Abstract

Prescribed fire is a primary tool used to restore western forests following more than a century of fire exclusion, reducing fire hazard by removing dead and live fuels (small trees and shrubs). It is commonly assumed that the reduced forest density following prescribed fire also reduces competition for resources among the remaining trees, so that the remaining trees are more resistant (more likely to survive) in the face of additional stressors, such as drought. Yet this proposition remains largely untested, so that managers do not have the basic information to evaluate whether prescribed fire may help forests adapt to a future of more frequent and severe drought.

During the third year of drought, in 2014, we surveyed 9950 trees in 38 burned and 18 unburned mixed conifer forest plots at low elevation (<2100 m a.s.l.) in Kings Canyon, Sequoia, and Yosemite national parks in California, USA. Fire had occurred in the burned plots from 6 yr to 28 yr before our survey. After accounting for differences in individual tree diameter, common conifer species found in the burned plots had significantly reduced probability of mortality compared to unburned plots during the drought. Stand density (stems ha−1) was significantly lower in burned versus un-burned sites, supporting the idea that reduced competition may be responsible for the differential drought mortality response. At the time of writing, we are not sure if burned stands will maintain lower tree mortality probabilities in the face of the continued, severe drought of 2015. Future work should aim to better identify drought response mechanisms and how these may vary across other forest types and regions, particularly in other areas experiencing severe drought in the Sierra Nevada and on the Colorado Plateau.

Resumen

El fuego prescripto es una herramienta primordial utilizada para restaurar los bosques del oeste de los EEUU luego de más de una centuria de exclusión del fuego, reduciendo el peligro de incendios mediante la remoción de combustibles vivos y muertos (pequeños árboles y arbustos). Se asume comúnmente que la reducción en la densidad del bosque luego de un fuego prescripto también reduce la competencia por los recursos entre los árboles remanentes, de manera tal que éstos son más resistentes (tienen más probabilidad de sobrevivir) frente a un estrés adicional como la sequía. Sin embargo esta suposición permanece aún sin verificar, por lo cual los gestores no tienen información básica para evaluar si el fuego prescripto puede ayudar a los bosques a adaptarse a un futuro con sequías más frecuentes y severas.

Durante el tercer año de sequía, en 2014, relevamos datos de 9950 árboles en 38 parcelas quemadas y 18 parcelas sin quemar en bosques mixtos de coniferas de elevaciones bajas (<2100 msnm) en los parques nacionales de Kings Canyon, Sequoia, y Yosemite en California, EEUU. El fuego había ocurrido en las parcelas quemadas entre 6 años y 28 años antes de nuestro relevamiento. Después de considerar las diferencias en el diámetro individual de los árboles y durante la sequía, las especies de coníferas encontradas en las parcelas quemadas redujeron significativamente la probabilidad de muerte comparadas con las parcelas no quemadas. La densidad del rodal (fustes ha−1) fue significativamente menor en sitios quemados versus los no quemados, apoyando la idea que una reducción en la competencia puede ser la responsable de la mortalidad diferencial en respuesta a la sequía. En el momento de escribir este artículo, no estamos seguros si los rodales quemados mantendrán una mortalidad baja en vistas a la sequía continua y severa de 2015. El trabajo a futuro debería apuntar a identificar mejor los mecanismos de respuesta a la sequía y como éstos pueden variar en otros tipos de bosques y regiones, particularmente en otras áreas que están experimentando sequías severas en Sierra Nevada y en la meseta de Colorado.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Drought is a major disturbance agent in forest ecosystems, causing tree mortality directly (Adams et al. 2009) or by making trees more vulnerable to insects (bark beetles) or pathogens (Weed et al. 2013). While reduced precipitation often defines drought, higher temperatures lead to increased evapotranspiration that also causes drought stress. Indeed, chronic drought caused by long-term warming trends is believed to be an underlying cause of increased “background” (non-catastrophic) tree mortality across western North America (van Mantgem et al. 2009, Peng et al. 2011). Recent observations from the American Southwest have shown that the co-occurrence of reduced precipitation and high temperatures—“hotter drought” (Allen et al. 2015)—can lead to massive forest die-back, in which entire stands are lost (Breshears et al. 2005, Allen et al. 2010).

