Abstract

When is an indirect report of what a speaker meant correct? The question arises in the law. The Contract Law case of Spaulding v. Morse is a good example. Following their 1932 divorce, George Morse and Ruth Morse entered into a trust agreement in 1937 for the support of their minor son Richard. In that agreement, George promised to “pay to [Spaulding as] trustee in trust for his said minor son Richard the sum of twelve hundred dollars ($1200) per year, payable in equal monthly installments on the first day of each month until the entrance of Richard D. Morse into some college, university or higher institution of learning beyond the completion of the high school grades, and thereupon, instead of said payments, amounting to twelve hundred dollars ($ 1200) yearly, he shall and will then pay to the trustee payments in the sum of twenty-two hundred dollars ($ 2200) per year for a period of said higher education but not more than four years.” Richard graduated from high school on February 5, 1946 and, in the post-WWII continuation of the draft, was inducted into the army the following day. The question in the case is whether George, by the words of the trust agreement, meant that he would pay $1200 per year for Richard’s support while he was in the army. Is that a correct indirect report of what George meant?

The explanation I offer assumes Gricean analysis of speaker meaning, and it emphasizes the role of speaker meaning typically plays in solving coordination problems. A coordination problem is a situation “in which each person wants to participate in a group action but only if others also participate.” A classic example is a political protest: “each person might want to take part in an antigovernment protest but only if there are enough total protesters to make arrests and police repression unlikely.” Coordination problems arise in more mundane settings as well—in Spaulding v. Morse, for example. Ruth and George want to mutually agree on Richard’s support: Ruth wants to commit to an arrangement only if George does, and vice versa for George. In 1937, George and Ruth solved the problem through speaker meaning. By signing the trust agreement, George, with Ruth as his audience, meant that he obligated himself to a particular support agreement. When Ruth signed, she, with George as her audience, meant that she accepted the agreement. In general, parties often solve coordination problems through speaker meaning. If, for example, enough people can communicate their commitment to participate in the protest to enough people, the protest will take place.

The account assigns a central role to the fact that speaker meaning facilitates coordination by creating relevant common knowledge. Common knowledge is “the recursive belief state in which A knows X, B knows X, A knows that B knows X, B knows that A knows X, ad infinitum.” Common knowledge facilitates coordination: “Actors coordinate when they have evidence for common knowledge, and refrain from coordinating when they do not.”

I am very much indebted to Steven Wagner for comments on an earlier draft.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

Spaulding v. Morse, 76 N.E. 2d 149 (Supreme Court of Massachusetts 1947).

- 2.

Ibid.

- 3.

The answer revises an approach I took in an earlier article, Richard Warner, “Coordinating Meaning: Contractual Promises, Common Knowledge and Coordination in Speaker Meaning,” in Alessandro Capone (Ed.), Further Advances In Pragmatics And Philosophy, Springer, forthcoming.

- 4.

I assume a distinction between what a speaker means by an utterance on a particular occasion, and the standard meaning of a sentence (word, or phrase) in a natural language.

- 5.

Michael Suk-Young Chwe, Rational Ritual: Culture, Coordination, and Common Knowledge (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013).

- 6.

Michael Suk-Young Chwe, Rational Ritual.

- 7.

Kyle A. Thomas et al., “The Psychology of Coordination and Common Knowledge,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 107, no. 4 (2014): 657.

- 8.

Ibid.

- 9.

Utterances may include not just sounds and marks but also gestures, grunts, and groans—anything that can signal an M-intention.

- 10.

H. P. Grice, “Meaning,” Philosophical Review 66 (1957): 337.

- 11.

Chomsky has repeated emphasized this point. See, for example, Noam Chomsky, Powers and Prospects: Reflections on Human Nature and the Social Order, 1st PB Edition (Boston, MA: South End Press, 1999).

- 12.

There is a great deal more to be said about the role of reasoning in guiding utterances and responses, but, as interesting as the issues are, I put them aside.

- 13.

Compare Grice’s remark on optimal states of speaker meaning in Paul Grice, “Meaning Revisted”, in Paul Grice, Studies in the Way of Words (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1991).

- 14.

In Gricean terms, Roger cancels a conversational implicature. The example is from H. P. Grice, “The Causal Theory of Perception,” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society Supp. nqv 1961 (1961): 121.

