Abstract

Purpose of Review

Supervised drug consumption facilities (SCFs) have increasingly been implemented in response to public health and public order concerns associated with illicit drug use. We systematically reviewed the literature investigating the health and community impacts of SCFs.

Recent Findings

Consistent evidence demonstrates that SCFs mitigate overdose-related harms and unsafe drug use behaviours, as well as facilitate uptake of addiction treatment and other health services among people who use drugs (PWUD). Further, SCFs have been associated with improvements in public order without increasing drug-related crime. SCFs have also been shown to be cost-effective.

Summary

This systematic review suggests that SCFs are effectively meeting their primary public health and order objectives and therefore supports their role within a continuum of services for PWUD. Additional studies are needed to better understand the potential long-term health impacts of SCFs and how innovations in SCF programming may help to optimize the effectiveness of this intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Illicit drug use remains a major global public health concern and, in particular, is a key driver of HIV/AIDS and overdose epidemics [1,2,3,4]. Public drug use and public disposal of syringes are also community concerns in various settings, particularly in inner-city neighbourhoods [5]. In an effort to mitigate these challenges, supervised drug consumption facilities (SCFs) have been established in a number of cities worldwide [6•, 7•]. SCFs are healthcare facilities that provide sterile equipment and a safe and hygienic space for people who use drugs (PWUD) to consume pre-obtained illicit drugs under the supervision of nurses or other trained staff [7•]. SCFs are also referred to as drug consumption rooms and include supervised injection facilities (SIFs), which accommodate people who inject drugs (PWID), and supervised inhalation rooms (SIRs), which accommodate people who inhale drugs.

Although SCFs vary in design and operational procedures, the aims of SCFs are similar across sites [8, 9]. Specifically, the primary objectives of SCFs are to attract higher-risk PWUD and to offer the following public health and public order benefits: (1) reduce the harms associated with illicit drug use, including fatal overdose and infectious disease transmission; (2) connect PWUD with addiction treatment and other health and social services; and (3) reduce public order and safety problems associated with illicit drug use (e.g. public drug use, publicly-discarded syringes) [8, 9]. Since the first legally-sanctioned SCF opened in Berne, Switzerland in 1986 [7•], these facilities have increasingly been implemented and there are now more than 90 SCFs operating internationally [7•]. Nonetheless, concerns regarding the potential negative consequences of SCFs, including that these may promote drug use and crime, have made these facilities difficult to implement [8, 10, 11].

In recent years, the evidence specific to SCFs has grown considerably. However, previous reviews of this evidence have suffered from some notable methodological shortcomings, including employment of search strategies that were narrow in scope, application of broad study eligibility criteria that resulted in the inclusion of low-quality evidence, and/or lack of assessment of the quality of included evidence [6•, 8, 12]. Guided by the primary health and public order objectives of SCFs noted above, the purpose of the present study was to systematically review existing quantitative research on the health and community outcomes associated with SCFs. In addition, we sought to identify underexplored opportunities to inform future research specific to SCFs.

Methods

Search Strategy

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for systematic reviews (see Supplement 1) [13], we searched for SCF studies published in the following databases from inception to May 01, 2017: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science, PsychINFO, Google Scholar and CINAHL. Search terms were combined using appropriate Boolean operators and included the subject heading terms or key words related to SCFs (see Supplement 2 for a detailed search strategy). In addition to electronic databases, we searched the reference lists of retrieved studies, relevant conference proceedings and key journals in the area of addiction. We also conducted a comprehensive grey literature search (i.e. dissertations, reports). We did not restrict our search to a specific language.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The population, interventions, comparisons, outcomes and study designs considered in the review are listed in Table 1.

Study Screening, Data Extraction and Analysis

Title and abstract screening were conducted to identify studies that potentially met our inclusion criteria. Full texts of all potentially eligible studies were retrieved (MCK) and independently assessed for eligibility by two authors (MCK and MK). Disagreements between the authors were resolved through discussion. Extracted data on study-specific information were summarized narratively and in a structured table.

Quality Assessment

Quality assessment of cohort, cross-sectional and pre-post studies was conducted using the 14-item National Heart, Blood and Lung Institute (NHBLI) Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies [14] or the 12-item NHBLI Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After (Pre-Post) Studies [15], as appropriate. Quality assessment for cost-effectiveness studies was completed using the Joanna Briggs Institute’s Critical Appraisal Checklist for Economic Evaluations [16].

Results

As shown in Fig. 1, database searching yielded 1476 records, and hand searching yielded an additional 85 records to account for a total of 1469 potentially eligible studies after duplicate removal. Of these, 1128 records were excluded through title and abstract screenings. Assessment of the full text of the remaining 341 records resulted in the exclusion of an additional 294 studies. In total, 47 studies published between 2003 and 2017 met the eligibility criteria and were included in the review.

Flowchart of record screening and selection process. From [17]

Summary of Included Studies

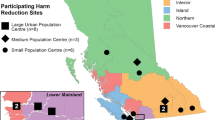

Of the 47 included studies, the majority (n = 28) were conducted in Vancouver, Canada; ten were conducted in Sydney, Australia; and the remaining studies were conducted in the following European countries: Germany (n = 4), Denmark (n = 2), Spain (n = 2) and the Netherlands (n = 1). Seventeen studies employed prospective cohort designs, while the remaining studies employed times series or pre-post ecological (n = 10), cross-sectional (n = 9), mathematical simulation (n = 8) or series cross-sectional (n = 3) designs. Study quality scores are presented in Table S1–3. Overall, most studies had good methodological quality. Additional study-specific information (including study location, design, participant characteristics, exposure(s), outcome(s), and main findings) is presented in Table 2.

Objective 1: to Reduce the Harms Associated with Illicit Drug Use

-

1a.

Overdose-Related Morbidity and Mortality

Of eight studies examining overdose-related outcomes [18, 20, 21, 29, 36, 37, 49, 52], six suggested a protective effect of SCFs [18, 20, 29, 37, 49, 52]. For example, the establishment of Insite, Vancouver’s largest SIF, was associated with a 35% reduction in overdose deaths in the immediate vicinity of the SIF after the facility opened, compared to a 9% reduction in the rest of the city [52]. An earlier simulation study found that Insite averts an estimated 1.9 to 11.7 overdose deaths per year [37]. Similar findings have been observed in ecological and simulation studies conducted in Germany [18, 20]. Likewise, the establishment of the SIF in Sydney, Australia, was associated with declines in opioid poisoning emergency department presentations [29] and ambulance attendances at opioid-related overdoses near the SIF [49]. However, there were no statistically significant changes in the number of opioid-related deaths in the neighbourhood of the SIF compared to the rest of the state after the SIF opened [29]. Another Sydney study found that frequent SIF clients were more likely to experience an overdose within the SIF, likely due to their greater exposure time at the facility [21]. Finally, a study conducted in Vancouver examined the association between frequent SIF use and recent non-fatal overdose among PWID and produced null results [36].

