Abstract

This chapter addresses the behavior, thoughts, experiences, and feelings of individuals who have been exposed to strain and stress. First, we introduce the many different approaches associated with both psychological and broader social science-based understandings of coping. We then analyze the extent to which these approaches can be applied in a disaster-related context. In the first part of this chapter, we examine the person-centered coping models that dominate stress research in mainstream psychological approaches. These models are similar to the goal-based models of human nature in which the basic motivation of human beings is to move toward goals while avoiding threats. Depending on the model in question, the main focus lies either in the cognitive processes of appraisal and emotion regulation, attribution of meaning, and religious forms of coping or on the conceptualization as a mental health problem. In contrast, resource-oriented coping theories emphasize the social and material contexts of stress processes. Social contexts and interactions are also more central to the field of community psychology and in the research on social support. Sociology and related social sciences have even broader models in which community coping and resilience of communities are studied as a social or collective process. When considering community resilience, or the application of social capital or local knowledge, the coping resources of larger social units are of primary importance, as collective meanings, emotions, and agency come to the fore.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Transactional coping model

- Religious coping

- Proactive coping

- Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Posttraumatic growth (PTG)

- Conservation of Resources (COR) theory

- Social support

- Social conflict

- Social capital

- Communal coping

- Solidarity

1 Introductory Review of Dominant Approaches

This chapter addresses the behavior, thoughts, experiences, and feelings of individuals who have been exposed to strain or stress. While Chap. 1 covered approaches to understanding and handling "natural" disasters, this chapter addresses the psychological and broader social science-based approaches to handling stress and strain. We then analyze these approaches to determine the extent to which they can be applied in a disaster-related context.

Historically, the subject of coping took root in the mainstream psychologies in the 1960s as a means to mitigate the negative consequences of stress (Folkman 2011) . For a long time, the primary psychosocial consequences of disasters were viewed to be the harm and damage suffered by the individual. Generally speaking, an individual’s stressful life circumstances were considered only in terms of their potential to negatively affect that individual’s ability to function mentally, physically, and socially. It was only later that the positive aspects were recognized as well. Bonanno et al. (2010) and Masten and Narayan (2012) demonstrate the many different ways in which adaptive functioning can occur following a disaster. Under normal circumstances, disasters do not result in psychological and social collapse. In fact, they tend to yield a wide variety of trajectories, most of which are positive in nature. As a result, concepts such as resilience and competence became increasingly important, not only in the macrosocial field of disaster management (see Chap. 1) but also in the area of psychological functioning.

The mainstream psychological coping models can be seen as one specific way of looking at the process of handling strain. These models are similar to the goal-based models of human nature (Carver and Connor-Smith 2010), in which the basic motivation of human beings is to move toward (that is, approach) goals while avoiding threats.

From the very beginning, one of the strengths of the psychological coping models was the fact that they were conceived to yield both positive and negative results. These models address both successful and unsuccessful attempts to manage challenges or threats. Another strength of these models is that they attempt to draw a connection between internal and external elements: with coping models, challenges and threats (internal and external, for example, sickness or an earthquake) and personal resources (internal and external, for example, a high perceived self-efficacy and a resource-rich social environment) are viewed as interrelated factors.

In the first part of this chapter, we examine psychological person-centered coping models (PCCMs; Sect. 2.2). We then explore models that emphasize a broader context (Sects. 2.3 and 2.4) which focus on social and material resources. The former represent the dominant models for stress research in the mainstream psychologies (Folkman 2011) . Depending on the model in question, the main focus lies either in the cognitive processes of appraisal and emotion regulation (Sect. 2.2.1), attribution of meaning (Sect. 2.2.2), religious forms of coping (Sect. 2.2.3), future-oriented forms of coping (Sect. 2.2.4.), or on the conceptualization as a mental health problem (Sect. 2.2.5).

In contrast, the resource-oriented coping theory addressed in Sect. 2.3 places more emphasis on the social and material contextual features of stress processes. In these theories, stress is generally viewed as a loss of resources (Hobfoll 1998) . In the field of community psychology and in research on social support, the social context and social interactions are more central components in considering an individual’s ability to combat strain. Social support is examined both as a part of the PCCM approaches (as an individual mobilizable resource) (Sect. 2.2) as well as in approaches that adopt a more context-specific understanding of coping (Sect. 2.3).

Sociology and related social science specializations also feature models in which coping and the resilience of the community in question are studied as social or collective processes. This approach shows strong similarities with the perceptions of disaster management discussed in Chap. 1. When considering community resilience or the application of social capital , the coping capabilities of large social units (for example, villages and neighborhoods) are of primary importance (Sect. 2.4).

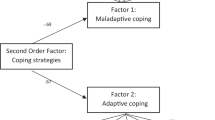

The diagram in Fig. 2.1 provides an overview of the numerous perspectives and dimensions covered by the approaches to coping developed in both psychological and social science contexts. The units of analysis vary in size and their interaction with stressful events can be examined over longer or shorter periods of time, as needed. The diagram displays the past or prior history of stressful and overwhelming experiences. A coping episode can also be selected as a unit of analysis for a particular individual. This episodic approach forms the basis for the most influential psychological model, the appraisal-oriented psychological approach (Lazarus and Folkman 1984) . In newer approaches in developmental psychology, coping is viewed as an adaptive process associated with a potentially long-term series of interactions with a potentially challenging environment. These approaches take into account the fact that a series of stressful episodes can lead to changes both in the individual and in the environment itself (Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2007; Leipold and Greve 2009). In addition, future-oriented coping is beginning to play an important role (Aspinwall and Taylor 1997; Schwarzer and Taubert 2002). Coping models that take the larger context into account include conceptualizations based on dyadic relationships as well as coping at the level of the household (as shown in the access model proposed by Wisner et al. 2004). Models of adaptation for larger social units in hazardous environments were introduced in Chap. 1. We draw upon these models at the end of this chapter.

2 Coping as an Individual Process

One of the most prominent individual approaches to understanding stress is the basic psychological model of coping (Lazarus 1966; Lazarus and Folkman 1984; Sect. 2.2.1) . The development of this model led to a major boom in coping research as well as to extensive additions to the model. These revisions are briefly noted in Fig. 2.1. In certain subfields of psychology (particularly those that concentrated on cognitive processes, health and illness, emotions, development, and personality), the coping approach continued to develop as it was applied to new issues. Following our introduction of the basic model, we address these developments. It was as a result of these changes, for example, that the understanding of “meaning” for the different cognitive appraisals in the context of coping gradually expanded (Schwarzer and Taubert 2002; Folkman and Moskowitz 2004 and Folkman 2011; Sect. 2.2.2) .

In the 1990s, Folkman (2011) observed a reorientation toward resilience and well-being in research on stress. This new focus on resilience corresponded to the emergence of the branch of positive psychology. In addition, interest began to grow about the extent to which the search for sense and meaning (meaning-making) and religious orientations (Sect. 2.2.3) help the coping process. This new approach focused on the positive striving of human beings and the processes of growth and accumulation of resources in the face of challenges.

Another new point of interest was to investigate the ways in which individuals employ proactive coping in striving to achieve universal higher-order goals in life (Schwarzer and Taubert 2002; Sect. 2.2.4). The concept of adaptation used in developmental psychology is universalistic and the understanding of coping embedded in this concept utilizes a broader time scale than single episodes. Moreover, adaptation describes the (mutual) interactions between individuals and their environment, while coping refers exclusively to a single interaction with a specific event. Viewed in this way, coping represents a special type of adaptation that is applied to the broader context of human development by developmental psychologists such as Leipold and Greve (2009).

