Abstract

Literature suggests medication errors occur during care transition points such as hospital admission, transfer, and discharge due to multiple changes in medication regimens and inadequate communication among physicians, nurses, and pharmacists. Some of these errors result in serious harm as a result of omitted and incorrect medications, wrong medication dosage, and incorrect dosing frequency. Medication reconciliation is one the most important safety practices to reduce medication errors during these care transitions. There are five essential steps to medication reconciliation: determining a current list of medications, developing a listing of medications to be prescribed, comparing the two lists, making clinical decisions based on the two lists, and finalizing and communicating the list of medications to the patient and other clinicians. This chapter provides a case-based approach to understanding the root cause of and solutions to preventing medication reconciliation errors. In addition, key “take home” points provide the reader with a mental “toolkit” to prevent medication reconciliation errors. Throughout this chapter, suggestions for improving safety in the medication reconciliation process are provided that can be applied to any healthcare setting.

“Error is the discipline through which we advance.”

William Ellery Channing

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Medication Error

- Electronic Health Record

- Home Medication

- Computerize Physician Order Entry

- Medication List

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

A substantial body of evidence from international literature points to the potential risks to patient safety posed by medication errors and the resulting preventable adverse drug events. In the USA, medication errors are estimated to harm at least 1.5 million patients per year, with about 400,000 preventable adverse events [1]. In Australian hospitals about 1 % of all patients suffer an adverse event as a result of a medication error [2]. In the UK, of 1,000 consecutive claims reported to the Medical Protection Society from 1 July 1996, 193 were associated with prescribing medications [3]. Medication errors are also costly—to healthcare systems, to patients and their families, and to clinicians [4, 5]. Prevention of medication errors has therefore become a high priority worldwide.

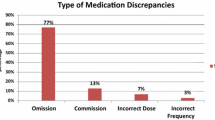

Literature suggests many of the medication errors occur during care transition points such as hospital admission, transfer, and discharge due to multiple changes in medication regimens and inadequate communication among physicians, nurses, and pharmacists [4]. In a systematic review, 54–67 % of all admitted patients were found to have at least one discrepancy between home medications and the medication history obtained by admitting clinicians, and that in 27–59 % of cases; such discrepancies have the potential to cause harm [6–8].

In response to these mounting safety concerns, the Joint Commission (TJC), in 2006, mandated that all accredited facilities must “accurately and completely reconcile medications across the continuum of care.” After careful consideration, TJC has continued to maintain medication reconciliation as a National Patient Safety Goal as of 2012 (http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/NPSG_Chapter_Jan2013_HAP.pdf). The Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI) has also incorporated performing medication reconciliation as a part of its 100,000 Lives Campaign. Another impetus for medication reconciliation is the growing interest in innovative models of care delivery, such as accountable care organization (ACO) and patient-centered medical home (PCMH) where patients have a direct relationship with a provider who coordinates a cooperative team of healthcare professionals, takes collective responsibility for the care provided to the patient, and arranges for appropriate care with other qualified providers as needed. One key element of PCMH accreditation by the National Committee for Quality Assurance is the ability to coordinate care via managing information, such as medication lists, efficiently across providers and settings, preferably using the current health information technology such as EHR. Clearly an effective medication reconciliation process would be vital to achieve a successful implementation of PCMH.

Medication reconciliation is one of the most important safety practices to reduce medication errors during care transitions and can be defined as “comparing a patient’s current medication orders to all of the medications that the patient had been taking before the transition,” e.g., comparing and reconciling admission medication orders with the home medications. To ensure patient safety, it is important to recognize that the broad definition of “medications” includes prescription drugs as well as “over-the-counter” drugs and herbals, etc., because these may have important interactions with each other. For the purpose of medication reconciliation, medications are defined by the Joint Commission as “any prescription medications, sample medications, herbal remedies, vitamins, nutraceuticals, vaccines, or over-the-counter drugs; diagnostic and contrast agents used on or administered to persons to diagnose, treat, or prevent disease or other abnormal conditions; radioactive medications, respiratory therapy treatments, parenteral nutrition, blood derivatives, and intravenous solutions (plain, with electrolytes and/or drugs); and any product designated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a drug” [9].

Recent experience suggests that inadequate reconciliation accounts for 46 % of all medication errors and up to 20 % of all adverse drug events (ADEs) among hospitalized patients [10]. Further, medication errors can be reduced by more than 76 % when medication reconciliation is implemented at admission, transfer, and discharge [11].

