Abstract

Settersten (Chap. 1) describes three hallmarks of young adulthood: the need to manage uncertainty, the need for fluid self-definitions, and the need for interdependence. We discuss the implications that rapidly developing technologies such as cell phones and social networking might have in these three areas. The Internet provides constant access to information but requires skills in use and evaluation that young adults may not have. Social media provide the possibility of niche-seeking, which could increase opportunities or stifle exploration. Cell phones and the Internet offer interdependence after leaving the family of origin, but may also hinder autonomy. Students use social networking to facilitate group behavior with real-world implications, as we show with an example of a student-constructed drinking holiday. Social technologies also have implications for family formation (e.g., meeting partners, establishing intimacy, and maintaining long-distance relationships). These technologies have the potential to widen or narrow the gap between individuals from different backgrounds. Finally, we suggest future research directions, including understanding whether (1) rapidly developing technologies lead to qualitatively new sociodevelopmental phenomena, or simply new forms of well-understood phenomena, (2) existing theories of development and family relationships can accommodate behaviors arising from new forms of social technology, and (3) technology brings with it new relationship forms, and what these forms might mean for development in young adulthood.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

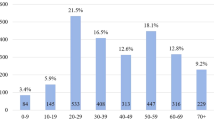

Computer and cell phone technology are ubiquitous for young adults. Among 18- to 24-year olds, 90% own computers, 94% use the Internet occasionally, and 79% had used the Internet the prior day. Ninety-four percent own cell phones, 86% send and/or receive text messages, and, among cell phone owners, make/receive a median of 10 calls and 50 texts per day (Pew Internet and American Life Project, 2010).

Statistics on social networking site usage are a moving target, changing dramatically in the past few years. Within its first year of being founded in 2004, Facebook reached nearly one million users. By 2008, Facebook had 100 million active users and the site reached 500 million active users in 2010 (Facebook, 2010). Even a few years ago, 94% of first-year college students spent some time in the prior week on social networking sites such as Facebook and MySpace, with 80% spending 1 or more hours per week, 51% spending 3 or more hours per week, and 9% spending 11 or more hours per week (Higher Education Research Institute, 2007). These college student usage rates are elevated compared to the general population of young adults, with reports that 72% of 18- to 29-year olds who use the Internet use social networking sites (Lenhart, Purcell, Smith, & Zickuhr, 2010).

Some have argued that technology increases disparities based on ethnicity/race or socioeconomic status (Hargittai, 2003; Matei & Ball-Rokeach, 2003), whereas others have argued that technology decreases the technology gap (Hampton, 2010). In general, usage rates suggest few differences by ethnicity/race, but larger differences by SES. For instance, cell phone ownership does not seem to favor European Americans. Across all age groups, African American and Latino Americans are more likely to own cell phones than European Americans and are more likely to access the Internet on their phones than European Americans (Smith, 2010). Across all age groups, there are no racial/ethnic differences in computer ownership, but there are differences by socioeconomic status, with college-educated individuals and individuals earning more than $50,000 per year more likely to own a laptop (Smith, 2010). Few differences in social networking site usage have been documented by race/ethnicity (Higher Education Research Institute, 2007).

These social technologies are relevant to all of the demographic changes described by Settersten in his chapter. For instance, they impact living independently because modern technology provides opportunities for inexpensive and frequent contact even when geographically distant. They impact the pursuit of higher education, as more young adults obtain degrees through online universities and more than 30% of college students take at least one course online (Allen & Seaman, 2010). They impact developmental transitions as young adults use the Internet to search for jobs and dating and marriage partners. In the remainder of this chapter, we discuss how new social technologies can both facilitate and/or hinder development in the three hallmarks of the young adult years that Settersten describes: managing uncertainty, fluid self-definitions, and interdependence.

Managing Uncertainty

Settersten cites increases in uncertainty for young adults of the current generation due to changing opportunities, less institutional support, and less clear life scripts. However, today’s young adults have access to more information than ever before. They may have less clear life scripts but they can usually find someone, somewhere on the Internet who describes a similar path to their interests. If they do not know something, they can Google it. For instance, recently (October 11, 2010) we entered “what can I do with” into Google’s search engine, and the automatic completion options were “my degree,” “an economics degree,” “a biology degree,” and “a psychology degree.” It’s telling that these are the automatic options. That question stem could easily be completed as: “What can I do with leftover hamburger meat” or “What can I do with my tax receipts?” Apparently, however, the most statistically probable inquiries concern what to do with university degrees. This instant access to information has tremendous advantages. Young adults can learn about different degrees and universities. They can search for information on how to write their resume, how to behave in the business world, how to prepare for an interview, or what to wear on interviews. At the same time, there is the possibility of information overload. The Google search “What can I do with a psychology degree” led to more than 7.5 million matches. Young adults need to learn how to evaluate this information for accuracy and intent. If they trust all sources equally, they could be receiving inaccurate health advice or applying to the universities that paid the most to come up in Google searches.

