Abstract

The customary mode of flat rate-property taxation used in the United States and many other Anglospheric countries encourages the consumption of ever greater volumes of energy and materials by relatively affluent households and exacerbates social inequalities. Transition from an invariable tax rate on residential real estate to a graduated schedule could enhance local sustainability by ameliorating the trend toward larger houses and associated increases in resource appropriation. This form of progressive property taxation was most notably implemented in New Zealand during the latter years of the nineteenth century, and has periodically attracted attention as a way to discourage the amassing of large landholdings in rural areas and to maintain housing affordability in cities. This paper considers the design and implementation challenges of a graduated property tax which, by dampening demand for outsized dwellings, could be a useful part of a comprehensive package of climate-change policies for local governments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sustainability researchers and policy makers have long recognized that fiscal policies can be effective in decreasing energy and material utilization and regularly endorse carbon and consumption taxes to modulate resource flows (Weber and Matthews 2008; De Camillis and Goralczyk 2013). This has especially been the case in the field of sustainable consumption which has developed over the past 2 decades to encourage absolute reductions both at the level of individual households and at the scale of the macroeconomy (Cohen et al. 2013; Reisch and Thøgersen 2015). Absent from consideration though has been the role that contemporary systems of local public finance have on home size, residential density, and overall settlement patterns. Of particular relevance is how the property tax is used by municipal governments to generate revenue to pay for education, police and fire protection, social services, physical infrastructure, and other essential activities. This paper seeks to identify opportunities for reforming the levy on real estate to encourage more sustainable consumption.

Though the property tax has not, to date, been widely viewed as a sustainability tool, this fiscal measure holds some very interesting potential.Footnote 1 Calculation of the underlying assessments is first and foremost a relatively straightforward process, and there is in most countries that rely on this means of raising public revenue extensive institutional capacity to perform the associated administrative tasks (Hale 1985; Slack and Bird 2014).Footnote 2 In addition, because of the non-portability of the taxable asset—real estate cannot be moved to an offshore account or, otherwise, hidden from view—it is extremely difficult for property owners to systematically evade payment. This effectiveness is further reinforced by the fact that local governments normally have broad legal authority to impose liens that prohibit the transfer of tax-delinquent property or to exercise seizure in the event of outstanding liabilities. As a general rule, levies on real estate are imposed on both residential and commercial uses, though, for purposes of simplicity, the focus here is exclusively on the former. While the United States provides the illustrative context for most of the following discussion, much of the ensuing analysis should be broadly adaptable to the unique policy frameworks of other (post-)industrial countries (see Pippin et al. 2010).Footnote 3

The implementation of policy measures to discourage residential upsizing is from a sustainability perspective important because housing accounts for approximately half of the greenhouse-gas emissions generated by consumption activity in high-consuming countries (Tukker et al. 2010). According to the United Nations Environment Program (2010), at the global scale, housing accounts for 44% of total energy use (see also Sanberg 2018). In addition, the carbon footprints of households typically increase as income rises because home size (as measured by residential square footage) is closely correlated with affluence (Giro and de Haan 2010; Isaksen and Narbel 2017; Sommer and Kratena 2017).Footnote 4 Moreover, larger dwellings require more expansive resource consumption in terms of both embodied energy associated with building materials and ongoing occupancy and tend to co-create low-density, automobile-reliant lifestyles (Wilson and Boehland 2005; Clune 2012; Stephan and Crawford 2016).Footnote 5

This vexing situation is further impelled by the economics of home construction, the bubbles that are recurrent in real-estate markets, the cultural norms of status signaling, and the importance of homebuilding for national economies (Megbolugbe and Linnemann 1993; Davidson 2009; Goldstein et al. 2015; Shiller 2017). Moreover, because of a need to continuously increase revenues to balance budgets, city planners and other local officials have in recent decades been complicit in encouraging construction of higher value properties, since they are more remunerative with respect to the property-tax revenue that they generate. This pattern has been particularly evident in relatively prosperous communities which have historically used property taxation (in conjunction with minimum building and lot sizes and other elements of zoning ordinances) to foster and perpetuate social exclusion (Zech 1980; Spinney and Kanaroglou 2012).

There is thus strong rationale for restructuring the property tax to serve as a tool for enhancing rather than undermining sustainability and to put housing policy at the center of discussions about sustainable consumption (Heyer and Holden 2001; Gram-Hanssen 2015; Sanberg 2018). To achieve this aim, the paper investigates the notion of a graduated property tax (GPT) based on a schedule that progressively shifts the local tax burden from lower valued to higher valued properties. The next section explains the operational details of how a GPT works. The third section discusses the origins of this idea and the fourth section highlights several recent efforts to deploy it. The fifth section describes the role of a GPT in facilitating more sustainable consumption and the final section considers several political issues pertaining to its ultimate implementation.

The basics of a graduated property tax

In the United States, and to varying degrees in other Anglospheric countries, the conventional approach for collecting property taxes is generally acknowledged for its regressive qualities (Musgrave 1974; Piketty and Saez 2007).Footnote 6 This means that, within a particular community, the incidence of the levy tends to fall more heavily on less rather than more valuable properties and this inequality has adverse social implications.Footnote 7 These untoward effects arise, because local governments generally impose a uniform tax rate on all properties of the same functional class regardless of physical size or market price (this is known as the mill or millage rate, and it is typically calculated per $1000 of assessed valuation). In other words, houses with widely divergent values—say $250,000 and $1 million—normally pay property tax at the same percentage of assessed valuation (though the latter, of course, has an annual bill that is four times greater, since the market price of the dwelling is fourfold higher). The owners of lower valued houses thus shoulder an inequitable proportion of the overall tax burden, while relatively affluent individuals are implicitly encouraged to favor more sizeable residences.Footnote 8

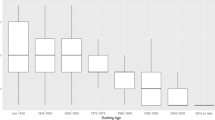

One way to address this problem is through implementation of a graduated property tax (GPT) scaled to the value of the underlying real estate (land and buildings). Such a measure would reduce the regressiveness of customary flat rate-property taxation (potentially even turning it into a progressive tax) while simultaneously discouraging the construction and occupancy of increasingly larger residences.Footnote 9 In terms of its practical design, the owners of comparatively modest homes would be assigned a relatively low tax rate and the percentage would steadily rise in proportion to the assessed value of the dwelling. The schedule could be constructed on the basis of a stepwise, linear, or curvilinear formula (Fig. 1).Footnote 10 For example, a house appraised at, say, $250,000 would have an annual mill rate of 2% (or $5000 yearly tax payment), a residence valued at $500,000 would be taxed at a 3% rate (or $15,000 yearly tax payment), and a home with an assessed value of $1 million would pay a yearly rate of 4% (or $40,000 yearly tax payment) (Table 1).

