Abstract

The role of sustainability strategic management is receiving more attention from scholars and practitioners in recent years. However, several aspects of a possible integration of business strategy and sustainability strategy remain unclear. With the aim of filling this gap in the literature, a conceptual paper is proposed by analysing some barriers and possible managerial enablers, presenting a sustainable strategic management framework. The primary purpose of this paper is to develop a reasonable and integrated approach to corporate responsibility undertaken by companies actively operating in Poland. The integrated approach also means that the theoretical dimension is closely linked to practical aspects, based on experience in working with managers. It has some practical relevance—the perspectives on strategic approach to sustainability developed in this paper would help managers to design internal processes in a more effective and efficient manner. This paper can be useful to international scholars for further strategic management framework development and improvement.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) has a long history, but the remarkable dynamics of the various theoretical concepts and practical applications can be seen especially in recent years. There are many studies that present a detailed history of the development of different frameworks for CSR (Crane et al. 2008; Rok 2013). When analysing the development of the CSR at the company level it can be stated that general declarations of a moral nature and discussions about the scope of the principle of stewardship were replaced with a more holistic vision of corporate responsibility or corporate sustainability as the foundation of a new business paradigm, grounded to a certain degree in management theory. In the context of the evolution of CSR—as an umbrella concept—towards corporate sustainability or corporate strategic responsibility, businesses are confronted now with the imminent challenge of adapting deep strategic orientation toward Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Avery 2017; Kolk et al. 2017).

Corporate responsibility can be one of the most important dimensions—if not the foundation—of an effective strategy, resulting from the objectives and priorities adopted by business leaders and managers. It is often said that incorporating CSR principles into a company strategy may lead not only to social benefits for stakeholders, but also—at least in some cases—to tangible business benefits. Some researchers in Poland are pointing out that the corporate social responsibility can be a source of competitive advantage of a company, provided that the activities are rightly undertaken. Main business benefits are: the boost of the firm’s confidence, the improvement of its reputation on the market and the increase of employees’ loyalty, what can lead to the improvement of companies’ long-term performance and competitive advantage (Ceglinski and Wisniewska 2017). On the global scale, in a research study conducted already a few years ago it was noted that out of 100 randomly selected companies from the Fortune 500 only one third declared in its mission that its goal is to maximise value for shareholders, and the remaining declared that their goal is to maximise the well-being of all stakeholders (Agle et al. 2008).

The question remains, however, how to incorporate CSR into business strategy? Perhaps the CSR strategy should be developed independently and only refer to the business strategy to some extent, i.e. supplement it? CSR strategy could be a part of a business strategy or just the opposite (Bove and Empson 2013). In some cases, one can easily recognize that business strategy is contradictory to CSR strategy. Therefore, this conceptual paper is aimed at exploring the possibilities for integration of corporate responsibility or corporate sustainability into strategic business framework, providing a theoretical analysis based on the existing literature and the management practice in companies operating on the Polish market.

2 Corporate Responsibility Context in Poland

In the literature on the history of economic and business thought in Poland many statements can be found about corporate responsibility to society as well as the responsibility of business owners, even before the concept of corporate social responsibility really started being analysed scientifically. Typically, reference was made to the concept of philanthropy, although this was not always correct—it would have been better to describe this approach as the social engagement of entrepreneurs. In Poland, this “philanthropic” activity of entrepreneurs developed in earnest already in the second half of the nineteenth century, with industrial development, mainly inspired by positivist ideas (Leś 2001). The activities of people like Kronenberg, Bloch, Norblin or Wawelberg do not only determine the history of industrial development in Poland, but also demonstrate that the idea of corporate social responsibility—understood as activities carried out by entrepreneurs—is not exclusively an “imported product”. Entrepreneurs, together with the representatives of the then Polish aristocracy, outstanding noble families and intellectuals, supported the construction of factory estates, the development of vocational education, healthcare and culture or summer holiday activities for children of poor parents.

But almost till the end of the 1980s issues of corporate social responsibility were discussed nearly exclusively in the US market. It was not until the 1990s that the process of CSR internationalisation and diversification began. From this perspective we can say that CSR came to Poland with only a slight delay compared to other European countries—primarily in the academic community of business ethicists. Already in the late 1990s the first public discussions were held on this topic in the business community—often inspired by non-governmental organisations, while 10 years later the term CSR was used practically on all the websites of the biggest companies in the Polish market. Starting with review articles in magazines for managers (Rok 2000), corporate social responsibility has also become an interesting topic for the general public (see more in the article of Kacprzak in this book). The European policy in the field of CSR has played a major role in the dissemination of this concept. Initially this was because the preparations for EU accession and subsequently—since 2004—on account of participating in the development and implementation of various European policies.

