Abstract

Assisting professionals to care for those with major neurocognitive disorders (MNCD), including the inevitable neuropsychiatric symptoms, using the person-centered philosophy is the goal of this text. After a review of the history of person-centered care planning, a model to assess/evaluate a person’s behavioral communications is presented. The viewpoint for all care starts with a strength-based assessment of the person living with dementia. The framework makes use of the supported decision-making paradigm. After assessment, there is a review about choosing and applying person-centered interventions using regular monitoring of outcomes.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Person-centered

- Strength-based

- Care planning

- Assessment

- Neuropsychiatric symptoms

- Dementia

- Major neurocognitive disorder

- BPSD

- Behavioral disorder

Person-Centered Care and Care Planning

The fundamental philosophy underlying person-centered care is to create a human relationship between people living with neurocognitive disorders and those who care about and for them (both family and care providers). The personal, rather than clinical, relationship is central to creating a paradigm shift in how we care for people living with dementia. This relationship extends to the family and other natural supports of those living with dementia.

The philosophical notion of being present – human to human – and understanding another’s experience is central to caring for those living with dementia. Often people living with dementia struggle to share who they are as a person and require assistance of healthcare providers to develop a trusting relationship. Ideally, the care plan is a living document written from the person living with dementia’s viewpoint, outlining the person’s goals and steps the person, their family, and professional staff will take in efforts to meet them.

The care planning process enables the interdisciplinary team to understand a person’s desires and needs, and the care plan document offers a vehicle to communicate with the person living with dementia and their family. Every care plan should be individualized and focused on meaningful engagement. Care should be relationship-based, with an emphasis on promoting a positive engagement. Information needs to include the person’s physical needs, personal values, daily routines, sources of meaning, and enjoyment. When someone has moved from their own home into a facility, a care plan and staff training are required to assess staff needs, resources, satisfaction, and person-centered communication abilities [12].

Provider-based treatment plans as seen in Table 9.1 are based on a medical model. Patients present with symptoms, syndromes, and diseases, the provider performs an assessment and develops a working diagnosis which leads to the plan. The viewpoint is the clinician’s, and the language is specific to a specialty of medicine. The assessment and plan are written solely by the provider. Nursing care plans, rehabilitation care plans, and others use an analogous model. The patient is passive, while the clinician acts on the patient.

Treatment teams, such as inpatient psychiatric care and inpatient rehabilitation units, often include a multidisciplinary team (MDT). The MDT members each perform assessments from their own discipline’s perspective and contribute individually to the treatment of the patient. MDTs then develop a treatment plan, which consists of diagnoses or problems, and each discipline addresses the problems separately. Generally, every member of the MDT signs the treatment plan which is then presented to the patient for their signature, although there is little or no negotiation with the patient. The MDT model is similar to the provider-based model, but with a greater number of disciplines. A true interdisciplinary team (IDT) model integrates the MDT model into a matrix of collaboration, as discussed in an earlier chapter in this book.

In contrast, service-based plans are frequently used in assisted living facilities (ALF), underscoring the view of the individual as a customer. Commonly, a service plan has a column with particular services to be provided to the person living there: nursing services, medication administration, dining room services, laundry services, etc. This is followed by a column listing the frequency of the service, who will provide the service, and sometimes a space for individual information or comments. The service plan is set up to easily tally the cost of the package of services being delivered to the person living there. Generally, a manager will sign the service plan as well as the ALF resident. A resident has certain rights and can negotiate some aspects of the service plan, but ultimately the management has final decision-making power as landlords.

Person-centered care planning, an example of which is in Table 9.2, is required by federal regulation in nursing facilities. The authors of this text recommend that every person living with dementia will benefit from having their own personalized care plan. This document can be used as an aid to communication between the person and family as well as introduction about the person for professional caregivers and clinical staff. Ideally, those living with dementia will have access to an IDT with whom to collaborate for their care planning as outlined in the earlier chapter on IDTs. The members of a person’s IDT will vary depending on their particular needs, where they live, and what resources are available. The key to a high-functioning IDT is the collaboration and combination of insight and thought leading to planning that supports the decisions of the person living with dementia, utilizes their strengths, and meets the needs of the person.

Person-centered care for those living with dementia is most effective when care is informed by individual strengths. The role of the care plan and the care planning process is particularly important for those living with MNCD. First, this group of individuals has a limited ability to speak for themselves, particularly when undergoing a transition. Second, the ability to communicate verbally is likely to decrease over the course of the disease process. Finally, neuropsychiatric symptoms place the individual living with dementia at elevated risk of needing a higher level of care due to increasing care needs. When the person arrives with their current care plan, the ability to orient and engage the person at admission to a new facility or when starting with a new provider will be greatly enhanced.

Cultural influences, personal motivations, and meaningful activities must all be considered. When first introduced, patient-centered care was viewed as practitioners seeing patients as individuals and empathizing for the unique perspective and experience [1, 13]. The initial development of person-centered care has evolved into the direct connection for care planning and training caregivers of persons living with dementia.

