Abstract

Purpose of Review

Chronic musculoskeletal pain (CMP) attributable to conditions such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, and chronic low back pain is the most common cause of disability globally, for which no effective remedy exists. Although acupuncture is one of the most popular sensory stimulation therapies and is widely used in numerous pain conditions, its efficacy remains controversial. This review summarizes and expands upon the current research on the therapeutic properties of acupuncture for patients with CMP to better inform clinical decision-making and develop patient-focused treatments.

Recent Findings

We examined 16 review articles and 11 randomized controlled trials published in the last 5 years on the clinical efficacy of acupuncture in adults with CMP conditions. The available evidence suggests that acupuncture does have short-term pain relief benefits for patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis and chronic low back pain and is a safe and reasonable referral option. Acupuncture may also have a beneficial role for fibromyalgia. However, the available evidence does not support the use of acupuncture for treating hip osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

Summary

The majority of studies concluded the superiority of short-term analgesic effects over various controls and suggested that acupuncture may be efficacious for CMP. These reported benefits should be verified in more high-quality randomized controlled trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chronic musculoskeletal pain attributable to conditions such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, and chronic low back pain is the most common cause of disability with significant economical and societal implications globally [1,2,3]. Despite this critical public health burden, no effective medical treatments exist for these chronic pain conditions. The current care offered to patients with chronic pain is inadequate with treatment largely consisting of pharmacological analgesics that have known toxicities [4, 5]. Finding new and effective interdisciplinary treatments to alleviate pain for this high-risk population is a national priority as highlighted by an Institute of Medicine report nearly a decade ago [5].

Acupuncture, originating in China more than 3000 years ago, is one of the most popular sensory stimulation therapies. It is an ancient treatment technique of inserting and manipulating fine needles to stimulate specific anatomic points to facilitate the recovery of health [6]. Each year, an estimated 3 million American adults receive acupuncture treatment, with chronic musculoskeletal pain being the most common condition for which this therapy is used [7]. Recently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services agreed to cover acupuncture for Medicare patients with chronic lower back pain [8••]. However, evidence for the effectiveness of acupuncture for the relief of pain is inconsistent across a range of common musculoskeletal pain presentations.

In the past decade, a considerable number of large-scale clinical trials and meta-analyses of the published literature have supported the safety and effectiveness of acupuncture to treat musculoskeletal pain. The true efficacy of acupuncture for reducing symptoms associated with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, and other pain conditions remains controversial [9, 10]. Given ongoing unresolved debate about the clinical effectiveness of acupuncture and methodological concerns with numerous prior studies, we performed an updated review of the latest available evidence on acupuncture for chronic musculoskeletal pain published between 2016 and 2020 in order to determine the clinical efficacy of this treatment and to better inform healthcare providers.

Literature Search

To update the current clinical evidence regarding the effects of acupuncture on musculoskeletal pain, a comprehensive search of English databases from January 2016 until June 2020 and reference lists was performed based on our previous work [11]. The search terms used were acupuncture, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, chronic musculoskeletal pain, randomized controlled trial, and clinical trial. We considered only randomized controlled trials of adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain published in English that reported original data. All studies had at least one control arm: a sham-controlled acupuncture; a waiting list (people who did not receive acupuncture until the end of treatment); a type of active therapy; or comparisons with their normal routine care (see Box 1 Controls in acupuncture clinical trials). Sample sizes were ≥ 20 and had the presence of pain as measured by specific clinical primary endpoints. We also included any type of review, including overviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses published in the last 5 years. To help optimize the consistency of our review, we have excluded articles focused on dry needling (acupuncture at a local point instead of a standard acupoints) or acupuncture with heating (moxibustion) (see Box 2 Types of acupuncture and associated methods).

