Abstract

In response to pressure from Māori iwis (tribes), the New Zealand Government announced in 2017 that the Whanganui River had been granted the legal status of a living entity. This alternate cultural view has energised a lively international debate about of what constitutes ‘living kinds’ and ‘personhood’. This chapter asks whether non-human species, rivers and whole ecosystems should be considered in these terms. And, if so, should they have concomitant legal rights?

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

After nearly 150 years of debate with Māori iwis (tribes), and recent intense efforts to bring complex changes through the legal system, the New Zealand Government announced in 2017 that the Whanganui River had been granted the status of a living entity. This defined ‘the River from the mountains to the sea, its tributaries, and all its physical and metaphysical elements, as an indivisible and living whole’ (New Zealand Government 2017: 129). In accord with the bi-culturalism through which New Zealand/Aotearoa strives to acknowledge the cultural beliefs and values of its indigenous people, the decision was largely a response to the tikanga (customs and beliefs) of the Māori people located along and around the river. For them, the river is a living ancestor (Te Awa Tupua): an entity indivisible from themselves, and whose well-being is interdependent with their own (Muru-Lanning 2010) (Fig. 8.1).

Although it is more common to draw a distinction between a ‘living entity’, which may or may not be a person, and ‘personhood’, which is generally assumed to entail a specific social identity, in this instance, these definitions were conflated. From now on, the new law stated, the river would have rights similar to those granted to corporate ‘persons’ such as trusts, companies and societies (Stone 1972). ‘Te Awa Tupua is a legal person and has all the rights, powers, duties, and liabilities of a legal person’ (Ibid: 14(1)). Nominated individuals—a representative for the Crown and one from the Whanganui iwi [tribes]—would have a responsibility to ‘speak for’ the river and promote its rights and interests, not just in terms of its management and use, but also within the legal system. A new role, To Pou Tupua was created by the Bill ‘to be the human face of Te Awa Tupua and act in the name of Te Awa Tupua’ (Ibid: 18(2)). Reflecting the relationship between the Māori iwis and the River, the Bill lists various functions for this office, including:

-

to act and speak for and on behalf of Te Awa Tupua;

-

to promote and protect the health and well-being of Te Awa Tupua;

-

to perform landowner functions with respect to land vested in Te Awa Tupua under the legislation;

-

to maintain the Te Awa Tupua register, which is a register of hearing commissioners qualified to hear and determine applications under the Resource Management Act 1991 for resource consents (a) relating to the Whanganui River: (b) for activities in the Whanganui River catchment that affect the Whanganui River (Ibid. 57. See also New Zealand Government 1991) and

-

to administer a contestable trust fund established to ‘support the health and well-being of Te Awa Tupua (Ibid: 57).

The legal decision provided a settlement of $80m (NZD) in legal redress, and a further $1m to establish a legal framework for the protection of the river, which will also serve, potentially, as a model for similar protective measures elsewhere (Ruru 2013).

The Minister responsible for the Treaty of Waitangi negotiations, Chris Finlayson, noted that the decision brought the longest-running litigation in the country’s history to an end:

Te Awa Tupua will have its own legal identity with all the corresponding rights, duties and liabilities of a legal person… The approach of granting legal personality to a river is unique… it responds to the view of the iwi of the Whanganui river which has long recognised Te Awa Tupua through its traditions, customs and practice. (Roy 2017)

The lead negotiator for the Whanganui iwi, Gerrard Albert expressed a hope that the decision would set a precedent. He observed that the decision reflected a basic premise of a Māori worldview in which people considered themselves to be at one with, and having equal status to, the mountains, the rivers and the seas, thus encapsulating the core principles of ecological justice:

We have fought to find an approximation in law so that all others can understand that from our perspective treating the river as a living entity is the correct way to approach it, as an indivisible whole, instead of the traditional model for the last 100 years of treating it from a perspective of ownership and management. (Roy 2017)

Responses, both within New Zealand/Aotearoa and internationally, represented a spectrum of views. There were those who found it ‘inspirational’ that such respect and acknowledgement of intrinsic value could be accorded to a river. Comments on newspaper websites (Roy 2017) (anonymised here) included:

The most uplifting development in how we regard our planet that I think I’ve ever read about. Pure joy.

Lovely news - I love it when the law is used to stand up for the environment.

This story really made me smile. I’m so glad that there are people fiercely defending the planet we’re so keen on destroying.

Bang on! Very proud to be a New Zealander and to see the legitimate interests, and grievances, of Māori recognised and dealt with such innovative measures… People inevitably ‘joke’ about the river being like a person but this is a very significant and historic event.

What a glorious precedent - recognition that a complex ecosystem really is a living entity.

