Abstract

Contextual reference is made to the broad sociopolitical profile of this enormous archipelago and the basic parameters of adolescent fertility, age of first intercourse, marriage patterns, contraceptive use, and levels of education. It is noted that while adolescent pregnancy outside marriage is relatively low compared with many other countries, medical authorities have long been concerned with the range of health consequences it has for young mothers. The chapter then goes on to explore youth sexual culture in more depth with reference to cultural norms and values, and recently, primarily qualitative research findings that provide a rich insight into Indonesian (particularly Javanese) youth’s experience of premarital sexual relationships and the personal interaction that regulates premarital intercourse. For instance, adolescent pregnancy is very common in Indonesia, but only considered to be a social problem by the general populace in those relatively rare instances where it takes place outside marriage. In contrast, there has long been great concern within Indonesian medical circles with a range of medical consequences associated with (such primarily marital) adolescent pregnancy and the political obstacles that prevent health practitioners from addressing the sexual and reproductive health (SRH) needs of unmarried adolescents. The final section reviews the wide range of educational and health initiatives that have been developed to address adolescent sexual and reproductive health in Indonesia. The key themes that run through this review are the highly cultural contested nature of sexual matters in Indonesia, the widening of debate and pluralization of youth sexual lifestyles attendant to social change, the recent political liberalization, and the continuing paralysis of implementation of widespread effective education and health services to enhance adolescent reproductive and sexual health.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Indonesia: adolescent pregnancy

- Cohabitation

- Contraception

- Informal sexual information

- Low female status

- Maternal morbidity

- Postpartum fecundability

- Premarital sex

- Sexual and reproductive health

- Sociocultural context

- Virginity

- Youth sexual culture

Introduction

Adolescent pregnancy is very common in Indonesia, but only considered to be a social problem by the general populace in those relatively rare instances where it takes place outside marriage. In contrast, there has long been great concern within Indonesian medical circles with a range of medical consequences associated with (such primarily marital) adolescent pregnancy and the political obstacles that prevent health practitioners from addressing the sexual and reproductive health (SRH) needs of unmarried adolescents.

We structure this chapter in terms of four broad sections: firstly, an introduction to the profile of this enormous archipelago; secondly, a contextual review of some of the basic parameters of adolescent fertility, marriage patterns, age of first intercourse, contraceptive use, and educational levels; thirdly, an elaboration of the youth sexual culture that shapes the nature of adolescent pregnancy in Indonesia; and fourthly, a concluding discussion of the nature of, and obstacles to, appropriate contraceptive service provision for adolescents. Throughout the chapter, we seek to shed light on these processes and debates by recurrent reference to the key themes of Indonesian culture and policy. Thus, the chapter seeks to move from context, to a richer exploration of sexual lifestyles, and to policies and programs that seek to enhance youth SRH in Indonesia.

Profile of Indonesia

The Republic of Indonesia encompasses an archipelago stretching along the equator, which consists of approximately 17,000 islands, with a total population now over 236 million, and located between Asia and Australia. There are five major islands: Sumatera in the west; Java in the south; Kalimantan and Sulawesi in the middle running along the equator, and Papua on the east bordering New Guinea. Other important islands include Maluku in the north, and Bali and Nusa Tenggara in the south. The Indonesian archipelago forms a part of the ‘Pacific Ring of Fire,’ which is prone to earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions. A tsunami in December 2004 killed more than 150,000 people in Indonesia, with most casualties in the province of Aceh.

Indonesia is the fourth most populous country in the world, with around 300 ethnic groups; approximately 45 % of the population are Javanese, 14 % Sundanese, 7.5 % Madurese, 7.5 % Coastal Malays, and 26 % classified as others. The large number of islands and the variety of ethnic groups with their own local languages across such a wide area has given rise to a diverse culture that the country recognizes in the national motto of ‘Unity in Diversity’ (CBS and Macro-International 2008a). The national ideology of Pancasila, which seeks to foster national integration, explicitly expresses the goals of toleration, diversity, and plurality. However, unfortunately outbursts of ethnic and religious conflict and violence have occurred in particular localities (Vatikiotis 1994).

Indonesia has experienced several political shifts since proclaiming its independence in 1945 and has also faced several political problems caused by ideological, ethnic, and racial differences. The first political period under Suharto was characterized by considerable political conflict and deepening economic stagnation (Fryer 1970). When a new era began with the establishment of the New Order government in 1965, Indonesia made substantial progress, particularly in stabilizing political and economic conditions (Vatikiotis 1994; CBS and Macro-International 2008a).

In 1998, Indonesia entered its worst economic crisis since its independence, when the economic growth rate dropped to minus 13 % (CBS and Macro-International 2003) and the political situation become unstable in several regions. During this period, the highly centralized New Order regime collapsed and was replaced by the recent and continuing Reform Era. For the first time in Indonesia’s history, the president was elected directly through general election in 2004. At the same time, based on Law No. 22 1999, decentralization to regional government was enacted by giving fuller autonomy to the district (municipalities and districts) level. With some limited exceptions, the local government has responsibility for all decentralized central government ministries at provincial and district levels. In line with this change of paradigm from centralized to decentralized government, family planning affairs have also been handed over to district government. The fundamental change of political paradigm has also been made by the National Family Planning Coordinating Board (BKKBN) at central level to reformulate their strategic management, and vision and mission (CBS and Macro-International 2008a).

According to the Basic Health Survey of 2009 (Ministry of Health 2009), the population of Indonesia was about 236 million with a population growth rate that has declined from 1.98 % between 1980 and 1990 to 1.49 % between 1990 and 2000. It is projected to decline further between 2000 and 2010. It was also estimated that 42 % of the population lived in urban areas and 58 % in rural areas (CBS 2002). Almost 59 % of the total population lives in Java, which covers only 7 % of Indonesia’s total land area. In contrast for instance, only around 1 % of the country’s population lives in Papua, which makes up approximately 19 % of the total land area of Indonesia (CBS and Macro-International 2008a).

In terms of population structure, there were more than 30 million people aged 10–24 years. Adolescents (10–19 years old) comprise 19.3 % of Indonesia’s population, with adolescent boys accounting for 19.9 % and adolescent girls for 18.8 %. The Indonesia Demographic Health Survey (IDHS) 2007 shows that Indonesia is in a demographic transition from a younger to an older-aged population structure (CBS and Macro-International 2008a). The proportion of the population below the age of 20 has decreased from 51.9 % in 1970 to 38.5 % in 2005. Simultaneously, the population above 60 years has increased from 5.2 % in 1970 to 7.3 % in 2005. Changes in the age structure result mainly from a decline in fertility rates. Findings from 2002 to 2003 of IDHS indicate that there has been a steady decline in fertility from 5.6 children per woman in 1970 to 3 in 1991 to 2.6 per women in 2001–2002 (CBS and Macro-International 2008a).

Although 85 % of the Indonesian population is Muslim (the largest Muslim population in the world), it is not a ‘fundamentalist’ Muslim country (Arkoun 2003; Masqood 1994). It has a much more tolerant form of Islam than is found in many other parts of the Muslim world (Hefner 2002). However, Islamic values and teaching have an important place in the lives of many of its people (Ford et al. 1997). Many people combine their formal Islamic identity with a range of practices and beliefs drawn in different parts of the archipelago from for instance, animism, mysticism, and meditational disciplines. The remainder of the Indonesian population are primarily Christian, but with smaller proportions from other religions. Javanese in particular take pride in their cultural traditions of self-control and tolerance and preserve a strong social hierarchy through both their behavior and language (Hull et al. 1977). These cultural tendencies are further elaborated below with reference to their influence on the expressions of Javanese youth sexual culture (Fig. 1).

