Abstract

Behavioral difficulties are widely recognized in children on the autism spectrum. Research has demonstrated that up to 80% of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) present with a range of comorbid difficulties, and up to 37% meet full diagnostic criteria for a disruptive behavior disorder. Left untreated, behavioral difficulties persist and can result in social isolation as well as exclusion in educational and community settings. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT), an evidence-based treatment for externalizing behavior disorders, has been empirically shown to ameliorate problem behaviors while increasing positive parenting behaviors and prosocial behaviors for children with ASD. The following case study further extends the literature by showing positive behavior and social outcomes for a 4-year-old boy with ASD at posttreatment and 3-month follow-up. In addition, through the lens of this individual case, the manuscript examines the general application of PCIT with the ASD population from a theoretical, therapeutic coaching, and case management perspective.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Autism spectrum disorder

- Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT)

- Externalizing behaviors

- Behavioral treatment

- Early childhood

1 Reason for Referral

“Mason” was a 4-year, 2-month-old boy with a history of premature birth, developmental delays, and concern for possible autism spectrum disorder (ASD). His pediatrician referred him to a university-based outpatient clinic for neuropsychological and behavioral evaluation and treatment . Mason’s pediatrician and parents reported concerns about language delays, periodic motor and verbal stereotyped behavior, emotional dysregulation, noncompliance, poor social interactions, repetitive behaviors, and inattention.

1.1 Family History

Mason’s parents were divorced. He lived primarily with his mother (who maintained primary custody) but often spent several days a week at his father’s home. While Mason did not have any siblings, he frequently spent time with his extended family (including cousins) from both his mother’s and father’s sides. Each of Mason’s parents was college-educated, his father was employed as a business analyst, and his mother was a homemaker. English was the only language spoken in both homes.

1.2 Medical and Developmental History

Mason was delivered after only a 30-week pregnancy. He was delivered vaginally following a prolonged labor weighing only 4 pounds. He was immediately treated in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) with a brief course of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) , a feeding tube, and phototherapy. Mason was kept in the NICU for approximately 8 weeks where he progressed favorably. He was described as a quiet and content infant who was easy to feed and slept well.

Although he was fairly easily soothed, Mason was described as being somewhat aloof, was delayed in developing a “social smile,” and would underreact when a caregiver entered his environment. In addition, he was delayed in meeting many of his milestones (e.g., first words at 16 months, walked at 18 months). He began receiving Early Intervention (EI) services as an infant and toddler including speech-language services and physical therapy. He had not received behaviorally based treatment at the time of referral. Other notable developmental concerns included his propensity for spinning toys, frequent arm flapping, unusual vocalizations, poor eye contact, and prolonged visual inspection of objects. Mason had a history of sensory sensitivities including touch, clothing texture, and food texture.

Medically, Mason was in good health. His parents reported no long-term NICU-related concerns. He had no history of seizure, head injury, or loss of consciousness. His vision and hearing were intact, and he was not prescribed medication. Regarding sleep, his mother was transitioning Mason from co-sleeping; Mason , however, typically co-slept with his father. When co-sleeping, he was able to sleep for 12 h at night; when alone, he woke often requesting his mother. Regarding eating behaviors, he had difficulty tolerating new foods as they were introduced to his diet and would often bring a food item to his mouth and immediately refuse to taste it.

1.3 Presenting Concerns

Mason’s parents described several concerns related to behavioral and emotional dysregulation, noncompliance, perseveration, and inattention. Generally, he had difficulty sustaining attention on tasks that were less preferred and following multistep instructions. Additionally, completing and persisting through tasks were challenging for him. Mason engaged in daily tantrum behaviors if a task was too challenging for him to complete, if he was told to do something that he did not want to do, or if there was an unexpected change in his routine. He had much difficulty transitioning between activities both at home and school. During tantrums, he would cry, yell, protest verbally, and occasionally be mildly aggressive toward his parents. He engaged in occasional hand-flapping behavior or vocal stereotypies (i.e., humming), namely during moments of overstimulation or task demands. His parents noted this behavior declined in frequency and intensity over the past 18 months.

Mason spoke in sentences with some articulation and verbal fluency difficulties. His parents reported that he had “more information inside than he is able to get out” and that he had difficulty engaging in back-and-forth conversations. Socially, he often had difficulty understanding social cues (e.g., when a child does not want to play with him) or joining a group of peers. For example, he may have approached a group of children who were playing together and roar at them pretending to be a dinosaur rather than asking to join. He did play appropriately with peers at times, but most of the play was focused around his interests (e.g., numbers, dinosaurs, cars). Occasionally he became physical with peers (e.g., pushing) to gain their attention, when he was unable to access a preferred item, or when a peer wanted to play with his preferred items. He also had difficulty understanding limits in social situations. For example, if he engaged in rough-housing with friends, he often extended the physical play further than his peers.

Mason’s parents reported that he initially adjusted well to preschool upon his enrollment at 3 years old. However, when transitioning back to his second year of preschool following summer break, he experienced significant behavioral difficulties. At this time, he engaged in frequent behavior outbursts (e.g., throwing self on ground, hitting peers, noncompliance) and required significant support and supervision within the classroom. When he presented to the clinic, these behaviors had somewhat improved due to the addition of a one-to-one aide; even still, teachers continued to have difficulty increasing Mason’s on-task behavior within the classroom. Teacher-report indicated that Mason had difficulty comprehending material in the absence of a visual representation. He also had difficulty retrieving vocabulary, engaging in conversation with peers, and expressing himself appropriately when in a heightened emotional state. Mason’s teacher reported that he often appeared to be “flooded” with language input, especially during transitions, sometimes resulting in intense stereotyped behaviors. When Mason was overwhelmed, he had more difficulty with language as well. It was discovered that he benefited from a “wait time ” (e.g., where he was given more time to comprehend what was going on around him before replying) and visual supports to assist him with accessing language and complying with directions.