Additional studies support caregiver training and patient-centered interventions that directly target common neuropsychiatric symptoms. Agitation, a neuropsychiatric symptom sometimes driven from unmet needs, has been shown to be decreased with person-centered activities and treatment plans [5]. Doody et al. [21] report grading tasks, toileting schedules, and cues to complete self-care as a best practice approach for dementia. Kverno et al. [11] concluded that individualized schedules that assist with arousal states and environmental adaptations are the strongest interventions in a systematic review of non-pharmacological interventions for people with advanced dementia. Spijker et al. [20] recommend consistent caregiver intervention with high ability and intensity to delay institutionalism. Caregiver training has been shown to be the most recommended approach to provide care for people living with dementia [8, 11, 22].

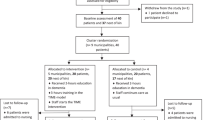

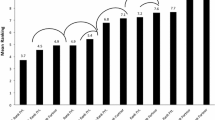

Person-centered care has several essential elements: understanding individual life history and needs, knowledge of family and other natural supports involved, providing meaningful activities, and adapting environmental demands [10, 14]. In the model proposed in this book, evaluation of strengths is conceptualized as rooted in skilled evaluation. After an evaluation is completed to identify a person’s life history, strengths, challenges, and current supports, a care plan should be developed based on the causes of neuropsychiatric symptoms and personal motivations for engaging in meaningful activities. Figure 9.1 outlines a clinical reasoning process for care plan development. Integral to this model is staff education, use of quality of life measures (not just poor outcome measures), documentation, and continued regular review.

In a comprehensive review of guidelines published after 2009 around person-centered guidelines, Maloney [12] noted six areas where routine assessment is recommended: cognition, functional status, neuropsychiatric symptoms, medical status, living environment, and safety. Recommendations about frequency of assessment and reassessment of NPS are varied but generally recommended every 3–6 months and when there is a notable. Functional and medical assessments are recommended every 6–12 months and whenever there is an increase in NPS [12]. Other areas that are recommended for routine assessment include goals of care, driving, home safety, and use of substances [3]. The authors of this text recommend that every IDT’s care planning start with the goals of care for a person. It is essential that all assessments and interventions take the individual’s goals of care into consideration.

Identify and Assess Neuropsychiatric Symptoms and Interpret the Communication Embedded in Behavior

Neuropsychiatric Symptoms (NPS) Versus Psychiatric Illness

As reviewed in earlier chapters, NPS are ubiquitous in those with MNCD. The importance of distinguishing between symptoms and illness should be underscored. Those individuals with a history of significant mental illness such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder (BD), and major depressive disorder (MDD) have a significantly higher risk of developing MNCD than the general population [4, 9]. Therefore, the care plan is essential to provide a past history of illness, as well as vital information on how the episodes have presented in the past.

The importance of the individual care plan is essential for individuals with concurrent neurocognitive and psychiatric illness. The standard of care for psychiatric illness must be at the forefront of care, even if there is a potential conflict with institutional or regulatory guidelines. The pressure to decrease unneeded psychotropic medications in those with MNCD is appropriate overall but may cause unintended consequences for individuals with concurrent psychiatric illness. The current focus is only on what the percentage of use of a class of medications. This is misguided and the opposite of individualized and person-centered care. The goal should be appropriate use and nonuse of medications. Avoiding the use of a needed medication because CMS publicly reports the percentage of people being given that medication is diametrically opposed to person-centered care, the right medicine to the right person at the right time, and the right intervention to the right person at the right time – this is the triple aim of modern healthcare.

For example, the current standard of care for treatment of recurrent major depressive disorder (MDD) recommends indefinite treatment with the antidepressant regimen that enabled them to be stabilized. In some cases, the mediations may be tapered, but the individual with MDD will still require monitoring for at least 1–2 years and perhaps longer. This individual’s care plan will therefore highlight the need for these medications to remain unchanged, unless there is a pressing clinical concern. This is not the person for whom a routine gradual dose reduction (GDR) is likely to succeed; in fact, an unaware or routine reliance on GDR protocols may directly cause psychiatric decompensation, extreme suffering potentially including suicide, loss of placement, loss of friendships and other relationships, financial hardship, etc.

Similarly, someone with schizophrenia generally should continue on antipsychotic medications for at least 5 years after their last symptoms [2], which may potentially conflict with institutional guidelines for GDR. If all symptoms are not in remission for 5 years, then GDR is contraindicated. If symptoms reemerge after medication doses have been lowered or discontinued within the last 5 years, antipsychotic medications must be restarted or titrated back to previous doses. Individuals with preexisting psychiatric illness deserve to have their illness treated without exposure to the risk of suffering that accompanies decompensation simply because they also have dementia or have to live at a certain level of care.

Anxiety can serve as both a symptom and a disorder. Anxiety is a common neuropsychiatric symptom affecting individuals with MNCD. Anxiety is also a class of several disorders, as seen in illnesses such as generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) or panic disorder. Assessment and treatment of anxiety as an NPS is clinically different than assessment and treatment of an underlying anxiety disorder.

