Abstract

We describe and discuss discursive approaches emerging over the last 50 years that in one way or another have contributed to identity studies. Approaching identities as constructed in and through discourse, we start by differentiating between two competing views of construction: one that moves progressively from existing “capital-D” social discourses to the domain of identity and sense of self and the other working its way up from “small-d” discursive practices to identities and sense of self as emerging in interaction. We take this tension as our point of departure for a discussion of different theoretical and analytical lenses, focusing on how they have emerged as productive tools for theorizing the construction of identity and for doing empirical work. Three dimensions of identity construction are distinguished and highlighted as dilemmatic but deserving prominence in the discursive construction of identity: (a) the navigation of agency in terms of a person-to-world versus a world-to-person directionality; (b) the differentiation between self and other as a way to navigate between uniqueness and a communal sense of belonging and being the same as others; and (c) the navigation of sameness and change across one’s biography or parts thereof. The navigation of these three identity dilemmas is exemplified in the analysis of a stretch of conversational data, in which we bring together different analytic lenses (such as narrative, performative, conversation analytic, and positioning analysis), before concluding this chapter with a brief discussion of some of the merits and potential shortcomings of discursive approaches to identity construction.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Examining the construction of identity from a discursive point of departure requires two lenses, the lens of discourse and the lens of construction, and bringing them to focus on identity. As a result of this fusion, certain aspects of identity theory and identity research gain center stage, whereas others are set aside. Having our own roots in two disciplinary orientations, language studies and psychology, we decided to approach this task by starting with a thorough overview on the topic of discourse, the way discourse theory and discourse analysis have developed in the field of language studies and emerged as new domains for theory and research over the last 60 years. Alongside this discussion, we will provide a sharper understanding of how construction is deeply embedded in discourse and how and why discourse becomes relevant for what are called identity practices. The constructionist framework that we draw on (see De Fina, Schiffrin, & Bamberg, 2006) is grounded in theory that suggests that phenomena typically considered as internal (e.g., knowledge, intentions, agency, emotions, identity) or external (varying widely from more obvious constructions such as marriage, money, and society to less obvious ones such as location, event, and continuity) have their reality in an intersubjectively reached agreement that is historically and culturally negotiated. These agreements are never fixed but subject to constant renegotiation—in which the forms of discourse that negotiators rely on play a major role.

It is important to note at the very start of our chapter that viewing identity as constructed implies a reorientation when it comes to identity research. Instead of following a more traditional essentialist project and asking what identity is—and from there attempting to pursue the lead into human actions that follow from how we defined identity—we suggest to study identity as constructed in discourse, as negotiated among speaking subjects in social contexts, and as emerging in the form of subjectivity and a sense of self. Our suggestion implies a shift away from viewing the person as self-contained, having identity, and generating his/her individuality and character as a personal identity project toward focusing instead on the processes in which identity is done or made—as constructed in discursive activities. This process of active engagement in the construction of identity, as we will show, takes place and is continuously practiced in everyday, mundane situations, where it is open to be observed and studied.

Furthermore, this process is best conceptualized as the navigation or management of a space between different dilemmatic positions. The three most pressing dilemmas revolve around (i) agency and control, resulting in the question whether it is the person, the I-as-subject, who constructs the way the world is or whether the me-as-undergoer is constructed by the way the world is—and how this dilemma is navigated on a case-to-case basis; (ii) difference and sameness between me and others, posing the question how we can draw up a sense of self as differentiated and/or as integrated within self–other relations—and how in concrete contexts we navigate in between those two; and (iii) constancy and change, posing the question how we can claim to be the same in the face of constant change and how we can claim to have changed in the face of still being the same—and what degree of continuity and development are necessary to develop and maintain a sense of self as unitary.

A discursive and constructionist approach to identity views these questions as empirical questions. Speaking subjects are confronted with ambiguities and choices, and languages offer options for saying the same things differently and expressing ourselves in a variety of ways. Learning another language, a dialect, or a particular vernacular makes it possible to come across differently. Consider for instance the offer to learn to speak like a Wisconsin local (Johnson, 2010), or maybe better, coming across as a Chicago pro (McLean, 2010).1 Bates (2005) invites us to learn to “speak like a CEO” so we are able to find out about the “secrets for commanding attention and getting results.” To add another curiosity, September 17 is the official Talk-Like-a-Pirate-Day, and a number of programs are offered so that anyone interested can come across authentic. Now, one may object that being able to talk like a pirate or a CEO (with results!) is not the same as being one. Nevertheless, it will be this close proximity between discourse and identity that will be explored in this chapter—and we shall see that discourse is a lot more powerful than just sounding like a person who we would like to be.

Let us briefly foreshadow what we consider the central merit of a general discursive perspective for the exploration of identity. A discursive approach brings together language and other communicative means in text and context and allows us to theorize and operationalize how the forms and meanings therein provide access to what are commonly called identity categories 2—general membership categories such as age, gender, race, occupations, gangs, socio-economic status, ethnicity, class, nation-states, or regional territories, to name a few. In order to provide our view of how discursive perspectives contribute to a better understanding of the processes of identity formation, negotiation, and maintenance, we divide our chapter into three parts. Following this introductory section, we first discuss how different discourse theories have contributed to establishing the centrality of language use in the constitution of social life and, thus, are to be considered crucial for the creation and negotiation of identities. In the same section we also delineate a distinction between “capital-D” and “small-d” discourses that is important in order to understand different ways of approaching and analyzing identity in discourse. We review some disciplinary and interdisciplinary trends in discourse analysis that have contributed to our understanding of specific aspects of identity: the construction of sameness and difference, the creation of categories of belonging, and the building of continuity and change. In the next section of this chapter, we summarize and highlight the contributions of discursive approaches to the empirical dimensions of shifting identity constructions and their maintenance from situation to situation as well as across the lifespan. We highlight the role of discourse as the medium that offers choices for navigating the three identity dilemmas: agency/control, sameness/difference, and constancy/change—before we turn in the next section to an illustration. In this section we exemplify, using a stretch of discourse among five 15-year-olds, how identity and identity research might benefit from a perspective that starts with a focus on local identity construction within small-d discourses (i.e., concrete choices of language forms and language functions—within a particular text and context). The goal of this illustration is to demonstrate the value of discourse analysis in revealing how, in such everyday and seemingly mundane interactive situations (in vivo), macro-level identities are reproduced through recurrent practices and ideologies that constitute capital-D discourses.

Discourse and Identity

Discourse: A Preliminary Working Definition

The term discourse has its roots in the Latin prefix dis- (in between, back and forth) and the verb currere (to run). When transferred onto the domain of talk, the metaphor of running back and forth between two poles is applied in two senses: First is the image that the texture of a stretch of talk (the form and content of what is said by a person) consists of a running back and forth between the structural whole and its component parts. The parts relate to one another in sequence as cohesively tied together and form—in a bottom-up and sequential procedure—the meaningful whole of, for instance, a recipe, a route description, or a narrative. At the same time, the overarching whole—let’s say the account of what happened at a pie-eating contest that can be heard as a fantastic barforama or as a revenge plot3—lends meaning to the particular actions of the participants in terms of what membership categories the participants are portrayed as occupying. The same image evoked by the metaphor of running back and forth can be applied in a second sense to the communicative situation, such as a conversation around a campfire, a dinner table, a group meeting, or a one-on-one interview, in which at least two speakers “run” back and forth between one another by taking turns. Within this image, the orderliness of the sequential arrangements of talk in interaction is focalized and brought to the fore.

