Abstract

Peter Garber traces the crisis to three failed public sector projects launched in the late 1990s. These were a scheme to redistribute wealth by lending to uncreditworthy borrowers for real estate purchases in the US; China’s export-driven growth strategy; and the launch of the euro in 1999. The rapid increase in China’s exports to the US created a capital flow into the US and within the Eurozone, Germany exported goods to the southern periphery and German banks lent money to banks, businesses, and governments in the south. The effect of these flows was to drive global real interest rates to very low levels and this led to the expansion of the SPVs and SIVs, effectively ways of raising short rates for those who demanded it.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Which exogenous forces in the global system led to the crisis? Did it emerge from a financial bubble that popped, underpinned by implicit bailouts? Certainly, the subsequent reforms in the US stemmed from this belief. Or was it a constellation of government schemes that the financial system endogenously accommodated by whatever financial magic it could conjure to profit from implementing these policy imperatives. Aimed more at glitches in its grand project’s own institutions and government finances than at weaknesses in the private financial system, the reforms in the euro system imply this view.

Three Grand Projects

Three great public sector projects have driven global macroeconomic dynamics to this day. Launched or becoming systemically important at about the same time in the late 1990s, these were:

-

The US’s scheme to redistribute wealth by lending on a huge scale to uncreditworthy borrowers for real estate purchases. Judging from history, such a scheme had unpromising prospects for success.

-

China’s export-driven development program. This kind of program had been successful previously on a smaller scale in East Asia.

-

The launch of the euro. This grand project was a great leap of faith.

All were about the same order of magnitude of amounts bet. Each involved risking many trillions of dollars’ worth of capital, as is evident from the foreign exchange accumulation or money printing required to keep them afloat or subsequently to bail them out.

Two of these grand projects were geopolitical in intent or evolved into a geopolitical rationale. This explains the doggedness of the continuing official support for them. The US dollar system already was geopolitically dominant, but it had to absorb the capital flow implications of the other two programs. China, observing the accelerating weaponization of the dollar during the last ten years in the form of cutting off banks from the dollar payments system, suddenly and quickly moved to internationalize its currency in order to form the basis for a serious alternative. The euro zone itself has also demonstrated the devastation it can inflict through the payment system by cutting off countries like Cyprus and Greece, though this occurred on economic and technical grounds.

The US scheme collapsed first in 2007–2008, basically because the markets developed financial engineering methods in the form of credit derivatives to short the system. The US government was ultimately unwilling to keep its redistribution project propped up: it did not buy against the resulting short sellers of structured mortgage products. While the US came to its senses about its project, even the resulting global liquidity crisis did not force China and the EU to pull the plug on theirs. China intervened in its currency and equity markets, pressured lending to industries with excess capacity, and imposed controls so that its strategy is only now ending under US protectionist pressure. The euro experiment is in its tenth year of crisis against a European leadership determined to keep buying to keep it alive via rapid money printing in support of peripheral government finance. It is now facing secession and political rebellion in the weak countries against the programs implemented to shore up and advance the system.

Most macroeconomists had no strong views about the US housing finance until about a year before the collapse. Although it is the grand project that has been thought most likely to collapse by mainstream economists for more than a decade, the Chinese scheme is the only one that has not yet entered into crisis as it approaches its end-game. It may yet emerge with its original goals reached. Doubts about the long-term viability of the euro split the views of professional economists during the 1990s—usually taking the form of US versus European economists—but such doubts temporarily went into eclipse after the euro’s success in its early years.

Taken together, all these schemes generated huge cross-border and internal capital flows that drove long-term real and nominal interest rates to record low levels and without the usually simultaneous outbreak of unexpected inflation. It was the role of the financial markets to square the circle of packaging and channeling these flows. Given their own internal incentives, they did so with tremendous enthusiasm and obliviousness to risk and have been burdened with the social opprobrium of the collapse ever since. The progenitors of the great government projects at the root of the disaster have escaped such revulsion, however.

The Grand Projects, Real Interest Rates, and the Financial Sector Response

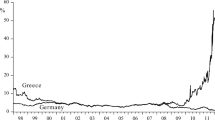

China-Asia’s/Germany’s and, later, commodity exporters’ net capital exports dominated the sum of these schemes. Even in the presence of a record global economic boom, this drove global long-term real rates to unusually low levels at every phase of the business cycle for more than a decade and to the present day. Long rates were matched by historically low short rates for the first five years of the millennium followed by the longest lasting inverted dollar yield curve in history (except the Volcker disinflation) until the crisis—the famous Greenspan conundrum.

The historical shift in interest rates meshed with various financial sector incentives to pave the road to the crisis via a scramble for yield. This was true for all financial sector players: buy side, sell side, politicians, regulators, rating agencies, and even the science and technology of finance in universities. Some institutions were constitutionally accustomed to the now defunct higher yield environment that promised clients unrealizable floors on their returns: insurance companies, private pension funds, and underfunded state pension schemes. Others promised themselves high returns: specialized German financial institutions looking for above market AAA, institutions with little reason to exist except the now-unavailable yield curve carry trade such as some Landesbanks, money market funds needing minimum returns to meet costs, platinum-standard university endowments, and large banks reaching for high ROE to keep up with peers.

The low short rates until 2005 led to the expansion of the SPVs and SIVs, effectively ways of raising short rates for those who demanded it. But the real explosion in such asset-backed commercial paper structures occurred during the two-year period of inverted yield curves. The carry trade could be continued for those institutions desperate to do so by financing even higher yielding, long-term credit risk suddenly converted to AAA. Where there is demand, financial engineering will create supply designed to satisfy the letter of regulatory constraints.

