Abstract

Increasing utilization of interventional techniques in managing chronic spinal pain, specifically facet joint interventions and sacroiliac joint injections, is a major concern of healthcare policy makers. We analyzed the patterns of utilization of facet and sacroiliac joint interventions in managing chronic spinal pain. The results showed significant increase of facet joint interventions and sacroiliac joint injections from 2000 to 2014 in Medicare FFS service beneficiaries. Overall, the Medicare population increased 35 %, whereas facet joint and sacroiliac joint interventions increased 313.3 % per 100,000 Medicare population with an annual increase of 10.7 %. While the increases were uniform from 2000 to 2014, there were some decreases noted for facet joint interventions in 2007, 2010, and 2013, whereas for sacroiliac joint injections, the decreases were noted in 2007 and 2013. The increases were for cervical and thoracic facet neurolysis at 911.5 % compared to lumbosacral facet neurolysis of 567.8 %, 362.9 % of cervical and thoracic facet joint blocks, 316.9 % of sacroiliac joints injections, and finally 227.3 % of lumbosacral facet joint blocks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2014, facet and sacroiliac joint interventions were the second most commonly performed procedures, constituting 47.2 % of all interventional techniques, increasing from 28.9 % in 2000, superseding epidural injections and adhesiolysis procedures, which decreased from 58.6 % in 2000 to 45.2 % in 2014 [1••]. This is occurring with a backdrop of facet and sacroiliac joint interventions being some of the most hotly contested interventional procedures. Areas of challenge include their escalating utilization, diagnostic accuracy, and therapeutic effectiveness in managing chronic spinal pain [2, 4–6, 8, 10, 13–16 1••, 3•, 7••, 9•, 11•, 12•, ]. Moreover, this issue is larger than the interventional management of pain; the prevalence and disability secondary to spinal pain and its resultant costs continue to capture the attention of the public-at-large, physicians, regulators, and payer community [17•, 18–32]. The study by Freburger et al. [23], comparing low back pain in 1992 and 2006, showed an overall increase of 162 %, increasing from 3.9 to 10.2 %. Studies of burden of disease collaborators in the USA and across the globe showed spinal pain occupying three of the first five categories of disability [17•, 33, 34]. In fact, in the global burden of disease and disability studies [17•, 33], the prevalence of chronic low back pain was shown to be 9.4 % of the overall population, severe chronic low back pain constituting 17 % of these patients. Similarly, the neck pain prevalence was shown to be 4.9 % of the population with a significant proportion suffering with chronic neck pain with high disability [34].

Among the various interventions that are considered as excessive in managing chronic spinal pain, facet joint interventions feature prominently [1••, 2, 4–6 3•, ]. Manchikanti et al. [1••] showed an overall increase in facet and sacroiliac joint interventions of 313 % per 100,000 Medicare population with an annual increase of 10.7 % from 2000 to 2014. Assessing the increase in facet joint interventions, Manchikanti et al. [5] showed a 383 % growth in services and a 308 % growth per 100,000 Medicare population with annual increases of 15.4 or 13.6 % from 2000 to 2011. Among them, the highest increases were observed for cervical and thoracic facet joint neurolysis at a rate of 836 %, an annual increase of 22.5 %, 544 %, with an annual rate of 18.4 % for lumbosacral radiofrequency thermoneurolysis, followed by increase of cervical/thoracic facet joint injections of 359 % with an annual increase of 14.9 % with comparatively lesser increases of lumbosacral facet joint blocks with 228 % and an annual increase of 11.4 %. They also showed sacroiliac joint interventions to increase 331 % from 2000 to 2011 per 100,000 Medicare population with an annual increase of 14.2 % [6].

The explosive growth of facet joint interventions was addressed in various ways including an Office of Inspector General (OIG) investigation [3•, 5, 35–37], multiple local coverage determinations (LCDs), and across the board denials of these procedures by some payers. Questions raised about facet and sacroiliac joint interventions include those related to accuracy of the diagnosis and efficacy of the treatment modalities applied. Despite the evidence derived from multiple diagnostic accuracy studies and systematic reviews of the accuracy of controlled diagnostic blocks, numerous issues have been raised in reference to the value and validity of these techniques [1••, 10, 13–16 9•, 11•, 12•, ]. Similarly, the efficacy and effectiveness of various modalities applied in managing facet joint and sacroiliac joint pain has been vigorously debated [8, 10, 38 9•, 11•, ]. However, the OIG assessment and recommendations, multiple LCDs, and changes in the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code definitions appear to have not deterred the growth of facet joint and sacroiliac joint interventions in Medicare population in the USA on a long-term basis [1••, 2, 4–6, 35–37, 39–42 3•, ].

This assessment is undertaken to review the utilization patterns from 2000 to 2014 of facet joint and sacroiliac joint interventions in the USA in the fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare population.

Materials and Methods

This analysis of data of utilization patterns of facet and sacroiliac joint interventions was performed following the reporting standards of Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidance [43]. Institutional review board (IRB) approval was not required for this assessment and was thus not sought due to public use files (PUF) or non-identifiable data, which is non-attributable and non-confidential, available through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) database [44].