There are five essential steps to medication reconciliation: determining a current list of medications; developing a listing of medications to be prescribed; comparing the two lists; making clinical decisions based on the two lists; and finalizing and communicating the list of medications to the patient and other clinicians. Table 8.1 lists the steps in the medication reconciliation process in a clinical scenario where a patient is admitted from home for surgery, goes through several steps in care transitions, and is discharged home.

The goal of this chapter is to provide a case-based approach to understanding the root cause of and solutions to preventing medication reconciliation errors. In addition, key “take home” points will be presented that will provide the reader with a mental “toolkit” to prevent medication reconciliation errors.

The two cases presented in this chapter represent hypothetical cases that may occur in any hospital or ambulatory setting. Case 1 occurs in a hospital that utilizes an electronic health record (EHR) with computerized medication reconciliation; Case 2 occurs in a hospital that is partially computerized and does not have computerized physician order entry (CPOE). The summary of the root cause analyses and the solutions to prevent future error are based on “real life” discussion of a typical sentinel event root cause analysis (RCA) group formed as part of a hospital’s quality improvement process. Throughout this chapter, suggestions for improving safety in the medication reconciliation process are provided that can be applied to any healthcare setting.

Case Studies

Case 1: Digoxin Toxicity Due to Inadequate Discharge Medication Reconciliation

Clinical Summary

M.K. is an 85-year-old female with a past history of congestive heart failure (HF), atrial fibrillation, asthma, and chronic renal failure who is admitted (ADMISSION 1) with acute exacerbation of HF, fatigue, and loss of appetite. M.K.’s medications prior to admission include digoxin 0.25 mg once a day; metoprolol XL 100 mg once a day, ramipril 2.5 mg PO once a day; multivitamin 1 tab once a day, tylenol 325 mg PO four times a day as needed for joint pain, and albuterol inhaler two puffs every 6 h as needed for shortness of breath. A laboratory value of significance on admission is a serum digoxin concentration of 2.4 ng/ml (range 0.9–2.4 ng/ml). M.K’s digoxin is held, and a decision is made by the medical team not to continue digoxin in the future due to concern for digitalis toxicity. The patient is successfully treated with diuresis (furosemide, metolazone) and is prepared for discharge home where her daughter will administer her medications. Three days after hospital discharge the patient is readmitted (ADMISSION 2) with the family stating “my mother is seeing things.” A STAT digoxin level measures 3.4 ng/ml and the patient is treated with digoxin immune fab. On review of the past admission (ADMISSION 1) by the attending physician and discussion with M.K.’s family, it is found that the digoxin was inadvertently continued with the home medication regimen, causing digitalis toxicity and ADMISSION 2.

Figure 8.1 graphically depicts a timeline for this case study. As illustrated, during the patient’s hospital stay, there were several occasions where digoxin on the discharge medication list could have been reviewed, verified, and checked for accuracy.

Root Cause Analysis

The leading question for the RCA team was: why was digoxin continued at home in a patient with suspected digoxin toxicity? Fundamentally, this was a failure of the medication reconciliation process, especially at discharge and the RCA revealed the following contributing factors (1) suspected digoxin toxicity was not documented as a problem in the EHR during ADMISSION 1; (2) digoxin was “held,” and not discontinued during admission medication order entry; (3) decision to discontinue digoxin during ADMISSION 1 was not documented in the daily progress notes; (4) discharge planning discussion on ADMISSION 1 did not include medications, and there was no discussion about discontinuing digoxin; (5) family or patient were not made aware of high normal digoxin level on ADMISSION 1; (6) physician not directly related to the case was covering on a weekend when the decision was made to discharge M.K from ADMISSION 1. Therefore, the discharging physician, who was not completely familiar with the patient’s hospital course and medical history, completes the computerized medication reconciliation on ADMISSION 1 and does not notice digoxin was held; (7) nurse caring for MK provided the family with computerized discharge instruction sheet for ADMISSION 1 and did not notice that digoxin is continued.

As a result, the patient’s discharge medication list contained digoxin 0.25 mg once a day. M.K.’s family arranges medication at home according to the discharge instructions from ADMISSION 1 and resumes MK.’s digoxin.

Clearly, the fundamental failure in this patient involved inadequate medication reconciliation at various stages of transition and a lack of communication among various caregivers. Multiple healthcare professionals were managing the transitions of care for this patient and no one had the comprehensive “big picture” of the patient’s problems on ADMISSION 1. While the patient’s main problem was exacerbation of CHF, an important clinical problem was a high-normal digoxin serum concentration. The significance of digoxin level was downplayed, despite the fact that the medical team intended to discontinue the digoxin. The documentation of digoxin discontinuation was also overlooked in the EHR. During the medication reconciliation process, a covering medical resident, simply ordered the admission list of medications and added metolazone. This mistake occurred since the physician may not have properly understood or incorrectly used the functionality of computerized medication reconciliation in the EHR.