Recent research suggests that college students, although frequent consumers of online media, may not be particularly skilled in evaluating the quality of information or doing more than cursory work during searches. For instance, in one study students almost exclusively relied on Google for Web searches, rarely looked at search results beyond the first page, and generally trusted the search engine’s results. They tended to be very confident that they could distinguish accurate from inaccurate information. They also admitted to using Wikipedia frequently for coursework, even though they knew that instructors did not consider it a viable source of information. Therefore, they often used it without citing it in academic papers (Combes, 2008). Young adults and individuals with more education do appear to be more skilled consumers of online media than older individuals, in areas such as operating search engines, opening various file formats, and navigating Web sites. However, even young adults lack the ability to select and evaluate online information accurately and apply the search results to their goal (van Deursen & van Dijk, 2008). To better understand young adults’ ability to manage uncertainty, future research should identify the skills necessary to use the Internet and other media competently, how these skills might translate to other domains such as academic performance and career success, and how we can train adolescents and young adults in these areas. Such skills will help young adults manage the uncertainty of negotiating careers and life decisions.

Fluid Self-Definitions

Arnett (2000) referred to the period of development from age 18 to 25 as emerging adulthood and described it as a time of possibilities and identity exploration. Settersten notes the need during emerging adulthood to package oneself in multiple ways and for multiple settings. In this regard, there are in fact multiple outlets for possible selves when social interaction is mediated through Internet-based social networks. A young adult can package him/herself as a smart, studious worker-self on a LinkedIn profile targeted at potential employers, and as a fun, partying, witty self on a Facebook profile targeted at friends and acquaintances. Young adults can use social media to experiment with different personas in different outlets. However, the opportunity to fluidly explore possible selves also brings a risk of permanence. A young adult’s online presence can follow him/her. In fact, it is conceivable that it is harder to reinvent oneself in the current age of online permanency. A student in 1985 might have begun their first year of college with the sense of a fresh start. Assuming that few people from the student’s high school went to the same university, no one there would have known that student’s social standing in school, what clubs s/he had attended, or how often s/he had dated. In 2010, many college students are finding their roommates and other classmates online (through social networking sites such as Facebook) months before they begin college. Once they find each other, they have instant access to each others’ networks of friends, activities, and past. The ability to reinvent oneself is, therefore, somewhat double-edged. Although social media allow for experimentation with self-definitions and possible selves, it also leaves a legacy that may be difficult to overcome.

Fluidity also provides an opportunity for niche-seeking. Finding “like” others can provide social opportunities but also may prevent diversification. Historically, one of the best predictors of voluntary relationships has been physical proximity. Research prior to the Internet era suggested that both college freshmen and adults living in apartment buildings form friendships with those they live closest to within a building (Festinger, Schachter, & Back, 1950; Martin, 1974). Marital relationships demonstrate a similar proximity effect (Bossard, 1932). However, physical proximity may become less important when individuals can seek out similar others online. Why should a young adult become friends with the young woman in the next dorm room who is slightly different from her when she can use Facebook to find the other students at her university who overlap more closely in past experiences and immediate interests? Do young adults limit their chances for exploration and learning about other interests by finding individuals similar to themselves? The studies cited here regarding proximity and relationships are decades old, and it will be important to examine whether proximity continues to be a primary influence on friendship and relationship formation. Other future work could address whether young adults are forming a larger number of acquaintances at the expense of fewer, more intimate connections. In addition, future research can address the extent to which individuals transitioning to college seek out similarity or diversity in new platonic and romantic relationships.

Interdependence

Settersten describes a web of relationships with other adults and notes that these interdependent relationships can both provide a support network and foster individual development. Modern technology may facilitate this continued interdependence once young adults leave their family of origin’s home, city, state, or country. Many young adults now have access to frequent, easy, and inexpensive contact that can include inexpensive or free video conferencing from across the world. Recent data suggest that almost all first-year college students talked to their parents at least 1 out of 8 week days, and more than one third interacted daily (Hurtado et al., 2007; Small, Morgan, Abar, & Maggs, in press).