Study Design

The analysis of patterns of utilization and variables of facet and sacroiliac joint interventions was designed utilizing STROBE guidance [43], in the FFS Medicare population in the USA from 2000 to 2014.

Setting

The study uses the United States CMS database of specialty utilization from 2000 to 2014 data files of FFS Medicare [44].

Participants

All the FFS Medicare recipients from 2000 to 2014 were included in this analysis. This is a 100 % sample.

Measures

Services were defined as submitted, allowed, denied, and those with zero payments. Allowed services constituted total services after deletion of denied services and services with zero payments

For each procedure, total allowed services and rates per 100,000 were calculated for the corresponding year.

The current procedure codes for facet joint interventions and sacroiliac joint blocks were utilized. The CPT codes utilized included facet joint interventions and sacroiliac joint blocks (64470, 64472, 64475, 64476, 64490, 64491-new, 64492-new, 64493-new, 64494-new, 64495-new, 64622, 64623, 64626, 64627, 64633-new, 64634-new, 64635-new, 64636-new, 27096). These codes were identified for years 2000 to 2014. The utilization data was also assessed based on the place of service, either the facility which included ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) and hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs) or a non-facility setting—the office. The data was analyzed for overall services for each technique, and rate of services for 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries, and based on the individual primary or specialty.

Variables

Variables assessed in this evaluation included the assessment of the Medicare population and increase in Medicare population from 2000 to 2014, utilization of facet and sacroiliac joint interventions procedures in the various regions of the spine including cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral spine, and sacroiliac joint. Specialty characteristics and the settings in which the procedures were performed, influence of bundling of codes, and newly implemented LCDs were also assessed as additional variables.

The description of various specialities included in this analysis incorporated multiple specialties representing interventional pain physicians and others, interventional pain management −09, pain management −72, anesthesiology −05, physical medicine and rehabilitation −25, neurology −13, and psychiatry −26, were described as interventional pain management. Orthopedic surgery −20, general surgery −17, and neurosurgery −14 were incorporated into surgical specialities. Diagnostic radiology −30 and interventional radiology −94 encompassed radiologic specialties. Finally, other physicians were grouped into a single separate group as general physicians, whereas all non-physician providers were grouped as other providers.

Data Sources

The data for years 2000 to 2014 obtained from the CMS physician supplier procedure summary master data files provides data of all FFS Medicare participants, above and below the age of 65, receiving facet and sacroiliac joint interventions. This sample does not include medicare advantage patients.

Bias

This analysis was conducted with the internal resources of the primary author’s practice. There was no external funding. The American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) purchased the data from CMS. These data files were 100 % data sets, providing data of utilization by CPT code with modifier usage, speciality codes, place of service, Medicare carrier number, total services, and charges submitted, allowed, and denied, and amount paid, are expected to be unbiased and also unpredictable in terms of identification of any patient characteristics.

Study Size

This is a large analysis with inclusion of all patients in the Medicare FFS system receiving facet and sacroiliac joint interventions for spinal pain from 2000 to 2014.

Data Compilation

Microsoft Access 2003 and Microsoft Excel 2003 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) were utilized for data compilation.

Results

Population Characteristics

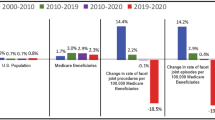

As shown in Table 1, the number of Medicare beneficiaries increased from 39.632 million in 2000 to 53,500 million in 2014, an increase of 35 % compared to an increase of 13 % in the US population. The disabled population on Medicare below age 65 increased at an annual rate of 3.7 % with a total increase of 65.7 %, compared to those over 65 with an annual increase of 1.9 % and total increase of 30.2 %.

Facet joint and sacroiliac joint interventions (services) in Medicare recipients increased 457.7 % from 2000 to 2014. Facet joint and sacroiliac joint interventions increased from 1072 per 100,000 in 2000 to 4430 per 100,000 in 2014, a 313.3 % increase. In 2000, 67 % of procedures were performed in facility settings, whereas in 2014, only 50 % were performed in facility settings. As shown in Table 2, sacroiliac joint injections in FFS Medicare recipients increased 462.8 % from 2000 to 2014. Rate per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries of sacroiliac joint injections increased from 125 in 2000 to 521 in 2014, a total increase of 316.9 %, with an annual increase of 10.7 %. In addition, Table 2 also showed the utilization rate for facet joint interventions increased 457.3 % with a rate of 312.8 % per 100,000 Medicare population from 2000 to 2014 and an annual increase rate of 10.7 % per 100,000 Medicare population, similar to sacroiliac joint injections.