-

1b.

Drug-Related Risk Behaviours

Nine studies evaluated the relationship between SCFs and levels of drug use or drug-related behaviours that may increase risk of infectious disease transmission and other harms [23, 25, 26, 28, 35, 40, 50, 58, 62]. Of these, four studies examined the relationship between SCF use and syringe sharing [23, 25, 40, 50], three of which provided evidence of an inverse association [23, 25, 40]. For example, a cross-sectional study of PWID in Vancouver found that regular SIF users were 70% less likely to report borrowing or lending used syringes, despite the fact that SIF users and non-users reported similar levels of syringe sharing prior to the establishment of the SIF in retrospective analyses [23]. Two studies (conducted in Demark and Vancouver) demonstrated an association between SCF use and decreased likelihood of other types of unsafe injection behaviours, including reusing of syringes, injecting outdoors, and rushing injections, as well as an increased likelihood of safe behaviours such as using clean water for injecting, cooking or filtering drugs, and safely disposing syringes [31, 58]. Only one small German study with a short follow-up period found no evidence of an association between SCF use and injection-related risks (e.g. public drug use; equipment sharing) [50]. This study also found that SIF use was not significantly associated with development of cutaneous injection-related infections, as was found in a prospective study conducted in Vancouver [35, 50]. With regard to drug use patterns, a study undertaken in Vancouver found no substantial changes in rates of relapse into injection drug use, ceasing injection, ceasing binge drug use, or participation in methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) after the SIF opened among a prospective cohort of PWUD [26]. As well, another prospective Vancouver study found that the rate of recent initiation into injection drug use among SIF users was markedly lower than the estimated background community-level rate of injection initiation [28].

-

1c.

Other Health and Social Outcomes

Two prospective cohort studies from Vancouver examined health or social outcomes among PWUD other than overdose-related outcomes or drug-related behaviours [38, 41]. One of these found that SIF use was not significantly associated with employment in multivariable analyses [38]. The other study found that both use of SIF services and time since recruitment from the SIF were independently and positively associated with consistent condom use among PWID with regular but not casual partners [41].

Objective 2: to Connect PWUD with Addiction Treatment and Other Health and Social Services

-

2a.

Addiction Treatment

Four studies provided evidence of a positive association between SCF use and uptake of addiction treatment [27, 32, 34, 51]. For example, a prospective study of PWID in Vancouver found that at least weekly SIF use and contact with a SIF addictions counsellor were associated with more rapid entry into detoxification programmes [27]. A follow-up study demonstrated that rates of entry into detoxification programmes among SIF users increased by more than 30% in the year after compared to the year before the SIF was established [32]. Further, this study found that such enrolment in a detoxification programme was associated with earlier entry into MMT and other forms of addiction treatment, as well as subsequent declines in injections at the SIF [32]. An additional prospective study in Vancouver found that at least weekly SIF use was positively associated with enrolment in addiction treatment, which in turn was associated with an increased likelihood of injection cessation [51]. Similarly, a prospective study of PWID in Sydney found that frequent SIF use was positively associated with referral to addiction treatment, although analyses with addiction treatment uptake as the outcome produced null results [34]. In addition, a sole study examining barriers to treatment found that frequent SIF use was not significantly associated with inability to access addiction treatment among SIF users in Vancouver [47].

-

2b.

Other Health and Social Services

Six studies examined the association between SCF use and utilization of health or social services other than addiction treatment [19, 39, 44, 46, 54, 60]. For instance, a recent multi-site cross-sectional study of SCF users in Denmark found that being advised to seek treatment for a medical condition by SCF staff was associated with an increased likelihood of receiving treatment [60]. Additionally, two separate prospective cohort studies of SIF users in Vancouver found that those referred to hospital by SIF nurses were more likely to access the emergency department and receive hospital care, respectively, for cutaneous injection-related infections [46, 54]. Further, the latter study also found that such referrals were associated with shorter durations of hospitalization [46]. Three studies (conducted in Canada, Germany and Denmark) demonstrated links between SCF use and utilization of education on safer drug use practices at SCFs [19, 39, 60], while the German study also found an association between frequent SCF use and greater likelihood of accessing syringe exchange services, medical services and counselling at the SCF [19]. Another study, conducted in three cities in the Netherlands, found that SCF users had a higher level of awareness but a similar prevalence of uptake of a hepatitis B vaccination programme compared to non-users [44].

Two additional studies examined health-related outcomes associated with programmes offered within SCFs [59, 61]. A recent Vancouver study of a pilot drug checking program offered within Insite found that SIF clients who checked their drugs and received a positive result for fentanyl (a powerful opioid associated with elevated overdose risk) were more likely to reduce their doses but not to dispose of their drugs compared to those receiving negative results [61]. Another study found that the implementation of a smoking cessation organizational change intervention in the Sydney SIF was associated with an increased likelihood of receiving smoking cessation care among SIF clients [59].

Objective 3: to Reduce the Public Order and Safety Problems Associated with Injection Drug Use

-

3a.

Public Drug Use and Publicly Discarded Injection Equipment

Five studies have demonstrated the role of SCFs in addressing public disorder associated with illicit drug use [5, 24, 29, 30, 56]. An ecological study employing a prospective data collection protocol found that the establishment of a SIF in Vancouver was associated with reductions in the number of people injecting drugs in public, publicly discarded syringes and injection-related litter, independent of changes in police presence and weather patterns [5]. Similarly, there were observed declines in publicly-discarded syringes and public injection in the neighbourhood of the SIF in Sydney after the facility opened [29, 30]. There were also increases in the proportion of residents who agreed with positive statements regarding SIFs (including that these reduce public injection and public disposal of used syringes), although opinions were mixed among business owners [24]. Another study found that the opening of SCFs in Barcelona, Spain, was associated with a significant reduction in the number of publicly-discarded syringes collected by local services [56].

-

3b.

Crime

Six studies examined the association between SCF operation and drug-related crime [11, 22, 42, 45, 30, 55]. Of these, four were conducted in Sydney and found no changes in police-recorded thefts or robbery incidents, drug possession, drug dealing or illicit drug offences in the neighbourhood of the SIF after the facility was established [22, 45, 30, 55]. Similar results have been observed in Vancouver. For example, a before and after study of local crime statistics found no increases in incidents of drug trafficking or assaults/robbery in the neighbourhood of the SIF after the facility opened [11]. In addition, a prospective cohort study of PWID in Vancouver demonstrated that frequent SIF use was not associated with recent incarceration in multivariable analyses [42].

