Abstract

I will discuss the implications of identity theorizing to the design of curricula. I suggest understanding identity negotiations as the main processes of learning and human development. The nature of this process is narrative allowing the construction of personally relevant meanings. Autobiographical narratives become identity stories working as anchors to place one’s life course in time and contexts. These narratives comprise the capital for identity repositioning as a resource in future life contexts. I will argue that identity narratives are important both from ontological (what is) and epistemological (meanings) points of view for human learning. I will suggest curriculum as a space for narrative negotiations from autobiographical, social and cultural perspectives. These negotiations aim at a reconstruction of meanings and continuous development of identities as the main outcomes of education.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

We human beings are born without identities or any kind of conceptions about what there is around us. Who we are, where we are, and what is around us has to be learned along the course of life. Learning is thus the key process affecting our understanding of the world and also of ourselves. In this chapter, I will describe learning as a continuous holistic process in which the person constructs meanings discursively, through negotiations with and between him/herself, other people and different life contexts. The concept of identity, and particularly identitypositioning, is helpful in understanding the nature of this process. It may also help in understanding the difficulties in complex conversations of internationalizingcurriculum studies.

Identity is an easy concept as used in everyday language. However, there is not a single definition for the concept in research and theoretical literature (e.g. Brubaker and Cooper 2000). The literature on identity can be divided roughly into philosophical, sociological, and psychological perspectives (see Alcoff and Mendieta 2003; Bruner 1986; Côté and Levine 2002; Giddens 1991; Erikson 1959; Marcia 1994; McAdams et al. 2006; Leary and Tangney 2011; Ricoeur 1987, 1991; Taylor 1989). In psychological discourse on identity, the concept is usually used synonymously with the concept of self. The ontology of identity in psychological discourse refers to the development of self or personal identity as a characteristic developing from childhood to adult age. From an empirical standpoint, identity is a research question. For instance, researchers may ask what kind of identities people have and how those identities develop during the life course. Sociological literature on identity uses the concept in the context of membership to social institutes and structures. This work has a long history from Mead’s (1934) seminal book Mind, Self and Society to later developments of Giddens (1991) and Weigert et al. (1986) to mention just a few.

Philosophical literature on self and identity has been crucial for understanding the origins and nature of identity. I only refer to Taylor’s (1989) and Ricoeur’s (1991) contributions to understanding the genesis of modern identity. Taylor relates this discussion to moral issues, and Ricoeur theorizes the narrative nature of identity.

Taking a sociological tack, Côté (2006) has divided literature on identity into eight categories depending on the epistemology (objectivist, subjectivist) and whether the focus is individual or social. Both the individual and social focus are divided into two approaches, namely status quo and critical/contextual. The life historic and narrative approach I am referring to in this article belongs in Côté’s categorization to subjectivist and individual focus (status quo).

In the context of schooleducation, identity has been long neglected (Lannegrand-Willems and Bosma 2006; Limberg et al. 2008). For instance, in the 2004 Finnish National Curriculum Framework for school-based curricula, identity has been mentioned only a few times in the context of a need to enhance students’ cultural identity (Finnish National Agency 2004).

Whether or not the information age has changed our basic assumptions concerning education can be disputed. Nevertheless, it is evident that in the age of modernity, society has provided a more collective identity and moral basis through different institutions, traditions and faiths. Current ideological changes call for questioning the formerly taken-for-granted knowledge and moral bases. This applies at least to Western societies in which the so-called postmodern order has changed the role of institutions. Such changes in social conditions (i.e. away from collectivity) bring a movement to increasing individuality and demand for individual identities. These processes have also changed the role of education and teachers (Ropo and Värri 2003, p. 305). The societal, cultural and environmental discourses, to mention just a few, make teachers’ roles more complicated than ever as facilitators of students’ identitynegotiations. What should teachers learn in teacher education and what positions should they take in respect to many controversial global, societal or moral conversations? The role of subject-specific expertise cannot be denied as the basis for being a teacher. Like we wrote over ten years ago:

Modern teachership, the present teacher education, and the present school institution have been constructed on the basis of scientific education and curriculum design (see Hargreaves, 1994). Teachers have consciously aimed at a professional position by emphasizing their educational and subject specific expertise. (Ropo and Värri 2003, p. 306)

Knowledge is important but may not be sufficient anymore. My main argument here is that the construction of identity is more important than ever before. There are several reasons for this. The first is identity’s roots in the Enlightenment and the early history of education (see Giddens 1991). According to its main message, people could be emancipated from their wild nature by education. Education became a common interest for nation-building because it was soon understood that educated people were useful for the cohesion of the nation and increasing the welfare of society (Ropo and Värri 2003).

