Abstract

Many (inter)national standards exist to evaluate the resistance of mortar and concrete to carbonation. When a carbonation coefficient is used for performance comparison of mixtures or service life prediction, the applied boundary conditions during curing, preconditioning and carbonation play a crucial role, specifically when using latent hydraulic or pozzolanic supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs). An extensive interlaboratory test (ILT) with twenty two participating laboratories was set up in the framework of RILEM TC 281-CCC ‘Carbonation of Concrete with SCMs’. The carbonation depths and coefficients determined by following several (inter)national standards for three cement types (CEM I, CEM II/B-V, CEM III/B) both on mortar and concrete scale were statistically compared. The outcomes of this study showed that the carbonation rate based on the carbonation depths after 91 days exposure, compared to 56 days or less exposure duration, best approximates the slope of the linear regression and those 91 days carbonation depths can therefore be considered as a good estimate of the potential resistance to carbonation. All standards evaluated in this study ranked the three cement types in the same order of carbonation resistance. Unfortunately, large variations within and between laboratories complicate to draw clear conclusions regarding the effect of sample pre-conditioning and carbonation exposure conditions on the carbonation performance of the specimens tested. Nevertheless, it was identified that fresh and hardened state properties alone cannot be used to infer carbonation resistance of the mortars or concretes tested. It was also found that sealed curing results in larger carbonation depths compared to water curing. However, when water curing was reduced from 28 to 3 or 7 days, higher carbonation depths compared to sealed curing were observed. This increase is more pronounced for CEM I compared to CEM III mixes. The variation between laboratories is larger than the potential effect of raising the CO2 concentration from 1 to 4%. Finally, concrete, for which the aggregate-to-cement factor was increased by 1.79 in comparison with mortar, had a carbonation coefficient 1.18 times the one of mortar.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

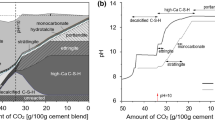

Working groups 1 and 2 of RILEM TC 281–CCC “Carbonation of concrete with supplementary cementitious materials” are studying the effect of SCMs on natural and accelerated carbonation of blended Portland cements and the correlation between atmospheric carbonation and carbonation induced by accelerated testing at high CO2 concentrations, respectively. The higher susceptibility of blended cements, where Portland cement (PC) clinker is partially replaced by SCMs, to carbonation is usually observed when adopting accelerated tests described in standards and methods internationally applied [1,2,3,4,5,6]. The elevated CO2 concentrations in such tests generally range from 1 to 20% and can even reach 100% which is a much broader and a higher value range than can be achieved during service conditions. Nonetheless, comparison of carbonation at various elevated and natural CO2 concentrations shows important consequences on the carbonation mechanisms and reaction products formed [1, 7]. Above 3% of CO2, calcium silicate hydrates (C–S–H) can fully decompose into calcium modified silica gel, while below this concentration, partially decalcified C–S–H was found after the completion of carbonation [1, 8,9,10,11]. Also the formation of amorphous calcium carbonate or specific calcium carbonate polymorphs (calcite, vaterite or aragonite) depends amongst other parameters on the CO2 concentration [12,13,14,15]. Moreover, at high CO2 concentrations, excessive water production during carbonation can result in a pore blocking effect [16]. Relative humidity (RH) and temperature (temp) during tests also strongly differ from the varying meteorological conditions in reality. The impact of RH can be assigned to varying degrees of saturation of the pore structure influencing the diffusion and reaction rate of CO2 [17,18,19]. Consequently, based on the binder type, different optimal RH ranges are identified at which carbonation proceeds the fastest [1, 4, 6, 18, 19]. The binder and environmental dependency of the carbonation reaction mechanisms has a major impact on reaction kinetics, porosity and hence on the transport properties of the carbonated cement paste [1, 6]. Furthermore, different standards do not only differ with regard to the test conditions during carbonation (i.e. CO2 concentration, temperature and RH), but also with regard to the time of curing, curing conditions and sample pre-conditioning as well as sample sizes. In mortar or concrete made with SCMs, which are pozzolanic or latent-hydraulic, the reaction processes are often delayed. Assuming CO2 preferably interacts with calcium ions originating from hydrate phases [1, 4, 20], curing and pre-conditioning times and boundary conditions can have a significant impact on the test results [1, 5, 20]. Moreover, the total amount of CO2 that can be bound (binding or buffering capacity of a binder) depends directly on the amount of (reacted) CaO available [2]. Thus, the CO2 binding capacity of blended cements is generally lower than that of plain PC since the available CaO content is lower [4, 20]. Also the main reaction product during hydration of blended cements is an (Al-substituted) C–S–H type phase with lower Ca/Si ratio than in plain PC systems at the expense of portlandite [21, 22].

A thorough state-of-the-art literature review was conducted by the same working groups 1 and 2 of TC 281-CCC which served as the literature study for this ILT [1]. Given the fact that the carbonation exposure conditions and sample preparation induce significant changes in the carbonation mechanism and reaction products forming [1, 7], there is an urgent need for validating accelerated tests representative of what is observed under natural carbonation conditions. Although the ILT includes a test program for both accelerated and natural carbonation testing, the current paper only focusses on accelerated carbonation.

The overall aim of the ILT is to compare the outcomes obtained when adopting currently available standards for carbonation testing of mortar and concrete using three different types of cement (i.e. CEM I 42.5 N, CEM II/B-V 42.5 N and CEM III/B 42.5 N). This ILT was carried out to identify the following effects on carbonation resistance: (1) the effect of sample pre-conditioning, (2) the effect of CO2 concentration during accelerated carbonation and (3) the effect of coarse aggregates (mortar vs. concrete). The ILT will also (4) compare ranking of cement types following different carbonation standards and (5) enhance knowledge and awareness about the uncertainty of the results via the estimation of the repeatability and reproducibility variances. After processing natural carbonation results in a second phase of the ILT and based on the correlation between accelerated and natural carbonation, recommendations for optimized accelerated carbonation testing representative for the natural resistance to carbonation of mortar and concrete with SCMs will be proposed in a follow-up report.

2 Participants

Nineteen laboratories from Europe and three laboratories outside Europe participated in this ILT of which seventeen laboratories provided accelerated carbonation test results (indicated with an asterisk): University of Minho* (Portugal), University of Extremadura in collaboration with Instituto Eduardo Torroja (CSIC)* (Spain), Instituto Eduardo Torroja (CSIC) (Spain), Universitat Politecnica de Catalunya (UPC)* (Spain), Universidad Politecnica de Madrid (Spain), KU Leuven – Ghent Technology Campus* (Belgium), Belgian Nuclear Research Center—SCK-CEN* (Belgium), Magnel-Vandepitte Laboratory—Ghent University* (Belgium), University of Liege* (Belgium), TU Delft (The Netherlands), TU Munich* (Germany), RWTH Aachen University* (Germany), Empa* (Switzerland), TFB AG* (Switzerland), Graz University of Technology* (Austria), Slovenian National Building and Civil Engineering Institute—ZAG* (Slovenia), University of Belgrade* (Serbia), Democritus University of Thrace* (Greece), Bennett and Mahindra University* (India), Hunan University* (China), University of Lagos (Nigeria).

