Abstract

Research has consistently shown that expatriates are regularly assigned to all parts of the world without much cross-cultural training. This is regrettable since cross-cultural training intends to train individuals from one culture to interact effectively with members of another culture and to predispose them to a quick adjustment to their foreign assignments. Without much choice, lacking adequate host cultural and institutional insight, expatriates may have to resort to the same behavioral repertoire as they used in their home country without adjusting to the local norms and practices. This could have negative, if not disastrous, consequences for the expatriates themselves as well as for the foreign operations to which they belong. This chapter uses China as a critical test case as an expatriate destination with possible implications for cross-cultural training in general and in particular for the training of expatriates for other culturally challenging host locations. Appropriately, there is an initial discussion of whether cross-cultural training works or not and the content of cross-cultural training. Succeeding that, based on a number of recent empirical investigations, new dimensions of cross-cultural training are discussed. This is done by applying a systems view of expatriates and various aspects that may affect their cross-cultural training. To begin with, individual dimensions that have to do with the expatriates themselves are discussed. Following that, organizational factors are examined. The succeeding subsection deals with situational circumstances and the section ends with country-level aspects. From the empirical observations and research results of the new dimensions of cross-cultural training, five major conclusions are drawn: cross-cultural training works, culture-specific cross-cultural training may be preferable, cross-cultural training could be custom-made, recurring cross-cultural training may be necessary, and everybody may need cross-cultural training.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

In the age of globalization, there is a wide range to the process and practice of global work. Many individuals work in new cultural surroundings on a temporary basis in many capacities, for long or short periods and for various reasons. Belonging to commercial firms or non-profit organizations, they have at least one thing in common: the cross-cultural encounter which may substantially impact on what they will achieve in the host location. Regardless of their specific circumstances, this chapter will label such individuals “expatriates”. Surprisingly, research has consistently shown that expatriates are regularly assigned to all parts of the world without much cross-cultural training at all (Brewster, 1995; Hutchings, 2005; Selmer, 2000). This is regrettable, since cross-cultural training entails training individuals from one culture to interact effectively with members of another culture and to predispose them to a quick adjustment to their foreign assignments (Brislin & Pedersen, 1976; Black, Mendenhall, & Oddou, 1991). Without much choice, lacking adequate host cultural and institutional insight, expatriates may have to resort to the same behavioral repertoire as they used in their home country without adjusting to the local norms and practices (Black & Porter, 1991; Lawson & Swain, 1985). This could have negative, if not disastrous, consequences for the expatriates themselves as well as for the foreign operations to which they belong.

The purpose of this chapter is to uncover and discuss new dimensions of cross-cultural training based on recent empirical research on expatriation. Since new insights are continually gained regarding expatriates and their assignments through ongoing empirical research, such new knowledge may contribute to more effective planning and implementation of cross-cultural training, and hence could further increase the relevance of cross-cultural training. Many of the new research findings in this chapter are gained from studies of expatriates based in China. This country has an extraordinary economic development record that has attracted the attention of the Western world. On the other hand, China may be experienced as a very challenging host location. From a Western perspective, China is frequently regarded as the most foreign of all foreign places. Chinese culture, institutions, and people may appear completely baffling (Chen, 2001). In addition, the development and practices of Chinese management have been heavily influenced by the ancient cultural traditions of the country (Fang, 1999; Lowe, 2003; Wang, 2000) and there could be a risk of severe culture shock among Western expatriates (Kaye & Taylor, 1997). Hence, it may be a good idea to draw on experiences of Western expatriates in China since there seems to be a substantial need for effective cross-cultural skills for westerners who live and work there. This way, cultural and social differences and ensuing problems become more visible and easier to detect. Hence, China, to a certain extent, can be seen as a critical test case with possible implications for cross-cultural training in general when assigning expatriates to the rest of the world, and in particular for cross-cultural training of expatriates in other culturally challenging host locations.

The chapter proceeds with a discussion of whether cross-cultural training works or not, and its content. Succeeding that, based on a number of recent empirical investigations, new dimensions of cross-cultural training are discussed. The chapter ends with five major conclusions regarding cross-cultural training for expatriates and inpatriates alike.

Does Cross-Cultural Training Work?

Initially, it may be relevant to consider the fundamental question whether cross-cultural training is a worthwhile activity to undertake for organizations assigning expatriates abroad. The answer depends to a certain degree what cross-cultural training is and what criteria should be used to determine its effectiveness. It has been suggested that cross-cultural training is more efficient in creating knowledge and trainee satisfaction than changing behavior and attitudes and in improving adjustment and performance (Mendenhall et al., 2004). Furthermore, mostly due to methodological shortcomings and involving respondents other than expatriates (Kealey & Protheroe, 1996), it is not clear whether cross-cultural training can equip expatriates with what they need in the host culture, despite the numerous studies that have addressed the issue (Black & Mendenhall, 1990; Deshpande & Viswesvaran, 1992; Tung, 1981). For example, many studies do not even meet the minimal requirements of comparing experimental groups with control groups and neither do they specify pre- and post-training measures of changes in knowledge and skills (Kealey & Protheroe, 1996). However, more recent research involving business expatriates found supporting evidence for the beneficial effects of cross-cultural training. Findings of a mail survey to expatriates in China, involving most major Western European countries, indicated that expatriate managers who had received training adjusted more quickly in their assignments and were more satisfied with these assignments than those who had not received any training (Selmer, 2002d). The positive effect of cross-cultural training on the adjustment of expatriates has subsequently been corroborated by other researchers (Waxin, 2004; Waxin & Panaccio, 2005).

