Abstract

This study assesses prevalence of substance use, and the impact of housing instability. and independence preparation on substance use in two samples: youth currently in-care and former foster youth. Both samples were from a mid-Atlantic state with youth currently in-care residing in rural jurisdictions and former foster youth residing in the state’s largest urban jurisdiction. A cross-sectional design utilizing paper and web-based surveys was used to collect data. Findings indicate youth in-care are consuming substances that are on average with national prevalence statistics. However, former foster youth are consuming substances at alarmingly high rates well above the national prevalence. A high rate of housing instability after leaving child welfare was reported for former foster youth. In addition, greater preparation for independence among former foster youth was associated with less substance usage. Implications for social work practice, independence preparation, and life skills classes are presented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Substance use generally tends to increase from adolescence into young adulthood with a peak of use during young adulthood (National Institutes of Health, 2008). Youth with child welfare involvement may be at an increased risk for future substance misuse. The purpose of the current study is to assess substance use prevalence and the experiences of housing instability and independent living preparation for two samples, youth currently in-care and former foster youth.

Substance Use and Child Welfare Involvement

Youth who have a history of maltreatment, including exposure to trauma, abuse, and mental illness, as well as exposure to parental alcohol and drug use are at risk of substance use disorders once they exit from child welfare (see Aarons et al., 2008; Bender, Yang, Ferguson, & Thompson, 2015; Courtney, Terao, & Bost, 2004; Narendorf & McMillen, 2010; Pilowsky & Wu, 2006; Wall & Kohl, 2007). For example, Braciszewski and Stout (2012) completed a systematic review of studies that assessed alcohol and drug use for current and former foster youth. Their review found that estimates of alcohol and marijuana use among current foster youth are roughly equal to that among the normative populations. However, among former foster young adults, lifetime prevalence rates for alcohol and drugs other than marijuana were higher than young adults without foster care histories. Similarly, Casanueva, Stambaugh, Urato, Fraser, and Williams (2014) found that one-third of young adults with foster care histories had no illicit substance use after child welfare involvement, one-third experimented but were not regular users, and roughly one one-third became regular illicit substance users. Other studies comparing substance use among homeless young adults with and without foster care histories found that there was not a significant difference in drug rates among the two populations, but young adults with foster care histories were more likely to have used cocaine and methamphetamines in the past 6-months compared to non-foster youth (Hudson & Nandy, 2012). These studies suggest increased vulnerability for substance usage for former foster youth.

Housing Instability

An additional area that may have an impact on substance usage is homelessness and housing instability. Families who experience homelessness are at risk for child welfare involvement and several children enter child welfare with a history of homelessness and housing instability (Park, Metraux, Broadbar, & Culhane, 2004). Substance use among homeless youth and young adults has been well documented; some research suggests that homeless youth use substances to numb the experience of homelessness and abuse drugs or alcohol at two to three times the rate of non-homeless youth and young adults (Chen, Thrane, Whitbeck, & Johnson, 2006; Thompson, 2004). Previous research suggests that former foster youth experience higher rates of homelessness, housing instability, and reliance on public housing assistance compared to same age peers without foster care histories (Berzin, Rhodes, & Curtis, 2011). Findings from these studies suggests that current and former foster youth may be more vulnerable for housing instability and substance usage.

Preparation for Independence

Preparation for independence provides a potential outlet where current foster youth may be afforded education about substance use. Two pieces of legislation target independence preparation for older youth in child welfare. The 1999 Foster Care Independence Act created the John H. Chafee Foster Care Independence program which provides funding for independence training programs to provide life skills training for youth emancipating from care. The passage of the 2008 Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act (P.L. 110–351) mandated the development of a transition plan for youth aging out of foster care. Transition planning typically addresses housing, health, education, employment, and support and should include youth input. Although youth and young adults likely will have to make decisions around whether to or how to engage in substance use, prevention and risk reduction training related to substance use are not typically explicit in transition planning curriculums. Youth aging out of care require a mastery of independence skills and a mastery of social complexities needed to successfully navigate young adulthood (Cunningham & Diversi, 2012). The transition to young adulthood typically involves a series of small, gradual steps with the goal of autonomy (Arnett, 2000; Iglehart & Becerra, 2002); however, youth emancipating or transitioning from foster care may enter young adulthood in one big step.

