Abstract

Purposes of review

In order to introduce the advances and use of the new sub-section addressed to the drug hypersensitivity reactions (DHRs) in the World Health Organizations’ International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-11 revision, we here proposed a used case document and discuss the perspective of this new framework.

Recent findings

We expect that the construction of the new section addressed to DHRs in the ICD-11 will allow the collection of more accurate epidemiological data to support quality management of patients with drug allergies, and better facilitate health care planning to implement public health measures to prevent and reduce the morbidity and mortality attributable to DHRs.

Summary

Allergy and hypersensitivity reactions, including DHRs, have never been well classified in the World Health Organization’s (WHO) ICD. The ALLERGY in ICD-11 initiative was launched 6 years ago to have a better representation of these disorders in the ongoing 11th revision of the ICD. It has been supported by six major international allergy academies, and collaboration with the WHO has been established and is ongoing so far. This document intends to present advances and use of the new “Drug hypersensitivity” section of the ICD-11.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why do we need to classify and code drug hypersensitivities?

Assessment and models of health have been constructed around the medical classification “language” to better understand heath-disease balance and outcomes as well as to support evidence-based decision-making. It has created the need for mechanisms and tools to capture, analyze, interpret, and monitor medical data. This need has given rise to a process of translating names of clinical conditions into codes to assist the collection, later analysis, and comparability. For this purpose, the World Health Organization (WHO) has maintained the International Classification of Diseases (ICDs) as a world’s standard diagnostic and classification tool for epidemiology, clinical purposes, health management, and resources allocation [1•, 2].

Epidemiological data, monitoring, and evaluating health outcomes that are associated with the way medications are put on the market and used in clinical practice are essential to understand the ongoing safety and risk-benefit profiles of medications, and paramount to promoting their optimal use.

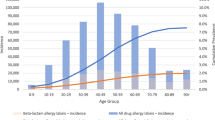

Following rising technology and knowledge in pathomechanism of diseases, new generation of drugs have been developed and vastly launched to the market. From 45 monoclonal antibodies in 2017, 75 are expected in 2020 [3]. However, in contrast to the growing knowledge in the pharmaceutical developments over the last decades, drug adverse reactions remain key challenges for health professionals and patients, and it is a significant cause of post-marketing withdrawal of drugs. Drug hypersensitivity reactions (DHR), both immune- and non-immune-mediated, can comprise 15% of all adverse drug reactions [4, 5], affect more than 7% of the general population [6••], and be pointed as the main cause of death attributed to allergies, exemplified by drug-induced anaphylaxis [7, 8••, 9].

Learning with clinical practice

In a first visit of a 41-year-old man, with no known drug allergies, he finally reaches the allergy clinic after being seen by other specialties. Twenty minutes after taking Ibuprofen 400 mg for headache, he developed the second episode of facial angioedema. He received treatment and recovered after 18–20 h. Previous episode occurred after the last intake of Aspirin, which he used to use at least once a week. The patient presented with a personal history of persistent asthma under continuous treatment for more than 15 years and, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, the reason why he underwent three ENT surgeries in the last 2 years and was prescribed at least 4 cycles of systemic antibiotics per year. Atopy was ruled out. The search for other differential diagnoses resulted negative. He underwent allergological work-up, which confirmed the hypersensitivity due to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAIDs) and found an alternative with a “coxib” NSAID.

Drug hypersensitivity reactions: definitions and terminology

The WHO first defined DHR as type B drug adverse reactions, dose-independent, unpredictable, noxious, and unintended response to a drug taken at a dose normally used in humans [10•]. Currently, DHR is known as adverse effects of pharmaceutical formulations (including active drugs and excipients) that clinically resemble allergy [11••], and drug allergies are DHRs for which a definite immunological mechanism is demonstrated [11••, 12••] (Fig. 1).

Together with β-lactam antibiotics, NSAIDs are the most common causes of drug hypersensitivity [12••]. Several sub-types of hypersensitivity to NDAIDs have been described depending on clinical patterns presented [13•, 14], which drives the clinical investigation. Our patient presented a non-allergic hypersensitivity reaction to NSAIDs. Combined with the respiratory manifestations, the final clinical hypothesis is Widal (or Samter) syndrome. This condition was first described in 1922 by Widal et al. The article was published in French, and largely ignored for the next 45 years [15]. It was not until 1968 when Samter and Beers described patients with the symptom triad of asthma, aspirin sensitivity, and nasal polyps that the condition became recognized and known as Samter’s triad [16]. Chronic hyperplastic sinusitis (enlargement caused by excessive multiplication of cells) is now considered a fourth hallmark of the disease.

