Abstract

This CORR Insights™ is a commentary on the article ‘‘Can a Triple Pelvic Osteotomy for Adult Symptomatic Hip Dysplasia Provide Relief of Symptoms for 25 Years?” By van Stralen and colleagues available at DOI 10.1007/s11999-012-2701-0.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Where are we now?

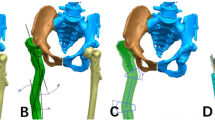

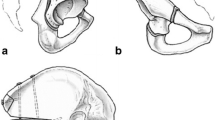

Developmental hip dysplasia (DDH) is a childhood hip disorder that refers to a spectrum of abnormalities ranging from mild acetabular dysplasia to complete hip dislocation. Treatment goals involve early reduction with the intent of providing an optimal environment for femoral head and acetabular development and minimizing the long-term sequelae of residual deformity. There is abundant evidence that residual radiographic acetabular dysplasia and/or hip subluxation in untreated patients leads to the development of secondary hip osteoarthritis with time. The degenerative changes likely develop owing to alterations in joint mechanics leading to increased contact stress. Despite successful early intervention for DDH, many treated patients end up with residual acetabular dysplasia. If diagnosed while skeletally immature the treatment consensus is with an innominate osteotomy. However, when the patient presents as a young adult with symptomatic residual acetabular dysplasia and minimal to no degenerative changes then the treatment is much more controversial. Much of this controversy stems from the lack of long-term followup studies of different treatment interventions for this age group.

Where do we need to go?

The article by Van Stralen et al. attempts to address one of the main shortcomings in the DDH literature, the lack of long-term followup studies. The authors provide a mean 25 year followup study of 43 skeletally mature patients treated with a triple pelvic osteotomy for symptomatic residual acetabular dysplasia after initial treatment for DDH in childhood. Although the authors noted patients in general had initial improvement in symptoms many went on to have osteoarthritis of the hip requiring further management including THA. This raises the question regarding whether a triple osteotomy of the pelvis can improve long-term outcomes of patients with residual dysplasia or alter the known natural history of this disorder. With this in mind, treating physicians need to be armed with information on the long-term effects of other joint preserving operations used for this patient group to better understand whether a given intervention can influence an otherwise adverse outcome in a positive way. The lack of evidence for the efficacy of current treatment options makes informed decision difficult for patients.

How do we get there?

It is clear that despite the prevalence of acetabular dysplasia and the morbidity that it can cause if left untreated, we have much to learn about the long-term effects of current treatment strategies for our young adult patient population with this disorder. We need long-term studies critically assessing outcomes of different pelvic osteotomies that have been used for decades and compare the results with one another and with the natural history of acetabular dysplasia without treatment. Do our interventions make a positive difference? Additionally, we need to design thoughtful studies to investigate newer treatment strategies such as the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy to correct acetabular deficiency and hip arthroscopy to address labral disorders and femoroacetabular impingement that can be sources of pain in patients with residual hip dysplasia. Finally we need to learn more about the genetics of acetabular dysplasia and explain why some patients may respond better to different treatment options. This would allow for the development of new classification systems that would be more prognostic and allow individualized treatment strategies to be implemented based on a person’s unique genetic risk factors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The author certifies that he, or a member of his immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

This CORR Insights™ comment refers to the article available at DOI 10.1007/s11999-012-2701-0.

About this article

Cite this article

Dobbs, M.B. CORR Insights™: Can a Triple Pelvic Osteotomy for Adult Symptomatic Hip Dysplasia Provide Relief of Symptoms for 25 Years?. Clin Orthop Relat Res 471, 591–592 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-012-2702-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-012-2702-z