-

3c.

Cost-Effectiveness

A total of six studies have evaluated the cost-effectiveness of SCFs, all of which were conducted in Vancouver [33, 43, 48, 53, 57, 63]. Five studies examined the economic impacts of Insite and found it to be cost-effective [33, 43, 48, 53, 63]. For example, a simulation study estimated that the SIF provides an excess of $CAD 6 million per year (due to averted overdose deaths and incident HIV cases) after considering the facility’s annual operating costs [43]. Others have provided more conservative estimates, including a study estimating that the prevention of incident HIV cases and overdose deaths by the SIF provides an excess of $CAD 200,000–400,000 per year [53]. Additionally, a recent study of the cost-effectiveness of an unsanctioned peer-run SIR found that the facility saved an annual average of $CAD 1.8 million due to the prevention of incident cases of hepatitis C (HCV) infection [57].

Discussion

In the present systematic review, we identified consistent, methodologically sound evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of SCFs in achieving their primary health and public order objectives. Further, the available evidence does not support concerns regarding the potential negative consequences of establishing SCFs, including that these promote drug use or attract crime.

The prevention of drug-related overdose fatalities represents a significant public health challenge in many settings, particularly in North America, where opioid-related overdose deaths have reached epidemic levels and become a leading cause of accidental death in many jurisdictions [4]. Given that early, rapid and well-equipped overdose intervention is available within SCFs [8], and that these facilities have been shown to attract PWUD who possess risk factors for overdose (e.g. homelessness, high-intensity drug use) [8, 19, 21, 64,65,66], the broader expansion of SCFs in settings contending with overdose epidemics may afford opportunities to mitigate overdose-related morbidity and mortality. Indeed, compelling ecological and simulation studies included in this review have demonstrated the contributions of SCFs to reductions in overdose-related deaths, emergency department presentations and ambulance attendances [18, 20, 29, 37, 49, 52]. It is also noteworthy that despite the millions of injections that have occurred within SCFs internationally over the past three decades, not a single overdose death has been recorded within a SCF [6•, 8]. In addition, although preventing non-fatal overdose is not a key objective of SCFs, frequent SCF use has not been found to increase non-fatal overdose risk, which challenges the contention that these facilities promote riskier drug use practices (e.g. taking higher doses) associated with overdose [36]. Although one report included in this review observed non-significant declines in opioid-related deaths in Sydney after the SCF was established, the authors note that this study was likely underpowered [29].

As described elsewhere [8, 20], methodological challenges have impeded efforts to examine the impact of SCFs on the incidence of infectious diseases such as HIV and HCV. However, the studies assessed herein indicate positive impacts of SCFs on reducing unsafe injection practices associated with infectious disease transmission among higher-risk PWUD. For example, several studies have demonstrated associations between SCF use and reductions in syringe sharing [23, 25, 40], with a previous meta-analysis of three studies undertaken in Canada and Spain providing a pooled estimate of a 70% decreased likelihood of syringe sharing among SCF users [67]. Studies also suggest that SCFs contribute to declines in other unsafe injection practices such as reusing syringes, injecting outdoors or rushed injecting [31, 58], as has been found in descriptive studies of SCFs that were ineligible for this review [18, 68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79]. In addition to the provision of sterile injection equipment on site, there are several other mechanisms through which SCFs may reduce such behaviours. For example, SCFs often become a key source of sterile syringes for external use [80], which is notable given the well-documented impact of syringe exchange services in reducing risk of HIV and HCV transmission [81, 82]. Moreover, SCFs have been shown to increase access to safer injection education [19, 39, 60] and to decrease the need to rush injections due to fear of arrest [80]. Collectively, these findings provide strong evidence to support the expansion of SCFs as an infectious disease prevention strategy.

While concerns persist that SCFs may increase illicit drug use and discourage PWUD from seeking addiction treatment, such concerns are not supported by existing evidence. Indeed, the establishment of SCFs has not significantly altered community drug use patterns such as rates of injection initiation, relapse or cessation [26, 28]. Further, several studies demonstrate the role of SCFs in facilitating entry into addiction treatment programmes [27, 32, 34, 51] and subsequent injection cessation and/or reduced injecting at SCFs [32, 51]. Thus, these facilities appear to support rather than undermine the goals of addiction treatment.

In addition to addiction treatment, the research assessed in this review also suggests that SCFs provide opportunities for PWUD to access co-located services, including nursing, counselling and syringe exchange services [19, 44, 59,60,61], while also facilitating critical early medical intervention for the treatment of complex conditions such as cutaneous injection-related infections [19, 46, 54, 60]. Similarly, descriptive studies have found that SCFs may help to connect PWUD with other on-site services, including basic supportive services (e.g. food, personal care facilities), HIV testing, mental health care and naloxone training and distribution programmes [9, 83]. Further, the integration of SCFs and other low-threshold services into existing HIV/AIDS healthcare programmes has been shown to improve access to and engagement with HIV treatment and care among PWUD [84,85,86]. Recent qualitative work has provided insights into how SCFs foster a supportive and welcoming environment characterized by social acceptance and belonging in which PWUD feel comfortable engaging with SCF staff regarding health needs [86, 87]. Thus, although PWUD are known to commonly experience barriers in accessing conventional healthcare services [88, 89], the available data suggests that SCFs may help to mitigate such barriers in mediating access to a range of internal and external health and social resources for higher-risk drug-using populations.

Studies assessed in this review also indicate that SCFs are largely successful in achieving their objective of reducing public disorder associated with illicit drug use through declines in public injection and discarded drug use-related paraphernalia [5, 29, 30, 56]. These findings are consistent with those observed in descriptive studies showing declines in self-reported public drug use among SCF users [18, 29, 74, 77, 78]. Further, as has been found in descriptive studies undertaken in the Netherlands and Switzerland [72, 90,91,92], the implementation of SCFs in Vancouver and Sydney did not appear to contribute to increases in drug dealing or drug-related crime [11, 22, 30, 45, 55]. Additionally, there is some evidence from Sydney to suggest increasing public acceptance and support of these facilities over time, although support was somewhat inconsistent among business owners [24]. This largely aligns with descriptive work conducted elsewhere suggesting mixed support in terms of public opinion of SCFs [9, 93], but that this tends to increase with time [8, 9, 20]. Finally, despite not being an explicit objective, economic evaluations undertaken in Vancouver indicate that SCFs also offer an additional public benefit of reducing the burden of costs on the public healthcare system [33, 43, 48, 53, 57, 63].