Box 1 Controls in acupuncture clinical trials [65, 66]

Nontreatment control | Patients usually received nontreatment, delayed treatment (waiting list), usual care, or/and rescue medication in consideration of medical ethics |

Noninsertion sham control (placebo acupuncture needles) | These do not penetrate the skin, but usually use the blunt end of the acupuncture needles, noninsertion sham devices (e.g., Streitberger or Park sham devices), and other needle-resembling devices such as toothpicks and needling guiding tubes |

Insertion sham control (placebo acupuncture needles) | Usually involves a superficial insertion of needles to acupoints or nonacupoints |

Positive comparison or active control | Refers to active treatments, such as specific mediations and physiotherapies, some usual care, or standardized care, which were thought to be effective |

Combined controls | Combined noninsertion and insertion sham |

Box 2 Types of acupuncture and associated methods [67,68,69,70,71,72]

Traditional acupuncture | The acupuncture practiced as a healing modality of traditional Chinese medicine is the most common form used in the USA. Stimulation of acupoints, most of points lie on a meridian, helps correct and rebalance the “flow of energy” or qi |

Electrical acupuncture or electroacupuncture | Electrode attached to the acupuncture needle to provide continued stimulation |

Laser acupuncture | Stimulation of acupuncture points with low-intensity, nonthermal laser irradiation |

Acupoint injection | Bee venom or herbal extract injected into acupoint for treatment |

Dry needling | Insertion of filiform needle into the skin and muscle directly at a myofascial trigger point to help relieve pain |

Moxibustion | It bakes acupoints with burning moxa wool to dredge meridians and regulate qi-blood to help prevent and cure a variety of conditions |

Results

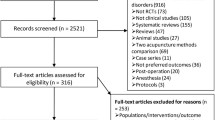

We identified 200 abstracts including 104 clinical trials and 96 review articles published from 2016 to 2020. Relevant abstracts and papers were reviewed and eleven randomized controlled trials [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23] and 16 review articles met the eligibility criteria. These included patients who were diagnosed with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and fibromyalgia, and with chronic low back pain conditions.

Table 1 summarizes the evidence reviewed according to types of conditions. Eleven randomized controlled trials present original primary research published from 2016 to 2020. All the participants met the ACR criteria for the classification of osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and fibromyalgia. Table 2 includes the characteristics of all overviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses related to different types of chronic musculoskeletal pain [9, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38].

Acupuncture for Osteoarthritis

Four randomized trials and three review articles have examined the clinical efficacy of acupuncture in patients with osteoarthritis. The studies were conducted in the USA, Indonesia, China, and Egypt and were published between 2016 and 2020 (Table 1). Among the four clinical trials, two used traditional acupuncture and two used laser acupuncture (defined as the stimulation of traditional acupuncture points with low-intensity, nonthermal laser irradiation). All four trials used placebo needles (noninsertion sham control or a superficial insertion of needles to acupoints or nonacupoints) as the controls. In one small Chinese study, there was no significant difference in the improvement rate of pain, 61.9% in the traditional acupuncture group and 42.9% in the sham control (p = 0.217) [14]. However, in the three other trials, statistically or clinically significant improvements in pain and function based on various measures were demonstrated when traditional acupuncture or laser acupuncture was compared with controls (2–3 times per week for 4–5 weeks) [12, 13, 15].

Similarly, the most recent summary overview in 2019 that synthesized high-quality evidence from 12 systematic reviews, totaling 246 randomized trials, concluded that acupuncture may have a significant improvement on short-term benefits (length of follow-up was not reported) when compared with western medicine in treating knee osteoarthritis (risk ratio = 2.35, 95% confidence interval [1.59, 3.45], p < .0001) [28•]. A 2017 meta-analysis of 17 trials also showed that acupuncture was associated with a significant reduction in chronic knee pain when compared with standard care or combined with other modalities [26]. The results of the meta-analysis of three studies showed that acupuncture significantly reduced chronic knee pain at 12 weeks on both the WOMAC pain subscale (mean difference − 1.12, 95% CI − 1.98 to − 0.26) and visual analog scale pain (mean difference − 10.56, 95% CI − 17.69 to − 3.44) when compared with no treatment [26]. Compared with active interventions and placebo, two additional systematic reviews with moderate-quality evidence also supported the positive effects of acupuncture or electroacupuncture for osteoarthritis of the knee [24, 25]. In contrast, a Cochrane review published in 2018 of 2 sham-controlled or 4 active-controlled trials with 413 participants. The combined analysis of two sham-controlled RCTs with 120 participants found acupuncture has little or no effect in reduction in pain for acupuncture relative to sham acupuncture (standardized mean difference 0.13 (95% CI − 0.49 to 0.22). The four other RCTs were unblinded comparative effectiveness trials, which compared (additional) acupuncture with four different active control treatments. All results were evaluated at short term (i.e., 4 to 9 weeks after randomization). Because of low-quality evidence, the effects of acupuncture for people with hip osteoarthritis when compared with education, exercise, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are uncertain [27•].