When an individual living with MNCD also has an underlying anxiety disorder, symptoms of anxiety should be evaluated in that context. If the symptomology is like past episodes of the anxiety disorder or meets current criteria for a particular anxiety disorder, then it would be reasonable to treat the symptoms as a relapse or occurrence of the underlying disorder, including a trial of medications that have been useful in the past. On the other hand, anxiety can occur as a nonspecific reaction when the environmental demands and expectations exceed a person’s abilities, which is quite common in individuals living with MNCD. People living with dementia also experience anxiety when feeling overwhelmed about the changes in their brain functioning. These types of NPS-related anxiety symptoms are often best treated supportively with environmental modifications, supportive care, and reassurance. Dementia-specific medications can also be helpful for this symptom when it is caused by the MNCD rather than a specific anxiety disorder.

Similarly, depression serves as both a symptom and a disorder. Major depressive disorder (MDD) is common in the population as a whole, particularly in women. Depression as a single symptom is also a common NPS in those with MNCD and occurs frequently in individuals with vascular dementia as well as MNCD due to Lewy bodies or Parkinson’s disease.

Psychiatric medications have less utility in NPS, as most medications have been designed and tested in younger adults with specific psychiatric illnesses and syndromes rather than in older adults with MNCD. For example, antidepressants are an important part of treatment for MDD but less helpful for depression as an NPS. Symptoms of sadness and grief are common human emotions and will not respond to an antidepressant.

There is evidence for use of psychiatric medications for some NPS. This needs to be reviewed individually. Some NPS in MNCD respond to dementia-specific medications, while others do require psychiatric medications. All NPS occurring in those living with dementia do arise from the neurological system as do all psychiatric illnesses. A clear diagnosis and plan for a medication trial includes monitoring symptoms, preferably with a formal scale such as the NPI-Q, stopping medications that are not helping and routine monitoring of side effects. All medication use, psychiatric and otherwise, requires an informed consent process. Risks and benefit calculations for a person will be affected by the person’s particular goals of care [19].

Recognizing Communication Embedded in Behavior

It is important to observe and describe the behaviors exhibited by individuals living with MNCD. Behavior is communication, and recognition and categorization of behaviors enables interpretation of the message. As described in the chapter on pain, physical distress is commonly expressed by crying, pacing, clenched fists, and hitting and pushing caregivers. Similarly, anger and aggression may reflect fear or shame [17, 18]. Looking for the underlying emotional expression is an essential part of the evaluation process. The individual with MNCD may be exhibiting characteristics of anger, but the clenched fist may actually be driven by fear, pain, confusion, etc. Dealing directly with the fear is a better strategy and much more likely to succeed than focusing on the anger itself. Exploring the accompanying emotional expression is imperative.

Identify Unmet Physical and Emotional Needs

Neuropsychiatric symptoms provide a way to communicate unmet needs for individuals living with dementia. Caregivers should be encouraged to identify all basic needs when trying to decipher behavior as communication. Physical needs include hunger, thirst, need for toileting, and relief of pain. Emotional needs may include searching for familiarity, seeking safety, and looking for meaningful activity or human contact. This has been explored in the earlier chapter on ADL care. That chapter was a guide showing how to use the strength-based person-centered interdisciplinary approach to care for a person living with dementia.

Drive for Meaningful Activity

Most people fill their days with productive work. Work is not exclusive to earning a wage and includes activities such as pet care, child rearing, housekeeping, or cooking [23]. Dementia potentially robs the individual of the ability and skills to participate in meaningful activity. To fully understand this devastation, the caregiver must understand that dementia is much more than memory loss; rather, it affects all parts of the brain. As described in previous chapters, all cognitive domains are needed to carry out daily tasks. It is commonly assumed that if a person has done something all their life, they will remember how to do it. For example, a gardener will remember how to plant, a housekeeper will remember how to clean, and a mother will know how to cook a family meal. However, the process of remembering is not the sole problem with advanced dementia. The caregiver must understand and appreciate the complexity of the various skills required for completion of a task. With advanced dementia, the gardener may enjoy the feel of the dirt, but may not be able to understand what he sees. The housekeeper may continually scrub the counter, but not understand the use of supplies or results of her actions. The mother may unable to start the task or sequence the actions required to cook the traditional meal.

The inherent drive to be engaged in the world is an essential, universal part of being. Although the definition of meaningful activity may change, it is essential for people living with dementia to remain as active and connected as possible [15]. It is also essential that caregivers view activity as meaningful [16].

Cognitive dysfunction may affect skills, but the drive for familiar and purposeful activity persists. The gardener may pull out plants, the housekeeper may scrub a clean wall with a shirt, or the mother may become frustrated and throw ingredients on the floor. How the caregiver views and supports these activities can create meaning and transform them into purposeful activities.