Utilization Characteristics

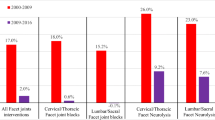

The majority of the procedures and rate per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries (84.3 % in 2000 and 79.6 % in 2014) were performed in the lumbosacral region, with cervical and thoracic procedures constituting 15.8 % in 2000 and 20.5 % in 2014. The most commonly performed procedures were subsequent lumbar facet joint/nerve blocks CPT 64475 or 64493 and 64476 or 64494 or 64495, with 60 % in 2000 and 47.5 % in 2014. Cervical/thoracic facet joint/nerve blocks (CPT 64470 or 64490, 64472, 64491, or 64492) increased 362.9 % and lumbar facet joint injection/nerve blocks increased 227.3 % per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries from 2000 to 2014 (Table 3 and Fig. 1). Cervical/thoracic facet neurolysis increased 911.5 %, and lumbar facet neurolysis increased 567.8 % per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries from 2000 to 2014 (Table 4 and Fig. 1). The rate of lumbar/sacral and cervical/thoracic facet joint injections declined 16.9 and 14.8 % in 2010 and 0.4 and 3.6 % in 2013.

Figure 1 illustrates the increase of various facet joint interventions and sacroiliac joint interventions and interventional pain management services from 2000 to 2014.

Specialty Characteristics

Figure 2 and Appendices 1 and 2 illustrate the increase in the utilization of facet and sacroiliac joint interventions by various specialty groups assigned as interventional pain management, surgery, radiology, general physicians, and others from 2000 to 2014. Across the country, 78.5 % of combined facet and sacroiliac joint interventions were performed by interventional pain management physicians in 2000 and 91.0 % in 2014.

State Utilization Characteristics

Table 5 and Appendices 3–6 show the frequency of utilization of facet and sacroiliac joint interventions from 2008 to 2014 based on Medicare part B carrier data for 2014 per 100,000 Medicare population. The utilization of facet and sacroiliac joint interventions varied from a reduction of 5.3 and 21.2 % in Cahaba and First Coast Services jurisdictions to an increase of 4.7 % to 23.3 % for other carriers. Noridian, with extensive regulations, showed a 6.4 % increase, with a 3.8 % increase for facet joint interventions. Appendices 3, 5, and 6 show utilization patterns by state based on highest utilization to lowest utilization in descending order.

Site of Service Utilization

Facet and sacroiliac joint interventions are provided in multiple settings including HOPDs, ASCs, and in physician’s offices (in-office). There has been a significant shift over the years in the facet joint interventions based on the location of the performance. In 2002, HOPD services constituted 40 %, with ASCs providing 18.3 % of the service, and in-office was 41.7 %. Since then, the HOPD share decreased to 23.1 %, with the ASC share increasing to 26.9 % and in-office share dramatically increasing to 50 % from 2002 to 2014 as shown in Appendices 7 and 8.

Discussion

The assessment of utilization patterns of facet and sacroiliac joint interventions in the FFS Medicare population continued to show alarming growth patterns from 2000 through 2014, with an increase of 313.3 % per 100,000 Medicare population from 2000 to 2014 similar to our previous reports [2, 4–6, 45]. The growth patterns are centered with overall growth of facet joint interventions with significant decreases in facet joint injections in 2010 of 14.8 % in the lumbar/sacral and 16.9 % in the cervical and thoracic spine per 100,000 Medicare recipients, with negligible decreases compared to 2011 for 2012 and 2013 with re-establishing increases in 2014 for facet joint interventions, whereas a small decrease was observed for sacroiliac joint interventions from 2012 to 2013 with an increase in 2014.

This analysis of claims of utilization essentially illustrates larger growth patterns of facet neurolysis with 911.5 % for cervical and thoracic, 567.8 % for lumbosacral, radiofrequency neurotomy from 2000 through 2014 compared to growth rate of 362.9 % for cervical/thoracic facet joint nerve blocks, 227.3 % of lumbosacral facet joint injections, and 316.9 % for sacroiliac joint injections. Overall the growth patterns have shown an increase of 312.8 % per 100,000 Medicare recipients with an annual increase of 10.7 % for facet joint interventions. However, sacroiliac joint interventions continued to increase with utilization with a rate of 316.9 or 10.7 % per year.

The results show similar patterns across the regions and specialties as shown in our previous evaluations [2, 4–6]. While explosive growth of facet joint interventions, specifically of radiofrequency neurotomy and lumbar transforaminal epidural injections, has been illustrated in the past [1••, 2 ,4-6] by proponents and opponents of the procedures, the methodology used to curb these increases without affecting the access has been variable. Some insurers have attempted to completely eliminate therapeutic facet joint interventions and encouraged radiofrequency neurotomy, and some CMS LCD policies have increased the limits in the therapeutic phase of facet joint injections from 4 to 5 per year with all of them seeming to either affect the access or increase the utilization [35, 36, 45]. These activities are very similar to the controls established in the early stages of opioid usage stating that they were utilizing guidance from boards of medical licensure, the Joint Commission Accreditation on Health care Organizations (JCAHO), and others, only to see increases of 400 % and escalating deaths [25, 46, 47]. Finally, with opioids escalating growth, adverse factors have been recognized and certain steps have been taken by multiple states to regulate opioid usage and by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) changing hydrocodone from schedule III to II [25, 46, 47]. Paradoxically, the FDA also has encouraged increased utilization by approving Zohydro and multiple other long-acting opioids [47] with misinterpretation of essential evidence of prevalence of chronic persistent pain and disability. Bodies as auspicious as The Institute of Medicine (IOM) [18] have misinterpreted the data originally published by Gaskin and Richard [19]. Essentially, IOM has estimated the prevalence and cost of chronic pain based on prevalence and costs of not only moderate and severe pain 21 % but also joint pain 33 %, arthritis 25 %, and functional disability 12 %, leading to overblown estimations of disease burden. In fact, based on this study, the population suffering with moderate and severe pain was approximately 44 million, instead of 100 million, with a cost of $100 billion instead of $650 billion [47].

