Abstract

Objective

To explore the correlation between periodontal health and cognitive impairment in the older population to provide the evidence for preventing cognitive impairment from the perspective of oral health care in older adults.

Methods

A comprehensive search was conducted in PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, the Web of Science, the China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang Data, the China Science and Technology Journal Database, and the China Biomedical Literature Database, to include both cross-sectional and longitudinal cohort studies on the association between periodontal health and cognitive impairment in older adults. The search was completed in April 2023. Following quality assessment and data organization of the included studies, meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.4.

Results

Twenty-two studies involving a total of 4,246,608 patients were included to comprehensively assess periodontal health from four dimensions (periodontitis, tooth loss, occlusal support, and masticatory ability), with the outcome variable of cognitive impairment (including mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease and all-cause dementia). Meta-analysis showed that, compared to those of periodontally healthy older adults, the risk of cognitive impairment in older adults with poor periodontal health, after adjusting for confounders, was significantly greater for those with periodontitis (OR=1.45, 95% CI: 1.20–1.76, P<0.001), tooth loss (OR=1.80, 95% CI: 1.50–2.15, P<0.001), compromised occlusal support (OR=1.87, 95% CI: 1.29–2.70, P=0.001), and reduced masticatory ability (OR=1.39, 95% CI: 1.11–1.75, P=0.005). The risk of cognitive impairment was higher in older adults with low-dentition than in those with high-dentition. Subgroup analysis revealed older individuals with fewer remaining teeth were at a higher risk of developing cognitive impairment compared to those with more remaining teeth, as shown by the comparison of number of teeth lost (7–17 teeth compared to 0–6 teeth) (OR=1.64, 95% CI: 1.13–2.39, P=0.01), (9–28 teeth compared to 0–8 teeth) (OR=1.13, 95% CI: 1.06–1.20, P<0.001), (19–28 teeth compared to 0–18 teeth) (OR=2.52, 95% CI: 1.32–4.80, P=0.005), and (28 teeth compared to 0–27 teeth) (OR=2.07, 95% CI: 1.54–2.77, P<0.001). In addition, tooth loss in older adults led to a significantly increased risk of mild cognitive impairment (OR=1.66, 95% CI: 1.43–1.91, P<0.001) and all-cause dementia (OR=1.35, 95% CI: 1.11–1.65, P=0.003), although the correlation between tooth loss and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease was not significant (OR=3.89, 95% CI: 0.68–22.31, P=0.13).

Conclusion

Poor periodontal health, assessed across four dimensions (periodontitis, tooth loss, occlusal support, and masticatory ability), represents a significant risk factor for cognitive impairment in older adults. The more missing teeth in older adults, the higher risk of developing cognitive impairment, with edentulous individuals particularly susceptible to cognitive impairment. While a certain degree of increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease was observed, no significant association was found between tooth loss and the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Enhancing periodontal health management and delivering high-quality oral health care services to older adults can help prevent cognitive impairment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Population aging is a global trend in the present era. According to statistics from the 2022 World Health Organization, the number and proportion of older people in all countries worldwide are on the rise. By 2030, one-sixth of the global population will be older than 60 years (1). Toward the middle of this century, the population aged 65 years and older is expected to double (2). The increase in global life expectancy reflects overall improvements in health conditions and highlights the growing demand for healthcare services for older people. Consequently, healthcare professionals need to identify and prevent risk factors associated with the health of older persons, providing high-quality healthcare services to those in need and ultimately enhancing their quality of life.

Cognitive impairment is a syndrome characterized by the core symptom of acquired cognitive function impairment, which can lead to a decline in the patient’s daily life and work capacity, with or without accompanying behavioral abnormalities. Depending on its severity, it is classified into mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia (3). A nationwide cross-sectional study in China reported that the prevalence of MCI among people aged 60 years and older was approximately one of six, while the overall incidence of dementia was approximately one sixteenth (4). Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder and the most common form of dementia. The number of patients with AD in China has reached nearly 10 million (4). These increased numbers of patients place an enormous burden on families, society and the economy. Previous studies have shown that up to 40% of dementia risk can be avoided by altering modifiable risk factors (5). However, oral health is not typically considered among these factors, highlighting the need to investigate the potential link between oral health and dementia risk.

