and Clemes 2013, 2016), the impact of various kinds of institutions (i.e., legal systems) on the trade of service has been emphasized. Gani and Clemes (2013) investigated the impact of the domestic trade environment on the total trade services, and Gani and Clemes (2016) focused on the trade of insurance and financial services, and they concluded that enhancing the legal system (rule of law and regulatory quality) in the OECD countries led to an increase in the export of services, especially the financial and insurance services. But there are many studies on the impact of various types of institutions on trade of goods.

Several scholars have focused on the various types of goods such as homogeneous and differentiated goods (e.g., Ranjan and Lee 2007; Feenestra et al. 2013) and simple and complex goods (e.g., Moenius and Berkowitz 2011). The majority of existing studies have focused on the total volume of export of goods. Meanwhile, several scholars (e.g., Tang 2012; Aziz et al. 2018) have studied the sectoral level, and others (e.g., Feenstra et al. 2013) have considered the provincial level. Some studies (e.g., Yu et al. 2015; Manolopoulos et al. 2018) compared the effects of formal and informal institutions on export activities and bilateral trade patterns, but in most other studies only formal institutions have been considered.

In some studies (e.g., Aziz et al. 2018), the impact of political institutions has been intended, but a large number of studies have focused on the impact of legal-economic institutions. In this area, we can point to the studies of Araujo et al. (2016), Palangkaraya et al. (2017), Czinkota and Skuba (2014), Gani and Clemes (2013, 2016), Baccini (2014), Francois and Manchin (2013), Tang (2012), Levchenko (2004, 2007), Feenstra et al. (2013), Yu et al. (2015), De Groot et al. (2004), and Desroches and Francis (2006). The common findings of all these studies indicate that contracting institutions and property rights institutions are important factors in the expansion of production and trade.

Moreover, there are numerous theoretical and empirical studies which have investigated the impact of globalization on institutional quality. In this area we can point to the studies done by Levchenko (2007, 2008, 2012), Do and Levchenko (2009), Bergh et al. (2014), Bhattacharyya (2012), Stefanadis (2010), Kant (2016, 2018), Muye and Muye (2017), Asongo and Biekpe (2017), Potrafke (2013), Young and Sheehan (2014), and Long et al. (2015). Among these scholars, studies of Long et al. (2015), Muye and Muye (2017), and Kant (2016, 2018) probed into the foreign direct investment (FDI) and financial aspect of globalization. Study conducted by Young and Sheehan (2014) is related to the foreign aid, and Asongo and Biekpe (2017) have focused on the social and political institutions. But in other studies, the economic aspect of globalization and economic institutions are posed.

Several studies such as Levchenko (2007, 2008, 2012), Do and Levchenko (2009), and Stefanadis (2010) are also theoretical. Do and Levchenko (2009) and Levchenko (2007, 2008, 2012) in the theoretical models based on the doctrines of political economy showed that the trade openness under certain conditions can lead to the improvement of the quality of institutions and, in other circumstances, degrade the improvement of institutional quality, and therefore, it is not possible to determine a conclusive outcome. Bergh et al. (2014), by empirically using data from 109 countries during 1992–2010, showed that the direction of this effect is dependent on the level of economic development of countries (poor or rich). Furthermore, they concluded that trade openness has a positive impact on institutional quality in rich countries and has a negative impact on poor countries.

Bhattacharyya (2012) after using data of 103 countries from 1980 to 2000 highlights the impact of trade openness on the quality of institutions. Other findings of this study are that this result relative to the different criteria from the considered variables and in different examples is robust and the results are not changed relative to the selection of the indicators and the time period.

4 Globalization and Institution: The Case of Developing Courtiers

In order to analyze the trends of globalization and institutional quality, subindexes of the Globalization Index (KOF)Footnote 6 and subindexes of the World Governance Index (WGI)Footnote 7 are used, respectively. In this chapter, data from 2001 to 2015 are used for subindexes including control of corruption, rule of law, the quality of regulation, government effectiveness, and voice and political stability. Furthermore, data of subindexes of the globalization are used such as KOF Economic Globalization Index (KOFEcGI), KOF Social Globalization Index (KOFSoGI), and KOF Political Globalization Index (KOFPoGI).