Accordingly, many analyses of discourse concentrate on the sequential aspects of what thematically or topically is held together and merging into a thematic whole, whether produced through speaking, writing, and signing or by use of multi-modal repertoires such as gesture, gaze, facial expressions, or overall body posture. Alternatively, discourse analysis can delve deeper into the sequential moves that are taking place in the turn-taking behaviors between speakers—again by focusing on the same kinds of bodily and linguistic means used to accomplish this. Finally, as we illustrate at the end of this chapter, both foci—the textual and the contextual/interactional—may be combined, showing how the form as well as the content of a text have been interactionally emergent (for a more detailed methodological account of narrative analysis, see Bamberg, in press b). Regardless of which discursive lens dominates, it is crucial to address how the process of constructing meaningful units takes place through human action in time and space. Thus, discourse analysis typically takes into account the circumstances (context) of what has been said, how it was said, and why it may have been said—contextually embedded at a particular point in time at a particular location. And although the unit of analysis is an extended stretch of talk, one that is said to be “larger than the sentence” (Harris, 1952; Stubbs, 1983),4 the analytic focus can reach from the location of a particular breath intake to prosodic features, from pronunciations of a vowel in different phonetic environments to the use of well or oh, or from shifts between different tense forms or pronouns all the way up to the design of plots or life stories.

However, it seems to be a long shot from the analysis of breath intakes and the pronunciation of particular vowels or consonants to the question of how a person forms an identity or a sense of who they are. In the following sections, we will outline the kinds of linkages that have been formed between talk and identity by use of three different lenses. We start by following up on two at first glance opposing views on discourse, one that views the person as constructed in and through existing discourses (which, following Gee, 1999, we call capital-D discourses), while in the other the person agentively constructs who they are by use of discourse (which, again following Gee, 1999, we term small-d discourse). These two conceptualizations of discourse differ in terms of agency and control5 and have led to different ways of doing discourse analysis. A second lens sheds light on the different traditions that have looked at and analyzed discursive means as they are deployed when human agents enter social relations and engage in bonds with others—but at the same time begin to differentiate themselves from one another with an orientation toward authenticity and uniqueness. These traditions typically have their roots in applied fields of language analysis and have impacted on identity theory in a number of ways. A third lens will focus on one specific form of discourse—narrative. Narrative, for many, has become a privileged form of discourse for identity analysis, because it is by way of narrative that people are said to be able to construct a sense of a continuous self—one that fuses past and future orientation together into one’s present identity.

Capital-D and Small-d Discourse: Constructing a Sense as Agent

Having laid out a working definition of what is meant by the term discourse, it should be noted that this term is typically embedded in different theories and applied to different fields of investigation and analysis.6 Capital-D discourse theoreticians such as Habermas, Foucault, and Lyotard agree on the relevance of discourse for the constitution of discursive practices that become the distinguishing features of different discourse communities. Within a capital-D discourse perspective, it is assumed that the dominant discursive practices circle around and form the kind of thought systems and ideologies that are necessary for the formation of a consensus that extends into what is taken to be agreed upon, what is held to be aesthetically and ethically of value, and what is often simply taken to be true. Discourse theoreticians have developed varying theories that mark discourse as central for the interface between society and individual actions. Some stress its role in laying the foundation for a universal “discourse ethics” (cf. Apel, 1988; Habermas, 1979, 1981). Others see it as providing the constitutive principles for the historical formation and the changes of thought systems (regimes of truth—Foucault, 1972). Still others conceive of discourse as providing the basis for differing thought systems that dissent among or even contradict one another (discourse genres—Lyotard, 1984).

Within these kinds of societal discourse theories, there is a tendency to see individual and institutional identities as highly constrained by societal norms and traditions. Thus, for example, within a Foucauldian approach, it is assumed that it is the engagement in discursive communal practices that forms speaking subjects—and their worlds (Foucault, 1972). Typically, in this theoretical framework, subjects are assumed to have some choice in making use of existing patterns that can be found in their culture, but they do not create the practices in which they engage. Rather, practices are imposed onto them by their culture, society, or communal norms. Thus, chosen identities stem from already existing repertoires (Foucault, 1988, p. 11) that can arguably be viewed as categories or domains.

Although theoreticians such as Foucault, Habermas, and Lyotard posit that discourse necessarily also consists of what is said—what is being talked about in terms of topics, themes, and content—and how culturally established repertoires are put to use, their attention has traditionally centered on the broader social and institutional conditions that make this possible. These conditions frame and, even more strongly, constrain who can say what is said, under what circumstances it can be said, and how it actually may have to be said so it will be communally validated. In other words, the analysis of discourse, especially along Foucauldian lines, focuses on the conditions that hold particular discourses together. Also, explored is how conditions have changed over time—such that over history we have come to shape and reshape our views of ourselves. The goal within these societal discourse theories is to investigate the general communal and institutional conditions under which discourses can become “regimes of truth,” that is, frames within which social life is talked about and understood and the impact of these frames on the local contexts of everyday in vivo and in situ interaction. Therefore, these theorists see identity as fundamentally determined by such societal macro-conditions. In order to understand alternative approaches to identity, it is therefore important to distinguish between these general societal contextual conditions (as framing and delineating local conditions) that can be characterized as capital-D contexts and the kinds of local in situ contexts within which subjects “find themselves speaking” that can be described as the small-d contexts of everyday activities.

In contrast to theories that explore capital-D discourses, discourse theorists who have been working in more linguistically informed traditions have tried to better understand and empirically investigate the relation between what is said, how exactly it is said, and the functions that such utterances serve in their local in vivo context. Harris (1952) has been credited as the first linguist to develop discourse analysis, even though his work preceded the study of sentence structure (syntax) and excluded anything but language (hence, no context). Harris worked at the level of morphemes (units of form and meaning including affixes and words) to find morphological patterns distinctive to different types of texts. It was his bottom-up work of identifying patterns of morphemes that accrued to create texts. More contemporary approaches (e.g., Smith, 2003) examine how syntactic patterns of sentence structures combine into particular types of texts and discourse genres (e.g., narratives, descriptions). In the footsteps of these structural approaches to text were widespread attempts to link analytically the semantic and syntactic patterning in language with how speakers intend to convey meaning in interaction (e.g., Brown & Yule, 1983; Coulthard, 1985/1985; Levinson, 1983; Schiffrin, 1982, 1985, 1994; Stubbs, 1983).

Similarly to the capital-D discourse tradition, linguistically informed small-d discourse theorists also start off from the assumption that the choices that speakers can make when engaging in talk (spoken, written, or signed) are limited. However, for representatives of the small-d perspective on discourse and discourse analysis, the actual choices made in the form of performed in vivo utterances constitute the center of interest and analysis, because they are taken to reveal aspects of how speakers make sense of the context within which they move and accordingly how they weave relevant aspects of this context into their utterances. In other words, speakers, in their choices of how they say what they say—which may be as detailed as a breath intake at a particular point in the interaction—are interpreted as making use of (indexical) devices that cue listeners on how to read their messages as interactively designed. It is through a reading of these means that hearers (or more generally, recipients) come to a reading of the speaker’s intentions and ultimately to a reading of how speakers present a sense of who they are.