Private institutions with public guarantees, Fanny and Freddie were creatures of the US Congress. Driven to push housing credit to the maximum extent, they supported the major expansion of the subprime market. But the real estate boom was not confined to the US: UK, Irish, and Spanish banks and savings institutions drove mortgage markets to ultimate collapse without the use of US-style subprime. Others, such as those in Iceland, detached from serious regulation, offered clients above market deals in the old fashioned way, for example, by using offshore banks and branches that promised foreign depositors higher than market yields over the internet. They then channeled much of this to Iceland in the form of housing and infrastructure construction via huge and persistent current account deficits. Although many of the claims of foreign bond holders were defaulted, depositors were repaid in the resolution of the failed banks. However, Iceland kept its new infrastructure.

In the presence of the grand government projects, sell-side institutions were handed the problem of squaring the circle of the demands of the other players by sculpting and channeling capital in their usual creative way. Because of the sell side’s own distorting internal incentives, the financial engineering techniques provided by the science of finance allowed this to happen as long as liquidity was abundant.

Politicians in the countries receiving the huge capital exports had to find a way to keep their economies from recession. In the US, Ireland, and Spain, they resorted to housing investment, devoting an increased share of the economy to construction; and therefore they encouraged massive lending from the domestic institutions in the mortgage market. In Greece, they directed the inflow to favored local populations to encourage consumption and to government employment, which created the façade of production. To keep export surpluses flowing, German financial institutions, especially those controlled by Landes politicians, acquired problematic types of paper on offer from abroad ranging from sovereign bonds of the euro periphery countries to US sub-prime paper. In the UK, industrial policy to enhance the scope of the City, then the most important UK industry, had political primacy. Regulation was separate from the Bank of England and captured by financial industrial policy priorities of the government and therefore the FSA.

Regulators in the EU were under national political authority, so they were not averse to encourage actions that were detrimental to the larger interests of the EU or euro zone. For example, Spanish regulators hesitated to control the lending of their savings banks to the overheated housing market. Greek, Italian, and Spanish regulators encouraged their banks to buy local sovereign debt to finance themselves ultimately via the liquidity guaranties of the euro central banking system. They did not hesitate to conflate a local sovereign crisis into a system-wide monetary crisis. Cyprus was well known as a Russian money laundering operation, but nothing was done to prevent this. Finally, regulators encouraged financial engineering methods of risk management: value at risk, mark to market and accepted the banks own models. Such methods exacerbated the liquidity crisis when volatility exploded.

It was not better in the US. Politicians pushed Fanny/Freddy to lend to the uncreditworthy, thereby using them as non-appropriated fiscal operations, which ultimately had to be admitted in the federal government fiscal accounts in the bailout. This satisfied both the redistributionist impulse of a controlling or at least blocking political party, the Democrats, and the desire of the Republicans to recover from the 2001 recession. The Federal Reserve, the principal regulator of the banks, also pushed the banks to lend to the uncreditworthy, with threats to charters or branches and public shaming and lawsuits for the recalcitrant. Mortgage origination itself was a regulatory responsibility of the states, and like almost all state financial regulation, it ranged from lax to non-existent.

Product development via financial engineering was pushed by business schools and economics departments. The theory and practice was almost always developed and sold under the assumption of perfect liquidity, because there was really no theory of derivative pricing in illiquid markets. Only after the collapse did they emphasize that liquidity is crucial for these schemes to work. Business school finance departments boomed producing this product, and their students were sold to the financial industry at high levels of compensation. Finance professors gained high incomes via revolving doors with hedge funds and banks as advisers and fund managers on the basis of this work.

Conclusion

There are several possible causes of the collapse and Great Recession. In the US, perhaps it was the housing collapse per se that drove the real recession. Perhaps, it was the liquidity panic that collapsed the financial system. Maybe several dimensions of bubble mentality in the financial system caused the sparked the demise. But before locating the source of the problem in the proximate causes or in characterizing the event entirely as a financial bubble, it is first necessary to understand just which fundamentals set the events in motion. Were these fundamentals in themselves benign? Or did they drive the financial system into the liquidity and derivative contortions that broke with the collapse of Lehman? Did the authorities acquiesce or encourage these financial fixes to advance their own economic policies? Was the housing policy in the US itself a spontaneous outburst or redistributionist spirit, or was it fostered by both parties as the boost in internal investment that would offset the deflationary macro impact of the current account deficit?

Perhaps, the housing gambit was the only way of staving off the recession in the face of deflationary pressures from abroad—without it the recession may simply have arrived a few years earlier. With a fall in the real rate of interest caused by the capital flow implications of the grand projects, we would expect an internal investment boost as the formerly marginal projects along the marginal efficiency of investment curve now became viable. But which investments would these have been? Certainly, not those in manufacturing—the current account deficit reflected the flood of cheap manufactures pouring into the US and the movement of manufacturing capital and management out of the US. Nor was the displaced Labor being absorbed as much as one would normally have expected in the service industries—immigrant Labor poured in at low wages, and clerical jobs were offshored. So housing seemed to be the only outlet. But to make the housing boom work, there was a need to find new buyers and move down the chain of creditworthiness. So was born the financial magic. In Europe, the current account of the euro zone was in balance overall, but this hid the deficits in the south and the surpluses in the north. The south faced goods inflows both from Germany and East Asia with the inability to use currency depreciation to block them. So where did they invest to fight the deflationary impact? Housing in some places, government transfers and early retirement in others. All this proceeded through the creative finance and implicit backstops of the euro system.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Garber, P. (2019). Three Grand State Projects Meet the Financial System. In: Aliber, R., Zoega, G. (eds) The 2008 Global Financial Crisis in Retrospect. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12395-6_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12395-6_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-12394-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-12395-6

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)