Overall, high-quality scientific evidence derived from the observational and simulation studies included in this review demonstrates the effectiveness of SCFs in meeting their primary public health and order objectives. Although randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are typically defined as the ‘gold standard’ for yielding level-one evidence on the effectiveness of a given intervention, it should be noted that RCTs of SCFs have been deemed unethical due to a lack of clinical equipoise and therefore have not been conducted [8, 94, 95]. However, reliance on hierarchies of evidence to guide public heath decision making has been contested in recent years [96,97,98]. Indeed, there has been growing acknowledgment that, like observational studies, RCTs often suffer from notable methodological weaknesses, including limited external validity, and that while RCTs may provide evidence that effectively serves the needs of clinical medicine, this is not necessarily the case in the realm of public policy [96, 98]. This is particularly relevant to decisions concerning complex public health interventions, as evidence of effectiveness in ‘real-world’ contexts and attention to considerations such as health equity and human rights may be of equal or greater relevance to public health goals than controlled study of intervention efficacy [98]. Further, assigned level of evidence is not necessarily indicative of methodological quality, and therefore well-designed observational research can arguably provide a level of evidence that meets or exceeds that derived from RCTs [96,97,98]. Thus, given that it will not be possible to obtain evidence from RCTs on SCFs, decisions regarding the implementation of these facilities should instead be informed by the best available evidence derived from scientifically-viable studies, which clearly demonstrates the positive impacts of SCFs in improving public order and advancing the health and human rights of socially marginalized PWUD.

Directions for Future Research

Although the available evidence suggests that SIFs improve the health of PWUD and reduce community concerns associated with illicit drug use, several important research opportunities remain unexplored. First, despite evidence of the short- and medium-term health impacts of SCFs, rigorous research on the long-term impacts of SCFs on the health of PWUD is lacking. For example, while previous work has found that SCF use increases the likelihood of short-term injection cessation [51], it is not known if SCF use has an impact on sustained injection cessation or cessation of drug use altogether. An additional area of evaluation that has not received adequate attention is the impact of SCFs on hospitalization among PWUD. Although previous research indicates that referral to hospital by SCF nurses facilitates hospital treatment for cutaneous injection-related infections [46], little is known about how SCF use might affect acute hospital bed use for other conditions.

There is also a need for research to evaluate SCF programming that aims to improve their responsiveness to the needs of vulnerable and underserved subpopulations of PWUD. For example, with the exception of SCFs operating in Geneva and Barcelona [99], SCFs in most settings are legally prohibited from accommodating individuals who require manual assistance with injections, despite the fact that this subpopulation accounts for an estimated one third of PWID [100], is comprised largely of women and people with disabilities [100] and is disproportionally vulnerable to an array of serious harms including overdose, HIV infection and violence [101,102,103]. A qualitative evaluation of an unsanctioned, peer-run SCF in Vancouver that offered manual assistance with injections found that the provision of this service in a regulated environment helped to reduce risk for the above-mentioned harms [104]. Nonetheless, further research on the potential benefits of offering assisted injection within SCFs may help to strengthen the case for legal reforms to allow for the wider adoption of this practice. In addition, although SCFs have previously been shown to provide protection from street-based drug scene violence for some women PWUD [105], other women may avoid SCFs due to perceived threats of violence [106]. In an effort to address such concerns, women-only SCFs have been implemented in several settings, including in Hamburg, Germany, and another is planned to open in Vancouver, Canada [107, 108]. While research undertaken in Hamburg found that the overwhelming majority of women-only SCF clients felt safer and more comfortable using drugs and approaching staff at this SCF [108], studies should further explore the ability of this form of tailored service to engage and support the health of structurally vulnerable drug-using women.

An additional research opportunity is to evaluate the health and social impacts of SIRs, which accommodate people who inhale drugs. Although SIRs are presently operating in some European cities [108] and recent qualitative research indicates that these facilities have potential to promote safer smoking practices and reduce health-related harms [60, 109•, 110], the health and community outcomes specific to SIRs have not been thoroughly evaluated. As SIRs remain underutilized in many settings [107, 108], further inquiry in this area may provide critical information to inform the broader implementation of these facilities.

Another notable knowledge gap concerns the role and impacts of novel SCF models, including those integrated into existing healthcare and social services. For instance, although there is evidence to suggest a high level of willingness to use an in-hospital SCF among PWUD [111] and a SCF recently opened in a hospital in Paris, France [112], few studies have investigated the effectiveness of this type of SCF model. However, recent qualitative research suggests that the provision of in-hospital SCFs could reduce instances of patients leaving hospital against medical advice, promote culturally safe care and prevent adverse outcomes associated with in-hospital drug use among PWUD [113]. Future studies should also investigate if the benefits of stand-alone SCFs will extend to SCFs integrated into existing shelters, supportive housing and community organizations that serve PWUD, as research on such integrated SCF services is lacking. A related recommendation is to further examine the uptake and potential outcomes associated with services co-located with SCFs, including on-site addiction treatment and low-threshold housing [114]. As well, given the limited geographic coverage of fixed-site SCFs [52, 64], studies should evaluate how the implementation of mobile SCFs might improve the responsiveness of SCF programming to the needs of PWUD, particularly those who reside in settings with geographically dispersed drug scenes or who experience social-structural barriers to attending fixed SCFs (e.g. sex workers working in remote locations; women who avoid SCFs due to previous experiences of violence) [106, 107, 115].

A final recommendation is the continued assessment of peer-run SCFs, which are prohibited in many settings despite evidence of their ability to engage and reduce harms among PWUD who may encounter social-structural and programmatic barriers in accessing SCFs operated by healthcare professionals [9, 104, 107, 110]. Specifically, future studies should seek to better characterize preferences for, engagement with and outcomes associated with peer-run SCF models, as this may help to further elucidate the role of these facilities in complementing or extending the reach of conventional SCF programmes.

Limitations

A number of limitations common to observational studies apply to many of the studies included in this review. First, it is possible that the findings of the studies assessed herein are explained by residual confounding. In addition, most studies relied on non-random samples of PWUD in resource-rich settings and therefore findings may not be generalizable to other contexts. Further, as previous work has indicated that SCFs attract socially marginalized and higher-risk PWUD [8, 19, 21, 64,65,66], observed measures of the health benefits of SCF use may be biased towards the null. Finally, a limitation of this review is that despite our comprehensive search strategy, it is possible that we neglected to include some relevant literature, particularly non-English literature, not indexed in the databases searched for this review.

