Abstract

During imminent threat emergencies, an authorities’ ability to communicate with the public and provide them with timely and accurate information is imperative. Wireless emergency alerts (WEAs) sent via the integrated public alert and warning system are short message alerts that authorities can send to devices in specific geographical regions during times of imminent threat. These messages give authorities the ability to distribute important information in a timely manner to those who need it most. In September 2016, the Federal Communications Commission adopted rules to strengthen the WEA system, including increasing the character limit of WEAs from 90c. to 360c. for 4G LTE and newer devices. Implemented in December 2019, the additional 270c. provide authorities with an opportunity to share supplemental and clarifying information in WEA messages. Current research regarding best practices for creating short message alerts was reviewed and analyzed to develop evidence-based guidance, and in turn, create a tool that, with only fifteen user-prompts, can be used to rapidly create effective and informative wildfire evacuation messages of up to 360c. A message creator can use this tool by selecting or entering responses to each of the fifteen prompts. This article presents a bridge between social science research on short message alert effectiveness and the practical generation of messages during imminent threat emergencies. Future research is proposed to develop this tool for purposes other than evacuation, for hazards other than wildfires, and for systems other than WEA (e.g., mass notification systems).

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Imminent threat emergencies are rapid onset events that pose immediate and grave danger to a specific region(s) or group(s) of people. These hazards can be categorized as either natural (e.g., earthquakes, landslides, wildfires), human caused (e.g., active shooter, terrorism), or technological (e.g., biological/radiological hazard, industrial accident). During these events, providing information to the public is of the utmost importance. If people do not perceive that they have full and accurate information, they are likely to engage in knowledge seeking [1, 2]—i.e., searching for additional or clarifying information that they feel is necessary for making decisions and taking protective actions. This behavior can delay movement to safety and increase the likelihood of encountering danger, which can lead to injuries and even death.

Short message platforms are communication channels that emergency personnel can use to quickly provide information to the public. These messages are defined as ‘short’ because they are limited in the number of characters allowed; where each letter, space, and punctuation mark is considered a single character. An example of a short message platform is wireless emergency alerts (current limit 360c., legacy limit 90c.) that are sent via the integrated public alert and warning system (IPAWS). Wireless emergency alerts (WEAs) are one of multiple means by which authorities can send simultaneous alerts and warnings via the IPAWS. Communities may also choose to utilize subscription and/or application-based platforms (e.g., Everbridge or Twitter), making WEA one of several potential short message types in a community’s alerting network.

The WEA was created in 2012 by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), in partnership with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and U.S. wireless carriers, as a way to warn the public about dangerous weather, missing children, and other critical situations [3]. Authorized national, state, or local government authorities have the ability to create and disseminate information in the form of WEAs via IPAWS [3]. The messages are geo-targeted; meaning authorities can selects the region(s) of users that will receive the message, as long as the user’s wireless carrier participates in the program and his/her device is WEA-enabled [4]. Those outside the geographical warning area will not receive the message. WEAs can also be highly effective during times of emergency because they use a different delivery method than SMS messages (i.e., text messages) [3].

According to FEMA there are more than 1100 federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial authorities that have the ability to send WEA messages [5]. However, these authorities cannot directly send their messages to WEA-capable devices and must use one of twenty-five currently available FEMA-approved alert origination software [6]. These software systems use the free IPAWS for messages to be “authenticated, validated and delivered to FEMA’s Alert Gateway” [4]. From the alert gateway, messages are disseminated to multiple public alerting systems, one of which is WEA.

It is the responsibility of the alerting authority to create WEA messages before they are entered into the alert origination software. There are currently two main methods used to develop WEA messages. During planning, messages may be created (as templates) that require only incident specific information to be updated or entered before dissemination can occur (e.g., time, date, etc.). Challenges arise with this method because it is difficult to generate templates for every situation that might occur. Authorities can also create messages ‘free-form’ as an incident is unfolding. This may lead to delays in message development/dissemination as well as errors and/or confusing or misleading statements.

The FCC has adopted multiple changes to WEAs since 2016, including an increase in the character limit.Footnote 1 As of December 2019, 4G LTE and newer devices support up to 360c. messages compared to legacy messages (still supported on 3G and older mobile devices) that are 90c. This shift from 90c. to 360c. messages poses a unique set of benefits and challenges. It has been observed that longer messages can have a positive impact on the message receivers’ comprehension, personalization, and decision-making [7,8,9,10]; however, there are currently few resources available to alerting authorities that provide education or guidance on how to utilize these additional 270c. [11, 12]. Alerting authorities may be slow to adopt and take advantage of this character increase because of unfamiliarity with creating messages longer than 90c. Unless those generating templates or free-form messages have had training or completed research on best-practices for short message alerts, the messages might also not be reaching their full potential.

A message creation toolFootnote 2 has been developed based on social science research that assists alerting authorities in writing effective, evidence-based WEA messages of up to 360c. The tool is structured to gather minimal information from a message creatorFootnote 3 through a series of simple prompts to produce a WEA message. While the research and guidance gathered regarding best practices in short message alerting is applicable to all hazards, the tool focuses on generating messages for wildfire evacuations. The potential applications of this tool are using it to generate templates during wildfire planning and/or using it in lieu of ‘free-form’ writing to generate messages as a wildfire emergency is occurring. The following sections of this article present the research methods for tool development, a literature review, an outline of the tool and its components, a case study, and conclude with ideas for future research and tool improvements.

