Abstract

Data from a nationally representative probability-based online survey sample of US adults conducted in 2015 (n = 3949, response rate 55%) were used to assess self-reported gun storage practices among gun owners with children. The presence of firearms and children in the home, along with other household and individual level characteristics, was ascertained from all respondents. Questions pertaining to household firearms (how guns are stored, number, type, etc.) were asked only of those respondents who reported that they personally owned a gun. We found that approximately one in three US households contains at least one firearm, regardless of whether children lived in the home (0.34 [0.29–0.39]) or not (0.35 [0.32–0.38]). Among gun-owning households with children, approximately two in ten gun owners store at least one gun in the least safe manner, i.e., loaded and unlocked (0.21 [0.17–0.26]); three in ten store all guns in the safest manner, i.e., unloaded and locked (0.29, [0.24–0.34]; and the remaining half (0.50 [0.45–0.55]) store firearms in some other way. Although firearm storage practices do not appear to vary across some demographic characteristics, including age, sex, and race, gun owners are more likely to store at least one gun loaded and unlocked if they are female (0.31 [0.23–0.41]) vs. male (0.17 [0.13–0.22]); own at least one handgun (0.27 [0.22–0.32] vs. no handguns (0.05 [0.02–0.15]); or own firearms for protection (0.29 [0.24–0.35]) vs. do not own for protection (0.03 [0.01–0.08]). Approximately 7% of US children (4.6 million) live in homes in which at least one firearm is stored loaded and unlocked, an estimate that is more than twice as high as estimates reported in 2002, the last time a nationally representative survey assessed this outcome. To the extent that the high prevalence of children exposed to unsafe storage that we observe reflects a secular change in public opinion towards the belief that having a gun in the home makes the home safer, rather than less safe, interventions that aim to make homes safer for children should address this misconception. Guidance alone, such as that offered by the American Academy of Pediatrics, has fallen short. Our findings underscore the need for more active and creative efforts to reduce children’s exposure to unsafely stored firearms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2015, 1468 US children under the age of 18 died as the result of a gunshot wound and almost 7000 were non-fatally injured with a gun [1]. Of those children who died by firearm, 40% died either by suicide or as the result of an unintentional firearm injury, most often inflicted by themselves or another child [2]. In contrast to firearm deaths among adults, most firearm deaths of children, especially younger children, occur in their own homes [3]. For suicides and unintentional deaths, the gun used in the death almost always comes from the child’s home [4].

A large body of evidence has shown that the presence of guns in a child’s home substantially increases the risk of suicide and unintentional firearm death [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18], though recent data suggest that few gun owners appreciate this risk [19]. Moreover, the risk of unintentional and self-inflicted firearm injury is lower in homes that store firearms unloaded (compared with loaded) and locked (compared with unlocked) [20]. In keeping with this evidence, guidelines intended to reduce firearm injury to children, first issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) in 1992 [21], assert that whereas the safest home for a child is one without firearms, risk can be reduced substantially, although not eliminated, by storing all household firearms locked, unloaded, and separate from ammunition [20].

Only three nationally representative studies, and none since the early 2000s, have estimated the proportion of children living in homes where firearms are stored in the least safe manner (i.e., unlocked and loaded). Two of these studies used survey data from 1994 (the National Health Interview Survey and the Injury Control and Risk Survey) [22, 23]; the other used data from 2002 (the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey) [24]. All three studies found that approximately 10% of gun-owning households with children contained at least one loaded and unlocked firearm.

Although household gun ownership rates in the USA have remained relatively stable over the past two decades [25], patterns of and reasons for gun ownership have shifted since the early 2000s, possibly affecting firearm storage practices. Over this period, millions of guns, the large majority of which are handguns, have been added to the US gun stock [26]. Handguns are more often owned for personal or household protection, compared to long guns [26], and are far more likely to be stored loaded and unlocked [27, 28]. Consistent with the shift in the gun stock, public opinion regarding the risks and benefits of having a firearm in the home also appear to have changed. According to polling conducted by Gallup, in 2000, approximately 35% of US adults believed that “a gun in the home makes it a safer place to be,” whereas by 2014, 63% did [29].