Studies that have measured current foster youth who are transitioning to young adulthood suggest that foster youth are concerned about this transition. Cunningham and Diversi (2012) interviewed a small sample of youth who were transitioning to independence and found youth were concerned about facing financial and housing instability, a loss of social support, and pressure to be independent. Shin (2009) conducted 152 interviews with randomly selected foster youth who were on the cusp of emancipation to assess if youth were properly trained for independence. Findings suggested that while the majority of youth had received independent living skills training, they experienced poor mental health and limited educational achievement which likely would impede the use of independent living skills post emancipation.

Other research has found that independent living programs may little impact on long-term outcomes. Courtney, Zinn, Koralek, and Bess (2011) assessed multi-site independent living programs designed to impact key outcomes for youth that included employment, educational attainment, relationship skills, and reduced delinquency and crime rates. Using random assignment 229 youths were assigned to receive independent living programs or to the control group. The study found no impact on any key outcomes between youth who were receiving independent living programs and those in the control group. Similarly, a secondary data analysis of this study found that there was no difference in social support trajectory between youth who received independent living services and those in the control group (Greeson, Garcia, Kim, Thompson, & Courtney, 2015). Jones (2014) conducted interviews with 106 youth 6 months after discharge from foster care and assessed their perspectives of independent living services. Findings indicated that youth felt independent living services did not meet their needs after exit from care and that services needed to be more realistic.

Sexual Minority Youth

Youth who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ) are at an increased risk to experience social stigma and discrimination and are at an increased risk for substance use and misuse when compared to heterosexual peers (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2017). Marshal et al. (2008) conducted a meta-analysis, using National Institutes of Health meta-analysis software, on 18 published studies that assessed the relationship between LGB status and adolescent substance use. They found that LGB youth had an odds of substance use that were on average 190% higher than substance use for heterosexual youth. Child welfare experiences may impact substance use for LGBTQ youth. Recent research suggests differences in child welfare experiences for sexual minority youth. LGBTQ youth in foster care, when compared to their heterosexual peers, experience a higher number of child welfare placements and longer lengths of stay (Mallon, Aledort, & Ferrera, 2002; Wilson, Cooper, Kastanis, & Nezhad, 2014). The social stigma and discrimination combined with differences in child welfare experiences suggests that LGBTQ youth in foster care have an increased vulnerability for substance use and misuse. Services and programs for youth in-care should be designed to address substance use and misuse prevention, housing stability, and independent living preparation needs unique to the youth, and should address needs of sexual minority youth.

Current Study

To first understand what services or programs can be useful for substance use awareness or prevention for current foster youth, prevalence rates of substance usage must first be understood. This study adds to the literature on the prevalence of substance use and experiences with housing and independent living among current and former foster youth. The following three research questions were addressed: (1) what is the prevalence of alcohol and illicit drug use among current and former foster youth and does prevalence vary by demographics (gender expression, race/ethnicity, and sexual minority status); (2) what is the relationship between prior or current housing instability and substance use?; and (3) what is the relationship between independent living preparation and substance use?

Methodology

This study used a cross-sectional design that included paper and web-based self-administered surveys. Data were collected from Summer 2014 to January 2015. The study occurred in a mid-Atlantic state, where youth are able to remain in care through the age of 21. Two samples of participants were recruited: youth currently in an out-of-home placement and former foster youth. Youth in-care were aged 14–21 from rural counties and the former foster youth largely had been in child welfare care from the state’s largest urban jurisdiction. University institutional review board approval as well as approval from the state child welfare department were received for this study. A previous study utilizing the same sample explored well-being for youth in-care and former foster youth and has been recently published, (see Greeno, Fedina, Lee, Farrell, & Harburger, 2018—deidentified for revision).

Recruitment and Procedures

The total study sample was comprised of 291 youth [87% (254) were former foster youth and 13% (37) were youth currently in-care]. The study was approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. Recruitment procedures were specific to each subsample, described below. Each study participant received a $25 gift card for participating in the survey. All participants completed the same set of surveys in approximately 30–40 min.

