Abstract

This chapter considers the relationships of student engagement with academic achievement, graduating from high school, and entering postsecondary schooling. Older and newer models of engagement are described and critiqued, and four common components are identified. Research on the relationship of each component with academic outcomes is reviewed. The main themes are that engagement is essential for learning, that engagement is multifaceted with behavioral and psychological components, that engagement and disengagement are developmental and occur over a period of years, and that student engagement can be modified through school policies and practices to improve the prognoses of students at risk. The chapter concludes with a 13-year longitudinal study that shows the relationships of academic achievement, behavioral and affective engagement, and dropping out of high school.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Student Engagement: What is it? Why does it matter?

This chapter considers the relationships of student engagement with academic achievement, graduating from high school, and entering postsecondary schooling. The concept of engagement has emerged as a way to understand—and improve—outcomes for students whose performance is marginal or poor. The idea that engagement behaviors can be manipulated to enhance educational performance promises significant payoff for students at risk of school failure.

In this chapter, early and more recent models of engagement are described together with the components of each model. Also, early and more recent research showing the relationship of these components to academic achievement and attainment is summarized. A first look at new longitudinal data on student engagement in grades 4 and 8, academic achievement, and high school graduation is described, showing the longitudinal nature of students’ school engagement and disengagement. The chapter concludes by summarizing the reasons to focus on engagement (and disengagement) when addressing problems of low achievement and dropping out. Different terms are used for engagement in this chapter; both student engagement and school engagement are used to connote students’ engagement in school.

Engagement and Risk

The recent emphasis on student engagement has evolved along with our understanding of what it means for students to be at risk. The ideas of risk and risk factors derive largely from medicine. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) defined health risk factors as “events, conditions, and behaviors in the life of any individual modify the probability of occurrence of death and disease for that individual when compared to others …in the [same] general population” (Breslow et al., 1985, p. I-1). As an illustration, risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) that cannot be altered—“conditions”—have been identified in epidemiological studies; these include variables such as gender, ethnicity, family history, and aging. Others risk factors are health outcomes at one point in time—“events”—but become precursors of CVD at later points in time, for example, obesity, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia.

The parallel to educational risk is clear. Research has identified a number of factors associated with educational failure and dropping out. Status risk factors (“conditions”) are sociodemographic characteristics that are difficult or impossible to alter through school-based interventions. Family socioeconomic status (SES), race/ethnicity, whether or not English is spoken in the home, family structure, and early pregnancy/parenthood are all highly related to academic outcomes. Educational risk factors (“events”) are educational outcomes at one age/grade that interfere with later academic achievement and educational attainment. Low grades and test performance in the early grades, in-grade retention, and student misbehavior are associated with more severe problems in later grades including school failure and dropping out (see Rumberger & Lim, 2008). Mild forms of school misbehavior in early grades can even escalate to acts of delinquency in later years (Broidy et al., 2003; Loeber & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1998). Dropping out is an educational risk factor—an outcome of earlier school experiences that becomes an obstacle to further schooling.

Like medical risk factors, status and educational risk factors cluster, that is, multiple factors tend to occur in the same individuals (Berenson, 1986; Finn, 1989). The correlations among status risk factors are well documented, and academic risk factors tend to cluster because academic problems in one grade make success in the following grades more difficult (Alexander, Entwisle, & Kabbani, 2001; Rumberger, 2001). For this reason, virtually every discussion of dropping out or delinquency refers to the interdependency with low academic performance, early behavior problems, and gender, race, and SES. The picture presented by status and academic risk factors gives educators little reason to expect that prognoses for at-risk students can be improved.

Research focusing on behavioral risk factors (the “behavior” component of the CDC definition) addresses the question “what do some students at risk due to status or educational risk factors feel and do to be academically successful?” The attitudes and behaviors that answer this question have been termed school engagement, that is, “the attention…investment, and effort students expend in the work of school” (Marks, 2000, p. 155). Engagement behaviors include the everyday tasks needed for learning, for example, attending school and classes, following teachers’ directions, completing in-class and out-of-class assignments, and holding positive attitudes about particular subject areas and about school in general. Because of its direct relationship with academic performance and inverse relationship with negative outcomes, school engagement has been viewed as a protective factor with respect to educational risk (Finn & Rock, 1997; Resnick et al., 1997; Steinberg & Avenevoli, 1998).

Disengaged students are those who do not participate actively in class and school activities, do not become cognitively involved in learning, do not fully develop or maintain a sense of school belonging, and/or exhibit inappropriate or counterproductive behavior. All of these risk behaviors reduce the likelihood of school success. Disengaged students may have entered school without adequate cognitive or social skills, find it difficult to learn basic engagement behaviors, and fail to develop positive attitudes that perpetuate their participation in class, or they may have entered school with marginal or positive habits that become attenuated due to unaddressed academic difficulties, dysfunctional interactions with teachers or administrators, or strong ties to other disengaged students. These students may begin what Rumberger (1987) has described as a gradual process of disengagement often leading to dropping out (see also Wehlage, Rutter, Smith, Lesko, & Fernandez, 1989).

Why Does Engagement Matter?

The engagement/disengagement perspective is helpful to educators searching for strategies to reduce the likelihood of school failure; for these reasons:

-

Engagement behaviors are easily understood by practitioners as being essential to learning. Further, the relationship between engagement behavior and academic performance is confirmed repeatedly by empirical research.

-

Engagement behaviors can be seen in parallel forms in early and later years. As a result, dropping out of school can be understood as an endpoint of a process of withdrawal that may have had its beginnings in the elementary or middle grades. Students at risk of school failure or dropping out can be identified earlier rather than later.

-

Remaining engaged—persistence—is itself an important outcome of schooling. Forms of persistence range from continuing to work on a difficult class problem to graduating from high school to entering and completing postsecondary studies.

-

Engagement behaviors are responsive to teachers’ and schools’ practices, allowing for the possibility of improving achievement and attainment for students experiencing difficulties along the way. (See section “Responsiveness to the school and classroom context” in this chapter).

Early and Newer Models of Engagement

Student engagement (and disengagement) was conceptualized in the 1980s as a way to understand and reduce student boredom, alienation, and dropping out. Educators argued that the school setting mediates student involvement and engagement which are, in turn, necessary for learning (Newmann, 1981; Newmann, Wehlage, & Lamborn, 1992; Wehlage et al., 1989). Engagement was defined as “the student’s psychological investment in and effort directed toward learning, understanding, or mastering the knowledge, skills, or crafts that academic work is intended to promote” (Newmann, 1992, p. 12).

One set of models emphasized the role of school context. Newmann (1981) argued that only major school reform could reduce student alienation and increase engagement. Six guiding principles were identified as promising: reforms that encourage voluntary choice on the part of students and student participation in policy decisions, maintain clear and consistent educational goals, keep school sizes small, encourage cooperative student–staff relationships, and provide an authentic curriculum. The need for school reform was echoed by Wehlage et al. (1989) who analyzed dropout prevention programs reputed to be effective, concluding that developing a strong sense of community with which students could identify is of paramount importance. As a result of the analysis, a “theory of dropout prevention” was forwarded that asserted: (a) social–cultural conditions and student problems and impediments affect two aspects of student behavior, educational engagement and school membership, and (b) these in turn affect students’ educational achievements.

Other models emphasize intrapersonal dynamics. A “self-system process model” was proposed based on the assumption that humans have basic needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness (Connell, 1990; Connell & Wellborn, 1991). Self-system processes, that is, appraisals of the self in relation to ongoing activity, are generated as a means to evaluate whether these basic needs are being met. If not, internal adjustments regarding the needs may be made. These processes are assumed to develop within an individual throughout the lifespan and to be affected by cultural context and interactions with others.