The results of this assessment show an overwhelming increase in utilization patterns of facet joint interventions and sacroiliac joint injections in general and cervical/thoracic and lumbar/sacral radiofrequency neurotomy in particular, ranging from a 227 % increase for lumbosacral facet joint blocks to 912 % for cervical/thoracic facet joint neurolysis. Comparatively, the population of the USA increased 13 % from 2000 to 2014, whereas the elderly population over 65 years of age increased 31.7 %. During this period, the elderly population increased to 16.8 % of the population, but Medicare beneficiaries constituted 19.8 %, increasing from 14 % in 2000.

Among the Medicare beneficiaries, the increases were 30.2 % for those aged over 65, whereas for those disabled individuals younger than 65 years of age, the growth rate was 65.7 %. Comparatively, epidural injections increased 99 % from 2000 to 2014 per 100,000 Medicare population with interlaminar epidural injections increasing 9 % with an annual rate of 0.6 %. Further, the growth patterns of facet joint and sacroiliac joint interventions reversed the long-standing dominance of epidural procedures, transforming facet and sacroiliac joint interventions into the number one place of most commonly performed interventional techniques. It is of major concern that while lumbosacral facet joint injections increased 277.3 % and cervical/thoracic facet joint blocks increased 362.9 %, lumbosacral facet joint facet neurolysis increased 567.8 % and finally cervical and thoracic facet neurolysis increased a whopping 911.5 %. Even then, the numbers of services performed were predominantly lumbosacral facet joint blocks (47.5 %), followed by lumbosacral radiofrequency neurotomy (20.3 %) and cervical and thoracic facet joint blocks (15.4 %). However, radiofrequency neurotomy procedures are twice as expensive as facet joint blocks, even though the relief patterns are also double that of facet joint blocks, but, in cervical region due to the avoidance of bilateral facet joint radiofrequency neurotomy in the same setting, the costs of radiofrequency neurotomy may be even higher.

While these patterns of increase show an exponential growth, these patterns are similar to our previous assessments [2, 4–6 3•, ]. In the past, some evaluations [48, 49] focused on the lumbar spine assessment and lack of evidence; however, with numerous developments in evidence synthesis and explosive utilization patterns in cervicothoracic as well, the previous assessments may no longer be valid. Among the more recent assessments, Beckworth et al. [39] also showed significant increases in utilization; however, their analysis artificially inflated the number of procedures performed [40] by utilizing duplicate services, thus increasing the number of services utilized by one third. They also concluded that the changes in the CPT coding were uniquely responsible for decreases in 2010. While this is a possibility, we believe that the OIG assessment and its warnings had a significant effect on the utilization patterns [35]. Interestingly, multiple measures with LCDs [3•, 36, 37, 45] and multiple negative publications [38] seem to have no significant effect on utilization patterns. We would therefore posit that future strategies to restrain the growth include appropriate understanding of the literature, accuracy of diagnostic interventions with controlled diagnostic blocks and 80 % pain relief as the criterion standard, proper assessment of therapeutic interventions utilizing unbiased methodological quality criteria assessment in systematic reviews, appropriate determination of indications and medical necessity, and finally development of clinically relevant, evidence-based guidelines and coverage policies [1••, 2, 4–6, 8, 10, 50–65 3•, 7••, 9•, 11•, 12•, ].

Beyond the particulars described above, various researchers have indicated that there has in fact not been an increase in chronic pain [22, 23]. While the IOM indicated that the prevalence of chronic persistent pain to be affecting one third of the US population, other data has focused on the approximately 30 million individuals with significant disability. Freburger et al. [23] also have shown increases in the low back pain in North Carolina from 3.9 to 10.2 % in 1992 and 2006 showing an overall increase of 162 %. These assumptions are important as perception feeds into the reality of increases in the utilization of various management strategies designed to treat chronic pain [50–61]. Thus, proponents argue that the prevalence of chronic pain is increasing along with the evidence for diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Utilizing appropriate quality assessment measures in systematic reviews, there has been significant evidence of the value and validity of diagnostic and therapeutic facet joint interventions, even though the evidence is only moderate for diagnostic sacroiliac joint interventions and limited for therapeutic sacroiliac joint interventions [7••, 8, 10, 13–16, 50–61 9•, 11•, 12•, ]. Thus, facet and sacroiliac joint interventions performed in contemporary interventional pain management settings with proper indications and medical necessity may be the key to obtaining appropriate utilization. The discordant evidence illustrated may be dependent on interpretation of the placebo, long-term/short-term, and statistical analysis utilized by different groups due to lack of standardization and variable interpretation of methodologists and clinicians [7••, 8, 10, 13, 14, 62–72, 74–78, 80 9•, 11•, 12•, 73••, 79•, ].