Although these data only exist for 1970 and after that, to coordinate with the data of the WGI subindex, data from the period of 2001 to 2015 are used. These data are available for the world, MENA, and other categories and each individual country. World Bank provides WGI index for countries including high income, low income, lower middle income, and upper middle income. Regarding this fact, most developing countries are not among countries with high income; therefore, in the present study, the simple average of data of low-income, lower middle-income, and upper middle-income countries are considered as a proxy of developing countries.

The globalization trends in the world, developing countries, and MENA countries are shown in Fig. 3. As it is clear from Fig. 3a, from 2001 to 2008, economic, political, and social globalization indexes in the world have been almost the same and do not seem appropriate (a figure of all three indexes is about 60); but from 2009 onward and until 2015, the situation of political globalization appeared to be better than social and economic. In developing countries, as shown in Fig. 3b, the situation is different. In these countries, the index of political globalization has risen from about 51 in 2001 to about 61 in 2015, and it has been a better situation than economic globalization and also social globalization. Indeed, in these countries social globalization has improved over time, but with the exception of 2013–2015, there has always been a worse situation than economic and political globalization.

The situation of MENA countries between developing countries is different. In these countries, the trend of political globalization has been faster than developing countries and even than that of the world, but unlike other developing countries, economic globalization has been faster than social globalization (Fig. 3c).

The comparison of three dimensions of globalization in the world, developing countries, and MENA countries is shown in Fig. 3d. This figure showed that the trend of political globalization in the MENA countries has the fastest and best conditions and the trend of social globalization, and in the next stage, globalization in the developing countries is in the worst condition.

Another important point based on Fig. 3d is that the trend of globalization is improving in all three dimensions, although economic and social globalization in developing countries is far from the other dimensions of globalization in the world.

The status of institutional quality in developing countries and the MENA countries is illustrated in Fig. 4. In developing countries, institutional quality is in an inappropriate status (Fig. 4a). In these countries, the quality of regulation, government effectiveness, and voice and political stability have the same condition and are in the worst situation. But the rule of law compared to other subindexes has a relatively better condition, and it showed the improvement of trend. Nevertheless, the quality of regulation and government effectiveness is in the worst status. Based on Fig. 4b, institutional quality in the MENA countries has an inappropriate situation compared to other developing countries, and especially the rule of law and the control of corruption—which are vital to trade—have the worst situation. The trend of the rule of law has worsened every year since 2001 and has become an inappropriate trend. In these countries, the control of corruption has the most inappropriate, and voice has the most appropriate situation.

The comparison of the situation of these indexes in MENA countries and other developing countries is presented in Fig. 4c. According to Fig. 4c, the political stability and the rule of law in the MENA countries have the worst situation, and the rule of law and the control of corruption in the developing countries are at the best situation. However, the value and trend of all indexes in these countries have an inappropriate situation.

Based on the abovementioned data, it can be concluded that the trend of economic globalization in developing countries in comparison with the world trend is inappropriate. Also, the situation of institutional quality in these countries is not desirable, so that the quality of regulation and government effectiveness have the worst situations. These factors play a vital role in the expansion of trade. Now, this question arises: What is the relationship between economic globalization and the quality of economic-legal institutions (rule of law, regulatory quality, and government effectiveness) in developing countries? Also, what is the relationship between other dimensions of globalization (political and social) and the quality of political institutions (such as political stability and voice) and the quality of social institutions (such as control of corruption) in the short run and long run?

To answer these questions, and testing the hypothesis 1–4, Granger-type causality test has been used.Footnote 8

The results presented in Table 2 reveal that there is no causal relationship between economic globalization and legal-economic institutions (rule of law and government effectiveness) in the short run (H4 is accepted) but there is at least one causal relationship in the long run (H1, H2, and H3 are accepted). This relationship with the indexes of the rule of law is bidirectional and with other indexes is unidirectional. These results are justified for developing countries by considering the inappropriate trend of the economic globalization and the inappropriate situation of government’s effectiveness.

Social globalization has a unidirectional causal relationship with the quality of social institutions (control of corruption) in both the short run and long run. As it can be seen, although the situation of social globalization in developing countries is worst, the trend continues to improve, and control of corruption in these countries is in a better situation than that of the other subindexes and the control of corruption has improved. Therefore, it can be concluded that the improvement of the social globalization in these countries will lead to improvements in the situation of social institutions. Also, there is at least one unidirectional causal relationship from political globalization to the quality of political institutions (political stability and voice) in these countries in the short and long term. These results are also justified by the situation of developing countries.