The second reason is the current trend from collective to individual identities. Education as a provider of competences or qualifications is no longer the only capital for good life. Like Côté (2005) has suggested, identity can be regarded increasingly as capital needed in life (see also Goodson 2006). Identity is capital to be used in individual decision-making in the turbulence of work and private lives.

Third, identity is negotiated and expressed in relationships, and from this point of view, recognizing one’s identity has become a necessity. If the nature and context of the relation changes identity has to be reconstructed. Like many researchers argue, we do not have a single identity, but many. Some parts of our identities are always under reconstruction, while some may be more stable over time.

The fourth reason refers to the relations between learning and identity processes. Like learning, identity should not be regarded as a fixed construct, or a characteristic of a person that is reached at some point of age or life, but a process. To understand the nature of a process, we need the concept of identitypositioning (e.g. van Langenhove and Harré 1999). Positioning and repositioning are important ways to influence the perspective that we have in the relations to people, problema or phenomena. Repositioning changes the meanings constructed during the negotiations, and the new meanings affect our identity. Temporal and embodied positioning are also important phenomena in our meaning making. Like Merleau-Ponty (1986) has pointed, identity is composed in the processes of interpreting and synthesizing our experiences in the flow of temporality.

In summary, we may argue that for education to survive in the turmoil of information age and the new order, it is necessary to first understand and then react. Schools need to be provided with tools and concepts to guarantee its success. We need to educate productive, healthy citizens for the future despite the lack of descriptions of either the future world or its requirements. Continuous reconstruction of one’s identity is not only an individual question. It is also the necessity of the schools and teachers to provide required support for this process.

After arguing for the importance of and potential for which identity may have in education, I will discuss the implications of identity theorizing for the design of curricula and processes related to understanding identitynegotiations as the main processes of learning and human development.

Autobiography, Narratives and Identities

How does the concept of identity make education different from what it is now? The question for a researcher studying life history and autobiographical identity is “Who I am and where do I come from?” There are also many why questions that might be reflected on when creating and reconstructing your own narratives of life. Understanding these “whys” is crucial for understanding your learning, interests, decisions, and motivation.

I will start with a narrative of myself to illustrate the importance of the reflection of life history in the construction of identities and positioning to life. This reflective negotiation is crucial to surviving crises, but it is also important in many other respects such as creating dreams and aspirations to become, the will to achieve, or values in conducting one’s life.

I was born to Karelian parents in post-war Finland. My mother was a so-called evacuee, born in 1918 in a small village close to the city of Vyborg. Evacuees were people who had to leave their homes (in 1940 and 1944) after the wars and who moved to other regions in Finland because the border between Finland and the Soviet Union was changed. In the peace treaties (1940 and 1944), areas of Eastern Finland and one part of the region of Karelia including Vyborg and the vicinity were merged with the Soviet Union. Life conditions in the early years of Finnish independence (1917) were hard in many respects. My mother had lost her own mother when she was eight weeks old because of the 1918 influenza pandemic (Spanish Flu), which also took other lives all over the Europe and the world. Later on, my grandfather remarried a local lady, and they had four other children. School legislation from 1921 guaranteed a few years of basic education to all. However, it was impossible for poor rural families to send their children to secondary education in towns like Vyborg. My mother skipped the first grade because of already being able to read and write. She went to school for five years. Work in a small family farm and on relatives’ farms was the expectation for a countryside teenage girl.

War ruined young people’s dreams like it does now. In the Winter War (1939–1940), my mother worked as a dairy worker in her Karelian home village with two teenage girls to provide soldiers with milk and butter. All other people were already evacuated, and life close to the front was full of fears for these young ladies. In the so-called Continuation War in 1941–1944, my mother lost her younger brother during the last months of the war in July 1944. He was just a young 20-year-old soldier.