However, there were also many negative comments on public websites (and quite a few more ‘removed by the moderator’). In New Zealand, although some respondents were sympathetic to the history of colonial dispossession and disadvantage that had to be navigated, and to the idea that there was case for redress both for the Māori communities and the river, there was some cynicism about the financial settlement. But the majority of negative comments were those that rejected the notion that a river could be a person, or equal to a person. Reflecting a common tendency to conflate ethical and religious ideas, these often expressed unease with what they saw as the introduction of ‘religious’ ideas into a purportedly secular legal system.

You got environmental laws for this. What’s next - equating a rock to a human?

I can see how rights will work but how is the river going to meet its ‘duties and liabilities as a legal person’? If it floods and damages something will it/the tribe pay compensation?

It has no characteristics of a living entity. Idiocy. It has no sentient capabilities… More religious twaddle made into law. Protect the river, but do it through environmental laws.

Oh dear. I’m all in favour of keeping rivers clean but modern secular states shouldn’t make decisions on the basis of religious beliefs.

For the most part, the international coverage provided little or no insight into Māori lifeways, or considered that there might be diverse viewpoints within these. Many commentators nevertheless accepted that the decision was based on accommodating a (rather monolithic) view of indigenous ways of thinking, and welcomed this as a general critique of dominant practices:

This is the best, most sane item of news I’ve read for a long long time. The Maoris believe things we all need to believe in order to live honestly in our environment. Thank you New Zealand and the tribe of Whanganui for your flexible thinking and persistence - respectively.

Respondents expressed relatively little anxiety about acknowledging the river as a living entity. However, without the benefit of details about the cultural context, there was some bafflement as to why this categorisation should apply specifically to a river:

If a river is a living entity, then so is the rest of the universe … there are all manner of uncontroversial living entities (for example, dragonflies and crocodiles) that would also need to be granted the same legal status as a human being.

If a river can be given human rights, then why not a meadow?

Some people got the point that the objective was to define more egalitarian relationships with the non-human world:

At last, somewhere, humanity is waking up to the truth. We share this planet equally with all beings and nature’s creation.

Like many people here, I was hugely heartened to see this item… We need a better, more accurate way of seeing ourselves, i.e. as an integral part of Nature in which ‘we live, move and have our being’.

However, for many commentators, such as the one quoted below, this did not translate into a concept of personhood or legal rights:

I have tried in vain to find in the article the argument from moving from the river’s status as a living entity to granting it the same legal status as a human being.

Protection in Law

The establishment of the Whanganui River as a legal ‘person’ therefore brought to the fore some pressing questions about how societies define living kinds and personhood; whether non-human species, rivers, or even whole ecosystems should be considered in these terms; and whether they should have legal rights and protection similar or equal to those accorded to human beings. The case also highlighted some more subtle issues about who decides these matters and how, and the extent to which minority views might influence such debates (see Chap. 11, Gray and Curry on ecodemocracy, this volume).

Indigenous communities have long provided inspiration to conservationists’ efforts to promote the interests of non-human beings and ‘nature’ more generally. Though their relations with ‘nature’ have sometimes been romanticised, respect for non-human well-being is often integral to indigenous beliefs and values, and embedded in their traditional forms of law (Bicker et al. 2004). For example, in Aboriginal Australia, Ancestral Law, transmitted from one generation to the next via stories, images, and performance, often contains homilies about not overusing resources. Kunjen elders in Cape York therefore note instructions about being required to replace the main root in harvesting yams; maintaining sufficient ‘spear tree’ to allow regrowth; and respecting restrictions on hunting and gathering at sacred sites which, it has been posited, therefore act as generative ‘game reserves’ (Strang 1997; see also Dudley et al. 2009). The long-term persistence of Aboriginal lifeways over millennia suggests that the integration of these values with low resource use and population control (which Kunjen elders recall as a normal practice prior to colonial settlement) has enabled high levels of social and ecological sustainability.

Attempts to enshrine protection for non-human beings also have a long history in legal systems based on Roman Law. For example, one of the first (written) laws to provide such protection was initiated by St. Cuthbert on Lindisfarne Island in the sixth century, to protect his beloved Eider Ducks, still known locally as ‘Cuddy Ducks’ because of his efforts. However, despite a plethora of such legislation, particularly in the last century, industrialised societies have adopted wholly unsustainable growth-based economic practices and levels of population expansion. The result is a major failure to protect the needs and interests of non-human beings and ecosystems sufficiently to prevent a massive global reduction in biodiversity and a rate of species loss equivalent to previous mass extinction events (IUCN 2018).

Recognition of this failure has driven a campaign to reframe the debate in terms of legal rights for non-human beings, aiming for some degree of equivalence to human rights, for example those set out in the Declaration of Human Rights established by the United Nations’ General Assembly in 1948. These included a right to life, the prohibition of slavery, a right to basic dignity, adequate standards of living, and a range of freedoms (for example in thought, movement, beliefs, and associations).