The Broad Context of Indonesian Policy to Address Adolescent Pregnancy

In terms of adolescent pregnancy, Indonesia’s concerns with fertility are intertwined with a whole list of associated social and health consequences, such as unwanted pregnancy, maternal mortality and morbidity, abortion, and STDs (including HIV/AIDS). The government of Indonesia has faced great difficulty in attempting to develop programs and policies to deal with the reality of SRH problems, particularly those for young people (Utomo 2002). Although the government has started to provide SRH information to young people, it is more commonly in response to concerns about HIV/AIDS, rather than unwanted pregnancy or unsafe abortion (Utomo 2003). The major criticism of such programs is that they only run sporadically and reach only small numbers of young people. The SRH needs of unmarried young people have been largely ignored by existing health services (Utomo 2003).

There is much debate within Indonesia concerning the most effective socially and culturally desirable SRH education and services for young people (Ford and Siregar 1998). The diverging perspectives between what may be described as ‘moralistic’ and ‘pragmatic’ groups often impede the implementation of youth SRH programs (Ford and Siregar 1998). Conservative perspectives argue that premarital sexual activity is simply socially unacceptable and that unmarried young people should not be provided or ‘contaminated’ with sexual health education, because it is believed that such education programs lead to increased sexual activity among young people. The liberal view in Indonesia argues that while premarital sexual activity is not necessarily socially desirable, it nevertheless does take place, and needs to be properly addressed by health and educational services (Ford and Siregar 1998). There are many informal sources of sexual information and images, including films and pornographic materials, which are easily accessible to young people in Indonesia. However, this information is often designed to stimulate and titillate rather than educate young people on sexual matters (Jones 2001).

As noted above, Indonesia is currently undergoing a radical transition through tumultuous changes toward greater social openness and debate, concomitant to the fall of the authoritarian ‘New Order’ in 1997. The current relaxation of censorship and control provides the opportunity for more open expression between conservative and liberal Islamic groups in a contestation of sexuality. While more liberal sexualized images and literature are becoming available in the Indonesian media, conservative groups have hit back, for instance in criticism of supposedly erotic dangdut dance/music and the publication of the controversial ‘Playboy’ magazine, even though the Indonesian version is less explicit than the original. The recently passed anti-pornography law has been used to attack public figures accused of placing video sex scenes over the Internet to the public recently (Dipa 2011).

Prior to a fuller discussion of the wider sociocultural context related to adolescent pregnancy, it is important to discuss some aspects related to pregnancy among the young, including adolescent fertility, proximate determinants of fertility, changes in marriage patterns, estimates of premarital intercourse, contraception use, premarital pregnancy, and abortion.

Adolescent Fertility/Pregnancy

The issue of adolescent fertility is of course important for a range of health and social reasons. Adolescent childbearing has well recognized potentially negative demographic and social consequences (Blum 1991). Children born to very young mothers face increased risk of illness and death (CBS and Macro-International 2008a). Adolescent mothers, especially those under aged 18, are more likely to experience adverse pregnancy outcomes and maternity-related morbidity and mortality than more mature women. In addition, early childbearing limits an adolescent’s ability to pursue educational opportunities (CBS and Macro-International 2008a).

It is important to note that although Indonesia has been fairly successful in reducing total fertility, much more limited progress has been made in addressing maternal mortality. Furthermore, short of mortality, there is a much greater problem of maternal morbidity that blights the lives of many women of poor backgrounds in Indonesia. Siregar’s study of maternal morbidity in West Java showed that such health vulnerabilities were strongly associated with a young age of pregnancy, poor nutrition and associated anemia, and low female status within the conjugal unit (Siregar 1999) (Tables 1, 2, 3).

Age of first marriage and intercourse are generally used as proxy measures for the beginning of exposure to the risk of pregnancy. The Indonesian Demographic and Health Survey (IDHS) 2007 has collected information on the timing of first sexual intercourse for women and men (CBS and Macro-International 2008a). The IDHS 2007 shows that data of age at first intercourse was not so different from age at first marriage, as age at initiation of sexual intercourse coincides with marriage. In Indonesia, marriage is closely associated with fertility because the overwhelming majority of births occur within marriage (CBS and Macro-International 2008a). However, since premarital sex is considered socially unacceptable, there may be a lack of accurate data available on, and possible underestimation of the proportions of women and men who engage in sexual activity before, and later, outside of marriage. Teenagers who have never married are assumed to have had no pregnancies and no births (CBS and Macro-International 2008a).

The IDHS 2007 data also show that 9 % of Indonesian women aged 15–19 have begun their childbearing. Compared with the results of the IDHS 2002 survey, there has been only a small decline in the proportion of adolescents who have begun childbearing, from 10 % to the current level of 9 %. It shows that the level of early childbearing is still substantial in Indonesia particularly in rural areas. There is an inverse relationship between early childbearing and educational and socioeconomic levels in Indonesia (CBS and Macro-International 2008a). The delay of first birth as a result of an increase in the age at marriage has contributed to a decline in fertility. The median age at first birth has increased from 20.4 for women 45–49 to 22.5 years at women age 25–29, indicating this gradual change (CBS and Macro-International 2008a).

Proximate Determinants of Fertility

Bongaart’s proximate determinants model TFR = Cm × Cc × Ca × Ci (Bongaarts and Porter 1983) was used to estimate the relative importance of key factors contributing to fertility decline in Indonesia. The impact of the indices for marriage, contraception, and postpartum fecundability were estimated, respectively.

The model was used with (potentially maximum) total fecundity (TF) average of 15.3 and the Indonesian TFR of 2.6 in 2007. The index of abortion in the model was set at 1.0–0.5 due to lack of data availability as recommended by Bongaarts and Porter (1983) for the countries with TFR less than three. This result indicated that the estimated contraceptive index (Cc) was 0.45 therefore contraceptive use has had the highest role in reducing the effect of fertility in Indonesia by 55 %. This confirms that the major determinant of fertility in modern times in Indonesia is the use of contraception to regulate fertility since Indonesia has officially accepted nationwide family planning since 1970.

Based on the results of IDHS in 2007, the age-specific proportion of married females was counted as 0.72 and age-specific marital fertility counted as 2.4 × 103, thus the estimated index of marriage (Cm) was 0.865, indicating that the inhibiting effect of (non and delayed) marriage on fertility is 13 %. The contribution of the index of marriage on fertility was due to delayed entry of women into marriage due to acquisition of higher level of education.

In terms of the index of postpartum infecundability (Ci), IDHS 2007 data showed that the mean duration of breastfeeding is estimated to be six months. The estimate index of postpartum infecundability (Ci) is 0.84, which means the contribution of postpartum infecundability in reducing fertility due to breastfeeding is 16 %.

Changes in Marriage Patterns

Given that most adolescent pregnancy in Indonesia takes place within marriage, it is important to review the recent trends in marriage. As in every country of Asia, both men and women are marrying later than they did in the past (Cleland and Hobcraft 2011). However, the rise of age at marriage in Indonesia has been less obvious than in many other countries (Jones 2001). In particular, in some rural areas people still favor early marriage and relatively large numbers of children. Jones (2001) found that age at marriage for females has traditionally been very young, especially in rural areas of West Java and among the Madurese population of East Java. In the past, some of the reasons for acceptance of early marriage and births of many children were the need for sharing the burden of taking care of their parents when these parents had become elderly; and the need for contributing toward the family income and welfare. So a high value was placed on the status of being married and negative value on the status of being single (Achmad et al. 1999). In such traditional settings in Indonesia, a girl who is not yet married after reaching a certain age (for instance age 16) will be derogatively referred to as an ‘old maid,’ encouraging some parents to ‘marry off’ their daughters at very early ages. Although a very young age at marriage for females still characterizes certain ethnic groups and geographic regions of Indonesia, in all cases the median age is rising (Jones 2001).