General guidelines regarding the mix design for mortar and concrete were provided in combination with general instructions on how to perform carbonation testing and measurements in case this was not imposed by the applied standard or method. The laboratories were assigned random letters A—V.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Materials

Three different cement types were provided by HeidelbergCement AG Germany: (1) CEM I 42.5 N (designated as CEM I), (2) CEM II/B-V 42.5 N (designated as CEM II) and (3) CEM III/B 42.5 N (designated as CEM III). The chemical and mineralogical compositions of the anhydrous cements are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively, and Table 2 also displays the physical and mechanical properties. Loss on ignition, Blaine fineness, density and compressive strength was determined according to EN 196-2 [23], EN 196-6 [24], EN 196-6 [24] and EN 196-1 [25], respectively. CEM I was applied by all participants and the application of CEM II and CEM III was up to participants choice. It is important to remark that cements used in this ILT were ground to a specific Blaine fineness to obtain the same strength class. This is a different approach compared to a lot of other studies where individual constituents (CEM I and partial replacement by fly ash (FA) or ground granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBFS)) with different finenesses and without further grinding are used as binder. These approaches have an important impact on the hydration reactions and kinetics, resulting in a different strength performance as well as carbonation mechanism. The cement was shipped in sealed containers to avoid undesirable aging and setting during shipping and storage. For mortar, CEN standard sand [25] was used and for the concrete mixes, every laboratory was responsible for the fine and coarse aggregate fractions based on predefined boundary conditions for the design grading curve (Sect. 3.1.2).

The three participating laboratories outside Europe (China, India and Nigeria) used their local cements with properties as close as possible to the three reference cement types (Online Resource 1 and 2). In this perspective, two options were applied in which market available cement types with equivalent strength classes were used (Online Resource 1 and 2 – equivalent CEM-a) or equivalent chemical composition was targeted (Online Resource 1 and 2—equivalent CEM-b) by combining individual constituents without further grinding. In the latter case, no equivalent strength classes were obtained. CEN standard sand or a locally available sand was used to prepare the mortar specimens (Online Resource 3).

3.1.1 Mortar

Mortar mixes were prepared following the procedure as mentioned in EN 196-1 [25], however, the composition deviated from the standard and consisted of 450 ± 2 g cement, 247.5 ± 1 g tap water and 1350 ± 5 g CEN standard sand. The water to cement (w/c) ratio for both mortar and concrete was set at 0.55. This value was selected based on the specifications for common exposure class XC3 defined in EN 206 [26] and guarantees considerable carbonation depths in the time frame of the ILT. Water dosage was not corrected for adsorbed and absorbed water. In case large batches were prepared by specific laboratories, a larger mortar or concrete mixer was used. Unless stated otherwise, in the applied carbonation standard, at least two different specimens were tested during accelerated carbonation with a specimen size of 40 × 40 × 160 mm3.

Per type of cement, one single measurement of consistence and air content of the mortar was performed according to EN 1015-3 [27] and EN 1015-7 [28], respectively. This means that in case small batches were made, the air content and consistence were not determined on all different batches. If mortar was made on different days, preferably consistence and air content were measured at least once per day per type of cement. In case large batches were made, it was strongly recommended to determine the fresh properties on each batch. For each type of cement evaluated, three prisms of 40 × 40 × 160 mm3 for flexural (Rf) and compressive (Rc) strength were produced to be tested after 28 days of water curing at 20 °C according to EN 196-1 [25].

3.1.2 Concrete

The concrete mix design was characterized by a binder content of 340 kg/m3 and a w/b ratio of 0.55. Round shaped siliceous aggregates with a maximum grain size of 16 mm were combined to approach the design grading curve. This design grading curve is based on similar and commonly produced Belgian concrete mixes which typically follow the B-C curve according to DIN 1045-2 [29] for sieves ≤ 2 mm and the A-B curves for sieves > 2 mm. An overview of the design grading curve and the actual grading curves of combined aggregates of the concrete produced by each of the participating laboratories is visualised in Online Resource 4. The water absorption of the aggregates was determined separately for all aggregate fractions according to EN 1097-6 [30]. Also possible adsorbed water on the surface of the aggregates was determined by oven drying at 105 °C. Water dosage was corrected for this water absorption and adsorption in contrast to the mortar specimens where no corrections for adsorbed and absorbed water was applied. A slump class S3 [26, 32] was targeted by the use of a naphthalene-based superplasticizer. Preparation, filling of moulds, compaction of the concrete and levelling of the surface was carried out following EN 12390-2 [31]. Unless stated otherwise in the applied carbonation standard, at least two different specimens with a specimen size of 100 × 100 × 400 mm3 were prepared for carbonation testing. Per concrete batch, one single measurement of consistence, density and air content was performed according to EN 12350-2 [32], EN 12350-6 [33] and EN 12350-7 [34], respectively. The sample was obtained in accordance to EN 12350-1 [35]. Per concrete batch, also at least three cubes 150 × 150 × 150 mm3 in accordance with EN 12350-1 [35] for compressive strength were cast and tested after 28 days of water curing at 20 °C according to EN 12390-3 [36]. Before testing, the excess moisture from the surface of the specimen was wiped before placing in the testing machine. Specimens were tested within 1 h after removal from the curing environment.

3.2 Methods

Both mortar and concrete specimens were exposed to elevated CO2 concentrations according to various (inter)national standards and methods. A summary of the reference method and different test methods applied by the participating laboratories is given in Table 3 in combination with the number of laboratories applying these methods for each cement and specimen type. Differences between methods are related to boundary conditions for curing, preconditioning and CO2 exposure. To analyse the impact of curing and CO2 concentration, test specimens were evaluated against reference specimens. All laboratories performed accelerated carbonation tests on reference specimens with following predefined curing (reference method): (1) specimens were wrapped airtight in cling film and stored at 20 ± 2 °C after casting, (2) demoulding after 24 h and (3) sealed curing of specimens in cling film and further storage for 27 days at 20 ± 2 °C until the age of 28 days. After the predefined curing, specimens were preconditioned according to the followed accelerated carbonation standard.

All specimens were exposed to elevated CO2 concentrations, according to the standard followed. Each standard defines the times at which carbonation depths should be determined. However, in order to be able to compare results, determination of the carbonation depths was carried out at least at the following times of exposure: 0–14–28–56–91 days. The carbonation depth was measured by spraying a colour indicator solution on a freshly broken surface. A phenolphthalein indicator solution comprising of 1 g of phenolphthalein indicator in a solution of 70 ml ethanol and 30 ml demineralized water was applied. Most standards for carbonation testing impose a restricted time between breaking, spraying and measuring the carbonation depth. General practice is to read the carbonation depth within 1 h ± 15 min after spraying a fine mist of the pH indicator on a freshly broken surface (dry specimens). The ILT, however, revealed that specifically for CEM I specimens, no clear colour change boundary could be observed after this restricted time due to leaching of the alkaline pore solution. Exposing the sprayed surface for longer than 24 h leads to a better distinguishable colour change boundary as can be seen in Fig. 1. In contrast to CEM I specimens, this observation cannot be extended to CEM II and CEM III specimens where directly after spraying, a relatively clear colour change boundary could be observed. Unfortunately, some laboratories postponed the reading of the carbonation depth, whereas other laboratories followed the guidelines and measured the colour change boundary within 1 h ± 15 min. Consequently, it is difficult to assess the impact of the time of reading on the carbonation depth and carbonation coefficients considered for this ILT analysis.