Of course, the presentation of self in everyday interactions is a far cry from being transparent or easy to read (cf. Goffman, 1959). For example, a speaker may use certain lexical items, pronunciations, syntactic constructions, and speaking styles that index particular social membership categories such as those indicated at the outset of our chapter: age, gender, region, social class. The local contexts within which self-presentations are displayed (intentionally or unintentionally) are continually shifting, making it difficult to make attributions. These local contexts nevertheless form the ground on which situated meanings can be assembled and related to culturally based folk models of person, personality, and character. Thus, the in situ context within which the enunciation and interpretation of a sense of self are taking place is possibly best characterized as the small-d context that needs to be understood and analyzed when making sense of small-d discourse.

Also challenging for the attribution of identity, however, is a view of communication developed by H. P. Grice (see discussion in Schiffrin, 1994, Chapter 6). Grice points out that communication is based not only on language but on implicit cultural presuppositions of cooperation (or strategic violations thereof) that depend on language and context as resources through which a hearer recognizes a speaker’s intention. The problem here is that the linguistic patterns used by a speaker may not necessarily be recognized by the speaker and/or the hearer as indices to particular identity categories.

There have been attempts within the frame of social psychology, particularly in the United Kingdom, to bring together small-d and capital-D perspectives into a synthetic form of analysis that traces normative practices as impacting on identity formation processes, while simultaneously paying attention to the local conversational practices in which notions of self, agency, and difference are constituted and managed. Potter and Wetherell (1987) developed an approach to identity analysis that centers on the analysis of interpretive repertoires. Interpretive repertoires are defined as patterned, commonsensical ways that members of communities of practice use to characterize and evaluate actions and events (Potter & Wetherell, 1987, p. 187). In recent writings, Wetherell (2008) shifted the terminology slightly to psychosocial practices as the basic unit of analysis. “Psycho-discursive practices are recognizable, conventional, collective and social procedures through which character, self, identity, the psychological, the emotional, motives, intentions and beliefs are performed, formulated and constituted” (p. 79).

The connection between “on the ground” in situ and in vivo interactive practices and wider cultural sense-making strategies (also called “dominant discourses” or “master narratives”) is also taken up in a type of discourse analysis called “positioning theory” (Bamberg, 1997b, 2003; Davies & Harré, 1990). Positioning and its analysis refer broadly to the close inspection of how speakers describe people and their actions in one way rather than another and, by doing so, perform discursive actions that result in acts of identity. We will return to the notions of positioning and acts of identity when discussing sociolinguistic and ethnographic lenses on identity below.

Despite some caveats, it should be clear that discourse (small or capitalized) is the place par excellence for negotiating categorical distinctions with regard to all kinds of identity categories—be it gender, sexuality, ethnicity and race, or nationality and immigration. What surfaces in our discussion is an existing tension between capital-D and small-d discourse perspectives in the space and importance alternatively given to macro or local phenomena in the formation and negotiation of identities. The tension between a perspective that views (personal and institutional) agency as constituted in terms of a direction of fit from global, structural phenomena to local actions versus one that emphasizes the direction of fit from local actions to the constitution of global phenomena is ultimately a productive one—one that requires further integration into the business of identity theorizing. However, although it may be desirable to combine these two perspectives into one that shifts back and forth in an effort to illuminate how meaning is “agentively experienced,” it may be necessary to keep in mind that they are perspectives—not to be confused with the phenomena as such.

A similar tension will resurface in our next section, where we turn to a discussion of how sameness and difference between self and others figure into the construction of identity and sense of self. We will work through a number of sub-disciplines of language analysis (e.g., sociolinguistics and ethnography) as they address (implicitly and recently more explicitly) the tension between small-d discourses (as operating within small-d in situ and in vivo contexts) and capital-D discourse (operating in capital-D institutional and communal contexts).

Stylistics, Sociolinguistics, and Ethnography: Integrating and Differentiating Self and Other

Research on styles and structures of texts was originally housed in the discipline of “literary analysis.” Texts, particularly literary texts, are typically viewed as consisting of form and content. Style of a text traditionally refers to a particular aesthetic patterning of rhetorical figures and lexico-syntactic patterns. A new approach to style was ushered in by Roman Jakobson’s (1960) groundbreaking model of language, in which functions of language were connected to different facets of a situated context—such as the use of the referring function of language for the production of speech genres such as descriptions or lists. Not only were the functions connected to aspects of context, but they were typically identified with more than one context, such that language was assumed to be multi-functional. Jakobson included poetics within the array of functions in order to add a lens that focuses onto the message itself. Along with incorporating more formal linguistic analysis into stylistics, Jakobson’s model led to widespread recognition of the multi-functionality of language and what this meant for the purpose of analyzing its use.

A clearer differentiation arose in the works of Halliday (1989) who distinguished between (i) the referential function of language (as referring to and naming objects in the world), (ii) the textual function (structuring texts in terms of their units so they can emerge as recipes or narratives), and (iii) the communicative/interactive function (providing a tool for interpersonal communication). The linguistic and stylistic make-up of texts and their structural units thus became the middle ground and connective tissue between the language function, identifying the actual grammatical and lexical choices that were made at the referential level of language use, and the intentional acts of communicating with others. In spite of the fact that this orientation toward language coincides with the commonsense conviction that the choice of particular linguistic devices is in the service of communicative intentions, and that this relationship becomes encoded in the text, reading intentions off the text is not straightforward: “there is no ‘understanding’ of texts as a semantic process, separate from, and prior to, a pragmatic ‘evaluation’ which brings context into play” (Widdowson, 2004, p. 35).

Recent discourse- and text-analytic developments have been influenced by the sociolinguistic assumption that linguistic variation is reflective and constructive of social membership categories. Likewise, the analysis of textual and stylistic features (cf. Coupland, 2001; De Fina, 2007; Eckert & Rickford, 2001; Georgakopoulou & Goutsos, 1997), especially in stylizations and styling, has brought to the fore a more agentive (though not necessarily conscious) speaker identification with particular uses of communally expressive forms and repertoires. Choices that index particular styles consist of linguistic features in close relation to metalinguistic, gestural, and bodily characteristics (including phenomena such as hairstyle or clothing). The interplay of these choices points to how users identify themselves subjectively and position themselves in terms of the community or subculture to which they belong or aspire. As such, stylistic choices and stylistic variation are constantly renewed and become deeply engrained with the expression of a personal, individual identity, as well as a group or community identity. Thus, stylistics and text analysis, originally operating on the internal make-up of (written) texts, have moved on to the analysis of the use of small-d repertoires as contextual cues for identifications with—or disengagement from—existing social patterns of capital-D discourses.

Traditional sociolinguistics has primarily been interested in linguistic variation across particular populations. The starting point for this type of investigation is the basic conviction that speakers have options as to how to present referential information. Thus, in terms of their lexical, syntactic, prosodic, and even phonetic selections of formal devices, speakers can either conform to, or deviate from, established standards. The preferences that are revealed in their choices usually characterize speakers along regional or socio-cultural dimensions of language use, marking them in terms of particular membership (social) categories. Work by LePage and Tabouret-Keller (1985) on processes of pidginization and creolization, for example, has interpreted speakers’ choices of linguistic varieties as tokens of the emergence of such social identities. Repeated choices in language use, as well as changes in these choices over time, signal “acts of identity in which people reveal both their personal identity and their search for social roles” (LePage & Tabouret-Keller, 1985, p. 14). Interactional approaches to sociolinguistics (Gumperz, 1982a, 1982b) similarly highlight the close relationship between language choices and identity categories such as gender, ethnic, and class identities as communicatively produced. Gumperz’s analyses of face-to-face verbal exchanges focused on the inferential processes that emerge from situational factors, social presuppositions, and discourse conventions, all of which work together to establish and reinforce speakers’ identifications with membership categories.