1.4 History of Parenting Practices

Mason’s parents reported using a number of discipline methods, and did not feel that these methods had been fully effective in managing his behavior. They stated that some of the techniques would be effective but only for a short period of time. They also noted that expectations varied depending on which home Mason was staying. Parenting methods included removing Mason from a problematic situation, taking a walk around the neighborhood, sending him to his room, or giving him a cup of water “with magical powers” to help calm him down. Mason’s mother had attempted “timeout” in the past, which consisted of sitting him on a chair for approximately 2 min, or sending Mason to his room until he was able to calm down. His mother admitted she was inconsistent in her discipline methods, namely around timeout. Also, Mason began having more frequent toileting accidents around the same time she began implementing timeout, and she discontinued this strategy (toileting was not an issue at time of treatment). Mason’s father reported that because he spent less time with Mason, he had difficulty consistently following through with discipline strategies since he did not want to spend his limited time with Mason disciplining him. When Mason engaged in tantrum behavior, his father typically provided reassurance and ultimately allowed him to “have his way.” Overall, both parents agreed that their discipline practices had not helped to manage Mason’s behaviors effectively or taught him to cope with or manage his frustration.

2 Assessment

Mason underwent a full neuropsychological evaluation to examine his cognitive profile, confirm diagnostic presentation, and to assess his intervention needs. The evaluation consisted of standardized assessments, parent and teacher measures, and behavioral observations.

2.1 IQ

Mason was administered the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scales of Intelligence, Fourth Edition (WPPSI-IV; Wechsler, 2012) to assess his overall level of intellectual functioning. His intellectual abilities fell in the low average range overall; however , his performance reflected some variability across and within areas of his intellectual functioning indicating that his cognitive skills had developed unevenly. His fluid reasoning skills and verbal comprehension abilities were areas of strength and fell in the high average and average range. In contrast, his performance across visual spatial tasks was quite variable, and his overall performance fell in the low average range. Mason’s working memory abilities and processing speed skills were similarly low average, representing relative weaknesses in his profile. Overall, while his foundational cognitive abilities were intact (e.g., verbal and nonverbal reasoning), Mason had more difficulty understanding spatial relationships. He also demonstrated weaknesses in secondary cognitive skills including his ability to process information quickly and to hold information in his short-term memory to readily use it.

2.2 Vocabulary and Verbal Comprehension

Mason’s performance varied across measures of basic vocabulary and verbal comprehension. His performance was average on a measure of basic expressive language (Expressive Vocabulary Test—Second Edition; EVT-2; Williams, 2007) while his performance on a measure of basic receptive vocabulary fell in the low average range (Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test—Fourth Edition; PPVT-4; Dunn & Dunn, 2007). Similarly, his ability to follow directions and process complex language information fell in the borderline range (Differential Ability Scales—II; DAS-II; Verbal Comprehension subtest; Elliot, 2007). Although Mason’s ability to organize and retrieve words when provided semantic cues (i.e., verbal fluency) was average (NEPSY-II; Word Generation subtest; Korkman, Kirk, & Kemp, 2007), he had difficulty initiating his responses to this task but eventually provided many responses with encouragement. Overall, although Mason’s expressive language abilities were intact, he had more difficulty processing and understanding language.

2.3 Memory

Consistent with his low average working memory abilities, Mason’s recall of a short story fell in the low average range. When asked to recall story details, he became visibly overwhelmed and stated that the task was too difficult . When provided recognition cues, his performance improved to the average range (NEPSY-II; Narrative Memory subtest). On a verbal memory task, Mason was asked to repeat increasingly complex sentences (NEPSY-II; Sentence Repetition subtest). His performance fell in the borderline range, and he was able to repeat basic sentences with up to five words. Mason’s performance suggested that he had difficulty recalling and retrieving verbal information; he benefited from repetition and cues.

2.4 Autism Symptomatology

Mason was also administered the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2 ; Lord et al., 2013), Module 3, a semi-structured observation tool used to assess social functioning, communication, and interests using a series of “presses” (i.e., opportunities for a child or adolescent to demonstrate social competence). The ADOS-2 allows the examiner to observe behaviors that are helpful in evaluating the presence of ASD, identifying social communication and behavioral strengths and challenges, and capturing the severity of ASD-related symptoms.

2.4.1 Strengths

Mason demonstrated both areas of strength and impairment throughout the ADOS-2. Regarding areas of strength, he engaged in cooperative joint play with the examiner and demonstrated clear enjoyment during several interactions . He also directed a variety of facial expressions to the examiner. Mason engaged in interactive play with the examiner and demonstrated some emerging imaginative play skills.

2.4.2 Impairments

Despite these strengths , he also demonstrated several areas of impairment including stereotyped use of phrases and poorly modulated eye contact. He became fixated on a toy dinosaur during the assessment and had difficulty transitioning away from the toy, which he referred to frequently for the duration of the observation. Regarding nonverbal communication, he displayed few gestures to accompany his language . Although he responded appropriately to some of the examiner’s conversational bids, he had difficulty building upon them to engage in back-and-forth conversation. He was also observed to engage in occasional stereotyped motor mannerisms (e.g., arm flapping). Overall, his total score on the ADOS-2 was above the threshold for ASD.

2.5 General Functionality

Functionally, Mason’s parents and teachers reported significant levels of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity on the Behavior Assessment System for Children, 2nd Edition (BASC-2; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004). On the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function, Preschool Version (BRIEF-P), his parents and teacher reported significant difficulties on the Inhibition, Working Memory, and Emotional Control scales. Mason’s parents and teacher rated his overall social functioning to be in the severely impaired range on the Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition (SRS-2; Constantino & Gruber, 2012). Scores on the Sutter-Eyberg School Behavior Inventory (SESBI; Eyberg & Pincus, 1999) demonstrated general behavioral difficulties at school with compliance, attention, and peer relationships. Lastly, parent ratings on the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, 2nd Edition (Vineland-II; Sparrow, Cicchetti, & Balla, 2005) placed Mason’s adaptive functioning to be within the borderline range overall. Overall, Mason has difficulty with a variety of adaptive skills as well as behavioral and social functioning.