Content of Cross-Cultural Training

A pertinent distinction within the field of cross-cultural training is between culture-general and culture-specific training. This is a debated difference and there are proponents both for sensitivity training generally sensitizing expatriates to cross-cultural differences and their consequences (Brislin, Cushner, K., Cherrie, C. & Young, 1986; Brislin & Pedersen, 1976; Kraemer, 1973) as well as conveying more particular information targeting a specific national culture, and actually providing culturally-specific knowledge (Albert, 1983; Fiedler, Mitchell, & Triandis, 1971; Leong & Kim, 1991). Although a culture-specific approach has come to dominate cross-cultural training (see Bhawuk & Brislin, 2000, for an historical review of cross-cultural training), recent empirical evidence in support of the effectiveness of such an approach has been provided by Selmer (2002c). Investigating Western expatriates in Hong Kong, he found that previous experience in other locations in Asia did not facilitate their adjustment to Hong Kong, and neither did previous assignments outside Asia. The only thing that helped adjustment to Hong Kong was experience from that very location, suggesting that culturally unrelated prior international experience may be irrelevant, while the strongest impact may be gained from location-specific experience. These findings have subsequently largely been supported by other researchers (Takeuchi, Tesluk, Yun, & Lepak, 2005). This could be a crucial insight since location-specific experience may be regarded as the most perfect cross-cultural training possible. What can be better than experiencing the real thing? That observation amounts to a significant argument in favour of culture-specific cross-cultural training. The obvious practical implications of these findings are that expatriates should not only go through cross-cultural training once in their career, but for each and every new foreign assignment they embark on. If past lessons learned have limited transferability, repeated cross-cultural training to acquire social skills appropriate to a culturally unfamiliar host environment may be worthwhile (Selmer, 2002c).

Although the evidence in favor of a culture-specific cross-cultural training approach may be clear, recent research on expatriates has uncovered a number of particular circumstances and new dimensions associated with international assignments. These new dimensions could be considered in the design of culture-specific cross-cultural training programs in the future.

New Dimensions of Cross-Cultural Training

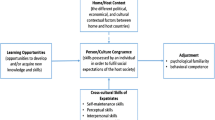

This section of the chapter is organized according to a systems view of expatriates and various aspects that may affect their cross-cultural training. Initially, individual dimensions that have to do with the expatriates themselves are discussed. Following that, organizational factors are examined. The succeeding subsection deals with situational circumstances and the section ends with country-level aspects.

Individual Dimensions

Psychological Barriers to Adjustment

There is a wealth of evidence suggesting that many Western expatriates could find their assignment to China frustrating (Björkman & Schaap, 1994; Kaye & Taylor, 1997; Sergeant & Frenkel, 1998). However, the origin of some of these difficulties could rest with the expatriates themselves. They may have psychological barriers to adjust to life and work in China. Expatriates may feel inept at dealing with the Chinese reality or they could simply ignore it due to lack of interest. Expatriates with such psychological barriers may not adjust well to China, or any other foreign location, since they cannot achieve a real understanding of the conditions in the host country. In a study of Western expatriates in China, results showed that both perceived inability to adjust and unwillingness to adjust among newcomers seemed to affect at least some aspects of adjustment. However, these effects did not appear to be stable over time as there were no such effects in the case of long-stayers in China, suggesting that in the long run both inability and unwillingness to adjust may be of little importance (Selmer, 2004).

Cross-Cultural Training Implications

Although psychological barriers to adjustment may become less significant over time, much damage may occur during the settling-in period in the foreign assignment. It may therefore be worthwhile to administer cross-cultural training to try to modify expatriates’ inability and unwillingness to adjust to a foreign location. To deal with perceived inability of the expatriates to adjust, and to enhance their confidence, a focus on salient cross-cultural differences to overcome in the host location may be helpful. Regarding unwillingness to adjust, cross-cultural training could instead focus on creating motivation for the individuals to modify their attitudes and behavior.

Coping Strategies for Successful Adjustment

Not only in China, but expatriation in general could be a stressful experience for the individual, and expatriates’ means and ways of coping with that stress could affect how well they adjust to living and working abroad. The notion of coping refers to an individual’s cognitive and behavioural efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the person’s resources (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). The literature typically makes a distinction between problem-focused and symptom-focused coping strategies (Folkman, Lazarus, Dunkel-Schetter, DeLongis, & Gruen, 1986; Folkman & Lazarus, 1980; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Pearlin & Schooler, 1978). While symptom-focused coping strategies intend to regulate stressful emotions, problem-focused coping strategies are applied to change the problematic person-environment relation that is perceived as the cause of the stress felt. In other words, using symptom-focused coping strategies, individuals attempt to minimize anxieties through physical or mental withdrawal from the situation or by avoiding the problem. In applying problem-focused coping strategies, a person tries to face the problem in order to change the situation (Folkman et al., 1986). In a series of studies of coping strategies and adjustment of Western expatriates in China, both male and female, empirical findings indicate support for the proposition that problem-focused coping strategies could enhance expatriate adjustment, whereas symptom-focused coping may be detrimental to such adjustment (Selmer, 1999a, 1999b, 2001b, 2002b; Selmer & Leung, 2007). For example, Selmer (2001b), investigating Western expatriates in Hong Kong, found a clear positive association between problem-focused coping and all of the studied measures of adjustment, as well as a negative relationship between symptom-focused coping and the investigated dimensions of adjustment.

Cross-Cultural Training Implications

Obviously, expatriates could benefit from being informed that problem-focused coping strategies are more effective than symptom-focused ones and could be trained in ways of problem-focused coping as well as avoidance of symptom-focused coping. An example of the former type of strategy is to try to solve culture-related problems or misunderstandings with host country nationals, and an example of the latter is home country escapism, reminding oneself that some day one will be living back in one’s home country, as a way to feel better about the current assignment.