In recent articles and edited volumes, the different schools of thought that emerged from traditional sociolinguistics (e.g., Labov), interactional sociolinguistics (e.g., Gumperz), in overlap with ethnographic traditions (e.g., Gumperz & Hymes, 1964, 1972) have been reworked and partly transformed to develop more specific tools for the analysis of identity in discursive contexts (cf. Blommaert, 2006; De Fina, 2003; Johnstone, 1996, 2006; Schiffrin, 1996, 2006; Thornborrow & Coates, 2005). Similarly to recent trends within text-linguistic and stylization traditions, sociolinguists and ethnographers have developed new strategies to analyze more closely the use of speech patterns for processes of differentiation and integration, i.e., the use of small-d discursive means to position a sense of self vis-à-vis existing capital-D speech communities. Although identity in these approaches is typically not further theorized, the distinction between self and other, as integrating sameness and differences (individually and socially), is taken for granted as universally woven into the use of speech as socially occasioned.

The term membership categories is an offspring from Sacks’ early work on category-bound activities (Sacks, 1972, 1995). Authors within this tradition (see especially the work of Baker, 2002, 1997, 2002; and the collection of chapters in Antaki & Widdicombe, 1998a) have explored identities by use of membership categorization analysis (MCA), a branch of conversation analysis and ethnomethodology that pays close attention to the commonsense knowledge that speakers are invoking in their everyday talk. Sacks (1995) proposed that categories may be linked to form classes or collections, which he termed membership categorization devices (MCDs), and he attempted to tie these categories to local and situated activities, which he termed category-bound activities. Central to the analysis of speakers’ use of membership categorization devices, and what they accomplish in interactive situations, is the assumption that speakers engage in identity work: People establish identities in terms of doing age or doing gender (cf. Bussey, Chapter 25, this volume). In order to avoid prematurely imposing membership categories from the researcher’s perspective (as the outsider perspective), MCA proponents work analytically, as closely as possible, with speakers’ micro-level orientations (e.g., by use of gaze patterns) toward each other. It is at this small-d discourse level that speakers are assumed to sequentially fine-tune their interaction and, through this process, also make capital-D categories and ideologies visible for each other. And it is at this detailed, small-d discourse level (typically working from transcripts of conversations) that we can capture the interactional dynamics that are at work in accomplishing how communicative partners engage jointly in categorically differentiating and integrating their identities. Thus, categories in MCD serve as repertoires from which people can select different facets of identity, to which discourse analysts gain access analytically.

In contrast, traditional conversation analysis (CA) does not analyze the conversational patterns as aspects of broader social situations, focusing instead on discourse and interaction as more autonomous concepts. Consequently, CA researchers argue that it is necessary to “hold off from using all sorts of identities which one might want to use in, say, a political or cultural frame of analysis” (Antaki & Widdicombe, 1998b, p. 5.) and begin to ask “whether, when, and how identities are used” (Widdicombe & Antaki, 1998, p. 195, emphasis in original). According to this view, and in combination with the analysis of membership category devices, identities are locally and situationally occasioned, and they only become empirically apparent if participants in interaction actually “orient” to them. Thus CA, in combination with MCA, shares a commitment to the empirical study of in vivo small-d discursive practices through which particular capital-D social orders are said to be implied and coming to be visible. Consequently, the emphasis is on the analysis of naturalistic data, the way discourse and interaction take place in often very mundane, everyday settings, displaying the participants’ ways of making sense in these settings. Identities and sense of self are made relevant in interactions and oriented to by the way talk is conducted. Thus, identities are done—emerging in the here and now of the interaction.

Critical discourse analysis (CDA) bears a number of resemblances to MCA insofar as critical discourse analysts attend to categories within which, and by use of which, identities are framed. However, in contrast to MCA, identities are not seen as locally established by use of small-d discourse agents, but as aspects of larger capital-D political and ideological contexts (cf. Fairclough, 1989). Within this framework, identities are typically explored as power spaces in which the articulation of voice is “repressed.” For CDA researchers, the properties of speakers’ gendered or racial identities may play an important role in the discourse that is under construction, contributing to the discursive reproduction of, for instance, sexism or racism (see van Dijk, 1993). Thus, although CDA is primarily interested in the reproduction of power and the abuse of power in discourse, the identities that participants are said to bring to the interactive encounters, or that materialize in texts, may play important roles in this.

Narrative Identities—Constructing Constancy and Change

Narrative discourse takes up a special status for purposes of identity work and identity analysis. In addition to the functions of discourse for the construction of agency and self-differentiation, narratives add a temporal (and spatio-temporal) dimension to a sense of self and identity. Building on narrative theorists such as Bruner, Polkinghorne, and Sarbin, McAdams (1985, Chapter 5, this volume) has turned the assumption of selves plotting themselves in and across time into a life-story model of identity. He states that life stories are more than recapitulations of past events: They have a defining character. In his words, “our narrative identities are the stories we live by” (McAdams, Josselson, & Lieblich, 2006, p. 4). His approach, as well as other kinds of biographic approaches to identity analysis, however, has recently been criticized as overplaying the temporal dimension of identity construction, at the expense of the interactive and cultural role of discourse as the practice grounds for agency and self–other differentiation/integration (cf. Bamberg, in press a; Georgakopoulou, 2007). Because the biographic approach to identity is represented elsewhere in this Handbook (McAdams, Chapter 5, this volume), we focus our depiction of the contribution of narrative discourse to identity construction on describing a larger discursive perspective that attempts to integrate and merge sociolinguistic with ethnographic and conversational approaches to identity construction (see also Bamberg, in press b).

It is interesting to note that sociolinguists such as Le Page and Labov displayed an explicit interest in identity in their variationist approaches, but not in their narrative work. In Labov’s case, his interest in narrative analysis was more a by-product of his sociolinguistic studies that aimed to combat the linguistic prejudice found in Black English spoken in American cities in which poor African-Americans were disenfranchised. His early attempts to use “narratives as a method of recapitulating experiences by matching a verbal sequence of clauses to the sequence of events which had actually occurred” (Labov, 1972, p. 360) provided evidence that African-American male teenagers had full control of both syntactic and textual structures, but that Black English was a marker of differentiating black from non-black and of integrating a sense of black self within a black discourse community. His work on narrative has become not only widely discussed but also critically evaluated (cf. Bamberg, 1997a). Nevertheless, Labov’s (1997) continuing work on narrative turned into a “theory of … the narrator as an exponent of cultural norms” (p. 415, our emphasis), where the narrator became a more explicit target for the analysis of social and personal identity.

In an interesting contrast to Labov’s framework, Hymes (1974, 1981) established a different, though equally close, link between sociolinguistics and narrative and theoretically elaborated it in more recent writings (Hymes, 1997; 2003). By adopting a broader perspective on language, text, and context through the theory and practice of the ethnography of communication (Schiffrin, 1994, Chapter 5), Hymes’ program of ethnopoetics went further to explicitly suggest the analysis of speech patterns in the forms of verses and stanzas, taking fuller account of the performative aspects of language use as narrative performance and practice.