My father was also a south Karelian, the oldest son in the family of 10 children. His three older brothers had died during their first five years of life. He was the first to survive. Five younger brothers and a sister, who all lived long, were born between 1918 and 1938.

Reflecting on the story of my parents, it is very hard to imagine what inspired their imaginations and dreams for life. Building positive identities as children and young people in such conditions must have been hard, but still they had no other option. Diseases had taken lives of family members, access to education was very limited, and the war had destroyed the dreams of the entire generation. More than 90,000 soldiers were killed, and almost every family lost one or more of their family members. How can anyone construct a healthy identity in those conditions?

I think the melancholic atmosphere in my childhood was mostly due to the emotional suffering of my parents and their whole generation. Those feelings and emotions were not shared with children. Men talked about war experiences only with each other, sometimes only after drinking alcohol. In public, the message was to forget and continue life. Church and religion were ways to overcome bad feelings. A positive outcome was that the country remained independent.

After the war, people tried to take back what the war had postponed in their personal lives. Record numbers of children were born during the first three years of war. The country was rebuilt and the war debts paid. My parents’ perspective on life was focused on work and education. They felt that children should be given an opportunity to go to school to have a better life than themselves, although they went to school only for a few years.

School indeed made a change for the expectations and future thoughts of my sisters and me. Since there was not a “script” from our parents, such as farming or a family business, it was evident that education was the only route to independent adulthood.

Finnish education in the 1960s was based on a dual system in which so-called folk school comprised seven years of education leading to vocational schools and worker careers. From grades 4 to 8, it was possible to apply to eight years of secondary education leading to a matriculation examination and university studies. My sisters and I were all admitted to secondary education.

Autobiographical narratives such as the one given here work at their best as tools for repositioning. In my current understanding, it was the prospect of a different future offered by the school that changed the identity of an evacuee’s son to thinking of something bigger. The school made it possible to reposition myself with respect to my future dreams of work and career.

School progressed rather well Knowledge, skills, and understanding increased, and there were suddenly many more options to choose from than my parents had ever had in their lives. Identity as a capital to be used in selecting between optional futures seemed to work. Capital meant courage to take risks and trust in the positive future of offering something good. It is also necessary to reposition when your plans get ruined for one reason or another. This kind of identity capital comes from several sources. Some of it originated in my case from acknowledged strengths, knowledge and performance in school. This is hard to separate from the encouragement received from teachers who in some immeasurable ways could create positive prospects for life.

As a result of reflecting on my narrative, I have realized that I benefited a lot from the secondary teachers who were all educated at universities. They had adopted a collegial and supportive position towards their students. In my childhood, there was also a family friend, an evacuee and an older “uncle,” who had been working as a forestry foreman. While playing chess together, we talked a lot about my future. He encouraged me to study as far as a master’s degree, which for his generation was a sign of belonging to societal upper class. Reflecting on my childhood, it was evident that this kind of support from outside the nuclear family made me ponder different options for the future and also for my initial and most desired career plan of becoming a military pilot.

To understand and verbalize who I am, where I come from, and where I belong, I need to create and understand my story. I have realized that life stories cannot just be adopted from someone else. The story is not personal unless it becomes associated with your autobiographical memory, your own experiences and the meanings you have created by reflection (see Kihlstrom et al. 2003). These stories are never ready or fixed. They are temporally and historically rooted in times and places but also in times and contexts of creation and reflection. The stories are connected to complex social networks of people, institutions and events. They all come alive when we create a plot and meaning that connects the history to our own experiences. These stories describe me and my positioning. However, I am not only the stories. As Ivor Goodson (1998) points out:

It is important to view the self as an emergent and changing ‘project’ not a stable and fixed entity. Over time our view of our self changes and so, therefore, do the stories we tell about ourselves. In this sense, it is useful to view self-definition as an ongoing narrative project. (p. 11)

Autobiographical narratives work as anchors to place one’s life course in chronological time and contexts, geographical places and environments, and the conditions of everyday lives. Interpretations of these narratives contextualize them into your own story allowing the construction of personally relevant meanings. These meanings are then used in further reflections as part of your own identity narratives. The reflected narratives comprise the capital for identity repositioning as a resource in future life contexts. Reflecting can make a difference in one’s life, like it did in my own case. However, storying one’s life in such a detail and reflecting it by positioning oneself as an outsider may be, for growing children and young people, a different and sometimes more difficult problem than for adults.