The action that results from self-system processes may take positive or negative forms, in particular, engagement or disaffection; these, in turn, are followed by the development of skills, social behavior, and adjustment (Connell & Wellborn, 1991; Skinner, Kindermann, Connell, & Wellborn, 2009). The self-system model asserts that schools that support competence, autonomy, and relatedness have higher levels of student engagement and academic success (Connell, Spencer, & Aber, 1994). Empirical studies have documented these relationships in diverse samples of elementary and secondary school children (Connell et al., 1994; Klem & Connell, 2004; Patrick, Skinner, & Connell, 1993).

Participation-Identification Model

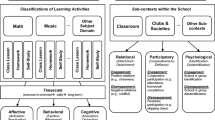

A third model had features of both the contextual and intrapersonal views. The participation-identification model (Finn, 1989) explained how behavior and affect interact to impact the likelihood of academic success. The behavioral component (participation) referred to the behaviors students engage in that involve them in the activities of the classroom and school. These include basic learning behaviors (e.g., paying attention to the teacher, responding to teacher’s questions, completing assignments), initiative-taking behaviors (e.g., engaging in help-seeking activities, doing more than the minimally required work, suggesting new ways to look at material being taught), and engaging in academic extracurricular activities. Participation also included the social tasks of school, for example, attending classes and school, following classroom rules, interacting positively and appropriate with teachers and peers, and not disrupting the class. The four types of behavior were originally combined under one umbrella (participation) but have been viewed as distinct in more recent work.

The affective component (identification) referred to students’ “feelings of being a significant member of the school community, having a sense of inclusion in school…” as well as the “recognition of school as both a social institution and a tool for facilitating personal development” (Voelkl, 1997, p. 296). The first of these has been referred to as “belonging,” “school membership,” “bonding,” “school connectedness,” and “attachment” by other researchers. The second was termed “valuing.”

The participation-identification model (Fig. 5.1) described a cycle that begins with early forms of student behavior (participation), leading over time to bonding with school (identification) and, in turn, to continued participation. The cycle has been described as follows.

Ideally, a child begins school as a willing participant. He or she is

…drawn to participate initially by encouragement from home and by classroom activities. Over time, participation continues as long as the individual has the minimal ability needed to perform required tasks and as long as instruction is clear and appropriate. There must be a reasonable probability that the student will experience some degree of academic success. As the student progresses through the grades and autonomy increases, participation and success may be experienced in a variety of ways, both within and outside the classroom. These experiences encourage a student’s sense of identification with school and continuing participation. (Finn, 1989, p. 129)

According to the model, behavior in the early grades is considered an important ingredient of school success. The classroom and school context need to be conducive to students’ developing a sense of school identification; positive rewards for achievement are especially important. Less-than-successful experiences are inevitable for all children, but the self-sustaining nature of the participation-identification cycle serves a protective function that enables students to navigate those situations.

On the negative side,

…Students lacking the necessary encouragement at home may arrive at school predisposed to nonparticipation and nonidentification. While exceptional teachers may engage the interest of some of these students, others may resist participation, becoming distracted, bored, or restless, avoiding the teachers’ attention or failing to respond appropriately to questions. In later years, minimal compliance or total noncompliance with course requirements may persist. Students may refuse to participate in class discussions, turn in assignments late, or arrive late or unprepared for class. As academic requirements become more demanding, this behavior can result in marginal or failing course grades. These students do not have the encouragement to continue participating provided by positive outcomes. If the pattern is allowed to continue, identification with school becomes increasingly unlikely. (Finn, 1989, p. 130)

This sequence of events can lead to disengagement and dropping out, but other avenues can also lead to these outcomes. Some students make reasoned decisions that time off (“stopping out”) work or family care is preferable at this point in life. Others may begin school as full participants but encounter obstacles (e.g., disciplinary measures) that cause them to withdraw. Nevertheless, “without a consistent pattern of participation and the reinforcement provided by success experiences, the emotional ingredient needed to maintain a student’s involvement or to overcome the occasional adversity is lacking” (p. 130).

The ideas of participation and identification were not as new to educators so much as the way they were assembled into a developmental cycle. The relationship between participation and academic achievement has been studied for decades. Attendance is a well-established factor in academic performance (deJung & Duckworth, 1986; Weitzman et al., 1985). Inattentive and disruptive behavior were identified by psychologist George Spivack and his colleagues as having strong correlations with achievement test scores among students in grades 1 through 6 (r’s from 0.15 to 0.74; Swift & Spivack, 1968) and in grades 7 through 12 (r’s from 0.26 to 0.32; Swift & Spivack, 1969). The study of “time on task” or “engaged time”—the period of time during which a student is actively engaged in a learning activity—produced a number of studies of the connections between classroom behavior and learning (Anderson, 1975; Berliner, 1990; Fisher et al., 1980). As an example, Anderson (1975) rated students in seventh through ninth grade as being “on task” or “off task” at regular time intervals and calculated the percentage of intervals that each student was on task. This measure yielded correlations between r = 0.59 and r = 0.66 with performance in particular math units. Follow-up studies also assessed the context, events, and instructional mode at each time interval in order to understand the factors that promote participation (Anderson & Scott, 1978).

Later research continued to find a strong relationship of participation with academic achievement. This comes as little surprise given the obvious importance of behavioral engagement for learning class material. One investigation correlated teacher reports of “effort,” “initiative-taking,” “negative behavior,” and “inattentive behavior” with achievement tests in over 1,000 fourth graders (Finn, Pannozzo, & Voelkl, 1995). Correlations with end-of-year achievement scores were all significant at p < .001 and in the expected directions; r’s ranged from 0.18 to 0.59.

Affective engagement has also been studied for some time. For example, sociologists hypothesized that identification with conventional institutions, including school and the workplace, serves to inhibit misbehavior (Hirschi, 1969; Kanungo, 1979; Liska & Reed, 1985). Affective engagement in this work was termed attachment, involvement, or bonding, and the obverse was termed social isolation or alienation. Research in school settings demonstrated that feelings of alienation are related to delinquency and dropping out and weakly related to academic performance (Elliott & Voss, 1974; Hindelang, 1973; Hirschi, 1969). In the Hirschi and Hindelang studies, large samples of middle- and high school students were administered questionnaires that included indicators of attachment/alienation and a measure of delinquent behavior called “recency.” In both studies, the percentage of high-attachment students who were low on recency was substantially greater than the percentage of low-attachment students who were low on recency (e.g., 68% compared to 33% and 64% compared to 34% for two attachment indicators in the Hirschi study). This was interpreted as showing that school attachment inhibits negative behavior.

In the Elliott and Voss (1974) study, over 2,600 high school students responded to questionnaires that yielded measures of normlessness and school isolation. The correlations of normlessness with delinquency ranged from r = 0.59 to r = 0.63 and with dropping out from r = 0.30 to r = 0.32; the correlations of school isolation with delinquency ranged from r = 0.27 to r = 0.34 and with dropping out from r = 0.20 to r = 0.26 (all significant at p < .01). More recent research indicates that affective engagement is related directly to student behavior and persistence and indirectly to academic achievement (see “Affective engagement” in this chapter).