Overall, substantial evidence to date demonstrates that 6 or more sessions of acupuncture treatment have short-term benefits for relief of pain for knee osteoarthritis when compared with Western medicine or sham acupuncture. Acupuncture appears to be a reasonable referral option for patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. However, the available evidence does not support that acupuncture can help patients with symptomatic hip osteoarthritis.

Acupuncture for Rheumatoid Arthritis

The two recent randomized controlled trials and several review articles published in the last 5 years investigating acupuncture for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) were reviewed. One of the latest trials was conducted in Portugal that included 105 patients with long-standing RA. Patients were randomly assigned to three groups: a traditional acupuncture, a sham-controlled acupuncture (placebo needles), or a waiting list arm. Patients underwent a total of nine acupuncture sessions over four consecutive weeks. The authors found a significant improvement in patient’s self-reported pain, tender joint count, hand grip strength, and health status in the acupuncture group compared with the sham control or waiting list group [17]. The second randomized trial included 30 patients with RA conducted in Egypt that compared laser acupuncture with reflexology control. Patients received either laser acupuncture or reflexology treatment three times per week for four consecutive weeks. Patients who underwent laser acupuncture experienced significantly reduced disease activity, improved joint range of motion, and improved quality of life when compared with the reflexology group. In addition, improved biomarkers such as decreased plasma MDA (malondialdehyde, an oxidative marker) and increased plasma ATP (adenosine triphosphate, antioxidant marker) were also observed in the acupuncture group when compared with those randomly assigned to the reflexology group [16].

Despite favorable results in the two new trials, however, multiple earlier clinical trials did not observe any significant improvement in improving disease activity and pain with acupuncture over sham acupuncture for RA. A number of systematic reviews evaluating two decades worth of published literature were unable to draw firm conclusions for a role of acupuncture for the treatment of RA [39,40,41,42]. For example, an overview reported conflicting and insufficient evidence exists in placebo-controlled trials questioning the efficacy of acupuncture for RA [29]. The most recent overview of seven systematic reviews of 20 randomized trials also concluded that acupuncture probably has little or no impact in the treatment of RA [30•]. These conclusions are consistent with the findings of acupuncture in RA reported previously [9, 43].

The discrepancy among these studies may be related to the complexities and severity of the disease condition, the lack of standardized treatment protocols for types of acupuncture, dose and intensity of the needle insertion, treatment duration, and choice of comparison groups. Therefore, the effectiveness of acupuncture in the treatment of RA remains uncertain and needs to be further determined in future well-designed large studies.

Acupuncture for Fibromyalgia

Since 2016, six randomized trials conducted in the USA, Spain, Turkey, and Italy have examined the clinical efficacy of acupuncture among 488 adults with fibromyalgia [18,19,20,21,22,23]. In the control groups, four studies used placebo needles (insertion sham acupuncture or nonpenetrating needles) as the controls [18,19,20, 22], one used group education [21], and the most recent study, published in 2020, compared acupuncture with the use of nutraceuticals in 55 patients with fibromyalgia [23]. Taken as a whole, these studies suggest that acupuncture treatment (4 to 13 weeks, once or twice a week) may be associated with a significant decrease in pain and improvement of fibromyalgia symptoms compared with a variety of controls. One study also observed significant changes in serum serotonin and substance p values after 8 sessions of acupuncture treatment [22]. In addition, 4 studies reported a significant improvement in depression, functional capacity, and quality of life compared with placebo treatment [18, 19, 21, 22]. None of the trials reported any major adverse effects associated with 4–10-week acupuncture treatment. An updated systematic review and meta-analysis including 12 RCTs published in 2019 also concluded that acupuncture was more effective in relieving pain in both the short and long term compared with conventional medication [32•]. In contrast, one review including four RCTs published between 2012 and 2017 indicated that there was insufficient evidence to confirm the efficacy of acupuncture therapy for fibromyalgia, mainly due to the small number of studies [31].