Such endeavours build on earlier concerns about animal experimentation. The 1990s saw a campaign to extend legal rights and protection to ‘higher’ primates, in particular chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans and bonobos. The Great Apes Project, established in 1993 by the philosophers Peter Singer and Paola Cavalieri, argued that ‘non-human hominids’ should enjoy the right to life, freedom and not to be tortured, and should be regarded as sentient ‘persons’. These rights were approved by the Spanish Government, and, as Pedro Pozas, the Spanish director of the Great Apes Project, put it: ‘This is a historic day in the struggle for animal rights and in defense of our evolutionary comrades which will doubtless go down in the history of humanity’ (Glendinning 2008). Not long afterwards, the British Government passed laws preventing experimentation on chimpanzees, orangutans and gorillas, and in 1999 the New Zealand Government did likewise.

However, Perlo identifies a problem with ‘moral schizophrenia’ in which, on the one hand, many societies do want to accept that non-human beings should have rights and interests, but at the same time remain unwilling to undertake the changes in behaviour towards them that would reflect any equality in this regard (2009: 4). There is a persistent problem that ‘when push comes to shove’, good intentions quickly give way to pressing human interests. Thus in the Great Apes campaign, Colin Blakemore (Head of the UK’s Medical Research Council 2003–2007), pointed out that, while he was pleased that the great apes were not being used for experiments, a pandemic affecting only human and non-human apes might re-open the case for such research (Glendinning 2008).

This suggests that while the campaign to assert legal rights for non-human beings and ‘living entities’ is a useful pull towards more reciprocal human-non-human relations, as long as ‘push comes to shove’ for humankind, as it does most of the time, achieving significant ecological justice is likely to remain challenging.

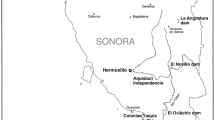

Recently, there have been increasing efforts to establish legal rights for nature more broadly (Berry 2002; Cullinan 2003; Washington 2013). In response to pressure from its indigenous communities, the Government of Ecuador passed legislation in 2008 securing the ‘rights of nature’, Pachamama, in its Constitution. Bolivia followed suit a few years later with a ‘Law for Mother Earth’. As illustrated by the Standing Rock debate, indigenous communities in America have continued to try to apply similarly protective laws based on their own cultural beliefs and values. Their voice is also evident in some State-based campaigns for ecological justice, for example in Washington State (see Washington State Department of Health 2017; Washington Environment Council 2018). At an international level, activists have been campaigning for a UN Declaration specifically protecting the Rights of Nature (Gray and Curry 2016; Schläppy and Grey 2017; see also Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature 2018).

New Zealand/Aotearoa itself has gone down this road previously. In a 2014 Waitangi Treaty settlement with the Ngäi Tuhoe iwi, their forest homeland, Te Urewera, was provided with its own legal identity and, as with the Whanganui River, an arrangement was made through which iwi and Crown nominees would act in its best interests (New Zealand Government 2014). There have been attempts to confer similar rights on rivers in various parts of the world, with some success in relation to the Ganges and Yamuna Rivers in India, and the Atrato River in Colombia. A campaign to establish further such rights has been promoted by the Earth Law Centre (ELC). Based in New York and San Francisco, but linked to multiple NGOs internationally, the ELC aspires to be ‘a global force of advocates for the rights of nature’:

Just as people have fundamental rights, so too should nature. EARTH LAW is the idea that ecosystems have the right to exist, thrive, and evolve – and that nature should be able to defend its rights in court. EARTH LAW looks at the pressures on the Earth that contribute to the destruction of its ecosystems and species. It then argues that a balanced approach can provide for the entire Earth community, including humans. We envision a future in which humans and nature flourish together. (Earth law Centre website 2018)

The ELC has devised a Universal Declaration of rights for rivers:

The Earth Law Center is committed to achieving legal personhood for more rivers and waterways. In support of a campaign to establish rights for the Rio Magdalena and other rivers, ELC has developed a draft Universal Declaration of River Rights. The Declaration draws from victories for the rights of rivers worldwide as well as scientific understandings of healthy river systems. (Ibid)

Deepening anxieties about climate change and the destruction of ecosystems have sharpened debates about how to avert catastrophic levels of extinction, environmental degradation, major shortfalls in freshwater supplies and threats to food security. In the last few years there has been somewhat of a confluence of ideas between activist counter-movements and parts of the academy. Philosophical and anthropological ideas about non-human and material worlds have found increasing common ground with the worldviews of indigenous communities and the aims of conservationists (Brightman and Lewis 2017; Chen et al. 2013). Although not going so far as to define rights for non-human beings, a recent initiative by the United Nations to develop some new Principles for Water, has foregrounded the intrinsic value of water (United Nations 2018; Strang 2017). While societies continue to struggle to institute real changes, there is growing recognition that a new intellectual paradigm—a repositioning of humankind in relation to non-human kinds—is needed to move towards more sustainable practices.

