Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review focuses on one state’s multidisciplinary legislative efforts to decrease the incidence of child maltreatment, including fatalities and near-fatalities. Such efforts have encompassed primary and secondary prevention modalities, including early support to parents, training, and education about recognition and reporting of child maltreatment for professionals who interact with children, review of all child deaths, and multidisciplinary in-depth case review of the most serious child maltreatment cases.

Recent Findings

Although reliable trends can be difficult to determine based upon the complexity of the problem and multiple confounding variables, there are a number of indicators that suggest these cumulative efforts are beginning to have a favorable impact on the most serious child maltreatment cases, although heightened awareness has likely contributed to an increase in the total number of reported cases.

Summary

Multidisciplinary collaborative efforts including governmental, academic, and non-profit entities may affect meaningful change in legislation and other interventions to decrease the incidence of the most serious cases of child maltreatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) define child maltreatment as “any act or series of acts of commission or omission by a parent or other caregiver (e.g., clergy, coach, and teacher) that results in harm, potential for harm, or threat of harm to a child” [1]. Although the definition of child maltreatment varies to some degree by the agency that is reporting it, each state has definitions of child maltreatment within its civil and criminal statutes. Most states recognize four types of child maltreatment: neglect, physical abuse (also known as non-accidental trauma), sexual abuse, and emotional injury. Recently, Kentucky has codified the recognition that the commercial sexual exploitation of children (also known as human trafficking) is a fifth form of abuse that mandates reporting as well as services for victims, rather than criminalization of the unlawful sexual transactions [2]. Federal legislation provides guidance to states by identifying a minimum set of acts or behaviors that define child maltreatment. The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA), (42 U.S.C. 5101), as amended by the CAPTA Reauthorization Act of 2010 (P.L. 111–320), defines child abuse and neglect as: “At a minimum, any recent act or failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker which results in death, serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse or exploitation, or an act or failure to act, which presents an imminent risk of serious harm” [3]. Under this definition, a “child” is any person who is younger than 18 years of age and not an emancipated minor.

The factors that contribute to child maltreatment are multidimensional and incompletely understood. Multiple disciplines have contributed to our current understanding, including criminal justice, social work, psychology, medicine, and public health/epidemiology. Characteristics of the parent/caregiver, the child victim, the family dynamic, and community and environment all play important roles in determining risk. When considering risk, it is critical to understand that child maltreatment spans all cultural, socioeconomic, and geographical categories [4]. Table 1 lists some of the well-established risk factors for maltreatment. While victims usually come from families with a combination of risk factors, there is no single factor that predicts child maltreatment. While the majority of abusers are male, both men and women can commit child maltreatment. Someone known and trusted by the child’s family is usually the abuser.

Scope of the Problem

Child maltreatment is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the pediatric population. The incidence of child abuse and neglect has been extensively studied and is reported annually by the United States Department of Health and Human Services. In federal fiscal year 2014, there were a nationally estimated 702,000 victims of child abuse and neglect, resulting in a rate of 9.4 victims per 1000 American children [5]. The effects of child maltreatment are serious, and a child fatality is the most tragic consequence. During 2014, a nationally estimated 1580 children died from abuse and neglect at a rate of 2.13 deaths per 100,000 children in the population [5]. Abusive head trauma is the most common cause of brain injury death in infants under 1 year of age [6]. Pediatric abusive head trauma (formerly known as shaken baby syndrome) is defined as an injury to the skull or intracranial contents of an infant or young child (<5 years of age) due to inflicted blunt impact and/or violent shaking [7]. In addition to the direct harm to children, their families, and their communities, there is also a staggering financial cost. A CDC report estimated that the total lifetime economic burden resulting from 1 year of new cases of fatal and non-fatal child maltreatment in the USA is approximately $124 billion (i.e., 1 year’s worth of new cases, spread out over the lifetimes of the children, and including not only medical bills, but lost productivity, mental health, crime, and other consequences) [8].

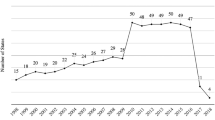

Child maltreatment is a significant problem in Kentucky. Our state consistently ranks among the nation’s highest in terms of rates of victimization and mortality. In 2007, Kentucky had the highest rate of child deaths from abuse and neglect in the USA [9, 10]. This disturbing fact precipitated a statewide call to action. Since 2007, there has been some variability but an overall reduction in the number of fatalities in Kentucky, although the change is not yet statistically significant. In 2014, our official fatality rate dropped below the national average; however, the incidence of child maltreatment continued to be among the highest in the country (Fig. 1). The fatality rate rose slightly in 2015, and both state reports and media accounts reflected growing concern regarding an increased incidence of non-fatal maltreatment and an overwhelmed Department of Community Based Services [11, 12].

