Abstract

After an abbreviated biography of Voegelin, the essay unfolds the six ‘key elements’ the Reader’s editors focus on. There’s Voegelin’s grounded rejection of positivism in human inquiry, his labor to recover the wisdom of the past, along with a theoretical attempt to articulate a philosophy of the conscious experiences underlying a philosophical anthropology. He explored the equivalent differentiations of this human consciousness in terms of mythic, classic philosophic, and Judeo-Christian formulations. This led him to characterize much of modernity as an attempt to immanentize the transcendent in this world rather than beyond. And underlying all of these elements was his understanding of philosophy as a participation in the eschatological movement of history,’ in conformation ‘to the Platonic-Aristotelian practice of dying.’

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

As someone who had long taught courses greatly influenced by my reading of Eric Voegelin’s works, I often dreamt of a book containing selections from his various books and articles, which would make him accessible to students and academics without the time to work through everything he has written. I am very happy to say that this is that book.

The editors’ aim with the Reader is to provide in a single volume ‘a general introduction to Voegelin’s philosophy’ (xxiv) after the publication of the thirty-four volumes of his Collected Works. The selections focus on Voegelin’s mature thought as expressed for the most part in self-contained essays, along with selections from The New Science of Politics, ‘Introductions’ to vols. 1, 2 and 4 of Order and History and the first chapter of vol. 5.

For me, re-reading the Reader’s selections was a reminder of how well Voegelin has worn with the passage of the approximately sixty years since the earliest writings excerpted here. Meeting Voegelin, as most will do through his writings, can be transformative. What the Eric Voegelin Reader does is make available in one handy volume a central selection of Voegelin’s enormous oeuvre in the philosophy of history that spreads out more majestically through the thirty four volumes of his Collected Works.

While Voegelin’s magnum opus, his five volume Order and History is well represented via his programmatic introductions to volumes 1, 2 and 4, along with the equally programmatic first chapter to the fifth volume—which is something like one of the late Beethoven quartets, pointing to what cannot be finished. But Voegelin was surely one of the most inspired essay writers in the history of philosophy, and the editors have selected some of his very best (though every Voegelin aficionado will lament this or that other essay they would like to have seen here). Along with these there is a generous taste of probably Voegelin’s best known work, The New Science of Politics. I enormously enjoyed their brief introductions to the various readings, and their always thought- provoking short quotations leading into each of the Reader’s five sections.

The editors, themselves first class Voegelin scholars, dedicate the Reader to Beverly Jarrett who, in cooperation with Ellis Sandoz, first at Louisiana State University Press and then at University of Missouri Press, ensured the monumental task of bringing out the Collected Works—to whose hard-working advisory board the Reader is also dedicated. Without these five exceptional people, one now sadly deceased, much of Voegelin’s work would have remained scattered and (particularly the five books published before World War II) largely inaccessible.

I will include here a bare bones selection of Voegelin’s writings that may help to contextualize the selections from his writings in the Reader. Born in 1901, his family moved to Vienna in 1910, and in 1919 he enrolled in the Law Faculty of the University of Vienna for a political science degree. After his doctorate under Hans Kelsen and Othmar Spann, he benefitted from scholarships to attend lectures by Gilbert Murray at Oxford in 1923, and from 1924–26 he attended lectures by Whitehead at Harvard, by Dewey—and also on genetics—at Columbia, and by John R Commons on political economy at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Having returned to Vienna, Voegelin’s first book was On the Form of the American Mind in 1928, when he was appointed Lecturer in political science, at the University of Vienna’s Law Faculty

In 1933 he provided the intellectual tools for diagnosing the anti-human implications of the current advocacy of race in Race and State and The History of the Race Idea: From Ray to Carus, both published in Germany and quickly banned there. For an Austria faced in 1936 with militant Communism on the one hand and Nazism on the other, he wrote The Authoritarian State: An Essay on the Problem of the Austrian State. His 1938 Political Religions was also banned soon after the Anschluss , and Voegelin, fired from the university, narrowly escaped the Gestapo by fleeing to Switzerland and the US. After various short term appointments in different universities, in 1942 he was appointed professor in the Department of Government at Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, where he remained until taking up the position of Director of the Institute of Political Science at the University of Munich in 1958.