Narrative Nature of Existence

So far I have described identity development as a narrative process in which we construct stories of our own lives to understand through reflection of who we are and our relation to the world outside of us. Those stories are then reconstructed, reinterpreted and reflected upon during the turns and experiences of life. The result of such narrative processes can typically be described as feelings of knowing and understanding but also as emotional states such as belonging, love, joy, anger or frustration. This being a personal experience, can we relate this to the theory of narrativity?

Hanna Meretoja (2014) has suggested, in her recent book The Narrative Turn in Fiction and Theory, that the narrative turn in literature,

is characterized by acknowledging not only the cognitive, but also the complex existential relevance of narrative for our being in the world. From this perspective I suggest conceptualizing it as a shift towards a hermeneutically oriented understanding of the ontological significance of storytelling for human existence. (p. 6)

According to this theory, stories or narratives are crucial to understanding existence. Understanding is a complex process but for the current purpose we say, for instance, that in the understanding process, the elements of a story are connected with personal memories or autobiographically meaningful associations to temporally, situationally, and contextually relevant plots. This is the connection to the concept of learning. Autobiography influences what we learn and what we are able to construct into stories. This process is never complete.

An important ontological question concerns the role of narratives for human existence. For instance, to what extent do people make sense and understand their existence and whole reality in terms of narratives (Meretoja 2014)? An important question related to this is how true and realistic are the narratives of existence that we create through our perceptions and construction processes? For a narrative researcher, however, these questions are in a way irrelevant. Narratives or stories are always constructed from a certain perspective or, to be more exact, an identity position. Subsequently, they are always personal, social and cultural interpretations of existence. Those different layers in our positioning are all evident and relevant. Narratives connect the events and experiences with timelines, contexts, meanings, and plots.

In the literature on narrative, there is no total agreement about terminology. Should we speak of meanings, or experiences, or both? I have referred to reflection as a process to construct personally meaningful narratives. According to Meretoja (2014), meaningful connections between experiences are important but there is no agreement in what ways. Those who refer to the phenomenological-hermeneutic tradition and narrative psychology typically prefer the concept of experience. They are typically interested in narratives as a practice through which subjects make sense of their experiences and exchange them with others (see Ricoeur 1984).

In the narratological tradition, narratives are typically approached in terms of events, or representations to create the links and causal chains of events. For narratological researchers, therefore, experience is not an interpretation or meaning of events, but rather a mental representation of an event.

In an earlier article, we referred to human information processing as aiming at constructing a representation of the acquired information (Yrjänäinen and Ropo 2013). The result of this process can be a verbalized story or something that can be verbalized as a story. However, this story is often partial and incomplete from the point of understanding. Understanding or creating meanings is a process of elaboration or a reflection of the representation and its associations to earlier memories, experiences, narratives and knowledge that the person may already have. This can also be illustrated with a metaphor of negotiation. We can also negotiate with our representation or narrative. Sometimes this negotiation is a kind of inner speech, sometimes it is enhanced by reflections with others. Writing, drawing or some other creative ways of expression can also enhance the construction and reflection of our narratives.

An important question among those who see narratives as important in organizing and interpreting experience is whether narratives are fundamentally ontological (what is) or epistemological (meanings). Do we actually perceive the world as narrative through the narratives, or do we use narratives to make sense of our experiences and create only the meanings related to our perceptions? Like Meretoja (2014), we can ask if the narratives are a kind of cognitive device, or rather are instruments with which we recognize and make sense of reality, create meanings, and make our experiences and the realities around us more meaningful.