Overall, recent evidence suggested that acupuncture may have a beneficial role for fibromyalgia. However, the studies on the effectiveness of acupuncture for fibromyalgia symptoms are somewhat mixed to date, with high levels of heterogeneity in control conditions or populations studied and findings should be interpreted with caution.

Acupuncture for Chronic Low Back Pain

In contrast to osteoarthritis, RA, and fibromyalgia, the number of acupuncture trials for low back pain is substantial. A considerable number of systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials performed over the last two decades found positive effects of acupuncture therapy as a treatment for chronic low back pain (Table 2). In the past 5 years, evidence from 7 overviews, summarizing about 300 randomized controlled trials, consistently demonstrated that acupuncture provides short-term clinically relevant benefits for pain relief and functional improvement when compared with sham or placebo, standard care, or other types of controls (no treatment or acupuncture plus another conventional intervention) [9, 33,34,35,36,37,38]. None of the studies reported serious adverse events during acupuncture treatment for patients with chronic low back pain. In addition, some evidence suggests acupuncture may have the potential to help reduce opioid dosage [49]. There was also some evidence of the cost-effectiveness of acupuncture in patients with chronic low back pain [35].

As a characteristic nonpharmaceutical option against the opioid crisis, acupuncture captured particularly concerning in back pain relief compared with other musculoskeletal conditions such as osteoarthritis, RA, and fibromyalgia. Accumulating evidence from the large number of well-designed trials addressing acupuncture treatment for low back pain supports the use of acupuncture as an effective option for patients with chronic low back pain and its routine incorporation into clinical practice, either alone or as an adjunct to other interventions. Nonpharmacological intervention which includes acupuncture is therefore recommended as first-line treatment [50]. This conclusion is in keeping with the January 2020 decision by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services covering up to 12 sessions over a period of 90 days for patients with chronic low back pain, with an additional 8 sessions for those who demonstrate improvement [8••].

Implications and Opportunities

Acupuncture has attracted increasing attention for the treatment of painful conditions in recent decades that has prompted a growing number of clinical trials [7]. The available evidence compiled in this updated review demonstrates that acupuncture is safe and well-tolerated in adults and has short-term benefits for patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, and chronic low back pain. The evidence is insufficient to support the use of acupuncture for treating hip osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. These findings are important for clinical practice in that physicians are able to explore potential new approaches and rethink their strategies to provide the best care for patients with chronic pain conditions. The reported benefits from many of these trials should be verified in future large, well-controlled studies. Further work is also needed to understand the underlying mechanisms by which acupuncture can improve clinical symptoms.

Explanatory mechanisms from Eastern and Western biological theories have provided a supposed rationale for the effectiveness of acupuncture to treat the musculoskeletal disorders related to chronic pain [12, 44, 46, 51,52,53, 54]. Modern acupuncture research on pain mechanisms indicates that the analgesic effects of acupuncture activate peripheral and central pain control systems by releasing various endogenous opioids or nonopioid compounds. Considerable evidence has shown that acupuncture analgesia may be imitated by stimulation of nerves, which, in turn, triggers endogenous opioid mechanisms [45, 47, 48]. Recent functional magnetic resonance imaging studies further demonstrate that acupuncture has regionally specific, quantifiable effects on relevant structures and restoration of the balance in the connectivity of the human brain implicated in descending pain modulation, and altered pain-related attention and memory [12, 55,56,57].

The field can continue to improve by applying the revised Standards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA) guidelines [58], in addition to using the following recommendations. Future large-scale studies should have double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial designs, use appropriate control groups (such as physiologically inactive, yet credible shams), validate long-term outcome measures, and have prolonged and systematic follow-up to better understand the long-term effects of the acupuncture therapies. The training experience and licensure status of acupuncturists in both Eastern and Western countries should be recorded and taken into account. Standardized and generalizable treatment protocols should be developed and, importantly, dose/intensity superiority studies should be carried out in patients with musculoskeletal pain. Additionally, the explication of mechanisms of the physiological and biological effects of acupuncture in musculoskeletal pain needs to be further determined [59,60,61].