2 Research Methods

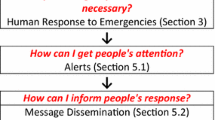

Several databases were consulted to gather research regarding the public’s response to short message alerts and 33 useful publications were identified spanning the disciplines of sociology, psychology, communications, human factors, and engineering. Information was extracted from each publication including: the topic, objectives, research methods, research findings, recommendations based on the findings, and other information that was relevant/potentially useful for introductory or background sections. Information from these sources was reviewed and labeled according to an organizational method that was developed based on the Protective Action Decision Model (PADM). This organizational method was used to understand how the findings applied to each stage of the PADM and how they could be used to increase a message receiver’s attention, understanding, believability, and personalization [11, 12].

To develop the message creation tool, the collected research was reorganized into six categories: message source, hazard identification, hazard location, timeline, guidance, and general. Five of the six categories aligned directly with research on alert and warning messages that has found well-constructed and effective WEA messages contain clear and specific information about five specific topics: the threat, including its likelihood and the severity of its impacts; the populations or geographical areas at risk; the time to take action; recommended protective actions; and the source of the message [13,14,15,16]. The final category, ‘general’, was used for information that pertained to WEA messages as a whole or was applicable to all of the message content sections. This step was completed to see if and how each of the research findings could be applied to the different topics within a short message alert. The intention of this reorganization was to investigate how each of the message topics could be optimized through increasing attention, understanding, believability, and personalization in order to positively impact a message receiver’s decision-making process.

Research was excluded if the findings did not apply to the original development and/or text of a WEA message. For instance, findings about the inclusion of maps within short message alerts [17] and what happened to a message after it was disseminated (e.g., whether or not the information was passed onto someone else) were not incorporated. Annotations were created for each source to identify general information, problems/shortcomings, and key findings. The annotations also included comments about the information’s relationship to other sources, unanswered questions, and other general comments.

A list of key questions a short message alert needs to answer was created and used throughout the tool development process as a reminder of the main purpose of each content section.

-

1.

Who/which agency is sending this message?

-

2.

What is the hazard people are being warned about?

-

3.

What are the potential consequences of this hazard?

-

4.

What is the current location of the hazard?

-

5.

What direction is the hazard moving?

-

6.

What region(s) of people should evacuate?

-

7.

How long does the message receiver have until he/she needs to act?

-

8.

What protective actions should the message receiver be following?

The impact that each piece of information had on the tool was then determined. A list of potential user inputs was created and refined into the fifteen user prompts, relevant to wildfire emergencies, included in the beta tool version. For each of the prompts, the response type required from the message creator was determined including: drop-down (list selection), yes/no, and fill-in (short answer). Next, a menu of potential responses was created with the acknowledgement that each user response impacted the message output in different ways. The interaction between message prompts, user responses, and message section outputs were captured in a series of logic diagrams [18].

Microsoft Excel was used as the platform to build the beta version of the short message creation tool. Length of a specified string functions (i.e., = LEN()) were used when counting characters was necessary. Logic was created using a series data validation ranges and ‘IF’ statements. See [18] for further information regarding the logistics of developing the beta tool. A discussion is provided at the end of this article on future research, including building the tool within other software programs which may be more user-friendly.

A case study was completed based on a WEA message sent during the Thomas Fire to demonstrate the validity and benefits of the message creation tool. This case study includes the following: background information, the original WEA sent, a table summarizing its perceived problems and shortcomings, the message creator responses used to generate the new 360c. message, an analysis of the tool-generated message compared to the original message, and potential problems/shortcomings of the message creation tool and tool-generated message.Footnote 4

3 Literature Review

This section provides a review of the literature, including a discussion on the Protective Action Decision Model (PADM), and current guidance on writing effective short message alerts.

3.1 Protective Action Decision Model

The PADM is a multi-stage model developed by Lindell and Perry [19] that describes people’s responses to environmental hazards and disasters. The model identifies the steps a person takes from the time some external piece of information is learned (e.g., environmental cues, social cues, alert and warning messages, etc.), to the time that an individual makes a decision regarding a necessary protective action.

The model includes three pre-decisional processes (exposure, attention, comprehension) that identify the amount of external information an individual was exposed to along with the level to which they understood it. Next, the model identifies three core perceptions (threat, protective action, stakeholder) that dictate how an individual perceives the hazard they are facing, the actions or resources they may need to respond to the hazard (i.e., hazard-adjustment), and the roles and responsibilities of those involved, including themselves. These pre-decisional processes and core perceptions influence an individual’s decision making and overall behavioral response to an event.

The model identifies three behavioral responses; information searching, protective response, and emotion-focused coping. During the process if individual is unsure of the information they received or how to proceed, he/she may search for additional information to fill the gaps. This may involve consulting other sources, such as websites and/or friends and family, and is known as the milling process [1, 2, 20].