Comparison of annual child maltreatment fatality rates (a) and victimization rates (b) between Kentucky and the USA. Data from United States Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau annual Child Maltreatment reports

Prevention

Child maltreatment is a multifaceted problem often rooted in unrealistic developmental expectations of children, family, and community violence, substance abuse, and undiagnosed or untreated mental illness. Adverse child experiences (ACEs) such as child abuse are now a widely recognized group of exposures that have direct, linear relationships to a number of adverse outcomes in adults [13]. For example, those individuals maltreated as children have a 30% higher likelihood of committing a violent crime in adulthood. The complexity of factors leading to child maltreatment makes preventing child abuse an equally complex challenge. Primary prevention strategies are aimed at creating safe, stable, nurturing relationships through increased social support, education, community resources, and access to medical and mental health care for new parents, an approach endorsed by the Centers for Disease Control [14••, 15••]. Secondary prevention targets programs to at-risk populations such as school age children at risk for sexual abuse [16]. Tertiary prevention strategies (also known as mitigation) are directed at protecting and healing children and families after maltreatment has occurred [16]. Mitigation is particularly critical because an abused child has a 50% chance of being abused again and has a significant risk of dying from abuse if the abuse continues [17, 18]. It is very rare for children to die or to be permanently disabled the first time they are abused, making early detection paramount not only to preventing future abuse but also to saving children’s lives.

National Policy Initiatives to Address Child Abuse

The 2013 Institute of Medicine report New Directions in Child Abuse and Neglect Research points to the contributions to policy analysis that can come from variation in state law addressing child abuse and neglect [19••]. Because states have enacted different types of laws with the same objectives, comparing them might help policy makers distinguish between effective and ineffective approaches. However, the literature in this area remains scant [20••, 21] in contrast to the extensive body of research evaluating programs to address specific aspects of child maltreatment [22] and cataloging state law [23]. This research is challenging due to the countless, complex confounding factors when attempting to determine the effect of new legislation on a multifactorial and highly complex condition such as child maltreatment.

The public health approach to preventing child maltreatment includes policy initiatives intended to affect social determinants of health [22]. By improving access to needed services, including safe living environments and interventions to reduce parental stress, state policy has the potential to reduce well documented risk factors for child maltreatment. Examples include home visitation programs for parents of young infants, which were the subject of legislation in more than 20 states between 2008 and 2015, use of federal funds to help young parents earn GEDs and receive vocational training, and programs to increase the rate of high school graduation [24]. Most of the home visitation programs were universally available to new parents, regardless of risk. Many are now being expanded—including in Kentucky—to include multiparous women with infants less than 3 months. In Kentucky, one particularly effective and evidence-based approach to parenting education and support is the Health Access Nurturing Development Services (HANDS) program, funded through state and federal funds. HANDS is a free, voluntary, home-visiting program for pregnant women and new parents that supports all areas of a baby’s development through the first 2 years of a baby’s life. Outcomes have been shown to be highly effective at preventing child maltreatment, and HANDS highlights an excellent example of a primary prevention program [25].

Another example of policy to address social determinants of child maltreatment is earned income credits against state income tax obligations, which are available to low-income households in 26 states and the District of Columbia and have the potential to reduce the financial stress that raises the risk of child maltreatment.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) endorses these types of policy strategies as part of its THRIVES approach [26] under the rubrics of “training in parenting” and “surveillance and evaluation”. However, Gilmer et al. [27], among many others, caution that a single approach to parent education is unlikely to be effective given the wide variation in learning styles and the volume of information presented to new parents. In most states, however, the parental education mandate is applied post facto, to those who have already harmed children, or placed them at risk for harm [28].

Some state legislative initiatives include the identification of a specific funding stream, such as tax return check-offs, tobacco settlement proceeds, or incremental fines and fees [22]. At the federal level, Title II of the 1974 Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) [3] provides some funding for community agencies to provide support for families at risk. Another federal funding source is the Social Services Block Grant, which allows states to tailor funded programs to meet identified needs specific to their populations. However, the myriad demands on such funds typically lead to shortfalls in program capacity and ongoing unmet need.