Fire exclusion has also led to unforeseen changes in many western forests, particularly in those forests that historically experienced high frequency and low severity fire (Allen et al. 2002, Brown et al. 2004, Agee and Skinner 2005, Noss et al. 2006). Fire exclusion in these forests has typically resulted in high fuel accumulations, high densities of trees, and increasing dominance of fire-intolerant species. In response, many public land agencies support large prescribed fire programs aimed at reducing understory fuels and forest density. Prescribed fire has been generally successful at reducing severe fire hazard (van Wagtendonk 1996, Hurteau and North 2009, Fulé et al. 2012) by removing surface fuels, along with shrubs and small trees (ladder fuels). It is commonly assumed that following fire there is less competition among remaining trees so that they have increased resistance (more likely to survive) to additional stressors, such as drought.

Published findings on mechanical thinning and drought response provide mixed results. Thomas and Waring (2014) suggested that mechanical thinning treatments conferred improved forest resistance (remaining unchanged when subjected to disturbance) and resilience (capacity to return to original conditions) to drought. Other work suggests that the influence of mechanical thinning may be conditional on timing of treatments, the size structure of residual trees, and potential threshold responses (D’Amato et al. 2013). Moreover, the response of individual trees to drought is likely complex, partially dependent on local competitive environments and cumulative impacts of past drought events (Macalady and Bugmann 2014).

Can prescribed fire create conditions that enhance forest drought resistance? The answer to this question has profound implications for forest management over the coming decades. Drought-induced forest decline was identified as a key emerging threat to US forests in the recent National Climate Assessment (Joyce et al. 2014). Indeed, drought is expected to be more frequent and severe in coming decades across the southwestern United States (Garfin et al. 2014, Cook et al. 2015), underscoring the importance for land management agencies to develop cost-effective adaptation strategies to drought (Millar et al. 2007). Prescribed fire may serve as an adaptation tool, helping forests withstand expected warmer and drier future conditions, but this effect remains largely untested. California is currently experiencing its most severe drought in at least the last 120 years, and perhaps as much as a millennium, driven by low precipitation and record high temperatures (Griffin and Anchukaitis 2014). Aerial observations across California suggest that by 2014 forests at lower elevations experienced significant drought stress (Asner et al. 2016). We used this drought as a natural experiment, assessing whether or not past prescribed fires were associated with increased drought resistance (reduced tree mortality) in low elevation forests (<2100 m a.s.l.) at three national parks in the southern Sierra Nevada of California, USA.

Methods

Study Area

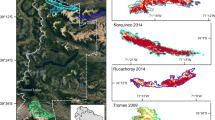

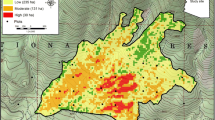

We sampled burned and unburned mixed conifer forests in Kings Canyon, Sequoia, and Yosemite national parks (Table 1, Figure 1). Lower elevation forests at these parks were observed to be responding to drought with elevated mortality by 2014 (Figure 2), while forests at higher elevations did not visibly display elevated mortality by 2014. Prior to the initiation of a prescribed burn program or the management of lightning ignited fires by the parks in the late 1960s, these forests generally had not burned since the 1860s or 1870s (Schwilk et al. 2006, Swetnam et al. 2009). The climate of this area is mediterranean, with wet, snowy winters and long, dry summers. The weather station at Grant Grove (2011 m elevation a.s.l.), near the majority of our plots, reported annual average minimum and maximum air temperatures of 1.9 °C and 13.6 °C, and mean annual precipitation of 109 cm (30 yr average, 1951 to 1980). Compared to these long-term averages, 2013 and 2014 were unusually hot and dry. Average annual minimum and maximum air temperatures for these years were 3.1 °C and 15.8 °C, with mean annual precipitation of 59 cm. The Yosemite Valley weather station (1210 m elevation a.s.l.) reported similar trends.