Conclusions

In summary, while SCFs remain under-utilized in many settings worldwide, high-quality scientific evidence suggests that these effectively achieve their primary public health and order objectives with a lack of adverse impacts, and therefore supports their role as part of a continuum of services for PWUD. However, further studies are needed to better understand the potential long-term health impacts of these facilities. In addition, future research should continue to investigate innovations in SCF models and programming, including efforts to tailor SCFs to the needs of vulnerable subpopulations of PWUD, in order to optimize the effectiveness and extend the reach and coverage of this form of harm reduction intervention.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

UNAIDS. UNAIDS global report [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2017 May 30]. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en_1.pdf

Karon JM, Fleming PL, Steketee RW, De Cock KM. HIV in the United States at the turn of the century: an epidemic in transition. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(7):1060–8.

Doherty MC, Garfein RS, Vlahov D, Junge B, Rathouz PJ, Galai N, et al. Discarded needles do not increase soon after the opening of a needle exchange program. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(8):730–7.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Vital Statistics System, Mortality File. Number and age-adjusted rates of drug-poisoning deaths involving opioid analgesics and heroin: United States, 2000–2014 [Internet]. Atlanta: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015 [cited 2017 Apr 7]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/health_policy/AADR_drug_poisoning_involving_OA_Heroin_US_2000-2014.pdf

Wood E, Kerr T, Small W, Li K, Marsh DC, Montaner JSG, et al. Changes in public order after the opening of a medically supervised safer injecting facility for illicit injection drug users. Can Med Assoc J. 2004;171(7):731–4.

• Potier C, Laprévote V, Dubois-Arber F, Cottencin O, Rolland B. Supervised injection services: what has been demonstrated? A systematic literature review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;145:48–68. This systematic review includes descriptive, qualitative and feasibility studies specific to supervised injection facilities not included in the present study.

• European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). Drug consumption rooms: an overview of provision and evidence [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2017 May 12]. Available from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/topics/pods/drug-consumption-rooms. This report provides a recent overview of the global distribution of supervised consumption facilities and a summary of the evidence on effectiveness.

Hedrich D, Kerr T, Dubois-Arber F. Drug consumption facilities in Europe and beyond. In: Rhodes T, Hedrich D, editors. Harm reduction: evidence, impacts, and challenges. Lisbon: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction; 2010. p. 306–31.

Woods S. Drug consumption rooms in Europe: organizational overview [Internet]. Peacey J, Geise M, editors. European Harm Reduction Network. Amsterdam: Regenboog Groep; 2014 [cited 2017 Jun 14]. Available from: http://www.eurohrn.eu/images/stories/pdf/publications/dcr_in_europe.pdf

Kennedy MC, Kerr T. Overdose prevention in the United States: a call for supervised injection sites. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(1):42–3.

Wood E, Tyndall MW, Lai C, Montaner JS, Kerr T. Impact of a medically supervised safer injecting facility on drug dealing and other drug-related crime. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2006;1:13.

Rapid Response Service. Rapid response: what is the effectiveness of supervised injection services? [Internet]. Ontario HIV Treatment Network; 2014 [cited 2017 Jun 8]. Available from: http://www.ohtn.on.ca/Pages/Knowledge-Exchange/Rapid-Responses/Documents/RR83-Supervised-Injection-Effectiveness.pdf

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

National Heart, Blood and Lung Institute. Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2017 May 14]. Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/tools/cohort

National Heart, Blood and Lung Institute. Quality assessment tool for before-after (pre-post) studies. [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2017 May 14]. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/tools/before-after

Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Economic Evaluations. [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2017 May 14]. Available from: http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Poschadel S, Höger R, Schnitzler J, Schreckenberger J. Evaluation der Arbeit der Drogenkonsumräume in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Endbericht im Auftrag des Bundesministeriums für Gesundheit, Das Bundesministerium für Gesundheit und Soziale Sicherung (Schriftenreihe Bd 149). Baden-Baden: Nomos- Verlags-Gesellschaft; 2003.

Zurhold H, Degkwitz P, Verthein U, Haasen C. Drug consumption rooms in Hamburg, Germany: evaluation of the effects on harm reduction and the reduction of public nuisance. J Drug Issues. 2003;33(3):663–88.

Hedrich D. European report on drug consumption rooms [Internet]. Lisbon: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction; 2004 [cited 2017 May 20]. Available from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/html.cfm/index54125EN.html

van Beek I, Kimber J, Dakin A, Gilmour S. The Sydney medically supervised injecting centre: reducing harm associated with heroin overdose. Crit Public Health. 2004;14(4):391–406.

Freeman K, Jones C, Weatherburn D, Rutter S, Spooner C, Donnelly N. The impact of the Sydney Medically Supervised Injecting Centre (MSIC) on crime. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2005;24(2):173–84.

Kerr T, Tyndall M, Li K, Montaner J, Wood E. Safer injection facility use and syringe sharing in injection drug users. Lancet. 2005;366(9482):316–8.

Thein H, Kimber J, Maher L, MacDonald M, Kaldor J. Public opinion towards supervised injecting centres and the Sydney Medically Supervised Injecting Centre. Int J Drug Policy. 2005;16(4):275–80.

Wood E, Tyndall MW, Stoltz J-A, Small W, Lloyd-Smith E, Zhang R. Factors associated with syringe sharing among users of a medically supervised safer injecting facility. Am J Infect Dis. 2005;1(1):50–4.

Kerr T, Stoltz J-A, Tyndall M, Li K, Zhang R, Montaner J, et al. Impact of a medically supervised safer injection facility on community drug use patterns: a before and after study. BMJ. 2006;332(7535):220–2.

Wood E, Tyndall MW, Zhang R, Stoltz J-A, Lai C, Montaner JSG, et al. Attendance at supervised injecting facilities and use of detoxification services. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(23):2512–4.

Kerr T, Tyndall M., Zhang R, Lai C, Montaner J., Wood E. Circumstances of first injection among illicit drug users accessing a medically supervised safer injection facility. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7).

NCHECR. Sydney Medically Supervised Injecting Centre evaluation report no. 4: evaluation of service operation and overdose-related events [Internet]. Sydney: National Centre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research, University of New South Wales; 2007 [cited 2017 Jun 7]. Available from: https://kirby.unsw.edu.au/report/sydney-medically-supervised-injecting-centre-msic-evaluation-report-4

Salmon A, Thein H, Kimber J, Kaldor J, Maher L. Five years on: what are the community perceptions of drug-related public amenity following the establishment of the Sydney Medically Supervised Injecting Centre? Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18(1):46–53.