Existing scientific research suggests that CSR is becoming an over-simplified and peripheral part of corporate strategy. Rather than transforming the main corporate discourse, it is argued that corporate responsibility and related concepts are limited to rhetoric defined by narrow business interests and “serve to curtail interests of external stakeholders” (Banerjee 2008). When reading the strategy documents of some of the biggest companies on the Polish market CSR priorities already appear at the level of the mission, vision or corporate values statement. It was a part of the bigger research project conducted by author, so the names of these organizations were hidden, but the dominance of rhetoric was clear at this stage of development in Poland (Rok 2013). For example, the mission of the construction company X refers to the way of conducting its business activities, namely “in accordance with the highest global quality standards, considering the principles of sustainable construction, guided by the principles of professional ethics and attention to user comfort and satisfaction”. In the company Y the mission was formulated as follows: “By setting new trends, offering unique and effective solutions in the interests of human health and life, we focus on those business opportunities that are socially responsible, environmentally friendly as well as economically valuable”. Such a mission can be the basis for a company strategy, according to which the realised business projects are limited to only those that are in line with the principles of sustainable development, although no information confirming such a hypothesis could be found.

Elements of CSR can also be seen at the level of values in company X, as the basic value that is often adopted is responsibility, which can be understood in the following way: “As a socially responsible and conscious firm we work in accordance with our motto ‘people first’ and take care to ensure the safety of our workers. We are also an environmentally friendly company, caring for the natural environment at every stage of our development. We implement specific measures to improve the state of our planet”. In the corporate values statement of company Y, we can read: “We respect our customers, shareholders, the natural environment and local communities”. Such corporate values statements are increasingly being expanded, creating a formal code of ethics, for example.

These statements, however, are often followed by a description of the business strategy, where corporate social responsibility is no longer expressed in any way. Business strategies of companies operating on the Polish market are usually based on certain pillars or overarching objectives, such as building shareholder value, followed by certain priorities or areas within the framework of which the strategic objectives (e.g. maximising the use of existing infrastructure or strengthening the competitive advantage while reducing external risks), planned or already undertaken actions and measures are presented. Usually the mentioned strategic objectives do not include any objectives that directly refer to the principles of corporate social responsibility or corporate sustainability, and that means that CSR is not incorporated into the business strategy.

In the academic literature there is a growing evidence that CSR is beneficial to the bottom line, at least when using a long-term and value creation perspective (Husted et al. 2015), although empirical studies of the relationship between CSR and corporate financial performance have reported mixed findings (Brooks and Oikonomou 2018). For progressive managers on the global market CSR is no longer a purely moral or “social” responsibility for the common good, but increasingly a potential strategic resource to be leveraged to improve corporate financial performance and customer relationships. The concept of CSR has expanded to entail both social, environmental and economic interests at the macro level as well as the organizational level.

According to Porter and Kramer sources of strategic competitive advantage are broadened to include social aspects and social influence (2011). The attractiveness of the CSR and diffusion of related concepts is leading to the amplification of the increasing convergence between CSR and strategy. This strategic turn in the conception of CSR is likely to bring about a shift in corporate practices from reactive attitude and passive compliance with societal expectations to more proactive engagement with social issues, particularly among global market-oriented MNCs who are under monitoring in relation to various aspects of value creation (Yin and Jamali 2016).

Some companies in Poland, usually those that have a comprehensive mission that includes the principles of ethical conduct and social responsibility in greater detail, also have a CSR strategy or a sustainable development strategy. For example, in company Z the mission contains the following statement: “Setting the interest of our shareholders, customers and employees as our main priority, we wish to focus on our reliability and transparency as a partner and to develop the Group’s values in accordance with the principles of sustainable development”. This statement is further expanded as part of the “Sustainable Development and Corporate Social Responsibility Strategy”. This means that the company Z has at least two strategies, i.e. a business one, which focuses on the main objectives, and another one, which concerns corporate social responsibility, which in a way is a secondary area of focus.

“Strategic CSR” is a term used quite often recently not only in the academic literature but in practice as well. For Chinese researchers “Strategic CSR is the very type of CSR most firms are taking in the practice because the act of a firm’s social contribution is not only good for the society but also good for the investor’s long-term profitability and development” (Wenzhong and Yanfang 2017). Some researchers (Bocquet et al. 2017) are examining two types of CSR behavior: strategic and responsive, using the “strategic CSR model” described by Porter and Kramer (2006). In this approach CSR can deliver more business opportunities and innovations, enabling the firm to build competitive advantages through social progress, redesigning products, markets, and productivity in the value chain.