Newer Models

Other models of engagement have been forwarded in recent years with three, four, or more components (e.g., Appleton, Christenson, Kim, & Reschly, 2006; Darr, Ferral, & Stephanou, 2008; Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004; Jimerson, Campos, & Greif, 2003; Libbey, 2004; Luckner, Englund, Coffey, & Nuno, 2006; Rumberger & Lim, 2008). Although different terminology makes comparison difficult, four dimensions appear repeatedly. Three correspond to the behavior component of the participation-identification model, and one corresponds to the affective component.

-

Academic engagement refers to behaviors related directly to the learning process, for example, attentiveness and completing assignments in class and at home or augmenting learning through academic extracurricular activities. Certain minimal “threshold” levels of academic engagement are essential for learning to occur.

-

Social engagement refers to the extent to which a student follows written and unwritten classroom rules of behavior, for example, coming to school and class on time, interacting appropriately with teachers and peers, and not exhibiting antisocial behaviors such as withdrawing from participation in learning activities or disrupting the work of other students. While a high degree of social engagement may facilitate greater learning, a low degree of social engagement usually interferes with learning, that is, it serves to moderate the connection between academic engagement and achievement.

-

Cognitive engagement is the expenditure of thoughtful energy needed to comprehend complex ideas in order to go beyond the minimal requirements.Footnote 1 Behaviors indicative of cognitive engagement include: asking questions for the clarification of concepts, persisting with difficult tasks, reading more than the material assigned, reviewing material learned previously, studying sources of information beyond those required, and using self-regulation and other cognitive strategies to guide learning. High levels of cognitive engagement facilitate students’ learning of complex material.

-

Affective engagement is a level of emotional response characterized by feelings of involvement in school as a place and a set of activities worth pursuing. Affective engagement provides the incentive for students to participate behaviorally and to persist in school endeavors. Affectively engaged students feel included in the school community and that school is a significant part of their own lives (belonging), and recognize that school provides tools for out-of-school accomplishments (valuing).

The components are summarized in Table 5.1. The first three indicate dynamism, or pull or, to use Marks’s (2000) term, “investment.” Affective engagement provides motivation for the investment of energy the others require. The four components may be exhibited by a student to different extents so it is difficult to label students as “engaged” or “disengaged.” But the components tend to be highly intercorrelated so that some students are highly engaged, and others disengaged, on multiple dimensions. This is likely to have a profound effect on their achievement and persistence.

There is a fine line between academic and cognitive engagement. Academic engagement refers to observable behaviors exhibited when a student participates in class work; this was called “participation” in the participation-identification model (Finn, 1989). Cognitive engagement is an internal investment of cognitive energy, roughly speaking, the thought processes needed to attain more than a minimal understanding of the course content.

Measurement Issues

The measures used to assess student engagement usually include indicators of engagement or disengagement in addition to questions that address the components directly (see Table 5.1). For example, a self-report instrument for assessing affective engagement might include questions about feelings of belonging (e.g., “I feel connected to my school”) plus other questions about relationships with teachers and classmates. An assessment of cognitive engagement might include students’ actual recall of the processes a student used to solve a problem plus other behaviors that suggest cognitive engagement (e.g., “Student uses a dictionary or the Internet on his/her own to seek information.” Student does more than just the assigned work). These two types of engagement—cognitive and affective—often require indirect measures because of the difficulty of assessing internal states directly (Appleton et al., 2006).

Table 5.1 is intended to define and delimit the components of engagement, but is not intended as an invitation to list every variable correlated with engagement. Some scales that purport to measure engagement include antecedents or consequences of engagement that lie outside the limits of the concept. We agree with Fredricks and colleagues (2004) that students’ perceptions of their own abilities, parental support, peer acceptance, teacher expectations, and other difficult-to-change contextual factors should be considered as antecedents. Academic accomplishments and graduating or dropping out are consequences. Even theory-based and well-thought-out scales obfuscate this distinction. One set of instruments includes items about students’ perceptions of their peers, mobility, retention in grade, parental support, academic performance, and drug and alcohol use, incorporating both antecedents and outcomes in their definition of engagement (Luckner et al., 2006). Others include questions about the fairness of school rules, the appropriateness of the tests given, parental support, feelings of safety in school, the extent to which school facilitates student autonomy, and the extent to which teachers like and support the student (Appleton et al., 2006; Darr, 2009; Luckner et al., 2006). These may all be antecedents of engagement, but none meets our criteria for engagement itself.

Clear definitions are also made difficult by attempts to sweep other terms under one umbrella. Liking for school, boredom, and anxiety are just that—liking for school, boredom, and anxiety (cf. Fredricks et al., 2004); no constructive purpose is served by calling them engagement. Yet some research and several reviews have included these and a plethora of other variables under the engagement umbrella (Jimerson et al., 2003; Libbey, 2004). The issue of definition needs further attention. Engagement models can be used to bolster student performance only to the extent that the components—and engagement itself—are well defined and easy for practitioners to understand.

Motivation and Engagement

The concepts of academic motivation and engagement appear to have much in common, sometimes leading to confusion. Indeed, the National Research Council book Engaging Schools (2004) used the terms simultaneously throughout (including a section title “Practices Enhancing Motivation and Engagement”) (p. 172), without discussing similarities or differences. Academic motivation, a form germane to educational performance, has been defined as “a general desire or disposition to succeed in academic work and in the more specific tasks of school” (Newmann et al., 1992, p. 13). Affective engagement—but not academic, social, or cognitive engagement—is also an internal state that provides the impetus to participate in certain academic behaviors. According to both motivational and engagement models, the actual behaviors are shaped by the context in which they occur.

Differences between the constructs are largely a matter of focus. Theories of motivation (e.g., Connell & Wellborn, 1991; Maslow, 1970; McClelland, 1985) attribute its source to inner drives to meet underlying psychological needs, for example, the needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness in the self-system model of Connell and Wellborn. Theories of engagement (e.g., Finn, 1989; Hirschi, 1969; Newmann, 1981; Voelkl, 1997) describe the development of affective engagement as starting with early behavior patterns and external motivators and gradually becoming internalized; the focus is on daily experiences and interactions with others.

Affective engagement is usually viewed more narrowly than is motivation or academic motivation. According to engagement models, it serves as a driving force for a specific set of school-related behaviors and interacts with those behaviors throughout the school years (Appleton et al., 2006; Finn, 1989, 1993; Fredricks et al., 2004; Furrer & Skinner, 2003; Newmann et al., 1992). The research summarized in this chapter shows that affective engagement is more highly related to behavioral forms of engagement than to academic achievement (see review that follows). Because of its connection with behaviors conducive to learning, it may be more for helpful for understanding and enhancing educational outcomes than the broader concept of motivation.

Responsiveness to the School and Classroom Context

According to the developmental models of engagement of Connell (1990) and Finn (1989), many factors impact school engagement including the school context and the attitudes and behaviors of peers, parents, teachers, and other significant adults. It is outside the purview of this chapter to review the antecedents of engagement. However, it is a basic tenet of the concept that it is responsive to the school and classroom practices. Research listed here has identified aspects of classroom environment (the quality of student-teacher relationships, instructional approaches) and the school environment (school size, safety, rules, and disciplinary practices) found to be important. Each is described in turn.

-

Substantial research has linked engagement to teacher warmth and supportiveness (Bergin & Bergin, 2009; Fredricks et al., 2004; Furrer & Skinner, 2003; Hughes, Luo, Kwok, & Lloyd, 2008; Marks, 2000; Skinner & Belmont, 1993; Voelkl, 1995). In this research, teacher warmth is a collection of attributes including liking and being interested in their students, believing in their capabilities, and listening to their points of view. Supportive teachers show respect for each student as an individual, hold clear and consistent expectations for student behavior, and provide academic assistance for students who need it, including those who have been absent for any reason.