A GPT would shift the incidence of the tax toward wealthier households and, if formulated with a sufficiently steep gradient, create a deterrent to residential upsizing and the increased resource consumption embodied in this trend.Footnote 11 To enhance overall effectiveness of the measure, the revised levy on property could be implemented as part of a more comprehensive policy package that included (1) eliminating the mortgage-interest deduction (by capping eligibility or calibrating the subsidy in accordance with a sliding scale) that homeowners in some countries (including the United States) are able to claim against their income taxes and (2) increasing tax rates on capital gains derived from home sales.Footnote 12

Historical background

In western political economic thought, the notion of a GPT (or alternatively referred to as a progressive property tax, a graduated land tax, or graduated real-estate tax) emerged during the first half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 13 Various pamphlets outlining the case supporting such a levy circulated during the 1820s and John Stewart Mill devoted considerable attention to the concept in his 1848 treatise, Principles of Political Economy.Footnote 14 At one point in the book, he observed,

Setting out, then, from the maxim that equal sacrifices ought to be demanded from all, we have next to inquire whether this is in fact done by making each contribute the same percentage on his pecuniary means. Many persons maintain the negative, saying that a tenth part taken from a small income is a heavier burthen than the same fraction deducted from one much larger: and on this is grounded the very popular scheme of what is called a graduated property tax.

Mill, though was not—at least at this point in his career—an advocate of the idea and in fact, his commentary on the subject presaged arguments that have remarkable resonance today.

I am as desirous as any one that means should be taken to diminish those inequalities, but not so as to relieve the prodigal at the expense of the prudent. To tax the larger incomes at a higher percentage than the smaller is to lay a tax on industry and economy; to impose a penalty on people for having worked harder and saved more than their neighbors. It is not the fortunes which are earned, but those which are unearned, that it is for the public good to place under limitation. A just and wise legislation would abstain from holding out motives for dissipating rather than saving the earnings of honest exertion.

Despite Mill’s reservations, several proposals to implement versions of a GPT were debated at the time in the British Parliament and the idea subsequently received consideration in a number of other countries. Perhaps, most noteworthy is the interest that it attracted in New Zealand which confronted numerous political challenges regarding land tenure after achieving self-governance in 1852, particularly with respect to decisions regarding the sale or lease of crown lands. The essence of the problem was how to prevent wealthy owners from accumulating large estates and thus denying smallholders sufficient opportunity to gain a tenured foothold or maintain an agricultural living.

The tendency toward the so-called “land monopolies” in New Zealand was exacerbated by the colony’s temperate climate and ample availability of water and the long-growing season reduced or eliminated costs common at the time in, say, Canada or the United States. Writing at the time, economist William Downie Stewart (1909a) noted that “the only limit to the extent of country that the farmer can stock is the limit of his purse.” The legislature and provincial government experimented with numerous measures over the years to address the situation with many of them regularly modified or discarded and replaced. By one count, the colony’s Land Act of 1892 repealed 52 separate acts and ordinances, and was itself amended 68 times before the end of the first decade of the twentieth century (Stewart 1909a, b; McDonald 1952; Greasley and Oxley 2009; see also Pawson and Brooking 2013)

To encourage the break-up of large estates and to promote “closer settlement,” the Land for Settlement Act of 1894 introduced a GPT based on landholding size.Footnote 15 During the early iterations of the new tax property, owners were able to circumvent the graduated payments by employing a variety of subterfuges (for example by spreading ownership among family members but continuing to work the estate as a single parcel). A series of subsequent amendments introduced as part of the Land and Income Assessment Act of 1907 tightened the prior arrangements and

[A] heavy increase was made wherever the unimproved value exceeded ₤40,000. In addition to the existing graduated tax an additional 8 shillings for every ₤100 over ₤40,000 was added which increased progressively thousand by thousand by 1/5 of a shilling up to 2%, until an unimproved value of ₤200,000 was reached. Above this no further increase occurs. However, this is not all. After the lapse of 1 year, the graduated tax is increased by 25%! At the same time, the absentee tax was increased by 50%. In addition, the definition of an absentee made more strict to catch those who were in the habit of paying flying visits to the Colony to evade the tax.Footnote 16

These measures seem to have achieved their strategic intent, particularly if the vigorousness of the backlash from large landowners is used as a gauge. One vociferous critic intoned that the GPT was “doing its best to turn a colony of self-reliant, hardworking people into a race of slouching cadgers who in another generation will want to give up work altogether for the congenial pastime of filching the property of those who have anything left to be stolen, if the latter have not already cut the country” (quoted in Stewart 1909b, pp. 151).

Fifty years later, the idea of a GPT was taken up in the American state of North Dakota which was experiencing similar problems of land consolidation in the years following World War II due to agricultural mechanization and other economic and demographic changes. The issue was put to a public vote in 1950 as part of a statewide referendum. The ballot statement called for “providing an amendment to the constitution of the State of North Dakota, relating to taxation and authorizing the people or the Legislature to subject property to a Progressive Graduated Land Tax increasing according to area and value or both”. The proposal was roundly defeated by a tally of 110,567–38,561 votes.Footnote 17

Contemporary examples of graduated property taxation

In recent years, several jurisdictions around the world have sought to enact a GPT. While the record of achieving actual implementation is mixed, notable efforts have been pursued in Singapore, the American states of Minnesota and Massachusetts, and a small handful of other places. The following section provides brief reviews of these cases.

First, the city–state of Singapore has had, over the past decade, one of the most expensive housing markets in Asia.Footnote 18 After deploying without significant success several modest anti-speculation strategies to rein in ever-escalating prices, especially for luxury and investment properties, the government imposed, in February 2013, a GPT that applied to the topmost 1% of owner-occupied residences. Effective as of January 2015, the tax added 12–20% to the overall purchase price of approximately 12,000 specifically targeted high-end homes (a separate but related measure was applied to properties acquired by foreign investors) (Tomlinson 2013).

In making the announcement about the new levy, the finance minister at the time, Tharman Shanmugaratnam, remarked that “[t]he property tax is a wealth tax and is applied irrespective of whether lived in, vacant or rented out. Those who live in the most expensive homes should pay more property tax than others” (quoted in Yahya 2013). Yee Jenn Jong, a non-elected member of the Singaporean parliament representing the Workers’ Party echoed these sentiments, observing that “[t]here’s been a lot of people that have made a lot of money through property and the government is using that as a way to get additional revenue to offset certain goodies they’re giving to those in the lower income” (quoted in Thakur and Chen 2013).

Second, motivated by a commitment to reduce the regressiveness of the property tax, advocates in the American state of Minnesota made significant progress in 2008 toward implementation of a de facto GPT. The initiative called for establishing a “homeowners’ property-tax refund” on a means-tested basis. More specifically, the measure entailed a back-fitting process, whereby households with an annual income of less than $200,000 would receive from the state a rebate for property taxes paid in excess of 2% of household income. This provision was coupled with a several other adjustments, including elimination of an existing property tax-refund schedule and the state income-tax deduction for property taxes. The repeal of these other programs was intended to enable the state to absorb the cost of the new refunds. The complicated workings of the bill were necessitated by the fact that the governor at that time had vouched to defeat attempts to impose any new taxes. In its first year of operation, this novel program would have effectively lowered annual property taxes for average low-income, moderate-income, and high-income homeowners by, respectively, approximately $60, $220, and $180. Yearly property taxes for very high-income homeowners would have increased on average by $300. The resulting bill passed in the state’s House of Representatives by a vote of 80–52 but subsequently died due to inaction on the part of the Senate (Van Wychen 2008).Footnote 19