In recent attempts to integrate sociolinguistic, ethnomethodological, and—to a degree—critical discursive elements (cf. Bamberg, 1997b; 2003; Bamberg, De Fina & Schiffrin, 2007; Bamberg & Georgakopoulou, 2008; De Fina & Georgakopoulou, 2008; Georgakopoulou, 2006, 2007), narratives are typically analyzed as small-d stories and as discursive practices, i.e., in the way they surface in everyday conversation and other kinds of in vivo interactions where they form the locus of identities as continuously practiced and tested out. This approach allows exploration of self at the level of the talked about that reaches from a past into a present (as in the biographic approach) and at the level of tellership and performance in the here and now of small-d storytelling contexts. All three of these facets—content, form, and performance—thus feed into the larger project at work in terms of a capital-D global situatedness within which selves are usually positioned, i.e., with more or less implicit and indirect referencing and orientation to social positions and discourses above and beyond the here and now.

Placing emphasis on small-d stories allows for the study of how people as agentive actors position themselves—and in doing so become positioned. This model of positioning (see Bamberg, 1997b, 2003; Davies & Harré, 1990) affords us the possibility of viewing identity constructions as twofold: We are able to analyze the way the referential world is constructed, with characters (such as self and others) emerging in time and space as protagonists or antagonists, heroes or villains. Simultaneously, we are able to show how the referential world (of a past that is made relevant for the present) is constructed as a function of the interactive engagement. In other words, the way the referential world is put together points to how tellers index their sense of self in the here and now. Consequently, it is the action orientation of the participants in small storytelling events that forms the basic point of departure for this kind of functionalist-informed approach to narration and, to a lesser degree, to what is represented (or reflected upon) in the stories told. This seems to be what makes this type of work with small stories crucially different from biographical research. A small story approach is interested in how people use narratives in their in vivo and in situ interactive engagements to construct a sense of who they are, whereas biographic story research analyzes stories predominantly as representations of the world and of identities within those representations.

Identity as Discursively Constructed

Here we reflect back on discursive perspectives, and we focus on some of the common themes that have emerged in the different kinds of approaches discussed thus far, as well as their central implications for current and future research on identity.

Agency

Discursive perspectives on identity construction view the speaking subject as a bodily agent, i.e., in contrast to a disembodied mind. Participants in small-d discursive interaction—better: bodies-in-interaction—are the location where identities are construed in and through talk. Talk, of course, is more than words connected by the rules of grammar. Any analysis of bodies-in-interaction requires to make concomitant non-linguistic actions part of the analysis. Viewing the speaking subject as agentively engaging in small-d discourse, and in these activities as indexing positions vis-à-vis capital-D categories and ideologies, captures only half of the dilemma faced by subjects who are arguably constructing themselves. When choosing discursive devices from existing repertoires, speaking subjects face what we have termed the “agency dilemma” (Bamberg, in press a). Indeed, either speakers can pick devices that lean toward a person-to-world direction of fit or they can pick devices that construe the direction of fit from world to person. On one end of this continuum, speaking subjects view themselves as recipients, i.e., as positioned at the receiving end of a world-to-person direction of fit. Choosing devices from small-d repertoires that result in low-agency marking assists in the construction of a victim role or at least a position as less influential, powerful, and responsible and—in case the outcome of the depicted action is negatively evaluated—as less blameworthy. In contrast, picking devices from the other end of the continuum, speaking subjects position themselves as agentive self-constructors. Discursive devices that mark the character under construction in terms of high agency lend themselves for the construction of a heroic self, a person who comes across as strong, in control, and self-determined. In either case, depicting events in which a self is involved and placing this self in relation to others (as agent or as undergoer) require a choice of positioning; and the analysis of identity construction must attend to these choices as indexing how the agency dilemma is being navigated and a sense of self as actor or as undergoer comes to the surface.

A brief illustration, taken from Bamberg (2010), may help clarify what we mean when we talk about “agency navigation.” In an interview that John Edwards gave on August 8, 2008, on ABC’s Nightline,7 he presents himself as a hardworking young man—i.e., as highly agentive who was dreaming of doing something useful in society. In the course of the interview, however, he shifts this position and marks himself as being swept into popularity—losing his agency and thereby becoming less accountable for the transgressions that happened (cf. Bamberg, 2010, for a more detailed analysis of John Edwards’ interview).

Same Versus Different

A second theme identified by discursive perspectives on identity construction is the management of self-differentiation and self-integration. What is at stake here is that choices of small-d discourse devices often signal a position of the speaking subject in relation to others; others who are being referred to (in what the talk is about) and who are being talked to (in the speech situation under consideration). More specifically, category ascriptions or attributions to characters that imply membership categories, or even choices of event descriptions as candidates for category-bound activities, mark affiliations with these categories in terms of proximity or distance. Aligning with (or positioning in contrast to) these categories, speakers draw up boundaries around them—and others—so that individual identities and group belongings become visible. Thus, it is typically through discursive choices that people define a sense of (an individual) self as different from others, or they integrate a sense of who they are into communities of others. Although this can be done by overtly marking self as belonging to a social category—as in John Edwards’ case: “I grew up as a small-town-boy in North Carolina, came from nothing, worked hard”—most often the kind of category membership is hinted by way of covertly positioning self and others in the realm of being talked about (again, quoting from John Edwards’ interview: “people were telling me, oh he’s such a great person … you’re gonna go, no telling what you’ll do”). Thus, aligning with the moral values of others who come from nothing and are hardworking, and at the same time trying to explain how we differ from these same people, because we have violated their moral values (as in Edwards’ case by committing adultery), requires the navigation of how and to what degree we are the same and simultaneously differ from others. And giving descriptions of self and others or trying to explain their behaviors and actions, and whether this is done directly in terms of character attributions or in terms of action descriptions, identifications along the axis of similarity or differences between self and others are unavoidable.8

Self–other differentiation and the integration of speaking selves into constellations with others operate against the assumption that other and self can simultaneously be viewed as same and different. However, which aspect of sameness and difference is picked and made relevant in a particular speech situation is likely to vary from situation to situation and is open to negotiation and revision between conversationalists in local contexts. Some of these aspects fall under the traditional header of social identities and are said to be sorted out in terms of placing others and selves in membership groups, associating with particular groups favorably, comparing us (as the in-group) with other groups, and desiring an identity that is (usually) positively distinct in relation to other groups. However, the contrast or seeming contradiction between what is social and what is personal or individual dissolves away in discursive perspectives on identity construction: The personal/individual is social and vice versa. Discourse perspectives view the person empirically in interaction and under construction. They do not ask where the personal (individual/private) starts and where it becomes social; nor do they ask where the social (group/cultural/socio-historical) starts and whether or how it impacts on the individual. Of course, this is not meant to deny that there is a culturally shared sense of what counts as personal, private, and intimate vis-à-vis a space that is communally more open and public.