-

Instructional approaches that require student-student interactions (e.g., cooperative learning), encourage discussion, or support the expression of students’ viewpoints (e.g., use of dialogue) have been found to facilitate student engagement (Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000; Johnson, Johnson, Buckman, & Richards, 1985; Osterman, 2000; Ryan & Patrick, 2001; Wang & Holcombe, 2010). Strategies that promote in-depth inquiry and metacognition have both been found to be related to increased student engagement. These include authentic instruction in which students use inquiry to construct meaning with value beyond the classroom (Newmann, 1992; Rotgans & Schmidt, 2011) and cognitive strategy use (Greene & Miller, 1996; Guthrie & Davis, 2003).

-

Organizational features of the school including school size are related to student engagement. Early studies of high school size found that smaller schools were associated with increased student participation, satisfaction and attendance, and social participation as a young adult (Lindsay, 1982, 1984). Since that time, a plethora of studies has confirmed the small school—high engagement connection (Cotton, 1996; Lee & Smith, 1993, 1995; National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2004). Research on small learning communities (SLCs) shows that small-school dynamics can be produced even when school buildings have large enrollments (US Department of Education, 2001). This work has found positive impacts of SLCs on various forms of student engagement (e.g., Darling-Hammond, Ancess, & Ort, 2002; Kemple & Snipes, 2000).

-

Perceptions of an unsafe environment and negative school sanctions can lead to student disengagement. Surveys have indicated that teachers in up to one fourth of American schools and students across the board perceived that rules were unclear, too severe, or enforced unevenly (AFT in American Educator, 2008; Voelkl & Willert, 2006; Wehlage & Rutter, 1986). Other studies have shown that student engagement was lower when students felt unsafe or victimized (Marks, 2000; Ripski & Gregory, 2009). Discipline policies perceived as too harsh are related to social forms of disengagement and dropping out (Hyman & Perone, 1998; McNeely, Nonnemaker, & Blum, 2002), while unfairness or apparent unfairness with which rules are enforced is related to behavioral and affective disengagement (Ma, 2003; Marks, 2000; Ripski & Gregory, 2009). Fair treatment by school staff has been described as fundamental to the development of identification with school (Newmann et al., 1992).

Several interventions to increase engagement have been tried and found to be effective. For example, First Things First (Connell & Klem, 2006) is a school-wide program that attempts to increase engagement at all grade levels by improving instruction and relationships between teachers and students. The Child Development Project (Battistich, Watson, Solomon, Schaps, & Solomon, 1991) attempts to create close-knit communities in classrooms and schools, thereby promoting several forms of student engagement. Both programs have been evaluated and shown to have positive results. (See Voelkl, 2012).

Engagement and Achievement/Attainment

Recent years have produced many studies of the relationships between engagement and educational outcomes. In this section, we summarize research conducted from the 1990s to the present in three categories: (1) Research showing the importance of engagement/disengagement to learning when both are observed simultaneously. This research demonstrates that behavioral risk is a major factor in producing academic risk. (2) Research that examined the relationship between engagement/disengagement in earlier grades and academic achievement and attainment in later years. This research shows that, without intervention, behavioral risk and academic risk grow in tandem through the grades. (3) Research showing that school engagement can overcome the obstacles presented by status and academic risk factors, that is, engagement can protect students from harm that may accrue.

The Importance of Engagement to Learning

Academic Engagement

Students across grade levels who exhibit academic engagement behaviors, such as paying attention, completing homework and coming to class prepared, and participating in academic curricular activities, achieve at higher levels than their less academically engaged peers. These behaviors are especially important for students who face obstacles due to status risk factors such as coming from a low-income home or having a first language other than English.

Studies of inattentiveness continue to find strong correlations between students’ achievement and their ability to ignore distractions, persevere on tasks, and act purposefully. A classic study of academic engagement (Rowe & Rowe, 1992) examined the attentiveness and achievement of over 5,000 children aged 5–14. Data were grouped by age (5–6, 7–8, 9–11, and 12–14 years old), but regardless of age group or other risk factors including SES and gender, significant negative correlations were found between lack of attention and reading achievement scores (r’s from −0.87 to −0.48). The effects were further shown to be reciprocal: path coefficients showed that inattentive behaviors in the classroom had strong, negative effects on reading achievement and low reading achievement scores led to increased inattentiveness. Reciprocal effects were also found in a longitudinal study of low-achieving first- through third-grade students (Hughes et al., 2008). These results offer partial support for the developmental cycle postulated by Finn (1989).

Some studies combined ratings of attentiveness with other forms of classroom engagement. Across all age groups, and regardless of the approach taken, substantial correlations are found with students’ academic performance. For example, in a study of 1,013 fourth graders (Finn et al., 1995), teachers rated the students on the Student Participation Questionnaire (SPQ) (see Appendix for complete questionnaire). The 28-item instrument questionnaire yields multi-item scale scores for “effort,” “initiative-taking,” “disruptive behavior,” and “inattentive behavior” (Finn, Folger, & Cox, 1991). The effort scale included items such as “student pays attention,” “student completes assigned seatwork,” and “student is persistent when confronted with difficult problems”; inattentive behavior included items such as “student is withdrawn/uncommunicative,” “student does not seem to know what is going on in class,” and “student loses, forgets, or misplaces materials.” Scale reliabilities ranged from 0.89 to 0.94.

In this study, the correlations of effort and initiative with achievement tests at the end of the school year, controlling for race, gender, and classrooms, ranged from r = 0.40 to r = 0.59; correlations of inattentive behavior with achievement ranged from r = −0.52 to r = −0.34. All correlations were significant at p < .001.Footnote 2 Further, students classified as high on inattentiveness had test scores that were substantially lower than those of nonproblematic and disruptive students.

Student- and teacher-reported engagement was correlated with classroom grades in a study of third- through sixth-grade students (grades averaged across subject areas) (Furrer & Skinner, 2003). The engagement measure included ratings of effort, attention, and persistence. While both correlations were significant, the correlation was higher for teacher reports of academic engagement (r = 0.57) than for student self-reported academic engagement (r = 0.33).

Engagement-achievement connections have been examined in the upper grades with some inconsistent findings. In a study of 586 ethnically and socioeconomically diverse tenth and 12th graders, students’ self-reports yielded a total score comprised of concentration (engagement) and interest and enjoyment (not engagement); the reliability of the total scale was α = 0.64 (Shernoff & Schmidt, 2008). The total was a significant but modest predictor of students’ GPAs for the entire sample (β = 0.11). When the data were disaggregated by race/ethnicity, the total was significantly but negatively related to GPAs among Black students (β = −0.42). No further analysis or explanation for the negative relationship was reported.

Two studies used data from nationwide samples of students, one based on eighth grade students who participated in the National Educational Longitudinal Study of 1988 (NELS:88) (Finn, 1993) and one based on tenth grade students who participated in the Educational Longitudinal Study of 2002 (ELS:2002) (Ripski & Gregory, 2009). In the latter study, a measure of behavioral engagement was constructed from teacher ratings of students on five behaviors from the Student Participation Questionnaire; the reliability of the scale was α =. 76. Significant positive correlations were found between engagement and reading and mathematics test scores (r = 0.36 and r = 0.39, respectively). The data were not disaggregated by race/ethnicity. These results were consistent with those from Finn, which reported strong positive relationships between engagement and achievement tests in reading, mathematics, history, and science for all students combined.