Let us code applying the ICD

Most of the countries worldwide uses the ICD to monitor morbidity and mortality statistics—a reason why it is translated in more than 47 languages [10•]. Currently, the tenth edition of the ICD (or adaptations) is in use by most of these countries.

From the ICD-10 view [17], the case would be classified with a combination of disorders for the final hypothesis (J45.0 predominantly allergic asthma + J31.0 chronic rhinitis + J32.0 chronic sinusitis + J33 nasal polyp + T78.3 angioneurotic edema + Y45 analgesics, antipyretics, and anti-inflammatory drugs) since Widal/Samter syndrome is missing. For the clinical diagnosis, it would receive the out-of-date nomenclature as angioneurotic edema (T78.3) + analgesics, antipyretics, and anti-inflammatory drugs (Y45.0).

Because of its complexity, under-recognition, under-diagnosis, and/or under-notification, DHRs are under-represented in healthcare databases and coding systems, exemplified by the ICD-10. The lack of ascertainment and recognition of the importance of DHRs prevents national and international health planning, low resource allocation for clinical practice, research, and prevention in the field. This results in a poor understanding of the natural history of DHRs and impacts in realistic and comparable knowledge of their epidemiology.

Improving the representation of drug hypersensitivity reactions in the ICD-11

The 11th ICD revision was officially launched by WHO in March 2007, and the final draft is expected to be submitted to WHO’s World Health Assembly for official endorsement by 2018 [1•], but the work on refining and maintenance of the new edition is expected to take longer.

Understanding the deficiencies of the representation of allergic and hypersensitivity conditions, including the DHRs, a detailed action plan was coordinated based on scientific evidences and academic actions [2, 7, 8••, 18••, 19, 20, 21••, 22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. The ALLERGY in ICD-11 initiative was launched 6 years ago to have a better representation of these disorders in the ongoing 11th revision of the ICD. It has been supported by six major international allergy academies, named Joint Allergy Academies, and collaboration with the WHO ICD-11 revision governance has been established and is ongoing so far. The construction of the “allergic and hypersensitivity conditions” section in the ICD-11 beta draft (Fig. 2) [29••] was the main outcome of this first step of the process.

The building process of the new section, including the “drug hypersensitivity” sub-section, was a detailed and intensive process in which all the implemented conditions have been discussed with the experts representing different specialties and the WHO ICD leadership.

The “Drug hypersensitivity” sub-section is classified under the “Complex allergic or hypersensitivity conditions” and counts with 48 conditions scattered under seven domains (Fig. 2). More specification, such as chronology, severity and trigger, can be given to these conditions by combining characteristics available in the “extension codes” chapter.

Applying the new “Drug hypersensitivity” sub-section of the ICD-11

Although the corresponding ICD-11 codes are not completely locked, applying the ICD-11 logic [29••], the case would be classified as CA09.0 Samter syndrome and EJ01.1 drug-induced angioedema + XM409771066 anti-inflammatory drug non-steroidal for the acute phase of the reaction.

Perspectives of classification and coding of drug hypersensitivity

Having DHRs well represented in an international classification and coding system, endorsed by the WHO, provides specific codes to specific conditions and, therefore, facilitates the use of such classification and codes by clinicians, epidemiologists, and statisticians, as well as all data custodians and other relevant personnel. Standard and more detailed tools for population-based studies provide a common understanding regarding more accurate diagnosis and clinical outcomes to facilitate the dialog between diverse heath care sectors. It also supports clinical research by allowing increased sensitivity and specificity of profiling disorders and patients recruitment to multicentric clinical trials and pharmacogenetic studies.

Efforts to reach standard classification, coding and definitions for DHRs through the ICD-11 revision are aligned to the developments of precision medicine (PM). PM describes prevention, diagnosis, and treatment strategies that take individual variability into account. As PM advances, for some decisions, it will add the population-based best evidence in order to reach specific and detailed understanding of what makes an individual patient different from others.