This case also represents breakdown in communication between the discharging nurse and the patient’s family. There was no discussion with the patient’s family on admission regarding concerns with digoxin; as a result the patient’s family was not aware of any problems when M.K.’s daughter restarted digoxin. Nurses caring for the patient did not notice the digoxin had not been restarted, indicating a breakdown in communication on the daily care plan. There was no communication with the patient that the digoxin was a concern. The patient was capable of understanding this information and should have been warned of the potential for digoxin toxicity.

Figure 8.2 represents the various process breakdowns that precipitated the medication reconciliation error.

Steps for Error Prevention

The most significant prevention step involves improving communication among caregivers and with patients and family so that everyone is on the “same page” in terms of the patient’s correct medication list. Additionally, improving the design and user interface of the EHR would also help. For example, the digoxin was continued primarily because the order was “held” in the computer system versus being discontinued. The system design improvement may consist of a “forcing function” upon discharge so the discharging physician must make a deliberate decision to discontinue or continue a medication. Additionally, an EHR must have interoperability such that the same medication information is available to all caregivers, and ideally a copy of the medication list is “exported” to the patient’s personal health record for access at home.

Case 2: Anticoagulant Omitted Upon Transfer to a Rehabilitation Facility Leading to PE

Clinical Summary

B.A., an 83-year-old woman, has undergone hip fracture surgery and is ordered “fondaparinux 2.5 mg subcutaneous once daily” postoperatively. Preprinted standing orders for postoperative hip fracture treatment are not available on the nursing unit when B.A returns to the floor, and the fondaparinux was written as an individual order along with other postoperative medications. B.A.’s postoperative course is uneventful, and she is transferred to a rehabilitation facility on postoperative day 3. On postoperative day 7 (day 4 at the rehabilitation center) she complains of shortness of breath, chills, sweating, malaise, and rapid heart rate, along with right calf swelling, redness, and pain. She is transferred to the hospital and the emergency room physician discovers that fondaparinux was not continued on the transfer to the rehabilitation facility. B.A. is admitted for a possible deep vein thrombosis (DVT) / pulmonary embolism (PE) from inadequate anticoagulation prophylaxis. B.A. is placed on therapeutic anticoagulation (intravenous heparin 800 units/h), venous Doppler studies prove positive for DVT, and a nuclear lung scan to detect a PE is not conclusive. After a 10-day hospital stay that is complicated by a fall, pain control issues, and difficulty in achieving a therapeutic warfarin dose, B.A. recovers fully and is transferred back to an assisted living facility.

Figure 8.3 illustrates the timeline for this event. The absence of anticoagulation for 4 days and immobility placed B.A. at risk for a postoperative DVT.

Root Cause Analysis

The primary RCA question in this case is: why was fondaparinux omitted from the transfer medication list? The RCA revealed the following contributory factors for this error of omission from the medication list (1) specific directions for fondaparinux were not included on the original postoperative order (e.g., “continue for 7 days for prophylaxis”); (2) the standard order set for hip fracture repair was not available due to supply problems at the hospital’s printer and therefore not used; (3) the admission medication list was used to create the discharge/transfer medication list; as a result fondaparinux was omitted from B.A’s discharge medication list; (4) the rehabilitation facility did not conduct a thorough medication “intake” and screening for DVT prophylaxis in B.A.; and (5) DVT prophylaxis was missed by the admitting physician as well as the pharmacist filling prescription orders in the rehabilitation center.

Figure 8.4 represents the variations in practice that caused the error in case 2.

Steps for Error Prevention

A major initiative that may possibly prevent this error from occurring in the future is the computerization of order entry. In this case, a computerized standing order for postoperative hip fracture medications would have included the duration of the fondaparinux therapy, and this order would have been included on the computerized medication reconciliation list.