In the final part of Sect. 2.2, we take a comprehensive look at the pathways of coping associated with health and illness or, more specifically, with psychopathological categories and the need for therapeutic support. The process of coping with extreme suffering takes on a special status. Normally, this process is not addressed within the framework of general psychological coping literature and is instead treated as "trauma" in the branch of clinical psychology (Sect. 2.2.5).

2.1 Appraisal-Oriented Approaches

This aspect of the coping literature was developed in the 1960s in response to findings on the harmful effects of stress on health and well-being. The primary goal was to identify the factors that could potentially reduce these harmful effects. At first, these factors were purely person-centered; they were viewed as psychoanalytically inspired defense mechanisms and as stable properties of the personality like optimism or extraversion (see Carver and Connor-Smith 2010). This remained the dominant view until Lazarus (1966) proposed a model of coping based on the interactions between the individual and the situation, an approach that ultimately developed into the transactional cognitivist appraisal-oriented model of coping (Lazarus and Folkman 1984) .

Person-centered approaches in this tradition claim universal generalizability and explain behavior from the perspective of the individual person. These approaches establish a connection between the external situation and the resources of the person in question. The coping process begins when the internal resources (for example, specific skills or abilities) and external mobilizable resources (for example, social support) no longer correspond to a demanding situation. This is then defined as a stress-inducing situation. One important turning point in what was previously an objective, behaviorist psychology was the assertion that this lack of correspondence was not determined objectively, but subjectively, by means of the cognitive appraisal of the individual exposed to the situation. This appraisal comprises the individual’s subjective evaluation of both the demanding situation as well as the personal (internal) and external (social and material) resources (Schwarzer and Taubert 2002).

Coping is defined as the person’s constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the person’s resources. (Folkman et al. 1986, p. 993)

According to Lazarus and Folkman (1984) , in primary (or demand) appraisal, a person evaluates whether or not there is any challenge, threat, harm, or loss with respect to commitments, values, or goals in his or her interaction with the environment. In secondary (or resource) appraisal, the person evaluates what can be done to overcome or prevent harm or to improve his or her prospects for a beneficial outcome. With regard to personal resources, the individual’s subjectively perceived competence (perceived self-efficacy) is considered to be crucial (Schwarzer and Taubert 2002).

A cognitive appraisal is an individual’s evaluation of the significance of what is happening in the world for his or her personal well-being (Lazarus 1991). Coping comprises two distinct functions: the internal emotion-focused coping, which serves to regulate emotions, and the problem-focused (or instrumental) coping, which serves to change the problematic person–environment situation. Problem-focused coping changes the relationship between the person and his or her environment, while emotion-focused coping induces internal changes in a person’s attention or personal meanings (Folkman and Lazarus 1988). Beginning with the appraisals, emotions accompany the entire coping process. Emotions are analyzed as cognitive systems with an orientation function and tied psychobiologically to an appraisal pattern (for example, sadness to the relational theme of irrevocable loss). Lazarus (1999) emphasizes that emotions are relatively quick reactions in that they flow from the way in which we appraise events as they occur and as more information becomes available:

These appraisals are characterized by negative emotions that are often intense. […] Emotions continue to be integral to the coping process throughout a stressful encounter as an outcome of coping, as a response to new information, and as a result of reappraisals of the status of the encounter. (Folkman and Moskowitz 2004, p. 747)

Subsequently, Lazarus (1991) incorporated coping into a complex cognitive–emotional system. According to Lazarus, the process of evaluating environmental situations triggers certain specific emotions that have evolved to benefit adaptation processes. In a debate with Shweder (1993) regarding the universality of emotions, Lazarus (1993) argued that while certain core themes remain constant in any culture, different cultures define specific criteria for identifying these themes (for example, the necessary criteria for defining a personal insult).

Since the introduction of the coping model, a multitude of types of coping strategies were studied which appeared to be similar in empirical studies despite being derived from very different theoretical frameworks. For example, Folkman and Lazarus (1980) distinguished problem-focused coping (active change of the situation) from emotion-focused coping (control of the negative feelings if the situation cannot be changed), but in practice the coping strategies that people use are often mixtures of these strategies that cannot be separated. Skinner et al. (2003) suggested viewing different forms of coping as action types and proposed that these coping forms are adaptive in relation to the environment, the social resources, and the individual’s own preferences and orientations. Within this typology, they defined five core categories: “problem solving, support seeking, avoidance, distraction, and positive cognitive restructuring” (p. 239).

The deciding factor in the expansion of coping research was the fact that the newly developed measuring techniques opened up the coping construct to quantification and empirical testing. However, the elaborate coping theory proposed by Lazarus (1991) was difficult to operationalize and presented problems with regard to the stability, generality, and dimensionality of coping (Schwarzer and Schwarzer 1996). In addition, a quantitative, measurement-based approach is limited in its ability to investigate special properties, for example, cultural distinctiveness, and places far more emphasis on universally applicable systems of coping. Subjectivity and subjective meanings are reduced to highly simplified elements (see Shweder 1993). Constructions are understood as part of a private, idiosyncratic process which has its universal roots in the core relational themes of the accompanying emotions. Both are anchored in a biological evolutionary adaptation model. According to Lazarus (1991, 1999), while meaning does not emerge from the sociocultural sphere, it is certainly modified by variables within this area.

2.2 Meaning-Oriented Approaches

Lazarus (1991, 1999) abandoned the behavioral model in which mind and behavior were seen solely as a response to environmental stimuli. He suggested examining the relationship between person and environment and introduced a relational perspective. Threat is viewed as a relational meaning that “a person constructs from the confluence of personality and environmental variables” (Lazarus 1999, p. 12) and “appraisal refers to the evaluative process by which the relational meaning is constructed” (p. 13).

Park (2010) further expounded upon the conception of meaning defined in the appraisal-based coping approach: meaning-making refers to the processes people utilize in order to reduce the discrepancy between their appraised situational meaning and global beliefs and goals. It also refers to the development of explanations for varied reactions to adversity and a key distinction is between global and situational meanings. Another construct, benefit-finding, relates to the process of identifying benefits in adversity. It refers to perceptions of change as measured by self-report instruments (Pakenham 2011).

Global meaning refers to the individual’s general system of orientation. Global meanings form the core schemas through which people interpret their experience of the world. They comprise beliefs, global goals, and a subjective sense of meaning and purpose. Situational meaning is appraised in the context of a particular environmental encounter. Situational meanings focus on the question of whether a particular event is threatening or controllable as well as on the causes of the event, and any implications it might have for the future (Park 2010). According to Park (2010) , a discrepancy between appraised situational meaning and global meaning will create distress and result in an intense motivation to reduce this discrepancy through meaning-making. This process makes it possible for an individual to recover from a stressful event. Meaning-making is therefore both an automatic, unconscious process as well as an active coping activity. Automatic processes include, for example, intrusive thoughts about the stressful event and avoidance of reminders, among other things. Active coping may include identity-related appraisals. In some cases, these appraisals may lead to feelings of shame, guilt, or pride (Tracy and Robins 2004).Footnote 1

If the situational appraised meaning is changed as a result, this phenomenon is referred to as assimilation; if global beliefs and goals are changed, this is known as accommodation. The process of meaning-making implies a cognitive component (integrating experience with preexisting schemas) as well as an emotional processing component (experiencing and exploring emotions). The foundation for viewing changes in the external situation versus internal changes to the individual was already established in the distinction between problem-focused versus emotion-focused coping (Lazarus and Folkman 1984) . However, in the recent conceptualization, meaning—along with emotion—assumes a more important role. Brandtstädter (2006), Leipold and Greve (2009), and Brandtstädter (2011), for example, expanded the relationship between accommodation and assimilation into a dual-process model of developmental regulation. Given the dramatic changes to the environment, accommodative processes are critical, meaning that individuals’ life goals are modified to correspond with the actual situation.