Another important point is that the quality of the various dimensions of institutions in developing countries is influenced by the corresponding dimensions of globalization and can support the globalization view of institutional quality hypothesis in these countries. Also it can be said that the increasing political stability and better rule of law can help the process of political and economic globalization in these countries in the long run.

5 Discussion

The main finding of the empirical part of the present chapter indicates that institutional quality is inappropriate and the trend of globalization, especially the economic globalization, in developing countries is not appropriate. Also, the results of the causality test revealed that different dimensions of globalization (especially in the long run) are the causes of institutional quality. Although the results of the present study should be cautious, they will be defended for various reasons. Some of these reasons include:

-

1.

In a rent-seeker-friendly economy, as rents are a dominant activity and a barrier to improving institutional quality, the economic globalization (trade openness) cannot eliminate rents. Therefore, moving toward globalization will not noticeably affect institutional improvement (Stefanadis 2010; Levchenko 2012). It’s evident that, as the institutional structure of most developing countries is rent-seeker-friendly, it is expected that in these countries, even with a move toward globalization, there will be no noteworthy improvement in institutional quality.

-

2.

The nondemocratic political system in a country and the concentration of political power in the hands of especial groups will lead to the creation and strengthening of bad institutions (Do and Levchenko 2009). In such condition, while economic globalization has both foreign competition and political power effects, the impact of political power effect dominates on the foreign competition effect, and it causes the negative impact of globalization on the institutional quality. These analyses are more consistent with the situation of developing countries.

-

3.

The existence of abundant natural resources and the phenomenon of Dutch disease, along with weak institutional quality, cause an increase in the productivity of opportunistic behaviors, and thus the economic globalization cannot improve the quality of institutions (Bergh et al. 2014). The economic structure of most developing countries, especially the MENA countries, is in such a way that there are many natural resources in these countries.

-

4.

If the circulation of information is weak and people are misinformed, inefficient institutions will be strengthened and lasting. In such a situation trade openness is unable to increase the circulation of information, and it has no positive impact on institutional quality (Bergh et al. 2014). Such a situation exists in developing countries as well.

-

5.

If the uncertainty, instability, and corruption in the society extended, people will have a shorter horizon (Bergh et al. 2014). Such situations exist in developing countries. In this condition, due to a lot of corruption and instability, there is no motivation to improve institutions in order to gain benefit from these conditions by powerful groups, and thus institutional condition cannot be noteworthily improved, even under the condition of expansion of trade.

6 Concluding Remarks

Various (Orthodox and Heterodox) theories exist to illustrate the factors affecting trade in goods and services. Fundamental emphasis of Orthodox views is based on the characteristics of trade partners. However Heterodox views have emphasized on the quality of institutions which is an important factor for the trade of various kinds of goods and services. Institutions and good institutional quality from various channels lead to a change in the volume, structure, and composition of the trade. These channels include reducing rents, reducing monopolies, reducing entry barriers, reducing friction of information, enhancing trust, the forming of relative advantage, guarantees of legal security and security of contracts, the strength of the legal system, etc. But it should be noted that the amount and direction of influence depend on the kind of institutional systems and institutional structure.

On the other hand, globalization and, in particular, the trade openness, via various channels such as changes of rents, technology transfer, foreign competition effect and political power effect, etc., affect the quality of institutions and can lead to improvement or deterioration of institutional quality. Trade openness which depends on the institutional structure of the country can have a positive or negative impact on the institutional quality of the country. If the country’s economic structure is rent-seeker-friendly (a feature of most developing countries), trade openness will destroy the institutions and institutional quality, but in producer-friendly economies (mostly in the countries of North regions), trade openness will improve institutional quality. If, after trade openness, the country is engaged in the production and the export of institutionally intensive goods and gain benefits from the related rents, there will be strong motivation for deterioration of institutional quality in these countries. The transfer of technology through trade openness in developing countries leads to increases in the political power of the middle-income group, and the motivation to create and strengthen the good or bad institutions will occur. Depending on institutional conditions in these countries, creation of bad institutions and deterioration of institutional quality will occur.