Third, the western Massachusetts town of Great Barrington, a resort community in the Berkshire Mountains with a population of approximately 7100 people (and upwards of seventy restaurants), considered a proposal to implement a GPT in 2015.Footnote 20 The initiative was led by the Chair of the town’s Finance Committee who had, for some time, been seeking a way to reduce the regressiveness of the local property tax and to enhance housing affordability. The proposition was debated at an overflowing public meeting held at the local firehouse and a total of 17 speakers strenuously voiced opposition to the idea. At the end of the 2½-hour gathering, members of the assembled group were asked to express their views by raising their hands; only three people did so. The Finance Committee then voted 3–2 to retain the prevailing flat rate-property tax (Bellow 2015).Footnote 21

Finally, it merits briefly mentioning three other instances to implement a GPT that have been derailed by political shifts, defeated by opponents, or impeded by the absence of a window of political opportunity. In 2009, a socialist government in Hungary led by Prime Minister Gordon Bajnai put into effect a GPT as part of a comprehensive overhaul of the country’s fiscal policies. However, the initiative subsequently became embroiled in debates over its constitutionality and was then reversed by the populist government that came to power the following year (Farkas 2009).Footnote 22

In another case, a coalition of political parties in Cyprus pressed in 2016 for elimination of the prevailing flat rate-property tax and establishment of a GPT in its place. The proposition was supported by the Progressive Party of Working People (AKEL) and the Democratic Party (DIKO) as a way to reform the country’s Immovable Property Tax (IPT). Advocates called for staggering the GPT, exempting low-value properties, and imposing a steeper rate on higher value real estate. Upon defeat of the measure, AKEL spokesperson Giorgos Loucaides remarked that “The government has left the less-privileged to pick up the tab in a bid to serve big private interests” (quoted in Theodorides 2016).

Finally, as in the United States, Canadian cities are heavily reliant on property taxes to fund local budgets with some municipal governments deriving as much as 60% of their revenue from this source (in part because they do not have authority to impose an income tax). Interestingly, the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) has, in recent years, taken up the cause of mobilizing a campaign to encourage adoption of a GPT (Miller 2014). It is still early in the overall process, but it warrants keeping a close eye on developments. There are several parts of the country where, under appropriate circumstances, support for progressive property taxation could take root. Quebec has a deep tradition of social democratic policy making and is arguably the province in Canada that has traditionally focused most actively on addressing inequality. Vancouver is regarded internationally as one of the “greenest” cities and there is potential that, with creative leadership, a GPT could mobilize considerable support. Finally, Saskatchewan is the home of long-serving socialist premier Tommy Douglas and has a storied history of progressive politics.Footnote 23 While the province has in more recent years drifted a fair distance away from these commitments, many of the institutions forged during prior times persist and could conceivably be reactivated to champion a GPT.Footnote 24

Graduated property taxation as a sustainable consumption strategy

Recent experience in Singapore, in combination with the upward spiral in the cost of housing in cities like London, New York, and San Francisco, has prompted a growing number of economists and other analysts to endorse a GPT (and GPT-related concepts) as a way to control rampant escalation of local property values. For example, Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz has pointed out that progressive taxation of real estate could contain soaring housing prices and help to reign in the social inequality perpetuated under such conditions. He has recommended imposing a stiff property tax on high-priced residences and using a portion of the revenue to “subsidize lower income people to live in the city” (quoted in Tencer 2015; see also Ball 2015).

While a GPT has much to commend as a stopgap measure to maintain housing affordability, municipal governments are increasingly recognized as being at the forefront of adapting to global environmental change and many of them have the authority to unilaterally implement creative policy ideas (Barber 2013; Acuto 2013; Graute 2016; Capps 2017).

It is probable that this issue will become more salient as the signatories of the Paris Climate Accords scrutinize their targets and actively begin to grapple with the obstacles of meeting them (Hsu et al. 2017; Alfredsson et al. 2018). During the course of this process, it is likely that the role of local governments in restructuring significant parts of the built environment will become a key part of climate-action plans (Boswell et al. 2011; Chapple 2016; Barber 2017). It is, after all, the physical context of everyday life—in particular the way that urban design and planning shapes housing and mobility practices—that, in aggregate, is responsible for determining national emission profiles (Bulkeley 2006; Niemeier et al. 2015; C40 Cities 2018).

Successful implementation of a GPT would, in the first instance, require political agreement on a commonly decided set of benchmarks regarding appropriate and equitable per capita resource utilization.Footnote 25 It would also oblige local governments to overcome deeply seated prerogatives that, in general, favor the construction of relatively larger and higher tax-paying homes over smaller and less remunerative dwellings. Municipal authorities would also need to transcend a tendency to regard themselves as locked-in victims of a problematic status quo and reaffirm their responsibility as champions of both environmental and social sustainability (Barber 2013). This assertion would require going beyond familiar platitudes that encourage energy and materials efficiency, renewable sources, and technological innovation, and, instead, facilitate identification of community standards with respect to sufficiency and economic security (see, for example, Princen 2005; Standing 2011).Footnote 26

We can refer to this conventional approach, where municipal governments establish an upward-trending gradient based on assessed value for determining the rate at which homeowners are required to pay property tax, as ordinary GPT. If calibrated correctly, this variant could have, ceteris paribus, an expedient derivative effect of generating surplus revenue that could be used to invest in sustainability-enhancing infrastructure and social programs.Footnote 27

A second variant for realizing a GPT calls not on raising the property-tax rate on relatively higher value homes but instead on reducing it on lower value residences. While this is likely to be more politically practicable, it would not have the beneficial feature of producing supplementary revenue for environmental and social investments. This mode of progressive property taxation is termed abatement-based GPT, and it is modeled on the enterprise programs that various countries and subnational units of government have created in recent decades to enable local jurisdictions to downwardly adjust property taxes (or eliminate them altogether) within a stipulated geographic area for a predetermined period of time.Footnote 28

Third, by borrowing on experience from Minnesota and the notion of homestead property tax-relief programs in the United States more generally, a third variant is rebate-based GPT. This option would not actually be a tax, but rather entail a post-tax adjustment that provided owners of lower value homes with an annual refund in proportion to the assessed value of their property (or pegged to household income). The ultimate effect of this measure would be to shift the property tax toward more affluent residents who would be eligible for a smaller rebate or perhaps none at all.

Finally, a more traditional—and in many respects straightforward—approach for realizing many of the objectives of a GPT without undue administrative or logistical complications would be to impose a supplementary post-tax levy on all real estates above a particular value threshold. This alternative would, for all intents and purposes, be a luxury tax that could be applied either on a fixed or percentage-determined basis. The option would have the added advantage of generating surplus revenue that could be directed to sustainability investments in the community.

We can conceptually organize these variants for reforming the customary property tax using a two-dimensional typology that contrasts the timing of the property-tax adjustment (pre-tax vs. post-tax) and the relative value of the property primarily targeted by the policy change (higher value vs. lower value) (see Fig. 2). Ordinary GPT involving a pre-tax adjustment of higher value homes is situated in Quadrant 1. Abatement-based GPT is depicted in Quadrant 2 and rebate-based GPT is in Quadrant 3. Finally, the luxury tax alternative is located in Quadrant 4.