Park (2010) points out that the mere search for meaning in the face of a catastrophic experience may not necessarily be beneficial to the health of the individual. Rumination may involve repetitive thoughts that introduce negative emotions without identifying a solution. The deciding factors are the products of the meaning-making process (meanings made). These meanings result in the subjective sense of having made sense. This may include a feeling of acceptance, a perception of growth and positive life changes, as well as the integration of the event into the identity of the individual. Park (2010) states that while there are complex constructs of meaning in theory, the operationalization of meaning-making efforts and meanings made tend to be rather simplistic. Although one of the central assumptions is that highly stressful events cause a shattering (Janoff-Bulman 1992) of the general orienting system and global meaning, there is little evidence to indicate that this shattering actually takes place. However, “it is clear that meaning-making attempts and meanings made are reported by most individuals facing highly stressful events” (Park 2010, p. 290) .

Examples of Meaning-Making in the Context of Disasters

Garrison and Sasser (2009) conducted a qualitative investigation of benefit-finding and meaning-making in families who recovered from the impact of Hurricane Katrina and were able to return to their houses . In their study, a number of different factors were included under the heading of benefit-finding: improved relationships within the family, insight into the importance of building relationships with people rather than objects, and pride about successful coping. The study found that sense-making resulted in the insights that “everything has a reason” (p. 118) and that the “storm taught us to see the important things” (p. 118). Attribution to a higher power could mean that “God had his reason” (p. 118; reference to God by 37 % of respondents) or that respondents “interfered with mother Nature” (p. 118). Less than half of the interviewees expressed a “general acceptance” (p. 118) of the storms. Additionally, most of the respondents expressed optimism with regard to their futures and the authors found that humor played an important role in meaning-making.

One interesting question inquires as to whether such challenges can be accepted as mixed experiences. The Western model is one in which the aim is to reduce negative emotions and increase positive emotions. In contrast, Eastern or Asian approaches to emotions often allow for mixed emotional experiences, which combine both positive and negative aspects, to be accepted without attempting to unify these aspects or reduce negative emotions. This acceptance may make it easier to cope with the range of personal and social experiences inherent to the most difficult of circumstances. It is still unclear whether research on stress and disasters supports this view on mixed emotions (what Miyamoto et al. 2010 and Miyamoto and Ryff 2011 call dialectical emotions).

In a similar study on the subject of faith, crisis, coping, and meaning-making conducted by Marks et al. (2009), four different age groups were compared in order to draw conclusions about the relationship between disaster and psychological development. Respondents in the younger age groups (average age 37–54) viewed the storm Katrina that occurred 3–6 months and 6–14 months prior to the study primarily as a crisis (in the sense of a developmental challenge or turning point), while respondents from the older age groups (average age 74–91) tended to view the storm as an additional life experience. Respondents attributed the storm to God and “Mother Nature.” One prevalent idea was that hurricanes served as a lesson in humility from which people had to learn to accept a lack of control. However, it is striking that both religious and nonreligious respondents shared the view that it is important to do their best in the face of their struggles and, ultimately, to make the best of the situation .

2.3 Religious-Oriented Approaches

Religious coping has two contrasting dimensions: It not only can be seen as a specialized type of meaning-oriented approach to coping, but also represents far more than a search for meaning in situations of stress. Religious coping is often associated with special types of social integration; it is also related to the idea of social support. Orientations, beliefs, and practices associated with spiritual or religious life exert a significant influence upon the appraisal processes and coping strategies.

Spirituality is generally defined as an introspective, individual experience while religiosity describes a community experience. These two ideas are related, rather than being independent constructs. Through a combination of both constructs, individuals are able to seek support from a divine being as well as from other members of a religious community, make meaning in the face of distressing events, and ultimately promote resilience, healing, and well-being (Bryant-Davis et al. 2012).

According to Pargament (2011) , religion adds a distinctive dimension to the coping process. In his view, religion is the search for significance in the sacred (Pargament 2011) and “religious coping is a search for significance in times of stress” (Pargament 1997, p. 90) . The sacred is the common denominator in both religious and spiritual life. It represents the most important objective sought by religious-spiritual individuals, and, as such, is tightly interwoven in the course of their lives (Hill and Pargament 2008). Sacred refers not only to God and higher powers, but indeed to any element that is tied to God and therefore “imbued with spiritual qualities like transcendence, boundlessness and ultimacy” (Pargament 2011, p. 272).

The idea of a universalist conception of religiosity, which is independent of contextual and cultural associations and serves as a universal property of humanity, blossomed in the 1980s and 1990s in line with the development of a number of instruments for measuring religiosity (see Hill and Hood 1999). Pargament (1997, 2011) and Pargament et al. (2000) postulated that, during stressful life events, common religious beliefs can be translated into specific methods of coping. They not only showed how different religions opt for different systems of coping, they also demonstrated how the same religion, applied to different cultural contexts, might stimulate completely different methods of coping with painful and difficult life events. Pargament (1997), like Park (2010; see earlier discussion), states that people bring their own personal orientation systems to bear on stressful situations. This orientation system is the special way in which a particular individual perceives and interacts with the world: “It consists of habits, values, relationships, generalized beliefs and personality” (Pargament 1997, 99 f.) . Religious orientation makes up a part of this comprehensive orientation system. The culture helps to shape the coping mechanism and is itself reshaped by these forms of coping. However, Pargament’s universalist, person-centered approach makes only minor concessions toward relativizing the culture-specific differences between the world religions.

According to Pargament (2011), every religious coping effort has a common end, that is, to enhance significance. This can be done by conserving or transforming significance. With conservation, the emphasis is on protecting or maintaining that which is of significance. With transformation, significance is maximized by attempts to change the nature of significance itself (Pargament 1997). This concept is very similar to the ideas of assimilation and accommodation used in the meaning-making approach (see Park 2010) as well as to the developmental approaches to coping (see Leipold and Greve 2009). According to Pargament, transformations take place only on an individual basis within the religious belief systems. Believers first seek to interpret the events they encounter in ways that allow them to conserve and confirm their existing meanings. It is only in extreme situations that they then seek to modify or transform the beliefs that make sense to them (for example, in the case of conversion or disavowal of previous beliefs).

The search for meaning filters and influences the interpretation of the situation. The system of religious beliefs, which is in turn a part of the general person-specific belief system, mediates between the situation at hand and the solution to the problem. Pargament portrays this accepted religious belief system (insofar as it is related to coping) as an array of opinions that are shared to variable and measurable degrees by the adherents of that system.