The current study provides the first contemporary estimate in over 15 years of the number of US children who live in households with guns and, within these households, how firearms are stored.

Methods

Design and Sampling

Data for this analysis came from a nationally representative Web-based survey (The National Firearms Survey) designed by the investigators (D.A. and M.M.) to describe firearm ownership, storage, and use in the USA. The survey was conducted by the firm Growth for Knowledge (GfK) in April 2015. Respondents were drawn from GfK’s KnowledgePanel, an online panel comprised of approximately 55,000 US adults sampled on an ongoing basis. Invitations to participate were sent by e-mail; one reminder e-mail was sent to non-responders 3 days later. All panel members, except those serving in the US Armed Forces at the time of the survey, were eligible to participate. To ensure reliable estimates, firearm owners and veterans were oversampled. Participants did not receive any specific incentive to complete the survey, although GfK has a point-based program through which participants accrue points for completing surveys and can redeem them later for cash, merchandise, or participation in sweepstakes. Additional details about the survey design and participants are available elsewhere [30].

Of the 7318 invited panel members who received the survey, 4165 began the survey and 3949 completed it (excluding 48 active-duty military personnel who began the survey but were ineligible to complete it). This yielded a survey completion proportion of 55% based on the formula recommended for calculating response proportions for Web panels [31]. Respondents were more likely than non-respondents to be younger, female, unmarried, less educated, and living in metropolitan areas. Respondents were about as likely as non-respondents to live in a firearm-owning house, but were more likely to personally own a firearm.

The study was approved by the Northeastern University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Gun Ownership Status

The preamble to the survey read: “The next questions are about working firearms. Throughout this survey, we use the word gun to refer to any firearm, including pistols, revolvers, shotguns, and rifles, but not including air guns, bb guns, starter pistols, or paintball guns. By ‘working guns’, we mean guns that are in working order—that is capable of being fired.” Immediately, following this preamble, respondents were asked “Do you or does anyone else you live with currently own any type of gun?” Those who responded affirmatively were asked a second question: “Do you personally own a gun?”

Only respondents who reported personally owning firearms were asked specific questions about household firearms, including the number and types of guns in the home, how guns were stored, and reasons for owning firearms. Specifically, respondents were asked: “Do you personally own any of the following types of guns? (handguns, long guns, other guns),” and then, for each firearm type owned by the respondent, “How many (handguns, long guns, other guns) do you own?” Thus, for each respondent, the total number of handguns, long guns, and “other” guns they owned could be tabulated.

Gun Storage

For each type of firearm (handgun, long gun, other), gun owners were asked to specify the number of guns they stored loaded and unlocked, loaded and locked, unloaded and unlocked, and unloaded and locked. Based on responses to these questions, for primary analyses, gun owners were sorted into one of three hierarchical, mutually exclusive, and collectively exhaustive categories: (1) those who stored at least one gun loaded and unlocked (the least safe storage method), (2) those who stored no guns loaded and unlocked but at least one gun loaded and locked, or unloaded and unlocked (the intermediate-risk category), and (3) those who stored all guns unloaded and locked (the safest storage method). The two types of storage in the intermediate-risk category were combined because the relative risk of a loaded and locked gun, compared with an unloaded and unlocked gun, was determined to be too context-specific to generalize about which is safer. Respondents (n = 13) who refused to answer any questions about how their guns were stored were excluded.