As a general characterization, the two alternatives in the upper half of the figure (ordinary GPT and luxury tax) are preferable as sustainability strategies because of their capacity to simultaneously suppress tendencies toward residential upsizing and to generate a source of funding for public improvements that reduce energy and material utilization. These desirable features are offset by the fact that both variants are likely to face considerable resistance from politically formidable constituencies. By contrast, the two alternatives in the lower half of Fig. 2 (abatement-based and rebate-based GPT) hold the prospect of being more politically feasible. This upside is though counterpoised by two disadvantages: they are likely to be costly to implement and their budgetary implications will need to be compensated by other sources of revenue. Furthermore, post-tax modifications are less apt to discourage construction and occupancy of outsized properties by more affluent households.

Conclusion

During an era when neoliberal (and post-neoliberal) mindsets and political imperatives remain pervasive, many observers are inclined to regard a GPT to encourage more sustainable consumption as exceeding the customary powers of local governments.Footnote 29 A prevalent perspective is that it is not the role of mayors and city councils to determine housing choices or to influence the workings of the “free market.” This is clearly a false understanding. Local governments, through the imposition of the property tax (as well as other legally vested responsibilities like the application of land-use controls), have long been profoundly implicated in the shaping of both contemporary housing decisions and consumption practices more generally (Jackson 1985; Cohen 2003). The real issue is that the overwhelming emphasis of municipal authorities, especially in affluent suburban communities, has been to encourage residential upsizing and increasing volumes of energy and materials utilization.Footnote 30 Accordingly, a critical requirement is the need for local governments to change their priorities and the way in which already existing powers are exercised. Overcoming this obstacle will be far more important than innovating a new set of policy tools. In other words, what is required is a cultural and political shift that redefines the target objective—a turn that diminishes unreflective pursuit of economic growth and expands emphasis on creating the conditions that enable all people to live well within biophysical limits. While it would be misleading to underestimate the scale of the challenges, it may be easier for municipal governments to set their sights on this goal than it is for their national counterparts because the conditions of everyday life are more tangible and consequential at the local level (Ortegon-Sahchez and Tyler 2016; de Leeuw and Simos 2017).

Although underlying pressure for transitions of this order of magnitude accumulates gradually over a long period of time, history suggests that ultimate social change often comes about only during the aftermath of war or other major exigency (Geppert 2003; Helperin 2004; Cohen 2011). We now appear to be reaching a stage where this eventuality is now upon us and it may very well be the forcing effects of climate change that will be the catalyst for transformation. The point at which a GPT moves from being a quixotic idea to a normalized fiscal tool could be approaching, and it is, moreover, not inconceivable that we will see before too long relatively affluent homeowners coming to regard progressive property taxation more as an opportunity than a threat. Let us trace out a plausible scenario based on the well-established notion of a special tax-assessment district.Footnote 31

At least in wealthy nations, littoral property tends to be more highly valued than corresponding inland alternatives (Jin et al. 2015; McNamara et al. 2015). As a result, it can be posited that relatively affluent homeowners will be first to experience the adverse effects of sea-level rise, storm surges, and other related phenomenon (indeed, this is already the case in a growing number of coastal zones). A first avenue of recourse will be for the occupants of susceptible beachfront homes to seek to enlist local (or higher levels of) government and to use the existing taxing authority to spread the onerous costs of armoring investments. In some locales, shear power politics will ultimately, but unfairly, carry the day and both extremely vulnerable and less vulnerable homeowners will share the expense.Footnote 32 In other jurisdictions with fortunate capacity for more democratic decision-making, such cost-shifting efforts will fail. In these cases, the holders of shoreline property, if they are to protect themselves from repeated inundation and other damage, will need to muster themselves to absorb a larger proportional burden of the outlay (Urbina 2016; Lieber 2016). Such circumstances may prompt a need to establish “coastal compacts” which would be, for all intents and purposes, special tax-assessment districts charged with responsibility for constructing protective infrastructure. The differentiation of properties within a community according to whether they are located inside or outside of the hazard-demarcated area would then provide the rationale to create a gradient for determining property-tax rates on the basis of relative value.Footnote 33 Over time, this arrangement could evolve into a more fully fledged ordinary GPT.Footnote 34

It is furthermore worthwhile to revisit Fig. 2 to identify several issues that are prone to influence the specific design features of a GPT. Earlier discussion described the distinction between pre-tax versus post-tax variants as well as the differences between measures that impinge on the owners of relatively high-value properties versus those that seek to assist holders of comparatively low-value real estate. In addition, pre-tax policy interventions (left side of the figure) are likely to become more successfully institutionalized and difficult to reverse over time because they will become embedded and inviolate features of the budget-making process. By contrast, post-tax variants (right side of the figure) are apt to be regarded as more transient features of the policy landscape and hence amenable to revision or outright elimination when fiscal conditions change or political winds blow in a different direction.

Second, there are distinct advantages to designing a GPT with more—rather than fewer—steps in the schedule. Indeed, as depicted in Fig. 1, the optimal solution may be a gradient that has a curvilinear shape without any discrete break points. This feature would diffuse opportunities for cohort effects where the structure of the scheme provides an organizational logic for property owners to mobilize into discrete groups to voice opposition. In addition, a continuous schedule eliminates the possibility that real-estate appraisers will have a tacit incentive to undervalue properties and to fix actual assessments just below rather than above critical thresholds. The steepness of the gradient will, of course, need to be resolved through political negotiation.

Third, in the absence of geographic isolation or exceptional attributes, it would likely prove difficult for a single community to enact a GPT on its own and a more effective approach would be to proceed on the basis of a regional strategy. Under ordinary conditions, affluent households obliged to pay stepped up property taxes could be inclined to exercise a flight option and choose to live instead in a neighboring jurisdiction that retained a flat-rate levy. This is not a unique problem. Whenever proximate opportunities exist to avoid differential policy treatment, narrowly construed self-interest will lead to a certain amount of defection. The challenge would then be for local government to manage this situation while recognizing that it is not trivial for the existing residents to move house in the short-to-medium term.Footnote 35 By contrast, recruitment of new homeowners could conceivably be more difficult if the community is part of a region with several similar residential options and a pattern of inter-jurisdictional competition over property-tax rates (Brueckner and Saavedra 2001; Grassmueck 2011).

Fourth, communications specialists and others have long highlighted the challenges associated with the term “sustainable consumption” and the matter of a GPT puts these problems in bold relief (see Kilbourne 2004; Heiskanen et al. 2014). As efforts to date to mobilize public support for progressive property taxation already make clear, a more strategic posture would be to emphasize notions of fairness and affordability rather than more contested objectives such as resource sufficiency and global solidarity. In addition, in communities experiencing residential upsizing popular appeal to preserve “neighborhood character” in the face of exogenously imposed disruption can often be an effective trigger.Footnote 36

Fifth, the New Zealand and Singapore cases represent two very different applications of a GPT—the former to encourage the break-up of large agricultural landholdings and the latter to reduce incentives for speculation in a densely urbanized city–state. The relative ease with which a stepwise levy on rural property can be evaded by subdividing acreage among various family members may help to explain why this technique never came to be widely applied in rural contexts.Footnote 37 Remedies for this problem though exist. One approach would be to set the GPT according to productivity (income per acre) rather than parcel size. The assessment then becomes a hybrid tax that would require the integration of property and income records. By contrast, a GPT could be more readily applied in an urban setting where the aim is instead to suppress demand for residential upsizing and to reduce resource consumption. At present, however, we lack adequate experience with how a GPT would work under different circumstances to make meaningful generalizations.