There are various studies that examine the impact of different kinds of institutions on trade of goods and services. These studies have been done by using time series data (in national and provincial levels), panel data, and different types of goods and institutions. The common finding of most studies related to the impact of legal-economic institutions (mainly contract institutions and property rights institutions) is that the improvement of the situation of these institutions leads to the expansion of the production and trade of goods and services. Furthermore, in various empirical studies, the impact of economic globalization on the quality of institutions has been investigated with the panel data, but the same result has not been achieved. The type and direction of this effect vary depending on the level of economic development of the countries, the amount of available natural resources, the type of indexes used, and so on. The common theme of most studies is that initially the direction of causality (from the economic globalization to the institutional quality or vice versa) is assumed, and then, the effect of these variables has been theoretically or empirically investigated. In a few studies such as in Nicolini and Paccagnini (2011), the investigation of the direction of causality between trade openness and institutions is taken into consideration.

In addition, there are fewer studies that specifically focused on the developing countries. Accordingly, the purpose of this chapter was to fill such a research gap. The findings point to the inappropriate situation of economic globalization and institutional quality, in particular the quality of regulation and government effectiveness in developing countries. Also the control of corruption has no appropriate situation in these countries. Accordingly, there is no causal relationship between these two variables in developing countries in the short run.

The overall finding of the present study shows that mostly there is at least one unidirectional causal relationship between various dimensions of globalization and different types of institutions—from globalization to institutions in developing countries. Therefore, in general we can support the globalization view of institutional change cautiously. Therefore, it is suggested that policy-makers in developing countries gain benefit from the advantages of globalization, try to improve the institutional quality of their countries (to a certain threshold), and effort to create and strengthen good institutions.

Empirical analysis in this chapter has been done with some limitations. (1) The time period which is considered in the present study was short because of a lack of data related to the WGI subindexes. (2) Several proxy variables for globalization and institutional quality are used, while there are various indexes. Accordingly, the findings of the present study should be considered with precaution. Regarding this fact that a unique interpretation cannot present for all countries, it is suggested that, in future studies, the causal relationship between the proxies for globalization and institutional quality at the national level with more data and various indexes should be investigated. By accessing more data, other econometric methods can be used.

Notes

- 1.

These findings are presented in Sect. 4 of this chapter in detail.

- 2.

- 3.

The contract institutions seek to support private contracts, but property rights institutions are seeking to limit expropriation of private property by the government and political elites (Bhattacharyya 2012: 257).

- 4.

This naming is from the author.

- 5.

- 6.

It should be noted that financial openness and FDI have impact on domestic institutions via various channels, especially in developing countries, that are not discussed in this chapter. For further study, refer to the study of Kant (2016).

- 7.

- 8.

- 9.

Three-step methodology has been used in this chapter. In the first step, a Pesaran (2007) cross-sectional dependency test is used to determine the cross-sectional dependency or independency. In the second step, based on the results of these tests, we use Pesaran’s CIPS unit root test. In the third step, we used the panel vector error correction model (PVECM) as Eqs. (1) and (2):

\( \Delta {\mathrm{Glob}}_{it}={\sum}_{j=1}^n{b}_{1j}\Delta {\mathrm{Glob}}_{i,t-j}+{\sum}_{j=1}^n{c}_{1j}\Delta {\mathrm{Insti}}_{i,t-j}+{d}_1{\mathrm{ECT}}_{i,t-1}+\Delta {\varepsilon}_{1 it} \) (1)

\( \Delta {\mathrm{Insti}}_{it}={\sum}_{j=1}^n{b}_{2j}\Delta {\mathrm{Glob}}_{i,t-j}+{\sum}_{j=1}^n{c}_{2j}\Delta {\mathrm{Insti}}_{i,t-j}+{d}_2{\mathrm{ECT}}_{i,t-1}\Delta {\varepsilon}_{2 it} \) (2)

where Δ indicates the first-order difference of the variables and ECTi, t − 1 is the error correction term with lag (1). Glob stands for subindexes of the Globalization Index (KOF), and Insti stands for subindexes of the World Governance Index. Also n and m are optimal lag length which are determined by some information criteria. According to the estimation of Eqs. (1) and (2) and by the joint significance test, the coefficients of the endogenous variables and the coefficient of ECT can perform the short-term and long-term Granger-type causality test. If the coefficient of ECT in Eq. 1 (2) is statistically significant, it can be said that the institution’s quality (globalization) causes globalization (institutional quality) in the long run. If two variables are significant (d1 = d2 ≠ 0), thus there is a bidirectional causality between two variables. But for diagnosing the existence or lack of causality in the short term between these variables, the hypotheses test of 3 and 4 should be done:

H0 : c11 = c12 = … = c1n = 0 (3)

H0 : b21 = b22 = … = b2n = 0 (4)

The alternative hypothesis in these cases is that at least one of c1j or b2j is different from zero. If the null hypothesis of the 3 (4) is rejected, then institutional quality (globalization) causes globalization (institutional quality). Otherwise, if the hypotheses 3 and 4 are rejected simultaneously, the direction of causality will be bidirectional.

