Abstract

Until recently, most solid renal masses identified on imaging were presumed to be renal cell carcinomas and were treated with surgical resection. New and improved treatment modalities and advances on imaging and histological diagnostic techniques have led to a change in this paradigm. Imaging-guided biopsy is now an established step in the management of many patients with newly diagnosed renal masses. In this article, we describe a decision-making protocol to help selecting patients who should or should not undergo biopsy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The role of biopsy in the management of renal masses has been evolving over the past several years. Traditionally, biopsy was avoided due to concerns of false-negative results and needle track seeding with tumor; and surgical resection was the preferred option for the diagnosis and concomitant treatment of suspicious lesions. However, recently there has been a shift in this paradigm. Imaging-guided biopsy techniques of renal masses have been found to be safe [1], and the once feared complication of needle track seeding has been shown to be rare [1, 2]. Advances in MRI and CT have also led to improvements in non-invasive tumor characterization, allowing for better patient selection and more accurate positioning of the needle to target areas of tumor likely to yield positive results. These, coupled with improved histological analysis methods [3], have led to a decrease in false-negative results, making renal mass biopsies an important diagnostic option. Furthermore, this type of data can have an impact on emerging treatment algorithms, including thermal ablation, targeted systemic therapies, and active surveillance. In this review article, we summarize the current knowledge about renal tumor biopsy and describe the situations in which renal masses (a) should be biopsied, (b) should not be biopsied, and (c) might be biopsied, depending on the specific circumstances.

Percutaneous renal biopsy is increasingly in demand due to several factors. The number of small renal masses (<4 cm) that are incidentally detected is rising due to the increased use of cross-sectional imaging [4]. A significant proportion of these renal masses is benign, though, and requires no treatment. A series of 2770 patients that underwent radical or partial nephrectomy for sporadic lesions found 12.8 % of the overall masses were benign, and 44 % of solid renal tumors less than 1 cm in size were benign. The benign mass types included oncocytoma (72.9 %), angiomyolipoma (17.8 %), and papillary adenoma (4.3 %). In another recent study, more than 25 % of lesions measuring less than 2 cm were benign [5]. High-grade malignancy was found in only 7.6 % lesions less than 2 cm and none in lesions measuring less than 1 cm [5]. A recent meta-analysis suggests that approximately 40 % of tumors that measure less than 1 cm and about 20 % of those that measure between 1 and 4 cm are benign [6••]. Furthermore, the same authors report that the estimated number of surgically resected benign renal masses in the United States from 2000 to 2009 increased by 82 %; a number that parallels the increased rate of masses detected with imaging [7, 8].

The use of ablative therapy for treatment of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) has also increased; and most protocols require a biopsy for diagnosis and grading prior to the procedure. Furthermore, active surveillance is being used more often for management of indolent small renal tumors in elderly or infirmed patients. The choice among management options may be greatly influenced by the histology of the tumor. One algorithm designed by Halverson et al. placed patients into favorable, intermediate, and unfavorable risk groups based on biopsy [9]. Patients with favorable and intermediate risk and lesions under 2 cm were placed into active surveillance. Patients with intermediate risk lesions greater than 2 cm and unfavorable risk lesions were assigned to definitive treatment. The authors reported a 100 % agreement between biopsy and final pathology in the cohort of patients who underwent surgery.

Based on well-established indications [3] and newer imaging observations, we have grouped lesions into three groups based on biopsy recommendations.

Renal Masses That Should be Biopsied

Solid Renal Mass and Known Extrarenal Primary Malignancy, Where Treatment Will be Affected

A biopsy is done to confirm if the mass represents an extrarenal metastasis to the kidney, which would be treated by other than resection; a second primary malignancy of renal origin; or a benign mass.

Renal Mass with Metastases

A biopsy is performed to determine histology and source of primary tumor to guide choice of systemic and/or radiation therapy. One may consider biopsy of a presumed metastasis in these cases, both to confirm RCC and as proof of metastatic disease.

Renal Masses Prior to Ablative Therapy

There are several reasons for obtaining pathology prior to ablation. A definitive benign diagnosis could obviate the need for ablation and render follow-up unnecessary. Since ablation causes tissue destruction, histologic diagnosis must be obtained prior to the procedure. Frequency of imaging follow-up and prognosis may depend on the particular grade and RCC subtype. In addition, multiple ablation trials in the literature have been reported with the presumption of malignancy based on imaging alone and thus may have overestimated efficacy of ablation. Future trials should confirm the malignant status of the lesion prior to ablation.