Kentucky Unified Juvenile Code and Mandatory Reporting

The Kentucky Unified Juvenile Code [28], found at KRS Chapters 600 to 645, includes the declaration of a child’s right to be free from maltreatment. The code provides the legal definitions of neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and dependency. KRS 620.030, enacted in 1987, requires any person with a reasonable suspicion that a child is being maltreated to report to child protective services or other approved entity. In 2013, the statute was amended to include mandatory reporting for suspected child victims of human trafficking. This provision mandates reporting of child maltreatment whether it occurs in the home, the school, or other community settings. Furthermore, the code requires that these reports be assessed and investigated and requires that social services be provided to children found to be experiencing maltreatment.

Penalties for willful failure to report begin at the misdemeanor level for first instances and escalate to felony levels for subsequent offenses. This requirement puts Kentucky among a substantial minority of states, currently numbering 18, with universal reporting requirements [24]. Universal in this case is defined at all PEOPLE, regardless of professional status or occupation and in any concerning circumstance.

Community Education as a Legislative Focus in Kentucky

Between 2010 and 2015, a series of comprehensive legislative initiatives were successfully enacted, which directly address recognition of early signs of abuse for a wide variety of professionals who come into contact with children. The various bills target almost all adult professionals who routinely encounter children, creating one of the most comprehensive statewide mandatory training requirements in the nation. The initial 2010 bill (HB 285) required education for foster parents, law enforcement, childcare providers, health care providers, first responders, social workers, and others [29]. Subsequent bills were passed requiring training for physicians (2013, HB 157) and educators (2015, SB 119). The focus of all of the trainings is tailored to the specific audience, with an emphasis on factors that make certain children at higher risk, factors that make caregivers at higher risk, specific characteristics of caregiver-child dynamics, and signs/symptoms of abusive head trauma (AHT). Examples of signs/symptoms discussed include bruising patterns in children, vomiting in the absence of diarrhea, new onset seizure, rapid increase in head circumference, and BRUE (brief resolved unexplained event) (formerly known as ALTE or apparent life-threatening event) [30]. In addition, learners are taught about the need for immediate medical evaluation of any bruise on a non-mobile infant, tips on how to make a thorough and effective report to authorities, and documentation issues. Each educational program includes information about prevention and the building of resilience and protective factors in children and their families.

As an example of implementation of these educational requirements, KRS 311A.120 and KRS 311A.127 mandates an educational course and continuing education for all emergency medical providers including first responders by the Kentucky Board of Emergency Medical Services (KBEMS). This includes the completion of one and one-half (1.5) hours of board approved continuing education covering the recognition and prevention of pediatric abusive head trauma, as defined in KRS 620.020, at least one (1) time every five (5) years. The required one and one-half (1.5) hours is included in the current number of required continuing education hours. The course, developed by an academic child abuse pediatrician with major input from the Prevent Child Abuse Kentucky and other state representation and implemented in 2012, had reached the entire EMS workforce in Kentucky within the 3-year mandate. The HRSA Kentucky Emergency Medical Services for Children Program (KYEMSC) has taken a lead role in developing program support to supply this required education including provision of the Train-the-trainer programs for EMS Educators and program updates for previously approved instructors.

Statewide Identification and Review of Fatal and Near-Fatal Child Abuse

Work has been ongoing for several years in Kentucky to develop a workable surveillance system that would neither miss true cases nor overinflate their numbers. There seemed to be some concern that our hospital billing data might be seriously flawed, given the low numbers we were finding when applying case definitions for AHT and child maltreatment to those data sets. The approach was to take nationally standard or suggested case definitions for which there were published results (rates) available, apply those definitions to our KY hospital data, and compare the rates [31,32,33]. We found that rates utilizing our current system were reasonably congruent with the other national models. However, it still may be the case that hospital-billing data everywhere has limitations for child abuse surveillance (i.e., we may all be undercounting child maltreatment encounters by using billing data). One system for categorizing child neglect that included the presence of smoking as a marker was tried; in that case the data was overwhelmed with cases that did not truly measure abuse/neglect as we were looking to define it, and that model was not workable in a tobacco growing state with high rates of smoking (personal communication Michael Singleton). Work to develop the data that feeds into a surveillance system, and to improve the quality of that data, has been occurring through child fatality review.