Example of CEM I mortar specimen (EN 13295—14 days exposure) after spraying with pH indicator and photographed after 60 min and 24 h, CEM II mortar specimen (EN 13295—25 days exposure) photographed after 60 min and 24 h and a CEM III mortar specimen (EN 13295—18 days exposure) photographed after 60 min

At least three measuring points per side were considered. These three points were evenly distributed in the zone with one dimensional ingress, which is called the level surface of the colour change boundary. In case a measuring point was located at a dense aggregate, the colour change boundary was imaginatively extended through the aggregate, connecting the limits on each side of the grain.

3.3 Data acquisition and selection

3.3.1 Carbonation depth versus carbonation coefficient

The standards applied in the framework of the ILT generally report on a carbonation depth after a specific exposure time. However, the resistance to carbonation used for service life prediction modelling is mostly expressed as a coefficient which is the relation between the carbonation depth as a function of the square root of time. The carbonation coefficient can be the result of one carbonation depth determination after a specific period or obtained after (linear) regression of several (whether or not averaged) determinations in time. The rate of CO2 ingress and carbonation can decrease and stabilise during prolonged exposure due to pore clogging as a result of CaCO3 formation, water release as a reaction product of carbonation of portlandite, varying carbonation kinetics based on the origin of Ca to react with CO2, …[1] A stabilization of the rate of CO2 ingress expressed as the carbonation depth as a function of the square root of time after a specific period is necessary to serve as a representative value for the resistance to carbonation. The final carbonation depth as an output of accelerated carbonation testing according to a certain standard for the calculation of the carbonation coefficient should therefore be considered carefully. Figure 2A–D show the box-and-whisker plots of the differences between the carbonation coefficient calculated as the slope after linear regression of the mean depths as a function of the square root of time (up to 91 days)(klin.reg.), and the slope forced through zero (corrected for possible initial carbonation depths at time 0) based on the measurements after 14 (k14 days), 28 (k28 days), 56 (k56 days) or 91 days (k91 days), respectively, for all test regimes on both mortar and concrete scale performed by each laboratory (conceptual methodology in Online Resource 5). It can be concluded that the carbonation rates based on the carbonation depths after 91 days exposure show the lower deviation compared with the slope of the linear regression, and therefore it can be considered that these values serve as a good estimate of the potential resistance to carbonation of the materials tested. Comparison of the accelerated carbonation standards reporting on carbonation depths will consequently be based on the mean carbonation depths obtained after 91 days of exposure to an elevated CO2 concentration (Sect. 4.2).

Box-and-whisker plot of the differences between the carbonation coefficient expressed as the slope after linear regression of the mean depths as a function of the square root of time (up to 91 days) (klin. reg.) and the slope based on the measurements after A 14 (k14 days), B 28 (k28 days), C 56 (k56 days) and D 91 days (k91 days) for all test regimes on both mortar and concrete scale performed by each laboratory

3.3.2 Impact of measuring side

It is generally known that the microstructure and composition of the cast sides can differ considerably from the trowelled side. Therefore, the carbonation depths of each of the four measuring sides, after 91 days of accelerated carbonation, were statistically compared. This analysis was performed for each test method and laboratory individually by comparing the mean carbonation depth of the two or three repetitions for each side with each other. Consequently, for the laboratories which conducted only two repetitions, the homoscedasticity based on the Levene’s test could not be assessed. In the majority of cases, homogeneity of variances was achieved for the laboratories with three repetitions and as a consequence, it was chosen to use the conservative Bonferroni test (assuming homogeneous variances). This as a compromise between the Tukey HSD (homogeneous variances) and Dunnett T3 (non-homogeneous variances) (Fig. 3) to account for the variance uncertainty in case of only two repetitions. It could be concluded for the mortar specimens that besides the trowelled surface (top side), also the bottom side had in a majority of cases a significantly different carbonation depth compared to the other sides (trowelled surface, side 1 and/or side 2), specifically in case of CEM II and CEM III. In case of concrete specimens, this conclusion does not hold. Nevertheless, to maintain continuity in data handling, both bottom and trowelled surfaces were excluded for further statistical analysis on results of both mortar and concrete. Table 4 reports on the percentage of cases (individual laboratories applying a specific accelerated carbonation method) where a statistically significant difference was observed between (1) the bottom side and at least one of the other sides (trowelled side, side 1 or side 2), (2) the bottom side and all other sides (trowelled side, side 1 and side 2), (3) the trowelled side and at least one of the sides (side 1 or side 2) and (4) side 1 and side 2.

3.3.3 Data input for statistical analysis

The following methodology was applied to obtain an input for the statistical analysis comparing the different cement types and standards. All laboratories reported on n measurements for each of the four measured sides of the specimen and q repetitions for each exposure period. Based on Sect. 3.3.2, carbonation depths of the trowelled and bottom surface were excluded. For each of the remaining two sides and after 91 days of exposure (Sect. 3.3.1), a mean depth was calculated based on the n measurements and served as a direct input for statistical analysis (= q * 2 values for each laboratory and test regime) resulting in 719 cases with 25 variables (Online Resource 6). This methodology implies two issues that should be overcome:

-

1.

complete carbonation of the specimens before 91 days was tackled by calculating the theoretical carbonation depth at 91 days exposure based on the slope of the linear regression (as a function of square root of time) and taking the mean depth for each side and for each repetition at 28 or 56 days (depending on availability of data) as a starting point (Online Resource 5). This situation only appeared in 8 out of 116 test regimes.

-

2.

the number of repetitions (2 or 3) is not the same for all laboratories resulting in an unbalanced dataset for statistical analysis. This problem could be tackled by more extensive averaging of the results. However, this extensive averaging would also imply a more undiversified dataset with important changes in variances which might cover up some relevant characteristics of the ILT.

It is also worth mentioning that rounding of numbers was not applied during data processing, however in some cases, individual laboratories already reported rounded values for each measurement according to the applied standard.

