Abstract

There is a two-way relationship between working in an organization and the thoughts, feelings, and actions that people experience. There is a wide range of literature on the relationship between the characteristics of the organization and the well-being of workers, as well as an extensive collection of literature on the inverse relationship between individual factors and job performance.

For instance, it is well established that the sense of identification with the organization and the self-esteem that comes from being part of it is important in predicting a wide range of work-related attitudes, behaviors, and context variables. Self-esteem is a protective factor against negative affectivity and work-related stress. It is less clear which mechanisms regulate the interaction between organization-based and global self-esteem and how they might affect the well-being experienced in the workplace by workers, especially in times of downsizing and increasing job uncertainty.

This chapter considers the relationship between global (self-based) and organization-based self-esteem in times of job insecurity. The literature reviewed within this chapter seems to suggest a somewhat direct relationship between them. It is reasonable to argue that in times of job insecurity (i.e., if a company is unreliable, unworthy of trust) they might also demonstrate an indirect, or irrelevant, relationship. Consequently, a mediation effect of organization-based self-esteem between global self-esteem and negative affectivity is tested. Following the results, people tend to have different levels of global self-esteem. Those who believe in themselves and simultaneously act as if they have an emotional disinvestment in the organization seem more resistant to negative emotions complemented by uncertainty and lack of closure. Those with lower levels of self-esteem continue to identify with the organization in which they work; at the same time they tend to increase the level of negative affectivity, which is probably triggered by the organization’s negative feedback. These mechanisms might be partially responsible for the increasing incidence of work-related stress syndrome. The theoretical and practical implications are discussed in this chapter.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Negative Affectivity

- Organizational Commitment

- Organizational Identification

- Turnover Intention

- Temporary Contract

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

9.1 Introduction

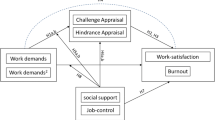

Burnout is a multifaceted syndrome associated with negative work characteristics and dysfunctional organization enduring over time. It acts mainly on workers following a development that has elements of invariance, but also a wide inter-individual variability. It has indirect effects on the users/customers of the organization and longer-term negative effects on the organization itself in terms of human and economic costs (e.g., Kivimäki et al. 2003; Mollart et al. 2011). In very simple terms, it can be defined as a condition in which there is a gap between what the workers feel they yield and what the organization and work itself return—not only as pay, but also as perceived social support, identification, and sense of well-being.

Traditionally (e.g., Shirom 2003; Schaufeli 2003; Maslach et al. 2001; Salyers and Bond 2001), it has been stated that burnout syndrome occurs with a feeling of emotional exhaustion (EE) accompanied by negative affectivity, a defensive reaction such as depersonalization (DP), and the emergence of a lack of involvement at work and low personal accomplishment (PA-). These events have negative implications for job performance (AbuAlRub 2004 ; Halbesleben and Bowler 2007; Moon and Hur 2011) and social relationships at the workplace (e.g., Boyas and Wind 2010). Individual factors might play the role of preconditioning on the emergence of burnout, usually triggered by significant environmental, social or organizational changes. This is the case of the contemporary worldwide economic crisis that has had a great impact on the western labor market since the summer of 2007. As a matter of fact, globalization, deregulation, increasing competition from developing countries, and temporary contracts turned out to be very common words in the workplace. At the same time managers in the later part of the last decade were compelled to make decisions on organizational interventions like reorganization, downsizing, and the fusion of companies (e.g., Cazes and Verick 2010).

Recently, it was shown that these interventions, although required, were perceived as threatening by the employees, creating among them a sense of insecurity, weakening their confidence in the company, and hence undermining the sense of identification with it and producing an increase in negative citizenship in the workplace (Iverson and Zatzick 2011; Klehe et al. 2011; Zhao et al. 2010). Moreover, in a recent multi-country study, László et al. (2010) suggested that job insecurity can be significantly associated with an increased risk of reduced physical and mental well-being in most of the countries involved (almost all situated in continental Europe). This result was compatible with those found by Chirumbolo and Areni (2010), Ferrie et al. (2005), D’Souza et al. (2003), Lau and Knardahl (2008), Rugulies et al. (2008), McDonough (2000), and Cheng et al. (2005) documenting the fairly large detrimental effects of job insecurity on health. Nonetheless, the effects of job insecurity on health seemed to be related to individual factors other than age, sex, marital and managerial status, work-related factors, and previous chronic diseases. In particular, László et al. (2010) supported the need to deeply evaluate the global self-esteem as a possible variable affecting the investigated association. Following Korman (1970), self-esteem is defined as the degree to which the individual “sees him [her] self as a competent, need-satisfying individual” (p. 32).