Child Fatality Review to Inform Scope of the Problem and Focus Prevention Efforts

Child fatality review (CFR) or child death review (CDR) is the multi-agency, multi-disciplinary review of all child deaths under age 18. Accurate determination of the cause and manner of death, including consideration of any factors that might make prevention of a similar future death possible, create the data that informs prevention efforts. While CDR has wisely come to be seen as a public health tool utilized for the analysis of deaths from all causes, its American roots lie strongly in the area of child abuse identification and prevention.

The historic first multi-agency, multi-disciplinary child death review team was formed in 1978 after review of a child abuse death in Los Angeles, California revealed that the child had contact with multiple agencies prior to her death, none of which were aware of the others [34, 35]. As CDR has spread across the USA and eventually to other countries, there has been a concomitant shift to consideration of the preventable factors in all deaths, since such things as immunizations, access to care, and preventive measures for unintentional injuries and prematurity are also clearly a part of the prevention of child deaths. Child death review also serves as a quality improvement tool to address the on-going need to improve child death scene investigation [36]. An additional compelling reason that CDR and thorough investigation and review of all child deaths is important to child abuse surveillance and prevention is the fact that more than half of children who die of abuse were not previously known to the child protection system and may not immediately have been identified as abused. Thus, reviewing only known child abuse deaths might result in missing almost half the cases of actual fatal abuse.

In Kentucky, child fatality review began in 1995 with a multidisciplinary, multi-agency legislative workgroup mirroring the ideal composition of a review team, whose goal was to establish legislation for the process of review of all pediatric deaths. Legislation passed and went into effect in 1996. This early legislation only mandated data collection and a yearly report to the legislature from the state Department for Public Health and monthly notifications from the county Coroner’s to the state Department for Public Health and 3 local county entities (law enforcement, social services, and the local health department); it allowed but did not mandate a state team and local county teams. State team efforts since have supported the formation and education of county teams as well as the development of a number of recommendations for prevention of prematurity, injury and violence, but have been significantly impacted by lack of funding. In a state with a mixed medical examiner/coroner system in which coroners are elected every 4 years, the result is that about half the counties has an active team at any given time. Nevertheless, over the years, this CFR process has yielded unexpected abuse findings in cases of sudden death in infants, several drowning cases, and from intentionally set fires. In other words, the public health CFR teams at the county level are needed to identify the 50% of children that would not otherwise be found.

Currently, the Kentucky Child Fatality and Near Fatality Panel (http://www.lrc.ky.gov/lrcpubs/RR422.pdf), formed in 2013 and codified in legislation in 2014, is composed of members representing numerous disciplines. Panel members include representatives of the judiciary, law enforcement, prosecutors, forensic pathology, child abuse pediatrics, public heath, epidemiology, substance abuse, and domestic violence counseling, mental health, community non-profits, and others. Any child who dies or meets the federal definition of near-fatality who was reported to the Child Protective Services is reviewed, in addition to any additional cases for which concerns are raised by either the local county level child fatality review teams or at the state public health level that supports those teams. In addition, a separate public health-based task force (the Sudden Unidentified Infant Death (SUID) case review panel) reviews known infant deaths (identified by death certificates) and determines if there is sufficient cause to send the case to the panel for full review. Once the panel members review a case, missed opportunities are identified by system (i.e., birth hospitalization, medical, child protective services, schools/daycares, court, etc.). From the missed opportunities, recommendations are developed for the annual report, which is presented to the legislature and released to the public. The panel may also choose to send respectful, anonymous feedback to various entities regarding any identified missed opportunities.

As cases are reviewed, data is collected about risk factors, potential missed opportunities to protect the child, and any recommendations that might help prevent similar events in the future. Data is then analyzed and reported with assistance from epidemiologists from state public health.

Child Abuse Pediatrics as a Specialty

The discipline of child abuse pediatrics, with its first certification exam in 2009, is a relatively young subspecialty. As such, its role in children’s hospitals, child advocacy centers, and academic medical centers is still evolving. Unfortunately, the demand for this new specialty surpasses the supply. Child abuse pediatricians help guide the medical providers regarding the appropriate testing to identify occult injuries and to assess for underlying medical conditions. They also help interpret medical findings for investigators so that CPS and law enforcement understand the injuries and what might have caused them. Because legal testimony is a standard part of a child abuse pediatrician’s practice, they often free other providers from the obligations of the courtroom. While all of these responsibilities might limit their ability to independently conduct meaningful research, partnership with other disciplines can allow for robust projects that can guide prevention efforts at the individual, family, and community level.