Short messages, along with other types of cues, are inputs for an individual’s decision-making process. Based on this model, before an individual can take protective action, they must receive the alert/warning message(s), pay attention to and comprehend it. Additionally, during this process, people may ask themselves whether there is a credible threat or not, and finally if they perceive a risk to themselves, or to their loved ones. If at any time in this process, people are unable to comprehend the message and/or are unable to answer the threat or risk questions, they will engage in information seeking, which can delay their movement to safety.

The following is a description of how the tool accounts for each stage in the PADM:

-

Message receipt: the tool assumes the message receiver has a WEA-capable device and is located in the area of impact.

-

Exposure/attention paid: the tool assumes that the message receiver notices the WEA and chooses to read it; the tool emphasizes certain parts of the message to prompt greater attention.

-

Comprehension: the tool aims to include text that is easily understood by the larger U.S. population, it assumes the message receiver has a basic knowledge of the English language and does not have any physical or cognitive disabilities that would prevent him/her from reading and understanding the message.Footnote 5

-

Threat perception: the tool assumes messages are stand-alone units that do not rely on any additional external cues or an individual’s attributes to help influence the message receiver’s threat perception. Therefore, the tool provides ways to establish a clear description of the hazard; which can influence threat perception [21].

-

Risk perception: the tool accounts for the fact that a message must convince the reader that the hazard being described is not only real but can have significant and lasting consequences upon him/her, potentially negative if they do not act [22]. The tool also accounts for the urgency under which the population may be required to act in certain types of imminent threat emergencies.

-

Protective action decision and subsequent action: the tool aims to include specific text instructing the message receiver on the actions that should be taken to achieve protection.

Recommendations and guidance on creating short message alerts based on the stages of the PADM [11, 12] are shown in Table 1.

3.2 Content of an Effective Short Message

To generate an effective short message alert that increases the probability an individual will take protective action, the inclusion of five types of information have been found necessary [13, 23, 24]:

-

Source (i.e., the organization or entity who is sending the message),

-

Guidance (i.e., the protective actions that the public should be taking in response to the message),

-

Hazard (i.e., the event that has happened/is about to happen and the threat it poses to the public),

-

Timeline (i.e., when the event will occur and when the public needs to act),

-

Location (i.e., the region(s) the hazard is impacting and the region(s) of people who are at risk).

For messages of 280c. or greater, the following order has been found most effective in improving an individual’s understanding, belief, and decision making: source, hazard, location, time, guidance [7, 12]. Below, content sections of the short message (in that order) are addressed individually and for each, key findings, recommendations, and supporting literature have been provided.

Some studies [15, 39] have shown that even without complete short message alerts, people were still likely to take appropriate protective actions (i.e., evacuation). These decisions are likely based on supplemental information gathered while milling, rather than incomplete messages alone. Therefore, by providing “complete” messages with the necessary content, it is likely that even more people will take appropriate protective actions, and they will take them sooner (i.e., with less milling behavior).

4 WEA Message Creation Tool

Figure 2 displays an interface of the message creation tool. At the top of the interface, a cell named ‘Message:’ appears and the adjacent cell is where the message forms as the user enters his/her responses. At the commencement of message creation, this cell is blank. Directly below this cell is another titled ‘Characters Left:’. The adjacent cell is used to inform the message creator of the number of characters remaining, beginning at 360 and decreasing as he/she responds to the prompts. Below each prompt, there is a phrase that indicates how the message creator should respond, (e.g., ‘select’ for drop-down or yes/no menus, ‘enter’ for the user to fill-in their response). In the column to the right, the message creator will either select or enter their response to each prompt.

Each of the user prompts was developed based on social science research and aims to answer one of the 8 key questions originally posed in Sect. 2. Doermann [18] presents an in-depth discussion of each of the prompts/responses and the research justification for their inclusion. Specific decisions regarding word choice (e.g., using the word ‘home’ instead of ‘house’), punctuation (e.g., encapsulating abbreviations in parenthesis), and capitalization (e.g., why only certain words are capitalized) are also included in [18] and omitted in this article. Sections 4.1–4.5 provide each of the content sections along with their corresponding prompts, potential user responses, and required response types.

4.1 Message Source

-

Prompt 1: What agency should be listed as the source of this message? (fill-in)

User response 1: Response 1

-

Prompt 2: Does this agency use an acronym that is more common than its official title? (Yes/No)

User response 2a: No

User response 2b: Yes

-

Prompt 3: (If user response 2a) Prompt not applicable. Continue to next prompt.