Youth In-Care

Research staff collaborated with child welfare caseworkers to identify all current foster youth age 14–21 in out-of-home placements, in five rural jurisdictions in a mid-Atlantic state. These five rural jurisdictions were chosen to participate as they were involved with an evaluation as part of the grant award. Youth in-care who were over the age of 18 were given an explanation of the study by research staff or their child welfare worker and were able to consent to participate in the study. Youth who were between the ages of 14–18 were explained the study by research staff and a child welfare worker and were able to assent to participate in the study; consent was obtained from their legal guardian (either the child welfare worker or caregiver). To prevent youth from feeling coerced to participate in the study, all child welfare workers were advised of study participant rights and the voluntary nature of the study. Of the 46 youth who were eligible to participate in the study, 37 youth consented to participate, yielding a participation rate of 80% for youth currently in-care.

After consenting to participate in the study, a researcher met with the youth at their residence or a place of convenience for the youth. Youth were given the survey packet (paper and pencil format) and were allowed privacy to complete the surveys. Research staff were available to answer questions. All measures were administered by a research staff member.

Former Foster Youth

Former foster youth, who were over the age of 18 and had been in an out-of-home placement, were eligible to participate in the study. Efforts to locate former foster youth in the same five rural jurisdictions as the current foster youth were unsuccessful. As an alternative, the principal investigator of the study collaborated with a foster care alumni association based in an urban jurisdiction to assist with recruiting eligible young adults to complete the survey online. This non-profit works with vulnerable, at-risk former foster youth who are seeking services related to housing, education, employment, as well as parenting needs. Survey questions were added to ensure that only youth who had received services in the study state, when they were between the ages of 14–21, were included in the study. The principal investigator verified that each former foster youth participant was both eligible and appropriate for the study. A link to the online survey was posted on the organization’s social media pages and a number of the agency’s clients came into the office to complete the survey. The link was available for a 48-h period and procedures were put in place to assure that each former foster youth took the survey only one time. These efforts resulted in a total sample of 254 surveys completed by young adults with foster care histories.

Measures

Demographics

All sample participants were given a brief demographic questionnaire that assessed for age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender expression. Due to low response frequency in some categories, race/ethnicity was collapsed into two options for analyses: non-White (comprised of African American, Hispanic, and More than one race categories) and White. Similarly, for sexual orientation and gender expression, analyses combined LGBTQ youth due to few cases in bisexual, transgender, and questioning categories. Housing instability was assessed for former foster youth by asking whether the young adult had ever spent at least one night in a shelter or stayed with friends or relatives (because there was no other place to stay) in the year after they left care.

AUDIT-C

The AUDIT-C (Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001) is a brief 3-item screen that can help identify hazardous drinking and the potential for alcohol use disorders. The 3-questions assess: (1) overall drinking frequency in the past month, (2) typical quantity of drinks consumed (in the past month), and (3) frequency of drinking five or more drinks at a time (in the past month). It is a modified version of the 10-item AUDIT measure (Babor et al., 2001). Each item is scored on a scale of 0–4 points for a maximum of 12 points. For males, a score of 4 or higher and for females a score of 3 or more suggests hazardous drinking or active alcohol use disorders. The AUDIT-C can also classify binge drinkers based on any positive response to the item: how often do you have six or more drinks on one occasion. The reliability of the AUDIT-C for youth currently in-care was low, with a Cronbach alpha of 0.505. The reliability of the AUDIT-C for former foster youth was adequate with Cronbach alpha of 0.80.

DAST-10

The DAST (Skinner, 1982) is a 10-item brief screening tool with a yes or no response option for each item; scores range from 0 to 10. The measure assesses drug use, not including alcohol or tobacco use in the past 12-months. A sum score of the DAST was used to assess for differences between the subpopulatoins. Each DAST score corresponds with a degree of problems related to drug use: no problems reported (0), low level (1–2), moderate level (3–5), substantial level (6–8), or severe level of problems (9–10) related to drug abuse. For each score, suggested actions for treatment are recommended. The reliability of the DAST was adequate for both groups; current youth in-care had a Cronbach alpha of 0.77 and former youth in-care had a Cronbach alpha of 0.80.