Data Sources

We used two primary data sources for this project: the US Geological Survey-led Sierra Nevada Forest Dynamics Plot Network (van Mantgem and Stephenson 2007) and the National Park Service fire effects monitoring (FMH) plots for Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks (NPS 2003). The Sierra Nevada Forest Dynamics Plot Network is a globally unique and ongoing plot-based forest monitoring project that has annually tracked the birth, death, and growth of nearly 30 000 individual trees across all major forest types on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada since the early 1980s. This network includes several plots in low elevation forests with and without a recent history of prescribed fire. The FMH fire effects monitoring data records forest conditions before and after prescribed fire. Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks were early adopters of these fire-effects monitoring protocols and have maintained an active program since the 1980s. Stand conditions at these sites differ according to pre-fire conditions and variability in fire effects. This plot-based program also tracks individual tree birth, death and growth, but at staggered intervals (typically pre-fire, and post fire at 0-, 1-, 2-, 5-, 10-year intervals, and every 10 yr thereafter).

There are a number of unburned FMH plots, established as unburned reference sites or prior to a prescribed fire that then did not occur. A major difference between these monitoring programs is plot size, with the Sierra Nevada Forest Dynamics plots generally at 1.0 ha, and the FMH plots at 0.1 ha. However, model testing did not provide evidence for systematic differences between individual tree response in the Sierra Nevada Forest Dynamics and FMH plot networks. Similarly, the single large plot at Yosemite National Park was composed of the same vegetation type as the other plots, met our criteria for analysis, and testing did not reveal significant differences in the mortality response in this plot compared to the plots found in Kings Canyon and Sequoia national parks.

In 2014, we conducted mortality assessments of trees that had died in 2013 or 2014 for individually marked trees in mixed conifer forests at all Sierra Nevada Forest Dynamics plots, and all FMH plots at Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks. We considered only low elevation forests, here defined as <2100 m a.s.l., which is the upper elevation boundary of ponderosa pine forests in the southern Sierra Nevada (Fites-Kaufman et al. 2007). We wanted to avoid measuring fire-caused tree mortality, and so excluded plots that had been burned ≤5 yr prior (van Mantgem et al. 2011). We focused on tree survivorship as an immediate drought response, noting if individual trees were alive or dead (no green needles). For the Sierra Nevada Forest Dynamics plots, annual assessments of tree mortality allowed observations of the exact year in which tree mortality occurred. Assessing trees that had died in 2013 or 2014 in the FMH plots was less straightforward; we excluded trees that were listed as dead in previous years and counted trees as newly dead within the past two years if they were retaining dead reddish needles and did not have a past history of severe crown scorch (>90 % crown volume scorch). Dead trees meeting these criteria in the FMH plots were scarce, so to increase our sample size of dead trees we expanded each side of the FMH plot by 10 m, covering an additional 0.18 ha to search for dead trees only. Our final sample was 9353 live trees and 415 dead trees in 38 burned and 18 unburned plots at Kings Canyon, Sequoia, and Yosemite national parks. Fire had occurred in the burned plots from 6 yr to 28 yr before our survey. For a subset of our plots, prescribed fire had been applied once (14 plots) or twice (4 plots) prior to the most recent prescribed fire. A history of repeated prescribed fire did not appear to influence our results.