Soon after his arrival in the US he began to write A History of Political Ideas, which he abandoned as theoretically inadequate, and which has now been published as eight volumes of the Collected Works. Probably his most famous single work was his 1952 The New Science of Politics: An Introduction, followed in 1956–57 by the first three volumes of Order and History: Israel and Revelation, The World of the Polis and Plato and Aristotle. The major publication of his Munich years was his 1966 Anamnesis: On the Theory of History and Politics. After his retirement from Munich he took up an endowed position at the Hoover Institution, Stanford in 1969, where he completed the fourth volume of Order and History, The Ecumenic Age (1974). He died at Stanford in 1985, leaving unfinished the final volume of Order and History, published in 1987 as In Search of Order. His Autobiographical Reflections, an extended 1973 interview conducted by Ellis Sandoz, appeared in 1989.

Hughes and Embry have written a fine ‘Introduction’ to Voegelin’s work, and note that ‘it is as a major, and unusually expansive, philosopher of existence and history that Voegelin should primarily be regarded—and as he is here presented’ (ix). They point out that ‘for the next forty years Voegelin’s work moved simultaneously in two directions: 1) expanding the scope of his understanding of human interpretations of personal, political and cosmic order through the critical study of source materials as far back as the records go; and 2) establishing and continually refining a theory of consciousness as intelligible in light of, and responsive to, all the historical data that required explanation’ (xiii). It’s this double focus, on what he elsewhere calls ‘the drama of humanity,’ that animates his theoretical quest for the intrinsic depth-meaning of ‘humanity,’ whose ‘drama’ is humanity’s range of expressing its self-understanding, from the Paleolithic to the present, in relation to the whole of reality.

Hughes and Embry’s Introduction outlines the ‘Key Elements of Voegelin’s Philosophy,’ and I will follow their six key elements, expanding them briefly with illustrations from the Reader.

‘First, Voegelin’s work is a resistance to and rejection of positivist philosophy and social science’ (xvi).’ As relevant as ever today is Voegelin’s spirited rejection of a positivist approach to political theory. He considered that positivism started from the elevation of the methods of the natural sciences to the point of excluding as irrelevant the realms of being not accessible to its methods. Rather, ‘Science starts from the prescientific existence of man, from his participation in the world with his body, soul, intellect, and spirit…and from this primary cognitive participation…rises the arduous way, the methodos, toward the dispassionate gaze on the order of being in the theoretical attitude’ (39).

Voegelin spells out three effects of this methodological restriction. There is the accumulation of non-essential facts, but far worse is ‘the operation on relevant materials under defective theoretical principles,’ leading to seriously defective interpretation creating ‘an entirely false picture because essential parts are omitted…because the critical principles of interpretation do not permit recognizing them as essential’ (43). I am reminded of his 1964 lectures on ‘Hitler and the Germans,’ where he substitutes historian Percy Schramm’s trivializing portrait of Hitler with a philosophical diagnosis of the Führer in terms of the classic philosophy of radical stupidity and wilfulness.

‘The second guiding principle of Voegelin’s thought is the necessity of recovering the wisdom of the past’ (xvii). The opening line of the first volume of Order and History states that ‘The order of history emerges from the history of order’ (290), in other words that our understanding of the meaning of humanity emerges from within the historical process of the emergence of humanity. So Voegelin’s paradoxical statement that in these matters, ‘the test of truth, to put it pointedly, will be the lack of originality in the propositions’ regarding humanity’ (205).