Preparation for Independence

To assess for preparation for independence a brief survey was designed for this study. Research staff collaborated with child welfare staff to develop a 7-item survey that briefly assessed whether the youth perceived they had received any preparation in seven key domains of independence: housing, social skills, education, mental health, work skills, managing your money, and living alone. Current youth in-care were asked, has anyone talked to you about the following areas as you transition to adulthood? Former foster youth were asked, while you were in care did anyone talk to you about or prepare you for the following. Response options for both groups were a yes/no. A summative scale was created with a point for each area that was indicated as a ‘yes’ for reported independence preparation for a range of 0–7 points, with higher scores suggesting more areas of preparation. The reliability for preparation scales was adequate with a Cronbach alpha of 0.70 for youth in-care and 0.87 for former foster youth.

Data Analyses

Data analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 22.0. Descriptive and bivariate analyses were used to assess demographic and substance use findings. Cohen’s d was used to assess effect sizes for bivariate analyses. Multiple regression analyses were conducted to assess the relationship between independence preparation and substance consumption. Because of the differences in ages and differences in recruitment strategies for the two subgroups, differences between the subgroups are not presented.

Results

Table 1 details demographics and bivariate findings for youth currently in-care and former foster care samples. Youth in-care had an average age of 17 (SD = 2, range 14–20) and former foster youth had an average age of 22 (SD = 1.5, range 20–28).The overall study population was largely male with the majority (99%, n = 252) of former foster youth identifying as male and 58% of youth-in care identifying as male. Regarding LGBTQ status, 61% (n = 154) of former foster youth and 73% (n = 24) of youth currently in-care identified as non-LGBTQ. About half of both samples identified as White. 97% of former foster youth (n = 247) indicated they had children.

Housing instability in the year since leaving care was endorsed by every former foster youth; 100% had stayed with a friend or relative after leaving care because they had no other place to stay and 99% (n = 252) had stayed in a shelter since leaving care. For youth currently in-care, 24% (n = 9) indicated they had stayed in shelters prior to coming into care.

Prevalence of Substance Use

Alcohol Use

Table 2 details findings for the AUDIT-C and DAST measures. Of the 37 youth in-care, 23 (62%) indicated they were not consuming any alcohol. Of the 14 youth (38%) who had consumed alcohol in either the past month, six identified as male and eight identified as female. The average AUDIT-C score for a female was 4.1 (SD = 3); and the average for males was 4.5 (SD = 1), indicating that on average, among youth in-care who were drinking, regardless of gender, they scored in the AUDIT-C alcohol hazardous drinking range. There were no significant differences between the genders and level of alcohol consumption [χ2 (df = 1) = 0.529] for youth currently in-care. Overall, 22% (n = 8) of the youth in-care who were consuming alcohol were identified as hazardous drinkers on the AUDIT-C. Of the 14 youth who were consuming alcohol, 43% (n = 6) drank between one and two drinks when consuming alcohol and 64% (n = 9) were identified as binge drinkers.

For former foster youth, 98% (n = 249) indicated they drank two to four times a month and 96% (n = 245) drank between five and six drinks when consuming alcohol, indicating binge drinking patterns. Hazardous drinking was indicated for 99% (n = 252) of all former foster youth.

Drug Use

Youth currently in-care averaged a score of 1.8 (SD = 2) on the DAST, indicating low level problems with illicit substances. Former foster youth scored an average of 8 (SD = 1) on the DAST, suggesting substantial problems with illicit substances.

Table 2 details findings of the DAST problem classifications. For youth in-care, 32% (n = 12) did not use illicit substances, 41% (n = 15) had low level problems, 16% (n = 6) had moderate problems and 11% (n = 4) had substantial or severe problems. Conversely, for former foster youth, 59% (n = 150) scored in the substantial problems range and 39% (n = 98) scored in the severe problems range on the DAST.

Prevalence of Substance Use and Demographics

A series of independent t tests were used to assess for differences in substance consumption (measured by the AUDIT-C and DAST) based on race/ethnicity, gender, and LGBTQ status for the two subgroups. For both youth in-care (AUDIT-C, t = 0.156, ns; DAST, t = 0.769, ns) and former foster youth (AUDIT-C, t = 0.176, ns; DAST, t = 0.345, ns), there were not any differences in substance consumption for race/ethnicity. For youth currently in-care, there were not any differences in gender (AUDIT-C, t = − 0.462, ns; DAST, t = − 0.746, ns) or LGBTQ status (AUDIT-C, t = 0.364, ns; DAST, t = − 1.405, ns) for substance consumption.