References

Acemoglu D, Johnson S (2005) Unbundling institutions. J Polit Econ 113(5):949–995

Acemoglu D, Johnson S, Robinson J (2005) The rise of Europe: Atlantic trade, institutional change and economic growth. Am Econ Rev 95(3):546–579

Acemoglu D, Johnson S, Robinson J, Thaicharoen Y (2003) Institutional causes, macroeconomic symptoms: volatility, crises and growth. J Monet Econ 50:49–123

Acemoglu D, Robinson J (2006) Economic origins of dictatorship and democracy. Cambridge University Press, New York

Al-Marhubi FA (2005) Openness and governance: evidence across countries. Oxf Dev Stud 33:453–471

Álvarez IC, Barbero J, Rodríguez-Pose A, Zofío JL (2018) Does institutional quality matter for trade? Institutional conditions in a sectoral trade framework. World Dev 103:72–87

Araujo L, Mion G, Ornelas E (2016) Institutions and export dynamics. J Int Econ 98:2–20

Asongu SA, Biekpe N (2017) Globalization and terror in Africa. Int Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inteco.2017.12.005

Aziz N, Hossain B, Mowlah I (2018) Does the quality of political institutions affect intra-industry trade within trade blocs? The ASEAN perspective. Appl Econ. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2018.1430336

Baccini L (2014) Cheap talk: transaction costs, quality of institutions, and trade agreements. Eur J Int Relat 20(1):80–117

Bergh A, Mirkina I, Nilsson T (2014) Globalization and institutional quality: a panel data analysis. Oxf Dev Stud 42(3):365–394

Bhattacharyya S (2012) Trade liberalization and institutional development. J Policy Model 34:253–269

Bonaglia F, de Macedo JB, Bussolo M (2001) How globalization improves governance. OECD Working Papers, 181

Czinkota MR, Skuba CJ (2014) Contextual analysis of legal systems and their impact on trade and foreign direct investment. J Bus Res 67:2207–2211

De Groot HLF, Linders G-J, Rietveld P, Subramanian U (2004) The institutional determinants of bilateral trade patterns. KYKLOS 57(Fasc. 1):103–124

Depken CA II, Sonora RJ (2005) Asymmetric effects of economic freedom on international trade flows. Int J Bus Econ 4(2):141–155

Desroches B, Francis M (2006) Institutional quality, trade, and the changing distribution of world income. Bank of Canada Working Paper 2006-19

Djankov S, LaPorta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F, Shleifer A (2002) The regulation of entry. Q J Econ 117(1):1–37

Do QT, Levchenko AA (2009) Trade, inequality, and the political economy of institutions. J Econ Theory 144:1489–1520

Fainshmidt S, Judgeb WQ, Aguilerac RW, Smith A (2018) A varieties of institutional systems: a contextual taxonomy of understudied countries. J World Bus 53:307–322

Feenstra RC, Hong C, Mad H, Spencer BJ (2013) Contractual versus non-contractual trade: the role of institutions in China. J Econ Behav Organ 94:281–294

Francois J, Manchin M (2013) Institutions, infrastructure, and trade. World Dev 46:165–175

Gani A, Clemes MD (2013) Modeling the effect of the domestic business environment on services trade. Econ Model 35:297–304

Gani A, Clemes MD (2016) Does the strength of the legal systems matter for trade in insurance and financial services? Res Int Bus Financ 36:511–519

Gwartney J, Lawson R (2005) Economic freedom of the world 2005 annual report. The Fraser Institute

International Monetary Fund (2005) World economic outlook: building institutions. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC

Kant C (2016) Are institutions in developing countries malleable? J Policy Model 38:272–289