I prefer the view that narratives are important both from ontological and epistemological points of view. We do not seem to have direct access to reality, and we do not seem to construct knowledge in any other way than through representations that have similar properties than verbalized narratives, these being realistic to our perspective or positioning during the information acquisition stage and incomplete at the same time, filled with details but concurrently also having open slots of the aspects unknown to us. This is the process of constructing narratives of identities. Identities exist ontologically in the narratives that are under a process. Whether they are based on something other than narratives is a question that we can now leave as open. Epistemologically, sense-making is a process in which we create and negotiate, reconstruct and struggle for better understanding between description and causality (Goodson et al. 2010). The crucial point here is not only learning from stories but also through the reconstruction of stories. This kind of learning becomes possible if, first, the person feels willing to change his/her narrative identity, and second, the change in the identity becomes real through the reconstruction of a new story in which the details support the renewed interpretations of oneself (Ropo and Värri 2003).

The same kind of narrative process can be assumed to apply to children, as well. When thinking of identitynegotiations in childhood, the family typically offers the basic family narratives. An individual’s positions in those narratives are usually offered, for instance, in terms of age, gender or order of birth. Those narratives are supported by real-life perceptions of parents, siblings, extended family and so on. Narratives become ontologically realistic when people exist both in the real and in the stories; however, epistemologically the child has to interpret and understand who these people are and what kind of meanings to attach to them in his/her own narratives. All human knowledge is like this, narratives constructed out of perceptions, and acquired information. Those narratives have empirically and phenomenologically proven elements, concurrently being vague and open in some respects (Yrjänäinen and Ropo 2013).

Paul Ricoeur’s (1987) three-stage Mimesis process is an excellent description of the narrative construction and negotiation. The first phase in the narrative formation is the level of perception, actions and experiences (Mimesis1). In the second phase (Mimesis2), those experiences serve as raw material on which the narrator takes a stand for the creation of initial narratives. The third level (Mimesis3) relates to how the created narratives are applied and returned to the level of perceptions, actions and experiences (Mimesis1), as the basis for interpreting new information.

This model can also be applied to schoollearning. Particularly in the domains of subject-specific learning, the narrative learning model seems very appealing (Yrjänäinen and Ropo 2013). The first phase (Mimesis1) is the pre-knowledge and perception stage. We perceive, interpret and experience phenomena on the basis of our previous knowledge of the phenomena. Typically, these kinds of perceptions and predictions are based on naïve theories learned in everyday life. The second stage (Mimesis2) concerns the group processes and classroom discourses in which the previous knowledge is challenged, experiments made, new information and concepts offered, and rules and theories developed. Teachers’ goals in this stage are typically to enhance the creation and construction of scientifically correct and socially accepted, shared meanings. The third stage (Mimesis3) deals with the process of applying the new narratives of the phenomena in the new perceptions to come. In this kind of learning, we typically construct narratives based on personal (or autobiographical) meanings, socially shared meanings (community, class), and culturally shared (scientific) meanings. These are negotiated to a narrative with a plot to understand the different aspects of the phenomenon. The teacher’s task, defined in the curriculum, is to ensure that scientific meanings dominate in the students’ narratives concerning the topic, phenomenon, or domain, such as gravity, force or electricity.

To summarize, I have hypothesized that the narrative turn in understanding human ontology and epistemology pertains also to understanding learning. In this sense, learning about me, others and the world are similar narrative negotiation processes in which we create stories, reconstruct them through reflection, thinking and problem-solving, and apply them to perception and acquisition to refine the narratives towards personally, socially and culturally accepted and shared narratives and understanding of the phenomena and us as part of them.

Identity Negotiation and Curriculum

If we argue that learning is a narrative process in which we negotiate meanings by positioning ourselves in terms of autobiographical, social and cultural perspectives, the question is how to apply this theorizing in rethinking about curricula. For example, in Latin the word curriculum denotes: (1) racing (men or horses), (2) one round in a racing course, and (3) a racing course. However, the most current way of understanding the concept of curriculum has not involved a process of proceeding on a life course. According to the ideas of the German Lehrplan, curriculum denotes a description of a given course of a given subject at school or other educational institution. This curriculum is a plan for learning. The current Finnish model of curriculum includes descriptions of aims, contents, teaching methods and descriptions of assessment following the so-called Tylerian model (see Tyler 1949). The Tylerian curriculum model is problematic, and to mention just one problem, it is difficult if not impossible to specify exact instructional methods to achieve particular goals, aims or objectives. The more prescriptive the curriculum is, the less it gives teachers options for teaching in a way that allows students to benefit from teachers’ own situational intuitions, knowledge of individual students, and narratives of phenomena. If the required performance is described as achievement standards, it is in this respect even more harmful for teachers’ work as facilitators of learning.