IDHS 2007 data show there has been substantial change in the age of marriage for women. The data show that 19 % of women aged 45–49 married at age 15 were compared with 9 % of women aged 30–34, and less than 7 % of women aged 20–24 were married by that age. Nevertheless, there continues to be a relatively substantial number (2 %) of women aged 15–19 who were married by aged 15. The National Basic Health Survey 2010 results also show that early marriage (under aged 20) of women is still high (4.8 % of aged 10–14 and 41.9 % of aged 15–19) especially among rural areas in some provinces in Indonesia. In general, urban women marry more than two years later than rural women (21.3 years compared with 18.7 years). Age of first marriage also increases with level of education and socioeconomic status of the family (CBS and Macro-International 2008a).

Some studies also show that there has been a strong positive association between education and age at marriage for females. In West Java, the economic and cultural changes among this previously early marrying population have led to a quite rapid rise in female age at marriage. Young village women nowadays are frequently employed in factories well away from their homes, traveling daily to this work (Jones 2001). In one recent study, 90 % of such factory women stated that they had the right to marry the man they loved as long as their parents agreed, and all said that marrying under the age of 20 was bad for women (Jones 2001).

People living in urban areas and with higher levels of education are much more receptive to proven scientific findings (for instance regarding health) and outside influences (good and bad) as compared to those living in rural areas. They believe that children now are costly commodities because providing for their food, clothing, school fees, and other school-related costs is expensive. The Javanese context is particularly interesting because historically both women’s position and marriage pattern have been somewhat distinctive. Javanese society traditionally has incorporated some major bases of power and independence for women, including economic participation, property rights, and a matrifocal bias in relationships and residence. Culturally, women are considered clever, good financial managers, and equal economic partners in marriage (Malhotra 1997).

Marriage in Java has traditionally been initiated by parents and takes place at early ages for both genders, but more so for women. Since the 1960s, Javanese marriage patterns have changed more with respect to marriage arrangements and divorce patterns than with respect to the timing of marriages. Malhotra (1997) concluded that there are certain bases of gender equality within the traditional system of Javanese marriages. His finding indicated the emergence of gender differences in the urban middle class that are entirely absent in rural Java. Family class and status seem to hold very strong relevance in the urban context for the marriages of daughters, but not at all for sons (Malhotra 1997). Women in the urban setting are much less likely to engage in work before marriage than their rural counterparts, but even for those who do, employment does not seem to be serving as a means of independence or alternative to marriage. Urban Javanese women are more likely than their rural counterparts to attend school and have had a say in their choice of a spouse; they also were less likely to be economically independent (Hollander 1997; Malhotra 1997).

Premarital Sexual Intercourse

Sex before marriage is a relatively uncommon practice and against social norms in Indonesian society, though the rising numbers of adolescent premarital pregnancy indicate that the norm is under increasing pressure. Indonesia Young Adult Reproductive Health Survey (IYARHS) 2007 shows that very few unmarried adolescents admitted having unwanted pregnancies, because pregnancy among unmarried women is socially unacceptable and not sanctioned by religion, therefore such data is not available for Indonesia (CBS and Macro-International 2008b).

Although on a social normative level, premarital sexual intercourse is considered improper behavior for both men and women, in reality social discrimination and stigmatization are more strongly reserved for women, reflecting the ‘double standard’ found in most Asian countries (Cleland and Ferry 1995). This ‘double standard,’ however, is much less pronounced in Indonesia than for instance in Thailand (Ford and Kittisuksathit 1994). In Indonesia, premarital sex is also disapproved of for males. IYARHS 2007 showed consistently that the percentage of young men and women aged 15–24 who admitted having sexual intercourse was only 2.7 % of females and 14.2 % of males. Since premarital sex is considered culturally unacceptable for both genders so a strong association between young people’s attitude toward premarital sex and their sexual behavior may be expected. The IYARHS 2007 data shows that 22 % of young females and 44 % males aged 15–24 considered premarital sex personally acceptable, perhaps indicating not only the potential for, but also actually higher than the fore-noted admitted, levels of sexual intercourse experience (CBS and Macro-International 2008b).

Sex outside marriage at an early age is very likely to occur in the absence of adequate knowledge of reproductive health and safe sex increasing the risk of unwanted pregnancy, the complications of abortion (illegal in Indonesia), STIs, and HIV/AIDS. Some studies found that SRH education can delay sexual debut, and thus decreasing premarital pregnancy and other problems including sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV/AIDS (Ford et al. 1992).

Since many ministries have carried out their own SRH-related programs with different focuses and targets, more integrated sexual reproductive health policy needs to be developed as a national plan that can provide direction to SRH education programs that are suitable for the needs of young people (Achmad and Xenos 2001).

Contraceptive Use

The current level of contraceptive use is important for measuring the success of National Family Planning Programs (NFPP) in Indonesia. The objective of NFPP is to institutionalize the norm of the ‘small, happy, and prosperous family’ with new vision ‘all family participate in FP’ with a mission to create small, happy, and wealthy families. The concept of the small family promotes regulation of birth intervals and number of children in the family through the use of contraception methods (CBS and Macro-International 2008a).

IDHS 2007 data show that more than 60 % of married women are using contraception, with 57 % of them using modern methods such as injectables, pills, and implants. Traditional methods are no longer popular among married Indonesian women. Among modern methods, injectables are the most commonly used for both currently married and ever married women. Urban women are relying more on IUDs, condoms, and female sterilization; while rural women more commonly use injectables and implant methods. Women aged 15–19 and older women aged 45–50 are less likely to be using contraception than the women in mid-childbearing ages (20–39) (CBS and Macro-International 2008a). With respect to the younger age group, this highlights the point that for many an early first pregnancy is considered highly desirable within marriage. Since premarital sexual relationships are culturally unacceptable in Indonesia, so contraception services are unavailable for unmarried young people. We address the obstacles and progress being made to make such services available to unmarried adolescents in the final section of the chapter on programs and policy.

Premarital Pregnancy and Abortion

Premarital pregnancy and abortion remain highly stigmatized and isolating experiences for single women in Indonesia. Government family planning services are not legally permitted to provide contraception to single women or men and their access to reproductive health care is very limited. Women who experience unplanned premarital pregnancy face personal and familial shame, compromised marriage prospects, abandonment by their partners, single motherhood, a stigmatized child, early cessation of education, and an interrupted income or career (Bennet 2001).

Young women were only able to legitimately continue premarital pregnancy through entering a marriage. Given elective abortion in Indonesia is illegal, and a legal abortion is almost impossible to quantify for, many girls and women, out of necessity, resort to abortion to avoid compromising their future because they are not married (Bennet 2001). Most induced abortions were conducted for unmarried young women, because they have limited knowledge and access to contraception in preventing unwanted pregnancy (Hasmi 2001). Although, they strongly feel that abortion is a sin, many of them consider abortion preferable to continuing with the pregnancy if a man refused to take responsibility for the pregnancy or rejected marriage as a solution. They often argued that causing personal and family shame, having a child out of wedlock and raising a fatherless child, were greater sins than abortion (Bennet 2001). There has been a continuing debate about legalizing abortion in Indonesia (Hull et al. 1993); however, the religious and cultural opposition is so strong that it looks unlikely to pass in the medium term.

Having alluded to a range of key parameters pertaining to adolescent pregnancy in Indonesia, we now turn to a richer exploration of the nature of youth sexual culture that shapes such risk.

Sexual Culture of Young People in Indonesia

There is widespread recognition of the social variability in sexual forms, beliefs, ideologies, identities, and behavior, and the existence of different sexual cultures across the Indonesian archipelago. For instance Acehnese and Minangkabau people have Sharia law to regulate their sexuality. The application of Sharia law in Aceh has increased since the award of greater political autonomy to the province. Thus, in Aceh, the Sharia police seek to prohibit youth sexuality by publicly caning or whipping young men and women caught and suspected of engaging in sex with a premarital partner (Afrida 2007). By contrast in more moderate Java, there is a cultural expectation of socio-personal self-regulation; whereas, Balinese people regulate their forms of sexuality in terms of the Hindu religious strictures. Sexuality has a history, or more realistically, many histories, each of which needs to be understood both in its uniqueness and as a part of an intricate behavioral patterns (Longmore 1998).