In line with the aforementioned issues, the introduction to this chapter portrayed the notion of self-esteem in terms of global—self-based—as well as organization-based dimensions. Afterwards, the contributions of organization to self-esteem as well as the role of organizational self-esteem as a mediation variable will be outlined. Finally, an empirical contribution will be presented and discussed.

9.2 Self-Esteem

After the seminal work of Korman (e.g., 1976) many research articles within the field of work and organizational psychology have focused on employee self-esteem (see Pierce and Gardner 2004 for a review). At the center of these works was the suggestion that an individual’s self-esteem, formed around work and organizational experiences, would play a significant role in determining employee motivation, work-related attitudes, and behaviors, i.e., job performance. Self-esteem is a global construct that seems quite appropriate for capturing some aspects of the personality greatly involved in work dynamics. In more general terms the concept of self-esteem refers to an individual’s overall self-evaluation of his/her competencies (Rosenberg 1965). Thus, individuals with high self-esteem have a “sense of personal adequacy and a sense of having achieved need satisfaction in the past” (Korman 1966, p. 479).

Another important contribution to the development of the construct of self-esteem in the workplace comes from pioneering research on social identity. At a theoretical level, Tajfel (1978) proposed three components that might contribute to one’s social identity: a cognitive component (a cognitive awareness of one’s membership in a social group—self-categorization), an evaluative component (a positive or negative value connotation attached to this group membership—group/organization-based self-esteem), and an emotional component (a sense of emotional involvement with the group’s affective commitment). Taken together these three components contribute to the explanation of most of the dynamics that characterize the complex Person/Organization relationship, the main ones being social identification (Mael and Ashforth 1992) and self-esteem (Rosenberg 1965, 1989). Later, Pierce et al. (1989) introduced the concept of organization-based self-esteem (similarly, Luhtanen and Crocker 1992, suggested the notion of collective self-esteem), which is defined as the degree to which an individual believes him/herself to be capable, significant, and worthy as an organizational member.

9.2.1 Social and Organizational Contributions to Self-Esteem

The abovementioned literature paid attention to the notion of self-esteem, essentially focusing on stable characteristics of the self. Nonetheless, the quality of the working experience seemed to play an important role in determining the level of this personality dimension. In line with this suggestion, the literature on the origins of global self-esteem (e.g., Brockner 1988; Franks and Marolla 1976) proposes that organization-based self-esteem is affected by several forces. These determinants can be categorized as:

-

1.

The implicit signals sent by the environmental structures to which one is exposed.

-

2.

Messages sent from significant others in one’s social environment.

-

3.

The individual’s feelings of efficacy and competence derived from his/her direct and personal experiences. A further major source from which self-esteem emerges are the social messages received and internalized that come from meaningful and significant others (Baumeister et al. 2003 for a review). In this sense an individual’s organization-based self-esteem is, in part, a social construction, shaped and molded according to the messages about the self transmitted by role models, teachers, mentors, and those who evaluate the individual’s work. Once these messages are internalized and integrated into the person’s conceptualization of the self, they become a part of the self-concept. Generally speaking, experiences of success in an organization will bolster an individual’s organization-based self-esteem, while the experience of failure will have the opposite effect. Bandura’s (1997) self-efficacy concept provides some insight into this relationship. He suggests that the impact of past performance (e.g., success and/or failure) on self-beliefs depends on the individual’s interpretation of that performance and the attributions that are made. Individuals who have successful experiences and who attribute that success to themselves are more likely to experience an increase in self-efficacy, which in turn and over time has an impact on organization-based self-esteem (Gardner and Pierce 1998, 2001; Pierce and Gardner 2009). Similarly, an individual who experiences failure and attributes it to the self will eventually experience a diminution of self-esteem.