Finally, a sustainability transition involving a GPT would need to be pursued in conjunction with reform of other aspects of public finance that contribute to outsized utilization of energy and materials and exacerbate social inequalities. This is especially the case in countries where the income tax has, in recent decades, lost much of its progressive intent. Moreover, this measure may ultimately be easier to implement in cities and regions that have a robust labor market and a highly constrained housing supply, so that homeowners (and prospective homeowners) face a narrower menu of options. The challenge calls for a large-scale project on fiscal reform for a sustainable future.

Notes

Despite these features, Hale (1985) ruefully observes that “for most of this century, [the property tax] has been denounced as an unjustifiable relic of the Middle Ages, which has unaccountably survived into modern times.”

At the same time, it is important to observe that there is tremendous variability (both within and between countries) in property-tax rates, assessment procedures, appraisal techniques, appeal opportunities, and other administrative features. In addition, there is a little consistency in the degree to which jurisdictions rely on the property tax relative to other sources of public revenue. In the United States, according to a recent study by the Lincoln Institute for Land Policy, the city of Bridgeport (Connecticut) has the highest property-tax rate (3.88%). By comparison, the cities with the lowest tax rates are Honolulu (Hawaii), Denver (Colorado), and Cheyanne (Wyoming) which are, respectively, 0.30, 0.65, and 0.66% (Agarwal 2016). Among countries that are members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the UK relies most heavily on the property tax, accounting for 12.5% of total public revenue followed by South Korea (12.4%), Canada (11.8%), and the United States (10.5%). Nations least reliant on the property tax are Austria (1.2%), Germany (2.8%), Norway (2.8%), and Finland (3.2%) (see Romei 2017).

Refer to Harlan et al. (2009) for similar results pertaining to household-water consumption.

The term “housing” is meant to connote the construction and occupancy of the physical structure as well as the embodied energy in the building materials, utilities, furnishings, appliances, and other equipment. While efficiency improvements can reduce to some degree the effects of increasing interior space on greenhouse-gas emissions, there is a high correlation between home size and environmental impact. See also Badger (2011) and Moore et al. (2013).

Unlike the situation pertaining to the federal income tax, the United States does not have a nationally unified and consistent system for imposing and collecting levies on real estate. Most states have enabling legislation that grants to local governments the authority to assess property taxes and each local jurisdiction typically has its own administrative mechanisms for this purpose. As noted above, while there is thus considerable variability in the specific policies of different locales, the following discussion is based on certain generic features that for the most part apply independently of the particularities of specific communities. According to the Tax Policy Center, state and local governments in the United States collected $442 billion from property taxes in 2013 and this amount represented 47% of own-source general revenue. In some states, the proportion is substantially higher and this is especially the case in the northeastern region of the country where property taxes in Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, and Rhode Island account for upwards of 75% of local own-source revenue. See http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/how-do-state-and-local-property-taxes-work.

For a review of the literature on the regressiveness of the property tax, refer to Sirmans et al. (2008). See also Ihlanfeldt and Jackson (1982) and Sunderman et al. (1990). New York City has an unusually and particularly regressive levy on real estate and is a compelling example of how political influence shapes policies regarding property taxation. For an overview of this situation, refer to The Economist (2015).

In the United States, there are additional incentives that promote residential upsizing especially on the part of wealthier households. The primary inducement stems from a provision in the federal tax code allowing for the (now limited) deductibility of property taxes and mortgage interest. Hanson et al. (2014) claim that “evidence shows that, rather than encouraging the purchase of homes by people who might otherwise rent, the mortgage-interest deduction instead encourages the purchase of larger homes by people who would otherwise own smaller ones.” A number of countries (including most recently the United States) have abolished or substantially reduced allowable limits for the tax deductibility of mortgage interest. Other notable cases are Finland which instituted a major overhaul of the entitlement in 1993 and the UK which did away with it in 2000. For more extensive discussion, refer to Bartlett (2013); Hanson (2013); Keightley (2014); Cohen (2017).

It merits remarking that, among some economists, there are unsettled questions about the relative progressiveness vs regressiveness of the property tax. A thoroughgoing accounting of these debates is provided in Fischel et al. (2011). I am grateful to an anonymous referee for alerting me to this issue and bringing this reference to my attention.

As depicted in Fig. 1, a GPT could also be calibrated on a linear or curvilinear schedule.

Similar outcomes could be derived by operationalizing a property-tax system based on “graduated assessment” (also termed “differential assessment”) instead of a graduated rate. In the United States, this procedure would be illegal as it would violate the due process provisions of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution. In actual practice, assessments are recalculated (generally as a percentage of market value) on a regular basis (10-year intervals are fairly common), but during intermediary periods characterized by geographically uneven conditions, there may be within particular neighborhoods considerable temporary deviation between assessed and market value.

In the United States, the first part of this prescription was to a large degree achieved by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2018 which caps through 2025 the interest deduction on federal taxes at $750,000 of mortgage debt. This legislation also limits the credit that a homeowner can claim for state and local taxes (including local property taxes) to $10,000.

As von Glahn (2011) notes, during the early years of the sixteenth century, a GPT system was fairly widespread in China, most notably in Nanjing, Beijing, and Hangzhou.

“Closer settlement” was a term used at the time in New Zealand to connote the need to more densely and equitably redistribute land. Refer to van Alphen Fyfe (2016).

Quoted in Stewart (1909b), pp. 149–150. The author also relates the following useful examples to illustrate how the GPT worked in practice.

Under the old system, an estate of the unimproved value of ₤1, 40,000 might be nominally subdivided among a family of 10 who would then pay graduated tax at 5/15 d. in the pound which would amount each year to ₤182: 5s. 10d. Under the new act the estate would be treated as a single estate and would be liable to 28 shillings per cent. This would yield a yearly contribution of ₤1960…On an estate worth ₤200,000 the graduated tax is ₤2: 10s per cent., and this, with ordinary land tax in addition, would amount to ₤5833: 16s. 8d. If the owner also lived out of New Zealand and came within the definition of an absentee, his total tax on such a property would equal ₤8750: 15s. (p 150).

Singapore has shared this distinction with Hong Kong with the two cities swapping the number one position over the past few years. After considering a GPT-type measure, the government of Hong Kong decided during the same timeframe to instead double the stamp duty on all residential and non-residential properties valued at HK$2 million (US$258,000) purchased by buyers without permanent residence status.

It merits noting that a number of American states have from time to time provided similar property-tax refunds on an across-the-board basis or targeted them to specific types of homeowners. Especially popular have been the so-called homestead property tax-relief (or “circuit breaker”) programs designed for elderly homeowners.