One of the best indications of his working method in attaining that ‘wisdom of the past’ can be found in the introduction to his 1965 Harvard lecture, ‘Immortality: Experience and Symbol.’ He is trying to indicate the human experience of transcendence, here symbolized by the word ‘immortality,’ with its roots in the language of Homeric epic. For Voegelin, the experiences underlying symbols like that—he quotes a T S Eliot conveying them with his notion of ‘The point of intersection of the timeless/ With time’ (167)—are not necessarily easily accessed.

When such symbols conveying a core depth human experience occur in an account—say of a mythic text like the Epic of Gilgamesh, a Platonic dialogue or a Gospel, ‘There is no guarantee whatsoever that the reader of the account will be moved to a meditative reconstitution of the engendering reality; one may even say the chances are slim, as meditation requires more energy and discipline than most people are able to invest’ (149). Rather, ‘their meaning can be understood only if they evoke, and through evocation reconstitute, the engendering reality in the listener or reader’ (148).

So that subsequent to (i) experiences of transcendent reality and their symbolization, there can ensue (ii) a gradual degradation of those symbols when their inner experiential substance fades. Finally, (iii) the degraded symbols—and not their original grounding experiences—provoke a sceptical reaction, since the mere symbols are offered as adequate thresholds to experiences of transcendence.

In his ‘Immortality’ essay, Voegelin notes the gradual thinning out of experiences of transcendence in the school philosophy—say of a Theophrastus—after Aristotle. So that, at the close of the 2nd century ad a Sextus Empiricus gathers together the arsenal of sceptical argument against the philosophy of the schools.

But there is a second thinning out and loss of experiences of transcendence that attaches itself to both classic philosophy and the Judeo-Christian tradition which finds its expression from late medieval nominalism through the Reformation, the wars of religion, to the sceptical reaction of the French Enlightenment. As he has said, these skeptical reactions are not to the originating experiences of transcendence, but to their emptied out symbols. A Saul Bellow character in Herzog warns us that we should not allow the visions of genius to be turned into the canned goods of the intellectuals. In the final chapter of The Ecumenic Age, Voegelin speaks of ‘the historical torment of imperfect articulation … skepticism, disbelief [and] rejection,’ adding that such a diagnosis is to help bring about ‘renaissances, renovations, rediscoveries, rearticulations, and further differentiations.’

‘The third essential element in Voegelin’s philosophy emerged into mature articulation with the explorations of consciousness first published in Anamnesis. These consolidated for him the theoretical core of the philosophical anthropology that informed all his later work…that may be summarized as follows. The most elementary fact of human existence is that it is an embodied participation in reality which is specifically formed by, and as, a conscious search for meaning…a “tension toward the ground” of its own and all existence’ (xviii). ‘Ground’ for Voegelin is his translation of Aristotle’s aition. The Reader includes an essay on ‘The Search for the Ground,’ which focuses precisely on this quest:

The quest of the ground, or ‘search of the ground’ as I formulate it, is a constant in all civilizations…That is not to say that the search for the ground, or the expressions of it, always have the same form…But at least we can express them clearly in the form that they assumed in the eighteenth century, especially with Leibniz. There the quest of the ground has been formulated in two principal questions of metaphysics. The first question is, ‘Why is there something; why not nothing?’ And the second is, ‘Why is that something as it is, and not different?’ … the first question, ‘Why is there something; why not nothing?’ becomes the great question of the existence of anything; and ‘Why is that something as it is, and not different?’ becomes the question of essence (114).

Voegelin notes three meanings for the term aition in Plato and Aristotle, the first two different aspects of ‘cause,’ while its third meaning is of ‘the ground of existence of man first of all, then also of other things…the Nous: Reason or Spirit or Intellect…the Ground of existence that is divine’ (115f).