Practical Aspects of Accessing Acupuncture Treatments

Cumulative evidence suggests that acceptance of acupuncture therapies is growing. Patients and providers are increasingly interested in the use of acupuncture because of their potential as an effective remedy for reducing pain while improving physical and psychological health and well-being [62, 63]. The three principal barriers preventing patients from accessing these integrative treatments in the USA include uncertainties about the methods, costs, and where to procure these services [64].

Thus, it is important that the evidence behind these treatments be discussed fairly with patients so that they can make an informed decision. Out-of-pocket costs for integrative medicine services can be high and often are not covered by insurance. Still, many health insurance plans are beginning to include some discounts or rebates for these services as the evidence for efficacy grows.

A growing number of physicians are receiving dual training in both Western and Eastern medicine, which is beneficial for patients uncertain of how to integrate the two philosophies. When selecting a provider offering acupuncture treatments, the two most important characteristics for patients to consider are general experience and experience in treating musculoskeletal disorders. Acupuncture should not be a replacement for conventional care or be used to postpone seeking medical advice. As the demand and evidence for acupuncture therapies grow, educating healthcare providers and patients about the evidence and clinical implications for these remedies is vital. By providing practical information about methods, costs, and experience, providers can effectively encourage their patients to explore the options for integrating Western and Eastern medicines.

In summary, the pathophysiological basis of acupuncture for chronic musculoskeletal pain is complex and multifaceted and symptomatic chronic pain is heterogeneous. Emerging evidence from clinical studies suggests that acupuncture is a safe and effective treatment for patients with pain of origin. Integrative approaches combine the best of conventional medicine and integrative medicine to ultimately improve patient care. These modalities may lead to the development of better strategies to reduce chronic musculoskeletal pain.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, Nahin R, Mackey S, DeBar L, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults. United States. CDC MMWR. 2016;67(36):1001–6.

Watkins EA, Wollan PC, Melton LJ 3rd, Yawn BP. A population in pain: report from the Olmsted County health study. Pain Med. 2008;9:166–74.

Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;380(9859):2163–96.

Rosenquist R. Use of opioids in the management of chronic non-cancer pain. In: UpToDate® 2020 UpToDate, Inc. and/or its affiliates. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/use-of-opioids-in-the-management-of-chronic-non-cancer-ain? 1. Accessed 14 Jun 2020.

Institute of Medicine. Relieving pain in America: a blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. The National Academies Press, Washington 2011. http://www.nap.edu/read/13172/chapter/1. Accessed 14 Jun 2020.

Kaptchuk TJ. Acupuncture: theory, efficacy, and practice. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(5):374–83. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00010.

Nahn RL, Barnes PM, Stussman BA. Expenditures on complementary health approaches: United States, 2012. Natl Health Stat Report. 2016;95:1–11.

•• CMS finalizes decision to cover acupuncture for chronic low back pain for Medicare beneficiaries. Decision Memo for Acupuncture for Chronic Low Back Pain (CAG-00452N). In: CMS.gov. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-finalizes-decision-cover-acupuncture-chronic-low-back-pain-medicare-beneficiaries. Accessed 14 Jun 2020. This new policy demonstrates acupuncture providing pain relief for chronic low back patients which is vital to address the opioid crisis.

• Chen L, Michalsen A. Management of chronic pain using complementary and integrative medicine. BMJ. 2017;357:j1284. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j1284This review summarizes research on the mechanisms of action and clinical studies on the efficacy of acupuncture in chronic back pain, neck pain, and rheumatoid arthritis. The authors emphasize how acupuncture may impact multiple pathways of the central and peripheral nervous system and future modulation of chronic pain.

•• Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, Oatis C, Guyatt G, Block J, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.41142This updated ACR guideline reflects advances in management of arthritis with a new conditional recommendation for acupuncture for knee osteoarthritis.

Zhang Y, Wang C. Acupuncture for chronic musculoskeletal pain: a review of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019; 71 https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/acupuncture-for-chronic-musculoskeletal-pain-a-review-of-randomized-controlled-trials/. Accessed 16 June 2020.