Despite its small size, Great Barrington is a notable community for several reasons. The town is the birthplace of the African-American scholar and activist W. E. B. Du Bois and the site of the first demonstration project of the Stanley transformer [developed by inventor William Stanley and the technology for subsequent alternating current (AC) electrical power systems]. It was also the backdrop for Arlo Guthrie’s popular folksong, Alice’s Restaurant, and is famous within new economics circles for implementing the BerkShares local currency. Smithsonian magazine in 2012 ranked Great Barrington #1 on its list of “The 20 Best Small Towns in America.”

The text of the proposal developed by Great Barrington’s Finance Committee is at http://theberkshireedge.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Revenue-options-08-14-15.pdf.

I am grateful to Edina Vadovics for clarifying my understanding of the details of the Hungarian case.

Douglas served as the seventh premier of Saskatchewan from 1944 until 1961 and is remembered today most notably for the role that he played in implementing the first single-payer universal healthcare system in North America.

I acknowledge here the insights of Anders Hayden about the Canadian political landscape but absolve him of any responsibility for the particular interpretation that is presented.

Additionally relevant is the notion of “consumption corridors” as outlined in Di Giulio and Fuchs (2014).

Another consideration is the potential of perverse rebound effects where a GPT successfully suppresses the demand of relatively affluent households for residential upsizing but subsequently results in the reallocation of available money (or borrowing capacity) to alternative forms of consumption other than housing (including the possible acquisition of a second home). For a useful discussion with respect to housing, refer to Næss (2016) while recognizing that rebound effects are a much more pervasive dilemma.

The establishment of enterprise zones is a common economic development strategy in many countries, and is typically implemented to encourage job creation and community revitalization. An example is the Neighborhood Enterprise Zone (NEZ) Program that has been operating in the American state of Michigan since 1992. An instructive fact sheet outlining the details of this initiative is at https://www.miplace.org/globalassets/media-documents/placemaking/community-development-guide/neighborhood-enterprise-zone-pa-147.pdf. The tax-incidence implications of enterprise zones are an area of active research in urban economics. See, for example, Bond et al. (2013) and Hodge and Komarek (2016).

There is, of course, no shortage of discussion suggesting that the era of neoliberalism is winding down and new political avenues are opening up, though as current circumstances make clear, some of these trajectories are extremely portentous. Equally confounding are claims that neoliberalism, at least in certain quarters, has effectively reasserted itself. For example, refer to Crouch (2011) and Springer (2015).

To be sure, some local governments have sought to promote residential energy efficiency and other forms of “greening,” but, as a general rule, the potency of these initiatives pales in comparison to the potential of fiscal and land-use policies to impel consumption.

In parts of the United States, it is common for proximate property owners to organize themselves into special property tax-assessment districts for various purposes with the political backing and administrative support of local government. For example, a merchants association can establish a so-called business-improvement district (BID) to collect legally mandated and dedicated property taxes to pay for additional services ranging from street cleaning to security. Similar mechanisms are frequently used throughout the country by property owners within a delineated area to finance wastewater-treatment facilities, road improvements, or other public infrastructure.

It is more accurate to note that under existing regressive modes of property taxation, the owners of lower value, non-beachfront homes would paradoxically be forced to pay a disproportionate share of the cost of these investments.

This proposition is not dissimilar to requiring the owners of property located in heightened flood-risk zones to pay a premium on homeowner insurance.

Such friction is normal and derives from the existence of positive transaction costs. Creative local governments can use this situation to their advantage by publicizing other saliently attractive features that compensate for the pecuniary effects of the GPT on some households.

For instance, in many communities in the United States, there is pronounced aversion to the process of “mansionization” (also known pejoratively as “McMansionization”), whereby smaller preexisting homes are demolished to make way for newer and larger replacements. For example, refer to Nasar et al. (2007) and Miller (2012). Dowling and Power (2011) offer a useful strategy for newly envisaging the relationship between the consumption of housing and social status.

The literature on the New Zealand GPT provides an extensive inventory of the artful techniques implemented by owners of large landholdings during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century to escape from paying property tax at the higher rate. See, in particular, Stewart (1909b).

References

Acuto M (2013) City leadership in global governance. Glob Gov 19(3):481–498

Agarwal S (2016) The best and worst cities for property taxes in 2016. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/shreyaagarwal/2016/06/15/the-best-and-worst-cities-for-property-taxes-in-2016/#719e39bbd78d. Accessed 15 June

Alfredsson E, Bengtsson M, Brown H, Isenhour C, Lorek S, Stevis D, Vergragt P (2018) Why achieving the Paris Agreement requires reduced overall consumption and production. Sustain Sci Pract Policy 14(1):1–5

Anonymous (1830) A letter to the earl of Wilton, on the commutation of existing taxes for a graduated property and income tax. George Smith, Liverpool

Badger E (2011) The missing link of climate change: single-family suburban homes. Citylab. https://www.citylab.com/equity/2011/12/missing-link-climate-change-single-family-suburban-homes/650. Accessed 7 Dec

Ball D (2015) Joseph Stiglitz on Canada’s housing inequality. The Tyee. https://thetyee.ca/News/2015/11/23/Joseph-Stiglitz-Housing-Inequality. Accessed 23 Nov

Barber B (2013) If mayors ruled the world: dysfunctional nations, rising cities. Yale University Press, New Haven

Barber B (2017) Cool cities: urban sovereignty and the fix for global warming. Yale University Press, New Haven

Barkawi A, Heller P (2013) Property taxes and sustainability. Council on Economic Policies, Zurich. https://www.cepweb.org/property-taxes-and-sustainability. Accessed 7 June 2018

Bartlett B (2013) The sacrosanct mortgage interest deduction. The New York Times. https://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/08/06/the-sacrosanct-mortgage-interest-deduction/. Accessed 6 Aug

Bellow H (2015) Graduated property tax concept grilled at public hearing; Finance Committee votes to retain flat rate. The Berkshire Edge. https://theberkshireedge.com/graduated-property-tax-concept-grilled-at-public-hearing-finance-committee-votes-to-retain-flat-rate. Accessed 22 Aug

Bond S, Bardiner B, Tyler P (2013) The impact of enterprise zone tax incentives on local property markets in England: who actually benefits? J Prop Res 30(1):67–85

Boswell M, Greve A, Seale T (2011) Local climate action planning. Island Press, Washington, DC

Brueckner J, Saavedra L (2001) Do local governments engage in strategic property-tax competition? Natl Tax J 54(2):203–229

Buckingham J (1831) Outlines of a new budget for raising eighty millions by means of a justly graduated property tax. Effingham Wilson, London

Bulkeley H (2006) A changing climate for spatial planning. Plan Theory Pract 7(2):203–214

Capps K (2017) Here’s a way to make homes 10% more affordable. Citylab. https://www.citylab.com/equity/2017/06/heres-a-way-to-make-homes-10-percent-more-affordable/528954. Accessed 2 June

Chapple K (2016) Integrating California’s climate change and fiscal goals: the known, the unknown, and the possible. Sacramento: University of California Center. http://uccs.ucdavis.edu/copy_of_UCCSBacon20160214FINALpaper.pdf