Multiple limitations of assessment include lack of inclusion of Medicare Advantage participants constituting approximately 20 to 30 % of Medicare patients, potential coding errors, and lack of appropriate and identifiable coding patterns for sacroiliac joint interventions other than sacroiliac joint injections. However, the major advantage of this assessment is that we have included all patients in the FFS Medicare which included both the elderly population as well as the disabled population. This inclusion often is crucial as the disabled population tends to be higher utilizers [81].

In summary, the growth of facet and sacroiliac joint interventions continues. Thus, appropriate evidence synthesis and application of principles demonstrating medical necessity are crucial in managing the growth patterns into the future.

Conclusion

This assessment showed significant increases in facet joint and sacroiliac joint intervention utilization patterns of 313.3 % per 100,000 Medicare population from 2000 to 2014 compared to an overall Medicare beneficiary increase of 35 %. Further analysis also showed that lumbosacral facet joint blocks increased 227.3 %, compared to cervical and thoracic facet joint blocks of 362.9 %; however, increases of lumbosacral neurolysis were shown to be more dramatic with 567.8 % for lumbosacral facet neurolysis and 911.5 % for cervical and thoracic facet neurolysis. Sacroiliac joint injections increased 316.9 %.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Hirsch JA. Utilization of interventional techniques in managing chronic pain in medicare population from 2000 to 2014: an updated analysis of patterns of utilization. Pain Phys. 2016;19:E531–46. This is the latest manuscript describing the utilization of interventional techniques in managing chronic pain in the Medicare population. This updated analysis details various categories of procedures and their patterns of utilization.

Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Falco FJE, Hirsch JA. An updated assessment of utilization of interventional pain management techniques in the Medicare population: 2000–2013. Pain Phys. 2015;18:E115–27.

Manchikanti L, Helm II S, Singh V, Hirsch JA. Accountable interventional pain management: a collaboration among practitioners, patients, payers, and government. Pain Phys. 2013;16:E635–70. This manuscript describes a collaboration among practitioners, patients, payers, and government to simultaneously achieve accountable interventional pain management, reduce overwhelming growth, increase quality, and maintain patient access to care.

Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Falco FJE, Hirsch JA. Growth of spinal interventional pain management techniques: analysis of utilization trends and Medicare expenditures 2000 to 2008. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013;38:157–68.

Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Singh V, Falco FJE. Assessment of the escalating growth of facet joint interventions in the Medicare population in the United States from 2000 to 2011. Pain Phys. 2013;16:E365–78.

Manchikanti L, Hansen H, Pampati V, Falco FJE. Utilization and growth patterns of sacroiliac joint injections from 2000 to 2011 in the Medicare population. Pain Phys. 2013;16:E379–90.

Boswell MV, Manchikanti L, Kaye AD, Bakshi S, Gharibo CG, Gupta S, et al. A best-evidence systematic appraisal of the diagnostic accuracy and utility of facet (zygapophysial) joint injections in chronic spinal pain. Pain Phys. 2015;18:E497–533. This manuscript is a comprehensive review of the available literature and provides a best evidence systematic appraisal of the diagnostic accuracy and utility of facet, or zygapophysial, joint injections in chronic spinal pain. The reviewed manuscripts were assessed for quality and were graded using evidence-based principles of best evidence synthesis.

Manchikanti L, Kaye AD, Boswell MV, Bakshi S, Gharibo CG, Grami V, et al. A systematic review and best evidence synthesis of the effectiveness of therapeutic facet joint interventions in managing chronic spinal pain. Pain Phys. 2015;18:E535–82.

Simopoulos TT, Manchikanti L, Gupta S, Aydin SM, Kim CH, Solanki D, et al. Systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic effectiveness of sacroiliac joint interventions. Pain Phys. 2015;18:E713–56. This manuscript provides a systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic effectiveness of sacroiliac joint interventions. This is a comprehensive review of randomized controlled trials, diagnostic accuracy studies, and observational studies. Only modest evidence was found for diagnosis validity and treatment with radiofrequency neurotomy.

Manchikanti L, Hirsch JA, Kaye AD, Boswell MV. Cervical zygapophysial (facet) joint pain: effectiveness of interventional management strategies. Postgrad Med. 2016;128:54–68.

Manchikanti L, Hirsch JA, Falco FJ, Boswell MV. Management of lumbar zygapophysial (facet) joint pain. World J Orthop. 2016;7:315–37. This comprehensive manuscript provides evidence for the diagnostic validity and therapeutic utility of lumbar facet joint interventions.