Without going into more detail about the problems of the current curricular models, I argue that a curriculum can be viewed as an imaginary space or microcosm within which the teachers and students should explore, process and negotiate, in continuous discourses about the inputs, materials and challenges (see Ropo 1992). This microcosm is a space not just for a learning purposes, but living, growing and learning to know what there is to know (ontology) and understanding (epistemology) in terms of personal, social and cultural and historical identity perspectives. This kind of understanding of curriculum is close to the classical definition of the term curriculum.

Naturally, there is a lot of theorizing in the history of curriculum. Such concepts as experience, autobiography or life history are familiar from this literature. For instance, Bobbitt (1918/1972) defines the curriculum as a series of, or a continuum of, matters that children must perform or live through. Bobbitt (1972) gives a two-way definition of curriculum. First, a curriculum can be a series of experiences whose purpose is to unfold the children’s talents. These experiences can be intentional and directed, or without a teacher’s support. Second, Bobbitt (1972) defines curriculum as the entire range of intentionally planned and directed experiences from teaching at school with a view to unfolding and perfecting the child’s abilities.Footnote 1 To Bobbitt, the purpose of education is to open up the future for children by helping them to find their strengths and sources of interests.

William Pinar (1994) emphasizes the close similarity between autobiographical processes and curriculum. Pinar developed an autobiographical method which he named the “currere method” and in turn is based on a reflective examination of school subjects and personal life histories for the purpose of gaining a better understanding of one’s self and reconstructing one’s identity. The currere method comprises four phases: a regressive phase (return to the past: what has been), a progressive phase (a step into the future: what is going to follow, what is the future going to be like), an analytical phase (simultaneous reflection on the past and the future) and a synthetic phase (return to the present). The phases are related to the ways in which individuals in different phases process or reflect on their personal experiences and life histories.

Although Pinar never recommends the method as such for school teaching, it provides an interesting view on increasing the narrative quality of teaching. The result of this kind of reflection can be expressed in the form of narratives, if the user of the method so wishes. To think of school as a pedagogical microcosm is rather an enchanting metaphor, albeit with certain reservations. A microcosm as such is no guarantee of discursive processes in which personal autobiographical narratives can be reconstructed. What narratives come out of it in the minds of the participants depend on the extent of negotiations and individual reflections. Very often all of this remains unknown to the teachers.

Curriculum for Enhancing Narrative Negotiation

Curricula typically contain subject- or domain-specific descriptions of aims, goals and objectives. They may also specify the materials, teaching methods, and assessment criteria for teachers to follow. The purpose of the specificity is, for instance, to increase the transparency of education and its results, to reduce differences and to guide teachers’ and educators’ work. Still, the problem of relevance and meaningfulness of goals, objectives and applied methods for the students remains. I suggest that in enhancing the narrative negotiation, not only in schools but also generally in education, we have to consider individuality from totally different points of view than we are used to. Individuality does not as much relate to differences in intelligence or talents, but more to student experiences of meaningfulness. To open up discourses related to meaningfulness, I suggest more explicit application of autobiographical, social and cultural positioning in enhancing narrative negotiations in education. Those positionings can be applied to, for instance, locally and globally important issues. The positionings are described in the Table 9.1 separately, although we can assume that they are closely connected and intertwined.

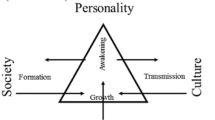

This kind of curriculum does not prescribe teachers’ autonomy in deciding the best methods for reaching the goals. However, the thinking is increasingly based on recognizing the importance of students’ identity positioning in processing of meanings and meaningfulness towards the topics and phenomena dealt with in instruction. We may infer that all three perspectives of positioning need active decision-making from a student. Autobiographical positioning searches for meanings from personal resources, life experiences, life contexts, bodily experiences, dreams and hopes, beliefs of efficacy, confidence and so on. This search can be contextualized to both local and global perspectives. I may ask what my resources are in the local context and what they are globally. Social positioning relates to membership, belongingness and ways of strengthening the membership by adopting and accepting common values, habits and knowledge bases (see Wenger and Lave 1991). Looking at the issues from the member position, or the local or global perspective leads to different types of meanings. Cultural and global positioning involves seeing one’s own life, the lives of others, history, culture and future from a more abstract, “birds eye view” perspective. Ideologies, religions, political and environmental values and positioning are good examples of this kind of positioning perspective.