Many quality measures worldwide rely on the WHO ICD codes. Increasing the specification of conditions will help clarify the connection between a provider’s performance and the patient’s condition. Accurate and updated diagnostic and procedure codes will improve data on the outcomes, efficacy, and costs of new medical technology and facilitate fair reimbursement policies for the use of this system. It will help payers and providers to more easily identify patients in need of disease management and more effectively tailor disease management programs [19]. Making specific diagnosis visible in the ICD, such as Samter/Widal syndrome, will be able to support the allocation of resources to improve diagnosis, management and research in the field.

As knowledge derived from populations is key information for decision-making, the construction of the new section addressed to DHRs in the ICD-11 will allow the collection of more accurate epidemiological data to support quality management of patients with drug allergies, and better facilitate health care planning to implement public health measures to prevent and reduce the morbidity and mortality attributable to DHRs.

Availability of data and material

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study. The ICD-11 beta draft and PubMed platforms are open to the public.

Abbreviations

- DHR:

-

drug hypersensitivity reaction

- ENT:

-

ear, nose, throat

- ICD:

-

International Classification of Diseases

- NSAIDs:

-

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- PM:

-

precision medicine

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance, •• Of major importance

• World Health Organization, International Classification of Diseases website. (cited, available: http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/accessed October 2017.) Introduces general aims and purposes of the World Health Organization classification system.

Tanno LK, Calderon MA, Goldberg BJ, Akdis CA, Papadopoulos NG, Demoly P. Categorization of allergic disorders in the new World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases. Clin Transl Allergy. 2014;4:42.

Castells M. Drug hypersensitivity and desensitization. Immunol Allergy Clin. 37(4):xvii–xviii. in press

Davies DM, Ashton CH, Rao JG, Rawlins MD, Routledge PA, Savage RL, et al. Comprehensive clinical drug information service: first year’s experience. Br Med J. 1977;1:89–90.

Lugardon S, Desboeuf K, Fernet P, et al. Using a capture–recapture method to assess the frequency of adverse drug reactions in a French university hospital. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:225–31.

•• Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters; American Academy of Allergy AaIACoA, Asthma and Immunology; Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Drug allergy: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:259–73. American experts practice parameters regarding drug allergy.

Tanno LK, Ganem F, Demoly P, Toscano CM, Bierrenbach AL. Undernotification of anaphylaxis deaths in Brazil due to difficult coding under the ICD-10. Allergy. 2012;67:783–9.

•• Tanno LK, Bierrenbach AL, Calderon MA, Sheikh A, Simons FE, Demoly P. Joint Allergy Academies. Decreasing the undernotification of anaphylaxis deaths in Brazil through the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-11 revision. Allergy. 2017;72(1):120–125.xProves the usability and accuracy of the International Classification of Diseases 11 for anaphylaxis mortality statistics.

Moneret-Vautrin DA, Morisset M, Flabbee J, et al. Epidemiology of life-threatening and lethal anaphylaxis: a review. Allergy. 2005;60:443–51.

• WHO. International drug monitoring: the role of national centres. Report of a WHO meeting. Tech Rep Ser WHO. 1972;498:1–25. World Health Organization’s pharmacovigilance activities.

•• Johansson SG, Bieber T, Dahl R, Friedmann PS, Lanier BQ, Lockey RF, et al. Revised nomenclature for allergy for global use: Report of the Nomenclature Review Committee of the World Allergy Organization, October 2003. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:832–6. Key document in the field of allergies classification.

•• Demoly P, Adkinson NF, Brockow K, Castells M, Chiriac AM, Greenberger PA, et al. Thong BYH. International consensus on drug allergy. Allergy. 2014;69:420–37. International consensus document regarding drug allergy.

• Kowalski ML, Makowska JS, Blanca M, Bavbek S, Bochenek G, Bousquet J, et al. Hypersensitivity to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)—classification, diagnosis and management: review of the EAACI/ENDA# and GA2LEN/HANNA. Allergy. 2011;66:818–29. Key document in the field of classification of hypersensitivity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Cousin M, Chiriac A, Molinari N, Demoly P, Caimmi D. Phenotypical characterization of children with hypersensitivity reactions to NSAIDs. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27(7):743–8.

Widal MF, Abrami P, Lermoyez J. Anaphylaxie et idiosyncrasie. Presse Med. 1922;30:189–92.

Samter M, Beers RF. Intolerance to aspirin: clinical studies and consideration of its pathogenesis. Ann Intern Med. 1968;68:975–83.

World Health Organization, ICD-10 version 2016 website. (cited, available: http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en accessed October 2017).