This access to interdependence has the potential to hinder autonomy and independent development in several ways. The term helicopter parents refers to parents who hover over their children even after they have moved out of their parents’ home (Lum, 2006; White, 2005). Although we know of no research to support claims about these parenting types, universities are beginning to create new positions, policies, and procedures to deal with or limit the influence of overly involved parents (Gabriel, 2010; Lum, 2006). As many as 70% of 4-year universities and colleges now have parent coordinators (Lum, 2006). It will be important for future research to examine the extent to which these behaviors are true phenomena or a media-created concept. If true, even if for a subpopulation of young adults, future research could examine the implications of overly involved parenting on young adults’ development of autonomy.

Some also have argued that new technology can lead to social isolation, and that the current generation may be more socially isolated as a result (Nie, 2001; Taylor & Keeter, 2010). Because individuals can accomplish almost everything necessary online, the need for face-to-face personal contact might seem to be sharply reduced. Limited research to date does not support this idea. In fact, online networks appear to extend and support rather than replace real-life friendships (Ellison, Steinfield, & Lampe, 2007; Haase, Wellman, Witte, & Hampton, 2002; Ito et al., 2008). The majority of young adults’ friends on social networking sites are also their friends in real life (Ellison et al. 2007; Ito et al., 2008).

Modern technology could potentially inhibit autonomy or create extended dependence on parents. That is, it is not clear the extent to which young adults are becoming independent if they call their parents multiple times per day for help with decision-making. Mortimer (Chap. 2) describes research which suggests that financial support from parents can erode self-efficacy. It is possible that intense and frequent emotional social support could erode self-efficacy, as well. Some social support from others is clearly beneficial, particularly at transitions (Kahn & Antonucci, 1980), but at a stage when developing autonomy is crucial, there may be such a thing as too much support. To examine how modern technology affects interdependence, researchers should examine how amount of contact and support relate both to the quality of the parent–offspring relationship, and more generally, to the young adult’s autonomy, competence, and self-efficacy. In addition, research should address how individual and contextual factors, such as offspring’s mental health, socioeconomic status, or romantic relationship status moderate these associations.

This juxtaposition – the need for autonomy and self-expression coupled with the need for interdependence – may be part of what makes social networking sites such as Facebook so popular with 18- to 24-year olds. For adults over 30, Facebook may be a way to stay in touch with others and keep up-to-date on life events. But for young adults, social networking sites may not only be about staying in touch, but also about being part of a larger group or community. In fact, our own recent research provides an example of the use of social networking Web sites for creating a larger group or sense of community, demonstrating that these new technologies can provide opportunities for risky or undesirable behavior.

In 2007, Saint Patrick’s Day occurred during spring break at a large state university with a dominant drinking culture. Frustrated that so many students would be out of town on the popular holiday, students quickly constructed and advertised a new party-based holiday, State Patty’s Day. As students described it in the largest Facebook group about State Patty’s Day: “We are encouraging a move from the weekend of the 17th to the weekend of the 2nd (the 2nd is a friday, b/c we all know how much fun it is to go to 9 a.m.’s three sheets to the wind). I know it doesn’t sound right, moving a holiday like St. Pats…but come on people, this is bordering on crisis! What would spring semester be without our weekend extravaganza that is St. Patrick’s Day?” To an outsider, this holiday may seem to be exclusively about getting drunk. However, to fully appreciate what motivated these college students, one must understand that beyond a shared interest in getting drunk, there was a shared sense of common social purpose.

We were uniquely positioned to study the effects of this spontaneous party because we were in the field doing daily Web-based surveys on alcohol-related behaviors (Lefkowitz, Patrick, Morgan, Bezemer & Vasilenko, in press). In this work, we searched for and recorded all Facebook posts that referred to State Patty’s Day in 2007, coding them for their content. We found that much of the social discussion did not simply focus on drinking or getting drunk, but also on the social aspects of drinking. For instance, many of their posts concerned the social context of drinking, as students discussed locations to converge to have communal drinking. A number of other posts focused on a sense of belonging to a larger community and of developing traditions. For instance, 17% of all posts concerned where/how to buy merchandise with State Patty’s Day logos so students could advertise their participation in the event. Finally, other posts referred to a sense of school pride and spirit. A frequent theme among these posts was the idea that the students were banding together to fight against the university, as some students even believed that the administration intentionally planned for St. Patrick’s Day to fall during spring break (Lefkowitz et al., in press).