Same-day biopsy and ablation may be up 50 % less expensive than a 2-day procedure because of the multiple procedure payment reduction Medicare rule [10].

Imaging Features Suggestive of Fat-Poor Angiomyolipoma (AML) Prior to Treatment

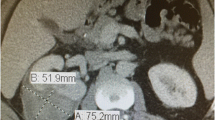

Since AMLs are usually treated with surveillance or embolization, rather than resection, pretreatment diagnosis will affect management. Approximately, 4.5 % of angiomyolipomas contain no or minimal fat [11]. Fat-poor AMLs are typically hyperdense compared to adjacent renal parenchyma and enhance homogeneously (Fig. 1) [12]. In a retrospective review of 175 lesions suspicious for RCC on CT, 6 (3 %) of the tumors were minimal-fat angiomyolipomas; and all of these tumors were homogeneously hyperdense masses that enhanced after IV contrast material injection [13]. Renal cell carcinomas are not usually hyperdense on precontrast CT scans [14].

Fat-poor AMLs have MR features that can suggest biopsy rather than unneeded resection or ablation. AMLs usually have low signal intensity on T2-weighted images and variable enhancement after gadolinium injection [15–17]. They may show signal loss on opposed-phase MR imaging [17, 18]. Most RCCs, particularly the clear cell subtype, have high signal intensity on T2-weighted images and enhance avidly [17, 19]. Some clear cell RCCs show signal loss on chemical shift imaging [17, 20], but the other MRI features are distinctively different from AMLs. Papillary RCCs do have MRI features that overlap with AMLs, in particular low signal intensity on T2-weighted MR images [17, 19, 21], and hence biopsy is used to distinguish these from AMLs. Of 100 known RCCs, only 2 % had the same imaging characteristics as minimal-fat angiomyolipomas [11], indicating that biopsy will be needed to distinguish between AML and RCC in only a small number of cases.

Renal Masses That May Require Biopsy Depending on Specific Circumstances

Bosniak III Masses

Bosniak III lesions (Fig. 2) have a reported malignancy rate between 31 and 100 % [22•]. Yet, the role of biopsy of such masses has been debated, as the relative lack of solid tissue makes non-diagnostic results more common [23]. Biopsy should be considered for patients being evaluated for resection, in particular for those patients with serious comorbidities and high operative risk [24]. In one large series, biopsy was performed in 199 cystic masses with definitive diagnosis obtained in 88 % [25]. In another series of 28 Bosniak III lesions, biopsy established a benign diagnosis and avoided unnecessary surgery in 11 patients (39.3 %) [23].

If active surveillance is undertaken instead of biopsy or treatment, the recommendation is for an initial 6-month study followed by annual studies for at least 5 years. If there is no change during that time, the mass may be considered benign [26].

Enhancing Renal Masses That Do Not Contain Fat (If Histologic Diagnosis Will Alter Treatment, or to Make an “Informed” Decision About Treatment Plans)

While the vast majority of solid renal masses without visible fat are RCCs, some imaging features do overlap with benign tumors including angiomyolipoma, oncocytoma, metanephric adenoma, and leiomyoma [27]. If definitive imaging features of RCC (see “Renal Masses That Should Not be Biopsied” section) are not present, biopsy can be considered since some tumors will be benign and treatment is not required. In some cases, patients may prefer a definitive diagnosis prior to making management decisions.

Renal Masses That Could be Focal Infection/Inflammation After Adequate Antibiotic Therapy

Infection or inflammation may appear mass-like on imaging [28]. After a trial of antibiotics, a persistent mass may be biopsied to determine the diagnosis, especially if it has imaging features atypical for RCC, such as ill-defined margins or more infiltrative growth pattern, or it occurs in a young patient [29].

Renal Masses That Should Not be Biopsied

Bosniak I, II, and IV Masses

Hundred percentage of Bosniak I and II lesions are benign (Figs. 3, 4) and if there are borderline imaging features then surveillance imaging or MRI can be used to reclassify these cystic tumors. Over 90 % of Bosniak IV lesions are malignant and, in the absence of metastasis, these lesions do not require biopsy and should be surgically extirpated or ablated (Fig. 5) [30].