Demographic, Socio-Economic, and Firearm-Related Variables

Additional variables included in our analyses were age (18–29, 30–44, 45–59, ≥ 60), respondent gender, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, other), education (< high school, high school degree, some college, ≥ Bachelor’s degree), household income (< $25,000, $25,000–$59,999, $60,000–$99,999, ≥ $100,000), US region of residence (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), and rurality of residence (urban, suburban, rural). Whether or not the respondent had children living with them is reported as a mutually exclusive hierarchical variable: any child under 6 years old (yes/no), any child 6–12 years old but no child under 6 (yes/no), and any child 13–17, but no child under 13 (yes/no). Respondent political ideology was reported as liberal, moderate, or conservative. The type of guns owned by respondents was categorized as own at least one handgun vs. own no handguns. Respondents were asked for each type of gun they owned, to indicate their main reasons for ownership (protection against strangers, protection against people they knew, protection against animals, hunting, other sporting use, or for a collection). For this analysis, we include a binary variable: owns any type of firearm for protection against people vs. all other reasons.

Analysis

Analyses used survey weights provided by GfK that combined pre-sample and study-specific post-stratification weights accounting for oversampling and nonresponse, to produce nationally representative estimates with 95% confidence intervals, following the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines for reporting [32]. All bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted with Stata Version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) using the SVY suite of commands.

We estimated the prevalence of children living in homes where guns are stored loaded and unlocked by multiplying the percentage of all households with children (obtained from 2015 Census data) by our survey-derived estimates of (a) the distribution of children in homes with vs. without firearms and (b) storage practices in homes with children and firearms.

Results

We find that approximately one in three US households contains at least one gun, whether the household includes children under the age of 18 (0.34 [0.29–0.39]) or not (0.35 [0.32–0.38]) (not shown). Among households with children, approximately two in ten store at least one gun loaded and unlocked (0.21, 95% CI 0.17–0.26), half store no guns loaded and unlocked, but have at least one gun either loaded and locked, or unloaded and unlocked (0.50, 95% CI 0.45–0.55), and three in ten store all guns unloaded and locked (0.29, 95% CI 0.24–0.34).

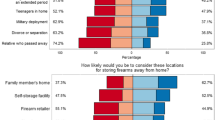

Gun storage practices do not vary significantly across most demographic characteristics of gun owners (Table 1), except gender: female gun owners in homes with children are more likely than are male gun owners in homes with children to store at least one gun loaded and unlocked (0.31 [0.23–0.41] vs. 0.17 [0.13–0.22]). Gun storage practices in homes with children also vary by US region, and the age of the youngest child in the household, although these results did not reach statistical significance. Those with older children only were more likely to store at least one gun loaded and unlocked than those with younger children (any child under 6, 0.17 [0.12–0.23]; no children under 6 and at least one child under 13, 0.22 [0.16–0.31]; no child under 13, 0.27 [0.19–0.37]). Households in which any gun is owned for protection are significantly more likely to contain a loaded and unlocked gun than are homes in which no guns are owned for protection (0.29 [0.24–0.35] vs. 0.03 [0.01–0.08]), as are households with at least one handgun, compared to those with no handguns (0.27 [0.22–0.32] vs. 0.05 [0.02–0.15].

A multiple logistic regression analysis (any gun loaded and unlocked vs. no gun loaded and unlocked) yielded consistent results. In a model adjusting for all of the respondent characteristics in Table 1, the adjusted odds for storing at least one household firearm loaded and unlocked was almost seven times higher for homes in which guns were owned for protection, compared with homes where guns were present but none were owned for protection (OR 6.94 [2.35–20.52]), more than four times higher in homes with handguns, compared to homes where all guns were long guns or other guns (OR 4.55 [1.44–14.39]), and almost twice as high for homes in which females owned firearms, compared to homes in which males owned firearms (OR 1.89 [1.04–3.43], Table 3 in Appendix).