We used 2 weeks of daily Web-based surveys on 227 students over 2,992 person-days to examine level of drinking by date, comparing student drinking on State Patty’s Day to other weekend (Thursday, Friday, or Saturday) days in a 2-month period that same semester. On State Patty’s Day, 51% of all students consumed alcohol, compared to 29% on other weekend days. Considering only students who drank on a specific day, students consumed an average of 8.23 drinks on State Patty’s Day, compared to 6.30 drinks on other weekend days (Lefkowitz et al., in press).

Police reports of criminal offenses during the same period corroborated the self-reported drinking behavior but at the community level. State Patty’s Day had more criminal offenses than any other day during the 2-month period (Lefkowitz et al., in press). Thus, based on both individual drinking outcomes and community-level crime outcomes, State Patty’s Day serves as a unique demonstration of the speed and efficacy with which motivated students can use social networking Web sites to create a large-scale event. Clearly, students’ networking goals, even if stemming from a longing for interdependence and need for a sense of belonging, are not always noble.

Students, and young adults more generally, may turn more and more often to social networking to spread and receive information about social events. This behavior is not limited to college students or even to the United States. Recent press attention highlights the use of Facebook in France to plan Apéros Géant, large drinking parties in public locations with as many as 10,000 attendees (Rosenberg, 2010). Thus, in many different contexts, young adults may use social networking to spread information about events involving risky and potentially harmful behaviors. However, this same sense of enthusiasm and desire to be part of a larger community also can lead to civic engagement and philanthropic acts. Cell phone users aged 18–29 are more likely than any other age group to make a charitable donation through text messaging (Smith, 2010). In early 2010, in response to an earthquake in Haiti, the Red Cross raised $32 million in less than a month through text messages (American Red Cross, 2010), and given higher rates of donating through texts for this age group, many of these donors were likely young adults.

Technology and Family Relationships

We have already described how new technologies such as the Internet and cell phones have potential for increased contact between young adults and their family of origin. From the parent perspective, a positive benefit might be increased opportunities for continued monitoring of their offspring’s activities, thoughts, and well-being without direct communication, by following their Facebook status updates and posted photos. Thus, parents can acquire knowledge of their offspring’s daily activities without being visibly intrusive.

Social technologies also have implications for family formation. Most notably, the Internet provides opportunities to meet partners through Web sites such as match.com. An online survey (which likely oversamples those who use the Internet frequently) reported that 1 in 5 individuals in committed relationships met their partner on a dating Web site. In the last 3 years, 1 in 6 married couples met each other on a dating Web site – more than twice as many who met at bars, clubs, or other social events combined (Chadwick Martin Bailey, 2010).

Second, social technologies have implications for establishing intimacy in burgeoning relationships. Individuals can learn about their new partners surreptitiously by reading about them and their friends on Facebook and in other social media. Many relationships may start with texting and instant messaging (Ito et al., 2008). It may be even easier to self-disclose intimate information in this less intimate context in the early stages of relationships. That is, some early flirting or information-sharing may occur in short snippets of information rather than in longer, face-to-face interactions. In fact, individuals who met online describe their relationships as committed; individuals who have never met in person tend to report more communication openness than committed partners who have met in person (Rabby, 2007).

Third, social technologies may assist in maintaining relationships in certain contexts, such as long-distance relationships or relationships in which one partner experiences extended travel. Telephone calls require both partners to be available simultaneously. Text messages and emails, however, allow one partner to share information or sentiments whether the partner can receive information at that time or not. This communication can serve both instrumental purposes (e.g., “my flight arrives at 7:00 p.m.”) and emotional purposes, such as sharing affectionate thoughts. Rhodes (2002) recommended that dual-career commuting couples stay in frequent contact and maintain rituals such as daily phone calls; current technology makes this frequent contact easier. Similarly, military families are able to stay in touch through email, instant messaging, and video messaging (Merolla, 2010).