CSR strategies are usually constructed in the same way as business strategies, which means that they describe several important areas of focus, priorities, strategic objectives, actions and measures. Unfortunately, however, they are often similar in different companies, even from different industries. Even though it is understandable that certain elements—like important stakeholder groups—may overlap, the main strategic determinants should be the basis for building a unique position in the market. It is possible to determine the approach to corporate social responsibility based on the strategic documents of various companies as well as their CSR reports, although then we must acknowledge the fact that these reports are usually a bit “tailored” to the needs of company’s stakeholders. Moreover, such statements often suggest a holistic approach based on the integration of business strategy and CSR strategy, while practice and the examples given prove otherwise. For example, in the report of company XX (Rok 2013) three main objectives are given: portfolio development, expansion and the exploration of new business areas. These objectives are being pursued to ensure a stable income, long-term growth and a continuous improvement of the company’s value. In terms of CSR the mentioned report of XX also adds that “in Poland we observe a growing awareness that profits cannot be achieved without a credible dialogue with the social, environmental and economic environment. We also operate according to this idea”. Thus, we can see that the operational definition of CSR in this case includes only two elements: a dialogue with the stakeholders as a tool for strengthening the generated profits and an emphasis on three aspects of sustainable development, particularly within the context of risk management.

In corporate report of company YY (Rok 2013) we can read that “corporate social responsibility is a tool that should contribute to responsible company management, improve the image and credibility of the brand and, consequently, improve the financial results in the long term”. Here we have both the operational element concerning management systems and the social element focused on image. In another report of YY, 2 years later, the given statements are less ambiguous. The company mission is formulated as “maximising the benefits to society by providing services of the highest quality”, which clearly contains strategic objectives regarding the implementation of CSR priorities and ensures their operationalization through a clear CSR management structure covering all areas of functioning of the company YY.

The report of bank ZZ, as another example, states that “corporate social responsibility is inherent in the nature of our Bank, which with its activities makes a significant contribution to the economic, social and environmental development of the country”. Thus, for bank ZZ corporate social responsibility is—on the one hand—“an approach to the management of the organisation, which allows it to contribute to the sustainable development of society”, which is basically the core business activity resulting from the “nature” of the bank, and on the other hand, it assumes “going beyond the obligations required by law and caring for: ethical principles, building positive relationships with employees, the social environment and the natural environment” (compare article of Sułkowski and Fijałkowska in this book). Can we therefore assume, based on the information from the cited reports, that in these companies the operational definition of CSR is explicit enough to clearly formulate their priorities? It seems that it is not, after all. In recent reports from the global market the challenge with an operational definition of CSR is solved by replacing term CSR with sustainability, which is much better defined, integrating social, environmental and economic performance (Schaltegger and Wagner 2017).

3 Barriers to Sustainable Strategic Management Approach

From the point of view of management practitioners in Poland, corporate social responsibility is still predominantly formulated in a language that is inconsistent with modern strategic management, whether in the form of radical postulates of a social activism nature, or merely—moral obligations. Discussions about sustainability or CSR are too abstract or—on the contrary—too simplified, detached from the real challenges that arise in management here and now (Aluchna and Rok 2018). The main underlying factor is the low level of social trust, significantly hindering the development of the concept of CSR, which should predominantly consist in partnership and cooperation, allowing to determine the actual social responsibility, i.e. a participatory management model that considers the participation of various groups of stakeholders. Some positive outcomes can come with an ongoing expansion of The UN Sustainable Development Goals—the 17th Goal recognizes the importance of partnerships and collaborative governance but organizing large multi-stakeholder partnerships requires sophisticated implementation structures for ensuring collaborative action (MacDonald et al. 2018). Now we can observe an information chaos, where questionable knowledge combined with a fixed view of the economic reality become the basis for developing policies on corporate social responsibility by various companies, sometimes even acting in good faith. At best, the consequences are like after taking a placebo—neutral for the quality of management systems and social performance.

In the Polish market a systematic pursuit of implementing comprehensive systems of corporate social responsibility can be seen primarily in three groups of companies (Gasparski et al. 2010). The first group includes transnational companies considering the various aspects of corporate social responsibility, that in the global market are assessed both by investors and e.g. consumers or other stakeholders. Usually, after the first stage of development of CSR in the home market, such corporations are beginning to expect that their principal subsidiaries operating in other markets will implement the same guidelines for the management of various areas, as well as reporting that considers the globally adopted indicators. This group of companies on the Polish market is growing the fastest in terms of quality of CSR management, at first mainly influenced by the guidelines from their parent companies, and later often independently of these guidelines, once the business benefits of CSR become more obvious. Initially, however, the pressure clearly comes from the parent company (See article of Dancewicz in this book).