-

Prompt 3: (If user response 2b) What is the acronym used by this agency? (fill-in)

User response 3: Response 3

4.2 Hazard Identification

-

Prompt 4: What type of emergency is happening or about to happen? (drop-down)

User response 4a: Wildfire Emergency

-

Prompt 5: What wildfire consequences should the public be aware of? “Wildfires can…” (drop-down, fill-in); two possible options can be included hereFootnote 6

User response 5a: burn down homes/other structures

User response 5b: block roads/evacuation routes

User response 5c: cause injury/death

User response 5d: other (35c. limit)Footnote 7; with subsequent (fill-in) requiredFootnote 8

4.3 Hazard Location

-

Prompt 6: Which will be used to identify the current location of the hazard? (drop-down)

User response 6a: well-known landmark(s)

User response 6b: town/city/county (all or portion)

User response 6c: major road(s)/intersection(s)

-

Prompt 7: The hazard is located (in/near/between) which user response 6(a-c)? (drop-down, fill-in)

User response 7-1a: in

User response 7-1b: near

User response 7-1c: between

User response 7-2: Response 7-2 (fill-in)

-

Prompt 8: Which will be used to identify the direction the fire is spreading? (drop-down)

User response 8a: well-known landmark(s)

User response 8b: town/city/county (all or portion)

User response 8c: major road(s)/intersection(s)

-

Prompt 9: What is the name of the user response 8(a-c) that the fire is moving towards? (fill-in)

User response 9: Response 9

-

Prompt 10: Is there a specific region of people who should evacuate? (drop-down)

User response 10a: No, everyone receiving this message should evacuate

User response 10b: Yes

-

Prompt 11: (If user response 10a) Prompt not applicable. Continue to next prompt.

-

Prompt 11: (If user response 10b) People located (in/near/between) which region(s) should evacuate? (drop-down, fill-in)

User response 11-1a: in

User response 11-1b: near

User response 11-1c: between

User response 11-2: Response 11-2 (fill-in)

4.4 Event Timeline

-

Prompt 12: When should people take action? (drop-down)

User response 12a: Now

User response 12b: Before ##Footnote 9 (AM/PM) (drop-down)

4.5 Protective Action Guidance

-

Prompt 13: What is the main purpose of this message? (drop-down)

User response 13a: Evacuation

-

Prompt 14: What specific actions should people receiving this message take? (drop-down, fill-in)

User response 14a: Do not delay to pack belongings.

User response 14b: other (35c. limit)8, with subsequent (fill-in) required9

-

Prompt 15: Where should people go for updates?

User response 15a: none

User response 15b: Check {website} for updates.

User response 15c: Call {phone number} for updates.

5 Case Study: The Thomas Fire

A message written with a 360c. limit versus a 90c. limit may be viewed as superior without investigation because of its extended length and ability to include more information and details. However, if used improperly, the additional information may confuse the message receiver and cause delays in their protective action taking (i.e., increase milling time). The tool assists a message creator in generating an effective and useful message with fifteen basic prompts—ensuring the information included addresses the five types of content necessary and contains supplemental information that is relevant and useful to the message receiver.

5.1 Original Message Analysis and Research

For this case study, the WEA message shown in Fig. 1 sent during the Thomas Fire will be investigated. The fire began on December 4, 2017 around 18:28 [40] and is known as one of the largest wildfires in California history. According to Cal Fire [40], the Thomas Fire’s cause was downed power lines in an unincorporated area north of the City of Santa Paula [41]. It grew west due to strong Santa Ana winds—spreading over the Ventura County line into Santa Barbara County [42]. It burned over 281,800 acres and destroyed over 1060 structures before it was 100% contained. An estimated $177 million in damages were reported and the fire is responsible for two fatalities, one civilian during evacuation and one fire fighter battling the blaze [43]. According to a FEMA briefing on May 23, 2018, over 90,000 + people were under mandatory and voluntary evacuation orders throughout the course of the fire [44]. Mandatory evacuation areas included parts of the City of Santa Barbara, Montecito, Summerland, City of Ventura, and unincorporated areas of Fillmore and Ventura Counties [45].

Original WEA sent [49]

According to the FEMA WEA FRW (Fire Warning) list [46], this message was sent at 07:21 on December 5, 2017 approximately 12 h after the start of the fire. The original message contains the exact text listed in [46]. It was sent using all uppercase letters and is exactly 90c. (the character limit for all WEAs at the time the message was sent). This message was sent to Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) Code 06,111; a County FIPS code for Ventura County [47]. FIPS is a set of codes issued for the identification of specific geographic regions. This system is used by IPAWS as a method to identify a geographic warning area [48]; meaning the message was issued to the geographic area of Ventura County.Footnote 10

An ‘IPAWS Non Weather’ blog that compiles “IPAWS Public Alerts from Alerting Authorities except the National Weather Service” confirms the WEA text recorded in the FEMA list, including the ‘F’ at the end of the message [49, 50]. The blog ‘description’ listed reads, “FAST MOVING BRUSH FIRE BETWEEN SANTA PAULA, VENTURA, OJAI – GO TO READYVENTURACOUNTY.ORG FOR INFO.” This description is 98c.–8 above the WEA limit at the time the message was sent. The messages match verbatim except for the final 8 characters. The inference can be made that the description was the intended full message, but the IPAWS system eliminated the last 8 characters (i.e., “OR INFO.”) prior to its distribution. One possible reason for this error is the message creator, working quickly, forgot to check the character count before sending the message. If the WEA sent was not meant to contain the last two words of the description, it is more than likely the “F” would have been removed also (Table 2).