Technology and Disparities

Modern technology has the potential to widen or narrow the gap between individuals from different socioeconomic backgrounds, though scholars present conflicting perspectives on which occurs (Hampton, 2010; Hargittai & Hinnant, 2008; Matei & Ball-Rokeach, 2003). Here, we focus on two areas where technology could affect the socioeconomic gap: social capital and social connectedness. With regard to social capital, some have argued that technology can help to close the gap for those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds because it provides equal access to information for all (Hampton, 2010). However, technology can only close the gap or decrease disparities to the point where young adults have access to the correct tools and the necessary skills to use them. We suspect that lack of tools and skills leads to increasing disparities for those from the lowest socioeconomic backgrounds. Individuals with less education have more trouble with a range of Internet-related tasks, including using search engines, identifying relevant information, and even opening browser windows (van Deursen & van Dijk, 2009). In addition, young adults who are more educated or come from more resource-rich backgrounds use the Internet for more capital-enhancing activities such as learning about news, health and financial information, and product information (Hargittai & Hinnant, 2008). The majority of 18- to 24-year olds own a cell phone, but 6% do not (Pew Internet and American Life Project, 2010). This 6% is less likely to have constant access to social contact with close others or instant access to information.

Technology provides opportunity for social connections throughout the day, while individuals work, study, etc. For college students or employees who are at their computers much of the day, no matter how busy they feel, they can make the choice to IM a friend, surf the Web, peruse Facebook status updates, or search for a new job. However, individuals who work construction, clean hotel rooms, or work as fast food cashiers may not have the same daily options to engage in these online social connections. Even if a young adult owns a cell phone and/or a computer, if his/her family of origin cannot afford them, the gap between social classes may widen.

Another domain of diversity that is particularly salient in young adulthood is in the area of sexual identity. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered (LGBT) youth may feel particularly marginalized and victimized during young adulthood as they grapple with their sexual identity and the coming-out process (Harper & Schneider, 2003; Rivers & D’Augelli, 2001). New technology has the potential to facilitate their exploration and social connectedness experiences (Elias, 2007; Ito et al., 2008). A young man grappling with his sexual identity living in rural Iowa can find other young men like him online. But this same technology can be used to harass or embarrass young adults, as shown in recent tragedies, including the death of Tyler Clementi at Rutgers University after his roommate taped his sexual encounter with another young man and broadcast it on the Internet (Foderaro, 2010). That is, technology may lead to opportunities for identification and social connectedness with others, but also for humiliation and shame on a large scale.

Future Directions

Past research has established the prevalence and frequency of use of various types of technology. Research needs to go beyond examining percentages or hours of use in activities, to understand the process of how technology is leading to changes in identity formation and social relationships. We know that time use, daily activities, and ways of contact are changing. What we do not yet know is whether the context of rapidly expanding technology is leading to more of the same. That is, are these newer forms of the same phenomena, with similar meanings for development? Or are technological changes leading to new phenomena, with new implications for development?

A number of theories explain normative development in the transition to adulthood, parent–offspring relationships at young adulthood, and romantic relationship formation and maintenance. Can existing theories explain the implications of using new forms of social technology, or do we need to adapt existing theories or even create new ones to explain these new phenomena? For instance, do our existing theories of identity development account for the kinds of exploration and experimentation that occur online? A line of research on identity development examines narratives or life stories to understand how individuals make meaning of their past experiences (McLean, 2005). Existing Web sites such as MySpace, Facebook, and Formspring may serve as rich resources for narratives and life stories that researchers may use to understand young adults’ naturally occurring self-narratives.

Another pressing question is whether theories of mate selection and family formation explain the process of evaluating, meeting, and becoming intimate with others online. Almost 40 years ago, Becker (1973) put forward the idea of a marriage market based in economic theory, in which each person attempts to find the best possible mate within the restrictions of marriage market conditions. Udry (1971) proposed the filter theory of mate selection, with the broadest filter for geographic propinquity. Individuals are most likely to date those who live nearby, and those who live nearby are likely to be similar to each other on other dimensions, such as SES and race/ethnicity, creating subsequent filters. However, the Internet expands the marriage marketplace exponentially and allows vastly increased access to others and flow of information. Economists might view such a market as more efficient, given that marriage consumers now have increased access to potential partners. Individuals also can essentially advertise themselves through online dating Web sites, deciding which attributes to highlight, downplay, and misrepresent. What does this new online market mean for existing theories of attraction and mate selection? Future research could examine the process of mate selection online versus in person, as well as the quality of romantic relationships formed online compared to relationships formed through traditional channels.