3.4 Statistical methodology

The statistical methodology applied in the different subsections is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Beside the ANOVA analysis [44,45,46,47], for the accelerated carbonation test methods where at least three laboratories participated, also ISO 5725-2 [48] was applied to determine the repeatability and reproducibility of a standard measurement method. This standard also provides methods to identify extreme values which can be subdivided into stragglers with extreme values detected between the 95% and 99% confidence levels and outliers with extreme values at more than 99% confidence level both within and between laboratories.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Fresh and hardened properties of mortar and concrete

Analysis of the fresh and hardened properties of mortar and concrete was performed as a quality check of the produced specimens. Deviating results imply warnings for further analysis of the carbonation depth for those specific laboratories. Only the results of laboratories using the cements distributed by HeidelbergCement AG Germany (within Europe) were considered. The number of replicate test results was different for the participating laboratories and therefore it was chosen to average test results for each parameter and laboratory resulting in a balanced dataset. A box-and-whisker plot (inclusive median) was generated and outliers smaller and greater than 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR) were visualised (Online Resource 7). Table 5 summarises for every analysed parameter the mean and standard deviation. If outliers were detected for specific parameters and laboratories, the letters of the laboratories are listed. Furthermore, it is indicated in Table 5 whether a significant difference was observed between the fresh or hardened properties of the mixes prepared with different cements. In this analysis, outliers were excluded. The mean value for each property and for each laboratory was calculated resulting in a single value per laboratory and therefore a balanced series for each cement type. However, not every laboratory performed tests on each cement type leading to an unbalanced data set for comparison between cement types. For mortar, normality of the unstandardized residuals was achieved for all groups, whereas homogeneity of variances was not met in case of air content (p = 0.000) and flexural strength measured after 28 days (p = 0.002). Consequently a post-hoc Dunnett T3 test was performed for these parameters and a significant difference between CEM II and both CEM I and CEM III could be observed for the measurement of the air content. For all other parameters, no significant difference was observed between the different cement types based on a post-hoc Hochberg’s GT2 test. In case of concrete, normality of the unstandardized residuals and homogeneity of variances was achieved for all groups. In contrast with mortar specimens, no significant differences could be found between cement types for the properties mentioned in Table 5 based on a post-hoc Hochberg’s GT2 test.

4.2 Resistance to carbonation – statistical analysis

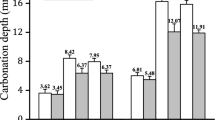

Figures 4 and 5 summarise the mean carbonation depths after 91 days of accelerated carbonation for mortar and concrete, respectively (calculated as described in Sect. 3.3.3). The box-and-whisker plots group the results of the laboratories performing the same accelerated carbonation method for each cement type.

Statistical analysis was performed on two levels. First, the impact of the considered parameters, e.g. cement type, curing type or duration, was checked on laboratory level. Second, in case of sufficient participating laboratories, results obtained from different laboratories applying the same method were grouped to examine the impact of the considered parameters. In the latter case, outliers exceeding 1.5 times the IQR were excluded from the groups (Lab K for CEM I mortar, lab R for CEM II mortar and Lab R for CEM I concrete). For several methods, a very limited number of laboratories provided results leading to limited cases within a group which consequently has an important influence on the results of the performed ANOVA tests.

The box- and whisker plots only allows to assess the between-laboratory variability based on a comparison of means. The Grubb’s test outlined in ISO 5725-2 [48] has the same objective, however, appeared to have less power. Only one of the three outliers (Mortar—CEM I—lab K) has been confirmed by this test. Also, it is important to assess the within-laboratory variability based on a comparison of the variance of each laboratory applying a specific standard for a certain cement type (CEM I, CEM II or CEM III) and specimen type (mortar or concrete). This analysis is based on the Cochran’s test described by ISO 5725-2 [48] and could be applied on the carbonation depth results of five accelerated carbonation methods, namely: (1) predefined sealed curing and carbonation at 1% CO2, (2) EN 13295 and (3) EN 12390–12 on mortar scale and (4) predefined sealed curing and carbonation at 1% CO2 and (v) EN 13295 on concrete scale. On concrete scale, no stragglers or outliers for the within laboratory variability were observed, whereas on mortar scale, stragglers and outliers for the within laboratory variability were detected for six laboratories (Online Resource 8).

A summary of the determination of repeatability (within-laboratory variance) and reproducibility (within- and between-laboratory variance) of the five accelerated carbonation test methods with at least three participating laboratories is given in Table 6. Both the coefficient of variation (COV) of repeatability and reproducibility, respectively, are in the same order of magnitude for the different cement types and standards and the COVreproducibility is generally up to 3 times larger than the COVrepeatability. Except for EN 12390-12 on mortar scale where a significantly higher COVreproducibility was calculated and which is also not in accordance with the expected variability reported in CEN/TR 17172 [49]. This high COV can be explained by one of the three laboratories that applied a considerably different curing method compared to the prescriptions from the standard (14 days sealed curing instead of 28 days water curing) and another laboratory had to interrupt the accelerated carbonation tests during 1 month as a consequence of COVID-19 lockdown. For both sealed curing (predefined curing and carbonation at 1% CO2) and water curing (EN 13295), mostly a decrease of the COV from CEM I to CEM II and CEM III was observed (Online Resource 9).

The outlier detection from Sect. 4.1 based on the fresh and hardened properties of mortar and concrete and summarised in Table 5 did not relate with the outliers based on the carbonation depth measurements from Figs. 4 and 5. Consequently, it seems that a deviating carbonation depth result for a specific accelerated carbonation method executed by a specific laboratory is not caused by deviating properties of fresh and hardened concrete. However, also some outliers from Table 5 are related to an accelerated carbonation method in which only one laboratory participated. Therefore, it is impossible to conclude on a possible deviating carbonation depth result as a consequence of deviating fresh or hardened properties (lab M).

4.2.1 Impact of cement type

The mean 91-day carbonation depths of CEM I, CEM II and CEM III based mortar and concrete were analysed in two steps. First, the ranking of the cements with regard to the carbonation depth was determined for each of the considered laboratories and carbonation tests. In the majority of the cases, the ranking is CEM I < CEM II < CEM III. Tables 7 and 8 indicate the ranking in non-bold text in case CEM I < CEM II < CEM III as opposed to bold in case the ranking switched in comparison to the general observation. Second, it was assessed whether the differences in carbonation depth between CEM I, CEM II and CEM III based mortar or concrete could be considered significant (non-bold) or not (bold). For the mortars that underwent the predefined curing procedure prior to preconditioning and exposure to elevated CO2 concentrations, 2 out of 7 laboratories that performed a carbonation test at 1% CO2 observed a ranking that deviated from CEM I < CEM II < CEM III (Table 7). In those cases, the CEM II based mortar was characterized by a lower carbonation depth than the CEM I based mortar. Nonetheless, the differences in carbonation depth between CEM I and CEM II based mortar were found to be non-significant. The same statement holds true for just one laboratory that conducted the accelerated carbonation experiment at 3% CO2. The observation of having non-significant differences in carbonation depth between at least two binder systems seemed to have occurred more often for carbonation tests conducted at the lower range CO2 levels (1% CO2: 5 out of 7 laboratories; 2% CO2: 1 out of 2 laboratories versus 3% CO2: 1 out of 4 laboratories; 4% CO2: 0 out of 3 laboratories). Similar conclusions could be drawn for the mortars subjected to accelerated carbonation tests of which the curing was as prescribed by the considered standards.