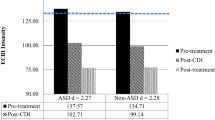

The Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI; Eyberg & Pincus, 1999) suggested that Mason was exhibiting a significant level of disruptive behavior (see Figs. 36.1 and 36.2). Specifically, Mason’s mother and father rated his behaviors as being clinically significant in intensity (Mother: Intensity = 165; Father: Intensity = 158) and both viewed these behaviors as significantly problematic (Mother: Problem = 14; Father: Problem = 15). Both phases of treatment began with a didactic parent teaching session followed by weekly coaching sessions. In addition, both parents were instructed to practice their skills on a daily basis. Mason’s parents were consistent in completing home practice with the exception of the first 2 weeks of treatment due to increased work demands for Mason’s father.

2.6 Behavior Observations

The Dyadic Parent-Child Coding System, Third Edition (DPICS; Eyberg, Nelson, Duke, & Boggs, 2004) was administered at pretreatment (and throughout therapy) to measure the content and quality of parent-child interactions . Frequency counts for parent verbalizations and child responses to commands were recorded during three 5-min standardized situations: child-directed play, parent-directed play, and clean up. The DPICS includes specific categories of parent verbalizations: positive parenting behaviors (e.g., behavior descriptions [BD], reflections [RF], labeled praises [LP]) and avoid skills (e.g., questions [QU], commands [CO], negative talk [NT]). At pretreatment, Mason’s parents demonstrated more avoid skills than positive parenting skills (see Figs. 36.3 and 36.4). Also, during DPICS assessment, Mason had difficulty transitioning away from playing with toy cars and dinosaurs, two of his highly preferred toys. At the start of treatment, it was decided to create a more natural environment where Mason would be more interested in play and to develop a paired association between his parents (using the skills) and his favorite items; therefore, Mason’s preferred toys were made available with those in the clinic as well as several he brought from home.

3 Case Conceptualization

Results of the evaluation reflected a number of strengths in Mason’s neurocognitive profile. His general intellectual functioning fell in the low average range, and his high average visual spatial abilities emerged as an area of strength. His verbal abilities were more variable however. Despite his history of language delay and communication difficulties, Mason’s expressive language skills were intact. Unfortunately, his receptive language abilities were below age-based expectations, suggesting that caregivers and teachers may have overestimated Mason’s ability to comprehend language at times.

In spite of his strengths, Mason also displayed some weaknesses in the areas of attention, executive functioning, and rote verbal memory. Across testing, he had more difficulty with auditory learning, consolidation, and retrieval of verbal information, suggesting that he benefited more from visual rather than verbal instruction. This deficit also likely impacted his ability to rapidly generate language and learned information. Parent- and teacher-report indicated that Mason struggled with language retrieval and was also easily overwhelmed and frustrated by large amounts of spoken language toward him. Although he performed well on testing, Mason was observed to withdraw and become upset during tasks that required language retrieval and rapid language generation. Lastly, Mason demonstrated difficulties with social awareness, social communication, and restricted and repetitive interests and behaviors. Parent and teacher ratings also reflected significant deficits in social and behavioral functioning across settings.

Based on information gathered in the intake, neuropsychological evaluation , and DPICS assessment, a certain level of Mason’s noncompliance was attributed to his rigidity and restricted interests. When Mason was engaged in these interests, it was often difficult to direct his attention elsewhere. These behaviors are common in the clinical presentation of children diagnosed with ASD and thus were considered to be accounted for under such a diagnosis (Volkmar et al., 2014).

Although Mason’s behavioral issues initially were centered on behavioral inflexibility (e.g., transitioning away from make-believe play with cars), the frequency and intensity of his defiance, tantrums, and emotional dysregulation, coupled with his parent’s reluctance or inability to implement consistent discipline strategies, appeared to have extended to a more general oppositional presentation across situations and contexts. Of note, it was clear that Mason’s behavior was also impacted by parental attention. For example, his disruptive behavior often increased at the outset of being ignored (i.e., extinction burst) and he would respond positively when provided with social reinforcement (e.g., therapist and parent praised Mason for allowing adult conversation to take place during intake session; he responded by hugging his parent and returning to play).

As such, it appeared Mason’s behavior served multiple functions ranging from escape/avoidance, self-reinforcement, and social reinforcement. Overall, the evaluation and test findings, combined with Mason’s developmental history and behavioral profile, were consistent with a diagnosis of ASD and oppositional defiant disorder. Research has demonstrated that up to 80% of children with ASD often present with a range of comorbid difficulties and up to 37% meet full diagnostic criteria for a disruptive behavior disorder (Kaat & Lecavalier, 2013; Simonoff et al., 2008).

3.1 Treatment Recommendations

In an effort to ameliorate Mason’s behavioral difficulties , Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT), an empirically based parent training program for young children exhibiting disruptive behaviors (Zisser & Eyberg, 2010), was recommended. Many efficacy studies utilizing PCIT with children with disruptive behavior disorders have demonstrated positive outcomes that include improvements in the parent-child relationship (a focus of the first phase of treatment, Child-Directed Interaction; CDI), and reductions of child disruptive behavior (through a structured discipline procedure—the focus of the second phase of treatment, Parent-Directed Interaction; PDI) and parental stress (Lieneman, Brabson, Highlander, Wallace, & McNeil, 2017). PCIT focuses on parent management strategies and the generalization of skills and strategies learned in-session to the home environment and in the community . Although PCIT was not originally developed for children with ASD, preliminary studies suggest that PCIT shows promise for decreasing disruptive behaviors and increasing prosocial behaviors with this population (Agazzi, Tan, & Tan, 2013; Masse, McNeil, Wagner, & Chorney, 2007; Masse, McNeil, Wagner, & Quetsch, 2016; Solomon, Ono, Timmer, & Goodlin-Jones, 2008). Additionally, parents of children with ASD have benefited from PCIT, showing reductions in parent perceptions of child problem behaviors as well as decreases in stress related to parent-child interactions (Agazzi, Tan, Ogg, Armstrong, & Kirby, 2017; Solomon et al., 2008).