Cognitive Domains and Strength-Based Assessments

The DSM-5 cognitive domains outlined in Fig. 9.2 provide healthcare providers with a common language to describe and communicate about cognitive domains. By understanding assessments from this point of view, health professionals can complete an evaluation that is strength-based, as well as identify interventions that meet the needs of the skill loss that is driving the behavior or challenging activity participation. Chapter 4 of this text provides an in-depth review on how to use cognitive domains to arrive at strength-based assessments for person-centered care.

Applying Interventions

As a caregiver, it is important to encourage participation in activity that follows the habits and routines that existed prior to the onset of dementia. The following are some simple ideas that can encourage productive activity in people living with dementia:

-

Avoid power struggles.

-

Choose engagement over expectation.

-

Simplify and understand activity demand.

-

Understand evaluation and progress.

Avoid Power Struggles

Simply stated, a caregiver will never win an argument with someone living with dementia. The same neurocognitive process that affects memory and executive function also affects insight. The greater the neurodegeneration, the greater the dysfunction. If the individual living with dementia is unable to comprehend their own behaviors or actions, it is unlikely that they are able to comprehend feedback about the rightness or wrongness of those behaviors or actions [7]. Constant redirection or feedback is therefore perceived as negative.

The distress of living with dementia can be analogous to constantly negotiating an unfamiliar and challenging environment. It is essential to teach caregivers to create safe and structured environments in which the autonomy of the individual with MNCD is supported. An environment that is set up to allow ample participation in activity decreases the need for redirection. Limiting the need for caregiver interference can decrease caregiver burden [6]. An important caregiving philosophy is the understanding that the person living with dementia may not be capable of change, but the caregiver is.

Case Example John: Occupation Stations

John is a 74-year-old male with vascular dementia. After suffering a series of strokes, John presented with loss typical of damage to the parietal, temporal, and frontal areas of his brain. Because of this damage, motor planning, sequencing familiar task, and language skills were lost. Despite some memory skills, his perceptions of sensory stimuli were distorted. Aphasia (impaired language ability) and apraxia (inability to sequence steps for an action) were profound. Self-care could be completed as long as supplies were simplified and routines were cued. In returning from the hospital, he was unable to work a remote control, answer a telephone, or work in his garden. An avid outdoorsman, he loved to fish. He also loved puzzles and prided himself in keeping the house clean alongside his wife. Due to subcortical damage, sleep regulation was difficult for John, and he could not keep track of time. Unable to read a clock, he was focused on time and schedules. He would often get up in the middle of the night and dress. Still mobile, he had unsteady gait and poor endurance. Scared of injury from falls and wandering, his wife sought a home safety evaluation.

John was friendly, but frustrated. He allowed the therapist to complete a home assessment. He appeared to enjoy the conversation, but was irritated with word loss and often would hit his fist on the table. He showed some emotional deregulation, with tearfulness and then laughter. The occupational therapist identified John’s main concern was the loss of meaningful activity. His wife’s main concerns were safety, specifically falling or getting lost. John was frustrated with his loss of abilities and believed his wife trying to control him. In effort to increase John’s occupational engagement, the occupational therapist set up occupation stations within walking distance from his bedroom. He had frequent places to sit, had limited hazards, and could move from station to station without falling. In one corner there was a simplified area to tie flies with feathers, string, and objects to sort in large tackle boxes. In the next area, there was a half-done puzzle with large pieces and reader glasses. There was an area to stack, move, and look at magazines in familiar topics with pictures. Mail addressed to him was placed on a desk as well was a large planner that had no appointments marked in the today slot. There was no easy path to the door, and all locks were installed high on the doors and painted the same color. The bathroom door was left open. The bathroom was free of clutter but with grab bars and a night light.

Many nights, John would get up and move from station to station engaging in familiar, yet simplified, activities without falling and without the need of his wife to supervise or assist.

Choose Engagement over Expectation

Dementia is a progressive, terminal illness that places high demands on caregivers. Permission to enjoy time with the person living with dementia is essential for everyone’s well-being. Many caregivers have an expectation of task performance. For example, if they cook with a person with a dementia, there is an underlying belief that the process should not be a mess and the food should taste good in the end. There is an expectation of a good product from activity.

Caregivers can decrease this frustration by learning to perceive activity as a journey. Viewing activity as a process to be enjoyed, or a road trip without a destination, can change the meaning of an occupation. If a caregiver is too busy looking at a map for a place that does not exist, they will miss all the scenery along the way. Professional caregivers need to be given permission to build relationship with individuals and engage in person-centered care.

Creative Janet: Too Many Cooks in the Kitchen

Janet’s husband, Walter, was caring for her without assistance in the home. Janet had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia for 7 years. She no longer kept track of days or remembered the age of her children and would wander without supervisions. Over the past year, Walter had to be home 24 hours a day and assist Janet with self-care tasks, such as picking out clothes, hygiene in the shower, and nutrition. Janet had always been a homemaker and made the meal, so cooking was new to Walter who was frustrated by her spilling and mixing of odd foods. Walter was devastated by the decline in Janet’s function and her loss of skill, as she had always been such a good cook. Frequently, Janet told him his food tasted horrible and tried to help in the kitchen. She became angry at Walter for interfering with mixing and creating food. She yelled at him for not shopping and buying the correct items. He would not let her use the stove.