When CO2 levels were 3% or more, more uniform findings in terms of carbonation depth ranking and significant differences in carbonation depth, were reported. On the concrete level, the same goes for accelerated carbonation testing after predefined curing. On the other hand, accelerated carbonation at 1% CO2 conforming to EN 13295 resulted in a better compliance with the general CEM I < CEM II < CEM III ranking and significant differences in carbonation depth between them. For the standards involving exposure to higher CO2 levels this uniformity is somewhat lost. It should be noted that the number of participating laboratories for each accelerated carbonation method varied considerably. For instance, predefined curing followed by carbonation testing at 1% CO2 as well as carbonation testing at 1% CO2 in accordance with EN 13295 were the most frequent adopted test procedures among the participating laboratories, especially for mortar. Perhaps the larger field of participants there revealed better to what extent test results could vary. Therefore, the now seemingly more uniform findings for the test methods with a much lower field of participants should still be interpreted with caution. It could very well be that these test methods are more robust. Yet, this should preferably be verified by extending the interlaboratory evaluation for these methods.

After the evaluation per individual laboratory, a more clustered approach was adopted where all data were first grouped per test method and then subjected to an overall statistical analysis (Table 8). In the majority of the applied carbonation methods, the ranking of the 91-day carbonation depths remained CEM I < CEM II < CEM III, meaning that CEM I has the highest resistance to carbonation and CEM III the lowest. Only in 3 out of the 22 methods, ranking was found to be CEM II < CEM I < CEM III. This was the case on mortar scale for the predefined curing method with carbonation testing at 1% CO2 and the variant to EN 13295 as well as on concrete scale for the fib method. A significant difference in carbonation depth between the cement types was found for methods EN 13295, LNEC E391, BSI 1881-210 and GB/T50082 on mortar scale and predefined curing at 3% and 4%, EN13295 and EN 12390-12 on concrete scale.

In 10 out of the 22 methods adopted in this study, a non-significant difference between CEM I and CEM II was observed. Only for five accelerated carbonation methods (predefined curing + 3% CO2 and EN 12390-12 for mortar and predefined curing + 1% & 2% CO2 as well as LNEC E391 for concrete), the non-significant difference was related to CEM II and CEM III. In general, it can be concluded that the considered (inter)national standards are able to rank different cement types in the same way. When ranking was not according to the general observed order CEM I < CEM II < CEM III and was CEM II < CEM I (< CEM III) instead, there was no significant difference between the carbonation depth after 91 days of accelerated carbonation of CEM I and CEM II.

4.2.2 Impact of curing

Similar to the cement type assessment, the effect of the applied curing method was in a first stage analysed per individual laboratory (Table 9). The mean 91-day carbonation depths obtained for the predefined curing method and correspondingly applied standard curing method were ranked in descending order. Furthermore, it was statistically verified whether the observed differences in carbonation depth were significant or not (with Predefined > standard curing and significant differences in non-bold text ; Standard > Predefined curing and non-significant differences in bold text).

On the mortar level, the predefined curing method (1% CO2) (28 days sealed curing) tends to result in higher carbonation depths than curing in compliance with EN 13295 (28 days underwater), and the differences in the carbonation depth are often significant. Regardless of two exceptions, the observed ranking was consistent for all three cement types. Nonetheless, differences in carbonation depth between curing methods are mainly significant for CEM I based mortar (6 out of 7 laboratories). For CEM II and especially CEM III based mortar, laboratories more often reported non-significant differences (2 out of 6 laboratories and 4 out of 6 laboratories for CEM II and CEM III, respectively).

The ranking seems to be highly dependent on the duration of water curing. Three laboratories applied only 3 days of water curing (Variant to EN 13295 and SIA 262/1) as opposed to the common 28 days, and reported higher mean carbonation depths relative to those obtained after 28 days of predefined sealed curing. More or less similar behaviour was observed when fib curing and even LNEC E391 were taken as the standard curing method. These methods involve 7 and 14 days of water curing, respectively, which is more than double the duration of the Variant to EN 13295. For LNEC E391, differences are mostly not significant on both mortar and concrete scale. Here 14 days water curing in combination with 14 days preconditioning in laboratory air environment resulted in similar carbonation depths as 28 days sealed curing followed by 28 days preconditioning in laboratory air environment. Curing in accordance to EN 12390-12 (28 days underwater or at ≥ 95% RH) shows a more biased carbonation ranking relative to predefined sealed curing with differences often being non-significant. It is important to remark that lab H deviated considerably from the standard by applying 14 days sealed curing instead of the 28 days water curing which can explain the inconsistent ranking compared to the other laboratories. It remains difficult to attribute the change in carbonation depth ranking to the applied duration of optimal curing solely since sample preconditioning also varies between carbonation test methods.

When looking at the results for concrete, comparison of the 91-day carbonation depths for 28 days of predefined sealed curing and 28 days water curing cf. EN 13295 usually gives the same carbonation depth ranking as for mortar (Predefined > EN 13295). Similar to the mortar results, shortening the water curing period to only 3 days changes this ranking (Variant to EN 13295 > Predefined). Differences in outcome between the two methods appear to be non-significant though. For fib curing relative to predefined curing it was not possible to draw solid conclusions due to lack of sufficient data to adequately assess homogeneity of variances and significant differences in carbonation depth between both methods. In comparison with mortar, the ranking predefined vs. EN 12390-12 for concrete seems to be more consistent and in favour of predefined > EN 12390-12 with significant differences in carbonation depth between the two methods for CEM I and CEM II based concrete. Nonetheless, one should remain cautious with generalizing this conclusion since it was derived from results reported by only one laboratory. The same remark can be made for LNEC E391 and SIA 262/1 curing relative to predefined curing, with also just one participating laboratory for each set of curing procedures. With only 3 days of water curing, the SIA 262/1 method yields higher carbonation depths than predefined curing, but then mainly for blended cement concrete (CEM II and CEM III). This is in line with the mortar results, be it that differences in carbonation depth are less consistently significant for concrete.

The impact of curing type can also be investigated by comparing the clustered results of specimens which followed the predefined curing method and the ones which followed the curing method as mentioned in the considered standards. As shown in Table 9 already, a large group of participants applied standard EN 13295 which allowed to make a distinction in carbonation resistance between 28 days water cured (curing as defined in EN 13295) and 28 days sealed cured (predefined curing) specimens and followed by the same preconditioning conditions. Normal distribution of the data was confirmed for each group, except for CEM I and CEM II mortar. Based on the histograms of the unstandardized residuals, normal distribution was assumed for all groups. Also homogeneity of variances was checked where only in case of mortar specimens belonging to the CEM I group, homogeneity of variances was not achieved. The one-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference between water and sealed curing for each cement type and specimen type (mortar or concrete). It can therefore be concluded that sealed curing resulted in an average increased carbonation depth of 67%, 17% and 16% compared to water curing for CEM I, CEM II and CEM III mortar, respectively, and 60%, 53% and 19% for CEM I, CEM II and CEM III concrete, respectively. This increase in carbonation depth and consequently the impact of the curing type on the resistance to carbonation is larger in case of CEM I compared to CEM III, while for CEM II, the extent of the impact of the curing method seems also to depend on the specimen type. This is in line with the higher amount of significant differences observed in Table 9 for CEM I compared to CEM II and CEM III mortar when looking at the comparison between the predefined curing and EN 13295. This observation was rather unexpected and cannot be explained by the test results obtained from this ILT.