Opportunities

Social factors, including the high rate of poverty in young families and lack of adequate social services, elevate the risk of child maltreatment. Despite the nominal requirement for mental health coverage parity with physical health insurance coverage, young families struggle to find adequate services and resources. Policy initiatives that provide education and support for parents by helping them cope with stressors, choose safe caregivers, and understand realistic expectations for children, as well as policies that will help parents meet their basic needs of housing, food, and safety, and promote safe, stable, and nurturing relationships will help prevent child abuse. In addition, policy initiatives must also help the state, non-profit organizations, and communities improve the ability of health, social services, and other community professionals to support all families.

Conclusions

Increasing statewide awareness of child maltreatment has led to policy initiatives that address recognition, reporting, and mitigation of the causes and consequences of abuse. State legislation and related health policy initiatives have enhanced reporting requirements and improved access to services and quality of assessments. Complementing policy initiatives and programs for low-income families can help to mitigate the multiple stress factors contributing to abuse, and the discipline of child abuse pediatrics has increased expertise in the field and improved the medical assessments of injured children. Multi-sector collaborative efforts including governmental, academic, and non-profit entities such as those undertaken in Kentucky can promote changes in legislation and other policy interventions to decrease the incidence of the most serious cases of child maltreatment. In Kentucky, heightened awareness has also likely contributed to increased reporting and an overall increase in the number of cases annually. Therefore, additional research into the effectiveness of these initiatives for the prevention of abuse is sorely needed to decrease morbidity and mortality among our nation’s children.

While the introduction of new training mandates is nearly always met with resistance from professional organizations, making the case for child safety and prevention of child abuse fatalities has been successful. As with any new legislation, is has been helpful to build foundational knowledge with the legislature, speak with various stakeholder to understand any reservations or concerns, and to address potential barriers before drafting language. One of the most important lessons learned is that a coalition of stakeholders who address a legislature as one body is far more effective than any single individual or group. The additional benefit of working together across disciplines is that when one group or individual becomes discouraged, there is inevitably another that will step up and keep the momentum going. Although many of these legislative initiatives took years to finally enact, the perseverance on behalf of children is beginning to pay off.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childmaltreatment/definitions.html.

Human Trafficking Victims Rights Act. 2013 Ky. Acts 25, available at http://www.lrc.ky.gov/record/13rs/HB3.html.

The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act Including Adoption Opportunities & The Abandoned Infants Assistance Act as Amended by P.L. 111–320 The CAPTA Reauthorization Act of 2010. Available from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/capta2010.pdf.

Jenny CC, Hymel KP, Ritzen A, Reinert SE, Hay TC. Analysis of missed cases of abusive head trauma. JAMA. 1999;281(7):621–6.

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. Child Maltreatment. 2014. Available from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment.

Keenan HT, Runyan DK, Marshall SW, Nocera MA, Merten DF. A population-based comparison of clinical and outcome characteristics of young children with serious inflicted and noninflicted traumatic brain injury. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):633–9. doi:10.1542/peds.2003-1020-L.

Park SE, Annest JL, Hill HA, Karch DL. Pediatric abusive head trauma: recommended definitions for public health surveillance and research. 2012 Centers for Disease Control. www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/pdf/PedHeadTrauma-a.pdf.

Fang X, Brown DS, Florence CS, Mercy JA. The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States and implications for prevention. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36:156–65.

We can do better: child abuse deaths in America. (2009 report) Every Child Matters Education Fund. Available from http://socialworkers.org/protectchildren/wcdbv2.pdf

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. Child maltreatment. 2007. Available from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment.

Child Fatality and Near Fatality External Review Panel. 2016 Annual Report. Available from http://justice.ky.gov/Pages/CFNFERP.aspx.

Cheves J. Child abuse and neglect up 55 percent in Kentucky since 2012. Lexington Herald Leader. 2017. http://www.kentucky.com.news/politics-government/article130535059.html.

Felitti V, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–58.

•• Thornberry TP, Henry KL, Smith CA, Ireland TO, Greenman SJ, Lee RD. Breaking the cycle of maltreatment: the role of safe, stable, and nurturing relationships. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(4 Suppl):S25–31. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.04.019. This article highlights a national primary prevention strategy that reinforces protective factors while addressing many of the underlying caregiver-child issues that contribute to child maltreatment.

•• Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing Maltreatment by Promotion of Safe Stable and Nurturing Relationships between Children and Caregivers. Strategic Direction for Child Maltreatment Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/cm_strategic_direction--long-a.pdf. Endorses primary prevention strategies aimed at creating safe, stable, nurturing relationships.