The second group of companies—smaller in terms of numbers—consists mainly of large and rapidly developing private companies with domestic financial capital. Typically, they begin to seek CSR solutions when they already have solid business partners who have implemented CSR standards in international markets and based on these standards have undertaken to verify their suppliers and other business partners in this regard. A similar situation occurs when such companies try to gain international business partners—sometimes also investment or financial partners—and within the framework of their future cooperation they must document not only the quality of their products, but also the quality of their management—that is, if those partners attach great importance to sustainability in the supply chain. In such cases, the pressure comes from business partners.

The third group primarily consists of the largest companies of the State Treasury, where the management is more sensitive to pressures of a political nature, especially coming from the European Commission within the framework of European economic policy, an increasingly important part of which are corporate sustainability, circular economy, social inclusion, etc. Often such companies are also motivated by the desire to improve their management standards, to be able to strongly emphasise that they match the international standards in their industry (See more in the article of Kacprzak in this book, Chap. 2).

Corporate sustainability is becoming a subject of discussion among managers in Poland in recent years, although this is a difficult discussion. Mainly because sustainability is a very vast subject and if it cannot be linked to actual examples from the life of the company, then the discussion becomes abstract. The emerging controversies in Poland around the term itself as well as the entire concept of CSR were caused by many reasons. The first important factor causing various controversies was the memory of our recent history, when all companies were, in a sense, “socially responsible” by definition. This term was and often still is associated with a return to the times of the discredited socialist, or as it is called today, communist economy (See also article of Rojek-Nowosielska in this book). At the same time, however, being aware of the evaluative nature of the term “corporate social responsibility”, the representatives of most companies eagerly began using this term, although they claimed that the essence of the social responsibility undertaken by their business is primarily compliance with the law and concern for economic performance. Therefore, respondents more strongly identified themselves with the vision of a business where the social consequences of the core business activity are indeed acknowledged, but no additional, voluntary commitments of a social or environmental nature are made (Rok 2013).

The second factor that is specific to the Polish market, affecting the emerging controversies, is mainly associated with the difficulties in defining the various positive effects of corporate sustainability or strategic responsibility. The acknowledged measures of success still primarily include financial indicators, rather than long-term benefits for the natural environment, for employees or the local community. One can think that failing to see the relationship between the growth of social welfare, combating climate change and company performance is caused to a certain extend by the fact that even the managers of the largest companies are convinced that social results or social benefits resulting from company activity cannot be measured. That is why dealing with corporate responsibility is often entrusted to the staff of communications departments, who often use simple indicators and in addition to the incurred expenditures they report the number of positive press coverage. The result is a kind of “vicious circle” that strengthens managers in their belief that corporate responsibility only means costs that need to be borne to build an image and no strategic reorientation of management priorities is needed here. More research in this field is necessary, using methodologies specific for psychological or sociological inquiry.

The applied CSR rhetoric often has little to do with the real social or environmental challenges associated with the conducted business activity. But some practitioners from business are putting already important questions during MBA courses or different trainings: How can strategic priorities in terms of CSR be pursued, to maximise the benefits for both the company and society at the same time? How should managers and other employees be trained in order for them to respond adequately to the changing social and environmental expectations? How should CSR be managed to effectively build a competitive advantage on the global market? That is why it is important to set new frameworks for the strategic approach to corporate responsibility.

Managers have been intuitively recognizing that the integration of corporate responsibility and sustainability is an important topic, but they just rarely consider it in strategic management. In the academic literature corporate sustainability goes beyond corporate growth and profitability and includes a firm’s contribution to societal goals, environmental protection, social justice and equity, and economic development (Schwartz and Carroll 2008). Considering corporate sustainability or strategic responsibility in business strategies and processes has become recently a promising way to cope with the global challenges on the market (Bhattacharyya 2010; Hahn et al. 2017) under the label of strategic sustainable management or “sustainable strategic management” (Rego et al. 2017). Since decisions related to corporate sustainability are taken at a strategic level, which is essential for generating a sufficient level of company-wide commitment, there has also been increased interest in the subject related to the possible integration of corporate sustainability in a company’s strategy.

There is still a lack of empirical—quantitative and qualitative—studies on the integration of corporate sustainability into strategic management (Engert et al. 2016). Some conceptual papers are discussing different options and motivations behind implementing sustainability into the corporate strategy. Different options are considered: to adjust the corporate strategy to include objectives regarding economic, ecological and social performance; to define a specific sustainability strategy as part of the corporate strategy; or to redefine the corporate strategy based on the premise of creating a sustainable strategic management system (Oertwig et al. 2017).