However, instituting such fundamental changes—if achievable at all—is a long-term endeavour. Given the lack of impact of previous legislative efforts, and the continuing rise in extinctions, many international activists feel that providing non-human species, rivers and ecosystems with legal rights akin to those accorded to humans is key to ensuring that greater parity and immediacy is given to non-human needs and interests. The comments responding to the announcement regarding the Whanganui River indicate that gaining widespread understanding and support for such rights is challenging. This is something that might benefit from anthropology’s capacities for cross-cultural translation, and its abilities to elucidate diverse worldviews.

Rivers as Living Kinds

There are several areas of anthropological thinking that illuminate how a river might be considered as a living entity. The first is classic ethnographic research examining how societies think about whether or not things are ‘alive’. Atran (1990) observed that, cross-culturally, there is a general expectation of animation—i.e. that things that are alive will move, an idea that is nicely encapsulated in the Biblical phrase defining the difference between: ‘the quick and the dead’ (King James Bible 1611). However, what is considered to be animate, and the extent to which this overlaps with concepts of animism (which is not the same thing by any means) varies considerably across cultures. For many indigenous communities, things such as rocks, trees, water bodies and entire landscapes may be animated by ancestral or spiritual forces which, in local cosmological terms, renders them ‘alive’ and sentient (Fig. 8.2).

Aboriginal Australian cultural landscapes provide a useful example. Living as hunter-gatherers for millennia prior to European colonisation, many indigenous communities have maintained permanent relations with the clan ‘country’ from which, according to their beliefs, they are spiritually generated and to which, at the end of their lives, their spirit must return. This is a sentient landscape, inhabited by the totemic ancestral beings who created the world and its human and non-human inhabitants during the ‘early days’ of cosmogenesis, commonly called the Dreamtime or Story Time. The ancestral beings remain, held in the land and its waters, as a source of the Ancestral Law that underpins every aspect of Aboriginal life, and as a continued presence that renders the landscape sentient, alive and responsive to human action. Thus ancestral beings inhabiting trees that manifest their presence may ‘become’ new ones when their current ‘home’ dies. Objects may become visible, or disappear. Even rocks might be said to ‘move around’. In explaining these powers, Kunjen elders provide their own translation of ideas, drawing an analogy between ancestral forces and electric batteries, whose charge enables action or animation (Strang 1997).

Similar ideas underpin Māori cultural beliefs in which ancestral beings created the world, also taking non-human form as manifestations of seas, forests, rivers and so forth. Their continued presences composes a sentient, responsive environment which, as Gerrard Albert observed (in 2017), is ‘not divisible’ from its human inhabitants.

For both Māori and for Aboriginal Australians, then, the non-human world and its material components contain the consciousness and agency of their ancestral beings. In both cases, water itself has a central role, in that it is the substance that carries ‘living being’ over time. In Australia, this understanding is expressed through the Rainbow Serpent, from which all other beings emerged in the Dreamtime, and which continues to generate all forms of life. In New Zealand/Aotearoa, while water guardian beings such as taniwha serve to articulate Māori ideas about the sentience and responsiveness of non-human worlds, rivers are primarily understood more holistically, as the ‘living entities’ from which life emerges over time. They are thus readily described as the ‘living ancestors’ of the human communities conjoined with them ‘from the mountains to the sea’ (New Zealand Government 2017: 129(1)).

For industrialised societies, ideas about ‘aliveness’ come primarily from science, in which the category of living kinds is generally confined to biological organisms in which there are discernible material processes in motion, such as transpiration and growth in plants, and respiration, circulation etc. in animals. Scientific categories underpin popular understandings that plants are ‘alive’, but lacking in sentience, and that non-human animal species inhabit some kind of spectrum of sentience or consciousness, with those inhabiting the ‘upper’ echelons (i.e. those most like humans) assumed to have more intrinsic value in consequence (Singer 1975). The potential to consider a river as a ‘living entity’ is similarly hampered by a Cartesian view of a material world composed of physical properties and behaviours rather than sentient forces (Oelschlaeger 1991). The ‘disenchantment’ of science reduces water to H2O: a cleaning and irrigating fluid, composed of atoms rather than ancestors (Illich 1986; see also Linton 2010).

However, Western societies contain both historical and recent ideas about water that, if brought to the fore, provide some basis for thinking more imaginatively. For those assuming that there is a spiritual dimension of being, there are deep temporal aquifers of beliefs about ‘living water’ to which Celtic and, Roman societies subscribed, believing its agency to be manifested in aquatic deities; in wells with generative and healing forces; or in ‘holy water’ imbued with spiritual power (Bord and Bord 1985; Taylor 2010). The extraordinary persistence of such ideas over time is demonstrated in contemporary pagan and New Age beliefs in water’s spiritual or healing powers, and in contemporary Christianity, which—having adopted such ideas foundationally—continues to represent water as the substance of the spirit (Tvedt and Oestigaard 2010; Lykke-Syse and Oestigaard 2010).