Homework

Academic engagement in the form of homework completion was examined in relationship to academic performance in two studies (Cooper, Jackson, Nye, & Lindsay, 2001; Cooper, Valentine, Nye, & Lindsay, 1999). The amount of homework completed had small but statistically significant correlations with teacher-assigned grades among elementary students in second and fourth grades (n = 214, r = 0.23) and among middle- and high school students (n = 424, r = 0.26). Other correlations were nonsignificant, including those between homework and standardized test scores in upper-grade students, and homework with attitudes toward homework (like/interest) and beliefs about homework (helps me learn) among elementary students. The effects of homework on academic achievement need further study to understand the types of homework that may be most useful and the impact of teachers’ grading or not grading homework.

Extracurricular Activities

In general, research on extracurricular activities has produced mixed results with respect to academic achievement (Feldman & Matjasko, 2005). However, when the nature of the activities is considered, a more consistent pattern emerges. Participation in academically oriented extracurricular activities, a form of academic engagement, is significantly related to academic achievement. In contrast, the relationship between athletics and achievement is generally nonsignificant, and correlations are significant but smaller when athletic and academic activities are combined.

Studies that focus on academic extracurricular activities are few and far between. A 7-year longitudinal study of 1,259 Michigan school children included measures of involvement in a limited set of academic activities, 4-year high school GPAs, and enrollment in a full-time college program (Eccles & Barber, 1999). Although the measures were limited, the regression coefficients for the two outcomes were small but statistically significant at p < .01 (β = 0.11 for GPA, β = 0.13 for full-time college), with statistical controls for gender, socioeconomic status, and student ability.

One of the most in-depth analyses used NELS:88 data for eighth- and tenth-grade girls (Chambers & Schreiber, 2004). In this study, in-school academic extracurricular activities (ISAO) were disaggregated from other forms. The all-girl sample may not have been a severe limitation because girls are significantly overrepresented in academic activities (Eccles & Barber, 1999). Participation in ISAO was the total number of academic activities, out of 16, in which a student participated. This was entered into multilevel regressions controlled for socioeconomic status and other forms of school activity. ISAO had significant positive impacts on academic achievement (p < .001) in all four subject areas at both grade levels when all students were considered together. When the data were disaggregated by race/ethnicity, the associations between ISAO and academic achievement were nonsignificant for African American and Latina eighth-grade girls. With only one exception, all relationships for tenth-grade girls were positive and significant regardless of race/ethnicity or subject. This study provided evidence that academic extracurricular activities have a weaker relationship with achievement in eighth grade than in tenth grade. In tenth grade, there is often a larger set of choices, and students tend to self-select either academic or nonacademic extracurricular activities.

When academic and nonacademic extracurricular activities were studied together, small-to-moderate but statistically significant correlations with academic achievement were found. For example, in a separate study using the eighth-grade data from NELS:88, all extracurricular activities considered together had weak but significant correlations with achievement in mathematics, reading, and science (Gerber, 1996). Again, race/ethnicity was an important factor: White students had higher correlations of extracurricular activities to achievement (r’s from 0.16 to 0.23) than did their African American peers (r’s from 0.07 to 0.13). Other research has produced similar results for students in grades 6 through 12 (Cooper et al., 1999) and for students in grades 10 and 12 (Marsh, 1992; Marsh & Kleitman, 2002). The latter also found significant small-to-moderate effects of high school extracurricular participation on university enrollment (r = 0.27) and months spent in a university (r = 0.30).

Qualitative and quantitative studies of the relationship of athletic activities with achievement and high school graduation (Booker, 2004; Chambers & Schreiber, 2004; Melnick & Sabo, 1992) have generally found nonsignificant associations for most students studied. However, some significant relationships were found in specific subgroups. For example, Melnick and Sabo used High School and Beyond (HS&B) to study the relationships of athletic participation with grades and graduation/dropping out among African American and Hispanic male and female students from three urbanicities. When significant interactions were discovered with urbanicity, 12 separate regressions were run for each dependent variable. Weak but significant relationships between athletic participation and grades were found among suburban African American males (β = 0.20) and rural Hispanic females (β = 0.10). Athletics and graduation were weakly but significantly associated among rural Black males (β = 0.23), rural Hispanic females (β = 0.17), and suburban Hispanic males (β = 0.14). From the small number and spottiness of the significant results, the authors concluded that “athletic participation has very little academic impact on minority youth” (p. 302). In contrast, Chambers and Schreiber’s (2004) study of eighth- and tenth-grade girls revealed a significant negative relationship between sports participation and reading achievement; racial ethnic groups were not disaggregated in this study. Despite the inconsistent findings, researchers have argued that sports may be one of the few remaining forms of engagement for students at risk of total disengagement (Finn, 1989; Pittman, 1991; Yin & Moore, 2004). This hypothesis is best tested through a closer look at individual students, perhaps in a qualitative study.

Social Engagement

The written and unwritten rules of behavior, when violated, often reduce academic performance. Most research on classroom social behavior is framed in the negative, that is, one or another form of misbehavior. In this section, we focus on attendance and common forms of indiscipline, for example, disrupting the class, failure to participate in class discussions, refusing to follow directions, disrespectful behavior, and fighting.

Attendance

It comes as little surprise that school attendance is highly related to academic achievement; time lost from exposure to teachers and teaching can only reduce the opportunity for learning. In a study of all Ohio public schools, Roby (2004) found strong significant correlations between attendance and achievement in grades 4, 6, 9, and 12 (r’s from 0.54 to 0.78). The 18 urban schools with the highest all-tests-passed rates on the Ohio test of Proficiency at fourth grade had higher average attendance (95.6%) than the attendance average at the 18 urban schools with the lowest pass rates (89.6%), a highly statistically significant difference. The author estimated that a school of 400 students with a 93% attendance rate, the average for Ohio, lost 25,200 h of student instructional time per year.

The association is also strong at the student level. For example, African American freshmen’s absenteeism was significantly and negatively correlated to GPAs (r = −0.64) in an urban high-risk high school (Steward, Steward, Blair, Hanik, & Hill, 2008). While noting that absences from school in general are negatively correlated to achievement, Gottfried (2009) differentiated between excused and unexcused absences in an investigation of second through fourth graders. The large-scale study of students in Philadelphia found that, as students trended toward more unexcused than excused absences, their grades on SAT 9 reading and math standardized tests declined. Students with 100% of their absences excused performed higher on the reading test than students with 100% unexcused absences regardless of the total number of absences. However, even excused absences began to negatively affect achievement when students reached 20 absences per year. While the author’s approach was informative, the children in the study were approximately 7–9 years old and, presumably, did not make their own decisions about attending school. The author speculated that high unexcused absences were indicative of negative family environments. The issue is sufficiently provocative that we believe the study should have delved into the actual reasons for these absences.

Classroom Social (and Antisocial) Behavior

Researchers have given little attention to the antecedents and consequences of “ordinary” classroom misbehaviors except for those attributable to child psychopathology. This is despite the facts that most students misbehave one time or another and that certain classroom and school conditions may actually promote misbehavior. Ordinary misbehavior (e.g., speaking out of turn, leaving one’s seat during class, refusing to follow directions, being late to class or school, talking back to the teacher, using an electronic device) interferes with teaching and learning and can potentially interrupt all students’ engagement in the classroom.