During a family visit, Walter and Janet’s daughter brought premade pie dough. She spread the flour on the counter and asked for Janet’s help. Janet immediately began to knead and roll out the piecrust. Laughing and talking, the flour got on her face, the floor, and both their clothes. Janet tasted the piecrust and said it needs more ingredients. She began adding as she saw fit, rolling and pressing the dough. Quietly, Dorothy put a pie together next to her mom and set it in the oven with her mom’s approval. As the kitchen smelled like pie, they pressed the overhandled piecrust in a pan and set it aside. Out of sight and mind, they cleaned together as the kitchen smelled like pie. Walter was amazed by the amount of laughter coming from Janet and how happy she appeared as the pie came out of the oven.

Simplify and Understand Activity Demand

Underestimating the steps to complete an activity is a common occurrence and can lead to distress. Congruently, overestimating the ability of a person living with dementia can lead to an increase in neuropsychiatric symptoms. Dementia often looks good but performs badly – meaning that persons living with dementia do not look impaired and often surprise caregivers with their lack of ability. Persons with advanced dementia often lose insight and can overestimate their own abilities. Confabulation, filling in the blanks, and trying to make sense of the world during conversation can mask the true level of confusion. When persons with advanced dementia attempt to carry out a functional activity with multiple steps, the impairment may become more evident. The key is to find the just-right challenge. The just-right challenge identifies an activity demand where a person with cognitive impairment can participate in a meaningful way.

To identify the just right challenge consider a quick functional evaluation. As seen in Table 9.3, utilize the informal 3 × 3 assessment. Start by providing three objects and three steps, and observe how the person negotiates a familiar and interesting task. For example, if cooking is an interest, provide them with pot, a can of soup, and a can opener. Clear the counter and ask for their help. Watch as they negotiate the tools and objects. Can they name them? Can they use them in the right order? Can they initiate and terminate activity? If it is too difficult, try to simplify and provide a 2 × 2 assessment, comprised of two steps and two items, and an invitation to “open the can and pour it in the pot.” If it is too difficult, lower the complexity to a 1 × 1 assessment, such as “stir the soup.” Take note of any observed frustration. A consult with an occupational therapist can assist in identifying the just-right challenge as well as completing an activity analysis on familiar tasks.

Creating A Fancy Garden: The Work Is Never Done

In developing a therapy garden at work many years ago, an occupational therapist started with a small chunk of grass that was turned into a manicured ADA accessible site with wheelchair accessible paths, sensory gardens, and raised beds for horticultural therapy activities. The therapeutic value of the garden was expressed in presentations that focused on how persons living with dementia could escape the institutional walls of the hospital and experience the calmness and healing power of the garden. When opened, it was beautiful.

As time passed, staff discovered the majority of the participants were too confused to participate in purposeful gardening. They would pull out flowers, water the sidewalk, and climb the fence. The garden slowly looked less manicured, less presentable, and less inviting to families and visitors. However, that is where the real work began. In taking people with advanced dementia outside simply for fresh air and exercise, the staff discovered it mimicked a run-down backyard. Older gentlemen with moderate levels of dementia could not resist the urge to pick up a rake or broom and begin to clean up. Others began pulling the dead heads off of flowers, putting on gardening gloves, and watering dying flower pots. People had long conversations about work to be done. People painted fences. People moved pots. Sometimes we planted and pulled things out in the same day. It was not the power of nature. It was the power of occupation. For those with memory loss, many do remember working. They remember working in their yards and chores that were never done, so they saw work and began to engage.

Consider setting up unfinished projects that might inspire people living with dementia to engage in meaningful tasks.

Activity becomes purposeful when an individual perceives that they are accomplishing something. Product is not important living with dementia, process is. Caregivers must be taught to let go of expectations that work will produce product or that all actions will be goal-directed. Taking apart an already broken appliance in a garage may be quite enjoyable to an individual with a mechanical tendency. The same activity may produce distress for an individual that is not mechanically inclined.

Concentrating on past interests and skills may provide opportunities to participate in similar activities. The trick is to simplify yet retain the meaning. For example, a post office worker may become enthralled with stacking and sorting mail. In contrast, an artist does not necessarily want to use crayons in a child’s coloring book. Presentation of activity is essential. The provision of activities that allow for perceived independent choice increases occupational engagement (Table 9.4).

Person-centered care plans contain a number of components. Each clinical discipline will do an assessment and develop a person-centered plan based on their discipline’s requirements and the standard of care. The care team will then meet together with the person living with dementia, the family or natural supports, and all the team members. Discussion centers on where the person has “travelled” in their life and their disease since the last care plan meeting, what the current state of the person is, and what the future is likely to hold. This is the time for every team member to contribute information about any challenges that may be occurring and for sharing strengths and resources that are appropriate for the person. The person living with dementia and family are provided the opportunity to ask questions and dialog with team members. The interdisciplinary care plan is negotiated, signed, and disseminated to the person living with dementia, their family, and the team. Regular reassessments and updates to the care plan are recommended and if there is a significant change in the person’s condition.