4 Course of Treatment

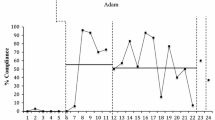

Mason’s parents both identified the primary treatment goal as reducing Mason’s noncompliance and problem behaviors across settings. This was especially important as behavioral difficulties and problem behaviors, although common in children with ASD , can result in social isolation as well as exclusion in educational and community settings (Horner, Carr, Strain, Todd, & Reed, 2002). Treatment involved both parents and consisted of 20 treatment sessions conducted over approximately 5 months (10 CDI sessions, 10 PDI sessions). Mason’s mother met CDI mastery in CDI Coach 8 while his father met mastery in CDI Coach 9; both parents met mastery for PDI skills in PDI Coach 8. Of note, despite meeting quantitative mastery just prior to CDI session 9, CDI coaching was extended to practice differential attention skills with Mason and his parents. Given that a large amount of Mason’s behavior was reinforced by social attention, having Mason’s parents use differential attention effectively was high priority before moving on to PDI.

4.1 CDI

At the outset of CDI , Mason’s parents were coached to provide a great deal of attention to Mason’s activity with the restricted set of toys. As his parents began to utilize more CDI skills (Praise, Reflection, Imitation, Describe, Enjoy; PRIDE skills), they began to incorporate non-preferred toys into the playtime. For example, Mason’s parents were instructed to build a road and garage made of Lincoln Logs while saying, “I am going to build a road for your cars and a garage as a place for them to sleep.” The road was built strategically so that it was required to interact with Mason’s toys (“You’re making your car go down the road! Nice job of gently moving your car into the garage! I like when our toys play together”). Although Mason seemed somewhat disinterested in his parents’ play at first, coaching focused on praising behavioral approximations (e.g., looking over toward his mother, touching the Lincoln Logs or Legos) until he eventually joined in more reciprocal play. Over time, whenever Mason began to incorporate car or dinosaur themes into the play (“This Lego tower is like a growling dinosaur”) his caregivers would proceed with a “one-and-done” approach; this approach involved attending to Mason’s behavior once (“A growling dinosaur”; [RF]) and then redirect with neutral talk (“I am going to put a window on the tower”; see Chap. 24 for more information on this technique).

During the initial CDI sessions , Mason’s mother began to quickly incorporate PRIDE skills into her playtime with Mason, but also engaged in a significant amount of neutral talk at the expense of allowing Mason to generate verbalizations (one of his areas of relative weakness). Although she frequently attempted to engage Mason in play, he initially appeared to prefer playing alone. In contrast, Mason’s father engaged in very little speech and rarely imitated Mason’s play behaviors (typically sitting to the side and watching Mason play). After observing this pattern during the first two CDI Coach sessions, Mason’s mother was coached to decrease vocalizations (Therapist: “Go ahead and reflect that and then let’s just listen and see what he’s going to say next”). To prevent Mason from becoming overwhelmed by too much language, his father was encouraged to increase his rate of vocalizations while engaging in imitative play.

4.2 PDI

During the PDI phase, Mason required five clinic-based timeouts and six home-based timeouts. The initial timeout took place in PDI Coach 1 when Mason was instructed to transition away from playing with cars to a less-preferred toy. The timeout lasted approximately 45 min requiring several chair-to-room iterations. During the timeout, Mason was initially aggressive with his parents (e.g., punching, pulling away) on the way to the chair, namely when coming from the timeout room. As such, the following adaptations were made to protect the safety of Mason and his parents.

4.3 Adaptations

4.3.1 Social Story

In an effort to incorporate Mason’s strengths and preference with visual learning, Mason and his parents developed a Social Story (Gray & Garand, 2016) with each page displaying a picture and short statement demonstrating all the critical elements of the timeout procedure. This method was introduced (prior to moving on to PDI) to allow Mason time to form an understanding of the structured discipline procedure. Mason’s story emphasized all the positive benefits of listening to his parents as well as the notion that if a timeout would be needed, it could be brief (if he stayed on the chair), didn’t “have to ruin his day,” and would always end with special time with his parents. Each day between the PDI Teach session and PDI Coach 1 (and thereafter during the acute PDI training phase), Mason and his parents read the social story. Given his deficits, repetition of the story was important and provided more confidence that Mason had an understanding of the procedure without solely relying on the more verbal-laden timeout explanation that occurs during PDI Coach 1. Of note, teaching of the timeout still occurred with Mason at the outset (using Mr. Dinosaur) of PDI Coach 1 but included more emphasis on visual demonstration.

4.3.2 Additional Prompt Before Returning to Timeout Chair

Before attempting to get Mason from the room to the chair, his parents were coached to say, “Since you are being quiet in the room, are you ready to sit on the timeout chair?” If Mason gave any physical or verbal indication of refusal, the 1 min +5 s of quiet period was restarted. This modification was needed only in early PDI sessions due to potential safety issues. Thereafter, Mason required the timeout room less and, if needed, he was able to self-regulate more quickly.

Following the PDI Coach 1 timeout, as a way to capture behavioral momentum and for Mason to experience positive attention for more immediate listening, Mason was administered and complied with four consecutive commands of varying difficulties. PDI Coach 2 contained two timeouts with the first being 10 min in length and the second 5 min in length. The final two timeouts came in later PDI sessions and were both short-lived (i.e., likely a demonstration of spontaneous recovery of behavior).

4.3.3 Social Story for House Rules

Although active ignoring was effective in managing many of Mason’s behaviors, he continued to be mildly aggressive toward his parents on occasion at home. As such, both parents identified this behavior as a target for house rules. During the explanation of the house rule, a Social Story was created for Mason illustrating a boy going to the timeout chair for hitting his parents and friends. Similar to introducing PDI, to ensure Mason understood the house rule, his parents spent 1 week identifying and labeling the hitting behavior and reviewing the Social Story daily. The following week, the house rule of “no hitting” was introduced within both homes. While Mason initially received approximately two timeouts per week, this number decreased to approximately one per week after 3 weeks.