Extrapolating from the reports of gun owners (i.e., that 21% of gun-owning households with children contain at least one gun that is both loaded and unlocked), we estimate that 7% of US households with children contain a loaded and unlocked gun (Table 2). Given that there were approximately 125 million US households in that year [33], 30% of which (37.5 million) included children under the age of 18, we estimate that about 13 million households with children (34%) contain at least one gun, and in approximately 2.7 million (21%) of these homes a gun is stored loaded and unlocked. Households with loaded and unlocked guns in our survey contained an average of 1.7 children, yielding an estimate of 4.6 million children (range 3.9–5.9 million) living in a household with a loaded and unlocked gun in 2015.

Discussion

Overall Firearm Storage Practices/Exposure

Consistent with prior national surveys, we find that approximately one-third of US households contain at least one gun, whether children live in the home or not [22, 26, 34]. Among gun-owning households, our finding that storage practices tend to be safer when children live in the home [23, 24, 27, 28, 34, 35], especially young children [22, 36], is also consistent with earlier work. By contrast, we find that nearly twice as many children live in homes where guns are stored loaded and unlocked, compared to the last nationally representative survey to assess this outcome (the 2002 BRFSS) [24]. For example, we find that approximately 21% of homes with children and guns store at least one gun loaded and unlocked, whereas the 2002 BRFSS estimates that approximately 8% of such homes had loaded and unlocked household firearms. Increases in the proportion of homes with children where firearms are stored loaded and unlocked, compounded by the growth of the US population of children since 2002, suggest that the number of children who live in homes with at least one loaded and unlocked firearm may have increased substantially over the past 15 years, from approximately 1.6 million to 4.6 million.

Three non-mutually exclusive reasons may contribute to the striking increase in the estimated number of children living in homes with guns stored unsafely: (1) growth in the US population; (2) a shift in the primary reasons people with and without children own guns, away from hunting and towards personal and home protection; and (3) methodological differences in the way that we assessed storage practices, compared to the approach taken in the BRFSS and other national studies. The first two reasons help explain a credible increase in exposure to unlocked, loaded firearms in general; the third suggests that some of the measured difference may be an artifact of systematic undercounting in prior reports due to the decision to elicit storage practice information from any household member, including non-gun-owning respondents, rather than as in our study, restricting questions to gun-owning respondents only.

Population Growth

A portion, but not all, of the nearly threefold increase in the number of children exposed to unsafely stored firearms we observe may be accounted for by US population growth since 2002. According to US Census figures, the US population grew by approximately 4.6 million households 2002–2015, approximately one third of which were gun-owning households. Assuming our survey-derived estimate of 1.7–1.8 children per gun-owning household has roughly obtained over the past 15 years, we estimate that an additional 600,000 children are living in a household with a loaded and unlocked gun due to population growth alone.

Shifting Patterns of and Reasons for Gun Ownership

Since the early 2000s, the composition of the US gun stock has shifted towards handguns (and away from long guns), and, consistent with the reasons people tend to own handguns, towards personal or household protection, and away from hunting or sporting uses alone [26]. Both these trends would be expected to lead to shifts in storage practices towards less safe storage, and in particular, towards household guns being stored loaded and unlocked [27, 28]. Consistent with the observed shift in the gun stock, public opinion regarding the risks and benefits of having a firearm in the home also appear to have changed: according to polling conducted by Gallup, for example, whereas in 2002, approximately 35% of US adults believed that “a gun in the home makes it a safer place to be,” by 2014, 63% did [29]. Because the 2002 BRFSS does not ascertain the types of guns people own, or reasons for gun ownership, quantitative assessment of the extent to which this secular shift contributes to the observed increase in children living in homes with guns is not possible.