9.2.2 Organization-Based Self-Esteem as a Mediating Factor

Several investigators have used organization-based self-esteem to provide insight into how or why certain bi-variate relationships unfold. In most cases organization-based self-esteem is found to mediate relationships between its hypothetical antecedents (such as level of pay, ways of organizing work, promotion of an organization’s socialization, leader–follower relationship) and consequences (such as job satisfaction and performance, work attitude, organizational commitment, citizenship in the workplace). It is the case of the empirical evidence shown by Abbott (2000), Lee (2003), Gardner et al. (2000), Riordan et al. (2001) and Aryee et al. (2003). Others have focused on the mediation role of organization-based self-esteem between the employees’ perception of their level of influence or of the organization support on organizational commitment as well as job performance. This evidence has been provided by Kostova et al. (1997) and Phillips (2000) respectively. In addition, Heck et al. (2005) investigated the mediating role of organization-based self-esteem of dispositional (i.e., negative affectivity), attitudinal (e.g., job satisfaction), relational (i.e., leader–member exchange), and behavioral (i.e., supervisory performance ratings) antecedents of workplace whining. They found support for the full mediational effects of organization-based self-esteem in each of the proposed relationships, with the exception of partial mediation in the case of performance. Wiesenfeld et al. (2000) provide additional insight into the explanatory role played by organization-based self-esteem in our understanding of the individual–organizational relationship. They hypothesized that organization-based self-esteem would mediate the relationship between perceptions of procedural fairness in the handling of layoffs in a downsizing context and the behaviors needed from managers in times of major organizational change. They found support for full mediation. Adding organizational-based self-esteem to the regression model eliminated the significant relationship between perceived fairness and managerial behaviors.

Finally, Pierce et al. (1993) found significant interaction effects between organization-based self-esteem and role ambiguity, conflicts, overload, work environment support, and supervisory support on achievement satisfaction. Jex and Elacqua (1999) also looked at the role condition–outcome relationship. They observed significant moderating effects of organization-based self-esteem in the relationship between role ambiguity and two stress outcomes: depression and physical strain symptoms. They also observed moderating effects in the relationship between role conflict and physical symptoms of stress, providing further support for behavioral plasticity. Gardner and Pierce (1998) focused their study on self-esteem and self-efficacy and their respective roles in influencing employee attitudes and behavior. They report observing full mediation effects for organization-based self-esteem in the relationship between generalized self-efficacy and both employee responses. In a more recent replication study, Gardner and Pierce (2001) found a positive relationship between organization-based self-esteem and generalized self-efficacy, satisfaction, commitment, and a negative relationship with intent to quit. Consistent with the study hypotheses, organization-based self-esteem emerged as the strongest self-concept in predicting most of the employee responses.

According to the abovementioned suggestions about the need to investigate in more detail the role of self-esteem in determining mental well-being (László et al. 2010), the aim of this presentation is to highlight the relationship between global (self-based) and organization-based self-esteem as a precursor of the level of negative affectivity in the workplace in an epoch characterized by a deep sense of job uncertainty and management decisions often directed at staff downsizing, ambiguities in the definition of work roles, and insecure job contracts.

9.3 Our Study

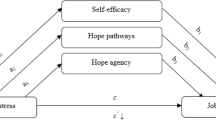

The principal aim of the present study was to investigate the role of global (self-based) self-esteem on the emergence of negative affectivity in times of job insecurity, controlling for organizational identification.

9.3.1 Hypotheses

Based upon and extending the empirical evidence taken into account in previous sub-sections of the chapter, the following hypotheses were formulated.

Hypothesis 1: Organization-Based Self-Esteem Predicts job Performance

We intend to confirm that organization-based self-esteem is essentially a job performance predictor. (e.g., Aryee et al. 2003; Van Dyne and Pierce 2003).

Hypothesis 2: Personality Characteristics Influence Affectivity in the Workplace

Specific personality characteristics, such as extraversion (Roesch and Wee 2006; Tosi et al. 2000), provide good bases for the development of positive feelings and behaviors (and against negative feelings, as well) toward the organization (e.g., Barrick and Mount 1991; Tett et al. 1991; Thoms et al. 1996; Barrick et al. 1998; Mohammed and Angell 2003; Van Vianen and De Dreu 2001; Tan and Tan 2008).

Hypothesis 3: Global Self-Esteem Predicts Organization-Based Self-Esteem in a Multi-Faceted way

Global self-efficacy is causally antecedent to organization-based self-esteem (Gardner and Pierce 1998). In the age of a relatively stable job market, global self-esteem has a direct effect on organizational-based self-esteem (e.g., Jex and Elacqua 1999; Tang and Ibrahim 1998; Van Dyne et al. 1990; Vecchio 2000; Borycki et al. 1998; Bowden 2002). Nonetheless, in times of work uncertainty employees (especially those characterized by high global self-esteem) might decrease their loyalty about organization and consequently their level of organizational-based self-esteem (Gossett 2002; Klehe et al. 2011, from a careers’ perspective).

Hypothesis 4: Organization-Based Self-Esteem Mediates Global Self-Esteem and Negative Affectivity

Employees tend to have different levels of global self-esteem. Those with lower levels tend to identify with the organization in which they work, but they tend to increase the level of negative affectivity, which is already quite high because of the low individual self-esteem and is amplified by negative feedback in the workplace.