Those committed to secular ways of thinking are by no means bereft of such ideas. A universal understanding that water is essential to the functionality of all biological organisms also imbues it with a core meaning as the essence of life. In this sense, water ‘animates’ all living kinds, providing a secular vision of ‘quickness’ that requires no religious underpinnings. It also provides an important image of interconnectedness that, both materially and imaginatively, locates humankind within the larger non-human world. Such thinking has been articulated via visions of the ‘biosphere’, first proposed by Vernadsky in the early 1920s (1986), and further developed by Lovelock in his ‘Gaia’ theory (1987[1979]). Also useful in this regard is the McMenamin and McMenamim (1994) connective notion of the ‘Hypersea,’ in which they observe that all biological organisms began in a deep aquatic past, so that even after making it onto terra firma, they nevertheless retained their total reliance upon a shared irrigating flow—a Hypersea—of water.

Recent anthropological writing on materialism has widened understandings about the dynamic interactions between all material and living kinds (Coole and Frost 2010). Latour (2005) has provided a vision of interacting ‘assemblages’ of people, non-human beings and things; Tsing has observed the active ‘friction’ between the material and organic participants in systems (2004); and Bennett (2009) has considered the liveliness of matter. This work foregrounds the ‘quickness’ of the material world and its active agency in events. Thus Edgeworth highlights the power of rivers in acting upon the landscape, and upon ourselves (2011); Krause looks at how the movements of rivers encapsulate notions of liveliness (2016); and De la Croix highlights the way that water enables concepts of flow (2014). As I have noted in my own work, water also contains its own ‘liveliness’. Its material properties—fluidity, reflectivity etc.—mean that it is constantly animated or in motion, and is therefore readily perceived as being alive.

Although the new materialism cited above has sometimes been criticised for downplaying human responsibilities for a destructive Anthropocene, a dynamic view of the world as a flux of lively, interactive processes does make it more feasible to locate all living kinds, including ourselves, within it. Such an inclusive repositioning of humankind is further aided by increasing understandings about non-human living kinds, their cognitive and sensory capacities, and their own ways of engaging with and perceiving environments. Building on earlier work about human-animal relations (Serpell 1996; Haraway 2008), recent interspecies ethnographies have both illuminated non-human experiences and highlighted the multiple relationalities between living kinds (Kirksey and Helmreich 2010). Such insights into non-human worlds can also serve to strengthen appreciation of their complexities, to evoke wonder, and to heighten concern for their well-being.

Placed within these ways of thinking, the notion of a river as a ‘living entity’ is not difficult to comprehend, and it is not a much larger stretch to appreciate its generative capacities as a ‘living ancestor’. Nor is it hard to see the flow of water that a river represents as part of a wider flow of life processes that are indeed visible as well in a meadow, a forest, or in entire ecosystems. If humans lived for long enough, we would also be able to discern much slower material processes of erosion, entropy etc. As Heraclitus put it, anticipating physicists in their development of rheology, ‘everything flows’ (πάντα ῥεῖ) (Cratylus n.d.). It is merely a matter of time (Strang 2015). But this reality also highlights the brief temporality of ‘persons’ which helps to explain why it may be difficult to extend this notion to entities with less visible lifespans.

Rivers as Persons

Anthropological research has articulated considerable cultural diversity in notions of what constitutes a person. Material culture specialists have explored the ways in which personhood is embedded in objects (Csikzentmihalyi and Rochberg-Halton 1981), and as noted above, work on human-animal relations has shown how non-human beings can be quite readily accepted as kin or semi-persons. Also useful is the literature on how wider extensions of social identity and personhood might be considered as manifestations of ‘extended mind’ (Clark and Chalmers 1998). However, there remains a considerable gap between abstract projections of personhood into things, environments and non-human beings, and a more specific acceptance of non-human beings and things as persons with concomitant legal rights (Kopnina 2017).

While acknowledging rivers as living entities may provide a partial bridge towards this idea, the notion of a river as a person is challenging. Personhood is more generally defined in conjunction with social identity and reflexive consciousness. The notion of ‘higher primates’ being included as ‘evolutionary comrades’ (as defined by the Great Apes project) is therefore not impossible to countenance. Many people consider their domestic pets as persons and even kin (and indeed might treat them better than their human relatives), but they still draw a distinction between human and non-human persons. There is a much larger gap between companion animals and the domesticated species categorised as ‘food’ and, as noted above, with the Cartesian ‘disenchantment’ of the material world, an even sharper distinction between persons and non-sentient things, including rivers.