Difficulties arise in the religious coping approaches when it comes to gaining mastery and control because one subcategory of religious coping is relinquishment of control. Cole and Pargament (1999) discuss the paradox of the phenomenon of spiritual surrender in which people do their best while still relinquishing control to the higher being. They see this phenomenon as a universal response offered by many religions as an answer to human limitations. As part of this practice, person-centered control itself is surrendered in order to attain emotional and spiritual objectives (Cole and Pargament 1999). We believe that the authors transcend the cognitivist coping model (see Sect. 2.2.1) when they write, “spiritual surrender is much more than a cognitive shift. It is an experiential shift as well, one that involves changes in motivation, affect, values, perception, thought, and behavior” (p. 185).

According to Pargament (1997), the most helpful varieties of religious coping are those associated with a perception of God as supportive and feelings that God is loving and should be trusted to care for one’s burdens. Perceptions of God as benevolent are particularly beneficial for coping. For some people, perceptions of a partnership with God are advantageous, and many derive strength from their religious communities. The social support they receive can ease the burden of coping. Overall, those aspects of religious coping were the only ones Pargament considered to be generally advantageous. Other forms of religious coping such as pleading—that is seeking control indirectly by pleading to God for a miracle or a divine intervention—appear to have either mixed or predominantly negative effects (similar to the view of God as punisher).

2.4 Future-Oriented Coping

Future-oriented coping is founded on the basic theoretical assumptions of the appraisal-oriented model introduced in this chapter and refers to an individual’s strategies for handling future threats and challenges. In this respect, this type of coping represents one psychological approach to risk management. We addressed the collective dimensions of the topic of disaster risk in Chap. 1. We determined that it is difficult to assess the sociocultural-specific ways in which individuals handle risk using existing universalist models.

In the psychological coping research, future-oriented behavior was primarily analyzed in the context of individual health threats. Psychological models were developed with the aim of achieving universal validity. In the field of health promotion, there are both collective and individual strategies for handling risk. In a Western context, there is a heavy focus on the latter approach as well as on the rational control paradigm . It is with this in mind that Schwarzer et al. (2003) formulated the individual stages of the motivational and volitional process in their health action process model.

In the case of both disaster risk management and health-related action, there is still only a tentative relationship between the perception of a risk and the practical action taken to counter this risk. The assumption is that there are a series of universal psychological mechanisms that prevent precautionary behavior. Slovic and Västfjäll (2010) have shown that intuitive action in risk situations can lead to confusion and irrational behavior. Gigerenzer (2008) and Kahneman (2011) analyzed the weaknesses (and strengths) of risk heuristics and demonstrated that it is extremely difficult to weigh up multiple risks simultaneously. Because the perception of a potential threat causes unpleasant feelings, the individual turns to the process of wishful thinking (Lazarus and Folkman 1984) . As a result of this process, the individual begins to assume that the threat is not serious or that he or she will not be affected. This corresponds to what is referred to as the optimism bias in risk perception (see Chap. 1). In some cases, a positive illusion in the form of unrealistic optimism was identified (that is, situations in which people believe they will be personally immune to a disaster, such as an impending earthquake; Burger and Palmer 1992). In another strategy, the individual associates any potential effects of the threat with external conditions rather than with his or her own behavior.

On a theoretical level, there are different conceptions of future-oriented coping known as proactive coping , that is, a “process of anticipating potential stressors and acting in advance either to prevent them or to mute their impact” (Aspinwall 2011, p. 334). In their conceptualization of proactive coping, Aspinwall and Taylor (1997) and Aspinwall (2011) propose a five-step model of future-oriented coping. This process starts with a general move toward resource accumulation. The process continues with the identification of potential stressors, the initial appraisal of their potential for threat, and the regulation of any accompanying negative emotions. Preliminary coping efforts are focused on relieving or diminishing the effect of the stressor as well as eliciting feedback and using it to regulate the initial appraisal and preliminary coping efforts. Proactive coping as an individual endeavor has mainly developed in the context of threats to health; however, it has also been extended to threats in the fields of work, aging, and social relations. Although Aspinwall (2011) suggests that proactive coping should be extended to stressors in dyadic relations or families as well as to large-scale collective proactive coping problems, this theoretical framework has yet to be developed.

Schwarzer and Taubert (2002) propose a different, more differentiated terminology. Their terminology takes into account not only the timeline of the threat but also the certainty (or uncertainty) of the risk. This is an important dimension in the context of disasters because some disasters such as earthquakes develop rapidly and the effects are unpredictable. In this model, along with reactive coping, which relates to an event in the past, there are three additional forms of coping: preventive coping, anticipatory coping, and proactive coping. With preventive coping, a critical event may or may not occur in the distant future. This type of coping is associated with uncertainty and requires the management of unknown risks. This model corresponds to Aspinwall’s (2011) definition of proactive coping. Anticipatory coping refers to a certain, imminent threat. In contrast, the concept of proactive coping proposed by Schwarzer and Taubert (2002) is not directly associated with a threat; instead, it is an “effort to build up general resources that facilitate promotion toward challenging goals and personal growth. In proactive coping, people have a vision” (p. 28). In this reading of proactive coping, future-oriented behavior is not dependent upon a threat. Goal management, rather than risk management, is central to this understanding. The focus of self-regulatory goal management is an active engagement with challenges and “ambitious goal setting and tenacious goal pursuit” (p. 29). Schwarzer and Taubert (2002) therefore categorize lifestyle choices characterized by active, future-oriented planning and accumulation of resources as coping behaviors.

In positive psychology, future-oriented behavior has increasingly been conceived of as separate from risk and threat. In this field, eustress is conducive to development and perceived as a positive challenge. If we view the selection and accumulation of skills and resources as strategies for self-regulatory goal management in the process of individual striving, the individual’s stock of resources will make the individual more resilient in the event of a disaster. However, to date there has been little research on the relationship between the cultural context, and environments with fewer resources, and an individual’s perceptions of the future.

Future orientations can be viewed as a part of future-oriented coping and developmental psychology as well. In these fields, they are understood as multidimensional processes that combine motivational, cognitive, and behavioral components (Kotter-Grühn and Smith 2011; Seginer 2008). Future orientations tend to be associated with hope, even under stressful circumstances, and, according to Seginer (2008), these attitudes comprise both culturally specific as well as universal components. Seginer shows that individuals who are part of collective societies (see Sect. 2.4) are able to draw upon the goals of their community as a reservoir of communal or religious ideologies that have been practiced since childhood. In contrast, individuals from individualistic societies have less community-based support and must find and pursue their own personal goals.

Resilience has come to serve as a bridge concept between episodic periods of coping and the lifelong objective of human development. Leipold and Greve (2009) understand development as “the maintenance and implementation of the individual’s abilities to use regulation processes to adapt to a challenging situation” (p. 42) and resilience as “successfully overcoming adverse developmental conditions” (p. 40). Following Brandtstädter (2011), there are two equivalent transformation processes working in tandem as part of episodic coping and lifelong development: the first is an intentional, personal assimilative mode in which the individual’s life situation is brought into alignment with his or her expectations and goals. The second is a sub-personal accommodative mode which involves revising standards and goals to suit the given possibilities for action. According to Brandtstädter (2011), neither mode has primacy. He criticizes prior coping research, which, in his view, focuses mainly on the persistent pursuit of goals while neglecting the accommodative processes. Leipold and Greve (2009) limit intentional, planned agency by viewing the entire accommodative mode as sub-personal, that is, as a regulation process that takes place partially outside of the individual’s personal control, and which, to some extent, is not accessible to the individual on a conscious level. Accommodative processes are necessary when a threat is unavoidable or when a challenge cannot be faced; they play an important role in the individual’s ability, for example, to successfully handle the aging process. Developmental psychologists have shown that older individuals modify their life goals and meanings in such a way as to create a kind of well-being paradox: in spite of their limited opportunities (and potential illness), they are relatively content with their lives (Baltes 1997; Kotter-Grühn and Smith 2011).