Renal Masses Larger Than 7 cm That Do Not Contain Detectable Fat

Renal masses larger than 7 cm have a greater than 90 % probability of being malignant [31]. In addition, a mass of this size will likely be symptomatic due to mass effect on adjacent structures. Therefore, just as Bosniak IV lesions, these large masses should not usually undergo biopsy before treatment.

Renal Masses with Locally Aggressive Features That Appear Resectable

Nearly 10 % of RCC have tumor thrombus in the renal vein or the IVC [32]. An even less common occurrence is local invasion into adjacent structures such as the colon, pancreas, or other organs with a prevalence of 1–1.5 % [33]. The appearances of these lesions clearly have a high risk of malignancy and should not be biopsied prior to resection.

Renal Masses That Clearly Contain Macroscopic Fat

Angiomyolipomas are well-known benign lesions that can be definitively diagnosed by imaging alone. Nearly all AMLs contain fat that is detectable on CT and MRI. On MR imaging, macroscopic fat is characterized by signal loss on images obtained with fat saturation (Fig. 6). When minute quantities of fat are present, however, these suppression techniques may fail, and chemical shift MR imaging may be an alternative method to identify the fat. A thin rim of signal void on the opposed-phase images (Indian ink artifact) at the mass–kidney interface is highly specific for an AML (Fig. 6) [18].

a Axial T1-weighted in-phase MR, b axial T1-weighted opposed-phase MR, and axial T1-weighted fat-saturated MR images of a 41-year-old woman with a renal angiomyolipoma. Note signal loss on the fat-saturated image (arrow on c) and a thin rim of signal void (India ink artifact) in the interface between the kidney and the renal mass on the opposed-phase images (arrowhead on b), both characteristic of macroscopic fat

Renal Masses That Contain Intracellular Lipid

The most common type of renal malignancy is the clear cell RCC (ccRCC). Due to high intracellular lipid content, approximately 40 % of ccRCCs show relative signal loss on opposed-phase images, similar to findings seen with lipid-rich adrenal adenomas (Fig. 7). Angiomyolipoma with minimal fat may also demonstrate intracellular lipid, but these can often be differentiated from ccRCC with other MRI features. Clear cell RCC will usually demonstrate high signal intensity on T2-weighted images and avid enhancement following gadolinium injection (Fig. 7) [34]. Fat-poor AMLs typically have low signal intensity on T2-weighted MR images. Papillary RCC may present with these same characteristics and should be considered in the differential diagnosis [34].

a Axial non-contrast CT and b axial post-contrast CT images of a 67-year-old woman demonstrate an avidly enhancing clear cell RCC of the left kidney (arrows). c Axial T1-weighted in-phase MR image shows minimal hyperintense signal relative to surrounding parenchyma and d opposed-phase MR image shows signal drop out (arrows). e The tumor has high signal intensity on the axial T2-weighted MR image (arrow)

Renal Masses That Contain Hemosiderin

A recent study suggests that the detection of intracellular hemosiderin with MRI is highly specific for the diagnosis of renal malignancies; in particular papillary RCCs [35]. Hemosiderin is characterized by relative signal loss within a tumor on in-phase MR images, and its detection obviates the need for biopsy (Fig. 8).

a Axial T1-weighted in-phase MR, b axial T1-weighted opposed-phase MR, and c coronal T2-weighted MR images of a 63-year-old man with papillary RCC demonstrate the presence of hemosiderin in the tumor (arrows). Note relatively lower signal intensity on the in-phase compared to out-of-phase image; and low signal on the T2-weighted MR image

Renal Masses with Features Suggesting Urothelial Origin

While the risk of track seeding with tumor cells is negligible from biopsy of primary renal parenchymal tumors and metastases, the risk from biopsy of urothelial carcinomas is thought to be considerable. These should be suspected if they grow in an infiltrative pattern and are centered in the renal sinus (Fig. 9). Masses suspected to have urothelial origin should not be biopsied via a percutaneous route. Histologic samples of these masses are more safely obtained via urine cytology, or ureteroscopic biopsy. If these methods fail, a urogram or retrograde pyelogram should be performed and, if there is no evidence of a primary urothelial neoplasm, then percutaneous biopsy can be completed.