The website “READYVENTURACOUNTY.ORG” was established by the Ventura County Sheriff’s Office of Emergency Services. Using the Way Back Machine, a site that archives internet pages, the interface of this site on December 5, 2017 at 13:50 was accessed. The site provided information such as the location of the fire, the direction of spread, the resources being put in place to control the fire, the proclamation of a local emergency, the size and containment level of the fire, mandatory and voluntary evacuation zones, a map with an overlay of the fire and evacuation zones, road and school closures, shelter locations, and donation information. While this information holds importance, some of it can be viewed as extraneous (e.g., resources and personnel being deployed to contain the fire) for those searching for what initial protective actions they should be taking. Some of this important information may be better suited for situational briefings or secondary webpages, while the homepage is reserved for essential information needed by those evacuating.

Table 3 deconstructs the original message into the five necessary content sections and provides comments regarding the problems and shortcoming of each section as well as the message in its entirety.

5.2 Tool-Generated Message

To generate a new message for Ventura County during the Thomas Fire using the message creation tool, inputs for each of the user prompts were selected based on the original message and supplemental research.Footnote 11 Note that those generating the original WEA message were likely using all accessible information and it is possible the tool-generated message is informed by knowledge that was not available at that time. Figure 2 shows the interface of the tool after user responses to all prompts were selected. The 357c. message generated can be seen in Fig. 2 or under ‘Tool-generated message’ in the following section.

5.3 Comparison of Original and Tool-Generated Messages

The purpose of this comparison is to explain the value added by the message creation tool and additional 270c.Footnote 12 In Fig. 3,Footnote 13 the text of the original and tool-generated messages is identified according to the necessary content sections.

The original message is missing two of the five necessary content sections (source and timeline) and only partially addressed two of the other three (location and guidance). The tool-generated message includes information about all the content sections as well as supplemental information to increase the message receiver’s belief, understanding, and personalization.

The eight questions (originally posed in Sect. 2) displayed in Table 4 were developed to indicate major points of potential confusion in a short message alert, where the message receiver may need clarification. The five questions without the ‘*’ are associated with the five necessary content types. The three questions with the ‘*’ were developed to add additional or clarifying information to the message. In Table 4, the questions have been applied to each message and responses have been written using only the information available in the original and tool-generated short messages, respectively.

Additional to the missing content sections, another concern with the original message is the letter ‘F’ that appears at the end, most likely due to the final characters of the message being truncated. With the message creation tool, the character limit is displayed, and the message can be altered after all prompts have been responded to if it is found to be over the character limit. This feature aims to eliminate the problem of creating messages that are too long.

Finally, the original message appeared in all capital letters and no additional justification has been found to indicate why this was done. No research has been found that disputes the use of all capital letters and/or identifies this method as ineffective. However, research shows that it is effective to use certain words in capital letters to signify the content of the message or emphasize words or phrases [23]. The message creation tool uses capital letters to signify (e.g., WILDFIRE EMERGENCY) and emphasize (e.g., EVACUATE NOW); drawing the reader’s attention to these two phrases and indicating they are of high importance.

5.4 Limitations

This case study shows that the tool-generated message addresses many of the problems and shortcomings discovered in the original 90c. WEA. The tool-generated 360c. message not only contains all five content types but also additional information that aims to help the message receiver understand, believe, and act upon the message quicker. However, the message creation tool and the tool-generated message contain their own potential shortcomings.

One of the largest perceived challenges of the message was the lack of identification of ‘Santa Paula, Ventura, Ojai’ as either cities or counties. This information is not programmed into the tool and would require the message creator to enter it manually. In this case study, the identification was omitted when entering the response to Prompt 7 due to character limitations. It is possible that this omission has the potential to increase the message receivers’ confusion if there are regions that have the same base name, but one is identified as ‘city’ and another as ‘county’ (e.g., Santa Paula City vs. Santa Paula County). In the beta version of the tool, the message creator could include these identifiers while responding to the prompts and then edit the final message if it exceeded 360c.

The message creation tool allows for multiple evacuation zones to be identified. However, in this scenario, only one was able to be included and additional zones would have caused the message to go over the character limit restriction. This could be a challenge if the message creator wants to identify and evacuate multiple regions within the same message. Additionally, for evacuations the tool does not currently have the ability for the message creator to identify and provide instruction to smaller regions in the hazard area. This could be a challenge for a situation where phased evacuation is desired, and the message creator may need to send cascading messages to provide this instruction.

The perceived evacuation zone identification challenges speak to a larger limitation of the beta message creation tool—lack of flexibility in message content and wording. The tool requires responses to all prompts to ensure the necessary content is included in the message and the pre-programmed ordering of content and punctuation are utilized correctly. This tool is ideal for situations where it is being used to create a “complete” short message alert. In addition to the phased evacuation example, this tool may not be ideal for follow-up or clarifying messages where regions have already received a “complete” initial message. In these secondary messages, creators may choose to not include all five content types. For instance, in a message used to update evacuees about a wildfire’s location, he/she may choose not to include the consequences of the wildfire if they were included in the primary message. Using the message creation tool, this could be accomplished by responding to all of the prompts and then editing the tool-generated message before dissemination. Future research and development might help to mitigate these limitations and other that are identified in the beta tool version.