Periodontal health refers to the good condition of the gums, tissues surrounding the teeth, and jawbone in the oral cavity, free from inflammation, infection, or other diseases (6–8). Oral diseases represent a significant global public health issue, with mounting evidence indicating that as age increases, poor oral health becomes more prevalent. As the oral resistance of older people weakens, the susceptibility to periodontal diseases increases (9, 10). The fourth Chinese national oral health epidemiological survey showed that periodontal diseases pose a common threat to oral health in Chinese residents, particularly the population aged 65 to 74 years in China, with only approximately one in eleven people maintaining healthy periodontal status (11). Failure to promptly address early symptoms of periodontal disease can lead to gum health issues, tooth loosening or even loss. This not only impairs oral mastication function and occlusal support but also poses a severe risk to overall health, increasing susceptibility to chronic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases and dementia (12).

Given the significant impact of poor periodontal health on the overall health of older adults, particularly in relation to cognitive function, it is crucial to explore the correlation between periodontal health and cognitive impairment in the older population. Since many cognitive impairments are irreversible, it is necessary to clarify the correlation between periodontal health and cognitive impairment in older people to intervene in the risk factors that cause cognitive impairment, thus delaying or preventing its occurrence. This study intends to conduct a meta-analysis of cross-sectional and longitudinal cohort studies on periodontal health and cognitive impairment to investigate whether periodontal health is an independent risk factor for cognitive impairment in the older population, providing evidence for future preventive measures for cognitive impairment in older adults from the perspective of oral health care.

Methods

Databases and search terms

The literature that study on the correlation between periodontal health and cognitive impairment in the older population was searched in eight databases, PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, the Web of Science, the China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang Data, the China Science and Technology Journal Database and the China Biomedical Literature Database, between the establishment of the databases and April 2023. The following search terms were used: ‘periodontal health’, ‘oral condition’, ‘cognition’, ‘cognitive impairment’, ‘Alzheimer’s disease’, ‘older adults’, and ‘older population’.

Selection and extraction criteria of articles

The inclusion criteria for articles were as follows: (1) study types: preferred longitudinal cohort study otherwise cross-sectional study, (2) study population: individuals aged 60 years or older, (3) studies available: odds ratios (OR), hazard ratios (HR), and relative risk (RR) associated with cognitive impairment, (4) exposure factors: periodontal health-related indicators, such as periodontitis, tooth loss, occlusal support, and masticatory ability, (5) outcome of the study: at least one of following cognitive screening tools were used to assess the cognitive status of the study population, including mini-mental state examination (MMSE), the Korean version of the mini-mental status examination (MMSE-KC), the Japanese version of the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA-J), the modified mini-mental state examination (3MS), and the consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s disease - neuropsychological battery (CERAD-NB). The diagnostic criteria included the Petersen criteria, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th edition (ICD-10), and National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA).

The exclusion criteria for articles were as follows: (1) literature with duplicates, incomplete data, or unclear outcome effects, (2) literature with flaws in research design and poor quality, (3) reviews, letters, conferences, case reports, and meta-analyses.

Literature screening and data extraction

The quality of the included studies was independently assessed and cross-validated by two other researchers using NoteExpress. In cases of disagreement, a third researcher was consulted to reach a consensus. Uncertain data were defined by contacting the original authors. An Excel database was established to draft a research data information table according to the needs of the relevant studies, extracting research-related information such as authors, publication year, region, study methodology, basic characteristics of the study population, sample size, exposure factors, and outcome indicators.

Assessment of bias risk

The quality of the included studies was independently assessed and cross-checked by two researchers. The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Rating Scale (Newcastle-Ottawa, NOS) was used to assess the quality of the included studies (13). This scale assessed the quality of studies based on three aspects: selection of study groups, comparability of groups, and ascertainment of exposure and outcomes. Of a possible score of nine, four points were included in the selection of study groups, two points were included in the comparability of groups, and three points were included in the ascertainment of exposure and outcomes. Included studies with a score of seven or more were considered as researches with high-quality.