For European societies there are further impediments to seeing non-humans as persons. Industrialised economic practices, dependent upon consumerism, are intrinsically exploitative of non-human worlds, and are supported by secular neoliberalism. A heavy influence is maintained by Christian religious beliefs historically containing a deep concern to separate humankind from ‘the beasts of the field’, and to assume the moral superiority of human (or at least male human) beings. Evolutionary thinking, while promoting a sense of shared origins, has also encouraged a vision of progressive development and hierarchy in which human-non-human relations are intrinsically unequal. Such influences have contributed to notions of ‘dominion’, and dislocated humanity from a shared sphere of living kinds.

They have also entrenched, over centuries, a dualistic worldview in which (feminised) Nature is ‘other’ to (masculinised) human Culture, creating a sharp divergence of ideas between societies in which these ideas became dominant, and those for whom such dualism is not meaningful, and who locate their social identity within an undifferentiated human and non-human world (Plumwood 1993). In writing about indigenous Australians, I have described this contrast as a concept of Nature as ‘Self’ and ‘Other’ (Strang 2005; see also Kopnina 2016; Rolston 2001). Ingold (2000) proposed a similar division between those dwelling ‘in’ and ‘on’ the earth, commenting that ‘the world can only exist as nature for a being who does not belong there’ (P. 20). It has been argued that culture may be seen as a (distinctive) part of nature (Gare 1995; Plumwood 2002), which quite reasonably implies that culture is simply a thing that humans do. Anthropological work on cultural landscapes (Bender 1993) has made it clear that these emerge from both human and non-human agencies. However, common definitions of culture as a product of specifically human activities, and persistent ideas about nature as ‘other’, present some risk that defining the ‘rights of nature’, while potentially upholding non-human rights, may also reaffirm a flawed perceptual dualism between Nature and Culture.

Identification with the non-human is clearly important in defining the extent to which it is seen as something that must be protected (Naess 1985; see also Milton 2002). How does such co-identification come about? Close affective attachment to places and their non-human inhabitants often goes hand in hand with belief systems that include non-human (totemic) ancestral beings (Morris 2000). This enables a powerful co-identification that embraces the non-human as ‘self’ rather than ‘other’. Returning to our ethnographic examples above, in Cape York, clans are typically ‘descended from’ ancestral beings in the form of animals, birds, and elements of the material world, such as clouds or floodwaters. And, because water embodies the Rainbow Serpent itself, which is the source of all ancestral beings, rivers and water sources are particularly imbued with a powerful ancestral presence (Strang 1997, 2009).

Māori creation stories similarly involve non-human deities such as Tane, the God of the Forest, and describe both human and non-human ancestral beings, with multiple stories about ancestral taniwha (water beings). Older renditions of such stories are quite literal:

Of all the descendants of Rua-pani, the Ngati-Hine-hika and Ngati-Pohatu, of Te Reinga, are perhaps the most interesting… Their ancestor Tane-kino… is said to have intermarried with a race of Taniwha, who were the original inhabitants of the Whakapunake mountain and Te Reinga falls… From the tale told by Ngati-Hine-hika, it would seem that the first six generations… were not quite men or women as we understand the term at the present day, but were a species of man-god, or substantial water-spirit. (Gudgeon 1897: 180)

Today, just as Biblical accounts are now more fully recognised as metaphorical devices, Māori are more likely to present such stories as a way of thinking about the generative powers, the spiritual essence (mauri) of the non-human world, encapsulated in more abstract terms such as ‘living ancestor’ or ‘living entity’.

On both sides of the Tasman Sea, then, the landscape is the spiritual and material substance of human persons: just as the well-being of Māori people and their homelands is seen as mutually interdependent, Aboriginal elders in Cape York describe how people are ‘grown up by’ and composed of their country (Strang 1997). The well-being of both is so closely intertwined that negative impacts upon one are believed to have a detrimental effect upon the other. This intimate sense of interconnectedness, and the capacity to co-identify with non-human beings, is a powerful projection of personhood, and thus a substantial basis for describing a river as a legal person.

As indigenous communities have achieved an influential voice in conversations across global networks, ideas about more equal and collaborative relations with non-human worlds are coming to the fore, and now form the basis of much ethical debate. Some degree of co-identification with the non-human is implicit in some of the ideas outlined earlier: for example in the notion of the biosphere (Vernadsky 1986), in Lovelock’s Gaia theory (1987[1979]), or in the ‘connected by water’ vision of the Hypersea (McMenamin and McMenamin 1994). However, these are quite large and abstract concepts with rather less affective force than is provided by the ‘ancestral’ co-relations that form the basis of identity for many indigenous communities. In industrialised societies, then, the challenge is how to give real immediacy to ideas that reposition humankind more collaboratively amongst all living kinds.