Constancy and Change Across Time

Speakers’ accounts of life as an integrated narrative whole form the cornerstone of what Erikson (1963) has called “ego identity.” Narrative, as we laid out above, seems to lend itself as the prime discourse genre for the construction of continuity and discontinuity in the formation of identity, given that it requires speaking subjects to position a sense of self that balances in between two extreme endpoints on a continuum: no change at all, which would make life utterly boring, and radical change from one moment to the next, resulting in potential chaos and relational unpredictability. As with the previous two dilemmas discussed thus far, speaking subjects are required to navigate this conflict by positioning their sense of self in terms of some form of continuity, i.e., constructing their identities in terms of some change against the background of some constancy (and vice versa). The choice of particular discursive devices, taken from the range of temporality and aspectual markers, contributes to the construction of events as indexing (potentially radical) transformations from one sense of self to another and constitutes change as discontinuous or qualitative leaps. In contrast, other devices are typically employed to construe change as gradual and somewhat consistent over time—leaving no third option on this continuum except the one that simply doesn’t require a story. Consider for instance stories that reason about (lay out and explain) one’s sexuality. Coming out stories of a homosexual identity can give shape to who-I-am in the form of a transformation—maybe even a relatively sudden one. However, they also can be plotted as continuous, where the speaker just didn’t know or notice his/her real sexuality, which all along (continuously) had been the same (though hidden or dormant). In contrast, John Edwards navigates the waters of change and constancy by maintaining that he is in his “core exactly the same person” he used to be when he was the boy who grew up poor and had high moral values, but that his “outside” underwent changes—brought about by the agency of others—that resulted in his moral transgression (for more detail, see Bamberg, 2010).

The contribution of narrative approaches to identity is that they replace the question of whether a person really is the same across a certain span of time or whether she/he has changed, with the analysis of how people navigate this dilemma constructively in their small-d discourse, particularly in their narratives in which they try to weave past and present into some more or less coherent whole. Here it is evident that the question is to a lesser degree what actually happened and to a much larger degree how constancy and change are constructively navigated. It is at this level where speaking subjects engage in discursive practices of identity maintenance, as well as in underscoring and bringing off how they have changed—unfortunately not always for the better. For us as discourse and identity analysts, narratives—particularly those embedded in their interactional small-d in vivo contexts—are the empirical domain in which identities emerge and can empirically be investigated.

Summary

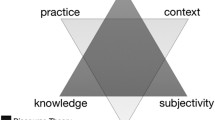

Discursive perspectives on identity construction and identity analysis distinguish between and clarify three analytic domains within which identity constructions are discursively accomplished: (a) navigating the two directions of fit—one in which the person constructs the world and the other in which the world constructs the person—in order to display a sense of who-I-am in terms of agency, (b) balancing one’s sense of being the same and different from others—and thereby practicing the differentiation of who-I-am from others together with the integration of who-I-am with existing membership categories, and (c) positioning oneself as same and different across time (and space)—and thereby constructing a sense of some continuity (and development) across one’s lifespan (or parts thereof). Choosing the “right” discursive devices enables speaking subjects to come to grips with these dilemmatic challenges, and analyzing these small-d discourse choices offers insights into the ways in which identities are occasioned and accomplished in local in vivo contexts. Thus, what from one angle appears to be a disadvantage of discursive approaches—namely that they do not appear to yield generalizable results—from another angle turns out to be their gain. From a discursive perspective, the descriptive detail and deeper insights into how the three dilemmatic spaces can be occupied and productively navigated outweigh the traditional call for reliability and generalizability. Using the lens of discourse and the lens of construction and bringing them to focus onto identity, what comes to the fore are discursive practices as the sites for identity formation processes—where the social and the personal/individual are fused and become empirical as situated, in vivo, interactive processes.9 Focusing our lenses on the interactive (and as such always psychosocial) nature of identity practices, detailing how identities are coming to existence and are maintained microgenetically (cf. Bamberg, 2008), how they are practiced and change over time, and feed our subjective sense of who-we-are as somewhat unitary beings, establishes a different kind of encounter with empirical material in new and unprecedented ways.

Illustration

In this section, we provide an illustration of how identities and their construction are approached from a discursive perspective. We have chosen a short stretch of interaction—what we term a “small story”—that consists of a brief account given by a 15-year-old male 9th-grader in the context of a group discussion with five of his peers and an adult male moderator. The actual account, which altogether does not entail much of a plot development or a script-break, is centrally about a 17-year-old male 11th-grader who is categorized as gay. The character depicted in this account is construed as talking (a lot) about his gayness (near his locker) (lines 22/23) and further categorized as associating more with girls than with other boys (lines 26/27). It will become clear that an assessment of what the story is about can more securely be made if we take into account why the story was shared, which requires an investigation into how it is interactionally embedded and jointly accomplished by the participants (Bamberg, in press b). We will illustrate how we proceed in our analysis by sequentially following the participants in their interactive positions vis-à-vis each other and discussing how, in this process, they orient toward capital-D discourses and differentiate themselves from third person others—here a gay boy. Our analysis centers around the discursive construction of a heterosexual male identity, individually (for James as the speaking subject) as well as a group identity that is fine-tuned by the participants as active participants in this conversation. We will try to document, wherever possible, how speakers orient toward the three dilemmas that we described as relevant cornerstones for discursive identity construction earlier in this chapter.

The topic at the start of this excerpt is whether there are gay boys in the school attended by the teenagers. In line 6, James contradicts Ed and positions himself as better informed about the current status of gay boys at their school and in line 9 backs up his position with his claim to actually know a few gay boys at their school. However, in midstream he self-repairs this claim to authority by changing knowing to having seen them (line 10). At this point, let us pause for a second and ask what is going on here. “Knowing someone” comes with the connotation of a certain kind of proximal or intimate recognition, maybe even acceptance. Having had visual encounters with a person—in contrast to the claim of “knowing this person”—implies more distance, less proximity, and less intimate recognition; maybe to be able to recognize this person among others, but not much more. James’ downgrading to only having seen a few gays at his school asks for further commentary. One possible explanation for his change in position vis-à-vis gay schoolmates may be that he wants to more clearly spell out his proximity/distance (position) vis-à-vis the membership category labeled gay; that is, he may wish to avoid being heard as someone who has “gay friends” or being construed as gay himself. However, he is challenged by Ed and Alex in their subsequent turns. Both challenge James’ criteria for categorizing others as gay on the grounds of “spotting gays” by simply seeing (lines 11 and 12)—thereby calling into question James’ claim to authority on issues of sexuality and potentially charging him as prejudicial. James, in line 13, returns the question with a similar phrase: how do I know <not: “how can I tell”> they’re gay? Thereby he acknowledges that Ed and Alex potentially saw through the maneuver behind his modified “knowing” and also recognizes that “seeing” members of a particular membership category is still a categorization and counts as a kind of “knowing;” but he formulates his answer in a display format that originally signals “not to have understood” Alex and Ed’s challenge—then, after Ed insists (line 14), followed by a more elaborate answer.

James’ more elaborate response, starting with line 15, could have gone into a number of

-

Excerpt: How Do I Know They’re Gay?