Chen X, Spaeth RB, Freeman SG, Scarborough DM, Hashmi JA, Wey HY, et al. The modulation effect of longitudinal acupuncture on resting state functional connectivity in knee osteoarthritis patients. Mol Pain. 2015;11:67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12990-015-0071-9.

Helianthi DR, Simadibrata C, Srilestari A, Wahyudi ER, Hidayat R. Pain reduction after laser acupuncture treatment in geriatric patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Med Indones. 2016;48(2):114–21.

Lin LL, Li YT, Tu JF, Yang JW, Sun N, Zhang S, et al. Effectiveness and feasibility of acupuncture for knee osteoarthritis: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2018;32(12):1666–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215518790632.

Mohammed N, Allam H, Elghoroury E, Zikri EN, Helmy GA, Elgendy A. Evaluation of serum beta-endorphin and substance P in knee osteoarthritis patients treated by laser acupuncture. J Complement Integr Med 2018 5;15(2).doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/jcim-2017-0010.

Adly AS, Adly AS, Adly MS, Serry ZMH. Laser acupuncture versus reflexology therapy in elderly with rheumatoid arthritis. Lasers Med Sci. 2017 Jul;32(5):1097–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-017-2213-y.

Seca S, Patrício M, Kirch S, Franconi G, Cabrita AS, Greten HJ. Effectiveness of acupuncture on pain, functional disability, and quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis of the hand: results of a double-blind randomized clinical trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(1):86–97. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2018.0297.

Vas J, Santos-Rey K, Navarro-Pablo R, Modesto M, Aguilar I, Campos MÁ, et al. Acupuncture for fibromyalgia in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. Acupunct Med. 2016;34(4):257–66. https://doi.org/10.1136/acupmed-2015-010950.

Uğurlu FG, Sezer N, Aktekin L, Fidan F, Tok F, Akkuş S. The effects of acupuncture versus sham acupuncture in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Acta Reumatol Port. 2017;42(1):32–7.

Zucker NA, Tsodikov A, Mist SD, Cina S, Napadow V, Harris RE. Evoked pressure pain sensitivity is associated with differential analgesic response to verum and sham acupuncture in fibromyalgia. Pain Med. 2017;18(8):1582–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnx001.

Mist SD, Jones KD. Randomized controlled trial of acupuncture for women with fibromyalgia: group acupuncture with traditional Chinese medicine diagnosis-based point selection. Pain Med. 2018;19(9):1862–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnx322.

Karatay S, Okur SC, Uzkeser H, Yildirim K, Akcay F. Effects of acupuncture treatment on fibromyalgia symptoms, serotonin, and substance P levels: a randomized sham and placebo-controlled clinical trial. Pain Med. 2018;19(3):615–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnx263.

Schweiger V, Secchettin E, Castellani C, Martini A, Mazzocchi E, Picelli A, et al. Comparison between acupuncture and nutraceutical treatment with Migratens® in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Nutrients. 2020;12:821. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030821.

Lin X, Huang K, Zhu G, Huang Z, Qin A, Fan S. The effects of acupuncture on chronic knee pain due to osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98:1578–85. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.15.00620.

Shim JW, Jung JY, Kim SS. Effects of electroacupuncture for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:1–18.

Zhang Q, Yue J, Golianu B, Sun Z, Lu Y. Updated systematic review and meta-analysis of acupuncture for chronic knee pain. Acupunct Med. 2017;35(6):392–403. https://doi.org/10.1136/acupmed-2016-011306.

• Manheimer E, Cheng K, Wieland LS, Shen X, Lao L, Guo M, et al. Acupuncture for hip osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5:CD013010. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013010The authors observe that acupuncture probably has little or no effect in reducing pain or improving function relative to sham acupuncture in people with hip osteoarthritis.

• Li J, Li YX, Luo LJ, Ye J, Zhong DL, Xiao QW, et al. The effectiveness and safety of acupuncture for knee osteoarthritis: an overview of systematic reviews. Medicine. 2019;98(28):e16301. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000016301A total of 12 systematic reviews (totaling 246 randomized trials) were synthesized. The authors concluded that acupuncture had more short-term effects and less adverse reactions compared with western medicine in treating knee OA according to high-quality evidence.