9.3.2 Study Participants and Method

In our study participants were contacted between September 2008 and May 2009. There were 222 participants in the quasi-experimental study, white and blue collar workers employed in 23 micro and small companies in southeastern Italy who had experienced in the past few years managerial decisions (affecting employees) aimed at combating the effect of a financial crisis. The majority of participants were male (65%) and married (74%).

They were asked to fill in a structured questionnaire encompassing socio-demographic and work-related information, measures of personality (Big Five, Global Self-Esteem), measures of identification with the organization (including the size of Organizational-based Self-Esteem Manuti & Bosco 2012) and measures of negative affectivity. Information on job performance was also used as a control measure. The measurements used were: BFO (Caprara et al. 1994); RSES (Rosenberg 1965, 1989; Ellemers et al. 1999; Prezza et al. 1997); POMS (McNair et al. 1991; Van Rijsoort et al. 1999); QPA (Picucci 2009); OSI (Cooper et al. 2002).

9.3.3 Results and Discussion

-

1.

Organization-based self-esteem predicts

Our first hypothesis was that the Organizational Identification (OI) measures are predictive of job performance (in terms of job satisfaction). The higher correlation with job satisfaction was with Self Categorization (r = 0.39). OI explained approximately 17% of job satisfaction variance (F(3, 106) = 7.23; p < 0.001) with a larger, statistically significant, effect due to Self Categorization. Consequently, employees with a higher level of OI tended to show a higher level of job satisfaction.

-

2.

Personality characteristics influence affectivity in the workplace

Personality variables may act as protective factors against experiencing negative affectivity. A Single-Factor Principal Component Analysis (accounting for 62% of total variance) was performed and a combined measure of negative affectivity was obtained and used. In a subsequent multiple regression analysis, personality factors explained approximately 27% of variance of negative affectivity (F(3, 215) = 13.29; p < 0.001). This means that employees with lower Emotional Stability and lower Global Self-esteem showed significantly higher Negative Affectivity.

-

3.

Global self-esteem predicts organization-based self-esteem in a multi-faceted way

A multiple regression analysis confirmed the aforementioned prediction: personality explained 16% of variance of Organization-based Self-Esteem (F(6, 215) = 6.82; p < 0.001). The hypothesis of an inverse relationship, in times of job uncertainty, between different dimensions of self-esteem was confirmed. Nonetheless, it might deserve further investigation.

-

4.

Organization-based self-esteem mediates global self-esteem and negative affectivity

Affectivity and mood might be considered to be causes as well as effects in organizational research (e.g., Weiss and Cropanzano 1996; Fisher and Ashkanasy 2000). In our opinion, it is more likely that organization-based self-esteem is directly connected to the feeling of trust in the organization itself. If the organization fails to be viewed as reliable and trustworthy by the employees, those who persevere in showing a high level of organization-based self-esteem are probably more affected by general negative affectivity, in particular by feelings of anxiety, sadness, confusion, and anger. Nonetheless, negative affectivity was considered either as an outcome or a mediator in the two single-mediator-framework models performed (Baron and Kenny 1986; see also Collins et al. 1998; Shrout and Bolger 2002: Sobel 1982; MacKinnon et al., 2002, for both theoretical and practical power considerations, and Hayes 2009; Preacher and Hayes 2008 for the bootstrap procedure of indirect effects employed here). Organization-based self-esteem is more likely a mediator and negative affectivity an individual outcome (ab = −0.18; Zs = −3.04; p < 0.01; bootstrap 99% CI: -0.26/-0.11). This model seemed to be statistically robust in terms of parametric as well as nonparametric (bootstrap) analysis.

Global self-esteem has a protective effect on the emergence of negative affectivity, and organization-based self-esteem can concur with it, especially in times of relative stability of the labor market (Jex and Elacqua 1999; Tang and Ibrahim 1998; Van Dyne et al. 1990; Vecchio 2000; Borycki et al. 1998; Bowden 2002). Otherwise, in times of work uncertainty, the results of the present study seem to suggest an inverse relationship between global and organizational-based self-esteem in contrasting negative affectivity. In other words, lower levels of global self-esteem together with higher levels of organization-based self-esteem (despite an uncomfortable organization climate), tend to increase the level of negative affectivity.

Hence, lower levels of global self-esteem and more critical personal characteristics (such as low emotional stability and low resilience to stress) could lead to considering the organization as a source of well-being and confidence, even though the organization conveys ambiguous/unworthy messages.

This circumstance may generate the conditions for alienation and consequently the onset of negative affectivity and strain (e.g., Gossett 2002).