In a unique study of social engagement, sixth- and seventh-grade students were asked to nominate classmates who exhibited two prosocial behaviors (e.g., shares, cooperates) and three antisocial behaviors (e.g., breaks rules) (Wentzel, 1993). Two composite scores were obtained for each student by combining the ratings in such a way as to make them comparable; these were also validated by comparing them to teacher ratings of the same students. Correlation and regression analysis showed significant relationships of both scores with grades and standardized achievement tests (correlations from r = 0.35 to r = 0.55) even when gender, ethnicity, absenteeism, student IQ, family structure, and teacher preference for the students were included in the equations.

In the Finn et al. (1995) study of fourth graders (above), the disruptive scale was comprised of four items: the student “acts restless, is often unable to sit still,” “needs to be reprimanded,” “annoys or interferes with peers’ work,” and “talks with classmates too much.” The scale had correlations from r = −0.29 to r = −0.18 with norm-referenced and criterion-referenced achievement tests when race, gender, and teachers were controlled statistically; all were significant at p < .001. The decrement in achievement scores for students who were high on the disruptive behavior scale was statistically significant but not as large as the decrement due to being high on the inattentive scale. Antisocial behavior of eighth graders, defined similarly, was also found to be correlated significantly with mathematics and reading test scores, with and without statistical control for demographic characteristics (see “A study of behavioral and affective engagement in school and dropping out” in this chapter).

Cognitive Engagement

Studies of cognitive engagement and achievement have yielded mixed results, in part due to different methods of assessing internal processes. Direct assessments are accomplished by asking students to report the processes they use to learn course material, and indirect assessments use indicators that can be reported in paper-and-pencil form or observed by teachers. A direct approach was proposed by Benjamin Bloom: stimulated recall (Bloom & Broder, 1958) is a method through which events are recorded and then played back to students at a time shortly after the events occurred. During playback, the recordings are paused at critical moments, such as when a problem is posed or solved, and participants are asked to retell their thoughts or conscious actions. Stimulated recall was used later to gather data on cognitive engagement during reading and math lessons (Juliebo, Malicky, & Norman, 1998; Peterson, Swing, Stark, & Waas, 1984). To reduce bias due to the delay between the events and the time of recall, “think alouds” were developed in which verbal reports are given concurrently with the cognitive event (Afflerbach & Johnston, 1984). Think alouds, however, require cognitive effort that may detract from learning the material itself.

Indirect methods of assessment rely on observable indicators that a high level of cognitive engagement has occurred, for example, students’ initiative-taking, undertaking more difficult assignments, discussing class material with the teacher after school. The Student Participation Questionnaire (Finn et al., 1991) includes teacher ratings of student initiative-taking (e.g., “Student attempts to do his/her work thoroughly and well, rather than just trying to get by”) and cognitive tool use (e.g., “Student goes to dictionary, encyclopedia, or other reference on his/her own to seek information”). Self-report instruments include the Metacognitive Awareness of Reading Strategies Inventory (Mokhtari & Reichard, 2002) with items such as “I decide what to read closely and what to ignore” and “I take notes while reading to help me understand what I read.”

In a pivotal study of students’ cognitions, Peterson and colleagues (1984) used three approaches in collecting information on cognitive engagement of fifth-grade students: stimulated recall, videotapes of student behavior, and student questionnaires. In terms of on-task behavior, the researchers found that teacher observations were less highly correlated with student achievement (r = 0.10) than were stimulated recall measures (r’s from 0.21 to 0.33) or the attending subscale of the cognitive processing questionnaire (r = 0.48). The analysis of cognitive functioning led the authors to conclude that “students with higher levels of attention were not merely listening passively; rather, they were more actively processing the material than students with lower attention” (p. 504).

Studies of self-regulation and use of cognitive strategies in elementary and higher grades yield significant results for some measures and not for others. In a study of 42 kindergarten and second-grade students, teacher-rated failure to self-regulate was not associated with lower reading scores in kindergarten but became a significant influence (r’s from 0.37 to 0.51) on reading achievement in second grade (Howse, Lange, Farran, & Boyles, 2003). Data collection in the study also included teacher ratings of cognitive engagement indicators and a direct measure based on a computerized self-regulation task that required that the child continue to work at a job on one part of the screen while distracters were presented (SRTC-AV; Kuhl & Kraska, 1993). The SRTC-AV by itself did not correlate significantly with achievement scores for any group of students in the study.

Likewise, a combination of assessments was used to access cognitive engagement during reading by 492 ethnically diverse fourth graders (Wigfield et al., 2008). Included in this study were three measures that reflect cognitive engagement. First, teachers rated students on a short questionnaire that included three academic engagement questions and one about the use of cognitive strategies. Also, a question-writing task involved students reviewing information in a science packet and then writing as many “good questions” as possible on the topic. Questions were graded with a rubric that considered both number of questions generated and complexity of the questions written. Both variables had moderate-to-high significant correlations with scores on the Gates MacGinitie Test of Reading Comprehension: the teacher report (r = 0.57) and the question-writing task (r = 0.74).

In high school, English students’ use of deep cognitive strategies (e. g., putting ideas in one’s own words and self-regulation of what is and is not understood) was significantly correlated with classroom grades (r = 0.33) (Greene, Miller, Crowson, Duke, & Akey, 2004), as were seventh- and eighth-graders’ general strategy use in English (r = 0.14) (Wolters & Pintrich, 1998). Cognitive strategies were also correlated to math achievement (r = 0.11) and social studies (r = 0.22) When the middle school students reported the use of regulatory strategies such as planning and monitoring, significant and moderate correlations between self-regulation and achievement were found (r = 0.23 to r = 0.30). Self-regulation appeared to have a somewhat greater effect on achievement then does general strategy use.

Although we reviewed a limited number of studies, the use of self-regulation and cognitive strategies was correlated with academic achievement in all but the youngest (kindergarten) students. Both direct and indirect measures of cognitive engagement were notable in their relationships to achievement among students in fourth and higher grades. It is possible that measures of cognitive engagement cannot capture the nuances of cognitive functioning among very young students, or, as suggested by some psychologists, the skills involved in cognitive engagement have not yet crystallized in 5- or 6-year-olds.

Affective Engagement

Like cognitive engagement, affective engagement is often assessed through external indicators rather than the internal states they reflect. In the case of affect, this leads to a wide range of measures including some that seem remote from the definition of the construct. Unlike all other forms of engagement, however, the preponderance of research suggests that affective engagement is related indirectly to academic achievement (See Voelkl, 2012). It appears instead to affect other forms of engagement (academic, social, cognitive) which, in turn, affect learning (Osterman, 2000).

The relationships of feelings of belonging and valuing with academic achievement, motivation, and academic and social engagement in grades 6 through 8 were examined in studies by Goodenow (1993a, 1993b) and Voelkl (1997). In these studies, affective engagement was assessed through student self-report measures. Generally, small or inconsistent positive correlations were found with grades and standardized achievement tests. In the Voelkl study, identification with school was more strongly correlated with student participation than with achievement. A large-scale study of students in grades 7 through 12 used data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (ADD Health) (McNeely et al., 2002). The data included a measure of school connectedness together with a number of student and school characteristics. Although grade point average was significantly related to student connectedness, the strongest predictor of school connectedness of all individual characteristics was skipping school (behavioral engagement). In a mixed-method study of 61 African American high school students, Booker (2004, 2007) also found little to link a sense of belonging to achievement. Participants’ self-reports of school belonging on questionnaires counted for little or no variation in their achievement. This was corroborated by interviews. One student, when asked about the importance of sense of community in their school replied: “How is my achievement [related]? …don’t think it really matters about that [belongingness]…the majority of people here are cool” (Booker, 2004, p. 138). Ninety-two percent of all student comments echoed this sentiment.