Fernández-Llanio Comella N, Fernández Matilla M, Castellano Cuesta JA. Have complementary therapies demonstrated effectiveness in rheumatoid arthritis? Reumatol Clin. 2016;12(3):151–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reuma.

• Ramos A, Domínguez J, Gutiérrez S. Acupuncture for rheumatoid arthritis. Medwave. 2018;18(6):e7284. https://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2018.06.7283An overview of 7 systematic reviews of 20 randomized trials and the authors concluded that acupuncture probably has little or no impact in RA.

Aman MM, Jason Yong R, Kaye AD, Urman RD. Evidence-based non-pharmacological therapies for fibromyalgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2018;22(5):33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-018-0688-2.

• Zhang XC, Chen H, Xu WT, Song YY, Gu YH, Ni GX. Acupuncture therapy for fibromyalgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Pain Res. 2019;12:527–42 Acupuncture therapy is an effective and safe treatment and can be recommended for the management of fibromyalgia.

Yuan QL, Wang P, Liu L, Sun F, Cai YS, Wu WT, et al. Acupuncture for musculoskeletal pain: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of sham-controlled randomized clinical trials. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30675.

Vickers AJ, Vertosick EA, Lewith G, MacPherson H, Foster NE, Sherman KJ, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: update of an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Pain. 2018;19(5):455–74.

Lorenc A, Feder G, MacPherson H, Little P, Mercer SW, Sharp D. Scoping review of systematic reviews of complementary medicine for musculoskeletal and mental health conditions. BMJ Open. 2018;8(10):e020222. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020222.

Lemmon R, Hampton A. Nonpharmacologic treatment of chronic pain: what works? J Fam Pract. 2018;67(8):474–83.

Xiang Y, He JY, Tian HH, Cao BY, Li R. Evidence of efficacy of acupuncture in the management of low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo- or sham-controlled trials. Acupunct Med. 2020;38(1):15–24. https://doi.org/10.1136/acupmed-2017-011445.

• Li YX, Yuan SE, Jiang JQ, Li H, Wang YJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of effects of acupuncture on pain and function in non-specific low back pain. Acupunct Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/acupmed-2017-011622There are 25 RCTs in 7587 participants with low back pain prior to February 2018. The authors conclude that acupuncture appears to be effective for low back pain.

Lautenschlager J. Acupuncture in treatment of inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Z Rheumatol. 1997;56:8–20.

Kelly RB. Acupuncture for pain. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:481–4.

Lee MS, Shin BC, Ernst E. Acupuncture for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47:1747–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ken330.

Zanette SA, Born IG, Brenol JC, Xavier RM. A pilot study of acupuncture as adjunctive treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:627–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-007-0759-y.

Wang C, de Pablo P, Chen X, Schmid C, McAlindon T. Acupuncture for pain relief in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(9):1249–56.

Zhang R, Lao L, Ren K, Berman BM. Mechanisms of acupuncture electroacupuncture on persistent pain. Anesthesiology. 2014;120:482–503. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000000101.

Mayer DJ, Price DD, Rafii A. Antagonism of acupuncture analgesia in man by the narcotic antagonist naloxone. Brain Res. 1977;121:368–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(77)90161-5.

Ben H, Li L, Gao XY, He W, Rong PJ. Comparison of NO contents and cutaneous electric conduction quantity at the acupoints and the nonacupoints. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. 2009;34:383–6 392.

Chen L, Zhang J, Li F, Qiu Y, Wang L, Li YH, et al. Endogenous anandamide and cannabinoid receptor-2 contribute to electroacupuncture analgesia in rats. J Pain. 2009;10:732–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.012.

Huang C, Wang Y, Chang JK, Han JS. Endomorphin and mu-opioid receptors in mouse brain mediate the analgesic effect induced by 2 Hz but not 100 Hz electroacupuncture stimulation. Neurosci Lett. 2000;294:159–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S03043940(00)01572-X.