Conclusion

As the ethnographic examples above suggest, a willingness to consider rivers as persons is more than an intellectual exercise. Enshrining non-human rights in law is fundamentally a statement of values, and—as relationships between beliefs and values and actions are recursive—a pragmatic view might be that to establish legal rights for rivers in the first place will initiate a relational shift. However, there is clearly a need to follow through by expressing these values in practice. The indigenous lifeways described above demonstrate that achieving more egalitarian and reciprocal human-environmental relationships means integrating such beliefs and values in all domains, including social and economic activities. In practice, for larger societies, this means that efforts to rethink relations with non-human beings must be accompanied by real striving to reduce the pressure of human needs and interests: by addressing population issues; by cutting excessive resource exploitation, and by eschewing short-termist capitalist ideologies and over-dependence on growth-based economic systems.

Here too, indigenous lifeways—though not replicable on a larger scale—can suggest some principles that might be applied to practical questions, for example in thinking about ways that water infrastructures are designed and employed. To change the ways that we engage with and make use of rivers is a large task, but thinking about them as living entities, and promoting their legal rights as persons, is surely a good place to start.

References

Atran, S. (1990). Cognitive foundations of natural history. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Bender, B. (1993). Landscape, politics and perspectives. Oxford, NY: Berg.

Bennett, J. (2009). Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Durham, NC, London: Duke University Press.

Berry, T. (2002). Rights of the Earth: Recognising the rights of all living things. In Resurgence, 214, https://www.resurgence.org/magazine/author2-thomas-berry.html.

Bicker, A., Pottier, J., & Sillitoe, P. (Eds.). (2004). Development and local knowledge: New approaches to issues in natural resources management, conservation and agriculture. London: Routledge.

Bord, J., & Bord, C. (1985). Sacred waters: Holy wells and water lore in Britain and Ireland. London, Toronto, Sydney, New York: Granada.

Brightman, M., & Lewis, J. (Eds.). (2017). Anthropological visions of sustainable futures. London, New York: Palgrave.

Chen, C., Macleod, J., & Neimanis, A. (Eds.). (2013). Thinking with water. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press.

Clark, A., & Chalmers, D. (1998). The extended mind. Analysis, 58(1), 7–19.

Coole, D., & Frost, S. (Eds.). (2010). New materialisms: Ontology, agency and politics. Durham NC, London: Duke University Press.

Cratylus. (n.d.). Works of cratylus. In Paragraph 401 Section d. Line 5.

Cullinan, C. (2003). Wild law: A manifesto for Earth justice. Totnes: Green.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. & Rochberg-Halton, E. (1981). The meaning of things: domestic symbols and the self. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dudley, N., Higgins-Zogib, L., & Mansourian, S. (2009). The links between protected areas, faiths and sacred sites. Conservation Biology, 23(3), 568–577.

Earth Law Centre. (2018). Universal declaration of river rights. https://therightsofnature.org/rights-of-nature-laws/universal-declaration-of-river-rights/.

Edgeworth, M. (2011). Fluid pasts: Archaeology of flow. London, Oxford, New York: Bloomsbury Academic Press.

Féaux de la Croix, J. (2014). ‘Everybody Loves Flow’: On the art of rescuing a word from its users. Suomen Antropologi: Journal of the Finnish Anthropological Society, 39(2), 97–99.

Gare, A. (1995). Postmodernism and the environmental crisis. London, New York: Routledge.

Glendinning, L. (2008). Spanish parliament approves ‘Human Rights’ for Apes. In The Guardian, June 26, 2008. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/jun/26/humanrights.animalwelfare.

Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature. (2018). http://therightsofnature.org/.

Gray, J., & Curry, P. (2016). Ecodemocracy: Helping wildlife’s right to survive. ECOS, 37(1), 18–27.

Gudgeon, W. (1897). The maori tribes of the east coast: Those inhabiting the Wairoa District of Northern Hawke’s Bay. The Journal of the Polynesian Society, 6(4), 177–186.

Haraway, D. (2008). When species meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Illich, I. (1986). H2O and the waters of forgetfulness. London, New York: Marion Boyars.

Ingold, T. (2000). Perceptions of the environment (p. 20). London, New York: Routledge.

International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). (2018). http://www.iucnredlist.org/about/summary-statistics.

King James Bible. (1611). Apostles 10, 42.

Kirksey, S., & Helmreich, S. (2010). The emergence of multispecies ethnography. Cultural Anthropology, 25(4), 545–576.

Krause, F. (2016). Making space along the Kemi River: A fluvial geography in Finnish Lapland. Cultural Geographies, 24(2), 279–294.

Kopnina, H. (2016). ‘Rejoinder: Discussing dichotomies with colleagues’ Special Forum: Environmental and Social Justice? The Ethics of the Anthropological Gaze. Anthropological Forum, 26(4), 445–449.

Kopnina, H. (2017). Beyond multispecies ethnography: Engaging with violence and animal rights in anthropology. Critique of Anthropology, 37(3), 333–357.

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor network theory. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Linton, J. (2010). What is water? The history of a modern abstraction. Vancouver, Toronto: University of British Colombia Press.