On the other hand, affective engagement is associated with a range of psychological and behavioral outcomes (Maddox & Prinz, 2003; Osterman, 2000). Students who report high levels of belonging or identification with school also display higher levels of motivation and effort than do students who report lower levels of belonging or identification (Goodenow, 1993a, 1993b; Goodenow & Grady, 1993). The correlation of scores on Goodenow’s Psychological Sense of School Membership (PSSM) scale with expectations for school success in a sample of 301 urban junior high school students was r = 0.42 (p < .001) (Goodenow, 1993b). Differences in average PSSM scores among high-, medium-, and low-effort teacher ratings in a sample of 454 suburban middle-school students were statistically significant at the.001 level; effect sizes between adjacent groups were both approximately 0.5σ (estimated from results in the published report).

Low levels of belonging or identification are associated with negative behaviors including academic cheating (Voelkl & Frone, 2004), school misbehavior and discipline measures (Stewart, 2003), drug and alcohol use on school grounds (Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992; Voelkl & Frone, 2000), delinquent and antisocial behaviors (Maddox & Prinz, 2003), and high-risk health behaviors including suicidality, violence (Resnick et al., 1997), and dropping out of school (Jessor, Turbin, & Costa, 1998; Rumberger & Lim, 2008). A study of sixth- and seventh-grade students found that after controlling for family relations, effortful control, earlier conduct problems, and gender, school connectedness was negatively related to subsequent conduct problems (Loukas, Roalson, & Herrera, 2010). The interactions in the study also showed that connectedness offset the adversity presented by poor family relations or effortful control, that is, connectedness served as a protective factor.

Valuing

The belief that school provides the individual with useful outcomes may also be related to behavioral engagement and indirectly to learning, although the research base is rather sparse. The valuing component of affective engagement is distinct from general valuing of education. In an analysis of different meanings of valuing, Mickelson (1990) found that “concrete” school attitudes such as the belief that schooling pays off with good jobs were associated with positive school outcomes for Black students. More abstract attitudes were not, for example, the belief that “If everyone gets a good education, we can end poverty” (p. 51).

Concrete attitudes, or “utility,” are a prominent part of Eccles’s expectancy-value model of student decision-making (see Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). Research based on the model has demonstrated consistently that utility is related to students’ choices and behavior. The perceived utility of school and particular courses may be important in sustaining students’ participation in school—sometimes despite frustration and failure.

Student perceptions of the present and future value of literacy (reading and English) has an increasing, although still modest, effect on student achievement in the upper grades. In a study of over 5,000 students in 92 schools, perceived usefulness of reading had nonsignificant relationships with achievement among children 5–11 years of age (r’s from 0.00 to 0.09) but became a weak but significant factor among students from 12 to 14 years of age (r = 0.11) (Rowe & Rowe, 1992). Although not compared to prior years, sophomore, junior, and senior high school students’ perceptions of the value of English for future goals had higher correlations with course grades (r = 0.25 for all students combined) (Greene et al., 2004).

These findings are consistent with the participation-identification model (Finn, 1989), which proposes that identification with school (or disidentification) develops over time as a function of behavioral engagement accompanied by academic success (or failure) experiences. The model proposes further that the development of positive feelings of school belonging and valuing helps perpetuate productive behavioral engagement and academic performance.

Summary

Many studies of engagement bundle the components in various ways and some fail to provide information about the composition of their measures. Nevertheless, the picture is clear: the effects of behavioral engagement on educational accomplishments are consistently statistically significant and moderate to strong—no matter what student populations are studied, control variables taken into account or, for the most part, the composition of the measures. The effect of affective engagement on achievement is less consistent, but its relationships with behavioral engagement and high school graduation are consistently positive.

Engagement Predicts Later Achievement and Attainment

Studies of engagement show that early patterns of behavior affect students’ performance in later grades. Most of these studies used large-scale longitudinal data collected on urban populations, and assessed combinations of the four types of engagement.

Longitudinal studies have identified students who are at risk of dropping out for reasons other than status risk factors. The study with the longest duration was a 14-year longitudinal study of 790 Baltimore City school children that began in first grade (Alexander, Entwisle, & Horsey, 1997). Attendance and engagement behaviors (academic, prosocial, and antisocial behaviors) were assessed in first grade by examining school. As expected, early scholastic achievement and status risk factors were predictive of dropping out. In addition, students high on the engagement scale were significantly more likely to graduate than their less-engaged peers (odds ratio = 2.4). Attendance, more than tardiness or antisocial behaviors, was particularly important; first graders who missed 16 days of school were 30% less likely to graduate than students who missed 10 days or fewer. Alexander et al. concluded that habits of engagement formed at this early stage were shown to have enduring effects on student attainment.

The importance of attendance was underscored in other research that included attendance with measures of antisocial behavior, for example, studies of a large sample of sixth-grade students in Philadelphia (Balfanz, Herzog, & Iver, 2007) and eighth-grade students in Houston (Kaplan, Peck, & Kaplan, 1995). In the Philadelphia study, four warning flags of school problems in sixth grade were identified (absenteeism, suspensions for poor behavior, low math or reading scores). Of these, attendance rates of 80% or less were the most predictive of failure to graduate on time or in the following year.

A 9-year longitudinal study followed ethnically and socioeconomically diverse children from kindergarten through eighth grade (Ladd & Dinella, 2009). Students were identified as having either stable (high or low) or changing (increasing or decreasing) levels of engagement. Students who exhibited stable but poor combined engagement behaviors (e.g., school avoidance, not following rules, defiance) from first through third grade made less academic progress through eighth grade than did those who had stable but higher combined engagement. First graders with equivalent achievement had markedly different trajectories if they were increasingly behaviorally engaged, as opposed to those who decreased in behavioral engagement, ultimately resulting in lower grades on achievement tests for decreasingly engaged eighth graders. Thus, students with either high stable engagement or increasing engagement had higher levels of achievement in eighth grade than their less-engaged peers.

Beyond High School

Postsecondary outcomes have been found to be affected by engagement in elementary and high school. Using national longitudinal data (NELS:88) on students when they were in grades 8 through 12 and of college age, Finn (2006) examined three sets of predictors: demographic characteristics (status risk variables), high school achievement and attainment (academic risk variables), and measures of school engagement (behavioral risk variables). Four composites were formed for each participant in high school reflecting academic participation (extracurricular participation), social engagement (attendance, classroom behavior) and affective engagement (students’ perceptions of the usefulness of school subjects).

In regressions that controlled for status and academic risk factors, attendance and classroom behavior were significantly related to all three postsecondary variables studied: entering a postsecondary program, the number of credits earned, and completing a postsecondary program (odds ratios of 1.2–1.5). Participation in extracurricular activities was related to entering a postsecondary institution (odds ratio of 1.4), but not to credits earned or completion of program. The affective measure, perceived usefulness of school subjects, was not related to any postsecondary outcome. When employment and income were examined at age 26, the results were weak or nonsignificant. Only 2 out of 12 possible relationships were significant, those of high school attendance with current employment and classroom behavior with consistency of employment. For the most part, engagement in high school did not impact employment as a young adult.

Research done in Chicago schools corroborated these findings (Ou, Mersky, Reynolds, & Kohler, 2007) and extended the conclusions to adult criminal behavior by age 24. A troublemaking composite score (social engagement) in grades 3 through 6 was a significant predictor of incarceration and conviction (odds ratios of 1.4 and 1.5, respectively). Neither academic engagement nor attendance was significantly related to the income or measures of criminal behavior (conviction or incarceration).