6 Conclusions

WEAs are a form of short message alert that can be sent using IPAWS during imminent threat emergencies. Currently, WEAs can be written free-form as an emergency is happening or using templates created before an emergency occurs. The FCC mandates implemented in December 2019 increase the WEA character limit from 90c. to 360c. for 4G LTE and newer devices. These extra 270c., if used correctly, provide message creators the opportunity to communication important and potentially life-saving information to the public.

Much of the information available to message creators regarding best practices in writing short message alerts is ambiguous and requires interpretation. The message creation tool was designed to assist in generating wildfire evacuation-based WEAs using a series of fifteen prompts. To construct the tool, the currently available research and best practices in short message alerts was collected, analyzed, and implemented. The message creation tool ensures that all necessary information is being included in the message as well as clarifying and useful supplemental information. The message creation tool sets a foundation for the bridge between short message alert research and the practical generation of messages during imminent threat emergencies.

It is important to note that alerting authorities should view WEAs, or any short messaging channel, as one of many techniques available for information dissemination. In the process of developing the message creation tool, the authors assumed that the message receiver only perceives and pays attention to the WEA alert. This assumption was made to ensure that the WEA alert contained all necessary information that could be feasibly included in up to 360c. In this case, IF the message receiver does only heed the short message alert, they are more likely to respond in a safe and effective manner, and potentially sooner than those who did not. With that said, research on public response to alerts and warnings agree that the public is likely to engage in milling behavior even after a “complete” warning message is provided by perceiving environmental cues, talking with others about the threat and risk, and/or receiving clear, consistent, and accurate messages from other sources [19, 51]. The goal is that by providing complete, evidence-based short message alerts, time spent in the milling process will be reduced and the likelihood of individuals taking protective action will be increased, in turn, decreasing deaths and injuries in wildfire events.

Key contributions of this work include: (1) an analysis of current research regarding best practices in short message alerts including a discussion of potential problems/shortcomings and key findings/recommendations, (2) investigation of research-based guidance and its application to the content sections of a short message alert, (3) and the development of fifteen user prompts based on the aforementioned research and analysis that, when completed, gather information to generate wildfire evacuation-based emergency alerts. The following section identifies topics for future research and potential improvements that could be made to future versions of the message creation tool.

7 Future Research and Tool Improvements [18]

While completing this work, potential area for future research and/or tool improvement were identified including:

Development of the tool for purposes other than evacuation In the beta tool, evacuation is the only purpose that can be selected (Prompt 13). Future versions of the tool could allow the message creator to select the other purposes (e.g., shelter-in-place).

Development of the tool for hazards other than a wildfire While individually, not all beta version prompts are wildfire specific, they were compiled to develop wildfire evacuation-based messages. Future versions of the tool can be expanded to include other emergencies (e.g., tornado emergency, flash flood, active shooter, and bomb threat).

Development of the tool for systems other than WEA The message creation tool was developed with the focus of WEA messages (360c. max). Future versions could expand this concept for other short message alerting systems, such as Twitter. In an alternate form, the tool could be used to develop templates for mass notification alerts or warnings where only a few pieces of information would need to be updated or entered during an emergency. The tool could also potentially be used to generate messages in real time if a building has designated emergency communication personnel. Future versions could be developed for any situation where the concept of a tool that generates messages that auto-incorporate research and known best practices would be beneficial.

Improvement of the tool and tool-generated messages wording and grammar Future versions of the tool might allow for more flexibility in wording, potentially through short free-hand responses that have guiding questions. Also, future versions might include a spell check feature, such as a pop-up that appears after the prompts have been filled out to alert the message creator of misspelled words. Finally, the tool has built in punctuation and does not account for repeats in punctuation marks. Future versions of the tool may be able to account for this and ensure punctuation is not being repeated.

Validation testing of the tool’s practicality It is believed that the tool offers benefits such as aiding a message creator in generating messages quicker than he/she would be able to if writing them free-form. Validation testing would be needed to prove this and determine other benefits the tool provides.

Validation testing of the tool-generated messages The tool-generated message was analyzed for benefit through its comparison to a 90c. WEA and its ability to reply to the eight questions developed as the main questions a wildfire evacuation-based message should answer. Validation testing of messages would be necessary to analyze other benefits of the message that are hypothesized, such as increased readability and understanding.

Notes

For a list of other WEA enhancements, please visit https://www.fema.gov/integrated-public-alert-warning-system.

Message creation tool (i.e., the tool) refers to the developed program that can be used to generate messages.

Message creator refers to the individual(s) who is utilizing the tool to generate messages.

Two additional case studies can be found in [18].

Note that the future research section lists ways to expand the beta version of the tool, e.g., to include multiple languages.

On the second choice, the user can select “none” and include only one wildfire consequence in the message.

The limit of 35c. was set so the message creator could provide a complete response with limited concern that the 360c. threshold for the message would be surpassed.

Meaning the message creator has chosen to not use of the one provided responses and must manually enter the phrase they want included in the message.

Note ## includes a drop down of numbers 1-12.