Statistical analyses

The meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.4. The effect size of each study outcome was described by the odds ratios (OR), hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Cochran’s Q test and chi-square (I2) test were used to assess the statistical heterogeneity between studies. The P value less than 0.05 and a value of I2 of 0% to 50% indicated statistical heterogeneity between studies, and a random effects model was selected. If there was no significant heterogeneity between study groups, a fixed effect model was chosen. Sensitivity analysis was also conducted to explore the sources of heterogeneity, and a funnel plot and Begg’s test were used to assess publication bias and the overall stability of the study. The P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Literature search

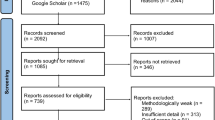

The preliminary search yielded 2028 pieces of related literature initially, and up to 2029 studies in total with an additional article obtained from other sources. After removing 317 duplicates, 1712 relevant articles were obtained. After screening the titles and abstracts, 1604 articles were excluded, resulting in 108 remained articles. After the full-text review, 86 articles were excluded, leaving a final inclusion of 22 articles (14–35). Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the selection process.

Characteristics of the included studies

A total of 22 studies were enrolled in this study including eight longitudinal cohort and 14 cross-sectional studies, with 4,246,608 participants. The 22 included studies had quality scores ranging from 6 to 8, indicating that they were having medium to high quality, as described in Table 1.

Different dimensions of poor periodontal health and cognitive impairment in older adults

Poor periodontal health was defined as an abnormality in at least one of four dimensions of periodontitis, tooth loss, occlusal support, or masticatory ability. Cognitive assessment tools and diagnostic criteria were used to screen for older adults with cognitive impairment. Among the 22 studies, six studies (16–20, 28) reported an association between periodontitis and cognitive impairment in older people, and the meta-analysis results showed that periodontitis had a negative impact on cognitive function in older adults (OR=1.45, 95% CI: 1.20–1.76, P<0.001). Seventeen studies (19–35) investigated the link between tooth loss and cognitive impairment in the older population, indicating a significantly increased risk of cognitive impairment in older adults with tooth loss (OR=1.80, 95% CI: 1.50–2.15, P<0.001). Two studies (19, 33) examined the association between occlusal support and cognitive impairment, demonstrating that older adults with poor occlusal support were more likely to experience cognitive impairment (OR=1.87, 95% CI: 1.29–2.70, P=0.001). Three studies (15, 23, 29) explored the association between masticatory ability and cognitive impairment in the older population, suggesting that older adults with weak masticatory ability faced a significantly increased risk of developing cognitive impairment (OR=1.39, 95% CI: 1.11–1.75, P=0.005). Taken together, the analyses suggested that periodontitis, tooth loss, occlusal support, and masticatory ability all contribute to an increased risk of cognitive impairment in older adults (Figure 2).

Forest plot for association between different dimensions of poor periodontal health and cognitive impairment in older adults

(A) Association between poor periodontal health and cognitive impairment. (B) Association between tooth loss and cognitive impairment. (C) Association between occlusal support and cognitive impairment. (D) Association between masticatory ability and cognitive impairment.

Association of different numbers of teeth lost with cognitive impairment

Thirteen studies (19–28) investigated the association between specific number of teeth lost and cognitive impairment. Based on the reported numbers of tooth loss in each study, a further stratified analysis of the association between tooth loss and cognitive impairment was conducted, and ultimately 10 studies were included and divided into four groups (7–17 teeth compared to 0–6 teeth, 9–28 teeth compared to 0–8 teeth, 19–28 teeth compared to 0–18 teeth, and 28 teeth compared to 0–27 teeth). Two studies (25, 27) reported an association between the number of teeth lost (7–17 vs. 0–6) and cognitive impairment, highlighting the missing 7–17 teeth as a risk factor for cognitive impairment (OR=1.64, 95% CI: 1.13–2.39, P=0.01); five studies (19–23) revealed an association between the number of teeth lost (9–28 vs. 0–8) and cognitive impairment, indicating that the missing 9–28 teeth posed a risk for cognitive impairment (OR=1.13, 95% CI: 1.06–1.20, P<0.001); two studies (24, 26) demonstrated a link between the number of teeth lost (19–28 vs. 0–18) and cognitive impairment, with the missing 19–28 teeth identified as a risk factor for cognitive impairment (OR=2.52, 95% CI: 1.32–4.80, P=0.005); three studies (20, 22, 28) reported an association between the number of teeth lost (28 vs. 0–27) and cognitive impairment, revealing that complete tooth loss significantly heightened the risk of cognitive impairment (OR=2.07, 95% CI: 1.54–2.77, P<0.001). All above results showed that older people in the low-dentition group have a greater risk of cognitive impairment compared to those in the high-dentition group (Figure 3).