Symbolic interaction theory proposes that all interactions are reciprocal events between two or more individuals, conducted through symbols (Blumer, 1969). To what extent are these interactions or symbols the same or different when they occur outside of face-to-face interactions, such as through text messages or IMs? How do these interactions change when they become public, such as when someone changes their relationship status on Facebook or posts “I love you” on a partner’s Facebook wall? Future research could also address the ways that people manage relationships online versus by telephone or face-to-face, and the relative emotional experiences of these different ways of communicating.

Finally, it is possible that new technology brings with it new relationship forms. We do not yet know whether there are new relationship forms that current terminology and conceptualization fail to adequately address. There may be new categories of relationships because people who historically would not have interacted now can stay in contact as virtual friends. For instance, individuals who attended high school together but were not close friends can maintain contact through social networking sites. Individuals who meet through an interest group chat room or have blogs about related topics may never meet in person but can provide each other emotional support. It will be important to understand the role that such relationships play in individuals’ lives, partially in terms of social support and perceptions of networks. Just as the demographic changes that Settersten describes have led to new experiences, challenges, and developmental needs during young adulthood, current and future technological changes will likely lead to changes in the experience of being a young adult.

References

Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2010). Class differences: Online education in the United States, 2010. Retrieved from the Sloan Consortium website. http://sloanconsortium.org/publications/survey/pdf/class_differences.pdf .

Pew Internet and American Life Project (2010). Mobile access 2010 [Data file and code book]. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Mobile-Access-2010.aspx.

American Red Cross. (2010, February 11). Red Cross raises more than $32 million via mobile giving program. http://www.redcross.org/portal/site/en/menuitem.94aae335470e233f6cf911df43181aa0/?vgnextoid=43ffe0b8da8b6210VgnVCM10000089f0870aRCRD

Arnett, J. J. (2000). High hopes in a grim world: emerging adults’ views of their futures and of “Generation X”. Youth & Society, 31, 267–286.

Becker, G. S. (1973). A theory of marriage: Part I. The Journal of Political Economy, 81, 813–846.

Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bossard, J. H. S. (1932). Residential propinquity as a factor in marriage selection. The American Journal of Sociology, 38, 219–224.

Chadwick Martin Bailey. (2010). Recent trends: online dating. http://cp.match.com/cppp/media/CMB_Study.pdf.

Combes, B. (2008). The Net Generation: Tech-savvy or lost in virtual space? Paper presented at the IASL Conference: World Class Learning and Literacy through School Libraries.

Elias, M. (2007, February 7). Gay teens coming out earlier to peers and family. USA Today. http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2007-02-07-gay-teens-cover_x.htm?POE=click-refer.

Ellison, N., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook “friends”: exploring the relationship between college students’ use of online social networks and social capital. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12, 1143–1168.

Facebook. (2010). Company timeline. http://www.facebook.com/press/info.php?timeline.

Festinger, L., Schachter, S., & Back, K. W. (1950). Social pressures in informal groups: a study of human factors in housing. New York: Harper.

Foderaro, L. W. (2010, September 29). Private moment made public, then a fatal jump. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/30/nyregion/30suicide.html.

Gabriel, T. (2010, August 22). Students, welcome to college; parents, go home. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/23/education/23college.html.

Haase, A. Q., Wellman, B., Witte, J., & Hampton, K. (2002). Capitalizing on the Internet: social contact, civic engagement, and sense of community. In B. Wellman & C. Haythronthwaite (Eds.), The internet and everyday life (pp. 291–324). Oxford: Blackwell.

Hampton, K. N. (2010). Internet use and the concentration of disadvantage: globalization and the urban underclass. American Behavioral Scientist, 53, 1111–1132.

Hargittai, E. (2003). The digital divide and what to do about it. In D. C. Jones (Ed.), New economy handbook (pp. 822–841). San Diego: Academic.

Hargittai, E., & Hinnant, A. (2008). Digital inequality: differences in young adults’ use of the internet. Communication Research, 35, 602–621.

Harper, G. W., & Schneider, M. (2003). Oppression and discrimination among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered people and communities: a challenge for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31, 243–252.

Higher Education Research Institute. (2007, September). College freshmen and online social networking sites (HERI research brief). http://www.heri.ucla.edu/PDFs/pubs/briefs/brief-091107-SocialNetworking.pdf.