The model I am suggesting here indicates the importance of identity positioning as a concept. Meanings are created in complex contexts through discourses and conversations in which perspectives and contexts are important.

In this chapter, I do not suggest or introduce methods for this kind narrative negotiation. I do believe that methods are not the biggest problem in adopting the idea. Turning the mindsets from learning and learning results to a new paradigm of seeing schools and educational institutions, and curricula, as spaces and places for narrative negotiation is the biggest challenge. There are promising signs from teacher education, professional education and even in public basic education showing that some teachers are actually implicitly applying this type of method. In foreign language education, for instance, the autobiographical approach has expanded into a popular method (Kohonen et al. 2014). Teacher education has also been shown to benefit by applying the ideas presented in pre-service teacher education (Yrjänäinen 2011) and pilot studies in basic education of enhancing narrative negotiations show that students’ acquirements and willingness to position-taking expands from autobiographical towards social and cultural during the school years (Kinossalo 2015). Hopefully, this kind of theorizing I suggested will help to understand better the complexity of internationalizingcurriculum conversations.

Concluding Remarks

Education is a complex system and changing it is a slow process. Political demands for the transparency of measured results have increased leading to increased standardized testing in schools. Autonomy of schools and teachers has in practice been reduced in many countries. Before we educators lose the political battle of the nature of education, it is time to challenge the simplistic views of the results of education being only competences or skills measurable with tests and exams. Curriculum as a societally accepted, intellectual space for narrative negotiations may not be a new idea among researchers. I believe that seeing learning as a process of complex identity negotiation in differing contextual spaces that I have suggested is at least one of the directions to proceed.

Notes

- 1.

“The curriculum may, therefore, be defined in two ways: (1) it is the entire range of experiences, both undirected and directed, concerned in unfolding the abilities of the individual; or (2) it is the series of consciously directed training experiences that the schools use for completing and perfecting the unfoldment. Our profession uses the term usually in the latter sense” (Bobbitt 1918/1972, p. 43).

References

Alcoff, L. M., & Mendieta, E. (2003). Identities: Race, class, gender, and nationality. Oxford: Blackwell.

Bobbitt, J. F. (1918/1972). The curriculum. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Brubaker, R., & Cooper, F. (2000). Beyond “identity”. Theory and Society,29(1), 1–47.

Bruner, J. S. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Côté, J. (2005). Identity capital, social capital and the wider benefits of learning: Generating resources facilitative of social cohesion. London Review of Education,3(3), 221–237.

Côté, J. (2006). Identity studies: How close are we to developing a social science of identity?—An appraisal of the field. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research,6(1), 3–25.

Côté, J. E., & Levine, C. G. (2002). Identity, formation, agency, and culture: A social psychological synthesis. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Erikson, E. H. (1959). Identity and the life cycle. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company. Reprinted in 1994.

Finnish National Agency for Education. (2004). National core curriculum 2004. Retrieved from http://www.oph.fi/english/curricula_and_qualifications/basic_education/curricula_2004.

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Goodson, I. F. (1998). Storying the self: Life politics and the study of the teacher’s life and work. In W. F. Pinar (Ed.), Curriculum, toward new identities (pp. 3–20). New York: Garland Publishing.

Goodson, I. (2006). The rise of the life narrative. Teacher Education Quarterly,33(4), 7–21.

Goodson, I. F., Biesta, G., Tedder, M., & Adair, N. (2010). Narrative learning. New York: Routledge.

Kihlstrom, J. F., Beer, J. S., & Klein, S. B. (2003). Self and identity as memory. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (pp. 68–90). New York: Guilford Press.