MacMillian HL, Wathen CN, Barlow J, Fergusson DM, Leventhal JM, Taussig HN. Child maltreatment 3 interventions to prevent child maltreatment and associated impairment. Lancet. 2009;373:250–66.

Saade DN, Simon HK, Greenwald M. Abused children: missed opportunities for recognition in the ED. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:524.

McDonald KC. Child abuse: approach and management. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75:221–8.

•• Petersen A, Joseph J, Feit M, editors. New directions in child abuse and neglect research. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2013. The most comprehensive recent statement that indicates where research and evidence is needed concerning the topic of child abuse.

•• Krugman RD. Pediatric research and child maltreatment: where have all the flowers gone? Ped Research. 2016;71(1):236–7. Child Abuse Pediatrics is a new subspecialty with no specific NIH funding stream.

Seppes RD. Child abuse research 2015: It’s time for breakthrough. Ped Research. 2016;71(1):234–5.

Henrickson H, Blackman K. State policies addressing child abuse and neglect. National Conference of State Legislatures. 2015. Online at http://www.ncsl.org/Portals/1/Documents/Health/StatePolicies_ChildAbuse.pdf

Children’s Bureau, U.S. Dept. of Health & Human Services. Mandatory reporters of child abuse and neglect. Online at https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/systemwide/laws-policies/statutes/manda/

Williams CM, Asaolu I, Robl J, Jewell T. Child health improvement by HANDS home visiting program (unpublished manuscript). 2014. University of Kentucky Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Lexington, KY.

Hillis S, Mercy J, Saul J, Gleckel J, Abad N, Kress H. THRIVES: using the best evidence to prevent violence against children. J Public Health Policy. 2016;37(S1):S51–65.

Gilmer C, Buchan JL, Letourneau N, Bennett CT, Shanker SF, Fenwick A, Smith-Chant B. Parent education interventions designed to support the transition to parenthood: a realist review. Int J Nursing Studies. 2016;29:118–33.

Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services (CHFS), Reporting Child Abuse and Neglect, available online at http://chfs.ky.gov/NR/rdonlyres/0984FD14-A494-4055-9C10-98CDD433F8C9/0/ChildAbuseandNeglectBooklet.pdf.

Kentucky 2010 House Bill 285, online at http://www.lrc.ky.gov/record/10rs/HB285.htm.

Pierce MC, Kaczor K, Aldridge S, O’Flynn J, Lorenz D. Bruising characteristics discriminating physical child abuse from accidental trauma. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):6774.

Tieder JS, Bonkowsky JL, Etzel RA, Franklin WH, Gremse DA, Herman B, Katz ES, Krilov LR, Merritt II JL, Norlin C, Percelay J, Sapién RE, Shiffman RN, Smith MBH, for the SUBCOMMITTEE ON APPARENT LIFE THREATENING EVENTS. Brief resolved unexplained events (formerly apparent life-threatening events) and evaluation of lower-risk infants. Pediatrics 2016; 137:e20160590. doi.10.1542/peds.2016-0590

Leventhal JM, Martin KD, Gaither JR. Using US data to estimate the incidence of serious physical abuse in children. Pediatrics. 2012a;129:458–64.

Leventhal JM, Gaither JR. Incidence of serious injuries due to physical abuse in the United States: 1997 to 2009. Pediatrics. 2012b;130:847–52.

Shanahan ME, Zolotor AJ, Parrish JW, Barr RG, Runyan DK. National, regional and state abusive head trauma: application of the CDC algorithm. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e1546–33.

Durfee MJ, Gellert GA. Origins and clinical relevance of child death review teams. JAMA. 1992;267(23):3172–5.

Durfee M, Tilton-Durfee D. Multiagency child death review teams: experience in the United States. Child Abuse Rev. 2014;4:377–81.

Fraser J, Sidebotham P, Frederick J, Covington T, Mitchell EA. Learning from child death review in the USA, England, Australia, and New Zealand. Lancet. 2014;364:894–903.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Drs. Draus, Costich, Pollack, Currie, and Fallat declare no conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Injury Prevention

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Draus, J.M., Costich, J., Pollack, S.H. et al. Injury Prevention and State Law as Strategies for the Reduction of Child Maltreatment Fatalities. Curr Trauma Rep 3, 89–96 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40719-017-0080-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40719-017-0080-4