Matching Personal Expatriate Characteristics with a Host Culture

Despite the importance to the assigning organization that the expatriate achieves a satisfactory work performance on the foreign assignment, not many studies have tried to directly assess expatriates’ performance at work, let alone linking work performance to personal characteristics of the expatriates. Instead, much of the expatriate literature has focused on the adjustment of expatriates examining personal characteristics that may facilitate or mitigate international adjustment in general, regardless of destination (Caligiuri, 2000; Mamman & Richards, 1996; Takeuchi et al., 2005). However, in contrast to such studies which explore personal characteristics of expatriates that in general may affect their work outcomes, Selmer, Lauring, and Feng (2009) attempted to match a certain personal characteristic of expatriates with a specific host culture. As opposed to the predominant belief in the West, in Chinese-dominated societies there may be a positive relationship between age and perceived possession of high-quality personal resources. That attitude towards old age may carry over to expatriates in Chinese societies. The self-efficacy of such individuals may be enhanced by being treated in a serious and respectful manner, and this supportive environment surrounding the expatriate manager may contribute to an improved job performance. Investigating Western expatriates in Greater China, Hong Kong, mainland China, Singapore and Taiwan, results showed that the job performance of the expatriates had a positive association with their age.

Cross-Cultural Training Implications

For expatriates destined for a Chinese cultural context who are unaware of the potential positive reactions of host country nationals to their mature age, learning and practicing how to exploit and take advantage of such behavior of the locals may be beneficial. This may also be in the best interest of the assigning firm since business expatriates are sent to foreign locations to perform certain work tasks. To make the expatriates aware of how they can perform better on the job in a Chinese cultural setting by making use of their older age could be a priority by the assigning organization.

Language Proficiency and Adjustment

Communication is crucial to management. But communication depends on a common language, a condition seldom existing in many international organizations. This could be the origin of many problems (Feely & Harzing, 2003). While language communicates, it also “ex-communicates”; that is, it only includes those who share the same tongue; everyone else is excluded (Fantini, 1995). This is especially so when mutually incomprehensible languages meet to create a formidable language barrier, such as the one encountered by many Western expatriates in China. Although the standard of English proficiency is rising in China, using English in conversations with Chinese host nationals may be very difficult due to a lack of much common vocabulary. But even between relatively fluent speakers, the interaction could be very deceptive as it may obscure cultural differences. Although a business conversation may be conducted in a second language, English, participants certainly think in their own language according to their own cultural norms, which may not be fully comprehended. Instead of being an efficient vehicle of communication, the “common” language of English becomes an obstacle for true understanding (Liu, 1995; Scheu-Lottgen & Hernandez-Campoy, 1998). For example, Chinese speaking practices often lead others to (mis)perceive Chinese people as shy, indirect and reserved, or as evasive and deceptive. Such perceptions unavoidably create communication problems between Chinese and others (Gao, 1998), even if both sides use English. Therefore, proficiency in the Chinese language, including speaking practices, may promote the adjustment of foreign business expatriates in China, not only by improving their direct communication with host nationals in Chinese, but also by making their interactions in English more effective. Although this seems to be a question that is almost too obvious to pose, that is, does language ability enhance the ability of expatriates to adjust to the work and social environment, the answer regarding China is not really known through previous research. Selmer (2006b) investigated Western expatriates assigned to China and, controlling for the time expatriates had spent in China, he found that their language ability had a positive association with all the studied measures of their adjustment.

Cross-Cultural Training Implications

Expatriates departing for another country where English is not the norm must realize that learning the basics of that country’s language should be viewed as part of the assignment (Dolainski, 1997). The importance of language training for Western expatriates is apparent in a location like China (Björkman & Schaap, 1994). Managers would probably be in a better position if they could make themselves understood in Putonghua, the spoken national language of the Chinese mainland, or in the local dialect at their place of assignment (Selmer & Shiu, 1999). It is not necessary to master the foreign language to perfection, as demonstrating even very basic skills (survival language), as well as elementary speaking practices, may connote the message to the locals that the expatriate really cares to make an effort to understand the host culture (Brislin, 1994; Zimmermann, Holman, & Sparrow, 2003). Unfortunately, language training, which should be a part of cross-cultural training, is identified in the literature both as being essential for successful adjustment as well as being badly neglected by international business firms (Aryee, 1997; Black & Mendenhall, 1990; Brewster, 1995). The empirical results underscore the emerging literature on language training as part of expatriate preparations, as well as other human resource management responses by international organizations. Although it is not possible to claim, for example, that all Western expatriates should have 6 months of Chinese language learning and follow-up study in China, the potential value of language training of expatriates in very “foreign” locations cannot be doubted. However, a myriad of other considerations will likely determine the specific details of such training. The cost-effectiveness of expatriate language training is just one of the many criteria international organizations may want to apply (Hayet, 2000). However, the difficulty of achieving high levels of proficiency, especially in non-European languages should not be underestimated (Bloch, 1995). Organizations may take the position that training high-level employees in a foreign language, such as Chinese, does not make much sense since it is a large investment with high front-end costs, not to mention the required sacrifice in time and effort by the individual. Top officials and executives may harm their careers by taking time off to study a language. Besides, it could be difficult to fit language training into the career ladder (Weber, 2004). So, although the empirical findings support language training in general, the necessity of expensive, tiring and time-consuming Chinese language training for expatriates is a decision for the specific organization to make.