Hurtado, S., Sax, L. J., Saenz, V., Harper, C. E., Oseguera, L., Curley, J, Arellano, L. (2007). Findings from the 2005 administration of Your First College Year (YFCY): National aggregates. www.heri.ucla.edu/PDFs/2005_YFCY_REPORT_FINAL.pdf

Ito, M., Horst, H., Bittanti, M., Boyd, D., Herr-Stephenson, B., Lange, P. G., Robinson, L. (2008). Living and learning with new media: Summary of findings from the Digital Youth Project. John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Reports on Digital Media and Learning. http://digitalyouth.ischool.berkeley.edu/files/report/digitalyouth-WhitePaper.pdf.

Kahn, R. L., & Antonucci, T. C. (1980). Convoys over the life course: attachment, roles, and social support. In P. B. Baltes & O. G. Brim (Eds.), Life-span development and behavior (Vol. 3, pp. 253–286). New York: Academic.

Lefkowitz, E. S., Patrick, M., Morgan, N., Bezemer, D. H., & Vasilenko, S. A., (in press). State Patty’s Day: College student drinking and local crime increased on a student-constructed holiday. Journal of Adolescent Research.

Lenhart, A., Purcell, K., Smith, A., & Zickuhr, K. (2010). Social media & mobile internet use among teens and young adults. Pew Internet & American Life Project. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Social-Media-and-Young-Adults.aspx.

Lum, L. (2006). Handling “helicopter parents”. Diverse: Issues in Higher Education, 23, 40–42.

Martin, R. D. (1974). Friendship choices and residence hall proximity among freshmen and upper year students. Psychological Reports, 34, 118.

Matei, S., & Ball-Rokeach, S. (2003). The Internet in the communication infrastructure of urban residential communities: macro- or mesolinkage? Journal of Communication, 53, 642–657.

McLean, K. C. (2005). Late adolescent identity development: narrative meaning-making and memory telling. Developmental Psychology, 41, 683–691.

Merolla, A. J. (2010). Relational maintenance during military deployment: perspectives of wives of deployed US soldiers. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 1, 4–26.

Nie, N. H. (2001). Sociability, interpersonal relations, and the Internet: reconciling conflicting findings. American Behavioral Scientist, 45, 420–435.

Rabby, M. K. (2007). Relational maintenance and the influence of commitment in online and offline relationships. Communication Studies, 58, 315–337.

Rhodes, A. R. (2002). Long-distance relationships in dual career commuter couples: a review of counseling issues. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 10, 398–404.

Rivers, I., & D’Augelli, A. R. (2001). The victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. In A. R. D’Augelli & C. J. Patterson (Eds.), Lesbian, gay and bisexual identities and youth: psychological perspectives (pp. 199–223). New York: Oxford.

Rosenberg, G. (2010, June 1). France cracks down on pop-up drinking parties. Time. http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1992982,00.html.

Small, M., Morgan, N., Abar, C., & Maggs, J. (in press). Protective effects of parent-college student communication during the first semester of college. Journal of American College Health.

Smith, A. (2010, July 7). Mobile access 2010. http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Mobile-Access-2010.aspx. Accessed 10 Nov 2010.

Taylor, P., & Keeter, S. (2010). Millennials: a portrait of generation next: Confident, connected, open to change. Pew Research Center. http://pewresearch.org/pubs/1501/millennials_new_survey_generational_personality_upbeat_opennew_ideas_technology_bound.

Udry, J. R. (1971). The social context of marriage (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott.

van Deursen, A., & van Dijk, J. (2008, May). Measuring digital skills. Performance tests of operational, formal, information and strategic internet skills among the Dutch population. Paper presented at the ICA Conference, Montreal, Canada. http://www.allacademic.com//meta/p_mla_apa_research_citation/2/3/1/0/2/pages231022/p231022-1.php.

van Deursen, A. J. A. M., & van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2009). Using the internet: Skill related problems in users’ online behavior. Interacting with Computers, 21, 393–402.

White, W. S. (2005, Dec 16). Students, parents, colleges: drawing the lines. The Chronicle of Higher Education, p. B16.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Lefkowitz, E.S., Vukman, S.N., Loken, E. (2012). Young Adults in a Wireless World. In: Booth, A., Brown, S., Landale, N., Manning, W., McHale, S. (eds) Early Adulthood in a Family Context. National Symposium on Family Issues, vol 2. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-1436-0_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-1436-0_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4614-1435-3

Online ISBN: 978-1-4614-1436-0

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)