Geographical warning areas may also be identified by other methods such as the triangulation of cell phone towers.

Note the message creation tool aligns with social science findings on risk communication during disasters and the value of the tool and tool-generated message are based on scientific findings regarding preferred message content. Further testing would be needed to assess whether they would have led to different or better outcomes in the Thomas Fire or other/future fires.

This message is the output of the message creation tool and no post-tool editing has been completed. Any punctuation, organization, and/or additional verbiage not in the user responses is coded into the message creation tool.

References

Aguirre BE, Wenger D, Vigo G (1998) A test of the emergent norm theory of collective behavior. Sociol Forum 13(2): 301–320

Turner RH, Killian LM (1972) Collective behavior. Prentice Hall, Inc, New Jersey

Federal Communications Commission (2018) Consumer guide: wireless emergency alerts (WEA). https://www.fcc.gov/sites/default/files/wireless_emergency_alerts_wea.pdf. Accessed 10 Mar 2019

Federal Communications Commission (2018) FCC 18-4 SECOND REPORT AND ORDER AND SECOND ORDER ON RECONSIDERATION. January 31, 2018. Accessed 7 Mar 2019 https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-18-4A1.pdf

Witmer W (2017) Integrated public alert and warning system (IPAWS). Prepared for the radiological preparedness conference. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). https://www.nist.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2017/08/24/5-ipaws_for_nacwir_mtg_24aug2017.pdf. Accessed 12 Apr 2019

Federal Emergency Management Agency (2016) Alert origination software providers that have successfully demonstrated their IPAWS capabilities. https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/25916. Accessed 21 May 2019

Wood M, Bean H, Liu B, Boyd M (2015) Comprehensive testing of imminent threat public messages for mobile devices: updated findings. College Park: National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism

Bennett DM (2015) Gaps in wireless emergency alert (WEA) effectiveness. Public Administration Faculty Publications, p 82. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/pubadfacpub/82

Erdogmus H, Griss M, Iannucci B, Kumar S, Falcão J, Jauhri A, Kovalev M (2015) Opportunities, options, and enhancements for the wireless emergency alerting service. Technical report CMU-SV-15-001. Carnegie Mellon University

Daly BK, Gerber M, Anderson WB, Bhatia K, Cox C, Davis JS, Hodan C (2014) The communications security, reliability and interoperability council, working group 2 report. Federal Communications Commission, Washington, DC

Kuligowski ED, Doermann J (2018) A review of public response to short message alerts under imminent threat. NIST technical note (TN) 1982. National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg. https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.TN.1982

Sutton J, Kuligowski ED (2019) Alerts and warnings on short message channels: guidance from an expert panel process. Nat Hazards Rev 20(2):04019002

Mileti DS, Sorensen JH (1990) Communication of Emergency Public Warnings. ORNL6609. National Laboratory, Oak Ridge

Sorensen JH (2000) Hazard warning systems: review of 20 years of progress. Nat Hazards Rev 1(2):119–125. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1527-6988

Lindell MK, Prater CS, Gregg CE, Apatu E, Huang S-K, Wu H-C (2015) Households’ immediate responses to the 2009 American Samoa earthquake and tsunami. Int J Disast Risk Reduct 12:328–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2015.03.003

Lindell MK, Huang S-K, Prater CS (2017) Predicting residents’ responses to the May 1–4, 2010, Boston water contamination incident. Int J Mass Emerg Disast 35(1):84–113

Liu BF, Wood MM, Egnoto M, Bean H, Sutton J, Mileti D, Madden S (2017) Is a picture worth a thousand words? The effects of maps and warning messages on how publics respond to disaster information. Public Relat Rev 43(3):493–506

Doermann JL (2019) Development of a research-based short message creation tool for wildfire emergencies. University of Maryland, College Park

Lindell MK, Perry RW (2012). The protective action decision model: theoretical modifications and additional evidence. Risk Anal Int J 32(4):616–632

Wood MM, Mileti DS, Bean H, Liu BF, Sutton J, Madden S (2018) Milling and public warnings. Environ Behav 50(5):535–566

Bean H, Liu BF, Madden S, Sutton J, Wood MM, Mileti DS (2016) Disaster warnings in your pocket: How audiences interpret mobile alerts for an unfamiliar hazard. J Contingencies Crisis Manag 24(3):136–147

Bean H, Sutton J, Liu BF, Madden S, Wood MM, Mileti DS (2015) The study of mobile public warning messages: a research review and agenda. Rev Commun 15(1):60–80

Sutton J, Spiro ES, Johnson B, Fitzhugh S, Gibson B, Butts CT (2014) Warning tweets: Serial transmission of messages during the warning phase of a disaster event. Inf Commun Soc 17(6):765–787

Mileti DS, Peek L (2001) The social psychology of public response to warnings of a nuclear power plant accident. J Hazard Mater 75:181–194

Liu BF, Fraustino JD, Jin Y (2015) How disaster information form, source, type, and prior disaster exposure affect public outcomes: jumping on the social media bandwagon? J Appl Commun Res 43(1):44–65