Rubinstein SM, van Tulder M. A best-evidence review of diagnostic procedures for neck and low-back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22:471–82. This manuscript provides a best evidence review of diagnostic procedures for neck and low back pain which also included procedures related to diagnosing facet joint pain. This manuscript is from the authors of Cochrane reviews, indicating the importance and value of diagnostic facet joint interventions.

Carragee EJ, Haldeman S, Hurtwitz E. The pyrite standard: the Midas touch in the diagnosis of axial pain syndromes. Spine J. 2007;7:27–31.

Bogduk N. In defense of King et al.: the validity of manual examination in assessing patients with neck pain. Spine J. 2007;7:749–52. author reply (Carragee EJ) 752–3.

Hancock MJ, Maher CG, Latimer J, Spindler MF, McAuley JH, Laslett M, et al. Systematic review of tests to identify the disc, SIJ or facet joint as the source of low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:1539–50.

Engel AJ, Bogduk N. Mathematical validation and credibility of diagnostic blocks for spinal pain. Pain Med. 2016.

US Burden of Disease Collaborators. The state of US health, 1999–2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310:591–608. This manuscript is a comprehensive review of the US Burden of Disease Collaborators rating low back pain as number one and neck pain among the top 5 conditions of disability. It also reports on the present state of spinal pain and disability.

Institute of Medicine (IOM). Relieving pain in America: a blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011.

Gaskin DJ, Richard P. The economic costs of pain in the United States. J Pain. 2012;13:715–24.

Manchikanti L, Singh V, Falco FJE, Benyamin RM, Hirsch JA. Epidemiology of low back pain in adults. Neuromodulation. 2014;17:3–10.

Martin BI, Turner JA, Mirza SK, Lee MJ, Comstock BA, Deyo RA. Trends in health care expenditures, utilization, and health status among US adults with spine problems, 1997–2006. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:2077–84.

Buchbinder R, Blyth FM, March LM, Brooks P, Woolf AD, Hoy DG. Placing the global burden of low back pain in context. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:575–89.

Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Agans RP, Darter JD, Wallace AS, Castel LD, et al. The rising prevalence of chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:251–8.

U.S. Social Security Administration. Annual statistical report on the Social Security Disability Insurance Program, 2011. Release July 2012. www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/di_asr/2011/di_asr11.pdf.

Manchikanti L, Kaye AM, Kaye AD. Current state of opioid therapy and abuse. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016;20:34.

Rajaee SS, Bae HW, Kanim LE, Delamarter RB. Spinal fusion in the United States: analysis of trends from 1998 to 2008. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012;37:67–76.

Bae HW, Rajaee SS, Kanim LE. Nationwide trends in the surgical management of lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013;38:916–26.

Yoshihara H, Yoneoka D. National trends in the surgical treatment for lumbar degenerative disc disease: United States, 2000 to 2009. Spine J. 2015;15:265–71.

Deyo RA, Von Korff M, Duhrkoop D. Opioids for low back pain. BMJ. 2015;350:g6380.

Dart RC, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, Parrino MW, Severtson SG, Bucher-Bartelson B, et al. Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:241–8.

Atluri S, Sudarshan G, Manchikanti L. Assessment of the trends in medical use and misuse of opioid analgesics from 2004 to 2011. Pain Phys. 2014;17:E119–28.

Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64:1378–82.

Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, Blyth F, Woolf A, Bain C, et al. The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:968–74.

Hoy D, March L, Woolf A, Blyth F, Brooks P, Smith E, et al. The global burden of neck pain: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1309–15.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Inspector General (OIG). Medicare Payments for Facet Joint Injection Services (OEI-05-07-00200). September 2008. http://www.oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-07-00200.pdf.

Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC. Local Coverage Determination (LCD). Facet joint injections, medial branch blocks, and facet joint radiofrequency neurotomy (L33842). Effective Date: 3/5/2014.

Manchikanti L, Falco FJE, Benyamin RM, Gharibo CG, Candido KD, Hirsch JA. Epidural steroid injections safety recommendations by the Multi-Society Pain Workgroup (MPW): more regulations without evidence or clarification. Pain Phys. 2014;17:E575–88.

Chou R, Hashimoto R, Friedly J, Fu Rochelle, Dana T, Sullivan S, Bougatsos C, Jarvik J. Pain management injection therapies for low back pain. Technology Assessment Report ESIB0813. (Prepared by the Pacific Northwest Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. HHSA 290-2012-00014-I.) Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; March 20, 2015. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coverage/DeterminationProcess/Downloads/id98TA.pdf

Beckworth WJ, Jiang M, Hemingway J, Hughes D, Staggs D. Facet injection trends in the Medicare population and the impact of bundling codes. Spine J 2016; Mar 10. [Epub ahead of print]

Manchikanti L, Hirsch JA. Inaccurate information on facet joint injections in the Medicare population. Letter to the Editor RE: Beckworth WJ et al. Facet injection trends in the Medicare population and the impact of bundling codes. Spine J 2016 Mar 10. Spine J. 2016; in press.

Hirsch JA, Leslie-Mazwi TM, Nicola GN, Barr RM, Bello JA, Donovan WD, et al. Current procedural terminology; a primer. J Neurointerv Surg. 2015;7:309–12.