Vascular Masses

Aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms can mimic renal neoplasms on some imaging studies. These should not be biopsied due to the obvious risk of uncontrollable hemorrhage. Prior to biopsy of a renal tumor, a contrast-enhanced CT, an MRI, or an US study should be obtained to exclude these vascular lesions.

Special Considerations

Fine-Needle Aspirations (FNAs) Versus Core Biopsy

A non-diagnostic rate of up to 24 % for FNA has been reported [2]. Scanga and Maygarden, in a more recent study of 154 renal mass biopsy procedures, found slightly better results, with satisfactory specimen adequacy in 86 % of FNAs; core biopsies yielded satisfactory specimens in 94 % of cases [36]. Their results corroborate those of a previous study in which a higher rate of inadequate sampling was found in FNAs (11 %) versus core biopsy (3 %) [37]. Furthermore, in this study, histologic samples were compared to surgically excised masses. Upon comparison, core biopsies had a higher rate of correct histologic subtyping and nuclear grading (91 and 86 %, respectively) than FNAs (86 and 28 %, respectively) [37]. Another review of 150 consecutive renal mass biopsies indicated higher diagnostic accuracy of core biopsy than FNA (93.2 vs. 76.2 %) [38•].

Core biopsy gives more specific information than FNA for histologic tumor classification and grading [36]. In a study of 351 renal masses where both FNA and core biopsy samples were obtained, 21.6 % of the FNAs were diagnostic when the core biopsy was non-diagnostic [39]. Therefore, if on-site pathology evaluation is available, then FNA alone or in addition to core biopsies can be used to maximize diagnostic sampling and for tumor grading and subtyping. A combination of both methods may also be more useful when lymphoproliferative disorders are suspected and for cystic lesions [2].

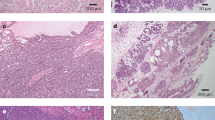

Oncocytic Renal Tumors

Caution is advised in the diagnosis of oncocytic tumors based on biopsy alone because of the subtle histologic findings of oncocytomas and a propensity for hybrid tumors [39]. Biopsy differentiation between renal oncocytoma from chromophobe RCC can be very difficult [40] and renal oncocytomas cannot be reliably differentiated from RCC on imaging studies [41, 42]. The chromophobe RCC is usually a low-grade malignancy with low metastatic potential.

Certain immunohistochemical markers have been used to distinguish between oncocytoma and RCC based on biopsy samples. Hale’s colloidal iron staining is typically positive in chromophobe RCCs and absent in oncocytoma and ccRCCs [43]. Vimentin is typically negative in oncocytomas and in chromophobe RCCs, but positive in ccRCCs. CK7 is usually positive in chromophobe RCC and negative in oncocytomas and clear cell RCC [44]. However, none of the histologic markers, or combinations of them, is universally accurate in diagnosing oncocytomas. Liu and Fanning reported that FNA findings are overlapping in oncocytomas and RCC [45]. In their study, vimentin was shown to be immunoreactive in all types of RCC. Hale’s colloidal iron staining was shown to be diffusely positive in chromophobe RCC and focally reactive in oncocytoma.

Hybrid tumors of oncocytoma and chromophobe RCC are not rare; Waldert et al. reported 16 hybrid tumors in a cohort of 91 “oncocytoma” resections [46]. Classically, hybrid renal tumors have been seen as part of the renal syndrome of Birt–Hogg–Dube or in renal oncocytosis, but they can be seen sporadically [47]. In a retrospective study of 147 solitary solid renal masses classified as benign or oncocytic, 3 % showed a coexisting hybrid malignancy [48].

Conclusion

Biopsy has a significant role in the management of renal masses given the improved histological analysis and improved targeting with advances in CT and MRI. We have described an algorithm to apply when deciding whether or not to biopsy renal masses. Renal masses that should be biopsied are essentially those for which results can guide treatment and follow-up. Lesions that should not be biopsied are those that are either clearly benign or malignant. Certain renal masses may require biopsy depending on the patient’s clinical status, or if a diagnosis will alter the treatment. FNA alone or in addition to core biopsies can be used to maximize diagnostic sampling. We expect that research will develop methods to further characterize benign and malignant lesions, thereby decreasing the number of tumors that should be biopsied and moving those into the category that should not be biopsied.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Smith EH. Complications of percutaneous abdominal fine-needle biopsy. Review. Radiology. 1991;178(1):253–8.