Discussion

The case studies in the chapter clearly illustrate the importance of performing consistent and accurate medication reconciliation in various settings to ensure patient safety. A key to error-free medication reconciliation is obtaining an accurate history of prescription medications as well as over-the-counter products such as vitamins, nutraceuticals, and herbal products. A detailed medication history produces an accurate home medication list; this accuracy carries through a patient’s hospital stay or ambulatory course and results in an accurate medication list on any transition of care. Gathering information for a thorough medication history may be time consuming, involving phone calls to pharmacies, and other providers. Prescription claims data, sometimes interfaced with an EHR, can be used to determine home medication but adherence should be interpreted cautiously [12]. An alternative to physicians conducting the medication history includes nurses, pharmacists, medical students, and pharmacy students obtaining medication histories. Froedert Hospital in Milwaukee, Wisconsin used pharmacists to conduct medication histories and perform medication reconciliation with success [13]; an American academic medical center used nurses with the specific function of managing medications at the transition of care with success in preventing reconciliation errors [14].

Common causes of errors in the home medication list include (1) patients failing to bring the prescription bottles to the hospital or doctor’s visit; (2) limited access to vital information (e.g., labs test results.) in the care provider’s office or other care area (e.g., the emergency room) to adequately interpret the home medication list; (3) untrained or inexperienced personnel documenting the home medication list in a hospital or physician’s office; and (4) unclear labeling of home medication bottles [15].

We suggest the following key considerations to clinicians to resolve and reconcile medications on a patient’s home or hospital drug list. Does this medication duplicate any medications from the home medication list? Will prescribing this medication confuse the patient? Is this medication prescribed resulting in too many medications for the patient to accurately track and take? Poly-pharmacy, or a high number of medications for a patient, is a well-documented contributing factor to hospital readmissions [16]. The focus of prescribing medications during the hospital stay should be to simplify the discharge medication list to minimize medication errors in compliance, adherence, and self-administration. Similarly in the ambulatory setting, the focus of prescribing medications is to keep the list as simple as possible and maintain adherence and treatment goals. However, simplifying the medication list offers a unique challenge to clinicians, since a patient’s condition may be worsening, resulting in various combinations of medications and changing medication dosages and frequencies.

The two cases in this chapter demonstrate discrepancies in the discharge medication list. Proper discharge medication reconciliation requires that the physician, in consultation with other clinical team members, the patient, and their family, makes the decision to modify, continue, or discontinue hospital medications to generate the discharge medication list. Using an EHR’s functionality, medication reconciliation can be completed with a lesser risk of error. Figure 8.5 shows an example of an electronic medication reconciliation form [17]. The prescriber can choose the action (inactivate, renew, or modify) for each medication to generate the final medication list. However, the prescriber may mistakenly choose an action or not know what each action means. Using Fig. 8.5 again as an example—does the term “inactivate” mean discontinue the medication, hold the medication, or neither? Also, institutions, clinics, and physicians’ offices must have clear guidelines as to which level of provider (e.g., pharmacists, nurse, medical assistant, physician) can access the system to perform reconciliation.

Patients’ proper understanding of their medication regimen is one of the most important factors in preventing medication errors [18]. This step may be more difficult when dealing with a vulnerable population (elderly, developmentally delayed, differing levels of literacy) and will require using resources to increase understanding (e.g., pictures, patient-friendly terminology to describe the instructions). The final medication list should be shared with patients, their families, and other clinicians involved in the care. For example, in the digoxin administration error, while the discussion of the patient’s medication regimen with the daughter took place, leading questions should have been asked to include: Does this medication list look correct to you? Do you know why each medication is being prescribed? Do you have an adequate supply of each of these medications? Has your mother had any problems with these medications in the past? Discussing any of these questions may have drawn suspicion to the continuation of the digoxin.

With the growing adoption of EHRs by various healthcare organizations, electronic medication reconciliation systems are now commonplace. A study evaluating the impact of an electronic medication reconciliation system in an acute inpatient hospital found a substantial reduction in the unintended discrepancies between home medications and admission order [19]. In another study evaluating a computerized medication reconciliation system, over 60 % of those physicians surveyed felt that medication reconciliation was important, and the computerized approach to reconciliation promoted efficiency [20]. Researchers found that while compliance with medication reconciliation was not necessarily related to the functionality, or its ease of use, or availability, it was closely correlated to the prescriber’s historical compliance to medication reconciliation using a paper system. This point brings out the importance of culture and its influence in preventing medication reconciliation errors. Clinical and administrative leaders must strive to build a culture of safety where medication reconciliation is considered a key process to promote patient safety and caregivers are held accountable for failing to adhere to this safety practice.

Key Lessons Learned

-

Develop an interdisciplinary approach to obtaining a patient’s medication history by assigning specific responsibilities to gathering and documenting medication information.

-

Develop a policy and procedure for systematic review and use of a computerized (or manual) system for medication reconciliation. Special attention should be paid to approving the types of healthcare personnel allowed to conduct medication reconciliation and assign key responsibilities to complete various tasks in the medication reconciliation process.