References

Brooker D. What is person-centred care in dementia? Rev Clin Gerontol. 2003;13(3):215–22.

Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, Noel JM, Boggs DL, Fischer BA, Himelhoch S, Fang B, Peterson E, Aquino PR, Keller W, Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT). The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):71–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbp116.. Epub 2009 Dec 2.

Callahan CM, Sachs GA, Lamantia MA, Unroe KT, Arling G, Boustani MA. Redesigning systems of care for older adults with Alzheimer’s disease. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(4):626–32. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1260.

Cai L, Huang J. Schizophrenia and risk of dementia: a meta-analysis study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:2047–55.

Chenoweth L, King MT, Jeon YH, Brodaty H, Stein-Parbury J, Norman R, et al. Caring for Aged Dementia Care Resident Study (CADRES) of person-centred care, dementia-care mapping, and usual care in dementia: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(4):317–25.

Brodaty H, Arasaratnam C. Meta-analysis of nonpharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(9):946–53.

Cohen-Mansfield J, Jensen B, Resnick B, Norris M. Knowledge of and attitudes toward nonpharmacological interventions for treatment of behavior symptoms associated with dementia: a comparison of physicians, psychologists, and nurse practitioners. Gerontologist. 2012;52(1):34–45.

Cooper C, Mukadam N, Katona C, Lyketsos CG, Ames D, Rabins P, et al. Systematic review of the effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions to improve quality of life of people with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;1(1):1–15.

Da Silva J, Goncalves-Pereria M, Xavier M, Mukaetova-Ladinska E. Affective disorders and risk of developing dementia: systemic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;202(3):177–86.

Edvardsson D, Fetherstonhaugh D, Nay R. Promoting a continuation of self and normality: person-centred care as described by people with dementia, their family members and aged care staff. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(17-18):2611–8.

Kverno KS, Black BS, Nolan MT, Rabins PV. Research on treating neuropsychiatric symptoms of advanced dementia with non-pharmacological strategies, 1998-2008: a systematic literature review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(5):825.

Molony SL, Kolanowski A, Van Haitsma K, Rooney KE. Person-centered assessment and care planning. Gerontologist. 2018;58(suppl_1):S32–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx173.

Nolan MR, Davies S, Brown J, Keady J, Nolan J. Beyond ‘person-centred’ care: a new vision for gerontological nursing. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13:45–53.

Phinney A. Family strategies for supporting involvement in meaningful activity by persons with dementia. J Fam Nurs. 2006;12(1):80–101.

Phinney A, Chaudhury H, O’connor DL. Doing as much as I can do: the meaning of activity for people with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(4):384–93.

Roland KP, Chappell NL. Meaningful activity for persons with dementia: family caregiver perspectives. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2015;30(6):559–68.

Velotti P, Garofalo C, Bottazzi F, Caretti V. Faces of shame: implications for self-esteem, emotion regulation, aggression, and Well-being. J Psychol. 2017;151(2):171–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2016.1248809.

Williams R. Anger as a basic emotion and its role in personality building and pathological growth: the Neuroscientific, developmental and clinical perspectives. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1950. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01950.

Nash M, Swantek SS. Neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: monotherapy, or combination therapy? Curr Psychiatr Ther. 2018;17(7):21–5.

Spijker A, Vernooij-Dassen M, Vasse E, Adang E, Wollersheim H, Grol R, Verhey F. Effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions in delaying the institutionalization of patients with dementia: a meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(6):1116–28.

Doody RS, Stevens JC, Beck C, Dubinsky RM, Kaye JA, Gwyther L, Mohs RC, Thal LJ, Whitehouse PJ, DeKosky ST, Cummings JL. Practice parameter: management of dementia (an evidence-based review): report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001;56(9):1154–66.

O’Neil ME, Freeman M, Christensen V. Non-pharmacological interventions for behavioral symptoms of dementia: a systematic review of the evidence, VA-ESP Project# 05–22: 2011; 2012.

AOTA. Occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process (3rd Edition). Am J Occup Ther. 2014;68(Supplement_1):S1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendix A: Sample Interdisciplinary Care Plan

Background Information

Date of report: January 12, 2019 Client’s name or initials: AM

Date of birth: 6/24/1934, although patient is unable to report

Reason for care plan update: Change in condition – reassessments completed by all members of the team, now working on interdisciplinary care plan for AM

Profile

AM is an 84-year-old woman who has lived in a memory care facility for the last 3 years and has severe MNCD. AM is able to answer to her name but has decreased verbal generative fluency. She smiles and nods her head in greeting, but does not engage in conversations. She follows the housekeeping staff around during the day. Her family believes that AM enjoys watching cleaning when it is done well. They report similar behavior in AM’s younger years; she liked keeping the house clean when her children were young. She also liked to cook, but hasn’t done any cooking for the last 20 years.