Forest plots for association between different number of teeth lost and cognitive impairment in older adults

(A) Association between tooth loss (7–17 teeth compared to 0–6 teeth) and cognitive impairment. (B) Association between tooth loss (9–28 teeth compared to 0–8 teeth) and cognitive impairment. (C) Association between tooth loss (19–28 teeth compared to 0–18 teeth) and cognitive impairment. (D) Association between tooth loss (28 teeth compared to 0–27 teeth) and cognitive impairment

Association between tooth loss and mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease and all-cause dementia

Thirteen studies (19, 20, 23, 24, 25, 27–34) reported that the tooth loss was considered a risk factor for MCI (OR=1.66, 95% CI: 1.43–1.91, P<0.001). Two studies (21, 22) indicated that tooth loss increased the risk of developing AD (OR=3.89, 95% CI: 0.68–22.31, P=0.13). Additionally, two studies (26, 35) found tooth loss to be a risk factor for all-cause dementia (OR=1.35, 95% CI: 1.11–1.65, P=0.003). The results suggested that tooth loss in older adults significantly elevates the risk of MCI and all-cause dementia, with a positive but statistically insignificant correlation between tooth loss and AD (Figure 4).

Forest plots for the association between tooth loss and mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease or all-cause dementia in older adults

(A) Association between tooth loss and mild cognitive impairment. (B) Association between tooth loss and Alzheimer’s disease. (C) Association between tooth loss and all-cause dementia.

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

Sensitivity analysis was performed with STATA 14.0 to explore the overall impact of each study (Figure 5A). Excluding in turn any of the studies for merging, the results did not change significantly, indicating the stability of the meta-analysis findings. A funnel plot suggested no small-scale effect on the correlation between periodontal health and cognitive impairment in the older population (Figure 5B). Since Egger’s test showed publication bias in the model (t=7.45, P<0.01), prompting the use of the trim and fill method for sensitivity analysis. Nine hypothetical unpublished studies were estimated by STATA 14.0. After incorporating the hypothetical studies in the adjusted model, the pooled analysis remained significant (Q=68.80, P<0.01) (Figure 5C, Figure 5D).

Discussion

A meta-analysis of 22 recent publications showed a significant association between cognitive impairment and poor periodontal health in the older population. Periodontitis, tooth loss, and declines in occlusal support and masticatory ability all contributed to an increased risk of cognitive impairment in older adults after adjusting for confounders such as age and sex. In term to tooth loss, the more missing teeth, the higher risk of developing cognitive impairment in older adults, with edentulous older individuals particularly having a specially increased risk of cognitive impairment. Although there was a certain degree of increased risk of AD, no significant difference was observed between tooth loss and the risk of developing AD in older adults. Our research emphasizes the importance of enhancing periodontal health management and delivering high-quality oral health care services to older adults on preventing cognitive impairment.

The issue of periodontal health and cognitive impairment in older adults has become a focus of attention in the current aging society. Bumb (16) and Nilsson (18) both conducted longitudinal cohort studies on the relationship between periodontitis and cognitive impairment. The conclusions of both studies have shown that older individuals who developed periodontitis had a significantly increased risk of cognitive impairment 5 to 6 years later. Furthermore, Hatta (19) conducted a 3-year follow-up study on the relationship between occlusal support and cognitive impairment, finding that older individuals who experienced cognitive impairment within 3 years (a decline of ≥ 3 points in MoCA scores) had poorer bite support. This study confirmed that occlusal support is an important indicator of the risk of cognitive decline related to periodontal health. However, the results regarding the association between tooth loss and cognitive impairment in the older population are inconsistent (23, 24, 27, 30, 36). Most studies (23, 24, 27) have shown that tooth loss increases the risk of cognitive impairment in older adults. One of the follow-up studies by Saito demonstrated that having multiple missing teeth (only 0–9 remaining) significantly increases the risk of developing cognitive impairment within four years (24). In contrast, after adjusting for confounding factors such as age, sex, and education level, Shin (30) and Wu (36) found no association between tooth loss and cognitive impairment in older adults. Our present study explored the correlation not only between periodontitis, but also tooth loss, occlusal support, and masticatory ability with cognitive impairment. We found that the increased number of missing teeth in older adults increased risk of MCI and all-cause dementia and a certain degree of increased risk in AD, although the association between tooth loss and AD was not significant. Specifically, when older adults had fewer than 10 remaining teeth, the risk of cognitive impairment significantly increased. The risk of cognitive impairment in older adults without any remaining teeth was at least twice as high as that in those with one or more teeth. These findings provide additional points of focus for follow-up preventive measures against cognitive impairment from the perspective of oral health care services.