-

Design communication notes that are shared among all caregivers. In an electronic system improve interoperability of data; in a paper system place information in a specific part of the chart.

-

In computerized medication reconciliation, design the system to minimize “free text” data entry of medications to reduce errors.

-

Involve the patient and their family in the medication reconciliation process by reviewing carefully the home medication list and assessing patient understanding with special attention to language preference and health literacy.

-

Other practical points about managing patient’s medications from home include (1) verifying medications by a pharmacist; (2) focus on high-risk patients (elderly, patients with 10 or more medications) as a priority; (3) using electronic resources to aid in drug identification. Two examples of pill identification resources can be found at http://www.rxlist.com/pill-identification-tool/article.htm and http://www.drugs.com/imprints.php.

-

Implement leadership strategies to force accountability for medication reconciliation in patient care.

References

Aspden P, Institute of Medicine (US). Committee on identifying and preventing medication errors. Preventing medication errors. Washington, DC: National Academies; 2006.

Runciman W, Roughhead E, Semple S, Adams R. Adverse drug events and medication errors in Australia. Int J Qual Healthcare. 2003;15(Suppl):i49–59.

Chief Pharmaceutical Officer. Building a safer NHS for patients. Improving medication safety. London: Department of Health, 2004. Available at http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4071443. Last accessed 13 Jul 2013.

Bates DW, Spell N, Cullen DJ, Burdick E, Laird N, Petersen LA, et al. The costs of adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. Adverse Drug Events Prevention Study Group. JAMA. 1997;277:307–11.

Vincent C, Neale G, Woloshynowych M. Adverse events in British hospitals: preliminary retrospective record review. BMJ. 2001;322:517–9.

Cornish PL, Knowles SR, Marchesano R, Tam V, Shadowitz S, Juurlink DN, et al. Unintended medication discrepancies at the time of hospital admission. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(4):424–9.

Gleason KM, Groszek JM, Sullivan C, Rooney D, Barnard C, Noskin GA. Reconciliation of discrepancies in medication histories and admission orders of newly hospitalized patients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(16):1689–95.

Akwagyriam I, Goodyer LI, Harding L, Khakoo S, Millington H. Drug history taking and the identification of drug related problems in an accident and emergency department. J Accid Emerg Med. 1996;13(3):166–8.

2010 Hospital Accreditation Standards. Available at http://www.jointcommission.org/standards_information/standards.aspxAccessed 15 May 2013.

Barnsteiner JH. Medication reconciliation: transfer of medication information across settings-keeping it free from error. J Infus Nurs. 2005;28(2 Suppl):31–6.

Rozich JD, Howard RJ, Justeson JM, Macken PD, Lindsay ME, Resar RK. Standardization as a mechanism to improve safety in health care. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2004;30(1):5–14.

Cutler DM, Everett W. Thinking outside the pillbox—medication adherence as a priority for healthcare reform. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1553–5.

Murphy EM, Oxencis CJ, Klauck JA, Meyer DA, Zimmerman JM. Medication reconciliation at an academic medical center: a comprehensive program from admission to discharge. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66:2126–31.

Vira T, Colquhoun M, Etchells E. Reconcilable differences: correcting medication errors at hospital admission and discharge. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:122–6.

Weber RJ. Medication reconciliation pitfalls. Available at http://webmm.ahrq.gov/case.aspx?caseID=213. Accessed 19 Feb 2012.

Yvonne K, Fatimah BMK, Shu CL. Drug-related problems in hospitalized patients on polypharmacy: the influence of age and gender. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2005;1:39–48.

Life as a healthcare CIO. Available at http://geekdoctor.blogspot.com/. Accessed 13 Jul 2013.

Villanyi D, Fok M, Wong RY. Medication reconciliation: identifying medication discrepanices in acutely ill older hospitalized patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2011;9:339–44.

Agrawal A, Wu WY. Reducing medication errors and improving systems reliability using an electronic medication reconciliation system. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2009;35:106–14.

Turchin A, Hamann C, Schnipper JL, Graydon-Baker E, Millar SG, McCarthy PC, et al. Evaluation of an inpatient computerized medication reconciliation system. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15:449–52.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Weber, R.J., Moffatt-Bruce, S. (2014). Medication Reconciliation Error. In: Agrawal, A. (eds) Patient Safety. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7419-7_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7419-7_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4614-7418-0

Online ISBN: 978-1-4614-7419-7

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)