A second aspect that can be further analysed from the clustered data is the curing duration. First, EN 13295 will be compared with the results obtained based on a variant of EN 13295 in which underwater curing was reduced from 28 to 3 days and preconditioning in the climate chamber was reduced from 28 to 21 days. This dataset posed some difficulties related to the assumptions to perform an ANOVA. In none of the groups, homogeneity of variances is observed. Also, normality of unstandardized residuals is only observed in case of CEM I mortar and concrete thus not in case of CEM II. Nevertheless, the one-way ANOVA showed a significant difference between the two curing durations for both CEM I and CEM II mortar and concrete specimens. The mean carbonation depth after 91 days of accelerated carbonation raised with 124% and 123% for CEM I specimens in case of mortar and concrete, respectively, when curing duration was reduced to 3 days. This increase was only 65% and 73% for CEM II specimens. These findings confirm the previous assumption that CEM I is more prone to carbonation depth changes as a function of the curing method compared to CEM II mixtures. A more detailed study regarding the saturation state and microstructure after curing and preconditioning in combination with the changes in phase and pore assemblage, porosity and saturation level due to carbonation is advisable.

Secondly, BSI 1881-210, LNEC E391 and SIA 262/1 apply approximately the same carbonation conditions (4 vol% CO2, 20 °C and 50–57% RH) while the underwater curing period is 28, 14 and 3 days and the preconditioning period 14 days laboratory climate for both BSI 1881-210 and LNEC E391 and 25 days at 20 °C and 57% RH for SIA 262/1. Given the similarities, it makes sense to mutually compare these three methods. The summary of this analysis is given in Table 10. Normality of the unstandardized residuals could be found in the majority of the cases except for CEM I and CEM III mortar and homogeneity of variances was only found in case of CEM II mortar and CEM I and CEM III concrete. A post-hoc Dunnett T3 and Tukey HSD test for CEM I and CEM II mortar, respectively, showed a significant difference for the three considered methods. Furthermore, a one-way ANOVA (in case of homogeneity of variances) and a Welch ANOVA (in case of non-homogeneous variances) showed a significant difference between LNEC E391 and SIA 262/1 for CEM II concrete. However, for CEM III mortar and CEM I and CEM III concrete, no significant difference was found between the two methods. When comparing BSI 1881-210, LNEC E391 and SIA 262/1 for each considered cement type and considering the underwater curing period as the most decisive parameter for the degree of cement hydration, formation of the microstructure and consequently the resistance to carbonation, it can be concluded that in case of mortar, lowering the curing period results in significantly deeper carbonation depths. For CEM I, a stepwise average increase of 50% and 191% was observed when lowering the duration from 28 (BSI 1881-210) to 14 days (LNEC E391) and further on to 3 days (SIA 262/1), respectively. In case of CEM II, this increase was 134% and 61%. On the contrary, the carbonation depth in concrete was reduced when curing duration was lowered from 14 days (LNEC E391) to 3 days (SIA 262/1). It should be noted that each of the tests was executed by only one laboratory (lab M and lab H for respectively LNEC E391 and SIA 262/1) and results may not be generalised.

4.2.3 Impact of CO2 concentration

The impact of the CO2 concentration on the resistance to carbonation was checked based on the predefined curing method and carbonation at 1%, 2%, 3% and 4%. However, it needs to be noted that the relative humidity during preconditioning and carbonation varies between 50 and 65% or preconditioning was executed under uncontrolled laboratory conditions. Temperature was in all situations approx. 20–21 °C or uncontrolled laboratory conditions. No clear conclusion could be drawn as also expected based on the box-and-whisker plots from Figs. 4 and 5. The significant differences were rather at random and no general conclusions regarding cement type or specimen type (mortar or concrete) could be drawn. Consequently, the reproducibility variation between laboratories seems to be larger compared to the effect of raising the CO2 concentration from 1 to 4%. Even in case of the very high CO2 concentration applied in the standard GB/T50082, i.e. 20%, CEM I mortar showed lower carbonation depths compared to all other methods. It is unlikely that 70% RH during preconditioning and carbonation causes this increased resistance to carbonation. Only in case of CEM III mortar, the carbonation depth is larger compared to all other methods.

4.2.4 Impact of aggregates

Comparison of the 91-day carbonation depths of mortar and concrete per individual laboratory for a given carbonation method and cement type shows that the most often observed ranking is mortar < concrete (Table 11, in 34 out of 45 individual cases). In 6 cases this ranking represented non-significant differences in carbonation depth. Within the 11 cases in which the opposite ranking was observed, 5 of them show significant differences in carbonation depth. No specific causes could be identified for the deviating cases. They could not be assigned to a specific curing method, subsequent preconditioning and CO2 exposure conditions (Table 4) nor the cement type used in the mortar and concrete. In Table 11, the most frequently occurring ranking (mortar < concrete) and significantly different carbonation depths are indicated in non-bold text as opposed to bold text. This ranking (mortar < concrete) can be explained by two key characteristics affecting the carbonation behaviour [1]: (1) the lower CO2 buffering capacity due to a lower paste content of concrete compared to mortar and (2) the additional porosity that is introduced by the aggregates in the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) of concrete and that is facilitating more easy CO2 ingress along the ITZ pathways. However, it remains difficult to strongly conclude this, since the mortar compositions were not entirely representative for the concrete compositions. No corrections were made in the mix design to account for differences between mortar and concrete in terms of water absorption and specific surface area of the aggregates.

This is a critical issue, as for practical considerations, carbonation testing is often executed on mortar scale and then assumed to be representative for the concrete scale. Within the framework of this interlaboratory test, this issue could also be tackled using the clustered approach where the data per accelerated test method are grouped. Figure 6 shows the relation between the carbonation coefficient on mortar and concrete scale for each applied method. The error bars represent the standard deviation for each method as a result of the various laboratories performing the same accelerated carbonation test. A linear regression through all data points was forced trough zero and showed that the carbonation coefficient of concrete was 1.18 times the one of mortar (R2 = 0.728). This agrees with the findings of Papadakis et al. [50] where a factor of 1.1 was found between mortar and concrete scale when the aggregate to cement ratio (a/c) was increased by a factor of 1.7. The a/c factor in the ILT increased on average 1.79 times when upscaling from mortar to concrete.

5 Conclusion

This extensive interlaboratory test campaign reports some important findings on various accelerated carbonation test methods as well as on the resistance of mortar and concrete to carbonation for Portland cement and blended cements, more specifically CEM I 42.5 N, CEM II/B-V 42.5 N and CEM III/B 42.5 N. Seventeen laboratories provided accelerated carbonation depth results and in total twenty two laboratories participated within the framework of this ILT. In this way it was possible to compare a predefined curing as a reference method with seven different national and international test methods supplemented by two variants on two specific international tests for accelerated carbonation performed on both mortar and concrete scale. However, also important difficulties were recognised as a result of (1) unforeseen restrictions related to the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic and (2) unexpected variability within and between laboratories or a limited number of laboratories applying a specific standard which makes generalisation of conclusions not always evident. Nevertheless, the predetermined research questions could be analysed and the following conclusions can be drawn:

-

Widely adopted standards and recommendations, followed in this study, to measure carbonation depth are able to rank different cement types similarly. When ranking is not according to the generally observed order CEM I < CEM II < CEM III and is CEM II < CEM I (< CEM III) instead, there is mostly no significant difference between the carbonation depth after 91 days of accelerated carbonation of CEM I and CEM II.