C40 Cities (2018) Consumption-based GHG emissions of C40 Cities. London: C40 Cities (https://www.c40.org/researches/consumption-based-emissions)

Clune S, Morrissey J, Moore T (2012) Size matters: house size and thermal efficiency as policy strategies to reduce net emissions of new developments. Energy Policy 48:657–667

Cohen L (2003) A consumers’ republic: the politics of mass consumption in postwar America. Vintage, New York

Cohen M (2011) Is the UK preparing for “war”? Military metaphors, personal carbon allowances, and consumption rationing in historical perspective. Clim Chang 104:109–222

Cohen M (2017) The future of consumer society: prospects for sustainability in the new economy. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Cohen M, Brown H, Vergragt P (eds) (2013) Innovations in sustainable consumption: new economics, socio-technical transitions, and social practices. Edward Elgar, Northampton

Coventry G (1833) Graduated scale for a property tax. Dean and Munday, London

Crouch C (2011) The Strange non-death of neo-liberalism. Polity, Malden

Davidson N (2009) Property and relative status. Mich Law Rev 107(5):757–817

De Camillis C, Goralczyk M (2013) Towards stronger measures for sustainable consumption and production policies: proposal for a new fiscal framework based on a life cycle approach. Int J Life Cycle Assess 18(1):263–272

de Leeuw E, Simos J (eds) (2017) Healthy cities: the theory, policy, and practice of value-based urban planning. Routledge, New York

Di Giulio A, Fuchs D (2014) Sustainable consumption corridors: concepts, objections, and responses. GAIA 23(S1):184–192

Dowling R, Power E (2011) Beyond McMansions and green homes: thinking household sustainability through materialities of homeyness. In: Gorman-Murray A, Lane R (eds) Material geographies and household sustainability. Routledge, New York, pp 75–88

Farkas Z (2009) Hungarian bubbles. Eurozine. http://www.eurozine.com/hungarian-bubbles. Accessed 18 June

Fischel W, W. Oates, J. Youngman (2011) Are local property taxes regressive, progressive, or what? Unpublished paper http://econweb.umd.edu/~davis/eventpapers/OatesLocalProperty.pdf

Fisher G (1996) The worst tax? A history of the property tax in America. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence

Garasky S, Haurin D (1997) Tiebout revised: redrawing jurisdictional boundaries. J Urb Econ 42(3):366–376

Geppert D (2003) The postwar challenge: cultural, social, and political change in western Europe, 1945–1958. Oxford University Press, New York

Giro B, de Haan P (2010) More or better? A model of changes in household greenhouse gas emissions due to higher income. J Ind Ecol 14(1):31–49

Goldstein A, N Fligstein, O Hastings. (2015) Keeping up with the Jonses: lifestyle competition and housing consumption in the era of the housing price bubble, 1999–2007. Berkeley, CA: University of California Berkeley, Institute for Research on Labor and Employment (http://irle.berkeley.edu/keeping-up-with-the-joneses-lifestyle-competition-and-housing-consumption-in-the-era-of-the-housing-price-bubble-1999-2007)

Gram-Hanssen K (2015) Housing in a sustainable consumption perspective. In: Reisch L, Thøgersen J (eds) Handbook of research on sustainable consumption. Edward Elgar, Northampton, pp 178–191

Grassmueck G (2011) What drives intra-county migration? The impact of local fiscal factors on Tiebout sorting. Rev Reg Stud 41(2–3):119–138

Graute U (2016) Local authorities acting globally for sustainable development. Reg Stud 50(11):1931–1942

Greasley D, Oxley L (2009) The pastoral boom, the rural land market, and long swings in New Zealand economic growth, 1873–1939. Econ Hist Rev 62(2):324–349

Hale D (1985) The evolution of the property tax: a study of the relation between public finance and political theory. J Politics 47(2):382–404

Hanson A (2013) Limiting the mortgage interest deduction by size of home: effects on the user cost and price of housing across metropolitan areas. J Hous Res 23(1):1–20

Hanson A, Brannon I, Hawley Z (2014) Rethinking tax benefits for home ownership. Natl Aff 32(Summer):40–54

Harlan S, Yabiku S, Larsen L, Brazel A (2009) Household water consumption in an arid city: affluence, affordance, and attitudes. Soc Nat Res 22(8):691–709

Heiskanen E, Mont O, Power K (2014) A map is not a territory: making research more helpful for sustainable consumption policy. J Consum Policy 37(1):27–44

Helperin S (2004) War and social change in modern Europe: the great transformation revisited. Cambridge University Press, New York

Heyer G, Holden E (2001) Housing as a basis for sustainable consumption. Int J Sustain Dev 4(1):48–58

Hodge T, Komarek T (2016) Capitalizing on neighborhood enterprise zones: are Detroit residents paying for the NEZ homestead exemption? Reg Sci Urb Econ 61:18–25

Hsu A, Weinfurter A, Xu K (2017) Aligning subnational climate actions for the new post-Paris climate regime. Clim Chang 142(3–4):419–432

Ihlanfeldt K, Jackson J (1982) Systematic error adjustment and interjurisdiction property tax capitalization. South Econ J 49:417–427

Isaksen E, Narbel P (2017) A carbon footprint proportional to expenditure: a case for Norway? Ecol Econ 131:152–165

Jackson K (1985) Crabgrass frontier: the suburbanization of the United States. Oxford University Press, New York

Jin D, Hoagland P, Au D, Qiu J (2015) Shoreline change, seawalls, and coastal property values. Ocean Coast Manag 114:185–193

Keightley M (2014) The mortgage interest and property tax deductions: analysis and options. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service (http://nationalaglawcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/assets/crs/R41596.pdf)

Kilbourne W (2004) Sustainable communication and the dominant social paradigm: can they be integrated? Mark Theory 4(3):187–208

Lieber R (2016) You’re buying a home. Have you considered climate change? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/02/your-money/youre-buying-a-home-have-you-considered-climate-change.html. Accessed 2 Dec

Martin I (2008) The permanent tax revolt: how the property tax transformed American politics. Stanford University Press, Palo Alto

McDonald J (1952) New Zealand land legislation. Historical Studies: Australia and New Zealand 5(19):195–211

McNamara D, Gopalakrishnan S, Smith M, Murray A (2015) Climate adaptation and policy-induced inflation of coastal property value. PLoS One 10(3):e0121278

Megbolugbe I, Linnemann P (1993) Home ownership. Urb Stud 30(4–5):659–682

Meyer A (2004) Briefing: contraction and convergence. Proc Inst Civil Eng Eng Sustain 157(4):189–192

Miller B (2012) Competing visions of the American single-family home: defining McMansions in the New York Times and Dallas Morning News, 2000–2009. J Urb Hist 38(6):1094–1113

Miller K (2014) Building better communities: A fair funding toolkit for Canada’s cities and towns. Ottawa: Canadian Union of Public Employees (https://cupe.ca/building-better-communities-fair-funding-toolkit-canadas-cities-and-towns)

Moore T, S Clune, J Morrissey (2013) The importance of house size in the pursuit of low carbon housing. In: N Gurran, B Randolph (eds) Proceedings of the State of Australian Cities, Sydney. p 1–10, 26–29 Nov