Stoltz J-A, Wood E, Small W, Li K, Tyndall M, Montaner J, et al. Changes in injecting practices associated with the use of a medically supervised safer injection facility. J Public Health. 2007;29(1):35–9.

Wood E, Tyndall MW, Zhang R, Montaner JSG, Kerr T. Rate of detoxification service use and its impact among a cohort of supervised injecting facility users. Addiction. 2007;102(6):916–9.

Bayoumi AM, Zaric GS. The cost-effectiveness of Vancouver’s supervised injection facility. Can Med Assoc J. 2008;179(11):1143–51.

Kimber J, Kimber J, Mattick RP, Kimber J, Mattick RP, Kaldor J, et al. Process and predictors of drug treatment referral and referral uptake at the Sydney Medically Supervised Injecting Centre. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27(6):602–12.

Lloyd-Smith E, Wood E, Zhang R, Tyndall MW, Montaner JS, Kerr T. Risk factors for developing a cutaneous injection-related infection among injection drug users: a cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):405.

Milloy M-JS, Kerr T, Mathias R, Zhang R, Montaner JS, Tyndall M, et al. Non-fatal overdose among a cohort of active injection drug users recruited from a supervised injection facility. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34(4):499–509.

Milloy M-J, Kerr T, Tyndall M, Montaner J, Wood E. Estimated drug overdose deaths averted by North America’s first medically-supervised safer injection facility. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(10).

Richardson L, Wood E, Zhang R, Montaner J, Tyndall M, Kerr T. Employment among users of a medically supervised safer injection facility. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34(5):519–25.

Wood RA, Wood E, Lai C, Tyndall MW, Montaner JSG, Kerr T. Nurse-delivered safer injection education among a cohort of injection drug users: evidence from the evaluation of Vancouver’s supervised injection facility. Int J Drug Policy. 2008;19(3):183–8.

Bravo MJ, Royuela L, De la Fuente L, Brugal MT, Barrio G, Domingo-Salvany A, et al. Use of supervised injection facilities and injection risk behaviours among young drug injectors. Addiction. 2009;104(4):614–9.

Marshall BDL, Wood E, Zhang R, Tyndall MW, Montaner JSG, Kerr T. Condom use among injection drug users accessing a supervised injecting facility. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85(2):121–6.

Milloy M-J, Wood E, Tyndall M, Lai C, Montaner J, Kerr T. Recent incarceration and use of a supervised injection facility in Vancouver, Canada. Addict Res Theory. 2009;17(5):538–45.

Andresen M, Boyd N. A cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness analysis of Vancouver’s supervised injection facility. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21(1):70–6.

Baars JE, Boon BJF, Garretsen HFL, van de Mheen D. The reach of a free hepatitis B vaccination programme: results of a Dutch study among drug users. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21(3):247–50.

Fitzgerald J, Burgess M, Snowball L. Trends in property and illicit drug crime around the Medically Supervised Injecting Centre in Kings Cross: an update [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2017 May 27]. Available from: http://www.bocsar.nsw.gov.au/Documents/BB/bb51.pdf

Lloyd-Smith E, Wood E, Zhang R, Tyndall MW, Sheps S, Montaner JS, et al. Determinants of hospitalization for a cutaneous injection-related infection among injection drug users: a cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):327.

Milloy M-JS, Kerr T, Zhang R, Tyndall M, Montaner J, Wood E. Inability to access addiction treatment and risk of HIV infection among injection drug users recruited from a supervised injection facility. J Public Health. 2010;32(3):342–9.

Pinkerton S. Is Vancouver Canada’s supervised injection facility cost-saving? Addiction. 2010;105(8):1429–36.

Salmon AM, Van Beek I, Amin J, Kaldor J, Maher L. The impact of a supervised injecting facility on ambulance call-outs in Sydney, Australia. Addiction. 2010;105(4):676–83.

Scherbaum N, Specka M, Schifano F, Bombeck J, Marrziniak B. Longitudinal observation of a sample of German drug consumption facility clients. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45(1–2):176–89.

DeBeck K, Kerr T, Bird L, Zhang R, Marsh D, Tyndall M, et al. Injection drug use cessation and use of North America’s first medically supervised safer injecting facility. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;113(2–3):172–6.

Marshall BD, Milloy M-J, Wood E, Montaner JS, Kerr T. Reduction in overdose mortality after the opening of North America’s first medically supervised safer injecting facility: a retrospective population-based study. Lancet. 2011;377(9775):1429–37.

Pinkerton SD. How many HIV infections are prevented by Vancouver Canada’s supervised injection facility? Int J Drug Policy. 2011;22(3):179–83.

Lloyd-Smith E, Tyndall M, Zhang R, Grafstein E, Sheps S, Wood E, et al. Determinants of cutaneous injection-related infections among injection drug users at an emergency department. Open Infect Dis J. 2012;6

Donnelly N, Mahoney N. Trends in property and illicit drug crime around the Medically Supervised Injecting Centre in Kings Cross: 2012 update [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2017 May 27]. Available from: http://www.bocsar.nsw.gov.au/Documents/BB/bb90.pdf

Vecino C, Villalbi J, Guitart A, Espelt A, Bartroli M, Castellano Y, et al. Apertura de espacios de consumo higienico y actuaciones policiales en zonas con fuerte trafico de drogas. Evaluacion mediante el recuento de las jeringas abandonadas en el espacio publico [Safe injection rooms and police crackdowns in areas with heavy drug dealing. Evaluation by counting discarded syringes collected from the public space]. Adicciones. 2013;25(4):333–8.

Jozaghi E, Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users. A cost-benefit/cost-effectiveness analysis of an unsanctioned supervised smoking facility in the downtown eastside of Vancouver, Canada. Harm Reduct J. 2014;11(1):30.

Kinnard EN, Howe CJ, Kerr T, Skjødt Hass V, Marshall BD. Self-reported changes in drug use behaviors and syringe disposal methods following the opening of a supervised injecting facility in Copenhagen, Denmark. Harm Reduct J. 2014;11:29.

Skelton E, Bonevski B, Tzelepis F, Shakeshaft A, Guillaumier A, Wood W, et al. Addressing tobacco smoking in a medically supervised injecting center with an organizational change intervention: an acceptability study. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2016;12(Suppl. 6):13.

Toth EC, Tegner J, Lauridsen S, Kappel N. A cross-sectional national survey assessing self-reported drug intake behavior, contact with the primary sector and drug treatment among service users of Danish drug consumption rooms. Harm Reduct J. 2016;13:27.