Summary

The principle that continuing engagement throughout from the earliest grades onward is important to high school graduation and participation in postsecondary education. Academic and social engagement stand out as especially salient, although we could not locate any predictive studies of cognitive engagement and found only one recent study that included affective engagement

Engagement Mediates the Effects of Status and Academic Risk Factors

Resilient students are those who can overcome the barriers posed by status or academic risk factors to achieve acceptable outcomes. The study of resilience is important to help identify the factors that distinguish these individuals from their less successful peers in order to apply those principles to other students at risk. Research has shown that school engagement in the early, middle, and upper grades all contribute to student resilience.

Students who were considered at risk in grades 1 through 6 due to home factors (57% poverty, 42% single parent households, school in a high-crime neighborhood) participated in an evaluation of the Seattle Social Development Project (n = 643) (Hawkins, Guo, Hill, Battin-Pearson, & Abbott, 2001). The 18 participating schools were assigned to one of three conditions: full intervention in grades 1 through 6 designed specifically to increase student engagement, late intervention in grades 5 and 6 only, and a control (no intervention). Each year from age 13 to age 18, teachers rated students on academic, cognitive, and affective dimensions of engagement. At age 13 and every subsequent age, the groups showed substantial differences with the order full intervention group having the highest engagement and the control group the lowest. The groups diverged, and differences became larger still in the period from 16 to 18 years. Further, the engaged-at-18 students had higher GPAs, a lower history of arrests, fewer instances of dropping out, and less cigarette, alcohol, and drug use than did the other groups.

Several studies explored engagement and resilience during transitions from elementary to middle or junior high school. A study of 62 African American students from low-income homes noted a significant drop in GPAs between fifth (M = 2.25) and sixth grade (M = 2.05), but affective engagement was shown to protect against this drop (Gutman & Midgley, 2000). After controlling for psychological characteristics, home background, and prior achievement, a high sense of school belonging combined with high parental involvement was related to elevated sixth grade GPAs; the mean GPA in sixth grade for students with high affective engagement was approximately 3.2.

A second study examined the adverse effects of parent and teacher “role strains,” that is, pressure placed on adolescents by parents’ and teachers’ expectations (de Bruyn, 2005). In a Dutch study of 749 students just entering secondary school, role strain negatively impacted academic achievement (r = −0.19 to r = −0.36). A measure of academic engagement was shown to mediate these effects; students high on the scale had higher achievement despite the role strain they felt. In all, academic engagement increased the prediction of academic achievement from R 2 = 0.09 to R 2 = 0.36. Academic engagement and achievement in the study were highly correlated (r = .50). Both studies demonstrated the roles of home and school factors in bolstering student resilience across school transitions.

A nationwide American study was based on a high-risk sample of eighth graders who participated in the NELS:88 longitudinal survey. The sample comprised 1,803 African American and Hispanic students who attended public schools and lived in homes in the lower half of the SES distribution, based on a composite of parents’ education, parents’ occupations, and household income (Finn & Rock, 1997). Students were classified into three groups based on academic performance in eighth and tenth grade and dropout status in 12th grade: a small group of resilient completers (8.4%) with math and reading test scores at or above the 40th percentile for all students, self-reported GPA’s of “half B’s and half C’s” or better, and who would graduate with their class at the culmination of 12th grade; nonresilient completers who did not meet the achievement criteria but were still in school in 12th grade; and nonresilient dropouts who were reported as having left without graduating. Seven academic and social engagement measures were recorded for each student (three teacher-reported, four student-reported), plus sports and academic extracurricular activities.

Even when the analysis controlled for demographic factors, self-esteem, and locus of control, resilient completers were significantly higher than both groups of nonresilient students on five out of six measures of social and academic engagement, that is, lower rates of absenteeism, higher levels of classroom effort and homework, and fewer behavior problems. Differences were large, with effect sizes for the significant variables ranging from 0.47σ to 0.84σ. Only student self-reports of being prepared for class and participation in sports and academic curricular activities did not relate to student resilience.

A Study of Behavioral and Affective Engagement and Dropping Out

A partial version of this report was presented to the American Educational Research Association (Pannozzo, Finn, & Boyd-Zaharias, 2004). The authors are grateful to Gina Pannozzo for her excellent work and contributions to the execution of the study.

Little if any research has explored the development of engagement and its relationship to achievement over time, and even less has examined the connection between affective engagement and dropping out of school. This study, based on the participation-identification model (Finn, 1989), was designed to investigate dropping out as a developmental process related to students’ behavioral and affective engagement in grades 4 and 8. We used a unique data set in which achievement scores were recorded from kindergarten through eighth grade, engagement measures were obtained at several intervals, and high school graduation was later recorded. The three primary research questions were (1) Is behavioral engagement (academic and social) in grades 4 and 8 related to graduation/dropping out of high school above and beyond the effects of academic achievement during the same time period? (2) Is affective engagement in grade 8 related to graduation/dropping out? (3) Does affective engagement explain graduation/dropping out above and beyond the effects of behavioral engagement? The results presented here represent a first look at this database.

Procedures

Participants

Participants in this study were a subset of students who participated in Tennessee’s Project STAR, a longitudinal class-size reduction experiment. Students entered the study in kindergarten or first grade and were followed through high school. To be included in this study, they were required to have graduation/dropout information from high school transcripts or State Department of Education records and to have been rated on the grade-4 and/or grade-8 engagement instruments. The final sample of 2,728 students was similar to the full STAR sample of 11,600 students in all ways except the sample for this study had a higher percentage of White/Asian students (74.9% compared to 63.1%) and a higher percentage of students not eligible for free lunches (55.3% compared to 44.0%). Free lunch and race/ethnicity served as control variables in all analyses.

In each phase of the analysis, the sample included students who had key variables in grade 4 and/or grade 8. The fourth grade sample consisted of 1,421 students from 123 schools and the eighth-grade sample had 2,191 students from 119 schools. There were 753 students with both grade-4 and grade-8 data.

Measures

Achievement score composites in reading and math were derived for each student in grades K through 3 and in grades 6 through 8, respectively. Each composite was the first principal component of norm-referenced and criterion-referenced tests administered in the respective subject in spring of each school year.

Academic and social engagements were measured through teacher ratings of individual students on the Student Participation Questionnaire (SPQ; see Appendix) (Finn et al., 1991). Fourth-grade teachers completed a questionnaire in November for up to ten randomly chosen students in her class. Eighth-grade reading and mathematics teachers completed a shortened version of the questionnaire (14 of the same items), yielding two ratings of each student. For this study, two subscales were created from the SPQ, one that measured academic engagement as defined in Table 5.1 (e.g., paying attention, participating in class discussion, completing assignments) and one that measured social/antisocial engagement (e.g., needing to be reprimanded, acting restless, interfering with classmates’ work). In fourth grade, these scales had 16 and 7 items, respectively; scale reliabilities were α = 0.95 and α = 0.85. The eighth-grade scales had 6 and 5 items, respectively; scale reliabilities were α = 0.89 and α = 0.81.

Identification with school was assessed with the Identification with School Questionnaire (Voelkl, 1996) given to students in grade 8. The questionnaire is comprised of 16 items that assess students’ sense of belonging in and valuing of school. Belonging items include “I feel proud of being a part of this school” and “The only time I get attention in school is when I cause trouble.” Valuing of school includes items such as “School is one of the most important things in my life” and “I can get a good job even if my grades are bad.” Confirmatory factor analysis of the scale indicated that it is best scored as a single dimension (Voelkl, 2012). For this study, the reliability of the total scale was α = 0.84.

Analysis