Differences were found for LGBTQ status for former foster youth; non-LGBTQ former foster youth had a mean score of 7 (SD = 0.6) and LGBTQ former foster youth scored a 6 (SD = 0.3) on the AUDIT-C (t [252] = 15.23, p < .0001); Cohen’s d = 0.4 (medium effect size). Significant drug use differences were also found. LGBTQ former foster youth scored on average a 9 (SD = 0.5) and non-LGBTQ youth scored a 7 (SD = 0.1) on the DAST (t [247] = − 45.460, p < .0001), Cohen’s d = 0.36 (small to medium effect size). LGBTQ former foster youth had higher levels of drug use and non-LGBTQ former foster youth had higher levels of alcohol use. The t test differences and medium effect sizes suggest different alcohol and illicit drug consumption between both LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ current and former foster youth.

LGBTQ Status and Substance Use

Multiple regression analyses were used to assess the impact of LGBTQ status on alcohol and illicit drug consumption. For alcohol use, LBGTQ status was associated with use. Current foster youth in-care and former foster youth who self-identified as LGBTQ were less likely to engage in hazardous alcohol consumption, with an approximate decrease in the AUDIT-C score of 1-point, [R2 = .031, F(1, 287) = 9.135, p = .003; β = − 0.714, p = .003]. There was also a difference in illicit drug consumption. Current foster youth in-care and former foster youth who identified as LGBTQ were more likely to engage in illicit drug consumption, with an approximate 2-point increase in the DAST total score [R2 = .212, F(1, 282) = 75.591, p < .0001; β = 2.109, p ≤ .0001].

Prevalence of Preparation for Independence

Over 90% of youth currently in-care indicated that someone had talked to them about preparing for independence in terms of education and work skills. However, only 78% of youth had been talked to about housing and only 57% had been talked to about living alone. Table 3 details complete results. For former foster youth, over 90% indicated they had been talked to about preparation in the areas of education, mental health, and managing your money. However, only 42% of former foster youth indicated they had been prepared for housing, social skills, work skills, and living alone.

A total score was also calculated for the preparation variables. On average, youth in-care reporting being talked to about a total of 5.8 (SD = 1.5, range 2–7) of the 7 independence areas. Over half of youth in-care (51%) had been talked to about all 7 independence preparation areas. On average, former foster youth reported being talked to about a total of 4.6 independence areas (SD = 2, range 0–7). However, for former foster youth, 57.5% reported being talked to in 3 areas while 41% reported being talked to about all 7 areas. See Table 3 for complete details.

Association Between Housing Variables and Substance Use

The relationship between shelter use and substance consumption was also examined. For youth in-care, findings were non-significant; a history of shelter use had no impact on either alcohol (t = 0.913, ns) or illicit drug consumption (t = − 0.460, ns). Because all former foster youth reported housing instability, lack of variation prevented subsequent analysis in the relationship to substance consumption.

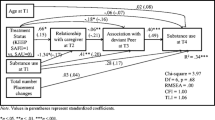

Association Between Preparation Variables and Substance Use

The relationship between total number of preparation areas (range of scores 0–7) and substance consumption, as measured by the AUDIT-C and DAST was examined using multiple regression. For current foster youth in-care, the total score on the independence preparation scale was not associated with findings on either the AUDIT-C [R2 = .03, F(1, 35) = 0.030, p = .862] and DAST [R2 = .12, F(1, 35) = 0.512, p = .479].

For former foster youth, both models were significant with greater preparation being associated with lower substance use. For the AUDIT-C [R2 = .72, F(1, 251) = 275.388, p < .0001; β = 0.21, p < .0001], for every additional area in total preparation for independence, former foster youth scored 0.21 points lower on the AUDIT-C. For the DAST, [R2 = .93, F(1, 247) = 1609.862, p < .0001; β = 0.50, p < .0001] for every additional area in total preparation for independence, former foster youth scored 0.5 points lower on the DAST.