Analyses

We compared burned and unburned plots in terms of stem density (trees ha−1), stand basal area (m2 ha−1), and quadratic mean diameter using randomization tests, creating 1000 samples with replacement (Manly 1997). We compared the proportion of stem density composed of dead versus live trees in burned and unburned stands with logistic regression, using a quasi-binomial response distribution to account for overdispersion. While this analysis shows differences in the observations of tree mortalities between burned and unburned plots, these differences may arise from the un-burned plots having greater numbers of small trees that may be at higher risk of mortality. To account for differences across stem sizes, we estimated individual tree mortality probabilities for our most common conifer species, which included white fir (ABCO, Abies con-color [Gordon & Glend.] Lindley, n = 3759 live trees and 123 dead trees), incense cedar (CADE, Calocedrus decurrens [Torrey] Florin, n = 3021 live trees and 152 dead trees), sugar pine (PILA, Pinus lambertiana Douglas, n = 777 live trees and 59 dead trees), and ponderosa pine (PIPO, P. ponderosa Laws, n = 428 live trees and 39 dead trees). Other conifers were sparse (generally fewer than 100 individuals) or lacked observations of mortality. We used generalized linear mixed models (GLMM, Gelman and Hill 2007) to estimate individual tree mortality probabilities, which allows us to analyze tree status (0 = live, 1 = dead), considering both individual-level variables (characteristics of individual trees) and plot-level variation. Our base model estimated two-year (2013 and 2014) mortality probability mij of tree i in plot j as:

where logDBH is the log-transformed (base 10) DBH (stem diameter at breast height, 1.37 m), and Spp is an indicator variable for species identity, with white fir (ABCO) used as the reference species. The variable aj represents plot-level variations in the regression intercept. We considered varying-intercepts with varying-slope models, but these formulations did not improve model performance. We evaluated improvements to this base model with additional variables, including a term for a history of prescribed burning.

Selection for the GLMMs was done using the Akaike Information Criterion adjusted for sample size (AICc) (Burnham and Anderson 2002), with differences in AICc (ΔAICc) >2 used as evidence of substantial model dissimilarity. We used the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC, Saveland and Neuenschwander 1990) to characterize candidate model accuracy (predicted proportions of Type I and Type II errors), with values of AUC >0.70 suggesting acceptable model accuracy (Hosmer and Lemeshow 2000). Model fit was checked by binning the data and plotting average predicted mortality probability against the observed proportion of dead trees. The proportion of variation explained using the individual-level variables only (marginal R2) and the combined individual- and plot-level variables (conditional R2) of the fitted models were calculated following Nakagawa and Schielzeth (2013). We calculated bootstrapped (1000 realizations) confidence intervals for parameter estimates from the models with the best support according to AICc. Analyses were conducted using the R statistical language (R Development Core Team 2015) with the lme4 (Bates et al. 2015) and MuMIn (Barton 2015) packages.

Results

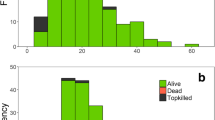

The burned and unburned plots were different in some dimensions of stand condition in 2014 (Table 1). The average length of time since prescribed fire in the burned plots was 15 yr, while the unburned plots likely had not experienced fire for >100 yr (Schwilk et al. 2006, Swetnam et al. 2009). The burned plots had lower average stem density in the burned plots compared to the unburned plots (randomization test, P = 0.001). In contrast, burned plots had slightly higher average basal area compared to unburned plots, but this difference was non-significant (randomization test, P = 0.417). Quadratic mean diameter was greater in the burned plots compared to the unburned plots (randomization test, P = 0.001). Logistic regression indicated that the density of recently dead trees was negatively related to a history of prescribed fire (β BurnStatus ± 1 SE = −1.62 ± 0.44, P <0.001).

GLMM results showed that the two-year (2013 and 2014) probability of individual tree mortality varied by tree size (logDBH), species identity (Spp), and history of prescribed burning (BurnStatus) (Tables 2 and 3). Common conifer species appeared to respond somewhat individualistically to a history of prescribed burning (i.e., there was support for Spp × BurnStatus interaction terms), with Pinus species having the greatest sensitivity to history of prescribed burning. Individual tree mortality probabilities also varied substantially with size among species. Residual plots did not suggest model misspecifications and AUC = 0.77. Adding an additional term for the years since prescribed burning was not supported (ΔAICc = 0.19). The individual-level effects of the model explained a relatively low amount of variation in tree mortality (marginal R2 = 0.11), although the inclusion of the plot-level effect improved the model performance (conditional R2 = 0.37). Excluding the BurnStatus term resulted in a relatively large proportional reduction in the marginal R2 (marginal R2 = 0.05). Prediction plots show that trees in plots that experienced prescribed fire had lower mortality probabilities (with some overlap in confidence intervals, particularly for white fir), and that these differences were most pronounced in small trees (Figure 3).