4 Materiality Matrix: A Tool for Aligning Corporate Sustainability with Business Strategy

Corporate responsibility approach is implemented primarily by larger enterprises once certain choices have already been made, such as the selection of a market domain. Therefore, the important question is whether CSR can lead to the need to modify or even significantly change the business strategy. The CSR concept clearly defines this change: striving to optimise the value for all stakeholders. Companies that implement corporate responsibility have various ways of formulating their business goals, but often they refer to—at least in the global market—creating stakeholder value, shared value or sustainable value. Its basis is the principle formulated by C. Laszlo, among others: “sustainable value occurs only when a company delivers it to shareholders while not destroying value for other stakeholders” (Laszlo 2003). Corporate sustainability is conducting business with a long-term goal of maintaining the well-being of the economy, environment and society.

From a stakeholder perspective, a company’s activities cannot be seen only in terms of value creation for that company, but also in terms of sharing that value between various stakeholder groups and consequently achieving an adequate level of consistency. Creating sustainable value means accepting a commitment describing a specific vision of the desired future that the company strives for by merging the company’s superior shareholder value with stakeholder value. In the management practice of sustainable companies, value optimisation is often based on Freeman’s stakeholder strategy matrix (Freeman et al. 2007), or on other similar tools, such as an assessment map of the company impact on stakeholders and shareholders (Laszlo 2003). Prioritisation is an important element influencing the formulated strategic objectives and it relies heavily on the various results achieved in the process of involving stakeholders.

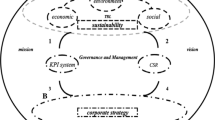

The degree to which stakeholder expectations are considered is a very important business issue, although it often comes down to identifying the strength of individual stakeholders and the potential threats to company activities—thus, it is considered in terms of risk management. The materiality matrix balancing relevance for shareholders and other stakeholders can be defined in a variety of ways (Fig. 1), particularly when it comes to the actual practice of developing or modifying a strategy, rather than just some acceptable, usually simplified, form that can then be presented in a public CSR report.

For example, on the shareholder axis, instead of the traditional business case-based approach, i.e. the profitability for the company, measures are used that refer to the significance of the economic, environmental and social—including long-term—impacts, level of importance for company sustainability success, or relevance from external stakeholders’ point of view. On the axis of other stakeholders also certain changes are introduced, going from a typically reputational approach, when we determine the impact on the assessment made by stakeholders, to an assessment of the importance attached to the objectives and the resulting future actions that can be undertaken by the stakeholders, and ending with the relevance of the actual challenges concerning various aspects of sustainable development. The materiality matrix (see Fig. 1) for strategic priorities allows to focus on the area that is essential both for shareholders and stakeholders, e.g. primarily undertaking actions that concern the most important forms of company impact on the natural and social environment, while also responding to the greatest challenges of sustainable development.

Therefore, in companies where the conclusions gathered in the process of dialogue with stakeholders serve not only to assess the CSR strategy or the undertaken measures, but also to introduce possible changes in the business strategy, a properly used materiality matrix can be a useful tool.

Sustainability issues of particular significance are initially selected based on GRI reporting standard and its own sustainability themes. After comprehensive review made in the process of stakeholder dialogue, internal and external, with the active participation of top managers from all business units, the matrix can be build, with a clear and proper assignment of issues to the particular part of the matrix: A, B, C, D. The materiality of each of selected issues—concerning for example sustainability in the supply chain, environmental aspects in production, social aspects in operations, sustainable products delivering—should be scored and plotted in the materiality matrix, using two scales representing importance to business and importance to stakeholders. To implement real sustainability strategy company is starting from the A part—high impact on business and high impact on stakeholders.

This process also contributes to strengthening the organisational learning process, and even if at a given stage, for whatever reason, not all challenges can be addressed, it is important to be aware of the relevance and to know the long-term approach. This is also an important factor in shaping the motivations of company leaders, resulting in a broadened perspective and a subsequent transformation of the organisational culture recognising the importance of the company taking on sustainability challenges. When reconstructing this approach, several elements need to be focused on that are important in the process of creating business and social value simultaneously.

The starting point is usually the identification of a significant social challenge, which in the perspective of further company development—if not taken on—could be a significant barrier to e.g. increasing sales in the future. We are not talking about purely market challenges here, but about those that concern broadly understood sustainable development, i.e. a desired state of equilibrium that ensures a socio-economic and environmental order, justice between generations and within generations. Such challenges are often the focus of attention of both the external and internal stakeholders of a company. They may be due to demographic trends (e.g. aging population, which may indicate the need to adapt the manufactured products to the future expectations of the growing social group of seniors) or current events affecting possible changes in customer attitudes (e.g. criticism of aggressive marketing of financial products). While it is often claimed that CSR is a response to stakeholder expectations, what matters is to what extent the expectations “fit in” with trends, important topics and events. It is also important to what extent managers can predict probable future expectations, not yet expressed directly. That is why at this stage it is important to provide a clear answer to the following question: why is this challenge important to the company development?