Lysyshn M, Dohoo C, Forsting S, Kerr T, McNeil R. Evaluation of a fentanyl drug checking program for clients of a supervised injection site, Vancouver, Canada. In: 25th Harm Reduction International Conference Montreal, May 14–17 Abstract 188 [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://www.hri.global/abstracts/abstrct/188/print

Stoltz J-AM, Shannon K, Kerr T, Zhang R, Montaner JS, Wood E. Associations between childhood maltreatment and sex work in a cohort of drug-using youth. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(6):1214–21.

Andresen MA, Jozaghi E. The point of diminishing returns: an examination of expanding Vancouver’s Insite. Urban Stud. 2012;49(16):3531–44.

Wood E, Tyndall MW, Qui Z, Zhang R, Montaner JSG, Kerr T. Service uptake and characteristics of injection drug users utilizing North America’s first medically supervised safer injecting facility. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(5):770–3.

Wood E, Tyndall MW, Li K, Lloyd-Smith E, Small W, Montaner JSG, et al. Do supervised injecting facilities attract higher-risk injection drug users? Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(2):126–30.

Kimber J, MacDonald M, van Beek I, Kaldor J, Weatherburn D, Lapsley H, et al. The Sydney Medically Supervised Injecting Centre: client characteristics and predictors of frequent attendance during the first 12 months of operation. J Drug Issues. 2003;33(3):639–48.

Milloy M-J, Wood E. Emerging role of supervised injecting facilities in human immodeficiency virus prevention. Addiction. 2009;104(4):620–1.

Minder Nejedly M, Bürki CM. Monitoring HIV risk behaviours in a street agency with injection room in Switzerland. Berne: Medical Faculty of the University in Berne; 1999.

Reyes FV. 15 Jahre Fixerraum Bern. Auswirkungen auf soziale und medizinische Aspekte bei Drogenabhängigen. Berne: Medical Faculty of the University of Berne; 2003.

Ronco S, Spuler G, Coda P, Schöpfer R. Evaluation der Gassenzimmer I, II und III in Basel. Soz- Präventivmedizin. 1996;41(Supplement 1):S58–68.

Ronco C, Spuhler G, Kaiser R. Evaluation des “Aufenthalts- und Betreuungsraums für Drogenabhängige” in Luzern [Evaluation of a stay and care center for drug addicts in Lucerne]. Soz- Präventivmedizin. 1996;41(Supplement 1):S45–57.

Benninghoff F, Solai S, Huissoud T, Dubois-Arber F. Evaluation de Quai 9 “Espace d”acceuil et d’injection’ à Genéve: période 12/2001–12/2000, Raisons de santé 103. Lausanne: Institut universitaire de médecine sociale et préventive; 2003.

Benninghoff F, Geense R, Dubois-Arber F. Resultats de l’étude “La clientèle des structures à bas seuil d”accessibilité en Suisse. Lausanne: Institut universitaire de médecine sociale et préventive; 2001.

Benninghoff F, Dubois-Arber F. Résultats de l’étude de la clientèle du Cactus BIEL/BIENNE 2001. Lausanne: Institut universitaire de médecine sociale et préventive; 2002.

Solai S, Benninghoff F, Meystre-Agustoni G, Jeannin A, Dubois-Arber F. Evaluation de l’espace d’accueil et d’injection “Quai 9” à Genève: deuxième phase 2003. Lausanne: Institut universitaire de médecine sociale et préventive; 2004.

Jacob J, Rottman J, Stöver H. Entstehung und Praxis eines Gesundheitsraumangebotes für Drogenkonsumierende. Abschlußbericht der einjährigen Evaluation des “drop-in Fixpunkt”/Hannover. Oldenburg: Schriftenreihe Sucht- Drog, 2, BIS–Verlag, Universität Oldenburg; 1999.

van der Poel A, Barendregt C, van de Mheen D. Drug consumption rooms in Rotterdam: an explorative description. Eur Addict Res. 2003;9:94–100.

Zurhold H, Kreuzfeld N, Degkwitz P, Verthein U. Drogenkonsumräume. Gesundheitsförderung und Minderung öffentlicher Belastungen in europäischen Grossstädten. Freiburg: Lambertus; 2001.

Petrar S, Kerr T, Tyndall MW, Zhang R, Montaner JSG, Wood E. Injection drug users’ perceptions regarding use of a medically supervised safer injecting facility. Addict Behav. 2007;32(5):1088–93.

Kerr T, Small W, Moore D, Wood E. A micro-environmental intervention to reduce the harms associated with drug-related overdose: evidence from the evaluation of Vancouver’s safer injection facility. Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18(1):37–45.

Aspinall EJ, Nambiar D, Goldberg DJ, Hickman M, Weir A, Van Velzen E, et al. Are needle and syringe programmes associated with a reduction in HIV transmission among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(1):235–48.

Abdul-Quader AS, Feelemyer J, Modi S, Stein ES, Briceno A, Semaan S, et al. Effectiveness of structural-level needle/syringe programs to reduce HCV and HIV infection among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(9):2878–92.

Wood W. Distributing “take home” naloxone via Sydney medically supervised injecting centre: Where to from here? Drug Alcohol Rev. 2015;34:67.

Collins A, Parashar S, Hogg R, Fernando S, Worthington C, McDougall P, et al. Integrated HIV care and service engagement among people living with HIV who use drugs in a setting with a community-wide treatment as prevention initiative: a qualitative study in Vancouver, Canada. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1).

Ti L, Dong H, Kerr T, Turje R, Parashar S, Min J, et al. The effect of engagement in an HIV/AIDS integrated health programme on plasma HIV-1 RNA suppression among HIV-positive people who use illicit drugs: a marginal structural modelling analysis. HIV Med. 2017;18(8):580-586.

McNeil R, Dilley LB, Guirguis-Younger M, Hwang SW, Small W. Impact of supervised drug consumption services on access to and engagement with care at a palliative and supportive care facility for people living with HIV/AIDS: a qualitative study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(1).

Kappel N, Toth E, Tegner J, Lauridsen S. A qualitative study of how Danish drug consumption rooms influence health and well-being among people who use drugs. Harm Reduct J. 2016;13:20.

Meyer JP, Althoff AL, Altice FL. Optimizing care for HIV-infected people who use drugs: evidence-based approaches to overcoming healthcare disparities. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(9):1309–17.

Fairbairn N, Milloy M-J, Zhang R, Lai C, Grafstein E, Kerr T, et al. Emergency department utilization among a cohort of HIV-positive injecting drug users in a Canadian setting. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(2):236–43.