Limitations

This study presents descriptive and prevalence statistics for substance consumption, housing instability, and youth self-perceived preparation for independent living. There are several limitations to the survey methodology that must be taken into consideration. The former foster youth in this sample were vulnerable young adults who were seeking assistance from a non-profit organization, and as such may not be representative of all former foster youth in this mid-Atlantic state, or general foster youth alumni. These were vulnerable, young males and findings for substance usage should be taken into consideration of this context. Additionally, a more meaningful study would include longitudinal analyses to assess substance usage, for both populations, over time. For both youth in-care and former foster youth, the type, number and duration of child welfare placement(s) they experienced were not collected. Experiences in out-of-home care including the stability of these placements as well as type of placement (i.e., foster home, group home) are known to be associated with risk factors for negative outcomes, including substance involvement and homelessness (for example, see Vaughn, Ollie, McMillen, Scott Jr, & Munson, 2007). Length of time in foster care may also impact the opportunities and experiences available to youth as well as their preparation for independence, particularly in a state that allows youth to remain in care through the age of 21. The measure of independence preparation was subjective and as such was open to interpretation. Future studies should consider a more precise measure for independent living preparation that would include independence preparation material youth may have been exposed to through one-on-one conversations and/or through formal classes. An additional limitation for the sample of former foster youth is that the majority of respondents were male who reported having at least one child. It is not known why more males answered the survey. The survey was open only for 48 h and it is possible that the availability of the survey spread by word of mouth and more males were in contact with each other. More female participants may have impacted findings, especially as they are more commonly primary caregivers of offspring.

Implications for Social Work Practice

This study documented an alarmingly high rate of substance consumption, both alcohol and illicit drug use, for former foster youth. Former foster youth consumed illicit substances and alcohol at a higher rate than non-child welfare college age young adults (a comparative sample based on age). National data indicates that 39% of young adults in college had used any illicit drug (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, Schulenberg, & Miech, 2016) compared to 98% of former foster youth in this study with indicated illicit substance use. Similarly, national estimates suggest that binge drinking was indicated in 38% of college age students compared to 33% of same age non-college age students (SAMSHA, 2014). Binge drinking was indicated in 96% of former foster youth in this study. However, the vulnerable nature of the former foster youth must be taken into consideration.

Results suggest that youth in-care have alcohol use rates similar to national samples but reported less illicit substance use. Nationally, any alcohol use for 12th graders was indicated for 37.4% of the population and binge drinking was indicated for 19% of the population (SAMSHA, 2014). 38% of youth in-care indicated they had consumed alcohol in the past month and 24% (n = 9) of youth in-care binge drank in the past month. Nationally, illicit substance use in the past year for 12th graders ranged from 35% for marijuana to 5% for vicodin (NIDA, 2014). Comparatively, more than one-fourth of this sample reported some degree of illicit substance use. Considering that some respondents were as young as 14 (age range of 14–20), youth in-care may benefit from early substance use prevention and intervention. The rural and urban backgrounds of the study participants should be taken into consideration. Previous research has suggested that adolescent substance use for non-child welfare populations in rural communities is equal to or greater than substance use of adolescents in urban populations (National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, 2000; Shears, Edwards, & Stanley, 2006).

This study also documented an alarming rate of housing instability for former foster youth. This finding speaks to the need of preparation of youth prior to leaving child welfare and the supports that foster care alumni need to obtain affordable and safe housing. Similar to the housing instability finding, an additional concerning finding was the perceived preparation for independence variables for former foster youth. Over 90% of the former foster youth indicated they had been talked to in the areas of education, mental health, and managing money, but only about 40% indicated they had been prepared in the areas of housing, social skills, work skills, and living alone. For former foster youth, the comprehensiveness of a youth’s preparation was related to substance usage. For both alcohol and illicit drug use, those former foster youth who reported more preparation for independence had lower scores for substance consumption. While former foster youth indicated they received some type of preparation for independence, the youth still struggled with housing and substance use, suggesting the need for focused preparation in these areas. In addition, independence preparation programs should include a specific element of substance use prevention and awareness of substance use disorders. In light of findings from this study and other reviews of substance use by youth in-care (see Braciszewski & Stout, 2012) the need for targeted interventions to prevent substance abuse is clear. Particularly in states where the youth are able to stay through the age of 21, there are opportunities to provide targeted services. Life skills classes offer a means of one-on-one interaction with youth and topics such as substance usage, housing preparation, and preparation to live independently should be specifically targeted.