Kinossalo, M. (2015). Oppilaan narratiivisen identiteetin rakentumisen tukeminen perusopetuksessa [Enhancing narrative negotiations of identity in basic education]. In E. Ropo, E. Sormunen, & J. Heinström (Eds.), Identiteetistä informaatiolukutaitoon: tavoitteena itsenäinen ja yhteisöllinen oppija [From identity to information literacy: Towards independent and social learner] (pp. 48–82). Tampere: Tampere University Press.

Kohonen, V., Jaatinen, R., Kaikkonen, P., & Lehtovaara, J. (2014). Experiential learning in foreign language education. New York: Routledge.

Lannegrand-Willems, L., & Bosma, H. (2006). Identity development-in-context: The school as an important context for identity development. Identity,6(1), 85–113.

Leary, M. R., & Tangney, J. P. (Eds.). (2011). Handbook of self and identity. New York, NY: Guildford Press.

Limberg, L., Alexandersson, M., Lantz-Andersson, A., & Folkesson, L. (2008). What matters? Shaping meaningful learning through teaching information literacy. Libri,58(2), 82–91.

Marcia, J. E. (1994). The empirical study of ego identity. In H. A. Bosma, T. L. G. Graasfma, H. D. Grotevant, & D. J. De Levita (Eds.), Identity and development: An interdisciplinary approach (pp. 67–80). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

McAdams, D. P., Josselson, R., & Lieblich, A. (Eds.). (2006). Identity and story: Creating self in narrative. Washington, DC: APA.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self and society (Vol. 111). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Meretoja, H. (2014). The narrative turn in fiction and theory: The crisis and return of storytelling from Robbe-Grillet to Tournier. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1986). Phénoménologie de la perception [Phenomenology of perception]. London: Routledge (Original publication, 1945).

Pinar, W. F. (1994). Autobiography, politics, and sexuality. New York: Peter Lang.

Ricoeur, P. (1984). Time and narrative (K. McLaughlin & D. Pellauer, Trans.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ricoeur, P. (1987). Time and Narrative III. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Ricoeur, P. (1991). Narrative identity. In D. Wood (Ed.), On Paul Ricoeur: Narrative and interpretation. London: Routledge.

Ropo, E. (1992). Opetussuunnitelmastrategiat elinikäisen oppimisen kehittämisessä [Curriculum strategies for developing lifelong learning]. Kasvatus, 23(2), 99–110.

Ropo, E., & Värri, V.-M. (2003). Teacher identity and the ideologies of teaching: Some remarks on the interplay. In D. Trueit, W. E. Doll, H. Wang, & W. E. Pinar (Eds.), The internationalization of curriculum studies (pp. 261–270). Selected Proceedings from the LSU Conference 2000. Peter Lang. ISBN 0-8204-5590-3.

Taylor, C. (1989). Sources of the self. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tyler, R. W. (1949). Basic principles of curriculum and instruction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Van Langenhove, L., & Harré, R. (1999). Introducing positioning theory. In R. Harré & L. van Langenhove (Eds.), Positioning theory (pp. 14–31). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Weigert, A. J., Teitge, J. S., & Teitge, D. W. (1986). Society and identity: Toward a sociological psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wenger, E., & Lave, J. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation (Learning in doing: Social, cognitive and computational perspectives). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Yrjänäinen, S. (2011). ‘Onks meistä tähän?’ Aineenopettajakoulutus ja opettajaopiskelijan toiminnallisen osaamisen palapeli [‘But really, are we the right sort of people for this?’ The puzzle of subject teacher education and the teacher student professional practical capabilities]. Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 1586. Tampere: Tampere University Press.

Yrjänäinen, S., & Ropo, E. (2013). Narratiivisesta opetuksesta narratiiviseen oppimiseen [From narrative teaching to narrative learning]. In E. Ropo & M. Huttunen (Eds.), Puheenvuoroja narratiivisuudesta opetuksessa ja oppimisessa [Conversations on narrativity in teaching and learning]. Tampere: Tampere University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ropo, E. (2019). Curriculum for Identity: Narrative Negotiations in Autobiography, Learning and Education. In: Hébert, C., Ng-A-Fook, N., Ibrahim, A., Smith, B. (eds) Internationalizing Curriculum Studies. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01352-3_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01352-3_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-01351-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-01352-3

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)