Organizational Dimensions

Assignment to Tough Organizational Contexts

The literature on how the effectiveness of cross-cultural training may be influenced by various circumstances at the location of the foreign assignment is very scant. The distinction between different organizational contexts in assessing the effect of cross-cultural training is a novel approach. In a pioneering study, incorporating the impact of organizational abode on the effectiveness of cross-cultural training of business expatriates, Selmer (2005a) examined the differential effects of cross-cultural training on the adjustment of Western expatriates in international joint ventures and other business organizations in China. As elsewhere, international joint ventures in China are usually managed jointly by the local and foreign parent companies, both seeking “due representation” in the top management group (Björkman & Lu, 2001; Hambrick, Li, Xin, & Tsui, 2001). Besides involving the usual problems of partners having their own expectations, objectives and strategies, top executives in international joint ventures in China usually differ widely in national origins, cultural values and social norms (Li, Xin, & Pillutla, 2002). Hence, the challenges facing Western expatriates in international joint ventures in China could be extraordinary. This could make an expatriate assignment to an international joint venture in China a very frustrating experience. Presumably, cross-cultural training may be particularly helpful for the adjustment of Westerners encountering the frustrating work environment in an international joint venture in China. In comparison, the adjustment of Western expatriate executives in other types of organizations may not be facilitated as much by cross-cultural training. In organizational settings totally dominated by the foreign parent as, for example, in a wholly-owned subsidiary, Western expatriates may encounter a less frustrating internal work environment. As presumed, results showed that cross-cultural training had a positive association with work adjustment for expatriates in joint ventures, but there was no relationship with work adjustment for expatriates in other types of organizations in China (Selmer, 2005a).

Cross-Cultural Training Implications

The findings appear to imply that the potential beneficial effects of cross-cultural training on international joint venture expatriates’ work adjustment in China may be enhanced through re-targeting and re-focusing such training. A good idea could be to emphasize the work context in China when training expatriate candidates destined for joint venture operations there. That could be worthwhile also because cross-cultural training aimed at facilitating work adjustment is not very commonly provided to expatriates (Brewster & Pickard, 1994; Early, 1987; Tung, 1982).

Training of Host Nationals

It is known that some multinational corporations use cultural control in their foreign subsidiaries (Edström & Galbraith, 1977). However few academic studies have delved into the phenomenon of organizational acculturation, whereby host country nationals employed in foreign operations become acculturated to the parent organizational culture (Selmer & de Leon, 1996). Since the parent organizational culture typically reflects the parent national culture (Hofstede, 1999), employees in foreign subsidiaries may experience acculturation to a foreign culture within their native country. A number of studies have argued that organizational culture is a mechanism for controlling foreign subsidiaries (Edström & Galbraith, 1977; Jaeger, 1983; Pucik & Katz, 1986). Directly monitoring, reporting and evaluating employee performance is more costly than encouraging employees to share the espoused organizational values in order to guide their behavior (Black, Gregersen, & Mendenhall, 1992). A well-socialized local executive can be expected to act in accordance with the internalized culture (Nicholson, Stepina, & Hochwater, 1990). Some multi-national corporations rely on cultural control to the extent that the national character of the parent organization is exported to its subsidiaries (Kale & Barnes, 1992). In a series of studies of local middle managers employed by foreign subsidiaries in Asia, Selmer & de Leon (1993, 1996, 2002) found empirical evidence for the effects of organizational acculturation. The work values of the local middle managers had changed and become more similar to those of the top expatriate executives and those predominant in the parent country. One possible implication of these findings is that local executives, who are acculturated to the parent cultural values, could oversee operations in much the same manner as an expatriate would have done.

Cross-Cultural Training Implications

It is not known to what extent cultural control is an explicit policy of multi-national corporations, providing a clear mandate for expatriates to influence the work values of local employees, or if organizational acculturation is mainly due to subordinates’ quests for a good working relationship with their foreign bosses (Selmer, 2001a), and the locals incidentally learn new work values from imitation or modelling (Bandura, 1971). Nevertheless, cross-cultural training may be used to make cultural control more effective. A useful technique is values gap analysis, proposed and examined by Selmer in a series of ground-breaking studies (1995, 1996a, 1996b), in which one group estimates the values profile of the other, which is then compared with the actual profile. Based on the findings of such comparisons, local managers could be trained, very much like expatriates (Selmer, 2000), to be aware of the differences and similarities in cultural values, assumptions, communication styles, and attributions between the expatriate top executive’s culture and the local culture to more quickly achieve cultural control effects. Besides, this may also facilitate the adjustment of the expatriate managers, at least in the workplace (Toh & DeNisi, 2007; Vance & Paik, 2005; Vance & Ring, 1994).

Situational Dimensions

Training for Going Home

In a number of studies involving ethnic Chinese expatriating to Chinese-dominated cultures, results suggest that such moves may be fraught with adjustment problems (Selmer, 2002a; Selmer, Ebrahimi, & Li, 2000; Selmer & Ling, 1999; Selmer & Shiu, 1999). For example, studying the adjustment of ethnic Chinese expatriates from Hong Kong assigned to mainland China, it can be concluded that life and work in the mainland is different in many ways from that in Hong Kong. Paradoxically, the common Chinese cultural heritage seems to aggravate the adjustment problems of the Hong Kong expatriates in mainland China instead of facilitating acclimatization. It is remarkable how closely the predicament of many of the expatriates from Hong Kong resembled the worst experiences of expatriate managers in general, as reported in the literature (Black, 1988; Black & Porter, 1991; Lawson & Swain, 1985; Schermerhorn & Bond, 1992; Stening & Hammer, 1992). At work, they generally refrained from adapting their managerial style to local expectations. Instead, they insisted, often in vain, that the subordinates adopt Hong Kong work standards and behaviors, resulting in frustration and in feelings of detachment on the part of the expatriates. Since they often expatriated to mainland China without their families, they could draw little or no support from them. Outside work, they avoided socializing with host nationals, since they usually did not speak the local Chinese dialect. Instead, they lived in the vicinity of and socially interacted with other Hong Kong expatriates with whom they could speak in Cantonese, the local Chinese dialect in Hong Kong. Furthermore, their leisure time was mainly spent in the seclusion of their homes. These findings render further support for the suggestion discussed above, that it could be as difficult for expatriates to adjust to a similar as to a dissimilar host culture.