Hirsch JA, Donovan WD, Leslie-Mazwi TM, Nicola GN, Manchikanti L, Silva 3rd E. Component coding and the neurointerventionalist: a tale with an end. J Neurointerv Surg. 2013;5:615–9.

Vandenbroucke JP, Von Elm E, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Gac Sanit. 2009;23:158.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. www.cms.hhs.gov/home/medicare.Asp

Manchikanti L, Falco FJE, Benyamin RM, Helm II S, Singh V, Hirsch JA. Value-based interventional pain management: a review of Medicare national and local coverage determination policies. Pain Phys. 2013;16:E145–80.

Manchikanti L, Atluri S, Hansen H, Benyamin RM, Falco FJE, Helm II S, et al. Opioids in chronic noncancer pain: have we reached a boiling point yet? Pain Phys. 2014;17:E1–10.

Manchikanti L, Atluri S, Candido KD, Boswell MV, Simopoulos TT, Grider JS, et al. Zohydro™ approval by Food and Drug Administration: controversial or frightening? Pain Phys. 2014;17:E437–50.

Friedly J, Chan L, Deyo R. Increases in lumbosacral injections in the Medicare population: 1994 to 2001. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:1754–60.

Friedly J, Chan L, Deyo R. Geographic variation in epidural steroid injection use in Medicare patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1730–7.

Manchikanti L, Singh V, Falco FJE, Cash KA, Pampati V. Evaluation of lumbar facet joint nerve blocks in managing chronic low back pain: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial with a 2-year follow-up. Int J Med Sci. 2010;7:124–35.

Manchikanti L, Singh V, Falco FJE, Cash KA, Fellows B. Comparative outcomes of a 2-year follow-up of cervical medial branch blocks in management of chronic neck pain: a randomized, double-blind controlled trial. Pain Phys. 2010;13:437–50.

Manchikanti L, Singh V, Falco FJE, Cash KA, Pampati V, Fellows B. The role of thoracic medial branch blocks in managing chronic mid and upper back pain: a randomized, double-blind, active-control trial with a 2-year follow-up. Anesthesiol Res Pract. 2012;2012:585806.

Nath S, Nath CA, Pettersson K. Percutaneous lumbar zygapophysial (facet) joint neurotomy using radiofrequency current, in the management of chronic low back pain. A randomized double-blind trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33:1291–7.

Lord SM, Barnsley L, Wallis BJ, McDonald GJ, Bogduk N. Percutaneous radio-frequency neurotomy for chronic cervical zygapophyseal-joint pain. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1721–6.

Cohen SP, Strassels SA, Kurihara C, Crooks MT, Erdek MA, Forsythe A, et al. Outcome predictors for sacroiliac joint (lateral branch) radiofrequency denervation. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34:206–14.

Patel N, Gross A, Brown L, Gekht G. A randomized, placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy of lateral branch neurotomy for chronic sacroiliac joint pain. Pain Med. 2012;13:383–98.

Civelek E, Cansever T, Kabatas S, Kircelli A, Yilmaz C, Musluman M, et al. Comparison of effectiveness of facet joint injection and radiofrequency denervation in chronic low back pain. Turk Neurosurg. 2012;22:200–6.

Tekin I, Mirzai H, Ok G, Erbuyun K, Vatansever D. A comparison of conventional and pulsed radiofrequency denervation in the treatment of chronic facet joint pain. Clin J Pain. 2007;23:524–9.

van Wijk RM, Geurts JW, Wynne HJ, Hammink E, Buskens E, Lousberg R, et al. Radiofrequency denervation of lumbar facet joints in the treatment of chronic low back pain: a randomized, double-blind, sham lesion-controlled trial. Clin J Pain. 2005;21:335–44.

van Kleef M, Barendse GA, Kessels A, Voets HM, Weber WE, de Lange S. Randomized trial of radiofrequency lumbar facet denervation for chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24:1937–42.

Lakemeier S, Lind M, Schultz W, Fuchs-Winkelmann S, Timmesfeld N, Foelsch C, et al. A comparison of intraarticular lumbar facet joint steroid injections and lumbar facet joint radiofrequency denervation in the treatment of low back pain: a randomized, controlled, double-blind trial. Anesth Analg. 2013;117:228–35.

Furlan AD, Pennick V, Bombardier C, van Tulder M, Editorial Board, Cochrane Back Review Group. 2009 updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:1929–41.

Manchikanti L, Hirsch JA, Cohen SP, Heavner JE, Falco FJE, Diwan S, et al. Assessment of methodologic quality of randomized trials of interventional techniques: development of an interventional pain management specific instrument. Pain Phys. 2014;17:E263–90.

Manchikanti L, Hirsch JA, Heavner JE, Cohen SP, Benyamin RM, Sehgal N, et al. Development of an interventional pain management specific instrument for methodologic quality assessment of nonrandomized studies of interventional techniques. Pain Phys. 2014;17:E291–317.