‘[A] fourth guiding principle of his thought: his analysis of what he calls the historical “differentiation of consciousness”’ (xix). This includes ‘the explicit discovery of transcendent reality in various cultures…understood as a personal God revealed through prophets in Hebrew and Christian cultures, as the transcendent Agathon or self-sufficient Nous in Greek philosophy, and as an impersonal Brahman or Tao in Hindu and Chinese traditions respectively...’ (xix). The editors have noted how, in The New Science of Politics (a prequel for what he will be about in Order and History) Voegelin carries out this recovery of the principles of political science by identifying ‘three types of truth symbolized in ancient societies, which have provided the basis for all later Western political forms of self-understanding, to wit: “cosmological,” “anthropological,” and “soteriological” truth’ (35).

Voegelin opens The New Science of Politics with the programmatic statement that ‘The existence of man in political society is historical existence; and a theory of politics, if it penetrates to principles, must at the same time be a theory of history’ (36). While Plato, Augustine or Hegel, or the entire history of philosophy have much to teach us, the restoration of political science ‘to the dignity of a theoretical science’ requires ‘a work of theoretization that starts from the concrete historical situation of the age, taking into account the full amplitude of our empirical knowledge’ (37).

Human historical existence begins within the experience of the cosmological myth—some years later, in the Introduction to Israel and Revelation (as well as to the entire study of Order and History) he will treat the ancient Near Eastern civilizations as politically ordered in terms of ‘a cosmic analogue, as a cosmion, by letting vegetative rhythms and celestial revolutions function as models for the structural and procedural order of society’ (300–01). He drily notes that such ‘self-understanding of a society as representative of cosmic order’ recurs in history, where ‘the Communist movement’ represents ‘the truth of a historically immanent order…in the same sense in which a Mongol Khan was the representative of the truth contained in the Order of God’ (52f).

Contrasted with the order of cosmological empires is the breakthrough made by Plato. ‘A political society in existence will have to be an ordered cosmion, but not at the price of man; it should not only be a microcosmos but also a macroanthropos. This principle of Plato will briefly be referred to as the anthropological principle’ (54f). The humanity underlying this new type of society is no longer primarily measured in terms of its harmony with the order of the cosmos. Rather, ‘the true order of the soul … [is] dependent on philosophy in the strict sense of the love of the divine sophon’ (56). This means that ‘The anthropological principle…must be supplemented by a second principle for the theoretical interpretation of society. Plato expressed it when he created his formula “God is the Measure,” in opposition to the Protagorean “Man is the Measure”’ (59).

Beyond Plato’s anthropological-theological principle and Aristotle’s statement of the impossibility of friendship between God and man, Voegelin speaks of a ‘third type of truth that appears with Christianity [which] shall be called “soteriological truth”’ (62). In Christianity there is an ‘experience of mutuality in the relation with God, of the amicitia in the Thomistic sense, of the grace that imposes a supernatural form on the nature of man…’ Rather than replacing the Heraclitean-Platonic-Aristotelian form, the revelation of this grace in history, through the incarnation of the Logos in Christ intelligibly fulfilled the adventitious movement of the spirit in the mystic philosophers’ (62). The ‘Gospel and Culture’ essay (245–86) fills out Voegelin’s reflections on this soteriological truth.

‘Voegelin’s understanding of the differentiation of consciousness underlies a fifth important feature of his philosophy…his characterization of modernity in general, and of modern political thought in particular, as distorted by unrealistic and misleading portrayals of the human condition…an energetic, civilization-wide effort to relocate perfect goodness and truth from the transcendent to the worldly realm’ (xx). One of the clearest earlier versions of this was his Political Religions (see 21–23), but his earlier works on race had already diagnosed an immanentization of anthropology where the biological-racial aspect of our humanity had been allotted an essential rather than accidental role in human existence. The title of Voegelin scholar Barry Cooper’s 2004 New Political Religions, or an Analysis of Modern Terrorism indicates the continued relevance of Voegelin’s 1938 study and its later applications.

As Voegelin remarks in his Autobiographical Reflections:

If the experience of objects in the external world is absolutized as the structure of consciousness at large, all spiritual and intellectual phenomena connected with experiences of divine reality are automatically eclipsed. However, since they cannot be totally excluded—because after all they are the history of humanity—they must be deformed into propositions about a transcendental reality (30).