The correlation between periodontal health and cognitive impairment might involve in multiple mechanisms. First, oral pathogenic microorganisms and their toxic substances that caused periodontitis can directly affect the brain through the trigeminal/olfactory/facial nervous system and the circulatory system, or indirectly induce systemic inflammation by migrating to the intestines and entering the circulatory system, or by disrupting the balance of intestinal microbiota through the enteric nervous system or indirectly mediating systemic inflammation, leading to neuroinflammation mediated by neuroglial cells (37, 38). Second, periodontitis can contribute to the development of cognitive impairment in older adults by increasing the occurrence of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Previous studies have shown that diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and other conditions are risk factors for cognitive impairment in older adults (4, 39–42). Third, as individuals age, physiological degeneration of tissues such as the gums and alveolar bone occurs, leading to tooth loss. Oral diseases such as periodontitis and dental caries can also cause tooth loss by damaging periodontal tissues and teeth. Research has shown a dose-response relationship between the number of missing teeth and the risk of cognitive decline, significantly strengthening the connection between tooth loss and cognitive impairment (43). Our study revealed that the number of missing teeth increased the risk of cognitive impairment in older adults, with a significantly higher risk for edentulous individuals than for those with partially missing teeth. This provides some clues for understanding the dose-response relationship. Severe tooth loss is related to chronic disease development (such as periodontitis), and long-term chronic development may lead to complete tooth loss, increasing the likelihood of cognitive impairment. Currently, there is a lack of research on the details and evidence related to the causes and duration of tooth loss in the older population. Additionally, tooth loss in older adults can severely impact occlusal support (33, 44) and chewing, which leading the deficiency of important nutritional composition that important for maintaining cognitive function, such as vitamins B and C (45–47). Research has shown that chewing can have an impact on memory-related brain regions, such as the hippocampus (48).

This study has several limitations. First, the current study explored the unidirectional impact of poor periodontal health on cognition in older adults. Research on the reverse effect of cognitive impairment on the development of periodontal health is limited. Furthermore, there is a notable lack of research on whether deteriorating periodontal health worsens with the progression of dementia. Additional longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the interaction between periodontal health and cognition. Second, only observational studies were included in the research, and further expansion of the study types is needed. Future experimental studies could confirm the association between periodontal health and cognitive impairment and identify interventions that effectively maintain periodontal health and delay the onset of cognitive impairment in older adults.

Conclusion

Based on the available evidence, we conducted a meta-analysis of the correlation between four dimensions of oral health (periodontitis, tooth loss, occlusal support and masticatory ability) and the risk of cognitive impairment in older adults. Our findings indicated that periodontitis, tooth loss, occlusal support and masticatory ability all contribute to an increased risk of cognitive impairment in older adults. Further analysis of the correlation between tooth loss and cognitive impairment revealed that the greater the number of missing teeth in older adults, the higher the risk of developing cognitive impairment, with edentulous older individuals particularly at an increased risk of cognitive impairment. However, there was no significant association between tooth loss and the risk of developing AD in older adults. Tooth loss was positively associated with the risk of developing all-cause dementia and mild cognitive impairment among older adults over the age of 60, and additional studies are needed to support this conclusion. This study emphasizes that maintaining good periodontal health is crucial for preventing cognitive impairment of older individuals.

References

World Health Organization. Ageing and health. 2022. https://www.who.int/zh/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health. Accessed1 October 2022

United Nations. World Social Report 2023: Leaving No One Behind In An Ageing World. 2023. https://news.un.org/zh/story/2023/01/1114127. Accessed 12 January 2023

Expert Consensus Group on the Prevention and Treatment of Cognitive Impairment in China. Expert Consensus on the Prevention and Treatment of Cognitive Impairment in China. Chin J Intern Med. 2006;45(2):171–173. doi:https://doi.org/10.3760/j.issn:0578-1426.2006.02.029

Jia L, Du Y, Chu L, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and management of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in adults aged 60 years or older in China: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(12):e661–e671. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30185-7.

Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):413–446. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6

Chinese Stomatological Association, Yu GY, Wang QT, et al. Consensus of Chinese stomatological multidisciplinary experts on maintaining periodontal Health (First Edition). Chin J Stomatol. 2021;56(2):9. doi:https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112144-20210112-00013

Kinane DF, Stathopoulou PG, Papapanou PN. Periodontol diseases. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17038. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.38

Lang NP, Bartold PM. Periodontol health. J Periodontol. 2018;89 Suppl 1:S9–S16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.16-0517

Raphael C. Oral Health and Aging. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(S1):S44–S45. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.303835

Northridge ME, Kumar A, Kaur R. Disparities in Access to Oral Health Care. Annu Rev Public Health. 2020;41:513–535. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094318

Wang X. The Fourth National Oral Health Epidemiological Survey Report. 2018. Beijing, People’s Medical Publishing House.

Peres MA, Macpherson LMD, Weyant RJ, et al. Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. Lancet. 2019;394(10194):249–260. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31146-8

Wells G. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Non-Randomised Studies in Meta-Analyses[C]//Symposium on Systematic Reviews: Beyond the Basics. 2014. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/bioe.2002.0137

Iwasaki M, Yoshihara A, Kimura Y, et al. Longitudinal relationship of severe periodontitis with cognitive decline in older Japanese. J Periodontol Res. 2016;51(5):681–688.doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jre.12348

Suzuki H, Furuya J, Hidaka R, et al. Patients with mild cognitive impairment diagnosed at dementia clinic display decreased maximum occlusal force: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21(1):665.doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-021-02027-8

Bumb, S. S., Govindan, C. C., Kadtane, S. S., et al. Association between cognitive decline and oral health status in the aging population: A 5-year observational study. GeroPsych: The Journal of Gerontopsychology and Geriatric Psychiatry, 2022, 35(4), 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1024/1662-9647/a000271

Marruganti C, Baima G, Aimetti M, et al. Periodontitis and low cognitive performance: A population-based study. J Clin Periodontol. 2023;50(4):418–429. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.13779

Nilsson H, Berglund JS, Renvert S. Periodontitis, tooth loss and cognitive functions among older adults. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22(5):2103–2109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-017-2307-8

Hatta K, Ikebe K, Gondo Y, et al. Influence of lack of posterior occlusal support on cognitive decline among 80-year-old Japanese people in a 3-year prospective study. GeriatrGerontol Int. 2018;18(10):1439–1446.doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13508

Nilsson H, Berglund J, Renvert S. Tooth loss and cognitive functions among older adults. Acta Odontol Scand. 2014;72(8):639–644.doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/00016357.2014.882983

Lopez-Jornet P, Zamora Lavella C, Pons-Fuster Lopez E, Tvarijonaviciute A. Oral Health Status in Older People with Dementia: A Case-Control Study. J Clin Med. 2021;10(3):477.doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10030477

Tsuneishi M, Yamamoto T, Yamaguchi T, et al. Association between number of teeth and Alzheimer’s disease using the National Database of Health Insurance Claims and Specific Health Checkups of Japan. PLoS One. 2021;16(4):e0251056.doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251056

Takehara S, Wright FAC, Waite LM, et al. Oral health and cognitive status in the Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project: A cross-sectional study in community-dwelling older Australian men. Gerodontology. 2020;37(4):353–360.doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ger.12469

Saito S, Ohi T, Murakami T, Komiyama T, et al. Association between tooth loss and cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older Japanese adults: a 4-year prospective cohort study from the Ohasama study. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18(1):142.doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-018-0602-7

Saito Y, Sugawara N, Yasui-Furukori N, Takahashi I, Nakaji S, Kimura H. Cognitive function and number of teeth in a community-dwelling population in Japan. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2013;12(1):20.doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-859X-12-20

Stein PS, Desrosiers M, Donegan SJ, et al. Tooth loss, dementia and neuropathology in the Nun study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138(10):1314–1382. doi:https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0046

Okamoto N, Morikawa M, Okamoto K, et al. Relationship of tooth loss to mild memory impairment and cognitive impairment: findings from the Fujiwarakyo study. Behav Brain Funct. 2010;6:77.doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-9081-6-77

Iwasaki M, Kimura Y, Yoshihara A, et al. Oral health status in relation to cognitive function among older Japanese. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2015;1(1):3–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cre2.2