4.3.4 Public Behavior Precautions

Next, PDI sessions focused on public behavior. Mason’s parents worked closely with the PCIT clinicians to carefully choose public outing locations for both in-session and home practice that would reduce the likelihood of Mason becoming overstimulated by noise, light, or other children. Mason’s mother initially practiced at an outdoor market during an off-peak time, and his father took Mason to a local park during school hours—when it was less busy. While the PCIT therapists would have typically conducted an in-session practice at a local children’s museum or library activity center, these locations were deemed as being too stimulating (e.g., having too many children, too much fluorescent lighting). Instead, Mason’s parents gave commands within a local coffee shop (during off-peak times) with a small play area to increase Mason’s likelihood of compliance. Once consistent compliance was attained in these settings, the locations were slowly expanded to places his caregivers would more regularly visit. Throughout this learning phase and thereafter, Mason’s caregivers remained cognizant about the impact of Mason’s environment on his behavior.

4.4 Posttreatment and Follow-Up

Table 36.1 displays parent and teacher-rated assessments at pretreatment, posttreatment, and 3-month follow-up while Figs. 36.1, 36.2, 36.3 and 36.4 display ECBI scores and positive parenting skills for each parent. At posttreatment, both parent ECBI scores were well below the clinical cutoff (Mother: Intensity = 105, Problem = 8; Father: Intensity = 100, Problem = 7), and parenting skills remained above mastery levels.

4.4.1 Mason’s Father

Mason’s father reported that prior to PCIT, he was unsure of how to play with Mason. Often, when he would attempt to engage in play, Mason would become fixated on a preferred toy, engage in self-stimulatory behavior , or ignore his father. This eventually led his father to reduce his efforts to play with Mason, likely impacting the quality of the relationship. Through PCIT, Mason’s father learned how to utilize positive communicative skills to increase Mason’s prosocial behavior (including increasing his ability to engage in conversation surrounding play), and to redirect Mason’s behavior when he became fixated on toys or other activities.

4.4.2 Mason’s Mother

Although Mason’s mother was able to engage him in play more easily at pretreatment, she reported that she was unaware of how much her language (e.g., word choice, rate of speech) impacted Mason’s behavior. Through PCIT, she learned how to use her language more effectively to increase Mason’s receptive vocabulary and expressive language, help him build language around emotions, and provide structure by giving commands in a predictable and measurable manner. Most importantly, she felt confident in knowing that both she and Mason’s father were consistent in their play strategies, expectations, and discipline procedures across homes.

4.4.3 Mason

Prior to treatment, Mason had difficulty sustaining attention on less-preferred tasks, would often not complete tasks that were challenging for him, and had trouble navigating transitions. Following PCIT, these behaviors improved considerably. Mason persisted more during times of frustration, and his reflexive “no” response to requests diminished. In doing so, his ability to make transitions improved, he appeared to develop more self-efficacy and confidence with a broader range of tasks, and he was able to expand his play and social repertoire; he was thus more willing to approach unfamiliar tasks and experience subsequent positive feedback. Interestingly, Mason’s amount of expressive language and verbal fluency also improved over the course of PCIT therefore supporting theoretical notions that PCIT facilitates language development (Tempel, Wagner, & McNeil, 2009) and extending prior research demonstrating similar results (Ginn, Clionsky, Eyberg, Warner-Metzger, & Abner, 2015; Masse et al., 2016). Lastly, Mason exhibited less vocal and self-stimulatory behavior at the completion of treatment, likely as a function of being less overwhelmed and overstimulated by parental language and demands.

4.4.4 Follow-Up

At 3-month follow-up, Mason’s parents showed some regression in their level of PRIDE skill use compared to posttreatment . However, their skills remained at a high level compared to pretreatment assessments. Interestingly, both parents reported higher ECBI Intensity scores at follow-up, yet Problem scores remained below clinically significant levels; this suggests that although Mason’s disruptive behavior may have intensified after treatment, both parents felt that they were able to effectively manage these behaviors. Given the chronic nature of ASD and likelihood that some externalizing behaviors will persist, parental perception of ability to manage difficult behaviors is critical in the long-term maintenance of behavior.

In general, Mason’s parents reported more improved scores across assessments in comparison to his teachers showing that some of Mason’s improved behaviors may not have generalized. The exception to the trend was aggressive behaviors, which also reduced in the school setting. Both his parents and teachers did see a slight improvement in social relatedness (e.g., SRS-2) namely in the area of social communication. Specifically, both raters noticed some improvement on items involving turn-taking, making friends, and relating to peers.

Lastly, Mason’s scores on a receptive language measure improved over the course of treatment. This score may be a reflection of his behavior disallowing him from performing at his optimal level. It is possible that his improvement in behavior following treatment resulted in a more valid assessment of his capabilities. Alternatively, Mason’s improved behavior may have increased parent-child communication placing him in a position to enhance his vocabulary skill set over the course of several months.

5 Theoretical Considerations

5.1 Social Reinforcement

A crucial consideration with conducting PCIT with the ASD population is determining whether social attention positively reinforces neutral or positive behavior while the removal of social attention diminishes or extinguishes unwanted behavior. Essentially, the effectiveness of PCIT is predicated upon this notion. An advantage of PCIT coaching is that it serves as a continuous functional analysis of behavior to assess whether social attention indeed impacts behavior. Clinical successes and research findings have demonstrated that PCIT does affect positive change mediated by social attention for children on the spectrum. Determining the rate of the impact or the particular subset of children who respond more favorably to PCIT is an area in further need of empirical attention.