Change in Condition

AM’s behavior began to change about 3 weeks ago. She frequently becomes distressed, screaming at staff and chasing people who come into her room. These episodes occur on an almost daily basis, typically in the late afternoon. She takes several hours to calm down when she becomes upset. She has lost 17 pounds in the last 4 months. No precipitating factors or changes at the memory care unit have been identified. Her daughter’s visit frequency is about the same.

Life factors influencing current condition

-

Per family, AM would not have described herself as a religious person.

-

Homemaker, kept a spotless house, was an excellent cook.

-

Liked getting her nails done, has not been able to sit for this in the past 6 months.

-

Loved to travel.

-

Husband was an artist.

-

One daughter is married with a grown child of her own, lives near the Memory Care Unit, and visits most days.

Assessments

Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Q form: score – severity 14, caregiver distress 18.

Aggression 3/4, depression 3/5, anxiety 3/5, irritability 2/3, eating 3/2

MSSE: score of 7 – not calm 1, screams 1, malnutrition 1, eating problem 1, invasive actions (CBG) 1, suffering according to medical opinion 1, suffering according to family 1

Domain

Goals of care/end-of-life issues: Now in a palliative care, comfort care track

AM perspective: “No pain” was the last conversation about this, which occurred approximately 2 years ago. She has not been able to verbally provide additional input, although she has been communicating distress with her behavior.

Daughter: Family supports a focus on comfort. They are unsure what might be causing AM’s current outbursts.

Interdisciplinary team: Focus is on keeping AM comfortable and minimizing pain. Consideration is being given to current increase in distress and whether it is related to pain. Team is pondering if AM has started the transition to the end of life and estimates the trajectory over the next 1–2 months. MSSE suggests life expectancy of 6 months or less. Referral to hospice services is recommended to AM and her family.

Participant perspective | Issues | Plan | Discipline |

|---|---|---|---|

“No pain” was the last conversation about this, 2 years ago | GOC/palliative care philosophy of comfort | Patient to be kept comfortable and pain-free; if that becomes difficult, refer to hospice for more wrap-around care – now will increase medications and refer to hospice | PCP, RN, SW |

“I want to be cremated” stated 5 years ago | Funeral plan | AM and her family have arrangement with XYZ Funeral Home. Copies of paperwork in chart at memory care, with daughter, and at PCP office | SW, housing director, daughter, PCP |

Daughter reports “My mom is suffering” | NPS: Mini-Suffering State Exam Score 7/10 | Problem solve as needed to support stable placement Provide caregiver assistance with developing interventions Continue to track MSSE, NPI-Q | MSW, RN |

Screaming and pushing | NPS: NPI-Q score 14/18 | Psychiatry collaborative consultation: recommends having daughter come at 3pm and lay down with her mother to see if “modeling how to rest” helps. Move AM away from the noise before it starts to increase around 3pm. Continue dementia-specific medications. Trial pain meds (low-dose opiate+bowel medications) while beginning behavioral interventions as she appears to be suffering greatly | PCP, consult with psychiatry |

AM able to walk, able to eat finger-food | Functional status | Continues as expected. Support by walking regularly with AM, and provide food in line with her preferences | Staff at MCU, daughter, activity dir |

Appears upset when medications are handed to her and when her CBG is checked | Medical: HTN DM | Discontinue all medications that are not being given for NPS Discontinue CBGs. Encourage fluids as elevated CBG can lead to dehydration | PCP, RN |

Daughter speaking for AM: MCU meets her mother’s needs | Living environment and safety | Continue MCU with added support from hospice staff | PCP, RN, MCU, hospice |

After review of the care plan, all team members sign:

AM _________ Date ______ Dtr A ________ Date ______

SW_________ Date _____ RN __________ Date ______

Aide ________ Date ______ OT__________ Date ______

PCP ______ Date _____ Housekeeper_________ Date _____

MCU Dir ________ Date ____ Act Dir ________ Date _____

Outstanding actions:

SW and PCP will make hospice referral and send the first and current person-centered care plans. Hospice to consult with AM, Daughter, MCU staff, and rest of team.Date of referral:________Comments/Additions from AM or Dtr A:________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Appendix B: Sample Care Plan Chapter 9

Background Information

Date of report: September 21, 2019 Client’s name or initials: BN

Date of birth: April 10, 1940

Reason for care plan update: Regular reassessments completed by all members of the team, now working on interdisciplinary care plan for BN.

Profile

BN is a 79-year-old woman who has lived in assisted living facility for the last 3 years and has mild MNCD. BN is able to have conversations. She enjoys talking, reading, and playing cards. She loses track of conversations at times and has limited recall. Notes don’t seem to help much.

-

Roman Catholic background. Attends mass on Sundays.

-

Librarian, loves to read, is in a book club at ALF.

-

Likes getting her hair done.

-

Loved to travel.

-

Husband was a civil servant.

-

No children. Niece lives in a distant state but calls BN once per month.

Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Q form: severity 2, caregiver distress 2

Anxiety 1/1, irritability 1/1

MSSE: 1/10 dialysis

BN’s perceptions: Things seem good right now. Lots of minor medical issues, but living here has been good for me. I have a whole new group of friends. The food is pretty good too.

Domain: End-of-life issues – now in a palliative care, functional focus track

BN perspective: “As long as I can keep going and enjoy time with friends, life is good.”

Other interdisciplinary team members – continue to support optimal quality of life. Life expectancy is less than 5 years. DNR is in place. If benefits of an intervention are less than risk over next 5 years, advise against them.

Participant perspective | Issues | Plan | Discipline |

|---|---|---|---|

I don’t want CPR; I saw that happen to my best friend, and it was awful | GOC: Focus on daily functioning palliative care philosophy | Encourage BN to be as active as possible; her “use it or lose it” attitude is lifelong | RN, ALF act dir, aides |

“I want to be cremated” stated 5 years ago | Funeral plan | Copies of paperwork in chart, with daughter and at PCP office | Housing director, PCP |

Denies suffering | Mini-Suffering State Exam Score 1/ 10 | Problem solve as needed to support functioning Provide caregiver education regarding end of life as needed | MSW, RN |

Some anxiety during dialysis | NPI-Q score 1/2 | Encourage listening to music and watching distracting movies during dialysis. Discuss when it may be time to stop due to not supporting a good quality of life, and document those discussions | Kidney team, PCP |

Domain: Cognition/functioning

BN perspective: “I lose track of some things, I need the staff help, life is good.”

Other interdisciplinary team members – Allen cognitive level 4.6 mild-moderate functional impairment. Strengths are ability to scan the environment and utilize objects if they are visible.

Participant perspective | Issues | Plan | Discipline |

|---|---|---|---|

I need reminders | Does not track dialysis days any longer, benefits from invitation to activities | Staff to come and get her for medical and dialysis appointments, invite to all activities, and keep track of her schedule for her | Aides, ALF RN, and manager to monitor |

Domain: Emotional/neuropsychiatric symptoms

BN perspective: I get nervous sometimes. I am not depressed. I enjoy being as active as I can.

Other interdisciplinary team members – the emotional impact of dialysis is emerging as an area to attend to closely. At some point, if it causes too much distress, will need to discuss stopping dialysis.

Domain: Medical

BN perspective: I can tolerate dialysis for now. Maybe not for too much longer. Otherwise, I don’t think I have medical problems.

Other interdisciplinary team members – continue much of current care. Frank conversation now with BN and her niece and the PCP about the future of stopping dialysis. Begin to plan for that. Send documentation of care plan to nephrologist and offer to have joint meeting with PCP, BN, and niece by phone with nephrologist.

Participant perspective | Issues | Plan | Discipline |

|---|---|---|---|

7 years ago, completed | Advanced directive | Participant named niece her primary healthcare power of attorney, she does not have an alternate | PCP |

“I get tired a lot” | End-stage renal disease on hemodialysis – secondary hyperparathyroidism and anemia CPAP at night History of low protein levels | Continue Sensipar and sevelamer Check labs prn Increase daily water intake Renal follow-up per schedule Lab draws/blood pressure checks left arm only Draw labs as ordered Hemodialysis three times a week Communicate with XXX Kidney Center to reschedule run when participant has missed run Make sure settings are correct every night and put away every morning Encourage compliance Replace respiratory care supplies per replacement schedule Renal diet: participant has been educated on renal diet guidelines Small portions of meals as she desires Nutrition supplement Weigh at ALF once a month, and send to PCP and nephrologist | PCP RN Care aide RN |

Domain: Living environment/safety

BN perspective: I really like living here. I have friends and enjoy activities.

Other interdisciplinary team members – At the current time, BN’s needs are being met well here. Continue to focus on maximizing ability to be as independent as possible.

Participant perspective | Issues | Plan | Discipline |

|---|---|---|---|

I love to read | Active in book club | Continue to encourage to read, especially well-loved books BN is familiar with | Activity director |

My eyes get tired when I read | Decreased visual acuity | Provide large print books and magnification device | Occupational therapist |

I sometimes forget when book club is; I would hate to miss it | Decreased short-term memory | Provide environmental cues to remind BN of schedule; large digit clock with alarm Reminds 10 minutes before group starts | Occupational therapist; activity director |

After review of the care plan, all team members sign:

BN _________ Date _______ Niece ________ Date _______

SW_________ Date _______RN __________ Date _______

Aide ________ Date ______ OT__________ Date ______

PCP _________ Date _____ Act Dir ________ Date _____

Housing Coordinator____________ Date _______Outstanding actions:Send copy of Person Centered Care Plan to Nephrologist officeDr. _____________ Date_________Comments/Additions from BN or Niece:________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Foidel, S.E., Nash, M.C., Rose, S.S. (2019). Person-Centered Care and Care Planning for Those with MNCD. In: Nash, M., Foidel, S. (eds) Neurocognitive Behavioral Disorders. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11268-4_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11268-4_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-11267-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-11268-4

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)