A fairly high number of youth in-care (27%) and former foster youth (39%) identified as LGBTQ. For former foster, non-LGBTQ young adults drank more and used less illicit substances than LGBTQ former foster youth; findings that are somewhat different than what has been reported in recent research. Two recent studies found that youth who identified as LGBT consumed more alcohol than their heterosexual counterparts (see Coulter, Marzell, Saltz, Stall, & Mair, 2016; Roxburgh, Lea, de Wit, & Degenhardt, 2016). Research regarding sexual orientation and identity and illicit substance use is mixed; with some studies suggesting LGBT young adults do not have differing illicit substance use than non-LGBTQ (see Ford & Jasinski, 2006) and other studies suggesting a degree of greater illicit substance consumption among LGBT youth (see Brewster & Tillman, 2012). Findings suggest the need for an individualized approach to treatment planning for all youths in foster care and ongoing support after emancipation.

Conclusion

Despite the study’s limitations, our findings contribute to the knowledge of substance consumption for current and former foster youth as well as the impact of independence preparation. Findings suggest the need for interventions designed to specifically address substance usage and treatment both while youth are in care and after they exit to independence. This study found promising results for independence preparation with findings suggesting former foster youth were impacted by independence preparation. Additional research is needed to determine how to best support current and former foster youth to address substance use and to prepare for exit to independence.

References

Aarons, G. A., Monn, A. R., Hazen, A. L., Connelly, C. D., Leslie, L. K., Landsverk, J. A., et al. (2008). Substance involvement among youths in child welfare: The role of common and unique risk factors. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 78, 340–349.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480.

Babor, T. F., Higgins-Biddle, J. C., Saunders, J. B., & Monteiro, M. G. (2001). The alcohol use disorders identification test: Guidelines for use in primary care (2nd ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization.

Bender, K., Yang, J., Ferguson, K., & Thompson, S. (2015). Experiences and needs of homeless youth with a history of foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 55, 222–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.06.007.

Berzin, S. C., Rhodes, A. M., & Curtis, M. A. (2011). Housing experiences of former foster youth: How do they fare in comparison to other youth? Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 2119–2126.

Braciszewski, J. M., & Stout, R. L. (2012). Substance use among current and former foster youth: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 34, 2337–2344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.08.011.

Brewster, K. L., & Tillman, K. H. (2012). Sexual orientation and substance use among adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 1168–1176.

Casanueva, C., Stambaugh, L., Urato, M., Fraser, J. G., & Williams, J. (2014). Illicit drug use form adolescence to young adulthood among child welfare-involved youths. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 23, 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/1067828X.2012.735514.

Chen, X., Thrane, L., Whitbeck, L. B., & Johnson, K. (2006). Mental disorders, comorbidity, and post-runaway arrests among homeless and runaway adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16, 379–402.

Coulter, R. W. S., Marzell, M., Saltz, R., Stall, R., & Mair, C. (2016). Sexual-orientation differences in drinking patterns and use of drinking contexts among college students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 160, 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.01.006.

Courtney, M., Terao, S., & Bost, N. (2004). Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Conditions of the youth preparing to leave state care. Chicago: Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago.

Courtney, M., Zinn, A., Koralek, R., & Bess, R. (2011). Evaluation of the independent living-employment services program, Kern County, California: Final report. OPRE report#2011-13. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Cunningham, M. J., & Diversi, M. (2012). Aging out: Youths’ perspectives on foster care and the transition to independence. Qualitative Social Work, 12, 587–602.

Ford, J. A., & Jasinski, J. L. (2006). Sexual orientation and substance use among college students. Addictive Behaviors, 31, 404–413.

Greeno, E. J., Fedina, L., Lee, B. R., Farrell, J., & Harburger, D. (2018). Psychological well-being, risk, and resilience of youth in out-of-home care and former foster youth. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-018-0204-1.