The current sexual culture in Indonesia with regard to young people may be usefully understood as interplay of traditional and modern (liberal view) pressures and tendencies. As noted above, the trend toward increasing premarital sexual intercourse is also partially related to the increasing duration of full time education and delays in the age of marriage (Ford and Kittisuksathit 1996). Although the majority of young people still express the traditional values of sexual behavior by disapproving of sexual activity before or outside marriage, some of them are only approving if the couples planned to marry. Yet, the number of teen pregnancies and abortions has been increasing throughout the country since young people have limited knowledge and access to contraception services to prevent their premarital pregnancy (Adioetomo and Achmad 2002).

In the past, it has often been assumed that sexual activity has only increased among urban youth. However, a qualitative study conducted in South Kalimantan by anthropologists from the University of Indonesia suggests that there was no significant difference between urban youth and those of rural areas (Murdijana 1998). Moreover, youth perceptions of pregnancy, abortion, and family planning were the same in urban and rural areas (Murdijana 1998).

Courtship in Indonesia does not involve long-term cohabiting sexual relationships (Bennet 2001). Cohabitation before marriage is considered indecent in Indonesia (Bennet 2001). The derogatory term kumpul kebo meaning ‘a group of buffaloes’ is used to describe couples who live together prior to marriage. Cohabitation is interpreted as deviant and dangerous because of its independence between motherhood and marriage (Bennet 2001). This form of sexual transgression from the hegemony of sexual ideology is particularly offensive because it threatens corporate identity, which includes considerable investment in the ideals of female virginity prior to marriage and the containment of female sexuality within marriage (Bennet 2001).

The value of virginity in conservative Indonesia is regarded as crucial for marriage. Virginity is primarily a concern for the girl’s family, which bears the consequences when she bears a child (Utomo 1999). Virginity is valued in those societies in which bastardy has serious deleterious outcomes for families (Abramson and Pinkerton 1995). As expected, virginity is highly regarded among both women and men. Almost all women and men say that it is important for a woman to maintain her virginity (98–99 %). This perception does not vary much by age or residence. However, women and men with less than primary education are slightly less likely than educated respondents to uphold the crucial importance of a woman’s virginity (CBS and Macro-International 2008a).

Sociosexual Lifestyles of Unmarried Young People in Indonesia

A map of Indonesia proportionate to size of population would show Java as the most densely settled island, with over 60 % of the total population, but only 6 % of the land area. The Javanese is the ethnic group that dominates the center of the island (approximately 45 % of total population) (CBS 1995). They comprise the largest single ethnic group not only in Indonesia, but also in Southeast Asia as a whole (Hugo et al. 1987). Although over 90 % of the Javanese are Muslim, today the culture blends in a syncretism, drawing on historic layers of Hinduism and Buddhism, as well as more ancient Animist roots. Islam has generally taken a fairly liberal form, termed Abangan in Java, although there is also a more ‘purist’ form known as Agama Islam Santri.

Sexual health vulnerabilities emerge from the complex interaction of sexual culture and sociohealth policy response (Ford and Kittisuksathit 1994) within the specific context of place. Javanese culture and the social changes occurring within Central Java, shape both the expressions of sexual lifestyles and the contested debates concerning appropriate protective sociohealth response (Shaluhiyah et al. 2007).

Exploring the sexual lifestyles of youth (aged 18–24 years of age) in Central Java, with particular reference to SRH vulnerabilities and the implications for policies and programs in the Urban Health System means seeking to understand the nature of sexual behaviors in terms of broader meanings associated with more general social and leisure tendencies. The patterns of findings identified are thence discussed and interpreted with reference to wider social and lifestyle theory.

Prior to presenting the key findings on the parameters of the youth sexual culture and their associations with broader sociosexual lifestyles in Central Java, some contextual reference is made to prior research into sexuality in Indonesia and some core notions of Javanese culture.

Mysticism has been described as the essence of Javanese culture (Mulder 1998). It permeates Javanese life and its vocabulary. Some Javanese words are sometimes hard to understand in all their shades of meaning. Eling is another one of these frequently used terms that are difficult to translate precisely (Mulder 1998). The word can only be understood by looking at its context. Javanese will understand it intuitively. Basically, eling means’ remember,’ eling also means being conscious of the consequences of our actions and our individual responsibility. Therefore, eling in its basic meaning is of great importance to the concept of self-awareness and is considered of great importance in Javanese philosophy (Mulder 1998).

In terms of Javanese cultural values, to be Javanese means to be a person who is civilized and who knows his manners and his place (Koentjaraningrat 1989). The individual serves as a harmonious part of the family or group. Life in society should be characterized by harmonious unity, ‘rukun’ (Mulder 1998). The language, which is used mainly with the family, is an important part of the process called Javanization (being Javanese). The Javanese language has three levels, each with its own vocabulary, prefixes, suffixes, and etiquette. Ngoko or low-Javanese language is the language used at home. Krama is a much more elegant and refined language and is used to talk to people of high-social status. Madya or middle-Javanese is a less refined language than krama. It is used by farmers, the working-class and in situations where krama sounds too formal.

The Javanese concept of life describes life as a series of hardships and misfortunes. They always teach their children to be in a continuous state of eling and prihatin, or‘ forever feeling concern’ (Koentjaraningrat 1989). They should develop an attitude of accepting the hardships and misfortunes of fate willingly. The elements of Javanese culture in which the symbolic system finds the most expressive manifestation in the everyday life of Javanese society are language, art, religious beliefs, rituals, magic, and numerology (Koentjaraningrat 1989). In terms of the aspects of sexual relationship, the language, religious beliefs, and concepts of life and values are probably the dominant symbols and factors, which may affect youth Javanese sexual culture. In terms of youth sexuality, the key point is that the special emphasis on mindfulness in Javanese culture is expected to be applied as self-control regarding sexual impulses and interactions. Transgression of such capabilities will result in a loss of respect within developing sexual relationships. The display of vulgar behavior lacking Javanese sensibilities has a social impact in Central Java, which corresponds to what Bourdieu (1991) has described within Western culture as a loss of cultural capital, with negative implications for social worth and potential relationship development.

The Basic Parameters of Sexual Health Risk

The basic pattern of level of sexual experience in Indonesia is relatively low in comparison with some other cultures such as Thailand or Brazil (Ford et al. 1992; Ford and Kittisuksathit 1996; Ford et al. 2003) with, for instance, only around 22 % male and 8 % female university students engaging in premarital intercourse (Ford et al. 2007). A large-scale comparative survey (2,000 person sample survey) of the sexual lifestyles of factory (low income) and university (middle class) youth revealed very little difference between the findings for the two groups, which in turn highlights the primacy of the impact of the shared Javanese culture. The pattern was basically one of relatively low levels of premarital intercourse, but (of concern) very low levels of contraceptive precautions within such activity (Ford et al. 2007).