2.5 Impacts of Extreme Stress on Mental Health

Following the changes in general coping theory and research, there also has been a considerable shift in the perspective on the impacts of extreme stress on mental health. In the beginning, the field of disaster psychology (see Reyes and Jacobs 2006) was identical to the fields of mental health disorders after a disaster and trauma psychology. Since the 1990s, there has been a gradual expansion in the perspective which focuses on the diversity of human responses to extreme stress. Prior to that development, this diversity was buried in trauma discourse, which, with the introduction of the posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) diagnosis to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM III 1980) by the American Psychiatric Association, dominated the psychological research and practice of the time (see Bonanno et al. 2010) . The reemergence of this diversity focused on the following aspects:

-

Typically, there is a considerable amount of diversity in the longitudinal trajectories of responses to stress including resistance, resilience, recovery, and delayed and persistent dysfunction (Norris et al. 2009) .

-

Severe manifestations of problems are observed only in a small percentage of exposed individuals (Bonnanno et al. 2010).

-

Aside from PTSD, disasters may result in other psychological problems such as depression, anxiety, grief, stress-related health problems, substance abuse, and suicidal behavior (Bonnanno et al. 2010)

-

There is a cultural specificity in responses to extreme stress. These were studied as idioms of distress or cultural syndromes , triggering a discussion about the cross-cultural validity of PTSD (Hinton and Lewis-Fernandez 2011).

The concept of trauma originated in the context of the two world wars. Extreme suffering was then designated as PTSD in the American diagnostic system (DSM III, then IV and V), thereby laying claim to universal validity. One prerequisite for a PTSD diagnosis is a clearly defined traumatic event. A traumatic event in this sense implies an exposure to a threat of death or grievous bodily injury directed toward an individual or another person. Symptoms of this syndrome include intrusive distressing memories, dreams and flashbacks of the traumatic event(s), and distress at exposure to trauma-related triggers. Additional criteria include negative changes to cognition, mood, arousal, and reactivity. Disturbances cause significant distress and impairment of function which persists for longer than 1 month.

The categorial illness or disorder systems utilized by international classification bodies require universally applicable divisions between sick and healthy individuals. With PTSD, however, the assumption tends to be that there is no qualitative difference with respect to normal processes. According to Bonanno et al. (2011), PTSD is best understood as a continuous dimension and the “specification of a diagnostic cut-point will always be arbitrary to some extent” (p. 513).

The universally constructed psychological explanations take different disruptions in memory (Brewin 2011) as well as emotional and cognitive processing into account (Foa and Rothbaum 1998; Ehlers and Clark 2000; Steil et al. 2003). However, according to Pitman et al. (2012) and Schmahl (2009), the field has yet to identify the definitive disorder model. On a phenomenological level, in the psychiatric literature (for example, Friedman et al. 2011) it has been proven that exposure to a wide variety of different traumatic events (disasters, violent experiences resulting from war, accidents, and rape) results in the same consistently identifiable pattern of disturbances (ensuring coherence and reliability of PTSD identification).

In their broad overview of the costs of disaster for individuals, families, and communities, Bonanno et al. (2010) showed that the psychological cost for survivors (especially the number of PTSD cases) had been overestimated in the literature, whereas the broader impact in other areas had been underestimated. Norris et al. (2002a, b) and Norris (2005) published a comprehensive review and meta-analysis of the empirical literature and concluded:

Samples were more likely to be impaired if they were composed of youth rather than adults, were from developing rather than developed countries, or experienced mass violence (for example, terrorism, shooting sprees) rather than natural or technological disasters. […] Within adult samples, more severe exposure, female gender, middle age, ethnic minority status, secondary stressors, prior psychiatric problems, and weak or deteriorating psychosocial resources most consistently increased the likelihood of adverse outcomes. (Norris et al. 2002a, p. 207)

Bonanno et al. (2011) estimate that 5–10 % of individuals exposed to these conditions developed a PTSD. If the exposure is particularly intense and persists over an extended period of time, the rate may increase, although it seldom rises above 30 %. Hobfoll (2011) , on the other hand, disputes these figures and criticizes the “initial optimism about how many people are resilient in the face of major stress” (p. 128) with references to the high numbers of mental health problems found in his study of distress during the ongoing terrorism in Israel (Hobfoll et al. 2012). Bonanno et al. (2011) argue that most studies that demonstrate higher numbers of PTSD involve the faulty application of diagnostic methods by emphasizing average differences in a number of symptoms between exposed and nonexposed groups, for instance. Other mental disorders, problems, or impairments may accompany PTSD or become dominant disorders. These phenomena may include grief, depression, anxiety, stress-related health problems, increased substance abuse, and suicidal ideation. The more serious occurrences of these problems tend be under 30 % of a population directly affected by a potentially traumatic event (Bonanno et al. 2010).

The decisive turning point in the study of the psychological repercussions of disasters was proposed by Norris et al. (2009) and Bonanno et al. (2010). Their approaches no longer rely on the frequency of identified cases of illness following a disaster; instead, they focus on the analysis of longitudinal and other trajectories of successful or unsuccessful adaptation in the wake of a disaster. In this approach, resistance is equated with no dysfunction, resilience with a transient perturbation for several weeks, and recovery with dysfunction followed by a return to pre-event functioning (Bonanno 2004). Symptoms may display a cyclical course or emerge after a considerable amount of time (Norris et al. 2009). In chronic dysfunction, the initial stress reaction persists.

This thinking along the lines of trajectories resulted in a theoretical and methodological shift in research on the psychological consequences of disasters (Bonanno and Mancini 2012) . Specifically, Hobfoll (2011) demonstrated that PTSD is not necessarily accompanied by dysfunction:

People may experience distress and disease and yet remain committed and absorbed in their life tasks as parents, partners, workers, citizens, and friends. (Hobfoll 2011, p. 128)

The concept of posttraumatic growth (PTG) focuses on the ostensibly counterintuitive and paradoxical finding of apparent gain as a result of the negative experience, that is, that people may experience a significant positive change in life and new meaning (Tedeschi and Calhoun 2004) . In the field of positive psychology (Snyder and Lopez 2011), this phenomenon is viewed in terms of its positive effects:

Posttraumatic growth is the experience of positive change that occurs as a result of the struggle with highly challenging life crises. It is manifested in a variety of ways, including an increased appreciation for life in general, more meaningful interpersonal relationships, an increased sense of personal strength, changed priorities, and a richer existential and spiritual life. (Tedeschi and Calhoun 2004, p. 1)

The processes that occur after an experience of extreme stress are now viewed as diverse phenomena and are no longer focused on disease and dysfunction. Research on resistance, resilience, and adaptability has enabled stronger connections to be established between coping concepts and the topics of development and future orientations. However, many studies equate a decreasing severe-to-moderate symptom trajectory with resilience (by Norris et al. 2009 or by Hobfoll et al. 2008) , meaning that it is defined from a negative, rather than a positive, standpoint. In addition, studies also often refer to partial or subliminal PTSD, thereby increasing pathologization as well as the need for individual therapy (Young 2006). We address different cultural understandings of human suffering and other responses to disasters in Chap. 3.