Lexomboon D, Trulsson M, Wårdh I, Parker MG. Chewing ability and tooth loss: association with cognitive impairment in an elderly population study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(10):1951–1956.doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04154.x

Shin MS, Shin YJ, Karna S, Kim HD. Rehabilitation of lost teeth related to maintenance of cognitive function. Oral Dis. 2019;25(1):290–299.doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.12960

Turnbull N, Cherdsakul P, Chanaboon S, et al. Tooth Loss, Cognitive Impairment and Fall Risk: A Cross-Sectional Study of Older Adults in Rural Thailand. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(23):16015.doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316015

Xu S, Huang X, Gong Y, Sun J. Association between tooth loss rate and risk of mild cognitive impairment in older adults: a population-based longitudinal study. Aging (Albany NY). 2021;13(17):21599–21609. doi:https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.203504

Jiang Z, Liu X, Lü Y. Unhealthy oral status contributes to the older patients with cognitive frailty: an analysis based on a 5-year database. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):980.doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03673-5

Luo J, Wu B, Zhao Q, et al. Association between tooth loss and cognitive function among 3063 Chinese older adults: a community-based study. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0120986.doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0120986

Yoo JJ, Yoon JH, Kang MJ, et al. The effect of missing teeth on dementia in older people: a nationwide population-based cohort study in South Korea. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19(1):61.doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-019-0750-4

Wu B, Fillenbaum GG, Plassman BL, Guo L. Association Between Oral Health and Cognitive Status: A Systematic Review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(4):739–751. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14036

Arimatsu K, Yamada H, Miyazawa H, et al. Oral pathobiont induces systemic inflammation and metabolic changes associated with alteration of gut microbiota. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4828. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04828

Lam GA, Albarrak H, McColl CJ, et al. The Oral-Gut Axis: Periodontol Diseases and Gastrointestinal Disorders. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29(7):1153–1164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izac241

Baumgart M, Snyder HM, Carrillo MC, Fazio S, Kim H, Johns H. Summary of the evidence on modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia: A population-based perspective. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(6):718–726. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.016

Bao H, Liu Y, Zhang M, et al. Increased β-site APP cleaving enzyme 1-mediated insulin receptor cleavage in type 2 diabetes mellitus with cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(7):1097–1108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12276

Chinese Society of Geriatrics, Chinese Society of Geriatrics Hypertension Branch, Chinese Society of Geriatrics Cognitive Impairment Branch, et al. Chinese expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension and cognitive impairment in the elderly(2021). Chin. J. Clin. Healthcare. 2021;24(2):145–159.doi:https://doi.org/10.11915/j.issn.1671-5403.2021.04.052

Ungvari Z, Toth P, Tarantini S, et al. Hypertension-induced cognitive impairment: from pathophysiology to public health. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2021;17(10):639–654. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-021-00430-6

Qi X, Zhu Z, Plassman BL, Wu B. Dose-Response Meta-Analysis on Tooth Loss With the Risk of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(10):2039–2045. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2021.05.009

Yoo JJ, Yoon JH, Kang MJ, Kim M, Oh N. The effect of missing teeth on dementia in older people: a nationwide population-based cohort study in South Korea. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19(1):61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-019-0750-4

Gil Martínez V, Avedillo Salas A, Santander Ballestín S. Vitamin Supplementation and Dementia: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2022;14(5):1033.doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14051033

Suh SW, Kim HS, Han JH, et al. Efficacy of Vitamins on Cognitive Function of Non-Demented People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):1168. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041168

Forbes SC, Holroyd-Leduc JM, Poulin MJ, Hogan DB. Effect of Nutrients, Dietary Supplements and Vitamins on Cognition: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Can Geriatr J. 2015;18(4):231–245. doi:https://doi.org/10.5770/cgj.18.189

Huang DZ, Zhang Q, Jiang H. Research progress on correlation between mastication and memory. J Prosthodont. 2019;20(06):357–362.doi:https://doi.org/10.19748/j.cn.kqxf.1009-3761.2019.06.008

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the authors of the included trails and their participants.

Funding

Funding: This work was supported financially by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (72174159).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate: Not applicable.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, YD., Li, CL., Hu, CL. et al. Meta Analysis of the Correlation between Periodontal Health and Cognitive Impairment in the Older Population. J Prev Alzheimers Dis (2024). https://doi.org/10.14283/jpad.2024.87

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14283/jpad.2024.87