Cross-Cultural Training Implications

Associated with the literature on repatriation, and especially training for returning expatriates to their original cultural contexts (Andreason & Kinneer, 2005; Lazarova & Caligiuri, 2007; Osman-Gani & Hyder, 2008), even expatriates assigned to other geographical locations, although situated within the same cultural and ethnic sphere, may require cross-cultural training. As proposed above, such training may try to attract expatriates’ attention to the most essential nuances of cultural differences and their behavioral implications in the host culture, as well as attempting to motivate individuals to fine-tune their current thinking and behavior accordingly (Selmer, 2007).

Size of the Host Location and Adjustment

Yet another example of how the effectiveness of cross-cultural training may be influenced by various circumstances at the location of the foreign assignment is to consider the size of the host location in the foreign country. Although many Western expatriates could find their assignment in China frustrating, the magnitude of their frustration and their attained extent of adjustment to life and work could be contingent on the size of their specific host location. Maybe Westerners more easily adjust to large cities with their more Western-style way of life and consumption patterns than in less Westernized small towns and villages. The relevant question to ask is whether Western business expatriates assigned to bigger-sized locations are better adjusted than their counterparts at smaller-sized locations. Investigating Western expatriates assigned to locations of varying size in China, Selmer (2005b) found, as expected, that the size of the location was positively associated with adjustment of the expatriates.

Cross-Cultural Training Implications

Expatriates destined for locations of a smaller size in China could be offered special training in how to cope in that tougher context. Presumably, that may include Chinese language training since the proficiency in English may be higher in larger cities than in small towns (Li, 2002).

Country-Level Dimensions

Adjusting to a Similar Vs. a Dissimilar Culture

Although seldom formally tested, the traditional assumption in the literature on expatriate management is that the greater the cultural novelty of the host country, the more difficult it would be for the expatriate to adjust (Black et al., 1991). In two studies, involving different samples and methodology, this proposition was tested (Selmer, 2006a, 2007). The first study included Western expatriates in China, and although a negative relationship was hypothesized between cultural novelty and adjustment among the respondents, the results showed that there was no significant association between them (Selmer, 2006a). The second study compared the extent of adjustment of American expatriates in Canada and Germany and found that although the Americans perceived Canada as more culturally similar to America than Germany, no significant inter-group differences were detected for any of the measures of adjustment applied (Selmer, 2007). The findings of these two studies support the intuitively paradoxical proposition that it could be as difficult for expatriates to adjust to a similar as to a dissimilar host culture (Carr, Chapter 7 this volume). The suggestion that the degree of cultural similarity/dissimilarity may be irrelevant to how easily expatriates adjust is fundamental and may invoke radical implications, not least for the practice of applying cross-cultural training, which has traditionally been thought to be more necessary the more culturally dissimilar the foreign destination.

Cross-Cultural Training Implications

Considering these findings, cross-cultural training could be useful, not only when assigning expatriates to foreign locations with a very dissimilar culture, but also for assignments to culturally similar host countries. In other words, no matter where expatriates are assigned, they may all benefit from cross-cultural training. However, it may well be that the training should vary with the degree of cultural similarity of the host location (Carr, Chapter 7 this volume). Preparing expatriates destined for very dissimilar cultures may include substantial elements of cognitive training, emphasizing factual information about the host country (Gudykunst, Guzley, & Hammer, 1996). But for expatriates going to countries with a similar culture, it would probably be more important to focus on creating motivation for the individuals to fine-tune their current thinking and behavior. Directing these minute changes, the cross-cultural training may focus on attracting the attention to the most essential nuances of cultural differences and their behavioral implications in the similar host culture (Selmer, 2007; see also, Carr, Chapter 7 this volume).

Conclusions

This chapter used China as a critical test case as an expatriate destination with possible implications for cross-cultural training in general, and in particular for the training of expatriates for other culturally challenging host locations. From the empirical observations and research results of the new dimensions of cross-cultural training discussed above, five major conclusions can be drawn: cross-cultural training works, culture-specific cross-cultural training may be preferable, cross-cultural training could be custom-made, recurring cross-cultural training may be necessary, and everybody may need cross-cultural training.

Cross-Cultural Training Works

Despite some earlier doubts regarding the usefulness of cross-cultural training (Kealey & Protheroe, 1996), recent empirical research on cross-cultural training of expatriates is more unanimous about its benefits (Selmer, 2002d; Waxin, 2004; Waxin & Panaccio, 2005). It may really work if it is carefully implemented, but that also constitutes the problem in a practical situation. The reason that many organizations do not, or only to an insufficient extent, administer cross-cultural training to their expatriates (Brewster, 1995; Hutchings, 2005; Selmer, 2000) may be of a practical nature. There is simply no time for a thorough implementation of cross-cultural training. So, although organizations could be aware of the value of cross-cultural training, they may feel that organizational priorities do not permit cross-cultural training.

Culture-Specific Cross-Cultural Training

Although culture-specific training has become the dominating mode of cross-cultural training, recent empirical evidence has emphasized that past experience from previous foreign assignments may be of limited relevance for being successful in a new posting, especially in another cultural context (Selmer, 2002c; Takeuchi, et al., 2005). If lessons learned in one foreign assignment do not facilitate adjustment in another, cross-cultural training may preferably be culture-specific, and the more specific, the better. Furthermore, that also implies that expatriates could benefit from cross-cultural training for every new foreign assignment they undertake.

Custom-Made Cross Cultural Training

A number of empirical research results discussed above seem to suggest that it could be worthwhile to custom-make cross-cultural training. For example, cross-cultural training intended to facilitate adjusting to a similar culture may require a different type of content than training for a dissimilar culture. Matching personal characteristics with host countries may also require special training for the expatriates teaching them how to exploit this advantage. As has been noted in the repatriation literature, specific training may be required for going home (Andreason & Kinneer, 2005; Lazarova & Caligiuri, 2001; Osman-Gani & Hyder, 2008). However, this may also be the case when someone is expatriated to an identical or very similar ethnical context, but where other societal parameters are quite different. Assignments to tough organizational contexts as well as small-sized host locations may both require custom-made cross-cultural training to facilitate expatriates to deal with these more difficult destinations. Last, but not least, the benefits of some elementary language ability may facilitate the adjustment of expatriates as it could give the impression that they make an effort to understand the local culture (Brislin, 1994; Zimmermann et al., 2003). Besides offering custom-made cross-cultural training to expatriates, specially designed training may also be offered to host national employees at foreign subsidiaries to enhance a desired effect of cultural control.