Volpe A, et al. Techniques, safety and accuracy of sampling of renal tumors by fine needle aspiration and core biopsy. J Urol. 2007;178(2):379–86.

Volpe A, et al. Rationale for percutaneous biopsy and histologic characterisation of renal tumours. Eur Urol. 2012;62(3):491–504.

Zagoria RJ. Imaging of small renal masses: a medical success story. Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175(4):945–55.

Rosenkrantz AB, et al. Renal masses measuring under 2 cm: pathologic outcomes and associations with MRI features. Eur J Radiol. 2014;83(8):1311–6.

•• Johnson DC, et al. Preoperatively misclassified, surgically removed benign renal masses: a systematic review of surgical series and United States population level burden estimate. J Urol. 2015;193(1):30–5. This systematic review demonstrates that the number of benign renal masses that are misclassified preoperatively based on imaging is increasing, paralleling increases in surgically resected small renal cell carcinomas. This highlights the need for more accurate diagnosis prior to surgery, which can in many cases be accomplished with biopsy.

Westphalen AC, et al. Radiological imaging of patients with suspected urinary tract stones: national trends, diagnoses, and predictors. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(7):699–707.

Tsze DS, et al. Increasing computed tomography use for patients with appendicitis and discrepancies in pain management between adults and children: an analysis of the NHAMCS. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59(5):395–403.

Halverson SJ, et al. Accuracy of determining small renal mass management with risk stratified biopsies: confirmation by final pathology. J Urol. 2013;189(2):441–6.

Heilbrun ME, et al. CT-guided biopsy for the diagnosis of renal tumors before treatment with percutaneous ablation. Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188(6):1500–5.

Jinzaki M, et al. Angiomyolipoma: imaging findings in lesions with minimal fat. Radiology. 1997;205(2):497–502.

Kim JK, et al. Angiomyolipoma with minimal fat: differentiation from renal cell carcinoma at biphasic helical CT. Radiology. 2004;230(3):677–84.

Schieda N, et al. Unenhanced CT for the diagnosis of minimal-fat renal angiomyolipoma. Am J Roentgenol. 2014;203(6):1236–41.

Ishigami K, et al. Characterization of renal cell carcinoma, oncocytoma, and lipid-poor angiomyolipoma by unenhanced, nephrographic, and delayed phase contrast-enhanced computed tomography. Clin Imaging. 2015;39(1):76–84.

Sasiwimonphan K, et al. Small (<4 cm) renal mass: differentiation of angiomyolipoma without visible fat from renal cell carcinoma utilizing MR imaging. Radiology. 2012;263(1):160–8.

Scialpi M, et al. Small renal masses: assessment of lesion characterization and vascularity on dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging with fat suppression. Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175(3):751–7.

Allen BC, et al. Characterizing solid renal neoplasms with MRI in adults. Abdom Imaging. 2014;39(2):358–87.

Israel GM, et al. The use of opposed-phase chemical shift MRI in the diagnosis of renal angiomyolipomas. Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(6):1868–72.

Pedrosa I, et al. MR classification of renal masses with pathologic correlation. Eur Radiol. 2008;18(2):365–75.

Outwater EK, et al. Lipid in renal clear cell carcinoma: detection on opposed-phase gradient-echo MR images. Radiology. 1997;205(1):103–7.

Couvidat C, et al. Renal papillary carcinoma: CT and MRI features. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2014;95(11):1055–63.

• Israel GM, Silverman SG. The incidental renal mass. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011;49(2):369–83. This is a comprehensive review of the overall management of incidental renal masses, from diagnosis to treatment.

Harisinghani MG, et al. Incidence of malignancy in complex cystic renal masses (Bosniak category III): should imaging-guided biopsy precede surgery? Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180(3):755–8.

Rybicki FJ, et al. Percutaneous biopsy of renal masses: sensitivity and negative predictive value stratified by clinical setting and size of masses. Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180(5):1281–7.