9.4 Conclusions

9.4.1 Loyalty of Employees, Levels of Identification with the Organization, and Organization-Based Self-Esteem

As argued by Knudsen (2003), taking inspiration from Simon’s Theory of Altruism, the promotion of organizational identification by inspiring organizational pride, loyalty, and values as encouraged by companies has a clear advantage in motivating the employees to actively pursue the targets of the organization. Pride, loyalty, and values associated with being a member of an organization are essential motivating factors for employees along with pay.

9.4.1.1 Organizational Policies

The present study agreed, in general terms, that the organizational policies focused on the loyalty of employees directly stimulate the increase in levels of identification with the organization, especially in the form of organization-based self-esteem.

9.4.1.2 Improvements

High levels of identification with the organization produce improvements in variables associated with work and the organization such as job attitude, job performance, and job satisfaction (e.g., van Dick et al. 2008).

Nonetheless, a different view on the relationship between organizational identification and job performance or loyalty to the organization is starting to emerge as the effect of temporary contracts and job insecurity (Gossett 2002; Klehe et al. 2011). Actually, feedback that employees receive from the organization in respect of their identification is important for their personal stability. Global self-esteem is a trimmer in the individual–organization’s circuit, probably together with other internal factors such as the need for closure: the need for certainty, intolerance of ambiguity, and preference for predictability (Chirumbolo and Areni 2010). As argued by Pierce and Gardner (2004) one attribute of individuals with low self-esteem individuals is that they look for and react to events in their environment, while those with high self-esteem are more confident in their personal qualities and consequently tackle and respond to environmental cues with a lower intensity. “Low self-esteem individuals experience more uncertainty as to the correctness of their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors and thus rely more on external cues to guide them. In addition, they seek acceptance and approval from others through conforming attitudinal and behavioral acts” (p. 596). It is likely that individuals with low self-esteem who avoid losing the acceptance and approval of management tend to increase their sense of identification with the organization. Because of adverse events, the organization is not able to provide stability to the individuals, who express their discomfort through negative feelings, affects, and mood.

9.4.1.3 Personal Resources

Alternatively, organizations could promote training to strengthen personal resources including self-esteem, self-efficacy, and assertiveness (e.g., Awa et al. 2010; Scarnera et al. 2009).

The enhancement of personal/work unrelated resources in the workplace might be much more useful for employees, especially in times characterized by poor employment stability. In our view, employees can generally understand that a crisis generates contraction of the workforce. However, they might find it more difficult to tolerate the organization asking them to be devoted and to identify with it, even in a climate of job uncertainty. Those suffering more from this circumstance in terms of negative affects and, probably, in terms of health risks, are employees characterized by a low sense of self-efficacy and self-esteem continuing to invest in the organization all their personal efforts.

9.4.2 The Promotion of a Supportive Work Environment

In order to mitigate the direct effect of negative affectivity on employees in the workplace as well as the indirect effects on the organization itself in terms of a probable departure from the corporate mission and an increase in human and economic costs (e.g., Kivimäki et al. 2003; Mollart et al. 2011), it might be appropriate for HR managements:

-

1.

To delay the promotion of the identification with the organization (e.g., Gossett 2002).

-

2.

To bring forward the strengthening of self-esteem, self-efficacy, and assertiveness of employees in order to stimulate their resilience as after a self-esteem threat (vanDellen et al. 2011 for a review).

-

3.

Offering them vocational training courses to be spent directly in anticipation of a future search for a new job (see Fig. 9.1).

At the same time, interventions aimed at improving the work–life balance (e.g., Sorensen et al. 2011) might be very useful given that they benefitted the individual in a broad sense rather than exclusively as a “worker.” These approaches, aimed at potentiating “persons” rather than “roles,” facilitate the realization of reciprocity between employee and organization. The enhancement of these resources could be targeted with a long-term reduction of negative emotions and mood, protecting the employees and the companies from their effects such as absenteeism due to sickness, sneaky turnover intention, and negative citizenship in the workplace (e.g., George & Jones 1996).

References

Abbott, J. B. (2000). An investigation of the relationship between job characteristics, job satisfaction, and team commitment as influenced by organization-based self-esteem within a team-based environment. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of North Texas, Denton.

AbuAlRub, R. F. (2004). Job stress, job performance, and social support among hospital nurses. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 36(1), 73–78.

Aryee, S., Budhwar, P., & Tan, H. H. (2003, August). Leader–member exchange and contextual performance: An examination of the mediating influence of organization-based self-esteem. A paper presented at the annual meeting of the Academy of Management, Seattle.