- 15.

This raises a number of interesting issues I put aside.

- 16.

Bernard Williams, Truth and Truthfulness: An Essay in Genealogy, 1.3.2004 edition (Princeton University Press, 2004), 24.

- 17.

Alessandro Capone, The Pragmatics of Indirect Reports (Springer, 2016), 21–48, eps. 28-32.

- 18.

Grice views propositions as a necessary theoretical construct in “Reply to Richards”, in Richard E. Grandy and Richard Warner, eds., Philosophical Grounds of Rationality: Intentions, Categories, Ends (Oxford Oxfordshire : New York: Oxford University Press, 1986).

- 19.

See Stephen Schiffer, Meaning (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973). Schiffer’s interesting analysis is much more complicated as it addresses a wide range of possible counterexamples, handles all types of speech acts, and incorporates Schiffer’s seminal analysis of common knowledge.

- 20.

This paragraph and the next two are adapted from Richard Warner, “Coordinating Meaning: Contractual Promises, Common Knowledge and Coordination in Speaker Meaning,” in Alessandro Capone (Ed.), Further Advances In Pragmatics And Philosophy, Springer, forthcoming.

- 21.

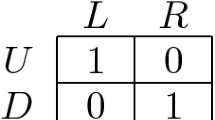

The game goes by a variety of names besides assurance game. Others are Trust Dilemma, Coordination Game, and Stag Hunt. William Poundstone, Prisoner’s Dilemma 219 (1992).

- 22.

In addition, the parties are unable to communicate, and each chooses without observing or otherwise learning about the choice of the other. These assumptions, and the joint knowledge of one another’s preferences, are the classic assumptions of game theory. See generally, e.g., Kevin Leyton-Brown, Essentials of Game Theory: A Concise, Multidisciplinary Introduction (2008); Martin J. Osborne & Ariel Rubinstein, A Course in Game Theory (1994).

- 23.

For a fuller discussion see, Richard Warner, “Coordinating Meaning: Contractual Promises, Common Knowledge and Coordination in Speaker Meaning,” in Alessandro Capone (Ed.), Further Advances In Pragmatics And Philosophy, Springer, forthcoming; Robert H Sloan and Richard Warner, “The Self, the Stasi, and the NSA: Privacy, Knowledge, and Complicity in the Surveillance State,” Minnesota Journal of Law, Science, and Technology 17 (2016): 347.

- 24.

Thomas et al., “The Psychology of Coordination and Common Knowledge,” 659.

- 25.

The seminal technical treatment is John C. Harsanyi, “A New Theory of Equilibrium Selection for Games with Complete Information,” Games and Economic Behavior 8, no. 1 (1995): 91–122.

- 26.

The use/mention confusion here is harmless and eliminable.

- 27.

I discuss these cases in, “Coordinating Meaning: Contractual Promises, Common Knowledge and Coordination in Speaker Meaning,” in Alessandro Capone (Ed.), Further Advances In Pragmatics And Philosophy, Springer, forthcoming.

- 28.

See Richard Craswell, “Contract Law: General Theories”, in Boudewijn Bouckaert and Gerrit De Geest, eds., Encyclopedia of Law and Economics (Cheltenham, UK ; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Pub, 2000).

- 29.

Spaulding v. Morse, 76 N.E. 2d at 153. 152

- 30.

Ibid. 153

- 31.

Spaulding v. Morse, 76 N.E. 2d. 154

- 32.

Ibid.

- 33.

See Richard Craswell, “Contract Law: General Theories”, in Bouckaert and Geest, Encyclopedia of Law and Economics.

- 34.

Lozman v. City of Riviera Beach, Fla/, 568 U. S 115 (United States Supreme Court 2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Warner, R. (2019). Indirect Reports in the Interpretation of Contracts and Statutes: A Gricean Theory of Coordination and Common Knowledge. In: Capone, A., Carapezza, M., Lo Piparo, F. (eds) Further Advances in Pragmatics and Philosophy: Part 2 Theories and Applications. Perspectives in Pragmatics, Philosophy & Psychology, vol 20. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00973-1_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00973-1_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-00972-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-00973-1

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)