Lang EK, et al. CT-guided biopsy of indeterminate renal cystic masses (Bosniak 3 and 2F): accuracy and impact on clinical management. Eur Radiol. 2002;12(10):2518–24.

Israel GM, Bosniak MA. Follow-up CT of moderately complex cystic lesions of the kidney (Bosniak category IIF). Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181(3):627–33.

Sahni VA, Silverman SG. Imaging management of incidentally detected small renal masses. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2014;31(1):9–19.

Craig WD, Wagner BJ, Travis MD. Pyelonephritis: radiologic-pathologic review. Radiographics. 2008;28(1):255–77 quiz 327–8.

Silverman SG, et al. Renal masses in the adult patient: the role of percutaneous biopsy. Radiology. 2006;240(1):6–22.

Caoili EM, Davenport MS. Role of percutaneous needle biopsy for renal masses. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2014;31(1):20–6.

Rosoff JS, et al. Laparoscopic radical nephrectomy for renal masses 7 centimeters or larger. JSLS. 2009;13(2):148–53.

Marshall VF, et al. Surgery for renal cell carcinoma in the vena cava. J Urol. 1970;103(4):414–20.

Margulis V, et al. International consultation on urologic diseases and the European Association of Urology international consultation on locally advanced renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2011;60(4):673–83.

Sussman SK, Glickstein MF, Krzymowski GA. Hypointense renal cell carcinoma: MR imaging with pathologic correlation. Radiology. 1990;177(2):495–7.

Childs DD, et al. In-phase signal intensity loss in solid renal masses on dual-echo gradient-echo MRI: association with malignancy and pathologic classification. Am J Roentgenol. 2014;203(4):W421–8.

Scanga LR, Maygarden SJ. Utility of fine-needle aspiration and core biopsy with touch preparation in the diagnosis of renal lesions. Cancer Cytopathol. 2014;122(3):182–90.

Schmidbauer J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of computed tomography-guided percutaneous biopsy of renal masses. Eur Urol. 2008;53(5):1003–11.

• Veltri A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and clinical impact of imaging-guided needle biopsy of renal masses. Retrospective analysis on 150 cases. Eur Radiol. 2011;21(2):393–401. In this study the authors describe the diagnostic value of fine needle aspiration and core-biopsy of renal masses, the associated complications (or lack thereof), and, more importantly, highlight the fact that the procedure altered clinical management in about 70 % of patients.

Parks GE, et al. Benefits of a combined approach to sampling of renal neoplasms as demonstrated in a series of 351 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(6):827–35.

Yusenko MV. Molecular pathology of renal oncocytoma: a review. Int J Urol. 2010;17(7):602–12.

Choudhary S, et al. Renal oncocytoma: CT features cannot reliably distinguish oncocytoma from other renal neoplasms. Clin Radiol. 2009;64(5):517–22.

Rosenkrantz AB, et al. MRI features of renal oncocytoma and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195(6):W421–7.

Geramizadeh B, Ravanshad M, Rahsaz M. Useful markers for differential diagnosis of oncocytoma, chromophobe renal cell carcinoma and conventional renal cell carcinoma. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2008;51(2):167–71.

Ng KL, et al. Differentiation of oncocytoma from chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (RCC): can novel molecular biomarkers help solve an old problem? J Clin Pathol. 2014;67(2):97–104.

Liu J, Fanning CV. Can renal oncocytomas be distinguished from renal cell carcinoma on fine-needle aspiration specimens? A study of conventional smears in conjunction with ancillary studies. Cancer. 2001;93(6):390–7.

Waldert M, et al. Hybrid renal cell carcinomas containing histopathologic features of chromophobe renal cell carcinomas and oncocytomas have excellent oncologic outcomes. Eur Urol. 2010;57(4):661–5.

Pavlovich CP, et al. Renal tumors in the Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26(12):1542–52.

Ginzburg S, et al. Coexisting hybrid malignancy in a solitary sporadic solid benign renal mass: implications for treating patients following renal biopsy. J Urol. 2014;191(2):296–300.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Urogenital Imaging.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kao, J.S., Behr, S., Westphalen, A.C. et al. Renal Mass Biopsy in the Era of Surgical Alternatives. Curr Radiol Rep 3, 18 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40134-015-0102-3

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40134-015-0102-3