Sutton J, Palen L, Shklovski I (2008) Backchannels on the front lines: emergent use of social media in the 2007 Southern California fire. In: Proceedings of information systems for crisis response and management conference (ISCRAM), Washington DC

Wei H-L, Lindell MK, Prater CS, Wei J, Wang F, Ge YG (2018) Perceived stakeholder characteristics and protective action for influenza emergencies: a comparative study of respondents in the United States and China. Int J Mass Emerg Disast 36(1):52–70

Sutton J, Woods C (2016) Tsunami warning message interpretation and sense making: focus group insights. Weather Clim Soc 8(4):389–398

Bean H, Liu BF, Madden S, Mileti DS, Sutton J, Wood MM (2014) Comprehensive testing of imminent threat public messages for mobile devices. National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism. University of Maryland, College Park

Cao Y, Boru BJ, McNeill IM (2016) Is a picture worth a thousand words? Evaluating the effectiveness of maps for delivering wildfire warning information. Int J Disast Risk Reduct 19:179–196

Kuligowski ED, Omori H (2014) General guidance on emergency communication strategies for buildings, 2nd edn. NIST technical note (TN) 1827. National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg. https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.TN.1827

Hui C, Tyshchuk Y, Wallace WA, Magdon-Ismail M, Goldberg M (2012) Information cascades in social media in response to a crisis: a preliminary model and a case study. In: Proceedings of the 21st international conference on world wide web, ACM, pp 653–656

Sutton J, League C, Sellnow TL, Sellnow DD (2015) Terse messaging and public health in the midst of natural disasters: the case of the Boulder floods. Health Commun 30(2):135–143

Woody C, Ellison R (2014) Maximizing trust in the wireless emergency alerts (WEA) service. Software Engineering Institute. Carnegie Mellon University. No. CMU/SEI-2013-SR-027

Temnikova I, Vieweg S, Castillo C (2015) The case for readability of crisis communications in social media. In: Proceedings of the 24th international conference on world wide web. ACM, pp 1245–1250

National Research Council (2013) Public response to alerts and warnings using social media: report of a workshop on current knowledge and research gaps. The National Academies Press, Washington DC. https://doi.org/10.17226/15853

Uzzell D (2012) AMBER alert best practices. US Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Washington, DC

Lindell MK, Perry RW (1987) Warning mechanisms in emergency response systems. Int J Mass Emerg Disast 5:137–153

Lindell MK, Murray-Tuite P, Wolshon B, Baker EJ (2019) Large-scale evacuation: the analysis, modeling and management of emergency relocation from hazardous areas. Taylor & Francis, New York

CAL FIRE (2019) THOMAS FIRE. http://cdfdata.fire.ca.gov/incidents/incidents_details_info?incident_id=1922. Accessed 1 Apr 2019

City of Ventura Emergency Operations Center (2018) Thomas fire after-action review/improvement plan (AAR/IP). https://www.cityofventura.ca.gov/DocumentCenter/View/16058/Thomas-Fire-After-Action-Review?bidId. Accessed 7 Apr 2019

KPCC (2017) Thomas fire grows to 115,000 acres, destroying 439 homes and buildings. Southern California Public Radio (SCPR). https://www.scpr.org/news/2017/12/07/78629/101-freeway-closed-as-thomas-fire-grows-to-96-000/. Accessed 5 Apr 2019

Helsel P (2017) Southern California’s Thomas Fire now largest in state history. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/western-wildfires/southern-california-s-thomas-fire-now-largest-state-history-n832296. Accessed 1 Apr 2019

Federal Emergency Management Agency (2018) THOMAS FIRE BRIEFING. https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/1526574011770-6a3afb18c82beaf881650ae12cfe9891/ThomasFireBriefingNAC_508.pdf. Accessed 1 Apr 2019

Ferreira G (2017) Mandatory and voluntary evacuations for the Thomas Fire. THE TRIBUNE. https://www.sanluisobispo.com/news/state/california/fires/article190237219.html. Accessed 3 Apr 2019

Federal Emergency Management Agency (2018) List of WEA FRW messages sent Mar–Dec 2017. Accessed at NIST.

United States Department of Agriculture (2019) County FIPS codes. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/national/home/?cid=nrcs143_013697. Accessed 28 Apr 2019

Federal Emergency Management Agency (2016) Integrated public alert and warning system (IPAWS) glossary. https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/1452627256761-baf3142e9efc593fe2e633ad53c0980f/IPAWS_Glossary_2016.pdf. Accessed 1 Apr 2019

IPAWSNONWEATHER (2019) Alert: firewarning. http://ipawsnonweather.alertblogger.com. Accessed 15 May 2019

St. John P (2017) Alarming failures left many in path of California wildfires vulnerable and without warning. Los Angeles Times. Accessed 15 May 2019

Lindell MK (2018) Communicating imminent risk. In: Rodríguez H, Donner W, Trainor J (eds) Handbook of disaster research. Springer, New York

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Doermann, J.L., Kuligowski, E.D. & Milke, J. From Social Science Research to Engineering Practice: Development of a Short Message Creation Tool for Wildfire Emergencies. Fire Technol 57, 815–837 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10694-020-01008-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10694-020-01008-7