Awa, W. L., Plaumann, M., & Walter, U. (2010). Burnout prevention: A review of intervention programs. Patient Education and Counseling, 78, 184–190.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The Big Five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44, 1–26.

Barrick, M. R., Stewart, G. L., Neubert, M. J., & Mount, M. K. (1998). Relating member ability and personality to work-team processes and team effectiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 43–51.

Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I. I., & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4(Supplement 1), 1–44.

Borycki, C., Thorn, R. G., & LeMaster, J. (1998). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment: A comparison of United States and Mexico employees. International Journal of Commerce and Management, 8, 7–25.

Bowden, T. (2002). An investigation into psychological predictors of work family conflict and turnover intention in an organizational context (Working paper). Canterbury: University of Kent.

Boyas, J., & Wind, L. H. (2010). Employment-based social capital, job stress, and employee burnout: A public child welfare employee structural model. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(3), 380–388.

Brockner, J. (1988). Self-esteem at work: Theory, research, and practice. Lexington: Lexington Books.

Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., & Borgogni, L. (1994). Big five observer—Manuale. Firenze: Organizzazioni Speciali.

Cazes, S., & Verick, S. (2010). Labour market policies in times of crisis. In A. Watt & A. Botsch (Eds.) After the crisis: Toward a sustainable growth model (pp. 66–70). European Trade Union Institute. Bruxelles: European Trade Union Institute

Cheng, Y., Chen, C. W., Chen, C. J., & Chiang, T. L. (2005). Job insecurity and its association with health among employees in the Taiwanese general population. Social Science & Medicine, 61, 41–52.

Chirumbolo, A., & Areni, A. (2010). Job insecurity influence on job performance and mental health: Testing the moderating effect of the need for closure. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 31(2), 195–214.

Collins, L. M., Graham, J. W., & Flaherty, B. P. (1998). An alternative framework for defining mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 33, 295–312.

Cooper, C. L., Sloan, S. J., & Williams, S. (2002). Occupational stress indicator—Manuale. Firenze: Organizzazioni Speciali.

D’Souza, R. M., Strazdins, L., Lim, L. L., Broom, D. H., & Rodgers, B. (2003). Work and health in a contemporary society, demands, control, and insecurity. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 57, 849–854.

Ellemers, N., Spears, R., & Doosje, B. (1999). Social identity: Context, commitment, content. Oxford, England: Blackwell Science.

Ferrie, J. E., Shipley, M. J., Newman, K., Stansfeld, S. A., & Marmot, M. (2005). Self-reported job insecurity and health in the Whitehall II study: Potential explanations of the relationship. Social Science & Medicine, 60, 1593–1602.

Fisher, C. D., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2000). The emerging role of emotions in work life: An introduction. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21, 123–129.

Franks, D. D., & Marolla, J. (1976). Efficacious action and social approval as interacting dimensions of self-esteem: A tentative formulation through construct validation. Sociometry, 39, 4324–4341.

Gardner, D. G., & Pierce, J. L. (1998). Self-esteem and self-efficacy within the organizational context. Group and Organization Management, 23(1), 48–70.

Gardner, D. G., & Pierce, J. L. (2001). Self-esteem and self-efficacy within the organizational context: A replication. Journal of Management Systems, 13(4), 31–48.

Gardner, D. G., Pierce, J. L., Van Dyne, L., & Cummings, L. L. (2000). Relationships between pay level, employee stock ownership, self-esteem and performance. Australia and New Zealand Academy of Management Proceedings, Sydney, Australia.

George, J. M., & Jones, G. R. (1996). The experience of work and turnover intentions: Interactive effects of value attainment, Job satisfaction, and positive mood. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 318–325.

Gossett, L. M. (2002). Kept at arm’s length: Questioning the organizational desirability of member identification. Communication Monographs, 69(4), 385–404.

Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Bowler, W. M. (2007). Emotional exhaustion and job performance: The mediating role of motivation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 93–106.

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76, 408–420.

Heck, A. K., Bedeian, A. G., & Day, D. V. (2005). Mountains out of molehills? Tests of the mediating effects of self-esteem in predicting work place complaining. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35, 2262–2289.

Iverson, R. D., & Zatzick, C. D. (2011). The effects of downsizing on labor productivity: The value of showing consideration for employees’ morale and welfare in high-performance work systems. Human Resource Management, 50(1), 29–44.

Jex, S., & Elacqua, T. (1999). Self-esteem as a moderator: A comparison of global and organization-based measures. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 72(1), 71–81.

Kivimäki, M., Vahtera, J., Elovainio, M., Pentti, J., & Virtanen, M. (2003). Human costs of organizational downsizing: Comparing health trends between leavers and stayers. American Journal of Community Psychology, 32(1–2), 57–67.