Survey Effects

It is also possible that reports of household firearm storage from the BRFSS may have yielded underestimates of unsafe storage practices because of the well-established discrepancy between gun stock and gun storage estimates based on reports of subgroups more likely to personally own firearms, but no more likely to live in homes with guns (e.g., estimates based on reports by married men, compared with estimates based on reports of married women). This discrepancy is commonly referred to as the “reporting gap.” Historically, the reporting gap is substantial. For example, prior work has found that married men, compared with married women, are far more likely to report that there is any gun in their household and, conditional on reporting any gun, that there are more guns in their household [37]. Moreover, among people in two adult households with children, proxy reporters (i.e., non-gun-owning respondents who report living in homes with firearms) are more likely to report that guns are stored securely, compared with reports by gun owners themselves [38]. As a result of the reporting gap, most major recent surveys that have sought to estimate the stock of guns in the USA, or other characteristics of gun ownership (types and number of guns, etc.), have based their estimates on data provided by those who personally own guns only. Discrepancies due to the “reporting gap” might be compounded, to an indeterminate extent, because of reporting differences related to survey administration modes (e.g., random digit dial telephone survey vs. in-person vs. online), or to secular changes in proxy respondents’ knowledge about, and willingness to report, how firearms are actually stored in their homes. Although we know of no studies to date that have examined these issues quantitatively, it seems plausible that the shift towards owning household guns for protection may have increased the likelihood that non-gun-owning women in households with firearms are more knowledgeable about the presence of guns and how they are stored.

Factors Associated with Unsafe Firearm Storage

Our finding that female gun owners in households with children, compared with male gun owners in homes with children, are more likely to store at least one gun loaded and unlocked has not, as far as we can tell, been previously reported. Given the actuarial risk that loaded and unlocked firearms (as well as firearms in general) pose to children, additional research on this issue is warranted.

Our finding that storing at least one gun loaded and unlocked is more common in the South, and among those who own handguns and firearms for protection are consistent with work on firearm storage in general (i.e., in all households, or in sub-populations such as veterans) [27, 28, 35, 39, 40]; however, we are not aware of any prior work that presents data on firearm storage in households with children with respect to any of these characteristics.

As with findings from all self-report surveys, our study’s results should be interpreted in light of potential inaccuracies due to social desirability, recall, and other biases [41]. And while the magnitude of bias may vary for these possible sources of distortion, the direction of bias would likely be to underestimate, not overestimate, the prevalence of unsafe storage. In this regard, it is worth noting that online panel surveys, such as used here, have been shown to reduce social desirability bias and yield more accurate estimates of respondent characteristics than telephone surveys [42, 43]. In addition, prior research has validated survey responses to firearm questions on random-digit dial surveys, with false denials of gun ownership limited to approximately 10% [44, 45]. Another advantage of online panels is high completion rates for those who begin the survey [31]. Among gun owners in households with children, for example, only 2.8% (n = 13) declined to answer our questions about firearm storage. Finally, our survey completion rate (54.6%) is higher than rates for typical nonprobability, opt-in, online surveys (2–16%) [43], higher than those of previous national injury surveys that included questions about firearm ownership [46], and similar to those from other surveys conducted by GfK. Nevertheless, panel members who chose not to participate in our survey may have differed in important ways compared with panel members who chose to participate.

Despite these limitations, our study suggests that more than 1 in 15 US children (7%) live in a household in which at least one firearm is stored loaded and unlocked, and that the number of children who are exposed to unsafely stored guns appears to have grown substantially over the past 15 years. To the extent that the high prevalence of children exposed to unsafe storage that we observe reflects a secular change in public opinion towards the belief that having a gun in the home makes the home safer, rather than less safe, interventions that aim to make homes safer for children should address this misconception. Guidance alone, such as that offered by the American Academy of Pediatrics, has fallen short. Our findings underscore the need for more active and creative efforts to reduce children’s exposure to unsafely stored firearms.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Centers for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [online]. (2005) {cited 2018 Mar 15}. Available from: www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars.

Hemenway D, Solnick SJ. Children and unintentional firearm death. Inj Epidemiol. 2015;2(1):26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40621-015-0057-0.

Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D. Firearms and violent death in the United States. In: Webster DW, Vernick J, editors. Reducing Gun Violence in America: informing Policy with Evidence and Analysis. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

Grossman DC, Reay DT, Baker SA. Self-inflicted and unintentional firearm injuries among children and adolescents: the source of the firearm. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(8):875–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.153.8.875.