Linssen. Gebruiksruimten. Een systematisch overzicht van de voorziening en de effecten ervan. 2003.

Meijer G, de Jong A, Koeter M, Bielman B. Gebruik van de straat. Evaluatie gebruiksruimnte Binnenstad-Zuid Groningen. Groningen-Rotterdam: INTRAVAL; 2001.

Spreyermann C, Willen C. Evaluationsbericht Öffnung der Kontakt- und Anlaufstellen für risikoärmere Konsumformen. Evaluation der Inhalationsräume der Kontakt- und Anlaufstellen Selnau und Seilergraben der Ambulanten Drogenhilfe Zürich [Internet]. 2003 [cited 2017 May 27]. Available from: http://www.indro-online.de/zuerich.pdf

BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS. Evaluation of the supervised injection site: year one summary [Internet]. Vancouver: BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS; 2004 [cited 2017 May 27]. Available from: http://www.salledeconsommation.fr/_media/bc-centre-for-excellence-in-hiv-aids-evaluation-of-the-supervised-injection-site-year-one-summary-september-17-2004.pdf

Christie T, Wood E, Schechter MT, O’Shaughnessy MV. A comparison of the new Federal Guidelines regulating supervised injection site research in Canada and the Tri-Council Policy Statement on Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Human Subjects. Int J Drug Policy. 2004;15(1):66–73.

Maher APL, Maher APL, Salmon A, Maher APL, Salmon A. Supervised injecting facilities: how much evidence is enough? Drug Alcohol Rev. 2007;26(4):351–3.

Worrall J. Evidence: philosophy of science meets medicine. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16(2):356–62.

Burns PB, Rohrich RJ, Chung KC. The levels of evidence and their role in evidence-based medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(1):305–10.

Parkhurst JO, Abeysinghe S. What constitutes “good” evidence for public health and social policy-making? From hierarchies to appropriateness. Soc Epistemol. 2016;30(5–6):665–79.

Solai S, Dubois-Arber F, Benninghoff F, Benaroyo L. Ethical reflections emerging during the activity of a low threshold facility with supervised drug consumption room in Geneva, Switzerland. Int J Drug Policy. 2006;17(1):17–22.

Wood E, Spittal PM, Kerr T, Small W, Tyndall MW, O’Shaughnessy MV, et al. Requiring help injecting as a risk factor for HIV infection in the Vancouver epidemic: implications for HIV prevention. Can J Public Health Rev Can Santee Publique. 2003;94(5):355–9.

Fairbairn N, Small W, Van Borek N, Wood E, Kerr T. Social structural factors that shape assisted injecting practices among injection drug users in Vancouver. Canada: a qualitative study Harm Reduct J. 2010;7:20.

O’Connell JM, Kerr T, Li K, Tyndall MW, Hogg RS, Montaner JS, et al. Requiring help injecting independently predicts incident HIV infection among injection drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2005;40(1):83–8.

Kerr T, Fairbairn N, Tyndall M, Marsh D, Li K, Montaner J, et al. Predictors of non-fatal overdose among a cohort of polysubstance-using injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87(1):39–45.

McNeil R, Small W, Lampkin H, Shannon K, Kerr T. “People knew they could come here to get help”: an ethnographic study of assisted injection practices at a peer-run “unsanctioned” supervised drug consumption room in a Canadian setting. AIDS Behav. 2013;18(3):473–85.

Fairbairn N, Small W, Shannon K, Wood E, Kerr T. Seeking refuge from violence in street-based drug scenes: women’s experiences in North America’s first supervised injection facility. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(5):817–23.

McNeil R, Shannon K, Shaver L, Kerr T, Small W. Negotiating place and gendered violence in Canada’s largest open drug scene. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(3):608–15.

Kerr T, Mitra S, Kennedy MC, McNeil R. Supervised injection facilities in Canada: past, present, and future. Harm Reduct J. 2017;14:28.

Schäeffer D, Stöever H, Weichert L. Drug consumption rooms in Europe: models, best practices and challenges. Amsterdam: European Harm Reduction Network; 2014.

• McNeil R, Kerr T, Lampkin H, Small W. “We need somewhere to smoke crack”: an ethnographic study of an unsanctioned safer smoking room in Vancouver, Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(7):645–52. This paper describes the impacts of a peer-run unsanctioned safer inhalation room in reducing potential for health-related harms among people who inhale drugs.

Jozaghi E, Lampkin H, Andresen M. Peer-engagement and its role in reducing the risky behavior among crack and methamphetamine smokers of the Downtown Eastside community of Vancouver, Canada. Harm Reduct J. 2016;13(1):19.

Ti L, Buxton J, Harrison S, Dobrer S, Montaner J, Wood E, et al. Willingness to access an in-hospital supervised injection facility among hospitalized people who use illicit drugs. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(5):301–6.

BCC News. France's first drug room for addicts to inject opens in Paris [Internet]. 2016 October 11 [cited August 14 2017]. Available from: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-37617360

McNeil R, Kerr T, Pauly B, Wood E, Small W. Advancing patient-centered care for structurally vulnerable drug-using populations: a qualitative study of the perspectives of people who use drugs regarding the potential integration of harm reduction interventions into hospitals. Addiction. 2016;11(4):685–94.

Golden RE, Collins CB, Cunningham SD, Newman EN, Card JJ. Overview of structural interventions to decrease injection drug-use risk. In: Best evidence structural interventions for HIV prevention. New York, NY: Springer; 2013:41-121.

Shannon K, Rusch M, Shoveller J, Alexson D, Gibson K, Tyndall MW. Mapping violence and policing as an environmental–structural barrier to health service and syringe availability among substance-using women in street-level sex work. Int J Drug Policy. 2008;19(2):140–7.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Tricia Collingham and Deborah Graham for their research and administrative assistance. Mary Clare Kennedy is supported by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Doctoral Fellowship and a Mitacs Accelerate Award from Mitacs Canada. Mohammad Karamouzian is supported by a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship. Thomas Kerr is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Foundation Grant (20R74326).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Humans and Animal Rights

All reported studies/experiments with human or animal subjects performed by the authors have been previously published and complied with all applicable ethical standards (including the Helsinki declaration and its amendments, institutional/national research committee standards and international/national/institutional guidelines).

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on The Science of Prevention

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kennedy, M.C., Karamouzian, M. & Kerr, T. Public Health and Public Order Outcomes Associated with Supervised Drug Consumption Facilities: a Systematic Review. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 14, 161–183 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-017-0363-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-017-0363-y