Lovelock, J. (1987[1979]). Gaia: A new look at life on earth. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lykke-Syse, K., & Oestigaard, T. (Eds.). (2010). Perceptions of water in Britain from early modern times to the present: An introduction. Bergen: BRIC Press.

McMenamin, M., & McMenamin, D. (1994). Hypersea: Life on the land. New York: Columbia University Press.

Milton, K. (2002). Loving Nature: Towards an ecology of emotion. London, New York: Routledge.

Morris, B. (2000). Animals and ancestors: An ethnography (pp. 31–69). Oxford, New York: Berg.

Muru-Lanning M. (2010). Tupuna Awa and Te Awa Tupuna: Competing discourses of the Wakiato River (Ph.D. Thesis). University of Auckland.

Naess, A. (1985). Identification as a source of deep ecological attitudes. In M. Tobias (Ed.), Deep ecology. San Diego, CA: Avant Books.

New Zealand Government. (1991). Resource Management Act. Parliamentary Counsel Office, Te Tari Tohutohu Pāremata, http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1991/0069/208.0/DLM230265.html.

New Zealand Government. (2014). Te Urewera Act. Parliamentary Counsel Office, Te Tari Tohutohu Pāremata, http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2014/0051/latest/DLM6183601.html.

New Zealand Government. (2017). Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River) Claims Settlement Bill. Parliamentary Counsel Office, Te Tari Tohutohu Pāremata, http://www.legislation.govt.nz/bill/government/2016/0129/latest/DLM6830851.html?src=qs.

Oelschlaeger, M. (1991). The idea of wilderness: From prehistory to the age of ecology. Newhaven and London: Yale University Press.

Plumwood, V. (1993). Feminism and the mastery of nature. London, New York: Routledge.

Plumwood, V. (2002). Environmental culture: The ecological crisis of reason. London, New York: Routledge.

Rolston, H. III. (2001). Natural and unnatural; wild and cultural. In Western North American Naturalist (Vol. 61, No. 3, Article 4). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan/vol61/iss3/4.

Roy, E. (2017). New Zealand river granted same legal rights as human being. In The Guardian, March 16, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/16/new-zealand-river-granted-same-legal-rights-as-human-being.

Ruru, J. (2013). Indigenous restitution in settling water claims: The developing cultural and commercial redress opportunities in Aotearoa, New Zealand. Pacific Rim Law and Policy Journal, 22(2), 311–328. http://www.digital.law.washington.edu/dspace-law/bitstream/handle/1773.1/22PRLPJ311.pdf.

Schläppy, M.-L., & Gray, J. J. (2017). Rights of nature: A report on a conference in Switzerland. The Ecological Citizen, 1(1), 95–96.

Serpell, J. (1996). In the company of animals: A study of human-animal relationships. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Singer, P. (1975). Animal liberation. London: The Bodley Head.

Stone, C. D. (1972). Should trees have standing: Toward legal rights for natural objects. Southern California Law Review, 45, 450–487.

Strang, V. (1997). Uncommon ground: Cultural landscapes and environmental values. Oxford, New York: Berg.

Strang, V. (2005). ‘Knowing me, knowing you: Aboriginal and Euro-Australian concepts of nature as self and other. Worldviews, 9(1), 25–56.

Strang, V. (2009). Water and indigenous religion: Aboriginal Australia. In T. Tvedt & T. Oestigaard (Eds.), The idea of water (pp. 343–377). London: I.B Tauris.

Strang, V. (2015). On the matter of time. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 40(2), 101–123.

Strang, V. (2017). Valuing the cultural and spiritual dimensions of water In Report to the United Nations High-Level Panel on Water.

Taylor, B. (2010). Dark green religion: Nature, spirituality and the planetary future. Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Tsing, A. (2004). Friction: An ethnography of global connections. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Tvedt, T., & Oestigaard, T. (Eds.). (2010). The ideas of water from antiquity to modern times. Tauris: London. I.B.

United Nations. (2018). Principles for water, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/17825HLPW_Outcome.pdf.

Vernadsky, V. (1986). The biosphere. Oracle, AZ: Synergetic Press.

Washington, H. (2013). Human dependence on nature: How to help solve the ecological crisis. London, New York: Routledge.

Washington Environmental Council. (2018). https://wecprotects.org/about-us/.

Washington State Department of Health. (2017). Environmental justice issues—Washington tracking network (WTN), https://www.doh.wa.gov/DataandStatisticalReports/EnvironmentalHealth/WashingtonTrackingNetworkWTN/Resources/EnvironmentalJusticeIssues.

Wills Perlo, K. (2009). Kinship and killing: The animal in world religions. New York: Colombia University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Strang, V. (2020). The Rights of the River: Water, Culture and Ecological Justice. In: Kopnina, H., Washington, H. (eds) Conservation. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13905-6_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13905-6_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-13904-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-13905-6

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)