Discussion

Our results suggest that a common forest restoration tool, prescribed fire, may increase resistance to drought. After accounting for differences in individual tree diameter, common conifer species found in plots with a history of prescribed fire had significantly reduced mortality probabilities compared to trees in unburned plots. Small trees had high mortality probabilities, but the effect of past prescribed fire did not appear to be dependent on tree size (i.e., there was not strong support for an interaction between logDBH and Burn-Status). The support for the interaction term between species identity and history of prescribed burning suggests that Pinus species may be particularly sensitive to changes in stand conditions. Stand density (stems ha−1) was significantly lower in burned versus un-burned sites, supporting the idea that reduced competition may be at least partly responsible for the differential drought mortality response. However, basal area (m2 ha−1) was not significantly lower in burned versus unburned sites, so the role of competition in determining the differential mortality response is not clear.

At the time of writing, we are not sure if burned stands will maintain lower tree mortality probabilities in the face of the continued, severe drought of 2015. Future work should aim to better identify drought response mechanisms. While the causal links among prescribed fire, reduced stand density, and reduced mortality under drought are intuitively appealing, our data were insufficient to test this directly. Plot sizes were generally too small (0.1 ha) to confidently measure individual-level competitive interactions (i.e., many trees will be at the plot margins, with unknown competitive environments outside of the plot boundary) (Das 2012). We also did not collect information on other potentially important mortality predictors, such as individual tree growth history (Das et al. 2007), insect and pathogen pressure, and plot-level environmental conditions (e.g., soil depth or water holding capacity). Future work should attempt to combine both direct and indirect influences of tree mortality across a broader geographic area, likely using a more sophisticated analytical framework such as structural equation models (Youngblood et al. 2009).

While reconstructing historical forest structure is problematic (Stephenson 1999), recent analyses of inventories of productive ponderosa pine forests conducted in 1911 for trees ≥15.2 cm DBH near our study sites identified average stand densities of 72.7 trees ha−1 and basal area of 21.5 m2 ha−1 (Collins et al. 2015). Using the same stem diameter range, our burned plots had an average stand density of 159 trees ha−1 and average basal area of 74.0 m2 ha−1. These statistics suggest that, even after prescribed burning, our forests contain many more trees relative to estimates of historical averages. It could be that forests with structures more closely approximating these presumed historical conditions may be more resistant and resilient (sensu Walker et al. 2004) to drought.

It may be possible to eventually manage for drought resistant and resilient forest structures. Such knowledge would provide a target when designing prescriptions using fire (perhaps in combination with mechanical thinning) under expected future climatic conditions. We currently do not know if prescribed fire prescriptions will need to be more aggressive to promote resistance and resilient to drought. If prescribed prescriptions do need to be more aggressive, how much and under what conditions? These are critical management concerns, as many regions in the western United States are expected to see increased frequency and intensity of both drought and wildfire (Littell et al. 2009, Williams et al. 2012, Cook et al. 2015). It may be possible that pre-scribed fire can serve as an adaptation tool for both of these threats, using existing resources and human capital. Yet many barriers exist to maintaining, let alone expanding, the deployment of prescribed fire, particularly logistical constraints and air quality concerns (Ryan et al. 2013). Our study also underscores the need to maintain plot-based forest monitoring networks, in both treated and untreated stands, to gauge the success of prescribed fire. Overcoming obstacles to the use of prescribed fire may prove crucial to the future integrity of western forests.