For Mason, the impact of social attention on both positive and negative behavior was evident during the initial evaluation phase, so there was some expectation that he would respond favorably to PCIT. His parents’ skill acquisition initially progressed slowly but rapidly increased after several sessions. Of note, his parents were more inconsistent with home practice over the first 2 weeks of CDI likely impacting the rate of PRIDE skill acquisition and limiting Mason’s exposure to the skills. Once the skills started to be delivered at higher frequencies, the value of differential reinforcement increased and had a strong bearing on his behavior. Since differential reinforcement was a crucial part of therapy for Mason, an extra CDI coach session was dedicated to practicing this skill . During PDI, functional assessment revealed that Mason’s noncompliance often served two functions: self-stimulation and avoidance of less-preferred tasks or activities. As noted below, differential attention did not entirely eradicate self-stimulatory behavior , but did reduce the behaviors drastically. For behaviors with an avoidance function, timeout proved to be very effective at quickly increasing his initial compliance rate and demonstrating that removal from positive attention improved Mason’s behavior.

6 Coaching Considerations

Conducting PCIT with children on the autism spectrum can be different than the traditional course of therapy. In fact, PCIT for ASD is sometimes referred to as “snowflake ” PCIT as each case is different than the next. This requires some clinical agility to ensure that coaching is tailored to meet the needs of the family and child. It also requires practice, keen observation skills, and the ability to connect coaching statements with overarching treatment goals. For example, instead of, “Great labeled praise,” a coach could say, “Nice labeled praise, and I notice that he’s sitting closer to you now and making great eye contact.” Also, “It’s good to observe you ignore his self-stimulation so we can see how it influences his behavior.” “Have you noticed he’s no longer drawing the same number and is allowing you to draw on his picture?” By doing this, parents may be more motivated to continue with PCIT. This is especially important given that research suggests more CDI sessions are needed for children on the autism spectrum (Masse et al., 2016).

6.1 Imitation and Neutral Talk

Imitation and neutral talk were emphasized during the course of PCIT given their ability to be used as “entry skills” into the play. Specifically, imitation allowed Mason’s parents to play with Mason while still keeping him in the lead. Strategic neutral talk was used as a skill to increase verbalizations with Mason in early CDI sessions. Each parent was coached to relate the play to Mason’s favorite topics: cars and dinosaurs. For example, a parent would say, “This red block reminds me of that Mustang we saw on the highway,” or “The giraffe looks sort of like a Brontosaurus.” These statements were bids for communication and did not require a response. In short time, Mason engaged his parents in these topics and was quickly praised (e.g., “Thanks for talking with me, you’re right, the giraffe does look more like a Brachiosaurus”). Eventually, once momentum was established, Mason’s parents began to slightly veer from the fixed interest to expand Mason’s conversational repertoire (e.g., “That is a ‘67 Mustang. A mustang is also another name for a horse”; <Expansion>).

Building comfort with silence was also an important part of treatment. Mason’s parents were encouraged to allow silence following an ignore or a command sequence. This silence gave Mason time to behaviorally return to baseline before continuing play. In addition, this also prevented him from further escalating or engaging in self-stimulatory behavior due to being overstimulated. At the outset of treatment, Mason’s mother had the tendency to administer statements in “rapid fire” succession . As such, she was coached to pace her neutral statements more evenly. By slowing down the verbal tempo, Mason’s stimulation levels were more homeostatic, enabling a richer parent-child interaction. Additionally, Mason’s parents eventually incorporated neutral talk around emotions. Because Mason tended to have difficulty expressing himself when experiencing strong emotions, his parents began to label and praise obvious emotion whenever possible (e.g., “I see that you are smiling. That shows me that you are happy”). Further, Mason’s parents were also instructed to model emotion (e.g., block tower falls over and parent states, “That’s frustrating, I’m making my frustrated face,” or “It makes me happy to see you happy, so I am smiling too”).

6.2 Self-Stimulatory Behavior

Mason’s motor and verbal self-stimulatory behavior was targeted throughout PCIT. For verbal behavior (e.g., buzzing lips, humming), his parents were instructed to ignore and praise positive opposite behaviors (e.g., engaging in conversation with them, playing quietly). Mason also engaged in periodic motor stereotypies (e.g., arm flapping). Early on in PDI, it was determined that the function of the behavior was, at times, self-stimulatory , as he did not appear to engage in the behavior to avoid following commands or engaging in less-preferred activities. Similarly, if the behavior was not interfering with the situation, his parents were again coached to engage in active ignoring and to praise Mason for engaging in positive opposite behaviors (e.g., sitting nicely, standing calmly).

For behaviors that interfered, served as an escape function to demands, or were used as transition avoidance, clinicians instructed parents to give incompatible commands during PDI. Initially, his parents instructed him to engage in an opposite behavior (e.g., pick up a toy, stack a block) or that encouraged him to reengage in play with his parents (e.g., sit next to parent, place cow in the parent’s barnyard set). Although these strategies did not appear to decrease the overall frequency of Mason’s stereotyped behavior , they did decrease the duration of the behavior. Moreover, they provided a technique for his parents to redirect the behavior when demands were placed on Mason, thus disallowing escape or avoidance. As such, his parents reported feeling more confident in their ability to manage his stimulatory behavior at home and in the community.

6.3 Restricted Interests

In terms of incorporating restricted interests into the play, Mason was allowed to bring cars and dinosaurs into the first CDI sessions. Including such toys is a case-specific clinical decision that should be weighed carefully. Ultimately, the long-term goal was for Mason to have a broad range of interests. However, excluding these toys can oftentimes create a non-naturalistic environment that may impact a child’s initial adjustment to the treatment. As mentioned previously, parents can integrate other toys with preferred items as a way to expand play repertoire. In addition, Mason often created structured “rules” with his toys resulting in a patterned, ritualistic manner of play (e.g., only the red car can cross the bridge, a required count of three cars prior to pushing them down the track). Although Mason’s parents were instructed to follow his lead and play along according to his rules, on occasion, his parents were told to verbally narrate their own imitative play that purposely broke his rules (e.g., allowing different colored cars to cross the parent’s bridge, not counting cars before starting them down the track). Whenever a rule was “broken” in the context of Mason’s play (e.g., a parent drives a blue car across Mason’s bridge), his parents were then required to notice and praise the behavior with a socially based rationale (“Thanks for letting me use my car on your bridge. That’s being flexible and friendly and I know children at school would love to play that way too”).