Recurring Cross-Cultural Training

All these special circumstances at host locations discussed above may also warrant fresh provision of training associated with each and every new assignment, provided it is not a repeated assignment to the same location. However, even in such cases, enough time may have lapsed to justify a refresher course to update expatriates on major developments. In other words, expatriates may still benefit from cross-cultural training, regardless of how many times they have previously been on foreign assignments. This is a radically different proposition compared to the current practice of many international organizations who assign their expatriates to all parts of the world without much cross-cultural training at all (Brewster, 1995; Hutchings, 2005; Selmer, 2000).

Everybody Needs Cross-Cultural Training

The ultimate conclusion of this chapter is that everybody needs cross-cultural training. Training is not only for novices on their first assignment, it could also be beneficial for expatriate veterans with a long and varied career of international assignments. And cross-cultural training is not only for expatriates, since there may be good reasons to also train host country employees. Training of host nationals and expatriates alike is in line with the contention that cross-cultural training will not work unless all sides are equally well-prepared and hence can be treated with cultural respect (Bennett & Bennett, 2004).

Obviously, there could be a multitude of reasons why organizations appear reluctant to embrace the idea of cross-cultural training. This chapter has presented a number of novel justifications for not only introducing cross-cultural training in international organizations, where this concept is little known or applied, but also that it may be worthwhile to expand the scope of cross-cultural training to become a routine preparation associated with every international employee and each instance of mobility. In that way, cultural competence becomes a criterion for all organizations, commercial and non-profit alike, operating on a global scale. Considering the present state of the world economy, when international organizations may cut back on cross-cultural training in their struggle for current survival, they may instead make a fatal mistake for the future. Hopefully, the ideas discussed in this chapter may help avert such unfortunate events.

References

Albert, R. D. (1983). The intercultural sensitizer or culture assimilator: A cognitive approach. In D. Landis, & R. W. Brislin (Eds.), Handbook of intercultural training: Issues in training methodology (Vol. 2, pp. 186–217). New York: Pergamon.

Andreason, A. W., & Kinneer, K. D. (2005). Repatriation adjustment problems and the successful reintegration of expatriates and their families. Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management, 6(2), 109–126.

Aryee, S. (1997). Selection and training of expatriate employees. In N. Anderson & P. Herriot (Eds.), Handbook of selection and appraisal. London: Wiley.

Bandura, A. (1971). Social learning theory. Morristown: General Learning Press.

Bennett, J. M., & Bennett, M. J. (2004). Developing intercultural sensitivity: An integrative approach to global and domestic diversity. In D. Landis, J. M. Bennett, & M. J. Bennett (Eds.), Handbook of intercultural training (3rd ed., pp. 147–165). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Bhawuk, D. P. S., & Brislin, R. W. (2000). Cross-cultural training: A review. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 49(1), 162–191.

Björkman, I., & Lu, Y. (2001). Institutionalization and bargaining power explanations of HRM practices in international joint ventures – The case of Chinese-Western joint ventures. Organization Studies, 22(3), 491–512.

Björkman, I., & Schaap, A. (1994). Outsiders in the middle kingdom: Expatriate managers in Chinese-Western joint ventures. European Management Journal, 12(2), 147–153.

Black, J. S. (1988). Work role transitions: A study of American expatriate managers in Japan. Journal of International Business Studies, 19, 277–294.

Black, J. S., Gregersen, H. B., & Mendenhall, M. E. (1992). Global assignments: Successfully expatriating and repatriating international managers. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Black, J. S., & Mendenhall, M. (1990). Cross-cultural training effectiveness: A review and theoretical framework for future research. Academy of Management Review, 15(1), 113–136.

Black, J. S., Mendenhall, M., & Oddou, G. (1991). Toward a comprehensive model of international adjustment: An integration of multiple theoretical perspectives. Academy of Management Review, 16(2), 291–317.

Black, J. S., & Porter, L. W. (1991). Managerial behaviors and job performance: A successful manager in Los Angeles may not succeed in Hong Kong. Journal of International Business Studies, 22(1), 99–113.

Bloch, B. (1995). Career Enhancement through foreign language skills. International Journal of Career Management, 7(6), 15–26.

Brewster, C. (1995). Effective expatriate training. In J. Selmer (Ed.), Expatriate management: New ideas for international business. Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

Brewster, C., & Pickard, J. (1994). Evaluating expatriate training. International Studies of Management and Organization, 24(3): 18–35.

Brislin, R. W. (1994). Working co-operatively with people from different cultures. In R. Brislin & T. Yoshida (Eds.), Improving intercultural interactions: Modules for cross-cultural training programs. Thousands Oaks: Sage Publications.

Brislin, R. W., Cushner, K., Cherrie, C., & Young, M. (1986). Intercultural interactions: A practical guide. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Brislin, R. W., & Pedersen, P. (1976). Cross-cultural orientation programs. New York: Gardner.

Caligiuri, P. M. (2000). The big five personality characteristics as predictors of expatriate’s desire to terminate the assignment and supervisor-rated performance. Personnel Psychology, 53, 67–88.

Chen, M.-J. (2001). Inside Chinese business: A guide for managers worldwide. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Deshpande, S. P., & Viswesvaran, C. (1992). Is cross-cultural training of expatriate managers effective: A meta analysis. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 16, 295–310.