-

1 Ed there ARE some gay boys at Cassidy

-

2 Mod do they (.) do they suffer in eh at your schools

-

3 do they are they talked about in a way//

-

4 Ed I don’t think there are any

-

5 I don’t think there are any openly gay kids at school

-

6 James ah yeah there are

-

7 Ed wait there’s one

-

8 there’s one I know of

-

9 James actually (.) I know a few of them

-

10 I don’t KNOW them but I’ve SEEN them

-

11 Ed how can you tell they’re gay

-

12 Alex yeah you can’t really tell

-

13 James no (.) like how do I know they’re gay <rising voice>

-

14 Ed yeah

-

15 James well (.) he’s an 11th-grade student (.) the kid I know

-

16 I’m not gonna mention names

-

17 Ed all right (.) who are they <both hands raising>

-

18 James okay um and I’m in a class with mostly 11th-graders

-

19 Josh and his name is <rising voice>

-

20 James ah and ah and um a girl

-

21 who is very honest and nice

-

22 she has a locker right next to him

-

23 and she said he talked about how he is gay a lot

-

24 when she’s there (.) not with her

-

25 like um (.) so that’s how I know

-

26 and he um associates with um a lot of girls

-

27 not many boys

-

28 a lot of the (.) a few of the gay kids at Cassidy

different directions. For instance, a potential dispute could have evolved over what counts as activities or behaviors that qualify as typically gay (membership category-bound activities). However, when Ed upheld his challenge (line 14), James responds with a turn initial well, a general shifter of frames that also signals the intention to hold the floor for an extended turn (Schiffrin, 1985). He shifts focus from plural gays—from who they are and generically do—to an unspecified singular he 10—to a past event—presumably what he, now as a specified member of the “gay category,” once did. This third person he is now specified as an 11th-grader, and his name is explicitly “not being mentioned.” The rhetorical device of “explicitly not mentioning” is a clever way of displaying sensitivity and discreteness, thereby indexing the interactive business at hand as not gossiping. However, at the same time, this very same device of withholding information designs audience expectations toward something that is highly tellable—if not gossipy. Ed’s and Josh’s forceful requests (lines 17 and 19) to hear names bespeak exactly this. However, instead of specifying the person, James (in line 18) moves further into descriptive (background) details: that he has class with mostly 11th-graders, and thus—in contrast to the other five participants, who all are 9th-graders—may not only be more knowledgeable of the boy he had previously introduced (and left unspecified thus far) but also be more knowledgeable in general. At the same time, this information may serve the function to clarify why he “knows” and the other participants in this round do not.

To summarize, the interactional setting in which the upcoming account is grounded is the following: James, who seemed to have successfully laid claim to knowing better and more about a gay population at their school, is challenged for potentially drawing on prejudicial categories in his segregation of gays from non-gays. This leads to James’ response in setting the scene that orients toward a more elaborate account in the form of a small story. He introduces a specific character, presumably a gay 11th-grader, and opens up audience expectations for what is to come next as a sequence of descriptions and evaluations (about the character in question) which (hopefully) clarifies how and why James is able to uphold authoritative judgments on gay issues. In other words, with his subsequent story James is expected to reclaim the authority on the gay–hetero distinction that he had laid claim to have experiential access to—which had been called into question.

The storied account unfolding in lines 20–24 and 26–28 does not consist of a typical plot line or plan break, but of two pieces of further descriptive information. First, a description of the 11th-grader as someone who talks a lot about his being gay—and, as the elaboration shows, openly, i.e., in the presence of overhearing audiences; and second, as someone who hangs out at school more with girls than with boys. These pieces of information position the gay boy in (grammatical) subject position as the agent, i.e., as willfully, intentionally engaging in these category-bound activities, which are said to have been habitually occurring. Both pieces of information arguably provide evidence for the alleged person’s membership in the category “gay” and in this sense can be said to relate to the point the audience may be waiting for. James seems to make good on this expectation in line 25: so that’s how I know.

More interesting, however, is the way this information is garnered and sequenced. James presents the information about the gay boy as “second-hand knowledge.” He uses a form of “constructed dialogue” (here in the form of “indirect speech,” i.e., as a summary quote) to recreate the action in question (having seen or knowing about gays in their school) through the lens of talk of someone else who is held socially accountable. He introduces a nameless witness, who is characterized as female, honest, and nice, and as having her locker right next to the boy whose sexual identity is at stake in this account. It is this girl who is presented as overhearing the speech actions of the boy that give rise in the unfolding story to the characterization of “gay” category activities. James, having reportedly heard this from a female character, also may imply that he is able to talk openly with females about such issues. In sum, James’s attempt to regain his credibility and authority (on “gay” issues—though probably also on issues of sexuality in general) rests on his presentation of an overhearing eyewitness and relays the crucial information as hearsay. By placing his reputation as knowledgeable in the hands of this reliable witness, he is able to successfully “hide” behind her. Thus, the question arises of how he manages to come across as believable in spite of the fact that he himself does not have any first-hand knowledge—at least not in this particular case. He has not “seen” (witnessed) gayness as he had claimed in line 10, and his former statement of “knowing” now is being modified to what others have told him. So how does he do this without undermining and having to withdraw his original claim of “knowing by having seen?”

James seems to be accomplishing several activities at the same time. First, when openly challenged on his ability to make a differentiation between gays and heterosexuals, he successfully (re)establishes his authority. He lists a witness’ account and rhetorically designs this witness as reliable. This witness is “honest” (in contrast to “a liar”) and “nice” (in contrast to “malicious” or “notoriously gossiping”). In addition, giving details such as the fact that her locker is “next to his” contributes further to the believability of James’ account (on the role of detail in narrative accounting, see Tannen, 1989/2007). Furthermore, the characterization of the boy as talking “a lot” about his gayness makes it difficult to (mis-)interpret the girl’s (and James’s) accounts as potential mis-readings—or worse, as simply relying on stereotypes about gay behavior.

Second, the introduction of his witness as a girl (note that James could have left the gender of this person unspecified), and also as one who did not talk directly to the gay boy, further underscores how James “wants to be understood:” In line with his corrective statement in line 10 (“just having seen gay boys, not really knowing them”), having a close confederate who is also relationally close to the gay boy (and speaking with him “a lot”) could make this confederate hearable (again) as in a close kind of knowing relationship with a “gay community.” Thus, designing this confederate as a girl, who is not even being addressed by the gay boy when he talks about his sexual orientation, makes it absolutely clear that there is no proximity or any other possible parallel between this boy’s sexual orientation and James’s. A girl is a perfect buffer that serves the role of demarcating the difference in sexual orientation between James and his gay classmate.

Third, James’ staging of the “fact” at the end of his small story that this boy “associates with a lot of girls and not boys” (except with a few other gay kids at school) is very telling. While the “fact” that this kind of category-bound activity (that gays hang out with girls) may be an observable, empirical “fact,” and therefore may come across as substantiating his claim “I have seen them,” it is also easily hearable as a stereotypical and potentially prejudicial judgment. Had James mentioned this at the beginning—i.e., had he prefaced that he had seen one boy hanging out predominantly with girls in the form of an abstract or an orientation for why he is sharing his small story about the girl at the first place—he would have been heard as expressing a (stereo-typical) view of a heterosexist, antigay capital-D discourse, potentially resulting in further challenges from Ed and Alex as “loosely speaking,” not differentiating carefully enough, or even being prejudicial. However, placing this category-bound activity at the end of his small story about the girl, and giving it the slot of the coda, he uses this structural narrative device to finish off his storied account and orients the conversation toward a new topic, namely why it is that gays hang out more often with girls (and this is actually what happens in the talk that follows). In other words, this way of strategically sequencing his “evidence” allows James to epitomize the category of gays by having captured the individual in relation to the aggregate. This move in turn helps James to draw up and position himself within the group boundaries of “his peers” by drawing a boundary between “them” and “us.” The intentionality, and therefore responsibility, for not hanging out with heterosexual boys is placed squarely in the court of them, the gay kids; not us, the heteros. Note that the facts that James constructs with lines 26–28 could have been constructed by placing agency in others’ courts—such as “many girls associate with him,” or “not many boys associate with him,” or even more bluntly: “we rarely associate with him.”