Mason’s restricted interest in numbers also became apparent throughout PCIT, and created distress for both parents. When out in public, Mason frequently became preoccupied with numbers on clocks, aisles, or items within a store, and his parents would spend long periods of time attempting to pull him away without “creating a scene.” When provided with paper and crayons during special playtime, Mason would begin writing numbers repeatedly in different orders. Throughout CDI, Mason’s parents utilized a “one-and-done” approach where they worked to describe or reflect, and then quickly redirected to a different toy.

During PDI, his parents learned how to join his activity, describe it once, and then use commands to decrease his fixed behavior surrounding the activity. Initially, in an effort to develop behavioral momentum, commands focused on stimuli within his fixed interest (e.g., “Please write the number 3,” “Please draw a number on my piece of paper”). Once Mason demonstrated compliance to this level of instruction, commands surrounding drawing and writing were intensified (e.g., “Please draw a circle around the number,” “Please make the number 1 into a stick figure person”). Efforts were made to provide an adaptive replacement behavior by purchasing basic math workbooks to encourage Mason to use numbers and letters in an appropriate manner (e.g., not writing long lists of numbers on paper in a random fashion). Both parents reported that prior to beginning PCIT, it was almost impossible to gain Mason’s attention when he became fixated on a number, toy, or other activity and that the PDI strategies expanded his play repertoire.

7 Case Management Considerations

7.1 Managing Stressors

Conducting PCIT with divorced parents does not always progress as seamlessly as this case. A typical concern is that PCIT skills may not be consistent across contexts, which Mason’s mother reported at the outset of therapy (of course there are other concerns such as over-involvement of children in the parent’s relationship or lack of involvement of one parent in therapy, though these issues are beyond the scope of this case study). As such, much of PCIT focused on helping Mason’s parents become consistent regarding parenting and discipline strategies. Since Mason’s parents were committed to treatment and shared about an even amount of time with Mason, it was decided that PDI would be withheld until both parents reached mastery. Although the environment in each home was different, both parents acknowledged that consistency would be important in managing Mason’s expectations across settings. As many of the problem behaviors occurred when he did not get his way or when there was an unexpected change in routine, helping to make daily routines (e.g., visual schedules, Social Stories) as well as discipline practices consistent across home settings was important to both parents. Additionally, they recognized the importance of helping Mason cope with frustration or anxiety in unknown or unexpected situations (e.g., providing a rationale for the change, engaging in active ignoring, following the timeout procedure for escalating behaviors or house rules). Following PCIT, both parents reported feeling a great sense of relief in knowing that they had gained skills to co-parent more consistently going forward as well as gaining language (e.g., PRIDE skills) to increase Mason’s rate of positive and prosocial behaviors.

Related to parental divorce is parental stress. Research shows that parents with children on the autism spectrum experience a significantly greater level of stress in comparison to non-ASD children or even children with other disabilities (Hayes & Watson, 2013). Both of Mason’s parents experienced a large amount of stress as a result of Mason’s diagnosis, their divorce, and from the father’s demanding job and schedule changes. As such, clinicians were careful to monitor parental mental health and dedicate more time in the check-in/out to process stressors. Clinicians often met separately with parents as to preclude potential conflict and to respect privacy. This made session timing difficult at times and would require some creativity (e.g., check-in via phone, dedicated time to each parent at beginning/end of sessions).

During the course of therapy, Mason’s mother reported very high levels of stress and behaviors consistent with depression. As such, clinicians provided support and psychoeducation (not treatment) focused on the mental health impact of parenting children with ASD and facilitated a referral for individual therapy. Fortunately, much of the stress focused on Mason ameliorated over the course of PCIT as parents learned ways to better manage Mason’s behavior. Both parents reported by the end of PCIT that they had a “new lease on life,” felt like time spent with Mason was less contentious, and were able to have more meaningful experiences with Mason.

7.2 Incorporating Neuropsychological Findings

In this case, findings from neuropsychological testing helped to inform treatment decisions. Specifically, Mason’s neurocognitive profile was an important consideration throughout the course of treatment. As Mason was quickly overwhelmed with verbal input, his parents were encouraged to pace their use of skills accordingly and to monitor for cues that suggested Mason needed a neurological “break.” Also, rather than relying on his weaker verbal learning abilities, visuals were incorporated during teaching moments. Mason’s introduction to the timeout procedure relied on multi-modal instruction to maximize his learning. A timeout visual was also incorporated throughout PDI to remind Mason of the timeout procedures (e.g., when parents gave timeout warning they provided a visual of the timeout chair) and a Social Story was used to assist with teaching house rules and public behavior.

Based on testing results, Mason’s treatment also incorporated a more developmentally appropriate command sequence. Specifically, Mason’s caregivers first modeled the command-compliance sequence prior to administering contingency-based commands. This way, the procedure included a vicarious learning element to ensure Mason understood the details of PDI. Due to his weaker working memory skills, Mason’s parents provided simple, concrete commands throughout PDI. Due to his slower processing speed, consideration was also given to Mason’s potential need for slightly more than 5 s to process commands. Although the level of testing in this case is not always available in outpatient clinical settings, this report highlights the importance of utilizing assessment data during PCIT implementation to ensure the treatment is assessment driven and developmentally appropriate. Oftentimes, children with ASD present to PCIT with prior testing reports. It’s encouraged that clinicians read these reports with an eye toward PCIT treatment planning ; this can help inform their clinical approach based on the varied sets of strengths and weakness profiles of children on the spectrum.

7.3 School/Teacher Involvement

The involvement of Mason’s teacher consisted of completing checklists and providing classroom-based observations. As noted in the teacher report , Mason’s behaviors in the classroom were not positively impacted to the extent they were in the home environment. Although some research suggests PCIT outcomes generalize to the classroom setting (McNeil, Eyberg, Eisenstadt, Newcomb, & Funderburk, 1991), Mason’s teachers certainly would have benefited from more on-site coaching to help manage his behaviors. Also, it was unclear as to whether the school would be able to support Mason’s one-on-one aide going forward, so school-based assistance would have been a beneficial complement to PCIT. With Teacher-Child Interaction Training programs beginning to proliferate (Fernandez, Gold, Hirsch, & Miller, 2015), it would be interesting to determine the level of impact this intervention could have with children on the autism spectrum.