Klehe, U., Zikic, J., Van Vianen, A. E. M., & De Pater, I. E. (2011). Career adaptability, turnover and loyalty during organizational downsizing. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(1), 217–229.

Knudsen, T. (2003). Simon’s selection theory: Why docility evolves to breed successful altruism. Journal of Economic Psychology, 24, 229–244.

Korman, A. K. (1966). Self-esteem variable in vocational choice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 50, 479–486.

Korman, A. K. (1970). Toward an hypothesis of work behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 54, 31–41.

Korman, A. K. (1976). Hypothesis of work behavior revisited and an extension. Academy of Management Review, 1, 50–63.

Kostova, T., Latham, M. E., Cummings, L. L., & Hollingworth, D. (1997). Organization-based self-esteem: Theoretical and empirical analyses of mediated and moderated effects on organizational commitment. Working paper, Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

László, K. D., Pikhart, H., Kopp, M. S., Bobak, M., Pajak, A., Malyutina, S., Salavecz, G., & Marmot, M. (2010). Job insecurity and health: A study of 16 European countries. Social Science & Medicine, 70, 867–874.

Lau, B., & Knardahl, S. (2008). Perceived job insecurity, job predictability, personality, and health. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 50, 172–181.

Lee, J. (2003). An analysis of organization-based self-esteem as a mediator of the relationship between its antecedents and consequences. The Korean Personnel Administration Journal, 27(2), 25–50.

Luhtanen, R., & Crocker, J. (1992). A collective self-esteem scale; self-evaluation of one’s social identity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18, 302–318.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 83–104.

Mael, F., & Ashforth, B. (1992). Alumni and their alma maters: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 103–123.

Manuti, A., & Bosco, A. (2012). Identificazione organizzativa: un contributo alla verifica delle proprietà psicometriche di due strumenti di misura/Organization identity: An account on psychometric properties of two measures. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422.

McDonough, P. (2000). Job insecurity and health. International Journal of Health Services, 30, 453–476.

McNair, D. M., Lorr, M., & Droppleman, L. F. (1991). Profile of mood state—Manuale. Firenze: Organizzazioni Speciali.

Mohammed, S., & Angell, L. C. (2003). Personality heterogeneity in teams: Which differences make a difference for team performance? Small Group Research, 34, 651–677.

Mollart, L., Skinner, V. M., Newing, C., & Foureur, M. (2011). Factors that may influence midwives work-related stress and burnout. Women and Birth. doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2011.08.002.

Moon, T. W., & Hur, W. (2011). Emotional intelligence, emotional exhaustion, and job performance. Social Behavior and Personality, 39(8), 1087–1096.

Phillips, G. M. (2000). Perceived organizational support: An extended model of the mediating and moderating effects of self-structures. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The University of Akron, Akron.

Picucci, L. (2009). Questionario delle Preoccupazioni Abituali/Everyday Worries Questionnaire. In L. Picucci & A. Bosco (Eds.), Il Testing Psicologico (pp. 53–61). Bari: Digilabs.

Pierce, J. L., & Gardner, D. G. (2004). Self-esteem within the work and organizational context: A review of the organization-based self-esteem literature. Journal of Management, 30(5), 591–622.

Pierce, J. L., & Gardner, D. G. (2009). Relationships of personality and job characteristics with organization-based self-esteem. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24(5), 392–409.

Pierce, J. L., Gardner, D. G., Cummings, L. L., & Dunham, R. B. (1989). Organization-based self-esteem: Construct definition measurement and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 622–648.

Pierce, J. L., Gardner, D. G., Dunham, R. B., & Cummings, L. L. (1993). The moderating effects of organization-based self-esteem on role condition-employee response relationships. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 271–288.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891.

Prezza, M., Trombaccia, F. R., & Armento, L. (1997). La scala dell’autostima di Rosenberg: Traduzione e validazione Italiana./The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Italian translation and validation. Bollettino di Psicologia Applicata, 223, 35–44.

Riordan, C. M., Weatherly, E. W., Vandenberg, R. J., & Self, R. M. (2001). The effects of pre-entry experiences and socialization tactics on newcomer attitudes and turnover. Journal of Managerial Issues, 13(2), 159–177.

Roesch, S. C., & Wee, C. (2006). Relations between the Big Five personality traits and dispositional coping in Korean Americans: Acculturation as a moderating factor. International Journal of Psychology, 41, 85–96.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rosenberg, M. (1989). Society and the adolescent self-image (Revth ed.). Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Rugulies, R., Aust, B., Burr, H., & Bültmann, U. (2008). Job insecurity, chances on the labour market and decline in self-rated health in a representative sample of the Danish workforce. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 62, 245–250.