In sum, James’s story allows him to accomplish multiple things: When openly challenged that he can differentiate gays from non-gays by simply “seeing” them, his story enables him to re-establish his identity as knowledgeable and reliable; furthermore, it helps him to fend off the interpretation of coming across as gossiping and being heard as prejudiced—as outright antigay or homophobic. However, and more importantly, his story allows him to carefully construct a sense of who-he-is as heterosexual and straight. It is in this sense that his story can be said to borrow and enact masculine norms and a sense of heteronormativity. However, as we would like to argue, this sense of a heteronormative self—as well as his sense of self as an authority on “gay issues,” a non-gossiper, and as someone who is not homophobic and prejudiced—are all active accomplishments of the participants who in concert put these norms to practice. They are achieved by how this story is situated and performed by use of small-d discourse devices within this very local setting. Thus, it is the situation that determines the logic or meaning of the norms being circulated, and not the boys’ cognitions or previously established concepts that they seem to have acquired elsewhere and now “simply” reproduce in their interactive encounters. And it is in this sense that the boys (as members of the membership category “heterosexual boys”) are both producing and being produced by the routines that surround and constitute these kinds of small-d narratives-in-interaction. And although our particular “small story” in a strict sense is the response to the challenges by Ed and Alex (lines 11 and 12), it answers a number of other identity challenges that are recognizable in the way the story is made to fit into the ongoing negotiation. It should be stressed that this particular local “small story”—as an exercise in maneuvering through the challenges of gossiping, homophobia, and heteronormativity—is simultaneously a practice of negotiating competing ideological positions. It is in situations like this that not only children and adolescents but also adults across their lifelong process draw on multiple positions; positions that can be used to signal complicity with existing master narratives, to counter, or to convey neutrality vis-à-vis them. Practicing these kinds of “small stories”—as a sub-component of discursive practices—is an indispensable stepping stone in the identity formation process of the person.

Concluding Remarks

The above illustration has laid out some of the procedural steps of how identity construction may be analyzed from a discursive point of departure. One of the guiding assumptions was to show how participants in their discursive practices navigate what we had called identity dilemmas. With regard to the navigation of sameness and change across time, the stretch of discourse chosen was relatively unrewarding: Although the events reported by James were past events, they were not used to reveal or document changes in terms of a former position that was replaced by a new one. He presented himself as “the same” back-then and here and now, i.e., as holding the same position with regard to what counts categorically as gay and what category-bound activities follow from this label in the past (when he presumably heard the story) and now (the conversational situation under scrutiny). In sum, he simply made a past event relevant for the present, but the past did not lead to or result in any change. We refer the reader to other examples where this type of identity navigation is more clearly exemplified and related to the navigation of the other identity dilemmas (cf. Bamberg, 2010, in press b; De Fina, 2003; Schiffrin, 1996).

With regard to the differentiation between self and other, we were able to show how James and his friends were navigating the territories of hetero- and homosexuality, but at the same time speaking authoritatively and coming across as non-prejudicial. The positions taken up in terms of how he and his friends differentiate themselves vis-à-vis gay boys (but also girls) and how they relate in terms of similarities vis-à-vis others and among themselves as a group reveal insights into the repertoires of identity formation processes and how these repertoires are negotiated and practiced in vivo and in situ. How these positioning practices microgenetically feed into next and new practices in subsequent interactions and storytelling situations cannot be detailed here; again, the reader is referred to other publications that follow up on changes in discursive practices in ontogenesis (cf. Bamberg, 1987; 1997c; 2000a; 2000b; Bamberg & Damrad-Frye, 1991; Berman & Slobin, 1994; Georgakopoulou, 2007; Korobov, 2006; Korobov & Bamberg, 2004).

Navigating one’s personal involvement, proximity, and affiliation in terms of the agency dilemma, we could follow James’ balancing acts between coming across as authoritatively speaking on matters of sexuality, avoiding to be heard as prejudicial, and simultaneously demarcating a strong sense of his heterosexual identity. Positioning oneself (as the speaking subject) and others (in our example the gay other as well as the female bystander) in affinity relations—closely or distant—as agentively involved or as passive recipients—are important practices when it comes to staking out a world of moral values. Drawing from discursive repertoires to mark outcomes of actions as caused by volition, unintended accidents, or unwillingly tolerated reveals a horizon of subjective viewpoints and values—often implying moral and ethical standards that are overtly embraced or covertly implied. Consequently, when analyzing how speakers (together with their audiences) engage in navigating who is at fault or blameworthy versus who is innocent and virtuous (or just uninformed and naïve)—and analyzing these positions in the realm of differentiating oneself from others along particular membership categories—here gay versus hetero—reveals a wealth of insights relevant for how identity is discursively forming in situ and in vivo, probably practiced and ritualized over time, and feeding into a sense of who-we-are across situations as a seemingly unitary subject.

Fusing the lenses of construction and discourse onto identity results in a view of the person as actively–interactively—and therefore always socially—involved in the relational constitutive process of answering the who-am-I question. This dynamic and process-oriented perspective views the person as engaged in living their own constructions—thus, the person is actively–interactively involved in negotiating, modifying, sustaining, and changing their sense of who-they-are by making use of discursive means that humans before and around them (and they themselves in previous practices) have constructed and kept in use as meaningful. Of course, it is possible to cut into these ongoing engagements, focalize on the person, and take a particular developmental moment to have emerged as “the product” of those changes and modifications, and possibly even posit this as an “internal structure” that holds the person together. Of course, it is equally possible to stop this emerging process and pose the question what societal factors, social groupings, or contextual features come into question as determining what we take this “personal identity” to be at this moment. However, we have purposely chosen to view identity construction as taking place in discursive practices that are first of all singular acts and taking place in vivo and in situ, with the person as an agentive part in this. Drawing on given discursive resources, as we have laid out in our illustration, people repeat and reiterate regulatory discursive performances. We suggest that these performances gain a certain durability and stability over time—up to a point where they appear to become solid and seemingly foundational for what we take to be a unitary sense of self.

Both discursive and constructive lenses have brought to the fore the social–relational constitution of identity, the way it emerges under the force of two directions of fit, the person as constructing him/herself in small-d discourse, on the one hand, and as being constructed by capital-D discourses, on the other hand. Our approach in this chapter has been to illustrate how participants in interaction make use of existing discursive repertoires and attend to or make relevant how they position themselves vis-à-vis pre-existing capital-D discourses. As we tried to argue in our introductory section, there are other discursive approaches that give more license to capital-D discourses and their impact on what and how people can and cannot do in small-d discourse contexts (e.g., critical discourse analysis). We purposely highlighted in the constructionist approach presented here that the discursive meaning-making tools, although having their own history in socio-cultural practices, are not fixed and require occasions of use and continuous practice by active agents. It is along those lines that we favored analytic procedures that work up from in situ and in vivo examples and spell out microgenetically how meaning-making tools are put to use. Starting from these levels of phenomena, the project is to see how such situated in vivo practices solidify and result in identities that, on the one hand, give the appearance of a unitary and relatively stable sense of self but, on the other hand, “are looser, more negotiable and more autonomously fashioned” (Muir & Wetherell, 2010, p. 5).

Notes

-

1.