Manchikanti L, Falco FJE, Benyamin RM, Kaye AD, Boswell MV, Hirsch JA. A modified approach to grading of evidence. Pain Phys. 2014;17:E319–25.

Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Damron KS. The role of placebo and nocebo effects of perioperative administration of sedatives and opioids in interventional pain management. Pain Phys. 2005;8:349–55.

Manchikanti L, Giordano J, Fellows B, Hirsch JA. Placebo and nocebo in interventional pain management: a friend or a foe—or simply foes? Pain Phys. 2011;14:E157–75.

Bingel U, Placebo Competence Team. Avoiding nocebo effects to optimize treatment outcome. JAMA. 2014;312:693–4.

Colloca L, Finniss D. Nocebo effects, patient-clinician communication, and therapeutic outcomes. JAMA. 2012;307:567–8.

Testa M, Rossettini G. Enhance placebo, avoid nocebo: how contextual factors affect physiotherapy outcomes. Man Ther. 2016;24:65–74.

Bartley H, Faasse K, Horne R, Petrie KJ. You can’t always get what you want: the influence of choice on nocebo and placebo responding. Ann Behav Med. 2016;50:445–51.

Vase L, Vollert J, Finnerup NB, Miao X, Atkinson G, Marshall S, et al. Predictors of the placebo analgesia response in randomized controlled trials of chronic pain: a meta-analysis of the individual data from nine industrially sponsored trials. Pain. 2015;156:1795–802.

Manchikanti L, Knezevic NN, Boswell MV, Kaye AD, Hirsch JA. Epidural injections for lumbar radiculopathy and spinal stenosis: a comparative systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Phys. 2016;16:E365–410. This manuscript compares in detail the systematic review and meta-analysis performed by Chou et al. for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) that was published in Annals of Internal Medicine. This manuscript shows the deficiencies in the design, methodologic quality assessment, and grading of evidence in the manuscript by Chou et al. and how their conclusions lack clinical relevance.

Boswell MV, Manchikanti L. Appropriate design and methodologic quality assessment, clinically relevant outcomes are essential to determine the role of epidural corticosteroid injections. Commentary RE: Chou R, Hashimoto R, Friedly J, et al. Epidural corticosteroid injections for radiculopathy and spinal stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:373–381. Evid Based Med. 2016;21:89.

Friedly JL, Comstock BA, Turner JA, Heagerty PJ, Deyo RA, Sullivan SD, et al. A randomized trial of epidural glucocorticoid injections for spinal stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:11–21.

Manchikanti L, Candido KD, Kaye AD, Boswell MV, Benyamin RM, Falco FJE, et al. Randomized trial of epidural injections for spinal stenosis published in the New England Journal of Medicine: further confusion without clarification. Pain Phys. 2014;17:E475–88.

Kaye AD, Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Atluri S, Bakshi S, Benyamin R, et al. Efficacy of epidural injections in managing chronic spinal pain: a best evidence synthesis. Pain Phys. 2015;18:E939–1004.

Manchikanti L, Benyamin RM, Falco FJ, Kaye AD, Hirsch JA. Do epidural injections provide short- and long-term relief for lumbar disc herniation? A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:1940–56.

Manchikanti L, Nampiaparampil DE, Manchikanti KN, Falco FJE, Singh V, Benyamin RM, et al. Comparison of the efficacy of saline, local anesthetics, and steroids in epidural and facet joint injections for the management of spinal pain: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Surg Neurol Int. 2015;6:S194–235. This manuscript shows the comparative efficacy of local anesthetics with or without steroids in managing chronic spinal pain with epidural and facet joint injections. This manuscript showed overwhelmingly the effectiveness of bupivacaine alone in managing facet joint pain with no significant difference when steroids were added.

Manchikanti L, Kaye AD, Manchikanti KN, Boswell MV, Pampati V, Hirsch JA. Efficacy of epidural injections in the treatment of lumbar central spinal stenosis: a systematic review. Anesth Pain Med. 2015;5:e23139.

Manchikanti L, Singh V, Pampati V, Smith HS, Hirsch JA. Analysis of growth of interventional techniques in managing chronic pain in Medicare population: a 10-year evaluation from 1997 to 2006. Pain Phys. 2009;12:9–34.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Laurie Swick, BS, for manuscript review and Tonie M. Hatton and Diane E. Neihoff, transcriptionists, for their assistance in preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Laxmaiah Manchikanti declares to have provided limited consulting services to Semnur Pharmaceuticals, Incorporated, which is developing nonparticulate steroids.

Joshua A. Hirsch declares he is a consultant for Medtronic and declares personal fees for teaching a single course for Carefusion.

Vidyasagar Pampati and Mark V. Boswell declare no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Disclaimer

There was no external financial support. The support was from the first author’s practice.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Other Pain

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 110 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Manchikanti, L., Hirsch, J.A., Pampati, V. et al. Utilization of Facet Joint and Sacroiliac Joint Interventions in Medicare Population from 2000 to 2014: Explosive Growth Continues!. Curr Pain Headache Rep 20, 58 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-016-0588-2

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-016-0588-2