Zheng Z, Gibson S, Helme RD, Wang Y, Lu DS, Arnold C, et al. Effects of electroacupuncture on opioid consumption in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Pain Med. 2019;20(2):397–410. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pny113.

Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(7):514–30.

Han JS, Terenius L. Neurochemical basis of acupuncture analgesia. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1982;22:193–220. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pa.22.040182.001205.

Han SH, Yoon SH, Cho YW, Kim CJ, Min BI. Inhibitory effects of electroacupuncture on stress responses evoked by tooth-pulp stimulation in rats. Physiol Behav. 1999;66:217–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9384(98)00276-5.

Zijlstra FJ, van den Berg-de Lange I, Huygen FJ, Klein J. Anti-inflammatory actions of acupuncture. Mediat Inflamm. 2003;12:59–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/0962935031000114943.

Wang KM, Yao SM, Xian YL, Hou ZL. A study on the receptive field of acupoints and the relationship between characteristics of needling sensation and groups of afferent fibres. Sci Sin [B]. 1985;28:963–71.

Egorova N, Gollub RL, Kong J. Repeated verum but not placebo acupuncture normalizes connectivity in brain regions dysregulated in chronic pain. Neuroimage Clin. 2015;9:430–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2015.09.012.

Cao J, Tu Y, Orr SP, Lang C, Park J, Vangel M, et al. Analgesic effects evoked by real and imagined acupuncture: a neuroimaging study. Cereb Cortex. 2019;29(8):3220–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhy190.

Chen X, Spaeth RB, Retzepi K, Ott D, Kong J. Acupuncture modulates cortical thickness and functional connectivity in knee osteoarthritis patients. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6482. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06482.

MacPherson H, Altman DG, Hammerschlag R, Youping L, Taixiang W, White A, et al. Revised STandards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA): extending the CONSORT statement. PLoS Med. 2010;7(6):e1000261. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000261.

Liu L, Skinner M, McDonough S, Mabire L, Baxter GD. Acupuncture for low back pain: an overview of systematic reviews. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:328196.

Vickers AJ, Linde K. Acupuncture for chronic pain. JAMA. 2014;311:955–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.285478.

Babatunde OO, Jordan JL, Van der Windt DA, Hill JC, Foster NE, Protheroe J. Effective treatment options for musculoskeletal pain in primary care: a systematic overview of current evidence. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0178621. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178621 eCollection 2017.

Zhang Y, Lao L, Chen H, Ceballos R. Acupuncture use among American adults. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:710750.

Austin S, Ramamonjiarivelo Z, Qu H, Ellis-Griffith G. Acupuncture use in the United States: who, where, why, and at what price? Health Mark Q. 2015;32(2):113–28.

The future of the public’s health in the 21st century. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Assuring the Health of the Public in the 21st Century. Washington: National Academies Press (US); 2002.

Chen H, Ning Z, Lam WL, Lam WY, Zhao YK, Yeung JWF, et al. Types of control in acupuncture clinical trials might affect the conclusion of the trials: a review of acupuncture on pain management. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 2016;9(5):227–33.

Lund I, Lundeberg T. Are minimal, superficial or sham acupuncture procedures acceptable as inert placebo controls? Acupunct Med. 2006;24(1):13–5.

Zhang H, Han G, Litscher G. Traditional acupuncture meets modern nanotechnology: opportunities and perspectives. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019;2019:2146167. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/2146167.

Waldman S. Pain review. 1st ed. Saunders: Elsevier; 2009.

Dharmananda S Electro-acupuncture. 2002. http://www.itmonline.org/arts/electro.htm. Accessed 10 August 2020.

Jelinkova H Laser for medical applications. Woodhead Publishing; 2013.

Dommerholt J, del Moral OM, Grobli C. Trigger point dry needling. J Manual Manipulative Ther. 2006;14(4):E70–87.

Deng H, Shen X. The mechanism of moxibustion: ancient theory and modern research. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:379291. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/379291.

Funding

Dr. Wang is supported by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health (NIH, R01AT006367, R01AT005521 and K24AT007323) and the Rheumatology Research Foundation. The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health. The organizations mentioned here did not have any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Wang, C. Acupuncture and Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. Curr Rheumatol Rep 22, 80 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-020-00954-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-020-00954-z