Greeson, J. K. P., Garcia, A. R., Kim, M., Thompson, A. E., & Courtney, M. E. (2015). Development and maintenance of social support among aged out foster youth who received independent living services: Results from the multi-site evaluation of foster youth programs. Children and Youth Services Review, 53, 1–19.

Hudson, A. L., & Nandy, K. (2012). Comparisons of substance abuse, high-risk sexual behavior and depressive symptoms among homeless youth with and without a history of foster care placement. Contemporary Nurse, 42, 178–186.

Iglehart, A., & Becerra, R. (2002). Hispanic and African American youth: Life after foster care emancipation. Social Work with Multicultural Youth, 11(1), 79–107.

Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., Schulenberg, J. E., & Miech, R. A. (2016). Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2015. Volume 2: College students and adult ages 19–55. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan.

Jones, L. P. (2014). Former foster youths perspectives on independent living preparation six months after discharge. Child Welfare, 93, 99–126.

Mallon, G., Aledort, N., & Ferrera, M. (2002). There’s no place like home: Achieving safety, permanency, and well-being for lesbian and gay adolescents in out-of-home care settings. Child Welfare, 81, 407–439.

Marshal, M. P., Friedman, M. S., Stall, R., King, K. M., Miles, J., Gold, M. A., et al. (2008). Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: A meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction, 103, 546–556.

Narendorf, S. C., & McMillen, J. C. (2010). Substance use and substance use disorders as foster youth transition to adulthood. Children and Youth Series Review, 32, 113–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.07.021.

National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. (2000). No place to hide: Substance abuse in mid-sized cities and rural America. New York: Columbia University.

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2014). DrugFacts: High school and youth trends. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/high-school-youth-trends.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2017). Substance use and SUDS in LGBT populations. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/substance-use-suds-in-lgbt-populations#references.

National Institutes of Health. (2008). Alcohol research: A lifespan perspective. Retrieved from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/AA74/AA74.pdf.

Park, J. M., Metraux, S., Broadbar, G., & Culhane, D. P. (2004). Child welfare involvement among children in homeless families. Child Welfare, 83, 423–436.

Pilowsky, D. J., & Wu, L. (2006). Psychiatric symptoms and substance use disorders in a nationally representative sample of American adolescents involved with foster care. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38, 351–358.

Roxburgh, A., Lea, T., de Wit, J., & Degenhardt, L. (2016). Sexual identity and prevalence of alcohol and other drug use among Australians in the general population. International Journal of Drug Policy, 28, 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.11.005.

Shears, J., Edwards, R. W., & Stanley, L. R. (2006). School bonding and substance use in rural communities. Social Work Research, 30, 6–18.

Shin, S. H. (2009). Improving social work practice with foster adolescents: Examining readiness for independence. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 3, 354–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548730903347820.

Skinner, H. A. (1982). The drug abuse screening test. Addictive Behaviors, 7, 363–371.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). The NSDUH report: Underage binge alcohol use varies within and across states. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral health Statistics and Quality.

Thompson, S. J. (2004). Risk/protective factors associated with substance use among runaway/homeless youth utilizing emergency shelter services nationwide. Substance Abuse, 25, 13–26.

Vaughn, M. G., Ollie, M. T., McMillen, J. C., Scott, L. Jr., & Munson, M. (2007). Substance use and abuse among older youth in foster care. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 1929–1935.

Wall, A. E., & Kohl, P. L. (2007). Substance use in maltreated youth: Findings from the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being. Child Maltreatment, 12, 137–149.

Wilson, B., Cooper, K., Kastanis, A., & Nezhad, S. (2014). Sexual and gender minority youth in foster care: Assessing disproportionality and disparities in Los Angeles. Los Angeles: The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law.

Acknowledgements

Funded through Planning Grants to Develop a Model Intervention for Youth/Young Adults with Child Welfare Involvement At-Risk of Homelessness and U.S. Children's Bureau [HHS-2013-ACF-ACYF-CA-0636].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Greeno, E.J., Lee, B.R., Tuten, M. et al. Prevalence of Substance Use, Housing Instability, and Self-Perceived Preparation for Independence Among Current and Former Foster Youth. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 36, 409–418 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-018-0568-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-018-0568-y