This study sought to explore Javanese youth sexuality within the wider context of values and leisure lifestyles. Cluster analysis (Bijnen 1973; Lawson and Todd 2002) was undertaken separately for males and females, upon a wide range of variables including attitudes to premarital intercourse, contraception, condom use, sexual techniques, pornography, homosexuality, and gender. The ensuing analysis at the level of four basic clusters showed strong associations of sexual lifestyles to leisure lifestyles, traditional modern tastes and religiosity. Across the overall clustering, the scale, which most strongly discriminated between the different clusters, was a series of items pertaining to social activity, including going to parties, nightclubs, dating, staying away overnight, and alcohol consumption. This dimension relates in Indonesian culture to the concept of gaul, which corresponds to a sense of young people who pursue a more open, socially active lifestyle, as against the opposite who lead more closed, restricted, introverted lifestyles, who are termed kurang gaul (Ford et al. 2007). The more gaul clusters expressed the more liberal sexual attitudes and behaviors; although, it is important to note that these are not the liberal recreational sexual lifestyles found among youth in many other parts of the world (Ford 1992). The general point here is that youth sexual lifestyles in Java are closely related to wider social activity, dress and leisure behaviors, which cohere with religiosity, traditional and modern values, and sense of self-identity. In terms of tastes and identity within the pluralist culture of Indonesia, gaul youth associate themselves with a range of globalizing cultural trends and influences, while kurang gaul are more likely to express a sense of solidarity with the wider Muslim world (Ford et al. 2007).

In order to convey some greater sense of the feelings involved in, and the gendered and interactional nature of, youth sexual culture, we present some qualitative findings from a recent study of Javanese university students (Shaluhiyah 2006). To understand why (in this case) university students choose and value certain manners and acts within their sexual relationships, and the importance they attach to their choices, we have to explore in more depth the nature of their sexual interpersonal relationships. In turn, their sexual behaviors are more generally located in networks of relationships and perceptions of relevant cultural discourses (Chaney 1996) as briefly noted above.

The Nature of Javanese Youth Interpersonal Sexual Relationship

In order to understand the nature of sexual interactions of Javanese students, case studies using in-depth interviews were an appropriate mode of data collection for sensitive topic areas such as the respondent’s actual sexual experiences. This section discusses the way the sexual aspect of romantic relationships begins. It includes the importance of the first sexual experience to the young couple, the possible sexual pathways on which couples travel, and the partners’ decisions to become sexually involved. Other areas of inquiry were related to strategies to initiate and negotiate sex, the possibilities to communicate and discuss safe sex within relationships, the attitudes about consequences of sexual activity, and the attitudes toward condom and other contraceptives use.

In earlier Javanese tradition, first intercourse was most likely to occur in adolescence within marriage. These days, adolescence is now an extended period before marrying, and there may be contact with the stimulus of sexually explicit material through videos, magazines, and the Internet, especially since censorship has been relaxed. So, perhaps there are increasing levels of sexual experimentation, including sexual intercourse, among young people as a consequence of these factors.

According to American sociologists, a couple’s first sexual intercourse experience and later sexual interactions often follow a sexual script that dictates social and sexual conduct (Sprecher and McKinney 1993). These are influenced by aspects of the sexual scripts that the couple has learned both from society and their own interactions (Sprecher and McKinney 1993).

As noted above, Javanese young people’s first premarital sexual intercourse most often occurred within a serious and long-term dating relationship. It is a usually a spontaneous or unplanned event, occurring at a men’s boarding house or at the home of the young women, which did not include contraceptive practices. Nonetheless, there was a young man who commented that sexual interactions among young students were not always spontaneous. They were sometimes planned, for example, staying overnight together in a hotel.

Finally after my boyfriend has expressed his wishes to propose marriage to me next year and he also has given me an engagement ring personally, then I could not reject making love to him. The day after he gave me the ring, we celebrated our personal engagement by sleeping together in a hotel and we had sexual intercourse. At that time I was quite sure that he was my husband to be. Therefore, I had the courage to make love to him. (Heni, female, age 20)

Gender differences have also been found in some aspects of the sexual script during first intercourse, especially in emotional reactions after the first intercourse. These gender differences were not very large. Case studies have shown that the emotional reactions of young women were more likely to be guilty ones. Young women experienced more negative or less pleasant reactions to first intercourse than did young men. They described their first sexual intercourse as extremely painful and disappointing. A participant of the case study described her feelings after first intercourse.

After having made love for the first time I felt sorry and cried. It seemed that I had lost everything. Apparently the uneasy feeling still exists. I was afraid that his respect for me had deteriorated because my relationship with him had been restricted, so that I had to obey him. I was frightened that he would act arbitrarily to me. I also worried about being pregnant, although we used a condom. I didn’t really enjoy making love for the first time due to a number of different reasons, such as feeling fear, anxiety, terror, all mixed up together. That made me disappointed and I suffered from pain instead of the feeling of sensuous enjoyment. (Heni, female, age 20)

Although both men and women described feelings of fear and anxiety surrounding their first intercourse, it was often not a pleasurable experience for females. Young men’s emotional reactions after first intercourse included feeling more responsible in terms of continuing their relationships. If their girlfriend became pregnant, the young men would be under substantial pressure from his girlfriend’s parents to marry their daughter immediately.

In many cases, a dating relationship does not always involve a sexual relationship when the partners have different expectations of and goals for the relationship. Traditionally, young men prefer to engage in sex earlier than young women do in relationships. Young women tend to wait until they feel ready to engage in premarital sex (Sprecher and McKinney 1993). As discussed earlier, in Javanese cases, young men also asked to have sex earlier than young women, but they never forced it if their girlfriends did not feel ready (such use of pressure would show a face-losing loss of self-control in terms of Javanese values). Women preferred to include sex in their love relationship if they believed that their relationships would continue and marriage was guaranteed. The reasons most frequently mentioned by young women for resisting sex were practical ones, such as a fear of being pregnant, and not wanting to have a promiscuous relationship. When the relationship had developed over a period of time and held the prospect of a formal committed relationship (marriage), young women believed, to a greater degree than men, that being sexually rejected would be uncomfortable and unexpected. Thus, they tended not to refuse their partners’ demands.

The majority of sexually experienced young students were still actively dating their sexual partners. The data also showed that the frequency of sexual intercourse among dating couples was mostly low (less than twice a month). The case study findings were also consistent with the survey. There was a wide range in the frequency of sexual intercourse among sexually experienced dating couples. While some dating couples had regular sexual interactions with their steady partners (most often twice a month), the majority of them had sexual intercourse only incidentally or not at any definite time. A minority did not continue to have sexual intercourse. Some couples commented that the main constraints or inhibiting factors were fewer opportunities and less privacy to do so. Some couples also mentioned that they actually wanted to stop their sexual behavior because of the intensity of sinful feelings at behaving in a socially unacceptable way. Apparently, both genders were scared about personal performance, acceptability, and the possible negative outcomes of having intercourse.

Women wanted to continue having sexual intercourse in order to maintain their steady relationship, perhaps because they felt they had already lost the most valuable thing in that relationship—their virginity. Therefore, they felt that they needed to be tied to the higher quality of the relationship. Somewhat surprisingly, the case studies indicated that women felt that men were somewhat more reluctant in later intercourse than first intercourse. It was apparently the young men who felt more anxiety and responsibility about the possible outcomes of intercourse.

For the young women, premarital pregnancy was feared, primarily because it was evidence of ‘sinful behavior’ and a ‘traumatic accident.’ Some young women knew siblings who had had traumatic experiences because of unwanted pregnancies. All parents would be extremely disappointed by a daughter’s premarital pregnancy, because it would entail a loss of a family reputation and enduring shame, but the disappointment did not extend to extreme punishments. Most young women’s parents would try to convince the young man and his family, hoping that he would be responsible and marry and care for their daughters and the child. The main options for young women facing premarital pregnancy would be firstly to consider marriage and secondly to seek a termination. If the couple did not feel emotionally and financially ready to take the responsibility of having a child, both sets of parents (man’s and woman’s) would look after their child. It is interesting to note that premarital pregnancy was blamed on both the young man and woman. As a result, not only the couple but also the families would bear the consequences of the premarital sexual activity of their children.