Dolainski, S. (1997, February). Are expats getting lost in the translation? Workforce, 2, 32–39.

Early, P. C. (1987). Intercultural training for managers: A comparison of documentary and interpersonal methods. Academy of Management Journal, 30(4), 685–698.

Edström, A., & Galbraith, J. (1977). Transfer of managers as a coordination and control strategy in multinational organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 22, 248–263.

Fang, T. (1999). Chinese business negotiating style. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Fantini, A. E. (1995). Introduction – Language, culture and world view: Exploring the nexus. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 19(2), 143–153.

Feely, A. J., & Harzing, A.-W. (2003). Language management in multinational companies. Cross-Cultural Management: An International Journal, 10(2), 37–52.

Fiedler, F. E., Mitchell, T. R. & Triandis, H. C. (1971). The culture assimilator: An approach to cross-cultural training. Journal of Applied Psychology, 55, 95–102.

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1980). An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21, 219–239.

Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Dunkel-Schetter, C., DeLongis, A., & Gruen, R. J. (1986). Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(5), 992–1003.

Gao, G. (1998). `Don’t Take my Word For it’ – Understanding Chinese speaking practices. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 22(2), 163–186.

Gudykunst, W. B., Guzley, R. M., & Hammer, M. R. (1996). Designing intercultural training. In D. Landis & R. S. Bahgat (Eds.), Handbook of intercultural training (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Hambrick, D. C., Li, J. T., Xin, K., & Tsui, A. S. (2001). Compositional gaps and downward spirals in international joint venture groups. Strategic Management Journal, 22, 1033–1053.

Hayet, M. (2000). New concepts in corporate language training. Journal of Language for International Business, 11(1), 57–81.

Hofstede, G. (1999). Problems remain, but theories will change: The universal and the specific in 21st-century global management. Organizational Dynamics, 2, 34–44.

Hutchings, K. (2005). Koalas in the land of pandas: Reviewing Australian expatriates’ China preparation. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16(4), 553–566.

Jaeger, A. M. (1983). The transfer of organizational culture overseas: An approach to control in the multinational corporation. Journal of International Business Studies, 15, 91–114.

Kale, S. H., & Barnes, J. W. (1992). Understanding the domain of cross-national buyer–seller interactions. Journal of International Business Studies, 23(1), 101–132.

Kaye, M., & Taylor, W. G. K. (1997). Expatriate culture shock in China: A study in the beijing hotel industry. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 12(8), 496–510.

Kealey, D. J., & Protheroe, D. R. (1996). The effectiveness of cross-cultural training for expatriates: An assessment of the literature on the issue. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 20(2), 141–165.

Kraemer, A. (1973). Development of a cultural self-awareness approach to instruction in intercultural communication. Technical Report No. 73-17. Arlington: HumRRO.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer.

Lawson, K. S., & Swain, P. A. (1985). Leadership style: Differences between expatriates and locals. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 6(4), 8–11.

Lazarova, M., & Caligiuri, P. (2001). Retaining repatriates: The role of organization support practices. Journal of World Business, 36(4), 389–401.

Leong, F. T. L., & Kim, H. H. W. (1991). Going beyond cultural sensitivity on the road to multiculturalism: Using the intercultural sensitizer as a counselor training tool. Journal of Counseling and Development, 70, 112–118.

Li, J. T., Xin, K., & Pillutla, M. (2002). Multi-cultural leadership teams and organizational identification in international joint ventures. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(2), 320–337.

Li, X. (2002). A nation hot for English. China Today, 5, 23–33.

Liu, D. (1995). Sociocultural transfer and its effect on second language speakers’ communication. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 19(2), 253–265.

Lowe, S. (2003). Chinese culture and management theory. In I. Alon (Ed.), Chinese culture, organizational behavior, and international business management. Westport: Praeger.

Mamman, A., & Richards, D. (1996). Perceptions and possibilities of intercultural adjustment: Some neglected characteristics of expatriates. International Business Review, 5(3), 283–301.

Mendenhall, M. E., Stahl, G. K., Ehnert, I., Oddou, G., Osland, J. S., & Kühlmann, T. S. (2004). Evaluation studies of cross-cultural training programs: A review of the literature from 1988 to 2000. In D. Landis, J. M. Bennett, & M. J. Bennett (Eds.), Handbook of intercultural training (3rd ed., pp. 129–144). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Nicholson, J. D., Stepina, L. P., & Hochwater, W. (1990). Psychological aspects of expatriate effectiveness. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 2, 127–145

Osman-Gani, A. M., & Hyder, A. S. (2008). Repatriation readjustment of international managers: An empirical analysis of HRD interventions. Career Development International, 13(5), 456–475.

Pearlin, L. I., & Schooler, C. (1978). The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 19, 2–21.

Pucik, V., & Katz, J. H. (1986). Information, control, and human resource management in multinational firms. Human Resource Management, 25, 121–132.

Schermerhorn, J. R., Jr., & Bond, M. H. (1992). Upward and downward influence tactics in managerial networks: A comparative study of Hong Kong Chinese and Americans. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 8(2), 147–158.

Scheu-Lottgen, D. U., & Hernandez-Campoy, J. M. (1998). An analysis of sociocultural miscommunication: English, Spanish and German. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 22(4), 375–394.

Selmer, J. (1995). How familiar are expatriate managers with their subordinates’ work values? The case of Singapore. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 2(1), 8–16.

Selmer, J. (1996a). What do expatriate managers know about their HCN subordinates’ work values: Swedish executives in Hong Kong. Journal of Transnational Management Development, 2(3), 5–20.

Selmer, J. (1996b). What expatriate managers know about the work values of their subordinates: Swedish executives in Thailand. Management International Review, 36(3), 231–243.