Literature Cited

Adams, H.D., M. Guardiola-Claramonte, G.A. Barron-Gafford, J.C. Villegas, D.D. Breshears, C.B. Zou, P.A. Troch, and T.E. Huxman. 2009. Temperature sensitivity of drought-induced tree mortality portends increased regional die-off under global-change-type drought. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106: 7063–7066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901438106

Agee, J.K., and C.N. Skinner. 2005. Basic principles of forest fuel reduction treatments. Forest Ecology and Management 211: 83–96. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2005.01.034

Allen, C.D., D.D. Breshears, and N.G. McDowell. 2015. On underestimation of global vulnerability to tree mortality and forest die-off from hotter drought in the Anthropocene. Ecosphere 6(8): art129. doi: 10.1890/ES15-00203.1

Allen, C.D., A.K. Macalady, H. Chenchouni, D. Bachelet, N. McDowell, M. Vennetier, T. Kitzberger, A. Rigling, D.D. Breshears, E.H. Hogg, P. Gonzalez, R. Fensham, Z. Zhang, J. Castro, N. Demidova, J.-H. Lim, G. Allard, S.W. Running, A. Semerci, and N. Cobb. 2010. A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. Forest Ecology and Management 259: 660–684. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2009.09.001

Allen, C.D., M. Savage, D.A. Falk, K.F. Suckling, T.W. Swetnam, T. Schulke, P.B. Stacey, P. Morgan, M. Hoffman, and J.T. Klingel. 2002. Ecological restoration of southwestern ponderosa pine ecosystems: a broad perspective. Ecological Applications 12: 1418–1433. doi: 10.1890/1051-0761(2002)012[1418:EROSPP]2.0.CO;2

Asner, G.P., P.G. Brodrick, C.B. Anderson, N. Vaughn, D.E. Knapp, and R.E. Martin. 2016. Progressive forest canopy water loss during the 2012–2015 California drought. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113: E249–E255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523397113

Barton, K. 2015. MuMIn: Multi-Model Inference. R package version 1.15.1. <http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MuMIn>. Accessed 14 April 2013.

Bates, D., M. Mächler, B. Bolker, and S. Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67: 1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Breshears, D.D., N.S. Cobb, P.M. Rich, K.P. Price, C.D. Allen, R.G. Balice, W.H. Romme, J.H. Kastens, M.L. Floyd, J. Belnap, J.J. Anderson, O.B. Myers, and C.W. Meyer. 2005. Regional vegetation die-off in response to global-change-type drought. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America 102: 15144–15148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505734102

Brown, R.T., J.K. Agee, and J.F. Franklin. 2004. Forest restoration and fire: principles in the context of place. Conservation Biology 18: 903–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.521_1.x

Burnham, K.P., and D.R. Anderson. 2002. Model selection and multimodel inference. Second edition. Springer-Verlag, New York, New York, USA.

Collins, B.M., J.M. Lydersen, R.G. Everett, D.L. Fry, and S.L. Stephens. 2015. Novel characterization of landscape-level variability in historical vegetation structure. Ecological Applications 25: 1167–1174. doi: 10.1890/14-1797.1

Cook, B.I., T.R. Ault, and J.E. Smerdon. 2015. Unprecedented 21st century drought risk in the American Southwest and Central Plains. Science Advances 1(1): e1400082. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1400082

D’Amato, A.W., J.B. Bradford, S. Fraver, and B.J. Palik. 2013. Effects of thinning on drought vulnerability and climate response in north temperate forest ecosystems. Ecological Applications 23: 1735–1742. doi: 10.1890/13-0677.1

Das, A. 2012. The effect of size and competition on tree growth rate in old-growth coniferous forests. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 42: 1983–1995. doi: 10.1139/x2012-142

Das, A., J. Battles, N.L. Stephenson, and P.J. van Mantgem. 2007. The relationship between tree growth patterns and likelihood of mortality: a study of two tree species in the Sierra Nevada. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 37: 580–597. doi: 10.1139/X06-262

Fites-Kaufman, J., P. Rundel, N. Stephenson, and D.A. Weixelman. 2007. Montane and subalpine vegetation of the Sierra Nevada and Cascade ranges. Pages 456–501 in M. Barbour, T. Keeler-Wolf, and A.A. Schoenherr, editors. Terrestrial vegetation of California, third edition. University of California Press, Berkeley, USA. doi: 10.1525/california/9780520249554.003.0017