Salyers, M. P., & Bond, G. R. (2001). An exploratory analysis of racial factors in staff burnout among assertive community treatment workers. Community Mental Health Journal, 37, 393–404.

Scarnera, P., Bosco, A., Soleti, E., & Lancioni, G. E. (2009). Preventing burnout in mental health workers at interpersonal level: An Italian pilot study. Community Mental Health Journal, 45, 222–227.

Schaufeli, W. B. (2003). Past performance and future perspectives of burnout research. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology, 29, 1–15.

Shirom, A. (2003). Job related burnout. In J. C. Quick & L. E. Tetrie (Eds.), Handbook of occupational health psychology (pp. 244–265). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445.

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In S. Leinhardt (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp. 290–312). Washington, DC: American Sociological Association.

Sorensen, G., Landsbergis, P., Hammer, L., Amick, B., Linnan, L., Yancey, A., Welch, L., Goetzel, R., Flannery, K., Pratt, C., & Workshop Working Group on Worksite Chronic Disease Prevention. (2011). Preventing chronic disease at the workplace: A workshop report and recommendations. American Journal of Public Health, 101(Suppl 1), S196–S207.

Tajfel, H. (1978). Social categorization, social identity and social comparison. In H. Tajfel (Ed.), Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 61–76). London: Academic.

Tan, H. H., & Tan, M. L. (2008). Organizational citizenship behavior and social loafing: The role of personality, motives, and contextual factors. Journal of Psychology, 142, 89–108.

Tang, T. L., & Ibrahim, A. H. S. (1998). Antecedents of organizational citizenship behavior revisited: Public personnel in the United States and in the middle east. Public Personnel Management, 27(4), 529–549.

Tett, R. P., Jackson, D. N., & Rothstein, M. (1991). Personality measures as predictors of job performance: A meta-analytic review. Personnel Psychology, 44, 703–742.

Thoms, P., Moore, K. S., & Scott, K. S. (1996). The relationship between self-efficacy for participating in self-managed work groups and the Big Five personality dimensions. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 17, 349–362.

Tosi, L. H., Mero, P. N., & Rizzo, R. J. (2000). Managing organizational behavior. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publisher Inc.

van Dick, R., van Knippenberg, D., Kerschreiter, R., Hertel, G., & Wieseke, J. (2008). Interactive effects of work group and organizational identification on job satisfaction and extra-role behavior. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72, 388–399.

Van Dyne, L., & Pierce, J. L. (2003). Psychological ownership: Feelings of possession and workplace attitudes and behavior (Working Paper). Eli Broad School of Management, Michigan State University.

Van Dyne, L., Earley, P. C., & Cummings, L. L. (1990). Diagnostic and impression management: Feedback seeking behavior as a function of self-esteem and self-efficacy. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Miami Beach, FL.

Van Rijsoort, S., Emmelkamp, P., & Vervaeke, G. (1999). Assessment the Penn State Worry questionnaire and the Worry Domains Questionnaire: Structure, reliability and validity. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 6(4), 297–307.

Van Vianen, A. E. M., & De Dreu, C. K. W. (2001). Personality in teams: Its relations to social cohesion, task cohesion, and team performance. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 10, 97–120.

vanDellen, M. R., Campbell, W. K., Hoyle, R. H., & Bradfield, E. K. (2011). Compensating, resisting, and breaking: A meta-analytic examination of reactions to self-esteem threat. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15, 51–74.

Vecchio, R. P. (2000). Negative emotion in the workplace: Employee jealousy and envy. International Journal of Stress Management, 7, 161–179.

Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 18, 1–74.

Wiesenfeld, B. M., Brockner, J., & Thibault, V. (2000). Procedural fairness, managers’ self-esteem, and managerial behaviors following a layoff. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 83, 1–32.

Zhao, J., Rust, K. G., McKinley, W., & Edwards, J. C. (2010). Downsizing, ideology and contracts: A Chinese perspective. Chinese Management Studies, 4(2), 119–140.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bosco, A., di Masi, M.N., Manuti, A. (2013). Burnout Internal Factors—Self-esteem and Negative Affectivity in the Workplace: The Mediation Role of Organizational Identification in Times of Job Uncertainty. In: Bährer-Kohler, S. (eds) Burnout for Experts. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4391-9_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4391-9_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN: 978-1-4614-4390-2

Online ISBN: 978-1-4614-4391-9

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)