3 Individual Coping Within Social Contexts

When researching human responses to disasters, the disciplinary context influences the formulation of the research question and determines the form of investigation: The mainstream psychological approaches referenced in Sect. 2.2 focus on identifying generalizable rules which are rooted in human mental structures and reflected in social behavior . The individual is the focal point. From a social science perspective, the approach is reversed. The goal is to determine the extent to which individual experiences and actions are affected and produced by sociocultural conditions and topics. Models that rely on a complex interplay—or a reciprocal structure—between the individual and the social represent a synthesis between mainstream psychological models and social science-based models. These models are examined in Sect. 2.4.

Only a few of the psychological approaches focus more on context and emphasize the social embedding of individual behavior, although constructs such as social support and social conflict are becoming influential. In the theoretical approaches by Hobfoll (2001, 2011) and Hobfoll and Buchwald (2004), the conservation of resources theory, coping is explained primarily from the viewpoint of human nature. However, in his integration of real sociocultural and material conditions, Hobfoll demonstrates that the stress process must be understood as a complex set of interactions between these elements.

3.1 A Resource-Oriented Approach

The stress coping theory proposed by Hobfoll (2001, 2011) , Hobfoll and Buchwald (2004), and Hobfoll et al. (2011) focuses on the objective elements of threat, loss, and common appraisals rather than subjective, idiographic appraisals. In this way, they ensure that exclusive focus is not placed on the individual and prevent the theoretic–analytical dissociation of the individual from his or her sociocultural and material contexts. The theory is based on the premise that human beings will strive for resource gains, that is, for things they value most highly. Value is attributed to resources based on the specific cultural context. These resources may be considered worthy in and of themselves or because they promote the retention or acquisition of other resources :

Resources include object resources (for example car, house), condition resources (for example employment, marriage), personal resources (for example key skills and personal traits such as self-efficacy and self esteem) and energy resources (for example credit, knowledge, money). (Hobfoll 2011, p. 128)

The list of particular resources mirrors the diversity of cultural settings with their individualistic and collective ideals. Hobfoll (2001) uses a cultural term with a hierarchical structure of individual-nested and family-nested in tribe. Here, he is referring to Boas (1940).

Resource loss is an important component in the stress process, and it receives a disproportionate amount of emphasis in comparison with resource gain. This principle is known as loss primacy. The second principle—termed resource investment—is future oriented. This principle posits that individuals invest resources in order to protect themselves from loss, recover from loss, or acquire new resources. This process results in a pool of resources which Hobfoll terms resource caravans. Families and individuals are dependent upon resource-enriching environments; otherwise “they fail to develop their resource caravans mainly out of circumstances that are beyond their and their families’ control” (Hobfoll 2011, p. 129). Those who possess resources are more capable of gain, and this leads to further gain. However, loss cycles will be more influential than gain cycles. If the loss of resources continues, individuals become increasingly vulnerable to the effects of stress and fall into a spiral of loss, a process that can have serious consequences. In situations of loss, a paradoxical, opposite process comes into play; here, the salience of gain increases in situations of resource loss. This process, which Hobfoll (2011) refers to as third principle, is reported to play a role in traumatic situations and resiliency efforts .

The Conservation of Resources (COR) theory is less an input–output model of coping with stress than a model for the commerce of stress and resources within social contexts. In this model, both successful and unsuccessful adaptation may occur. In this broader context, the episodes of coping are viewed as adaptation processes. In Hobfoll’s model, social support is a valuable resource which is closely related to resiliency. The theory offers an understanding of coping that sees individualistic and communal coping as a continuum:

We need to widen the social aspects of coping efforts and move from self-regulation to self-in social settings regulation. (Hobfoll 1998, p. 130)

According to Hobfoll (1998), there is a stress crossover between individuals within the community; that is, the stress experienced by one person influences the stress experienced by another person, a partly involuntary sharing of resource loss. He also analyzes the dynamics of intragroup stress and the different demands within the community (between those who are stronger and those who are weaker in the group or community). In addition to stress crossover, there is also a transfer or crossover of resources. Hobfoll and Buchwald (2004) explain the common sharing of resources by describing the barriers between different individuals within a community to be more or less permeable.

He does not use a typology to represent the different ways of coping. Instead, he relies on a multiaxial model in which individuals are characterized by their position along the axes. On the first axis, we find the degree of coping activity; this axis spans from very active, through cautious action, to passive avoidance. The second axis represents the dimension of prosocial versus antisocial coping. In prosocial coping, the individual seeks social support and mutual cooperation. In antisocial coping, the individual strives to obtain advantages at the cost of others. On the third axis, which incorporates findings from Japan, a country representing rather inter-connected selves, besides American findings representing predominantly autonomous and independent selves, Hobfoll introduces a distinction between direct and indirect coping strategies. Indirect action is often found in communities that strive to maintain harmony. It is a diplomatic–strategic form of action. An individual acts in such a way as to disguise the intentions of this action from his or her interaction partner. This way, the individual will not lose face if he or she makes a mistake (Hobfoll 1998) .

According to Hobfoll (1998), the COR theory can incorporate the idea that coping actions represent not only individual but also collective actions: In this model, actions are embedded in a historical and cultural context, and assessments are not made independently by single individuals, but in fact represent large-scale perceptual and interpretive structures that are shared within the community . This applies to the perceived meaning, relevance, and threats associated with a particular situation as well as to the perception of the individual coping efforts and, in particular, the collective coping efforts, surrounding the situation .

3.2 Social Support and Social Conflict

The concept of social support has also begun to draw more attention in mainstream psychology; however, it is important to note that the different approaches to stress each incorporate different conceptualizations of social support :

[Social support] may be regarded as resources provided by others, as coping assistance, as an exchange of resources, or even as a personality trait. Several types of social support have been investigated, such as instrumental or tangible (assist with a problem, donate goods), informational (give advice), and emotional (offer reassurance, listen empathetically). (Schwarzer and Knoll 2007, p. 244)

Social support was integrated into the appraisal-oriented stress approaches and assumed a functional role as one resource factor. Evidence from studies in the field of individual health and illness shows that support has an indirect enabling effect on coping. It increases perceived self-efficacy, which in turn improves an individual’s potential to obtain support from social networks. In dyadic relationships, Schwarzer and Knoll (2007) observed a resource transfer from the individual providing the support to the individual receiving it. In the approach proposed by Schwarzer and Knoll, when considering coping in couples in which one partner suffers from severe illness, the focus lies not on the shared process of coping with a severe illness, but rather on the ways in which the sufferer perceives the support provided and the effectiveness of this support. In this respect, an individual’s subjective appraisal remains as the dominant function in appraisal-oriented coping .

However, divergent interests and social conflicts are difficult to model from a social support perspective. Hobfoll (1998) states that the availability of social support is dependent upon power and status. According to him, certain people are nested in settings which offer them rank and privilege. Those lacking in status and power suffer social discrimination almost independently of their own behavior. However, those with power, status, and privilege are faced with developmental conditions—Hobfoll refers to these as “caravan passageways” (Hobfoll 2011, p. 129) —which lead to social exclusion. The concept of passageways can be extended to neighborhoods, work environments, and other contexts. These passageways are responsible for an individual’s access to cultural capital, material goods (for example, inheritance), and social support. The mastery and self-efficacy attributed to individuals is therefore viewed as a function of their positions in a privileged passageway for their resource caravans (Hobfoll 2011). The individual’s ability to seek social support is dependent upon the availability of this support in a real context, a factor which tends to be neglected in the various appraisal-oriented coping approaches .