Miller M, Hemenway D. The relationship between firearms and suicide: a review of the literature. Aggress Violent Behav. 1999;4(1):59–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-1789(97)00057-8.

Brent DA. Firearms and suicide. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;932:225–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05808.x.

Anglemyer A, Horvath T, Rutherford G. The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(2):101-110. https://doi.org/10.7326/M13-1301.

Kellermann AL, Rivara FP, Somes G, Reay DT, Francisco J, Banton JG, et al. Suicide in the home in relation to gun ownership. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(7):467–72. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199208133270705.

Brent DA, Perper J, Moritz G, Baugher M, Allman C. Suicide in adolescents with no apparent psychopathology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32(3):494–500. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199305000-00002.

Brent DA, Perper JA, Allman CJ, Moritz GM, Wartella ME, Zelenak JP. The presence and accessibility of firearms in the homes of adolescent suicides. A case-control study. JAMA. 1991;266(21):2989–95. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1991.03470210057032.

Brent DA, Perper JA, Moritz G, Baugher M, Schweers J, Roth C. Firearms and adolescent suicide. A community case-control study. Am J Dis Child. 1993;147(10):1066–71. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1993.02160340052013.

Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Connor K, Eberly S, Cox C, Caine ED. Access to firearms and risk for suicide in middle-aged and older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10(4):407–16. https://doi.org/10.1097/00019442-200207000-00007.

Bailey JE, Kellermann AL, Somes GW, Banton JG, Rivara FP, Rushforth NP. Risk factors for violent death of women in the home. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(7):777–82. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.157.7.777.

Wiebe DJ. Homicide and suicide risks associated with firearms in the home: a national case-control study. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41(6):771–82. https://doi.org/10.1067/mem.2003.187.

Wintemute GJ, Parham CA, Beaumont JJ, Wright M, Drake C. Mortality among recent purchasers of handguns. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(21):1583–9. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199911183412106.

Dahlberg LL, Ikeda RM, Kresnow M-J. Guns in the home and risk of a violent death in the home: findings from a national study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(10):929–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwh309.

Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D. Firearm availability and unintentional firearm deaths, suicide, and homicide among 5–14 year olds. J Trauma. 2002;52(2):265–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005373-200202000-00011.

Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D, Vriniotis M. Firearm storage practices and rates of unintentional firearm deaths in the United States. Accid Anal Prev. 2005;37(4):661–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2005.02.003.

Conner A, Azrael D, Miller M. Public opinion about the relationship between firearm availability and suicide: results from a national survey. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(2):153–5. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-2348.

Grossman DC, Mueller BA, Riedy C, Dowd MD, Villaveces A, Prodzinski J, et al. Gun storage practices and risk of youth suicide and unintentional firearm injuries. JAMA. 2005;293(6):707–14. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.6.707.

Dowd MD, Sege R, Council on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention Executive Committee; American Academy of Pediatrics. Firearm-related injuries affecting the pediatric population. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):e1416–23. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-2481.

Schuster MA, Franke TM, Bastian AM, Sor S, Halfon N. Firearm storage patterns in US homes with children. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(4):588–94. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.90.4.588.

Stennies G, Ikeda R, Leadbetter S, Houston B, Sacks J. Firearm storage practices and children in the home, United States, 1994. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(6):586–90. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.153.6.586.

Okoro CA, Nelson DE, Mercy JA, Balluz LS, Crosby AE, Mokdad AH. Prevalence of household firearms and firearm-storage practices in the 50 states and the District of Columbia: findings from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2002. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):e370–6. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-0300.