-

In general, predefined sealed curing for 28 days at 20 °C results in larger carbonation depths compared to the depths obtained from other curing methods imposed by the investigated test methods. However, when water curing is reduced from 28 to 3 or 7 days, this results in higher carbonation depths for those accelerated test methods compared to the reference test method. Nevertheless, it remains difficult to attribute the change in carbonation depth to the applied duration of curing alone since sample preconditioning also varies between carbonation test methods.

-

The increase in carbonation depth and consequently the impact of the curing method on the resistance to carbonation is larger in case of CEM I compared to CEM III, while for CEM II, the extent of the impact of the curing method also seems to depend on the specimen type (mortar/concrete).

-

The existence of significant differences between CO2 concentrations is rather random and no general conclusions could be drawn for all cement types and specimen types. It seems that the reproducibility variation between laboratories is larger compared to the effect of raising the CO2 concentration from 1 to 4%.

-

Based on all carbonation depth measurements, the carbonation coefficient of concrete is 1.18 times the carbonation coefficient of mortar. The aggregate to cement factor increased in this study on average 1.79 times when upscaling from mortar to concrete.

-

The calculated COV of repeatability and reproducibility are rather high (COVrepeatability = 5.5–15.9% and COVreproducibility = 14.3–67.7%); however, within acceptable ranges for this type of ILT where specimens were made by each of the laboratories themselves.

Also some other observations and conclusions are worth mentioning:

-

No direct relation between outlying results of the fresh and hardened properties and outlying results of the resistance to carbonation could be found.

-

Carbonation rates based on the carbonation depth measured after 91 days exposure show the best agreement with the slope of the linear regression (taking into account data points at 0, 14, 28, 56 and 91 days of CO2 exposure) and therefore serve as the better estimate for the potential resistance to carbonation compared to evaluating results derived from an exposure of 14, 28 or 56 days.

-

In particular for CEM I specimens, no clear colour change boundary could be observed after the restricted 1 h ± 15 min between spraying a fine mist of the pH indicator and the time of reading the colour change boundary. It is assumed that leaching of alkaline pore solution causes the blurry colour change boundary.

Another objective of working group 1 and 2 of RILEM TC 281-CCC is studying the effect of SCMs on natural carbonation and the correlation between atmospheric carbonation and accelerated carbonation. Simultaneously with the start of the accelerated carbonation tests, reported in this paper, also natural carbonation tests on the same mix designs were launched. It is the objective of the RILEM TC 281-CCC to report on these results in a follow-up paper. This will then allow us to make correlations between accelerated and natural carbonation, and propose recommendations for optimized accelerated carbonation testing representative for the natural resistance to carbonation of mortar and concrete with SCMs.

References

von Greve-Dierfeld S et al (2020) Understanding the carbonation of concrete with supplementary cementitious materials: a critical review by RILEM TC 281-CCC. Mater Struct 53(6):136. https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-020-01558-w

Leemann A, Nygaard P, Kaufmann J, Loser R (2015) Relation between carbonation resistance, mix design and exposure of mortar and concrete. Cem Concr Compos 62:33–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2015.04.020

Bernal S, Provis J, Brice DG, Kilcullen A, Duxson P, Van Deventer J (2012) Accelerated carbonation testing of alkali-activated binders significantly underestimate the real service life: The role of the pore solution. Cem Concr Res 42:1317–1326

Leemann A, Pahlke H, Loser R, Winnefeld F (2018) Carbonation resistance of mortar produced with alternative cements. Mater Struct 51(5):114. https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-018-1239-3

Qiu Q (2020) A state-of-the-art review on the carbonation process in cementitious materials: fundamentals and characterization techniques. Constr Build Mater 247:118503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118503

Ashraf W (2016) Carbonation of cement-based materials: challenges and opportunities. Constr Build Mater 120:558–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.05.080

Šavija B, Luković M (2016) Carbonation of cement paste: understanding, challenges, and opportunities. Constr Build Mater 117:285–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.04.138

Sevelsted TF, Skibsted J (2015) Carbonation of C–S–H and C–A–S–H samples studied by 13C, 27Al and 29Si MAS NMR spectroscopy. Cem Concr Res 71:56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CEMCONRES.2015.01.019

Steiner S, Lothenbach B, Proske T, Borgschulte A, Winnefeld F (2020) Effect of relative humidity on the carbonation rate of portlandite, calcium silicate hydrates and ettringite. Cem Concr Res 135:106116. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CEMCONRES.2020.106116

Castellote M, Fernandez L, Andrade C, Alonso C (2009) Chemical changes and phase analysis of OPC pastes carbonated at different CO2 concentrations. Mater Struct 42(4):515–525. https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-008-9399-1

Hyvert N, Sellier A, Duprat F, Rougeau P, Francisco P (2010) Dependency of C–S–H carbonation rate on CO2 pressure to explain transition from accelerated tests to natural carbonation. Cem Concr Res 40(11):1582–1589. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CEMCONRES.2010.06.010

Auroy M et al (2018) Comparison between natural and accelerated carbonation (3% CO2): impact on mineralogy, microstructure, water retention and cracking. Cem Concr Res 109(April):64–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2018.04.012

Thiery M, Villain G, Dangla P, Platret G (2007) Investigation of the carbonation front shape on cementitious materials: effects of the chemical kinetics. Cem Concr Res 37(7):1047–1058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2007.04.002

Cizer Ö, Rodriguez-Navarro C, Ruiz-Agudo E, Elsen J, Van Gemert D, Van Balen K (2012) Phase and morphology evolution of calcium carbonate precipitated by carbonation of hydrated lime. J Mater Sci 47(16):6151–6165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-012-6535-7

Black L, Breen C, Yarwood J, Garbev K, Stemmermann P, Gasharova B (2007) Structural features of C–S–H(I) and its carbonation in air—a Raman spectroscopic study. Part II: carbonated phases. J Am Ceram Soc 90(3):908–917. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1551-2916.2006.01429.x

Saetta AV, Vitaliani RV (2004) Experimental investigation and numerical modeling of carbonation process in reinforced concrete structures: Part I: theoretical formulation. Cem Concr Res 34(4):571–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CEMCONRES.2003.09.009

Phung QT, Varzina A, Perko J, Jacques D, Maes N, Cizer O (2020) On the effects of relative humidity and CO2 concentration on carbonation of cement pastes

Drouet E, Poyet S, Le Bescop P, Torrenti JM, Bourbon X (2019) Carbonation of hardened cement pastes: influence of temperature. Cem Concr Res 115:445–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CEMCONRES.2018.09.019

Galan I, Andrade C, Castellote M (2013) Natural and accelerated CO2 binding kinetics in cement paste at different relative humidities. Cem Concr Res 49:21–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CEMCONRES.2013.03.009