The concept of social support has influenced the practice of disaster psychology, that is, interventions to prevent PTSD by education about what to expect rather than reliving the experience such as was the case in critical incident stress debriefing. Kaniasty and Norris (1993), Norris et al. (2005), and Kaniasty (2012) developed a model to illustrate how different subgroups of disaster survivors experience social support or a lack thereof. This model is connected to Hobfoll’s COR theory . The authors differentiate between the constructs of social embeddedness (quantity and types of relationships with others), received support (actual receipt of help), and perceived support (the belief that help would be available if needed).Footnote 2 Specific properties of the disaster, such as severity of exposure and displacement as a result of the disaster are relevant to the social support dynamics in coping efforts. The authors proposed a social support deterioration model (Kaniasty and Norris 1993) that they continued to develop over a series of studies on different disaster types (for latest results, see Kaniasty 2012). The model aims to generate general predictions about the dynamic social processes at work after disasters. It links both social support and social conflict with factors such as distress , trauma, and well-being. The model starts with the often-reported finding that "natural" disasters elicit the provision of widespread mutual aid and support. The social support deterioration deterrence model predicts that the experience of having received social support in the initial period of solidarity will distort the perception of reality in which social support is actually deteriorating. According to the model, this exaggeration of perceived available support is the reason behind feelings of well-being or reduced distress and pathology. Postdisaster social bitterness may emerge due to dissatisfaction with aid, social support, interpersonal constraints, and conflicts, leading to increased distress and pathology (Kaniasty 2012) .

The sociological approaches to social conflicts and the resolution of these conflicts are more generalized :

Social conflict [is] a struggle over values or claims to status, power, and scarce resources, in which the aims of the conflict groups are not only to gain the desired values, but also to neutralize, injure, or eliminate rivals. (Coser 1967, p. 232)

In conflict resolution theory and practice, there is an ongoing discussion about the universality or cultural specificity of ideas of fairness and justice (Deutsch 2000). The crucial factor in postdisaster settings is distributive justice:

[It] is concerned with the fair allocation of resources among diverse members of a community. Fair allocation typically takes into account the total amount of goods to be distributed, the distributing procedure, and the pattern of distribution that results. (Maiese 2003)

Wagner-Pacifici and Hall (2012) see the issue of power as a crucial aspect in conflict resolution. Preconflict power relations also factor into postdisaster dynamics. The authors point to the difference between the resolution of a conflict and mere end of the conflict. Both concepts may play an important role in postdisaster conflicts (especially in dealing with possible conflicts along the helping process) as part of the long-term communal process of coping with disaster. The authors question whether reaching a resolution is always desirable. In their introduction to the approach of conflict transformation utilized by Mahatma Gandhi, Kurtz and Ritter (2011) write :

Resolution carried with it a danger of cooptation (Gleichschaltung), an attempt to get rid of conflict when people were raising important and legitimate issues.

Reconciliation processes may also mean that people are no longer given a position to air their grievances. People may be expected not to raise issues of injustice anymore which helps to maintain the status quo instead of allowing for renegotiation for a more just social system. While, for some, participating in reconciliation practices may generate solidarity and even community pride which, in turn, affords healing, others may feel excluded or more isolated .

4 Coping as a Social Process

The individual-subjective perspective in psychology has been transgressed primarily as a result of Hobfoll’s COR theory (see Sect. 2.3.1). Feelings of stress as well as access to and control over resources all have a collective dimension. The goal is to understand the reasons why as well as how communal coping strategies and prevention measures develop. Hobfoll continues to emphasize the importance of social and gender-related inequalities rooted in the power dynamics within a given society and their effect on an individual’s access to and control over resources and opportunities to develop a resource pool. With this notion, he sketches out the sociocultural and material boundaries of human agency. However, to what extent is the current international scientific discourse on coping and related methods itself a cultural product with a Western cultural bias? And to what extent do culture- and gender-specific biases exist in the psychological concept of coping (see Sect. 2.4.1)? In the section that follows, we address a possible synthesis between mainstream psychological models and social science-based models. This synthesis takes the form of complex interactions or reciprocal structures between the individual and the social. These models are addressed in the Sects. 2.4.2 and 2.4.3.

4.1 Biases in Psychological Coping Approaches

Certain types of action and experience are ignored in the mainstream psychological coping theories (see Sect. 2.2). The value—or lack of value—attributed to certain elements based on cultural or perspective-based biases tends to remain hidden, rendering these judgments difficult to address or criticize.

4.1.1 Androcentric Biases

Based on the models illustrated in the previous sections and the corresponding quantitative measurement instruments, there are significant gender differences that may hint at an androcentric bias . For example, women report more somatic and posttraumatic stress symptoms than men (Zeidner 2006). The lifetime prevalence of PTSD among women is also twice that among men (Breslau 2001; Kimerling et al. 2002).Footnote 3 This higher prevalence among women is reported to be independent of the type of traumatic event (Norris et al. 2002b) as well as the cultural background (Norris et al. 2002a) and age of the subject (Kessler et al. 1995). Norris et al. (2002a) also found that women are twice as likely to develop PTSD after a disaster-related experience. On a similar note, Rubonis and Bickman’s (1991) meta-analysis demonstrates that women show higher levels of PTSD symptoms and more pronounced affective responses to disaster-related experiences.

Research has shown that women tend to have larger social networks; in addition, they are more willing to offer social support (Schwarzer and Leppin 1989; Kessler et al. 1995) and more likely to implement social strategies when coping with a problem (Thoits 1991; Ptacek et al. 1994). Women rely less on direct strategies and more on prosocial coping (Hobfoll and Buchwald 2004) . According to the transactional model, emotional coping is less effective and offers fewer health benefits in comparison with problem-focused methods (Billings and Moos 1981). A number of different studies show that women tend to focus on the emotional aspects of a problem and engage in avoidance behaviors as part of the coping strategy (Billings and Moos 1981; Araya et al. 2007). These empirical findings have been used, for example, as an explanation for the fact that women are more likely to suffer from depression (Aneshensel and Pearlin 1987). Men’s emotion-focused coping strategies, on the other hand, frequently take the form of aggression against third parties or drug and alcohol consumption (Carver et al. 1989) .

Hobfoll et al. (1994) demonstrate the impact of perceived control over one’s own life on the coping process: If the individual has a higher level of perceived control, he or she tends to be more problem-focused. Men report a higher level of perceived control in comparison to women. This style of coping is associated with less psychological stress—unless the situation is completely uncontrollable (Zeidner and Hammer 1992).Footnote 4 There is also empirical evidence for gender differences with regard to the critical events that men and women experience over the course of their lives. Here it is assumed that women have been exposed to more situations in which they have had limited authority and control (Billings and Moos 1981; Geller and Hobfoll 1993; Hobfoll et al. 1994; Hobfoll and Buchwald 2004) . In contrast, Porter et al. (2000) assume that empirical differences between the genders do not actually reflect gender-specific behavior, but instead can be traced back to different memory processes based on gender role stereotypes (see also Simmons 2007; Hatch and Dohrenwend 2007).