Fulé, P.Z., J.E. Crouse, J.P. Roccaforte, and E.L. Kalies. 2012. Do thinning and/or burning treatments in western USA ponderosa or Jeffrey pine-dominated forests help restore natural fire behavior? Forest Ecology and Management 269: 68–81. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2011.12.025

Garfin, G., G. Franco, H. Blanco, A. Comrie, P. Gonzalez, T. Piechota, R. Smyth, and R. Waskom. 2014. National climate assessment: Southwest region. Pages 462–486 in J.M. Melillo, T.C. Richmond, and G.W. Yohe, editors. Climate change impacts in the United States: the third national climate assessment. US Global Change Research Program, Washington, D.C., USA.

Gelman, A., and J. Hill. 2007. Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. Cambridge University Press, New York, New York, USA.

Griffin, D., and K.J. Anchukaitis. 2014. How unusual is the 2012–2014 California drought? Geophysical Research Letters 41: 9017–9023. doi: 10.1002/2014GL062433

Hosmer, D.W., and S. Lemeshow. 2000. Applied logistic regression. Second edition. John Wiley & Sons, New York, New York, USA. doi: 10.1002/0471722146

Hurteau, M., and M. North. 2009. Fuel treatment effects on tree-based forest carbon storage and emissions under modeled wildfire scenarios. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 7: 409–414. doi: 10.1890/080049

Joyce, L.A., S.W. Running, D.D. Breshears, V.H. Dale, R.W. Malmsheimer, R.N. Sampson, B. Sohngen, and C.W. Woodall. 2014. Forests. Pages 175–194 in J.M. Melillo, T.C. Richmond, and G.W. Yohe, editors. Climate change impacts in the United States: the third national climate assessment. US Global Change Research Program, Washington, D.C., USA.

Littell, J.S., D. McKenzie, D.L. Peterson, and A.L. Westerling. 2009. Climate and wildfire area burned in western US ecoprovinces, 1916–2003. Ecological Applications 19: 1003–1021. doi: 10.1890/07-1183.1

Macalady, A.K., and H. Bugmann. 2014. Growth-mortality relationships in piñon pine (Pinus edulis) during severe droughts of the past century: shifting processes in space and time. PloS ONE 9(5): e92770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092770

Manly, B.F.J. 1997. Randomization, bootstrap and Monte Carlo methods in biology. Second edition. Chapman and Hall/CRC, Boca Raton, Florida, USA.

Millar, C.I., N.L. Stephenson, and S.L. Stephens. 2007. Climate change and forests of the future: managing in the face of uncertainty. Ecological Applications 17: 2145–2151. doi: 10.1890/06-1715.1

Nakagawa, S., and H. Schielzeth. 2013. A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from generalized linear mixed-effects models. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 4: 133–142. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-210x.2012.00261.x

Noss, R.F., J.F. Franklin, W.L. Baker, T. Schoennagel, and P.B. Moyle. 2006. Managing fire prone forests in the western United States. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 8: 481–487. doi: 10.1890/1540-9295(2006)4[481:MFFITW]2.0.CO;2

NPS [National Park Service]. 2003. Fire monitoring handbook. Fire Management Program Center, National Interagency Fire Center, Boise, Idaho, USA.

Peng, C., Z. Ma, X. Lei, Q. Zhu, H. Chen, W. Wang, S. Liu, W. Li, X. Fang, and X. Zhou. 2011. A drought-induced pervasive increase in tree mortality across Canada’s boreal forests. Nature Climate Change 1: 467–471. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1293

R Development Core Team. 2015. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

Ryan, K.C., E.E. Knapp, and J.M. Varner. 2013. Prescribed fire in North American forests and woodlands: history, current practice, and challenges. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 11: e15–e24. doi: 10.1890/120329

Saveland, J.M., and L.F. Neuenschwander. 1990. A signal detection framework to evaluate models of tree mortality following fire damage. Forest Science 36: 66–76.