Kant C (2018) Financial openness & institutions in developing countries. Res Int Bus Financ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2018.03.001

Levchenko AA (2004) Institutional quality and international trade. IMF Working Paper WP/04/231

Levchenko AA (2007) Institutional quality and international trade. Rev Econ Stud 74(3):791–819

Levchenko AA (2008) International trade and institutional change. University of Michigan, Mimeo

Levchenko AA (2011) International trade and institutional change. NBER Working Paper No 17675

Levchenko AA (2012) International trade and institutional change. J Law Econ Organ 29(5):1145–1181

Long C, Yang J, Zhang J (2015) Institutional impact of foreign direct investment in China. World Dev 66:31–48

Manolopoulos D, Erifili C, Constantina K (2018) Resources, home institutional context and SMEs’ exporting: direct relationships and contingency effects. Int Bus Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2018.02.011

Moenius J, Berkowitz D (2011) Law, trade, and development. J Dev Econ 96:451–460

Mossalanejad A (2014) Institutionalism and globalization. University of Tehran Press [in Persian]

Muye IM, Muye IY (2017) Testing for causality among globalization, institution and financial development: further evidence from three economic blocs. Bursa Istanbul Rev 17(2):117–132

Nicolini M, Paccagnini A (2011) Does trade foster institutions? Rev Econ Inst, 2

North D (1981) Structure and change in economic history. W.W. Norton, New York

Nunn N (2007) Relationship-specificity, incomplete contracts, and the pattern of trade. Q J Econ 122(2):569–600

Nunn N, Trefler D (2014) Domestic institutions as a source of comparative advantage. In: Gopinath G, Helpman E, Rogoff K (eds) Handbook of international economics, vol 4. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 263–315

Palangkaraya A, Jensenb PH, Webster E (2017) The effect of patents on trade. J Int Econ 105:1–9

Pesaran MH (2007) A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross section dependence. J Appl Econ 22:265–312

Potrafke N (2013) Globalization and labor market institutions: international empirical evidence. J Comp Econ 41:829–842

Ranjan P, Lee JY (2007) Contract enforcement and international trade. Econ Polit 19(2):191–218

Renani M, Moayedfar R (2012) The decline cycles of morals and economy: the social capital and development in Iran. Tarh-E-No Press, Tehran

Samadi AH (2008) Property rights and economic growth: an endogenous growth model. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Isfahan University, Iran

Samadi AH (2018) Institutions and entrepreneurship in MENA countries. In: Faghih N, Zali MR (eds) Entrepreneurship ecosystem in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), contributions to management science. Springer International Publishing AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75913-5_3

Samadi AH, Amareh J (2010) Economic crimes, income inequality and economic development: the case of Iran (1983-2006). Journal of Economic Essays 7(14). Autumn & Winter 2010

Stefanadis C (2010) Appropriation, property rights institutions, and international trade. Am Econ J Econ Pol 2(4):148–172

Stieglitz JE (2002) Globalization and its discontents. W.W. Norton

Tang H (2012) Labor market institutions, firm-specific skills, and trade patterns. J Int Econ 87:337–351

Tavares SC (2007) Do rapid political and trade liberalizations increase corruption? Eur J Polit Econ 23(4):1053–1076

Wei SJ (2000) Natural openness and good government. NBER Working Paper 7765

Young AT, Sheehan KM (2014) Foreign aid, institutional quality, and growth. Eur J Polit Econ 36:195–208

Yu M (2010) Trade, democracy, and the gravity equation. J Dev Econ 91:289–300

Yu S, Beugelsdijk S, de Haan J (2015) Trade, trust and the rule of law. Eur J Polit Econ 37:102–115

Acknowledgment

I would like to express my sincere appreciation to Prof. Dr. Nezameddin Faghih for providing the opportunity to contribute the compilation of one chapter of this book and accepting my proposal for the compilation of this chapter. I am also thankful to the Springer Publishing Company by providing the right conditions for the publication of the book. I also would like to appreciate two honored anonymous reviewers of this chapter for their meticulous reviews, valuable comments, and useful suggestion to improve this study. Explicitly, I’m responsible for possible mistakes in the present chapter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Samadi, A.H. (2019). Institutional Quality and Globalization in Developing Countries. In: Faghih, N. (eds) Globalization and Development. Contributions to Economics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14370-1_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14370-1_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-14369-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-14370-1

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)