Smith TW, Son J. Trends in gun ownership, 1972–2014. Chicago, IL; 2015. http://www.norc.org/PDFs/GSS Reports/GSS_TrendsinGunOwnership_US_1972–2014.pdf. Accessed 2 March 2018

Azrael D, Hepburn L, Hemenway D, Miller M. The stock and flow of US firearms: results from the 2015 National Firearms Survey. RSF Russell Sage Found J Soc Sci. 2017;3(5):38–57. https://doi.org/10.7758/rsf.2017.3.5.02.

Weil DS, Hemenway D. Loaded guns in the home. Analysis of a national random survey of gun owners. JAMA. 1992;267(22):3033–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.267.22.3033.

Crifasi CK, Doucette ML, McGinty EE, Webster DW, Barry CL. Storage practices of US gun owners in 2016. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(4):532–7. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304262.

McCarthy J. More than six in 10 Americans say guns make homes safer. Gallup. http://news.gallup.com/poll/179213/six-americans-say-guns-homes-safer.aspx. Published 2014. Accessed March 15, 2018.

Miller M, Hepburn L, Azrael D. Firearm acquisition without background checks: results of a national survey. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(4):233–9. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-1590.

Callegaro M, Disogra C. Computing response metrics for online panels. Public Opin Q. 2008;72(5):1008–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfn065.

von Elm E, Altman D, Egger M, Pocock S, Gotzche P, Vandenbroucke J, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:573–7. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010.

US Census. https://www.census.gov/data.html. Accessed March 15, 2018.

Johnson RM, Coyne-Beasley T, Runyan CW. Firearm ownership and storage practices, US households, 1992–2002. A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(2):173–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.015.

Hemenway D, Solnick SJ, Azrael DR. Firearm training and storage. JAMA. 1995;273(1):46–50. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1995.03520250062035.

Johnson RM, Miller M, Vriniotis M, Azrael D, Hemenway D. Are household firearms stored less safely in homes with adolescents?: analysis of a national random sample of parents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(8):788–92. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.160.8.788.

Ludwig J, Cook PJ, Smith TW. The gender gap in reporting household gun ownership. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(11):1715–8. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.88.11.1715.

Azrael D, Miller M, Hemenway D. Are household firearms stored safely? It depends on whom you ask. Pediatrics. 2000;106(3):E31. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.106.3.e31.

Powell KE, Jacklin BC, Nelson DE, Bland S. State estimates of household exposure to firearms, loaded firearms, and handguns, 1991 through 1995. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(6):969–72. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.88.6.969.

Simonetti J, Azrael D, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Miller M. Firearm storage practices and risk perceptions among a nationally representative of US Veterans with and without self harm risk factors. SLTB. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12463https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12463

Marsden P, Wright J. In: 2nd, editor. Handbook of survey research. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing; 2010.

Kreuter F, Presser S, Tourangeau R. Social desirability bias in CATI, IVR, and Web Surveys: the effects of mode and question sensitivity. Public Opin Q. 2008;72(5):847–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfn063.

Chang L, Krosnick J. National surveys via RDD telephone interviewing versus the internet: comparing sample representativeness and response quality. Public Opin Q. 2009;73(4):641–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfp075.

Kellermann AL, Rivara FP, Banton J, Reay D, Fligner CL. Validating survey responses to questions about gun ownership among owners of registered handguns. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131(6):1080–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115600.

Rafferty AP, Thrush JC, Smith PK, McGee HB. Validity of a household gun question in a telephone survey. Public Health Rep. 1995;110(3):282–8.

Betz ME, Barber C, Miller M. Suicidal behavior and firearm access: results from the second injury control and risk survey. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2011;41(4):384–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00036.x.

Acknowledgments

New Venture Fund fund for a Safer Future GA004695. The authors would like to thank Joseph Wertz and Andrew Conner for their contributions to the authors’ early thinking about this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Azrael, D., Cohen, J., Salhi, C. et al. Firearm Storage in Gun-Owning Households with Children: Results of a 2015 National Survey. J Urban Health 95, 295–304 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-018-0261-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-018-0261-7