Selmer, J. (1999a). Effects of coping strategies on Sociocultural and psychological adjustment of Western expatriate managers in the PRC. Journal of World Business, 34(1), 41–51.

Selmer, J. (1999b). Western business expatriates’ coping strategies in Hong Kong vs. the Chinese mainland. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 37(2), 92–105.

Selmer, J. (2000). A quantitative needs assessment technique for cross-cultural work adjustment training. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 11(3), 269–281.

Selmer, J. (2001a). Antecedents of expatriate/local relationships: Pre-knowledge vs. Socialization tactics. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 12(6), 916–925.

Selmer, J. (2001b). Coping and adjustment of Western expatriate managers in Hong Kong. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 17(2), 167–185.

Selmer, J. (2002a). The Chinese connection? Adjustment of Western vs. Overseas Chinese expatriate managers in China. Journal of Business Research, 55(1), 41–50.

Selmer, J. (2002b). Coping strategies applied by Western vs. Overseas Chinese business expatriates in China. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(1), 19–34

Selmer, J. (2002c). Practice makes perfect? International experience and expatriate adjustment. Management International Review, 42(1), 71–87.

Selmer, J. (2002d). To train or not to train? European expatriate managers in China. International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management, 2(1), 37–51.

Selmer, J. (2004). Psychological barriers to adjustment of Western business expatriates in China: Newcomers vs. long stayers. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 15(4&5), 794–813.

Selmer, J. (2005a). Cross-cultural training and expatriate adjustment in China: Western joint venture managers. Personnel Review, 34(1), 68–84.

Selmer, J. (2005b). Is bigger better? Size of the location and adjustment of business expatriates in China. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16(7), 1228–1242.

Selmer, J. (2006a). Cultural novelty and adjustment: Western business expatriates in China. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(7), 1209–1222.

Selmer, J. (2006b). Language ability and adjustment: Western expatriates in China. Thunderbird International Business Review, 48(3), 347–368.

Selmer, J. (2007). Which is easier? Adjusting to a similar or to a dissimilar culture: American business expatriates in Canada and Germany. International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management, 7(2), 185–201.

Selmer, J., & de Leon, C. T. (1993). Organizational acculturation in foreign subsidiaries. The International Executive, 35(4), 321–338.

Selmer, J., & de Leon, C. T. (1996). Parent cultural control through organizational acculturation: Local managers learning New Work values in foreign subsidiaries. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 17, 557–572.

Selmer, J., & de Leon, C. T. (2002). Parent cultural control of foreign subsidiaries through organizational acculturation: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(8), 1147–1165.

Selmer, J., Ebrahimi, B. P., & Li, M. T. (2000). Adjustment of Chinese mainland vs. Western business expatriates assigned to Hong Kong. International Journal of Manpower, 21(7), 553–565.

Selmer, J., Lauring, J., & Feng, Y. (2009). Age and expatriate job performance in greater China. Cross Cultural Management – An International Journal, 16(2), 131–148.

Selmer, J., & Leung, A. (2003). International adjustment of female vs. male business expatriates. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 14(7), 1117–1131.

Selmer, J., & Leung, A. (2007). Symptom and problem focussed coping strategies of women business expatriates and their socio-cultural adjustment in Hong Kong. Women in Management Review, 22(7), 588–605.

Selmer, J., & Ling, E. S. H. (1999). Adjustment of mainland PRC business managers assigned to Hong Kong. Journal of Asian Business, 15(3), 27–40.

Selmer, J., & Shiu, S. C. (1999). Coming home? Adjustment of Hong Kong Chinese expatriate business managers assigned to the People’s Republic of China. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 23(3), 447–465.

Sergeant, A., & Frenkel, S. (1998). Managing people in China: Perceptions of expatriate managers. Journal of World Business, 33(1), 17–34.

Stening, B. W., & Hammer, M. R. (1992). Cultural baggage and the adaptation of expatriate American and Japanese managers. Management International Review, 32(1), 77–89.

Takeuchi, R., Tesluk, P. E., Yun, S., & Lepak, D. P. (2005). An integrative view of international experience. Academy of Management Journal, 48(1), 85–100.

Toh, S. M., & DeNisi, A. S. (2007). Host country nationals as socializing agents: A social identity approach. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 28, 281–301.

Tung, R. L. (1981). Selection and Training of Personnel for Overseas Assignments, Columbia Journal of World Business, 16, 68–78.

Tung, R. L. (1982). Selection and training procedures of US, European and Japanese multinationals. California Management Review, 25(1): 57–71.

Vance, C. M., & Paik, Y. (2005). Forms of host-country national learning for enhanced MNC absorptive capacity. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 20(7), 590–606.

Vance, C. M., & Ring, S. M. (1994). Preparing the host country work force for expatriate managers: The neglected other side of the coin, Human Resource Development Quarterly, 5(4), 337–352.

Wang, Z. M. (2000). Management in China. In M. Warner (Ed.), Regional encyclopedia of business & management: Management in Asia Pacific. London: Thomson Learning.

Waxin, M.-F. (2004). The impact on country of origin on expatriates’ interaction adjustment. International Journal if Intercultural Relations, 28(1), 61–79.

Waxin, M.-F., & Panaccio, A. (2005). Cross-cultural training to facilitate expatriate adjustment: It works! Personnel Review, 34(1), 51–67.

Weber, G. (2004). English rules. Workforce Management, 5, 47–50.

Zimmermann, A., Holman, D., & Sparrow, P. (2003). Unraveling adjustment mechanisms: Adjustment of German expatriates to intercultural interactions, work, living conditions in the People’s Republic of China. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 3(1), 45–66.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2010 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Selmer, J. (2010). Global Mobility and Cross-Cultural Training. In: Carr, S. (eds) The Psychology of Global Mobility. International and Cultural Psychology. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-6208-9_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-6208-9_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4419-6207-2

Online ISBN: 978-1-4419-6208-9

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)