Probably, the most disturbing issue to emerge from the discussions concerned the use of ineffective forms of contraception during sexual intercourse with love partners. Most young men in the group discussions commented that ‘coitus interuptus’ or withdrawal was the most popular method to prevent pregnancy. The discussion revealed a widely varying level of knowledge and awareness of SRH, including contraceptive issues, among young students. Only a minority was well informed. Many were confused about particular issues such as reproductive health matters, and some had very little idea about sexual diseases.

A young woman described her knowledge of how to prevent pregnancy:

My friend told me to prevent pregnancy the girl should squat and jump after intercourse in order to remove the sperm from the vagina. (Nana, female, age 22)

Young man gives a similar opinion:

In order to prevent pregnancy, usually the couple tried to combine many contraceptive methods. Besides using BL technique or withdrawal, they also use the calendar system and drink pineapple after intercourse to kill the sperm (Prayit, male, age 22).

Many premarital sexually active young students rely on the highly ineffective method of ‘coitus interuptus.’ The main reason for nonuse of condoms was that, although condoms were widely available and accessible, young students believed that the service was primarily for married people. For the unmarried, buying a condom was very embarrassing. Strong cultural barriers exist which make it difficult for young students to acknowledge being sexually active and hamper the provision of such services for the unmarried.

Very few young students seemed to have much understanding about SRH, such as how contraceptive methods worked and how conception happened at the moment of sexual unions. Consequently, interpretations of the perceived level of risk in terms of an unwanted pregnancy or sexual disease are often difficult when the knowledge about those contraceptive methods and reproductive health matters are incomplete.

One female student in the case study describes this very effectively.

We never got the information about health, especially on SRH. We just get it from television. Moreover, I am not interested in attending seminars on sexual health; I thought that it was not my subject of study. (Ika, female, age 20)

According to these students, the low level of knowledge in terms of SRH is caused by a lack of adequate information provided to the young students by the government health services. At present, there is no practical effective sex education in schools. Indeed, the main source of sex information is discussions about the knowledge of sexuality among friends and in the mass media, primarily through the Internet, and pornographic materials. These are, of course, not ideal for shaping the behavior of young unmarried people. Thus, it is important to fully and explicitly inform young people of the risks and options they face within a carefully structured, school sex education setting, which also provides the opportunity to discuss values. Such a perspective is supported by a number of international studies, which indicate that explicit sex education does not encourage sexual experimentation or irresponsibility (Ford et al. 1992). Furthermore, a the strong demand for adequate information was expressed and indicated in enthusiastic discussions on sexual health matters, such as contraceptive devices, pregnancy, and STDs, during the Central Java study focus group discussions.

Programs and Policies Addressed to Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health in Indonesia

In line with Indonesia’s commitment and response to the ICPD, the National Committee on Reproductive Health was formed in 1998. The National Committee on Reproductive Health is divided into four task forces: on safe motherhood, family planning, ARH, and elderly reproductive health. The role of the National Committee is to provide directional policies and intervention strategies, to monitor the task force activities, and to facilitate collaboration with other sectors or institutions. Since decentralization was enacted, by giving full autonomy to district level; subsequently local government has responsibility of implementing and addressing reproductive health issues. In fact, many local governments have limited capacity and resources to maintain and implement these programs.

Although the government of Indonesia has committed itself to implementing the SRH programs as mandated by ICPD in 1994; the implementation of the ARH program nationally has not been considered. Various ARH activities have been conducted sporadically in a few provinces, sponsored by foreign agencies, GO, and local NGOs. Some of the private schools (which are perhaps more progressive than the public ones) have tried to introduce sex education through a school-based curriculum and peer-based programs, which are undertaken by some NGOs have been launched to reach adolescents to provide basic information on sexuality and reproductive health. These indicate that young Indonesians are amply capable of addressing sex education matters in a mature and open manner (Ford and Siregar 1998). The problem is that most policy makers are in the forefront of opposition to the provision of sex education in schools or to allowing young people to have accessibility to reproductive health services (Utomo 2002).

There are two current models of SRH implementation programs covering youth’s SRH needs. The first are the clinical-based and outreach programs; the second are the community and group empowerment programs to reach adolescents in rural areas, and the referral system programs for handling youth problems (Hasmi 2001). The clinical-based model is mainly developed and undertaken by local NGOs, particularly by the Indonesian Planned Parenthood Association (IPPA/PKBI), which has recently renamed their clinics ‘youth centers.’ The youth centers, which are already developed in many provinces, are organized and managed by trained young people who provide services including counseling, hotline services, basic medical services, group discussions, and other supportive activities. The IEC activities in school and community settings have also been the main concern of youth centers in providing appropriate and relevant information on SRH. Some centers have attained a considerable improvement in terms of sustainable services and programs. However, because the centers offer programs that are considered merely as part of the social services, the continuity of the services is greatly dependent on financial support from various organizations, including local and international agencies (Hasmi 2001). The other weakness of the youth centers is that their coverage has generally been limited by resource constraints, including the limited number of qualified persons to run the centers. It is, therefore, important to note that to reach such large populations in resource-limited settings means that cost-effectiveness and sustainability are of paramount importance (Hasmi 2001). The second model is run and initiated by the government and emphasizes empowering the community in rural areas. The Family Planning Coordinating Board (BKKBN) has launched a parent–education program in two Java provinces and has produced separate parent–education curricula for younger and older adolescents covering reproductive physiology, family relationships, contraception, and other topics. This program has been carried out through parents’ groups, which hold a series of meetings to discuss the content of the curricula, and to review parents’ experience in discussing these issues with their children. Other adults, including religious and youth-group leaders, are also using the curricula to discuss these issues with young people (Hughes andMcCauley 1998).

The BKKBN has also been empowering their cadres at village level to become involved in providing information to adolescents on SRH. Although initially the main tasks of the cadres are to provide services concerning family planning matters for married women, such as providing contraception and counseling programs; they are now expected to disseminate information on SRH for adolescents, through empowering their parents. PIK-KRRs (Centers of information and counseling on adolescent reproductive health) located in subdistricts have also been developed by BKKBN since 2001. The PIK-KRR programs are to provide adolescent with information and counseling on reproductive health in particular with sexuality, HIV/AIDS, and drug abuse. The activities are organized and managed by and for adolescents at district level with the support and guidance between BKKBN and other-related sectors. Currently, there are estimated to be approximately 5,284 PIK-KRR programs across the country, which means every subdistrict has at least one PIK-KRR. Again, since decentralization was enacted, these programs are mostly depending on the priority of districts’ concern with SRH of young people.

The other model that has been initiated by Ministry of Health under health center program is called PKRR (center of adolescent reproductive health). This program has been run by health center staff and provides counseling, information, and services particularly related to sexuality and reproductive health of unmarried youth including pregnancy problem and contraception. Unfortunately, not all health centers have such a program because of limited trained staff resources and other cultural barriers. Some survey findings suggest that many ARH program run by health centers were underutilized by young people because of lack of information, inconvenience, and unfriendly services to the young people.

The State of Ministry of Women Empowerment has conducted a small-scale project on reproductive health for female adolescents in two provinces, Jakarta and West Java. This project was remarkably successful and involved many key people such as students, parents, teachers, local authorities, and religious leaders participating and discussing these issues. Furthermore, there was much enthusiasm from the participants mainly young women who wanted to learn about SRH-related topics. Unfortunately, this project is being phased out and is only on a ‘trial’ stage, so the need for strong financial and political support from the government to continue such programs is of paramount importance.

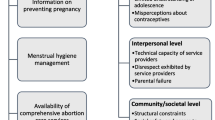

The Ministry of National Education has also been quite successful in providing IEC on SRH for young people though it is out of school programs. Unfortunately, the implementation of these programs in schools has become a ‘hidden agenda’(Utomo 2002) (Fig. 2).