The second element of the presented model is the decision-making process resulting from a certain type of perception and motivation. The “change agents” are often CSR managers, provided that their position within the organisational structure allows them to influence important business decisions. This is also dependent on the market domain and the challenge itself that has been identified—some challenges are easier to recognise as very important both for society and for the company (e.g. e-education), others seem unrealistic (e.g. reducing global hunger). Decision-making can be influenced by how others perceive the alignment with the company strategy or code of values, the benefits of compliance with “soft regulations”, the possibility for further developing an existing product or programme, profitability, moral and social norms, trends and political correctness, enhancing employee loyalty or achieving individual goals. At this stage, the main question is: what do we want to achieve with this challenge?

The third element is the answer to the question: what exactly do we do and how do we do it? Here it is important to develop a coherent business strategy, to define how to achieve the planned goals. This strategy can be linked to the strategy of corporate sustainability—if the company has one. The bottom line is to plan the necessary resources, implementation tools, and indicators for measuring the business results in relation to the expectations and the set goals. Thus, we are evaluating the effectiveness, i.e. the ratio of effort to results. It is from the point of view of effectiveness that innovative solutions such as partnerships with NGOs or public organisations are considered at this stage to increase the chances of reaching the target group while minimising costs.

The last element of this model is measuring the impact, i.e. finding the answer to the question: how do we know that this benefited the target social groups? Impact indicators should be specific and measurable, where possible, and not in the form of e.g. “overall increase in the quality of life of the inhabitants of the region”. The impact can be indirect or direct, achieved in the short or long term, it may concern economic factors (e.g. the creation of high quality jobs in the region), environmental factors (e.g. a reduction of the total emissions of pollutants at city level), or social factors (e.g. increased availability of selected products for marginalised groups).

Impact measurement is a rapidly developing new reporting area, one that is very important for increasing sustainable value (Crane et al. 2017). With these types of projects, it is not just about business results—or at least no loss—but it is also about an attempt to assess the actual contribution to reducing a given social problem, e.g. whether the introduced innovative service for previously marginalised people has reduced the scale of exclusion in the target group. Achieving measurable success motivates to broaden the scope of activity, to modify important tools and to maintain such projects in the long run. Thus, it allows for effective operationalization while gaining new allies among the management staff. Because nothing persuades managers better than effectiveness—also in terms of solving social problems using business methods.

5 Strategic Challenges for Sustainability

The well-known strategic management scholar K. Obloj points out that every change in strategy must be linked to changes at the level of four essential processes: understanding and interpreting the business environment, setting goals, defining company boundaries, and building a business model (Obloj 2010). In all these processes it is necessary to broaden the perspective, primarily to understand the market challenges related to the changing environment in the context of sustainable development, and to formulate or change the strategic objectives and the business model. If we were to transfer these considerations to a more general level, we would be dealing with a certain broadening of the strategic perspective in the direction of corporate sustainability strategy. The management executives in companies that implement corporate responsibility should assume a broader perspective at the stage of interpretation and giving meaning to changes, sense-making. Based on, among other things, the conclusions drawn from an analysis of the materiality matrix as well as a PESTLEE strategic analysis, which considers political, economic, social, technological, legal, environmental and ethical factors, they focus primarily on the most important sustainability challenges that may be relevant to the company’s further development.

The starting point in this process is to identify and propose business solutions to—or ways to at least contribute to some extent to minimising—significant challenges in the environment, rather than just trying to understand trends that we have no influence on anyway. This makes it possible to create real value for shareholders and at the same time for other stakeholders, creating a set of complementary goals that allow for the sustainability or optimisation of value for all stakeholders. This, in turn, should be ensured by an adequate business model, enabling sustainability innovation, e.g. for the efficient, economic and ethical use of material and non-material resources. That is why not only the assessment indicators of the key financial results (KPIs—key performance indicators) are important here, but also indicators of economic, social and environmental impact (key impact indicators). And finally, in terms of defining the boundaries of a company, broadening the perspective involves answering the question about the limits of corporate responsibility, i.e. what we take responsibility for and what we do not. It is pointed out more and more often that the boundaries of a company do not coincide with the boundaries of responsibility.

In practice it can hardly be expected that consciously implementing corporate responsibility in a radical way, virtually overnight, will lead to a significant change in priorities at company level, or will cause a significant change in the company strategy, leading to a full merger of business and social goals. The experience in implementing the principles of corporate responsibility and sustainability as an important management dimension in major companies shows that the changes are permanent and based on the continuous improvements, not incremental ones. Sustainable strategic management requires an accurate diagnosis conducted by senior managers regarding the organisation itself and its environment. The uncertainty and unpredictability of changes in the technological, economic or political environment cause an increased emphasis on flexibility and the ability to respond quickly to social expectations.

However, broadening the perspective in the process of developing an integrated business strategy contributes to several important changes, above all at the business model level, especially in the case of new ventures. A business model that incorporates CSR principles is a form of organisational innovation, truly provides value for shareholders and other stakeholders at the same time (Schaltegger et al. 2016). From a strategic perspective this means that this type of innovation of the business model should lead to creating a competitive advantage through a higher value for the customer, contributing to sustainable development at both the level of the company and of society.

6 Conclusion: Managing as if CSR Mattered

CSR is not just a form of doing good deeds and not just a better way to maximise profits, but rather a growing awareness that the role of business in society is not just about benefiting business owners or shareholders. If there is the belief that the sole purpose of companies is to maximise profit for shareholders, CSR will only be implemented once it is proven that it is a tool for cost reduction (e.g. access to capital) or better risk management. It is still the case in Poland, where companies lack a strategic approach with respect to corporate sustainability integration. Adopting a broader perspective, i.e. considering not only financial performance but also social and environmental results—with the belief that business also creates environmental and social value—leads to the search for justifications based on elements of competitive positioning, such as building new brand attributes and gaining new markets.

It is worth noting that corporate responsibility is formed in a process of dialogue. By collaborating with stakeholders and establishing, through a process of dialogue, the significant areas of responsibility and main sustainability challenges, an organisation could expand its ability to create its own future in the best possible way. Active stakeholder engagement would also make it possible to address the changing context of the functioning of a company, to define the scope that is consistent with materiality matrix. Companies cannot co-create sustainable value without an active cooperation, because competitiveness requirements make cooperation necessary. In other words, the development and the growth of value of a responsible company should translate into increased satisfaction and quality of life for all stakeholders.

It can be assumed that discussions about corporate responsibility are in principle a form of response to one of the most important dilemmas in management theory as well as in business ethics. Does the only role of business come down to effectively engaging resources to maximise profits, without violating the law, or is the role of business much broader nowadays, primarily consisting in looking for sustainable solutions that are beneficial to all stakeholders? If we assume that the role of business is to create sustainable value, then we can say that corporate responsibility is becoming a theory of corporate ethics, while the practice of sustainability consists in finding the best ways to build a dynamic equilibrium in the time and space of stakeholders. This approach is about finding a balance in the economic, social and environmental dimensions, in relationships with current stakeholders, but also in the process of protecting and developing the resources needed in the future. The main pillar of this approach is sustainable strategic management system and the whole process of integrating business strategy with sustainability strategy.

For companies operating on the Polish market it is the biggest challenge for next few years. There are some pioneers in this field already, mostly among multinational companies (Compare article by Dancewicz in this book). But it is also the biggest challenge for the strategic management scholars—the new research area devoted to real integration of sustainability into business decisions is not well defined yet. Further steps in this area of sustainable strategic management framework are nevertheless needed to extend the scope towards integrated management systems to evaluate and control the sustainability performance of companies. Overall, the new approach to sustainability management clarifies the interplay between classical business strategy and corporate responsibility and highlights the opportunity for future development not only on the Polish market.

References

Agle, R. B., Donaldson, T., Freeman, R. E., Jensen, M. C., Mitchell, R. K., & Wood, D. J. (2008). Dialogue: Toward superior stakeholder theory. Business Ethics Quarterly, 18(2), 153–190.

Aluchna, M., & Rok, B. (2018). Sustainable business models: The case of collaborative economy. In L. Moratis, F. Melissen, & S. O. Idowu (Eds.), Sustainable business models: Principles, promise, and practice (pp 41–62). Cham: Springer.

Avery, G. (2017). Top leaders shift their thinking on corporate social responsibility. Strategy & Leadership, 45(3), 45–46.

Banerjee, S. B. (2008). Corporate social responsibility: The good, the bad and the ugly. Critical Sociology, 34(1), 51–79.

Bhattacharyya, S. S. (2010). Exploring the concept of strategic corporate social responsibility for an integrated perspective. European Business Review, 22(1), 82–101.

Bocquet, R., Le Bas, C., Mothe, C., & Poussing, N. (2017). CSR, innovation, and firm performance in sluggish growth contexts: A firm-level empirical analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 146(1), 241–254.