8 Conclusion

Conducting PCIT with children on the autism spectrum is both challenging and rewarding. Each case (and sometimes each session) brings along an element of uncertainty, different questions, and various challenges that require clinical flexibility grounded in sound behavioral theory. Moreover, therapeutic “success” is measured in different ways. Overall, Mason benefited tremendously from PCIT across both behavioral and social domains, and treatment gains maintained at 3-month follow-up. Mason’s parents reported less parental stress, developed confidence in their overall parenting approach to manage a range of behaviors, and concurrently strengthened their relationship with Mason. This case study serves as additional empirical evidence that children with ASD and co-occurring behavioral difficulties benefit from PCIT. Clinically, details of the case hopefully serve to guide PCIT clinicians as they continue work with the ASD population.

References

Agazzi, H., Tan, R., Ogg, J., Armstrong, K., & Kirby, S. (2017). Does Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) reduce maternal stress, anxiety, and depression among mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Child and Family Behavior Therapy, 39(4), 283–303.

Agazzi, H., Tan, R., & Tan, S. Y. (2013). A case study of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for the treatment of autism spectrum disorder. Clinical Case Studies, 12(6), 428–442.

Constantino, J. N., & Gruber, C. P. (2012). The Social Responsiveness Scale—Second Edition. Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, D. M. (2007). Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test—Fourth Edition. Mineapolis, MN: Pearson Assessments.

Elliott, C. D. (2007). Differential ability scales—II: Manual. Bloomington, MN: Pearson.

Eyberg, S. M., Nelson, M. M., Duke, M., & Boggs, S. R. (2004). Manual for the Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System—Third Edition. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida.

Eyberg, S. M., & Pincus, D. (1999). Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory and Sutter-Eyberg Student Behavior Inventory: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Fernandez, M., Gold, D., Hirsch, E., & Miller, S. (2015). From the clinics to the classrooms: A review of Teacher-Child Interaction Training in primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention settings. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(2), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.01.004

Ginn, N. C., Clionsky, L. N., Eyberg, S. M., Warner-Metzger, C., & Abner, J. P. (2015). Child-directed interaction training for young children with autism spectrum disorders: Parent and child outcomes. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46(1), 1–9.

Gray, C. A., Garand, J. D. (2016). Social stories: Improving responses of students with autism with accurate social information. Focus on Autistic Behavior, 8(1), 1–10.

Hayes, S. A., & Watson, S. L. (2013). The impact of parenting stress: A meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 629–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1604

Horner, R. H., Carr, E. G., Strain, P. S., Todd, A. W., & Reed, H. J. (2002). Problem behavior interventions for young children with autism: A research synthesis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32(5), 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020593922901

Kaat, A. J., & Lecavalier, L. (2013). Disruptive behavior disorders in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: A review of the prevalence, presentation, and treatment. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7, 1579–1594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2013.08.012

Korkman, M., Kirk, U., & Kemp, S. (2007). NEPSY—Second Edition (NEPSY-II). San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment.

Lieneman, C. C., Brabson, L. A., Highlander, A., Wallace, N. M., & McNeil, C. B. (2017). Parent-Child Interaction Therapy: Current perspectives. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 10, 239–256. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxylocal.library.nova.edu/10.2147/PRBM.S91200

Lord, C., Rutter, M., Dilavore, P. C., Risi, S., Gotham, K., & Bishop, S. L. (2013). Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition. Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Masse, J. J., McNeil, C. B., Wagner, S. M., & Chorney, D. B. (2007). Parent-Child Interaction Therapy and high functioning autism: A conceptual overview. Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention, 4(4), 714–735.

Masse, J. J., Mcneil, C. B., Wagner, S., & Quetsch, L. B. (2016). Examining the efficacy of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy with children on the autism spectrum. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(8), 2508–2525.

McNeil, C. B., Eyberg, S., Eisenstadt, T. H., Newcomb, K., & Funderburk, B. (1991). Parent–Child Interaction Therapy with behavior problem children: Generalization of treatment effects to the school setting. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 20, 140–151.

Reynolds, C. R., & Kamphaus, R. W. (2004). Behavior Assessment System for Children (2nd ed.). Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Charman, T., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., & Baird, G. (2008). Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 921–929.

Solomon, M., Ono, M., Timmer, S., & Goodlin-Jones, B. (2008). The effectiveness of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for families of children on the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1767–1776.

Sparrow, S. S., Cicchetti, V. D., & Balla, A. D. (2005). Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales—Second Edition. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Tempel, A. B., Wagner, S. M., & McNeil, C. B. (2009). Parent-Child Interaction Therapy and language facilitation: The role of parent-training on language development. The Journal of Speech and Language Pathology—Applied Behavior Analysis, 3(2-3), 216–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0100241

Volkmar, F., Siegel, M., Woodbury-Smith, M., King, B., McCracken, J., & State, M. (2014). Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. & the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Committee on Quality Issues, 53(2), 237–257.

Wechsler, D. (2012). Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence—Fourth Edition. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

Williams, K. T. (2007). Expressive Vocabulary Test, Second Edition. Circle Pines, MN: AGS Publishing.

Zisser, A., & Eyberg, S. M. (2010). Parent-Child Interaction Therapy and the treatment of disruptive behavior disorders. In J. R. Weisz & A. E. Kazdin (Eds.), Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents (2nd ed., pp. 179–193). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Elizabeth Wolock for her contributions to the manuscript, Mason and his family for their dedication to one another, and all the PCIT clinicians who continue to work effortlessly with children on the autism spectrum and their families.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rowley, A.M., Masse, J.J. (2018). PCIT and Autism: A Case Study. In: McNeil, C., Quetsch, L., Anderson, C. (eds) Handbook of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for Children on the Autism Spectrum. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03213-5_36

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03213-5_36

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-03212-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-03213-5

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)