The government of Indonesia has faced great difficulty in developing policies to deal with the reality of the SRH problems, particularly for young people. Conservative/moralistic perspectives sometimes confuse the reality of the situation, especially with regard to adolescent reproductive health problems (Jones 2001). They are unwilling to accept the actual situation being faced by many adolescents—that adolescents and young people are sexually active and that therefore problems of unwanted pregnancy, abortion, STDs, and HIV/AIDS need real solutions (Jones 2001).

There have been many policy documents issued by the government that focus on HIV/AIDS prevention programs. For instance, the National Strategy on Management of HIV/AIDS in Indonesia was published in 1993; the instructions of the Minister of Education and Culture of Indonesia on HIV/AIDS prevention through education were issued in 1997; the Ministry of Education and Culture in Indonesia issued guidance on HIV/AIDS prevention through education in 1997 (Utomo 2003). These policies were developed and initiated by the Ministry of National Education, because of the worrying increase in the risk of HIV/AIDS among young people. Although there is not any specific mention of SRH in school settings, these policies mention that youth is a priority target group. The subject of sexuality is also included in the IEC materials. Unfortunately, the implementation of these policies into the national agenda is faced by many cultural and political constraints. Therefore, it is still in question whether these programs will be implemented nationally in the future (Utomo 2003). However, sporadic ARH programs have been undertaken through small-scale projects by the NGOs and have been supported by the government.

There was a significant shift for ARH in Indonesia in the year 2000. The Minister of Women Empowerment and the head of BKKBN advocated a remarkable policy that pregnant students should be provided with an opportunity to finish their schooling; they should not be expelled from school, but should be given leave from school during pregnancy (Utomo 2003). This policy was expected to give an opportunity for pregnant students to continue their education and career development and to reduce the incidence of premarital abortion (Utomo 2003). Again, some religious, community, and political leaders disapproved of these statements. They assumed that such policies would give the opportunity or encourage young students to become freer in sexual activity.

Since 2004 Ministry of National Education published ‘HIV/AIDS prevention strategy through Education program’ that integrated into school curricula of junior and senior secondary schools, and trained teachers were mandated to carry out this activity. Although this policy was national in scope, by decentralizing the HIV education to province and district level responsibility, the result varied widely depending on the commitment of local authorities and their view of the perceived threat.

Ministry of National Education decree No. 39, 2008 on Guidance and Supervision of student activities was enacted, which includes HIV and drug abuse prevention are mandatory activities within existing curricula and cocurricular activities such as school health efforts, pupil intra-organizations, and student scouts. By collaborating with UN agencies (UNICEF, UNESCO, and UNFPA) and NGOs, Ministry of National Education has published training manuals on SRH, HIV, and drug abuse prevention for teachers in junior and senior secondary schools. Due to limited resources, however, the distribution and utilization of this important material is very limited (UNESCO 2010).

Since intersectoral collaboration among ministries is rarely realized and Ministry of Health, Ministry of National Education, BKKBN, Ministry of Women Empowerment, and Ministry of religion run their own programs, inevitably ineffective programs are often the result. Actually, HIV, sexuality, and reproductive health are subject of interest to young people, unfortunately only limited numbers of teachers have received comprehensive in-service training in these subjects. Many young people were not satisfied with what they learned from textbooks, so they look for SRH information in popular media or Internet without supervision.

To conclude this review of the development of SRH services for adolescents in Indonesia, it is clear that from the efforts of the past three decades there is considerable public and social health expertise in, and understanding of, the type of programs that are urgently needed. Several examples of high-quality programs that have been developed, tested, and implemented have been outlined above. Nonetheless, and especially in light of the demographic and geographic enormity of the archipelago, such programs have as yet had only limited contact with the vast adolescent population. While the Republic of Indonesia does face budgetary constraints, it has shown repeatedly that it does have the capability to implement such health-enhancing programs. The key point is that political opposition from conservative Islam, and the very fear of such opposition, has for decades paralyzed the mass implementation of appropriate SRH services for unmarried adolescents.

Future policies and programs development should be addressed, and consider ways of maintaining young people’s positive norms and values in line with existing culture and religion in each province by enhancing self-efficacy and life skills through school-based sexual reproductive health education and services (Suryoputro et al. 2007). Advocacy should also be conducted continuously to address environmental constraints that impede the adoption of positive sexual health (Suryoputro et al. 2006).

Conclusion

In conclusion, in Indonesia, adolescent pregnancy within marriage is extremely common and socially acceptable. Furthermore, while the total fertility has dramatically declined in Indonesia in recent decades, there are still continuing substantial problems of maternal mortality and morbidity related to early age of pregnancy, partly because the timing of first childbirth has only been slightly delayed. In contrast, adolescent pregnancy outside marriage, and if not leading to marriage, is widely considered culturally unacceptable and has grave personal and social consequences especially for the young woman.

During this same period of recent demographic change, however, there have been major social changes taking place across the archipelago, which have important impacts upon young people’s sexual lifestyles. It is axiomatic that concerns with adolescent pregnancy need to be considered in terms of the particularities of culture and place. Thus, we have attempted to provide some insights into the nature of Indonesian youth culture, with specific reference to pertinent elements of Javanese culture. While not all ethnic groups across the archipelago hold Javanese values, there is widespread-shared antipathy toward casual and premarital intercourse. Nevertheless, reference has also been made to a process of widening pluralization of youth sexual lives reflecting broader social changes in values and leisure lifestyles. Thus, among the more liberally inclined strand (gaul) of Indonesian youth, there are increasing levels of premarital (but generally not casual) sexual intercourse. This transition clearly warrants the provision of appropriate SRH services. This demand has also been given some urgency for many Indonesian health practitioners by the advent of the parallel threat of HIV transmission. Similarly, just as effective premarital pregnancy preventing educational and health service programs have been rejected on conservative ‘moralistic’ grounds, so potentially HIV preventing public promotion of condom use has repeatedly been held back by such religio-political forces.

We have stressed that sexuality is a highly contested arena of contemporary Indonesian cultural politics, and this contestation is no more hotly debated, than with respect to youth sexuality. The very process of recent democratization and decentralization has facilitated wider and more open debate on sexual matters, and greater polarization has emerged (or at least become more explicitly articulated) between liberal and conservative positions. Furthermore, this decentralization of power and social and health service decision-making holds out the potential for more diverse social and public health strategies in different localities. For instance, we briefly noted the more draconian methods of regulation of youth behavior based upon Sharia law employed in Aceh, in contrast to the more tolerant strategies in Central Java. Thus, Indonesia in many ways exemplifies family planning programs that have successfully facilitated the overall fertility decline and has never been able to come to terms with or address the growing needs of the premarital, sexually active adolescents. What is so striking about Indonesia as a case study of adolescent SRH is that while the specific contraceptive needs of adolescents have been recognized in Indonesian medical discourse for decades, and numerous materials have been developed and small-scale initiatives tested, very little seems to have been achieved in making such potentially beneficial services universally available in a way that can assist the mass of Indonesian youth.

References

Abramson, P. R., & Pinkerton, S. D. (1995). Sexual nature sexual culture. Chicago: The Chicago University Press.

Achmad, S. I., & Xenos, P. (2001). Notes on youth and education in Indonesia. East-West Center Population Series (pp. 108–118).

Achmad, S. I., Asmanedi, Kantner, A., & Xenos, P. (1999). Baseline survey of young adult reproductive welfare in Indonesia. Jakarta: University of Indonesia.

Adioetomo, S. M., & Achmad, S. I. (2002). Need assessment for adolescent reproductive health programmes. Jakarta: Demographic Institute Faculty of Economics University of Indonesia.

Afrida, N. (2007, 27 January). Aceh women want caning review. The Jakarta Post.

Arkoun, M. (2003). Rethinking Islam today. Annals AAPSS, 588, 18–39.

Bennet, L. R. (2001). Single women’s experiences of premarital pregnancy and induced abortion in Lombok. Eastern Indonesia. Reproductive Health Matters, 9(17), 37–47.