Bove, A., & Empson, E. M. (2013). An irreconcilable crisis? The paradoxes of strategic operational optimization and the antinomies of counter-crisis ethics. Business Ethics: A European Review, 22(1), 68–85.

Brooks, C., & Oikonomou, I. (2018, January). The effects of environmental, social and governance disclosures and performance on firm value: A review of the literature in accounting and finance. The British Accounting Review, 50(1), 1–15.

Ceglinski, P., & Wisniewska, A. (2017). CSR as a source of competitive advantage: The case study of Polpharma group. Journal of Corporate Responsibility and Leadership, 3(4), 9–25.

Crane, A., McWilliams, A., Matten, D., Moon, J., & Siegel, D. S. (2008). The oxford handbook of corporate social responsibility. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Crane, A., Henriques, I., Husted, B. W., & Matten, D. (2017). Measuring corporate social responsibility and impact: Enhancing quantitative research design and methods in business and society research. Business & Society, 56(6), 787–795.

Engert, S., Rauter, R., & Baumgartner, R. J. (2016). Exploring the integration of corporate sustainability into strategic management: A literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 112, 2833–2850.

Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., & Wicks, A. C. (2007). Managing for stakeholders: Survival, reputation, and success. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Gasparski, W., Lewicka-Strzałecka, A., Rok, B., & Bąk, D. (2010). In search for a new balance: The ethical dimension of the crisis. In B. Fryzel & P. H. Dembinski (Eds.), The role of large enterprises in democracy and society (pp. 189–206). Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan Ltd.

Hahn, T., Figge, F., Aragón-Correa, J. A., & Sharma, S. (2017). Advancing research on corporate sustainability: Off to pastures new or back to the roots? Business & Society, 56(2), 155–185.

Husted, B. W., Allen, D. B., & Kock, N. (2015). Value creation through social strategy. Business & Society, 54(2), 147–186.

Kolk, A., Kourula, A., & Pisani, N. (2017). Multinational enterprises and the sustainable development goals: What do we know and how to proceed? Transnational Corporations, 24(3), 9–32.

Laszlo, C. (2003). The sustainable company: How to create lasting value through social and environmental performance. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Les, E. (2001). Zarys historii dobroczynnosci i filantropii w Polsce. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Proszyński i S-ka.

MacDonald, A., Clarke, A., Huang, L., Roseland, M., & Seitanidi, M. M. (2018). Multi-stakeholder Partnerships (SDG# 17) as a means of achieving sustainable communities and cities (SDG# 11). In Handbook of sustainability science and research (pp. 193–209). Cham: Springer.

Obloj, K. (2010). Pasja i dyscyplina strategii. Jak z marzen i decyzji zbudowac sukces firmy. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Poltext.

Oertwig, N., et al. (2017). Integration of sustainability into the corporate strategy. In R. Stark, G. Seliger, & J. Bonvoisin (Eds.), Sustainable manufacturing: Sustainable production, life cycle engineering and management (pp. 175-200). Cham: Springer.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2006). The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 78–92.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2011). Creating shared value: How to reinvent capitalism – and unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harvard Business Review, 89(1–2), 62–77.

Rego, A., Cunha, M. P., & Polónia, D. (2017). Corporate sustainability: A view from the top. Journal of Business Ethics, 143(1), 133–157.

Rok, B. (2000). Odpowiedzialnosc spoleczna w zarzadzaniu. Personel i Zarzadzanie, 22, 7–11.

Rok, B. (2013). Podstawy odpowiedzialnosci spolecznej w zarzadzaniu. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Poltext.

Schaltegger, S., & Wagner, M. (Eds.). (2017). Managing the business case for sustainability: The integration of social, environmental and economic performance. London: Routledge.

Schaltegger, S., Hansen, E. G., & Lüdeke-Freund, F. (2016). Business models for sustainability: Origins, present research, and future avenues. Organization and the Environment, 29, 3–10.

Schwartz, M. S., & Carroll, A. B. (2008). Integrating and unifying competing and complementary frameworks: The search for a common core in the business and society field. Business & Society, 47(2), 148–186.

Wenzhong, Z., & Yanfang, Z. (2017). Research on ethical problems of Chinese food firms and implications for ethical education based on strategic CSR. Archives of Business Research, 5(7), 76–84.

Yin, J., & Jamali, D. (2016). Strategic corporate social responsibility of multinational companies subsidiaries in emerging markets: Evidence from China. Long Range Planning, 49(5), 541–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2015.12.024.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rok, B. (2019). Transition from Corporate Responsibility to Sustainable Strategic Management. In: Długopolska-Mikonowicz, A., Przytuła, S., Stehr, C. (eds) Corporate Social Responsibility in Poland. CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00440-8_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00440-8_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-00439-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-00440-8

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)