Although different theories emerged to explain the existence of these gender specifities, the empirical research contained assumptions and references that are not immediately apparent. For example, some of these theoretical approaches are based on sociocultural factors while others are based on evolutionary biology. The latter approach is always associated with deterministic assumptions, which can pose problems from a feminist perspective. As implied by the title of the article by Tamres et al. (2002) Sex differences in coping behavior, the text focuses on the supposed biologically determined sex differences rather than on socioculturally constructed gender differences. Differences in coping are automatically accounted for based on differences in the biological sex of the individual. Generally speaking, mainstream psychological coping research usually lacks a theoretical and practical definition of gender. There are only a few authors who work to incorporate newer, feminist theoretical discussions (for example Range and Jenkins 2010; Tang and Lau 1995; Hobfoll et al. 1994; Nezu and Nezu 1987; Eisler et al. 1988).

A further problem lies in the fact that the underlying cultural understanding is not expressly stated. Western theorists proposed most of the gender theory applied in international contexts and much of the empirical research has been conducted in Western countries. It is not clear whether these theories adequately represent other sociocultural conditions.

From a feminist psychological perspective, it is crucial for theoretical models to take sociocultural and structural contexts into account instead of relying solely on individual factors. The transactional stress theory does not meet these requirements. Feminist approaches address individual problems in conjunction with institutional frameworks and societal routines (for example Mejia 2005). Without these, there is a risk of adopting an essentialist view with regard to male or female identity, and thereby reinforcing this sexual binary instead of exploring diversity. Hobfoll’s COR theory leans in this direction, as it includes the element of social embeddedness. However, only sociological approaches are able to adequately accommodate this idea .

4.1.2 Ethnocentric Biases

Markus and Kitayama (2010) suggest that psychological concepts display a Eurocentric or North American bias. Most studies have centered on individuals socialized in either a North American or Western European context. In an effort to pursue a universalist model, findings have been generalized without explicit mention of their cultural bias. Generally speaking, we can see the different Western sociocultural contexts as rather distinctive cultural contexts in which the individual person is viewed as the source of all thought, feeling, and action. These assumptions about human nature as focused on individual striving imply specific ideas about the self and human agency, ideas that are reflected in appraisal-oriented coping models.

Cultural psychologists such as Markus and Kitayama (2010) , on the contrary hand, differentiate between two types of sociality in which different modes of being or senses of self are represented. The first sense of self is seen as connected, related, or interdependent with others. In this cultural context, prescribed tasks require and encourage individuals to fit in with others, take on the perspective of others, read the expectations of others, and use others as referents for action. These interdependent relationships may be harmonious or prone to conflict. In the second model, an independent self, interaction with others produces a sense of self as separate, distinct, or independent from others. These differences between a primarily independent and a primarily interdependent self are considered to be universalist orientations that appear more or less everywhere around the world. These orientations are heavily dependent upon the social context, and, based on the given context, one or the other tends to emerge as dominant.

When the schema for self is interdependent with others and this schema organizes agency, people will have a sense of themselves as part of encompassing social relationships. People are likely to reference others, and to understand their individual actions as contingent on or organized by the actions of others and their relations with these other. (Markus and Kitayama 2010, p. 425)

In the appraisal-based coping models, which rely upon an independent self, the focus is different: In these models, individuals with a high level of self-efficacy engage in active, problem-solving control over their environment. This type of individual actively pursues social support, seeks out information, etc. The individual always remains the center of action. Even the secondary control process (in the system proposed by Skinner et al., 2003, this is referred to as accommodation) does not imply joint or less conscious action. While primary control involves influencing objective circumstances, secondary control “refers to the process by which people adjust some aspect of the self and accept circumstances as they are” (Morling and Evered 2006, p. 269). The authors stress this twofold property of secondary control and suggest that it is adaptive for coping in interdependent cultural contexts. However, developmental psychologists criticize the Western privilege of active control strategies and emphasize the importance of accommodative processes, particularly for older subjects (Brandtstädter 2006, 2011; Leipold and Greve 2009).

In their meta-analysis, Fischer et al. (2010) draw a connection between the independent and interdependent conceptions of self and religious affiliation. They analyze the relative importance of interpersonal and intrapersonal coping in Muslim and Christian faiths and connect appraisal-oriented coping with the social psychological conceptions of intergroup behavior and social identity.

The Christian core self is relatively individualistic, whereas the Muslim core self is oriented more toward the collective. As a consequence, it is hypothesized that when confronted with a stressful life event, Muslims are more likely to adopt interpersonal (collective) coping strategies (such as seeking social support or turning to family members), while Christians are more likely to engage intrapersonal (individualistic) coping mechanisms, such as cognitive restructuring or reframing the event. (p. 365)

We, however, believe that religion and cultural context are inherently interdependent and, therefore, that the construction of a global Muslim or Christian identity is impracticable.

In the mainstream psychological approaches reviewed in this chapter, when behavior is explained, the individual—complete with all related structures and functions—is the primary concern. The active, goal-striving, and appraising human being pursues his or her goals, even under adverse circumstances, or is willing to modify these circumstances if necessary.

The opposing model, in this case, would be the conception of subjectivity in the sociological theory proposed by Bourdieu. He views the social aspect as the driving force and subjectivity as a component of an individual’s habitus (Bourdieu 2002) :

When we speak of habitus, we maintain that the individual, and even the personal and the subjective, are social, collective properties. The habitus is socialized subjectivity. (Bourdieu and Wacquant 2006, p. 159)Footnote 5

On the one hand, the habitus means that the individual is not able to move independently and intentionally within a social context. He or she is confined to certain predefined principles of the social order. The social context itself is shaped by property and power relationships. On the other hand, the habitus remains an open disposition system which is subject to continuous change through new experiences. An individual’s actions are not determined solely through the internalization and embodiment of social structures; while these factors may limit the scope of the individual’s opportunities for independent action, they do not determine his or her behavior. However, the habitus represents the limits of the individual’s conscious knowledge of his or her possible agency .

Normally, the habitus corresponds with the individual’s environment. This relationship is based on the fact that the habitus is created by the environment. This approach explains the stability of orientations and opinions. On this basis, it is possible to understand the idea of local knowledge—knowledge which has influenced coping practices in "natural" disasters for generations—embedded in practical behavior as described by Bankoff (see further). However, a dramatic event such as a disaster can also modify the habitus to the point at which it no longer corresponds with reality. The individual loses his or her orientation and must engage in a conscious effort to renew and reconstruct this orientation, a process which subjects it to possible changes. Structural ritualization theory refers to these effects of disruptions and deritualization. Disasters may result in a breakdown of social and personal ritualized practices, their impacts on the societal order, and the ways people may cope with or adapt to such experiences by reconstituting old or new ritualized practices (Knottnerus 2012).

Even if this conception only partially applies, it could dramatically affect the understanding of coping by limiting the scope of conscious, planned agency. If individuals view their ideas and practical orientations for action as foregone conclusions resulting from their social environment and inherent resource differences with domination and subordination, then coping with a threat must be viewed in this context as well. With this in mind, it is necessary to focus on the types of action that express these foregone orientations. These include performative, ritual, and intuitive actions that pervade everyday social activities and help to reinforce and reproduce these principles or order. It is crucial to possess information about the orientations of the social subgroup and its position in the social power structure in order to investigate the group’s habitus (as this strongly influences opportunities for action and potential coping strategies) and gain insight into potential avenues of transformation. This may make it easier to understand the reasons why, after a disaster, it is difficult to establish a risk management strategy by means of persuasion with rational arguments (see Chap. 1 on the subject of handling risk).