To turn away from the divine ground ‘means to refuse to apperceive the experience of the divine ground as constitutive of man’s reality’ which he sees in terms of ‘the mass phenomena of spiritual and intellectual disorientation in our time,’ leading to ‘the withdrawal of man from his own humanity’ (31–32). This categorization of modernity can be seen expanded in our illustration below of what the editors suggest as their final feature of Voegelin’s work.

‘Finally, a sixth feature of Voegelin’s philosophy pertains to his understanding of the very meaning of the term “philosophy.” This understanding is grounded in the classical Greek experiences that gave rise to the symbol philosophia…’ (xxi–xxii). Perhaps one of the more extended expressions of this sixth feature can be found in ‘Reason: The Classic Experience.’ There he argues that ‘The unfolding of noetic consciousness in the psyche of the classic philosophers is not an “idea,” or a “tradition,” but an event in the history of mankind … True insights concerning Reason as the ordering force in existence were certainly gained, but they had to be gained as the exegesis of the philosophers’ resistance to the personal and social disorder of the age that threatened to engulf them’ (241).

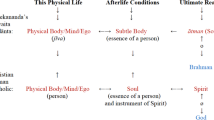

In the Appendix to that essay Voegelin presents a diagram, horizontally structured in terms of the personal, social and historical dimensions of human existence, while the left vertical column ‘lists the levels in the hierarchy of being from the Nous to the Apeiron,’ as first articulated in classic Greek philosophy, in all of which we participate (243):

Voegelin helpfully rethinks the Aristotelian form/matter dichotomy in terms of formation and foundation, where the downward arrow ‘indicates the order of formation from the top down. The arrow pointing up indicates the order of foundation from the bottom up … The arrow pointing to the right indicates the order of foundation’ (243).

For Voegelin, an adequate philosophy of the human must include all these levels and dimensions, nor should any part of the grid be erected into a determining role. Nor should the order of formation be inverted or distorted, ‘as for instance by its transformation into a causality working from the top or the bottom. Specifically, all constructions of phenomena on a higher level as epiphenomena of processes on a lower one, the so-called reductionist fallacies, are excluded as false … Specifically, all “philosophies of history” which hypostatize society or history as an absolute, eclipsing personal existence and its meaning, are excluded as false’ (243).

The grid can be used as a diagnostic tool for the various anti-rational movements of modernity. Earlier in the essay, Voegelin named thinkers like Hegel, Comte, Marx, Freud, Jung, Breton, along with Merlau-Ponty’s ‘rational’ justification of Stalin’s 1930s show trials in Humanisme et terreur, all of who he would consider as excluding whole areas of human existence by their focusing on one or other level or dimension:

For Reason can be eristically fused with any world content, be it class, race, or nation; a middle class, working class, technocratic class, or summarily the Third World; the passions of acquisitiveness, power, or sex; or the sciences of physics, biology, sociology, or psychology (239–40).

The Reader concludes with the poignant conclusion to Autobiographical Reflections:

The conceptual penetration of the sources is the task of the philosopher today…These chores—of keeping up with the problems, of analyzing the sources, and of communicating the results—are concrete actions through which the philosopher participates in the eschatological movement of history and conforms to the Platonic-Aristotelian practice of dying (392).

Eric Voegelin succeeded, after a gap of many years, to Max Weber’s chair at the University of Munich. I am certain that if his readers allow Voegelin to enter into dialogue with them, they will be more than ever encouraged to take on, if not Weber’s famous ‘politics as a vocation,’ certainly what Voegelin experienced as ‘philosophy as a vocation.’

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Purcell, B. The Eric Voegelin Reader: Politics, History, Consciousness, Selected and Edited by Charles R. Embry and Glenn Hughes. Soc 55, 368–372 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-018-0270-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-018-0270-x