•• Tanno LK, Calderon MA, Demoly P, on behalf the Joint Allergy Academies. New allergic and hypersensitivity conditions section in the International Classification of Diseases-11. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2016;8(4):383–8. https://doi.org/10.4168/aair.2016.8.4.383. Introduced the first section addressed to allergic and hypersensitivity reaction in the history of the International Classification of Diseases

Tanno LK, Sublett JL, Meadows JA, Calderon M, Gross GN, Casale T, et al. Perspectives of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-11 in allergy clinical practice in the United States of America. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118(2):127–32.

Demoly P, Tanno LK, Akdis CA, Lau S, Calderon MA, Santos AF, et al. Global classification and coding of hypersensitivity diseases—an EAACI–WAO survey, strategic paper and review. Allergy. 2014;69:559–70.

•• Tanno LK, Calderon MA, Goldberg BJ, Gayraud J, Bircher AJ, Casale T, et al. Constructing a classification of hypersensitivity/allergic diseases for ICD-11 by crowdsourcing the allergist community. Allergy. 2015;70:609–15. Presents the building block of the construction of the first section addressed to allergic and hypersensitivity reaction in the International Classification of Diseases 11.

Tanno LK, Calderon M, Papadopoulos NG, Demoly P. Mapping hypersensitivity/allergic diseases in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-11: cross-linking terms and unmet needs. Clin Transl Allergy. 2015;5:20.

Tanno LK, Calderon MA, Demoly P, on behalf the Joint Allergy Academies. Making allergic and hypersensitivity conditions visible in the International Classification of Diseases-11. Asian Pac Allergy. 2015;5:193–6.

Tanno LK, Calderon MA, Demoly P, on behalf the Joint Allergy Academies. Optimization and simplification of the allergic and hypersensitivity conditions classification for the ICD-11. Allergy. 2016;71(5):671–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.12834.

Tanno LK, Calderon MA, Papadopoulos NG, Sanchez-Borges M, Rosenwasser LJ, Bousquet J, et al. Revisiting desensitization and allergen immunotherapy concepts for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-11. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4(4):643–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2015.12.022.

Tanno LK, Calderon MA, Li J, Casale T, Demoly P. Updating allergy/hypersensitivity diagnostic procedures in the WHO ICD-11 revision. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4(4):650–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2016.01.015.

Tanno LK, Simons FE, Annesi-Maesano I, Calderon MA, Aymé S, Demoly P, et al. Fatal anaphylaxis registries data support changes in the WHO anaphylaxis mortality coding rules. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12(1):8.

Tanno LK, Calderon M, Demoly P, Joint Allergy Academies. Supporting the validation of the new allergic and hypersensitivity conditions section of the World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases-11. Asia Pac Allergy. 2016;6(3):149–56.

•• World Health Organization, ICD-11 Beta Draft website. (cited, available: http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd11/browse/l-m/en October 2017). World Health Organization’s platform for the International Classification of Diseases 11.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to all the representatives of the ICD-11 Revision Project with whom we have been carrying on fruitful discussions, helping us to refine the classification presented here: Robert Jakob, Linda Best, Nenad Kostanjsek, Robert J G Chalmers, Jeffrey Linzer, Linda Edwards, Ségolène Ayme, Bertrand Bellet, Rodney Franklin, Matthew Helbert, August Colenbrander, Satoshi Kashii, Paulo E. C. Dantas, Christine Graham, Ashley Behrens, Julie Rust, Megan Cumerlato, Tsutomu Suzuki, Mitsuko Kondo, Hajime Takizawa, Nobuoki Kohno, Soichiro Miura, Nan Tajima, and Toshio Ogawa.

Joint Allergy Academies: American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI), European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI), World Allergy Organization (WAO), American College of Allergy Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI), Asia Pacific Association of Allergy, Asthma and Clinical Immunology (APAAACI), and Latin American Society of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (SLAAI).

Funding

This research was conducted with support from AstraZeneca, as an unrestricted AstraZeneca ERS-16-11927 grant and from MEDA Pharma through CHRUM administration.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Luciana Kase Tanno and Pascal Demoly contributed to the construction of the document (designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Luciana Kase Tanno declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Pascal Demoly declares that he has no conflicts of interest.

Human and animal rights and informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Drug Allergy

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tanno, L.K., Demoly, P. & on behalf of the Joint Allergy Academies. Lessons of Drug Allergy Management Through the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-11. Curr Treat Options Allergy 5, 52–59 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40521-018-0157-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40521-018-0157-5