Musgrave R (1974) Is a property tax on housing regressive? Am Econ Rev 64(2):222–229

Næss P (2016) Urban planning: residential location and compensatory behaviour in three Scandinavian cities. In: Santarius T, Walnum H, Aall C (eds) Rethinking climate and energy policies: new perspectives on the rebound phenomenon. Springer, Berlin, pp 181–207

Nasar J, Evans-Cowley J, Mantero V (2007) McMansions: the extent and regulation of super-sized houses. J Urb Des 12(3):339–358

Niemeier D, Grattet R, Beamish T (2015) “Blueprinting” and climate change: regional governance and civic participation in land use and transportation. Environ Plan C (Gov Policy) 33(6):1600–1617

Opschoor H (2010) Sustainable development and a dwindling carbon space. Environ Resour Econ 45(1):3–23

Ortegon-Sahchez A, Tyler N (2016) Constructing a vision for an “ideal” future city: a conceptual model for transformative urban planning. Transp Res Procedia 13:6–17

Pan X, Teng F, Wang G (2014) A comparison of carbon allocation schemes: on the equity-efficiency tradeoff. Energy 74:222–229

Pawson E, Brooking T (2013) Making a new land: environmental histories of New Zealand. Otago University Press, Otago

Piketty T, Saez E (2007) How progressive is the US federal tax system? A historical and international perspective. J Econ Perspect 21(1):3–24

Pippin S, Tosun M, Carslaw C, Mason R (2010) Property tax and other wealth taxes internationally: evidence from OECD countries. Adv Tax 19:145–169

Princen T (2005) The logic of sufficiency. MIT Press, Cambridge

Reiner D (2005) Secession in the Garden State: the secession movement in Essex County, New Jersey and the law of deannexation. Rutgers Law Rev 57:1417–1446

Reisch L, Thøgersen J (eds) (2015) Handbook of research on sustainable consumption. Edward Elgar, Northampton MA,

Romei V (2017) UK’s property tax revenues are highest in OECD. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/1aa9eb98-ff3e-11e6-8d8e-a5e3738f9ae4. Accessed 2 Mar

Sabine B (1966) A history of income tax. Allen and Unwin, London

Sanberg M (2018) Downsizing of housing: negotiating sufficiency and spatial norms. J Macromarketing 38(2):154–167

Shiller R (2017) The transformation of the “American Dream.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/04/upshot/the-transformation-of-the-american-dream.html. Accessed 4 Aug

Sirmans G, Gatzlaff D, Macpherson D (2008) Horizontal and vertical inequity in real property taxation. J Real Estate Lit 16(2):167–180

Slack E (2016) Sustainable development and municipalities: getting the prices right. Can Public Policy 42(1):S73–S78

Slack E, R Bird (2014) The political economy of property tax reform. OECD Working Papers on Fiscal Federalism 18. OECD, Paris (http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/taxation/the-political-economy-of-property-tax-reform_5jz5pzvzv6r7-en)

Sommer M, Kratena K (2017) The carbon footprint of European households and income distribution. Ecol Econ 136:62–72

Spinney J, Kanaroglou P (2012) Municipal taxation and social exclusion: examining the spatial implications of taxing land instead of capital. Can J Urb Res 21(1):1–23

Springer S (2015) Postneoliberalism. Rev Radic Political Econ 47(1):5–17

Standing G (2011) The Precariat: the new dangerous class. Bloomsbury, New York

Stephan A, Crawford R (2016) The relationship between house size and life cycle energy demand: implications for energy efficiency regulations for buildings. Energy 116:1158–1171

Stewart W (1909a) Land tenure and land monopoly in New Zealand: I. J Polit Econ 17(2):82–91

Stewart W (1909b) Land tenure and monopoly in New Zealand: II. J Polit Econ 17(3):144–152

Sunderman M, Birch J, Cannaday R, Hamilton T (1990) Testing for vertical inequity in property tax systerns. J Real Estate Res 5(3):319–334

Tencer D (2015) Soaring house prices are widening inequality, so raise property taxes, Stiglitz tells Canada. Huffington Post (Canada Business). http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2015/11/24/joseph-stiglitz-inequality-canada-property-taxes_n_8639052.html. Accessed 24 Nov

Thakur P, S. Chen (2013) Singapore to raise property tax rates for luxury homeowners. ETF Advisor. http://www.etfa-mag.com/news/singapore-to-raise-property-tax-rates-for-luxury-homeowners-13456.html. Accessed 26 Feb

The Economist (2015) Assessing the assessments. https://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21669962-housing-taxed-more-heavily-new-york-londonunless-youre-rich-assessing. Accessed 3 Oct

Theodorides C (2016) Immovable property tax 2016. Cyprus Property News Magazine. http://www.news.cyprus-property-buyers.com/2016/07/14/immovable-property-tax-2016/id=00151477. Accessed 14 June

Tomlinson P (2013) Singapore’s property taxes aim to deter foreign speculation South China Morning Post. http://www.scmp.com/property/international/article/1189254/singapore-property-taxes-aim-deter-foreign-speculators. Accessed 13 March

Tukker A, Cohen M, Hubacek K, Mont O (2010) The impacts of household consumption and options for change. J Ind Ecol 14(1):13–30

United Nations Environment Program (2010) Assessing the environmental impacts of consumption and production: priority products and materials. A report of the Working Group on the Environmental Impacts of Products and Materials to the International Panel for Sustainable Resource Management by Hertwich E, van der Voet E, Suh S, Tukker A, Huijbregts M, Kazmierczyk P, Lenzen M, McNeely J, and Moriguchi Y. UNEP, Paris. http://www.unep.fr/shared/publications/pdf/dtix1262xpa-priorityproductsandmaterials_report.pdf

Urbina I (2016) Perils of climate change could swamp coastal real estate. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/24/science/global-warming-coastal-real-estate.html. Accessed 24 Nov

van Alphen Fyfe M (2016) Woe unto them that lay field to field: closer settlement in the early liberal era. Vic Univ Wellingt Leg Res Pap (https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2814376

Van Wychen J (2008) How to make the property tax more progressive. MinnPost. https://www.minnpost.com/community-voices/2008/05/how-make-property-tax-more-progressive. Accessed 12 May

von Glahn R (2011) Book review of negotiating urban space: urbanization and late Ming Nanjing by Si-yen Fei. Harv J Asiat Stud 71(1):209–220

Weber C, Matthews H (2008) Quantifying the global and distributional aspects of American household carbon footprint. Ecol Econ 66(2–3):379–391

Wilson A, Boehland J (2005) Small is beautiful: US house size, resource use, and the environment. J Ind Ecol 9(1–2):277–287

Yahya Y (2013) Budget 2013: more progressive property tax rates for Singaporean households. The Straits Times. http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/budget-2013-more-progressive-property-tax-rates-for-singaporean-households-0. Accessed 25 Feb

Zech C (1980) Fiscal effects of urban zoning. Urb Aff Q 16(1):49–58

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Handled by Vinod Tewari, The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI), India.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cohen, M.J. Reforming local public finance to reduce resource consumption: the sustainability case for graduated property taxation. Sustain Sci 14, 289–301 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0598-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0598-6