Schwilk, D.W., E.E. Knapp, S.M. Ferrenberg, J.E. Keeley, and A.C. Caprio. 2006. Tree mortality from fire and bark beetles following early and late season prescribed fires in a Sierra Nevada mixed-conifer forest. Forest Ecology and Management 232: 36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2006.05.036

Stephenson, N.L. 1999. Reference conditions for giant sequoia forest restoration: structure, process, and precision. Ecological Applications 9: 1253–1265. doi: 10.1890/1051-0761(1999)009[1253:RCFGSF]2.0.CO;2

Swetnam, T.W., C.H. Baisan, A.C. Caprio, P.M. Brown, R. Touchan, R.S. Anderson, and D.J. Hallett. 2009. Multi-millennial fire history of the Giant Forest, Sequoia National Park, California, USA. Fire Ecology 5(3): 120–150. doi: 10.4996/fireecology.0503120

Thomas, Z., and K.M. Waring. 2014. Enhancing resiliency and restoring ecological attributes in second-growth ponderosa pine stands in northern New Mexico, USA. Forest Science 61: 93–104.

van Mantgem, P.J., and N.L. Stephenson. 2007. Apparent climatically-induced increase of mortality rates in a temperate forest. Ecology Letters 10: 909–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01080.x

van Mantgem, P. J., N.L. Stephenson, J.J. Battles, E.K. Knapp, and J.E. Keeley. 2011. Long-term effects of prescribed fire on mixed conifer forest structure in the Sierra Nevada, California. Forest Ecology and Management 261: 989–994. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2010.12.013

van Mantgem, P.J., N.L. Stephenson, J.C. Byrne, L.D. Daniels, J.F. Franklin, P.Z. Fulé, M.E. Harmon, A.J. Larson, J.M. Smith, A.H. Taylor, and T.T. Veblen. 2009. Widespread increase of tree mortality rates in the western United States. Science 323: 521–524. doi: 10.1126/science.1165000

van Wagtendonk, J.W. 1996. Use of a deterministic fire model to test fuel treatments. Pages 1155–1167 in: D.C. Erman, editor. Sierra Nevada Ecosystem Project, final report to Congress, volume II. Wildlands Resources Center Report No. 37, Centers for Water and Wildlands Resources, University of California, Davis, USA.

Walker, B., C.S. Holling, S.R. Carpenter, and A. Kinzig. 2004. Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social-ecological systems. Ecology and Society 9(2): 5.

Weed, A.S., M.P. Ayres, and J.A. Hicke. 2013. Consequences of climate change for biotic disturbances in North American forests. Ecological Monographs 83: 441–470. doi: 10.1890/13-0160.1

Williams, A.P., C.D. Allen, A.K. Macalady, D. Griffin, C.A. Woodhouse, D.M. Meko, T.W. Swetnam, S.A. Rauscher, R. Seager, H.D. Grissino-Mayer, J.S. Dean, E.R. Cook, C. Gangodagamage, M. Cai, and N.G. McDowell. 2012. Temperature as a potent driver of regional forest drought stress and tree mortality. Nature Climate Change 3: 292–297. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1693

Youngblood, A., J. Grace, and J. McIver. 2009. Delayed conifer mortality after fuel reduction treatments: interactive effects of fuel, fire intensity, and bark beetles. Ecological Applications 19: 321–337. doi: 10.1890/07-1751.1

Acknowledgements

We thank the many field crews who collected and organized the forest plot data. P. Moore, J. Yee, and three anonymous reviewers provided helpful comments on the manuscript. This project was partially supported by the National Park Service and the US Geological Survey Southwest Climate Science Center. Any use of trade names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the US government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van Mantgem, P.J., Caprio, A.C., Stephenson, N.L. et al. Does Prescribed Fire Promote Resistance to Drought in Low Elevation Forests of the Sierra Nevada, California, USA?. fire ecol 12, 13–25 (2016). https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.1201013

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.1201013