Saillio M, Baroghel-Bouny V, Pradelle S, Bertin M, Vincent J, d’Espinose de Lacaillerie JB (2021) Effect of supplementary cementitious materials on carbonation of cement pastes. Cem Concr Res 142:106358. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CEMCONRES.2021.106358

Lothenbach B, Scrivener K, Hooton RD (2011) Supplementary cementitious materials. Cem Concr Res 41(12):1244–1256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2010.12.001

De Belie N, Soutsos M, Gruyaert E (2018) Properties of fresh and hardened concrete containing supplementary cementitious materials, vol 25. Springer, Cham

EN 196-2 (2013) Method of testing cement—part 2: chemical analysis of cement

EN 196-6 (2019) Methods of testing cement—part 6: determination of fineness

EN 196-1 (2016) Methods of testing cement—part 1: determination of strength

EN 206:2013+A2 (2021) Concrete—specification, performance, production and conformity

EN 1015-3 (1999) Methods of test for mortar for masonry—part 3: determination of consistence of fresh mortar (by flow table)

EN 1015-7 (1998) Methods of test for mortar for masonry—part 7: determination of air content of fresh mortar

DIN 1045-2 (2008) Concrete, reinforced and prestressed concrete structures—part 2: concrete—specification, performance, production and conformity—application rusels for DIN EN 206-1

EN 1097-6 (2013) Tests for mechanical and physical properties of aggregates—part 6: determination of particle density and water absorption

EN 12390-2 (2019) Testing hardened concrete—part 2: making and curing specimens for strength tests

EN 12350-2 (2019) Testing fresh concrete—part 2: slump test

EN 12350-6 (2019) Testing fresh concrete—part 6: density

EN 12350-7 (2019) Testing fresh concrete—part 7: air content—pressure methods

EN 12350-1 (2019) Testing fresh concrete—part 1: sampling and common apparatus

EN 12390-3 (2019) Testing hardened concrete—part 3: compressive strength of test specimens

EN 13295 (2004) Products and systems for the protection and repair of concrete structures—test methods—determination of resistance to carbonation

Fib Bulletin 34, Model code for service life design (2006)

EN 12390-12 (2020) Testing hardened concrete—part 12: determination of the carbonation resistance of concrete—accelerated carbonation method

BSI-BS 1881-210, Testing hardened concrete—part 210: determination of the potential carbonation resistance of concrete—accelerated carbonation method. BSI

SIA 262/1 (2019) Betonbau - Ergänzende Festlegungen

LNEC E391 (1993) Betões - Determinação da resistència à carbonatação

GB/T 50082 (2009) Standard for test methods of long-term performance and durability of ordinary concrete

Cardinal RN, Aitken MRF (2006) ANOVA for the behavioural sciences researcher. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers

Myers RH, Myers SL, Walpole RE, Ye K (2006) Probability and statistics for engineers and scientists, 8th Intern. Pearson Education

Johnson RA, Miller I, Freund JE (2010) Probability and statistics for engineers, 8th edn. Pearson Education

Mendenhall W, Sincich T (2007) Statistics for engineering and the sciences, 5th edn. Pearson Education

ISO 5725-2, Accuracy (trueness and precision) of measurement methods and results—part 2: basic method for the determination of repeatability and reproducibility of a standard measurement method

CEN/TR 17172 (2018) Validation testing program on chloride penetration and carbonation standardized test methods

Papadakis V, Vayenas C, Fardis M (1991) Funadamental Modeling and experimental investigation of concrete carbonation. ACI Mater J 88(4):363–373

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank HeidelbergCement AG for the supplied cements and the chemical and physical analysis. H. Vanoutrive has received internal funding from KU Leuven which made this interlaboratory study possible. P. Van den Heede, N. Alderete and Z. Liu are funded by the Research Foundation—Flanders (FWO) (project No. G062720N, 12ZG820N and G0F3619N). The financial support of FWO is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This report has been prepared by members of the working groups 1 and 2 within a framework of RILEM TC 281-CCC “Carbonation of concrete with supplementary cementitious materials” and further reviewed and approved by all members of the RILEM TC 281-CCC.

TC Membership Chair: Prof. Nele De Belie. Deputy Chair: Prof. Susan Bernal Lopez. Members: Natalia Alderete, Carmen Andrade, Ueli Angst, Tushar Bansal, Véronique Baroghel-Bouny, Muhammed P.a. Basheer, Nele De Belie, Susan Bernal Lopez, Hans D. Beushausen, Leon Black, Aires Camões, Servando Chinchón-Payá, Özlem Cizer, Gisela Paola Cordoba, Martin Cyr, Patrick Dangla, Yuvaraj Dhandapani, Katja Dombrowski-Daube, Vilma Ducman, Yogarajah Elakneswaran, Jan Elsen, Juan Manuel Etcheverry, Miren Etxeberria, Ana Maria Fernandez-Jimenez, Lander Frederickx, Isabel Fuencisla Saez del Bosque, Cassandre Le Galliard, Inès Garcia Lodeiro, Daniel Geddes, Christoph Gehlen, Mette Geiker, Guoqing Geng, Bahman Ghiassi, Gregor Gluth, Cyrill Grengg, Elke Gruyaert, R. Doug Hooton, Bruno Huet, Andres Idiart, Ivan Ignjatović, Kei-Ichi Imamoto, Shiju Joseph, Siham Kamali-Bernard, Antonis Kanellopoulos, Xinyuan Ke, Sylvia Kessler, Heejeong Kim, Arto Köliö, Juan Li, Ning Li, Tung Chai Ling, Qing-Feng Liu, Zhiyuan Liu, Barabare Lothenbach, Isabel Martins, José-Fernando Martirena-Hernandez, César Medina Martinez, Fabrizio Moro, Shishir Mundra, Marija Nedeljkovic, Kolawole A. Olonade, José Pacheco, Christian Paglia, Angel Paloma, Ravi Patel, Janez Perko, Quoc Tri Phung, John L. Provis, Francisca Puertas, Nuria Rebolledo, Marlene Sakoparnig, Javier Sancez Montero, Francesco Santoro, Sriram Pradeep Saridhe, Karen Scrivener, Marijana Serdar, Zhenguo Shi, Kosmas K. Sideris, Ruben Snellings, Matteo Stefanoni, Charlotte Thiel, Karl-Christian Thienel, Michael D.A. Thomas, Ilda Tole, Luca Valentini, Philip Van den Heede, Hanne Vanoutrive, Yury Andrés Villagran Zaccardi, Talakokula Visalakshi, Anya Vollpracht, Stefanie Von Greve-Dierfeld, Brant Walkley, Fazhou Wang, Ling Wang, Jinxin Wei, Lia Weiler, Bei Wu, Yan Yao, Guang Ye, Maciej Zając, Zengfeng Zhao, Semion Zhutovsky.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vanoutrive, H., Van den Heede, P., Alderete, N. et al. Report of RILEM TC 281-CCC: outcomes of a round robin on the resistance to accelerated carbonation of Portland, Portland-fly ash and blast-furnace blended cements. Mater Struct 55, 99 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-022-01927-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-022-01927-7