Bijnen, E. J. (1973). Cluster analysis: Survey and evaluation of techniques. The Netherlands: Tilberg.

Blum, R. W. (1991). Global trends in adolescent health. Journal American Medical Association, 265(20), 2711–2719.

Bongaarts, J., & Porter, G. R. (1983). Fertility, biology and behavior: An analysis of the proximate determinants. NY: Academic Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Cambridge: Polity Press.

CBS. (1992). Indonesian demographic and health survey 1991. Columbia: Macro national Inc.

CBS. (1995). Indonesian demographic and health survey 1994. Columbia: Macro International Inc.

CBS. (1998). Indonesia demographic and health survey 1997. Calverton, Maryland: CBS and MI.

CBS. (2002). Result of the 2000 Indonesian population census. Jakarta: Central Bureau of Statistics.

CBS, & Macro-International. (2003). Indonesian demographic and health survey 2002. Calverton: BPS and ORC Macro International.

CBS, & Macro-International. (2008a). Indonesian demographic and health survey 2007. Calverton: BPS and Macro International.

CBS, & Macro-International. (2008b). Indonesian young adult reproductive health survey 2007. Calverton: BPS and Macro International.

Chaney, D. (1996). Lifestyle. London: Routledge.

Cleland, J., & Ferry, B. (Eds.). (1995). Sexual behaviour and AIDS in the developing world. London: Taylor and Francis.

Cleland, J., & Hobcraft, J. (2011). Reproductive change in developing countries: Insights from the world health survey. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dipa, A. (2011, January 7). Prosecutors demand Ariel be jailed for five years’ The Jakarta Post.

Ford, N. J. (1992). The AIDS awareness and sexual behaviour of young people in the South West of England. Journal of Adolescence, 15, 393–413.

Ford, N. J., & Kittisuksathit, S. (1994). Destinations unknown: The gender construction and changing nature of sexual expressions of Thai youth. AIDS Care, 6(5), 517–531.

Ford, N. J., & Kittisuksathit, S. (1996). Youth sexuality: The sexual awareness, lifestyles and related-health service needs of young, single, factory workers in Thailand. Bangkok: Institute of Population and Social Research Mahidol University.

Ford, N. J., & Siregar, K. N. (1998). Operationalizing the new concept of sexual and reproductive health in Indonesia. Journal of Population Geography, 4(1), 11–30.

Ford, N. J., Fort-d’Auriol, A., Ankomah, A., Davies, E., & Mathie, E. (1992). Review of literature on the health and behavioural outcomes of population and family planning education programmes in school settings in developing countries. Institute of Population Studies, University of Exeter.

Ford, N. J., Siregar, K. N., Ngatimin, R., & Maidin, A. (1997). The hidden dimension: Sexuality and responding to the threat of HIV/AIDS in South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Health and Place, 3(4), 249–358.

Ford, N. J., Viera, E. M., & Villela, W. V. (2003). Beyond stereotypes of Brazilian male sexuality, qualitative and quantitative findings from Sao-Paulo, Brazil. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 5(1), 53–69.

Ford, N. J., Shaluhiyah, Z., & Suryoputro, A. (2007). A rather benign sexual culture: Socio-sexual lifestyles of youth in urban Central Java. Population, Space and Place, 13(1), 59–78.

Fryer, D. W. (1970). Emerging Southeast Asia: A study in growth and stagnation. London: George Philip and Son.

Hasmi, E. (2001). Meeting reproductive health needs of adolescent in Indonesia. Jakarta: UNESCO Indonesia.

Hefner, R. (2002). Civil Islam: Democratisation and violence in Indonesia: A comment. In Review of Indonesian and Malaysian Affairs, 36(1), 67–75.

Hollander, D. (1997). Urban Javanese women postpone marriage but are less financially independent than their rural counterparts. International Family Planning Perspectives, 23(4), 186–187.

Hughes, J., & McCauley, A. P. (1998). Improving the ft: Adolescents’ needs and future programs for sexual and reproductive health in developing countries. Studies in Family Planning, 29(2), 233–245.

Hugo, G. J., Jones, G. W., Hull, T. H., & Hull, V. J. (1987). The demographic dimension in Indonesian development. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Hull, T. H., Hull, V. J., & Singarimbun, M. (1977). Indonesia’s family planning story: Success and challenge. Population Bulletin, 32(6), 1.

Hull, T. H., Sarwono, S. W., & Widyantoro, N. (1993). Induced abortion in Indonesia. Study of Family Planning, 24(4), 241–251.

Jones, G. W. (2001). Which Indonesian women marry youngest, and why? Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 32(1), 67–77.

Koentjaraningrat, R. M. (1989). Javanese culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lawson, R., & Todd, S. (2002). Consumer lifestyles: A social stratification perspective. Marketing Theory, 2, 295–307.

Longmore, M. A. (1998). Symbolic interactionism and the study of sexuality. The Journal of Sex Research, 35(1), 44–57.

Malhotra, A. (1997). Gender and the timing of marriage: Rural-urban differences in Java. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 59(2), 434–450.

Masqood, R. (1994). Islam. London: Hodder Headline Plc.

Ministry-of-Health. (2009). National basic health survey (Riskesdas). Jakarta: National Institute for Health Research and Development.

Mulder, N. (1998). Mysticism in Java: Ideology of Indonesia. Amsterdam: The Peppin Press.

Murdijana, D. (1998). Needs and risks facing the Indonesian youth population. Cerita Remaja Indonesia.

Shaluhiyah, Z. (2006). Sexual lifestyles and interactions of young people in Central Java and its implication to sexual and reproductive health. Exeter: University of Exeter.

Shaluhiyah, Z., Ford, N. J., & Suryoputro, A. (2007). Socio-cultural and socio-sexual factors influence the premarital sexual behavior of Javanese youth in The Era of HIV/AIDS. Indonesian Health Promotion Journal, 2(2), 61–72.

Siregar, K. N. (1999). Maternal mortality and morbidity in Indonesia. Exeter: University of Exeter.

Sprecher, S., & McKinney, K. (1993). Sexuality. London: Sage Publications.

Suryoputro, A., Ford, N. J., & Shaluhiyah, Z. (2006). Determinants of youth sexual behaviour and its implications to reproductive and sexual health policies and services in Central Java. The Indonesian Journal of Health Promotion, 1(2), 60–71.

Suryoputro, A., Ford, N. J., & Shaluhiyah, Z. (2007). Influences on youth sexual behaviour in urban Central Java: Implications of sexual reproductive health policies and services. Makara Health Series Journal, 10(1), 29–40. (in Indonesian).

UNESCO. (2010). Education sector response to HIV, Drugs, and sexuality in Indonesia: An assessment on the integration of HIV and AIDS, reproductive health and drug abuse issues in junior and senior secondary schools in Riau islands, DKI Jakarta, West Kalimantan, Bali, Maluku and Papua. Jakarta: UNESCO.

Utomo, I. D. (1999). Sexuality and relationship between the sexes in Indonesia: A historical perspective. Paper presented at the European Population Conference.

Utomo, I. D. (2002). The politics of reproductive health education and services for young people in Southeast Asia: The myth and forgotten needs. Paper presented at the IUSSP Regional Population Conference.

Utomo, I. D. (2003). Adolescent and youth reproductive health in Indonesia: Status, issues, policies and programs. Jakarta: Policy project, STARH program.

Vatikiotis, M. R. J. (1994). Indonesian politics under Soeharto: A nation in waiting. London: Routledge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Shaluhiyah, Z., Ford, N.J. (2014). Sociocultural Context of Adolescent Pregnancy, Sexual Relationships in Indonesia, and Their Implications for Public Health Policies. In: Cherry, A., Dillon, M. (eds) International Handbook of Adolescent Pregnancy. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-8026-7_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-8026-7_19

Published: